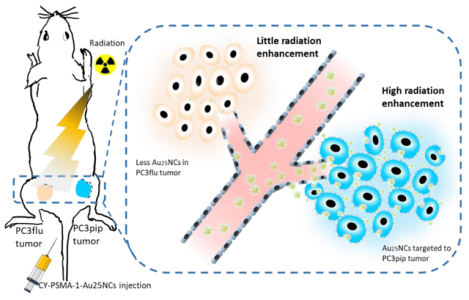

Graphical Abstract

Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA) targeted radiosensitizers are developed for prostate cancer radiotherapy based on gold nanoclusters and a high-affinnity targeting peptide, PSMA-1 (CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs). The CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs can achieve rapidly and selectively uptake by prostate cancer in vitro and in vivo, efficient renal clearance, and high prostate cancer radiotherapy enhancement.

Keywords: gold nanocluster, radiosensitization, targeted radiotherapy, PSMA, prostate cancer

For over a hundred years, X-rays have been a main component of the radiotherapeutic approaches to treat cancer. Yet, to date, no radiosensitizer has been developed to selectively target prostate cancer. Gold has excellent X-ray absorptivity and has been used as a radiotherapy enhancing material. In this work, ultrasmall Au25 nanoclusters (NCs) have been developed for selective prostate cancer targeting, radiotherapy enhancement, and rapid clearance from the body. Targeted-Au25 NCs are rapidly and selectively taken up by prostate cancer in vitro and in vivo and also have fast renal clearance. When combined with X-ray irradiation of the targeted cancer tissues, radiotherapy was significantly enhanced. The selective targeting and rapid clearance of the nanoclusters may allow reductions in radiation dose, decreasing exposure to healthy tissue, and making them highly attractive for clinical translation.

Prostate cancer is the most diagnosed cancer among men in the United States.[1] For treatment of prostate cancer, radical prostatectomy still remains the most direct and effective approach. However, when the cancer has extended beyond the prostate, surgery may be unable to remove all the malignant nodules, resulting in a high recurrence rate of the cancer.[2] In this case, radiation therapy is often necessary to reduce surgery-related morbidities. More than half of the patients receive radiation in the form of electrons, protons or photons (gamma- or X-rays) during their battle against cancers.[3, 4] However, in the practice of radiation treatment, normal tissue is also exposed and potential radiotoxicity is, thus, unavoidable. Improvement has been made for radiotherapy, such as using megavolt (6–25 MV) X-rays to avoid skin damage and tomotherapy and intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) to better focus the radiation to the tumor.[5] However, radiotherapy alone is less likely to succeed when the tumor cells are radioresistant (e.g. hypoxic), under-irradiated, or outside the targeted region.[6]

Radiosensitizers increase the effects of radiation dose in the cancer region on the cellular level and enhance the outcome of radiation therapy, even for radioresistant resistant cells, while simultaneously lowering off-target radiation doses. Materials with a high atomic numbers (Z) (e.g. iodine, gadolinium, and gold), exhibit high X-ray absorption coefficients.[4, 6] Upon X-ray radiation, such radiosensitizers can generate secondary effects in the form of scattered photons, electrons, electron-positron pairs, or fluorescence. The secondary electrons can compromise and kill the cancer cells.[3, 7, 8] The radiation enhancement is especially outstanding for gold (Z=79). Gold has a much higher absorbance of radiation compared to normal tissue with up to a 100-fold enhancement in the keV energy range.[9].

While, gold nanoparticles have attracted great attention as radiosensitizers,[8, 10] there are two common issues that hamper the use of gold nanoparticles as radiosensitizers: 1) The first issue is non-specific accumulation of untargeted gold nanoparticles into non-cancerous tissues. An undesirable deposition of gold nanoparticles into healthy tissue can lead to significant damage to the healthy tissue due to elemental toxicity and spurious X-ray administration; 2) The second issue related to gold nanoparticles in therapeutic applications is their route of elimination from the body. Gold nanoparticles are very stable in vivo, and due to their typical sizes (8–500 nm), they tend to clear the body much slower than small molecules and are accumulated in the liver and spleen, which may induce changes in gene expression and liver necrosis.[6] Although the data is not conclusive, apparent gold nanoparticle toxicities, which include death, are related to particle size (8–37 nm being the most toxic sizes), particle charge, and particle coatings, and are likely due to activation of immunoresponse in animals.[11]

In recent years, there have been numerous studies to investigate the potential of gold nanoparticles as radiosensitizers.[5] Glutathione (GSH) stabilized gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) have been extensively studied and applied in biomedical imaging and theranostics.[12] GSH-coated NCs have a long circulation lifetime in vivo and high accumulation in tumors due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect.[13] Thus, they have been utilized as untargeted radiosensitizers,[7] but, off target accumulation still significantly limits this approach for radiotherapy.

There have been a few studies exploring in-vivo radiotherapy with targeted gold nanoparticles. Though, targeting ligands, such as folic acid and RGD peptides, conjugated to gold nanoparticles generally improve the accumulation of gold at tumors,[14] they commonly lack specificity. For instance, folate-targeted gold nanoparticles are highly effective radiosensitizers for tumors formed from Hela cells, but for tumor from MCF-7 cells, the effect is marginal.[15] Furthermore, there is evidence that targeting ligands on AuNP can increase or decrease toxicity.[11] Therefore, to identify a suitable cancer-selective biomarker and develop a highly-selective targeted gold nanoparticle, which will be rapidly cleared from the body, is a challenge for designing gold radiosensitizers.

Prostate specific membrane antigen, PSMA, is an excellent biomarker for AuNC targeting. It is a type II membrane protein, which is highly expressed in most prostate cancers.[2] It is not secreted and is membrane bound, making it an attractive extracellular target for therapeutic probes for prostate cancer.[16] In clinical studies, Lutetium 177 (Lu) labelled PSMA peptides have already proved to be effective in targeted radionuclide therapy of prostate cancer.[17] Recently, we have developed a high-affinity PSMA targeting ligand (PSMA-1) and demonstrated its use in prostate cancer imaging and photodynamic therapy.[2, 18] Here the PSMA-1 ligand is further modified for in-situ synthesis of PSMA-1-targeted Au25 nanoclusters (CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs), providing a high-affinity and highly effective radiosensitizer for prostate cancer that is also small enough to be excreted by the kidneys within hours. The resulting CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs effectively enhanced the targeted radiotherapy in vivo and fast renal elimination may simultaneously reduce the sensitizer-induced off-target and elemental toxicity (Figure. 1).

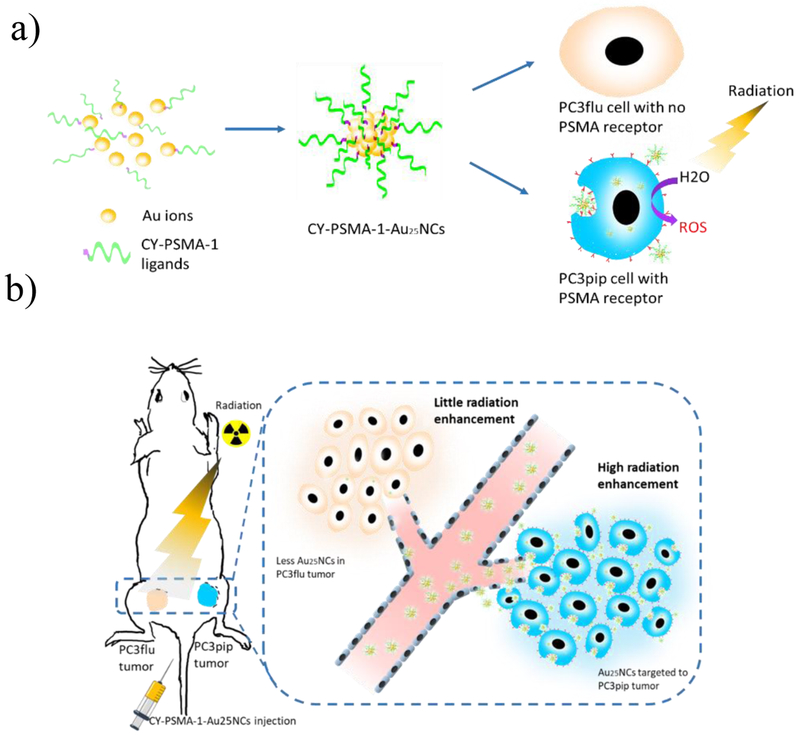

Figure 1.

CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs for targeted radiotherapy of prostate cancer. a) Schematic of synthesis of CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs radiosensitizer, with high affinity to the PSMA-expressing PC3pip cells. b) Illustration of PC3pip and PC3flu tumor targeting and radiation therapy with CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs. PSMA-expressing PC3pip cells and PSMA-negative PC3flu cells are implanted on the flanks of the same mouse. Intravenous injection of nanoclusters results in higher targeting levels to the PC3pip tumor than to the PC3flu tumor and, thus, improved radiation therapy.

To address the challenges for developing a highly selective gold-based radiation sensitizer, we have utilized the highly-selective PSMA ligand for prostate cancer and combined it with AuNCs of 1.5 nm in diameter, which is well below the threshold for renal clearance (~5.5 nm)[19] and therefore reduces unintended and nonspecific organ uptake by the liver and spleen[20, 21] as well as any potential gold cluster induced organ toxicity.

Previously we have developed a high-affinity ligand, PSMA-1, for the PSMA receptor, which is over-expressed on most prostate cancers. Using optical imaging fluorophores we have demonstrated its selectivity for the PSMA receptor and its biodistribution in mouse models of prostate cancer. To generate PSMA-targeted Au25NCs, we first re-synthesized the PSMA-1 to include two additional amino acids (Figure. S1 and S2). The new ligand, CY-PSMA-1, retained high affinity for the PSMA expressing cells and contained additional Cys and Tyr residues to enable reduction and capping of the nanoclusters (NCs), which was the foundation for in-situ Au25NC formation (Figure. S3–5).[22] The ligand was combined at pH 12 with Au3+ ions resulting in the formation of Au25NCs. The nanoclusters formed were examined with TEM and showed that the PSMA-targeted Au25NCs have a narrow size distribution of 1.5 (±0.5) nm (Figure. 2a), and a hydrodynamic diameter of 3.0 (±0.7) nm (Figure. 2b). The CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs exhibited an excitation peak at 490 nm and emission peak at 700 nm (Figure. 2c). Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) confirmed the presence of CY-PSMA-1 and S-Au bonding (Figure. S6). Further characterization using MALDI-TOF MS confirmed AuNCs consisting of 25 Au atoms, which are known to be highly stable (Figure. 2d).[23] We next tested if the CY-PSMA-1-Au25NC had good stability under physiological conditions. After incubation with 10% FBS solution at 37℃ for 30 min, the complex was analyzed using gel electrophoresis showing that there was no detectable serum adsorption to the Au25NCs (Figure. S7).

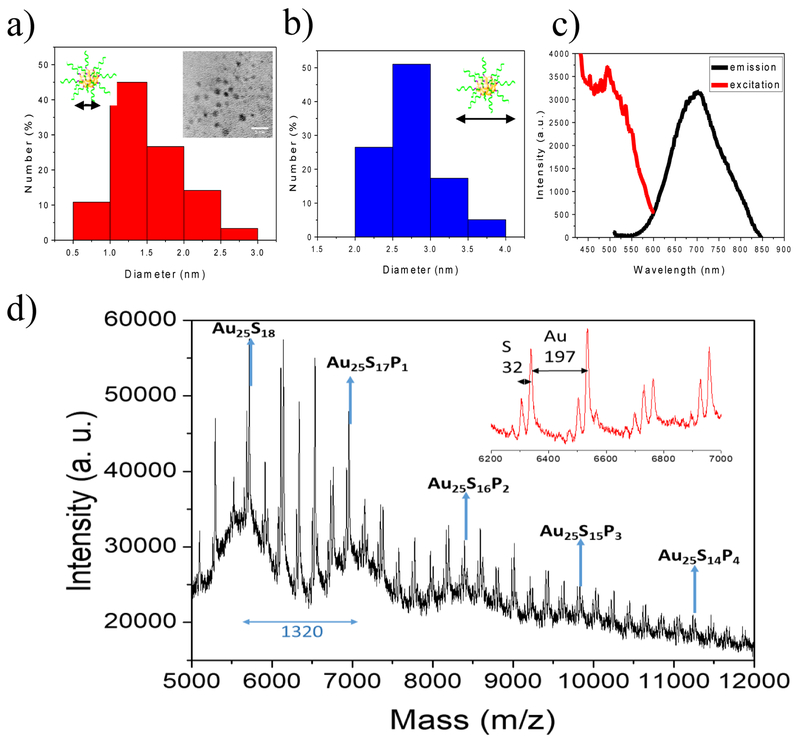

Figure 2.

a) Distribution of core diameters of CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs. Inset shows a TEM image of Au25NCs (scale bar 5 nm). b) Distribution of the hydrodynamic diameters of CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs. c) Excitation and emission spectra of nanoclusters showing peaks at 490 nm (ex) and 700 nm (em). d) MALDI-MS spectra for CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs. A series of intense peaks between 5–12k m/z fit the formula Au25S(18-m)Pm (P=CY-PSMA-1) (m= 0–18), and the difference between adjacent intense peaks is 1320, which matches the molecular weight of CY-PSMA-1 with one thiol group missing. The inset is an expanded view of peak details in the range 6.2k-7k. Space between the minor peaks is 197 m/z and 32 m/z, which corresponds to the loss of Au and S atoms, respectively. Matrix, CHCA, linear model.

Our first step in evaluating the utility of these targeted-NC was to measure uptake in vitro. PSMA receptor positive, PC3pip, or PSMA-receptor negative, PC3flu, cells were incubated with CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs. Confocal fluorescence imaging of the cells showed that the PC3pip cells bind and take up the nanoclusters more avidly than the receptor-negative PC3flu cells (Figure. 3a). Interestingly, many nanoclusters are co-localized with nuclei. To further determine if the NCs were within the nucleus or just near it, we performed 3D confocal microscopic scanning and reconstructed 3D images that showed most of the nanoclusters were in the perinuclear space (Figure S8). This outcome is advantageous in radiotherapy since most radiation-induced damage to tumor cells is via DNA strand breaks. ICP-MS measurements of the gold content in each set of cells showed that PC3pip cells had almost a 2-fold higher Au content than the PC3flu cells (Figure. 3b), suggesting that targeting the Au25NC to PSMA receptor doubles uptake. We next measured binding of the targeted-NCs to cells using a competition binding assay. PSMA-expressing LNcap cells were incubated with CY-PSMA-1, CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs and the parent ligand ZJ24 at various concentrations in the presence of 12 nM 3H-labelled ZJ24 ligand. The cell uptake associated radioactivity was measured via a scintillation counter. Compared to ZJ24 (IC50=8.31 nM) and CY-PSMA-1 (IC50=1.69 nM) ligands, the PSMA-targeted Au25NCs exhibited a remarkably lower IC50 value (IC50=0.09 nM), indicating an excellent targeting affinity likely due to avidity effects (Figure. 3c).

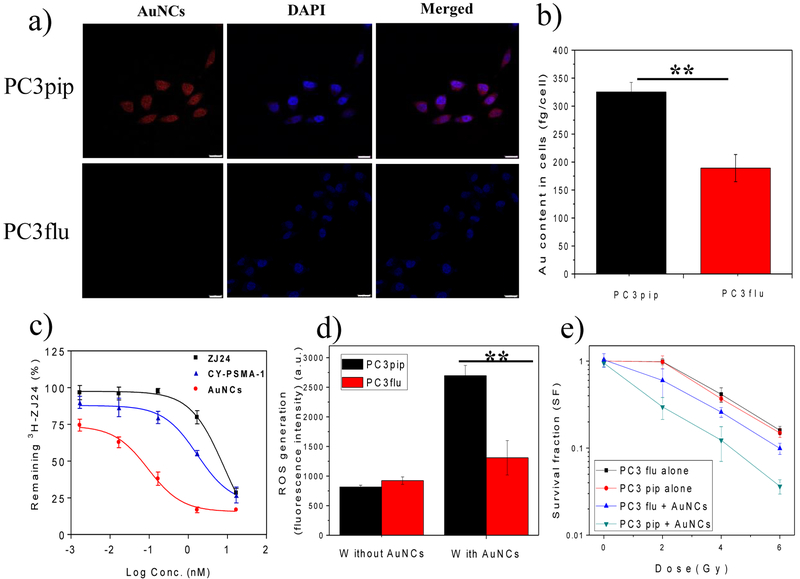

Figure 3.

a) Confocal images of the uptake of CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs by PC3pip and PC3flu cells after 24 h incubation at 30 μg Au/mL. Au25NCs show a red fluorescence and DAPI is used for nuclear staining (scale bar 25 μm). b) ICP-MS measurement of Au content in cells, showing significantly higher Au content in PC3pip cells than in PC3flu cells. c) Competition binding curves for parent ZJ24, CY-PSMA-1 ligands, and CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs. d) In vitro ROS generation by a DCFDA assay. Non-fluorescent DCFDA was converted into fluorescent DCF− by intracellular ROS upon 6 Gy radiation. e) Survival curves of PC3pip and PC3flu cells with and without addition of CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs under radiation at doses of 0, 2, 4, and 6 Gy. Data are presented as mean ± SD. n = 3; two-tailed t-test: **P < 0.05.

Our next in vitro study was to determine if the targeted-NCs could serve to improve radiotherapy. Though the mechanism of radiosensitization by gold is still not fully understood, some studies indicated that reactive oxygen species (ROS) would be generated by electron ejection from gold upon irradiation.[24] We first tested to see if irradiated gold nanoclusters would generate ROS using a DCFDA assay. DCFDA is a non-fluorescent molecule that coverts to fluorescent DCF− upon exposure to ROS. PC3pip and PC3flu cells were incubated with targeted-Au25NCs for 24 hours and then irradiated (6 Gy), Figure 3d. PC3pip cells incubated with nanoclusters generated much more DCFDA conversion and fluorescence of DCF− after irradiation, 3.3 times more compared to PC3pip cells without targeted-AuNCs. In contrast, PC3flu cells produced only 1.4 times enhancement compared to controls, indicating successful targeting and ROS production. This was also confirmed in the fluorescence images that PC3pip cells showed green fluorescence after irradiation while the PC3flu cells did not (Figure S9). To see if ROS generation converted to increase cellular toxicity, in vitro radiation sensitization was measured using a colony survival assay. According to the cell survival fraction curves (Figure. 3e), radiation sensitivity was enhanced for PC3pip cells incubated with PSMA-targeted Au25NCs compared to PC3flu or control cells not incubated with any Au25NCs. By fitting the survival curves to a multitarget single-hit model,[25] the sensitization enhancement ratios (SER, defined as the ratio of survival fractions without and with NPs at a survival lever of 50%) of PSMA-targeted Au25NCs for PC3pip and PC3flu cells were determined to be 2.1 and 1.4, respectively. This suggests that actively targeting of Au25NCs to PC3pip cells can significantly enhance the radiation sensitivity.

Next, we performed in vivo experiments to evaluate the tumor targeting ability and clearance of CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs. The ultrasmall size of the targeted-Au25NCs is especially attractive for in vivo tumor theranostics already benefiting from the passive tumor targeting ability and high renal clearance rate for such small clusters.[26] We established a prostate tumor model,[19] where both PSMA-positive and PSMA-negative tumors were implanted on the flanks of the same mouse and then used X-ray computed tomography (CT) to monitor specific Au accumulation within the tumors and in the bladder. Following a pre-injection scan, CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs were injected into the tail vein of the animals and CT scans were carried out at 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 6 h, and 24 h post-injection. Reconstruction of the 3D X-ray CT images showed increased CY-PSMA-1-Au25NC in the PSMA-overexpressing PC3pip tumors as early as 1 hour after injection, peaking at 4 hours after injection, and clearance of the nanoclusters by 24 hours. In contrast, the PC3flu tumor showed almost no signal enhancement even at 4 hours post injection (Figure 4a, indicated by green circles). The CT signal is a direct reflection of the local Au atom concentration (Figure S11).[7] The corresponding CT values at tumor sites were plotted in Figure 4b showing that in PC3pip tumors the Au25NC content reached 374 Hounsfield unit (HU) at 4 h, compared to 195 HU monitored at the PC3flu tumor, the only difference being the active targeting of targeted-Au25NCs via the PSMA antigen. Importantly, the bladder could be clearly identified in the 3D CT images (indicated by red circles) 30 min post injection with bladder accumulation peaking at 4 h after injection (Figure 4c). This suggests that fast renal clearance eliminates the CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs from the animals within hours. According to the circulation of CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs in blood after injection, the gold content in blood dropped dramatically in the first 3 hours, and then leveled off. The fast clearance of NCs likely benefited from the NC’s small size (Figure S10).

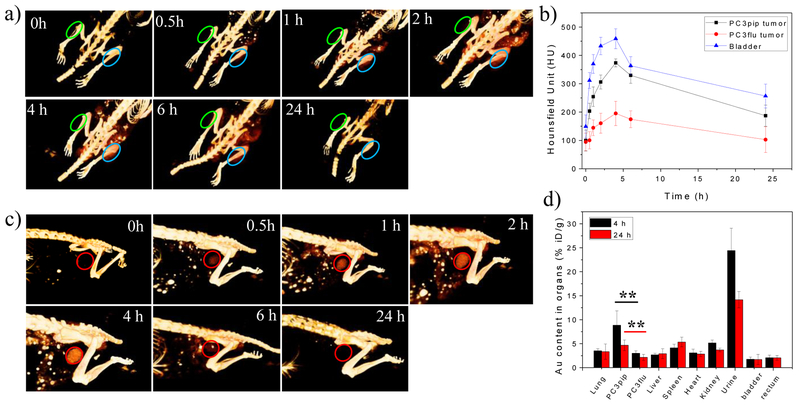

Figure 4.

a) In vivo 3D CT images of the PC3pip (right, blue) and PC3flu (left, green) tumor-bearing mice (indicated by blue and green ovals) before and at 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 6 h, and 24 h after intravenous injection of CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs (30 μg Au/g mouse); b) The CT signals at the tumor regions and bladder at each time point after CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs injection; c) In vivo 3D CT images of the bladders of mice (indicated by red circles) at each time point; d) Biodistribution of CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs in the main organs/urine at 4 h and 24 h post injection, as determined by ICP-MS (data are presented as mean ± SD. n = 3; two-tailed t-test: **P < 0.05).

To further understand the in vivo behavior of CY-PSMA-1-Au25NC, we analyzed Au biodistribution at 4 h and 24 h post injection using ICP-MS. As shown in Figure. 4d, the Au amount in PC3pip tumor was 2.9 and 2.2 times of that in the PC3flu tumor at 4 h and 24 h, respectively. This shows that targeting the PSMA receptor overexpressed on prostate cancer cells (PC3pip) provides greater accumulation of the targeted NCs than would occur by passive accumulation through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect.[19] Due to the fast clearance of the NCs, the untargeted AuNCs have a low accumulation in PSMA-lacking tumors with 2 % of injected dose (ID/g)[27] in contrast to the targeted Au25NCs that showed a high accumulation in PC3pip tumors with 8.9 % ID/g at 4 h post injection. This is greater than that achieved for RGD-targeted nanoclusters, which reached 6.4 %ID/g in 4T1 tumors after 4 h.[28] Moreover, the Au content in the liver is less than 3 %ID/g, which is much lower (about 1/5) compared to a study by Tsvirkun et al. using 10 nm, 30 nm, and 100 nm gold nanoparticles.[29] The Au content in bladder tissue and rectum is around 2%ID/g, which is even lower than the other main organs such as lung and heart. This may be due to less blood vessels in bladder and rectum. There is also no significant difference between 4h and 24 h. The low Au content in bladder tissue and rectum is beneficial in prostate cancer radiotherapy, reducing risk of accidental radiation. Au in urine can be mitigated by using ultra focused radiation on the tumor. However, in clinical radiotherapy the patient always gets an unavoidable bladder irradiation dose for typically used techniques of IMRT and arc therapy. Further work on investigating bladder toxicity and its minimization should be performed for the NCs, which may be potentially used for prostate cancer radiotherapy.

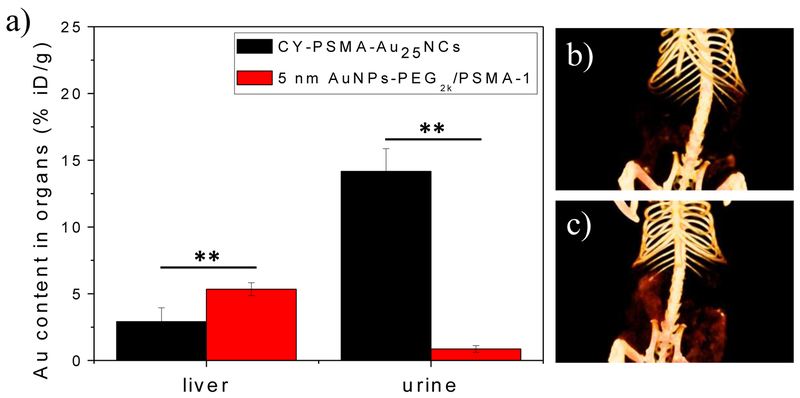

To determine the critical size effect on clearance, we also synthesized PSMA-targeted AuNPs, which had a core size of 5 nm and hydrodynamic size of 14 nm (Figure. S12). Injected at the same dose for gold, the PSMA-targeted AuNPs had about 2 times more Au accumulation in liver compared to Au25NCs and only 0.9 %ID/g in urine at 24 h post injection (Figure. 5a), indicating the AuNPs were unable to be cleared via urine. CT images of the digestive systems of mice at 24 h post injection also confirmed less accumulation of CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs in the gut than the 5 nm PSMA-targeted AuNPs (Figure. 5b, c). Presumably, since the CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs are smaller than the glomerular filtration cutoff, they escape capture by the reticuloendothelial system (RES)[20] and are excreted via the urinary system, limiting potential toxicity to the RES organs.[21] PSMA-targeted AuNPs with a size bigger than the renal-clearance threshold are slower or unable to be excreted from the kidney and will be cleared via the RES and digestion systems. The biodistribution results were consistent with the CT images, confirming that PSMA-targeted Au25NCs can be targeted to the PSMA-receptors expressed in tumors and also preferentially undergo renal clearance.

Figure 5.

a) Au content in liver and urine of mice injected with CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs and 5 nm AuNPs-PEG2K/PSMA-1 at 24 h post injection, as determined by ICP-MS (data are presented as mean ± SD. n = 3; two-tailed t-test: **P < 0.05); In vivo 3D CT images of the digestive system of mice injected with b) CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs and c) 5 nm AuNPs-PEG2K/PSMA-1 at 24 h post injection, showing more accumulation of 5 nm AuNPs-PEG2K/PSMA-1 in the gut than that measured for CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs.

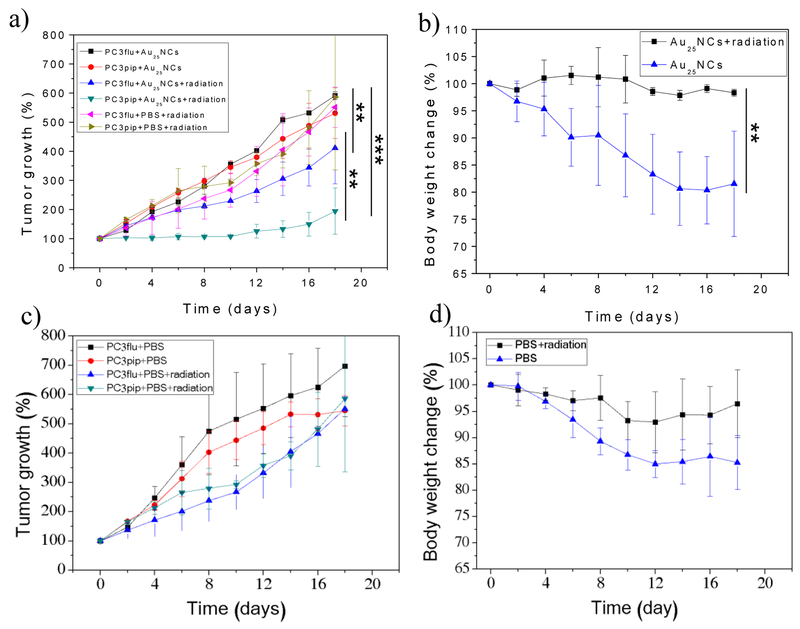

Highly encouraged by the excellent in vitro and in vivo tumor targeting of the CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs, we investigated the potential use of these agents as radiosensitizers for prostate tumor radiation therapy. Nude mice bearing both PC3pip and PC3flu tumors were divided into four treatment groups: (a) PBS injection only; (b) PBS injection with X-ray radiation; (c) CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs injection only; (d) CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs injection with X-ray radiation. Where indicated, a radiation dose of 6 Gy was given to each animal group 4 hours after injection of the sensitizer to take advantage of the peak accumulation in the tumor (Figure 4b), and also Au in blood has also dropped down to a low level at 4 h. The tumor sizes and body weights of the studied mice were monitored over 18 days (Figure. 6). Mice irradiated after injection with CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs showed a significant decrease in the rate of tumor growth, with tumor size increasing by only 94% at day 18. The mice also kept a more stable body weight. Compared to the PBS controls, the CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs also enhanced the sensitivity of PC3flu tumors to irradiation with tumor volume increasing 311% by day 18. However, this occurred to a significantly lesser extent than for the PC3pip cells (Figure. 6) and is likely due to passive EPR accumulation. In mice that only received CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs but no X-ray treatment, the PC3pip and PC3flu tumors shared similar growth kinetics and their growth was comparable to the mice injected with PBS only, with tumor volume increasing about 430%. Irradiation in the presence of targeted NCs stabilized the body weight of the animals which otherwise decreased significantly if the animals were not irradiated, dropping by 19%. A similar observation was made for the body weights of PBS-administered mice with/without radiation. Clearly, radiotherapy, sensitized by PSMA-targeted Au25NCs, enhanced the tumor growth inhibition and therapeutic outcome, as evidenced by the stabilized body weights.

Figure 6.

Tumor growth curves and body weight changes of mice after treated with a, b) CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs only and both CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs and 6 Gy radiation, and c, d) PBS only and both PBS and 6 Gy radation. For comparison, tumor growth curves of mice injected with PBS and radiation were also plotted in a). (data are presented as mean ± SD. n = 3; two-tailed t-test: **p≤0.05, ***p≤0.01).

In summary, this work demonstrates the synthesis and selective targeting of gold nanoclusters to prostate cancer cells that express the targeted biomarker. We developed a target-specific sensitizer for prostate cancer radiation therapy based on the prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) targeting ligand, CY-PSMA-1. The targeting peptide had a high affinity to PSMA-expressing cancer cells, indicating that the additional Try and Cys residues in the ligand, necessary for the formation of the PSMA-targeted radiosensitizing Au25NCs, did not alter the affinity of the ligand. The targeted gold nanoclusters demonstrated higher PSMA affinity than the CY-PSMA-1 alone and were rapidly taken up by prostate tumors to approximately 9% ID/g tissue, while, at the same time, being quickly renally excreted. Compared to PSMA-targeted 5nm gold nanoparticles there was much lower liver uptake as well. Targeting is selective for PSMA-receptor expressing prostate cancer cells, more efficient compared to a passive EPR-driven therapy approach, and significantly improved the radiation therapy of tumors in mice. This approach significantly enhances the successful outcome of radiation therapy and holds promise for even further optimization in the future. With high prostate cancer targeting specificity and fast renal clearance, the presented CY-PSMA-1-Au25NCs are very promising as radiosensitizers for prostate cancer therapy. Although limited in scope these studies do demonstrate the potential utility of targeted gold nanoclusters as radiosensitizing agents. Further studies will be required to ascertain more complete toxicity, biodistribution, and dosing schedules, particularly in larger animal models, before clinical translation can be considered.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute of Health Grant, RO1 EB020353–03. The authors also thank Mr. John Mulvihill for the help with radiation experiments. J.P.B. is a fellow of the National Foundation for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Dong Luo, Department of Radiology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA.

Xinning Wang, Department of Radiology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA,; Department of Biomedical Engineering, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA

Sophia Zeng, Department of Radiology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA,; Department of Chemistry, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA,

Gopalakrishnan Ramamurthy, Department of Radiology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA,.

Clemens Burda, Department of Chemistry, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA,.

James P. Basilion, Department of Radiology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA

References

- [1].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A, CA Cancer J. Clin 2018, 68, 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wang X, Tsui B, Ramamurthy G, Zhang P, Meyers J, Kenney ME, Kiechle J, Ponsky L, Basilion JP, Mol. Cancer Ther 2016, 15, 1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zhu S, Gu Z, Zhao Y, Adv. Ther 2018, 1, 1800050. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Song G, Cheng L, Chao Y, Yang K, Liu Z, Adv. Mater 2017, 29, 1700996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hainfeld JF, Dilmanian FA, Slatkin DN, Smilowitz HM, J. Pharm. Pharmacol 2008, 60, 977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Goswami N, Luo Z, Yuan X, Leong DT, Xie J, Mater. Horiz 2017, 4, 817. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zhang XD, Luo Z, Chen J, Shen X, Song S, Sun Y, Fan S, Fan F, Leong DT, Xie J, Adv. Mater 2014, 26, 4565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ma N, Liu P, He N, Gu N, Wu FG, Chen Z, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 31526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Antosh MP, Wijesinghe DD, Shrestha S, Lanou R, Huang YH, Hasselbacher T, Fox D, Neretti N, Sun S, Katenka N, Cooper LN, Andreev OA, Reshetnyak YK, PNAS 2015, 112, 5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Deng W, Chen W, Clement S, Guller A, Zhao Z, Engel A, Goldys EM, Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 2713; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sung W, Ye SJ, McNamara AL, McMahon SJ, Hainfeld J, Shin J, Smilowitz HM, Paganetti H, Schuemann J, Nanoscale 2017, 9, 5843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Khlebtsov N, Dykman L, Chem. Soc. Rev 2011, 40, 1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Du B, Jiang X, Das A, Zhou Q, Yu M, Jin R, Zheng J, Nat. Nanotechnol 2017, 12, 1096; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zheng J, Nicovich PR, Dickson RM, Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 2007, 58, 409; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Choi S, Dickson RM, Lee JK, Yu J, Photoch Photobio Sci. 2012, 11, 274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhang XD, Chen J, Luo Z, Wu D, Shen X, Song SS, Sun YM, Liu PX, Zhao J, Huo S, Fan S, Fan F, Liang XJ, Xie J, Adv. Healthc. Mater 2014, 3, 133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].a) Zhang P, Yang XX, Wang Y, Zhao NW, Xiong ZH, Huang CZ, Nanoscale 2014, 6, 2261; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kunjachan S, Detappe A, Kumar R, Ireland T, Cameron L, Biancur DE, Motto-Ros V, Sancey L, Sridhar S, Makrigiorgos GM, Berbeco RI, Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 7488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [15].Mansoori GA, Brandenburg KS, Shakeri-Zadeh A, Cancers 2010, 2, 1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Calais J, Czernin J, Cao M, Kishan AU, Hegde JV, Shaverdian N, Sandler K, Chu FI, King CR, Steinberg ML, Rauscher I, Schmidt-Hegemann NS, Poeppel T, Hetkamp P, Ceci F, Herrmann K, Fendler WP, Eiber M, Nickols NG, J. Nucl. Med 2018, 59, 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Emmett L, Willowson K, Violet J, Shin J, Blanksby A, Lee J, J. Med. Radia. Sci 2017, 64, 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mangadlao JD, Wang X, McCleese C, Escamilla M, Ramamurthy G, Wang Z, Govande M, Basilion JP, Burda C, ACS Nano 2018, 12, 3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wang J, Liu G, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Du B, Yu M, Zheng J, Nat. Rev. Mater 2018, 3, 358. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Xu J, Yu M, Carter P, Hernandez E, Dang A, Kapur P, Hsieh JT, Zheng J, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 13356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Tan YN, Lee JY, Wang DIC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 5677; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dixon JM, Egusa S, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].a) Wu Z, Gayathri C, Gil RR, Jin R, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 6535; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang Y, Cui Y, Zhao Y, Liu R, Sun Z, Li W, Gao X, Chem. Commun 2012, 48, 871; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Dass A, Stevenson A, Dubay GR, Tracy JB, Murray RW, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 5940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].a) Butterworth KT, McMahon SJ, Currell FJ, Prise KM, Nanoscale 2012, 4, 4830; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Her S, Jaffray DA, Allen C, Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 2017, 109, 84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zheng M, Morgan-Lappe SE, Yang J, Bockbrader KM, Pamarthy D, Thomas D, Fesik SW, Sun Y, Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 7570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Xu J, Yu M, Peng C, Carter P, Tian J, Ning X, Zhou Q, Tu Q, Zhang G, Dao A, Jiang X, Kapur P, Hsieh JT, Zhao X, Liu P, Zheng J, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Liu J, Yu M, Zhou C, Yang S, Ning X, Zheng J, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 4978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Liang G, Jin X, Zhang S, Xing D, Biomaterials 2017, 144, 95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tsvirkun D, Ben-Nun Y, Merquiol E, Zlotver I, Meir K, Weiss-Sadan T, Matok I, Popovtzer R, Blum G, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 12010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.