Background

Radical hysterectomy (Wertheim’s hysterectomy) and pelvic lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer are intricate surgeries. The principle of Wertheim’s hysterectomy is to remove the uterus and the cervix with adequate parametrium and vagina. Adequacy of surgery and careful selection of cases are very important to minimize dual modality treatment which is radical surgery followed by pelvic radiation or chemoradiotherapy. Dual modality treatment increases morbidity and wastage of resources without major benefits in oncological outcomes. The complexity in Wertheim’s surgery is mainly in the area of dissection of the ureter till its insertion so that the adequate parametrium and vaginal margins are obtained which forms the basis of optimal surgery. Dissection of the pelvic ureter along its course has a learning curve similar to someone trying to walk on a rope above a lake! This is mainly because ureters are wrapped on all sides by vessels in the parametrium supplying the uterus, vagina, bladder, and rectum. Pelvic lymphadenectomy can be a fairly avascular procedure if lymph nodes are carefully dissected looking for anatomical branches from iliac vessels.

Interestingly, the troublesome bleeders in Wertheim’s hysterectomy are generally not from the arteries but are almost always from the veins in the pelvis. The general rule that veins accompany arteries applies more for large vessels like the iliac vessels. However, the smaller arteries and veins tend to take their own course and not necessarily be huddled together all the time.

The learning curve exists both for open and minimal access approaches although venous bleeders are more cumbersome to tackle in minimal access surgery. Hence, a longer learning curve is needed to master the surgical technique. The general principle of nerve sparing radical hysterectomy is based on the identifying veins in the parametrium in and around the uterus and bladder so that nerves can be identified and spared.

Surgical Anatomy, Aberrations, Localization, and How to Avoid Bleeding

Veins Encountered During Pelvic Lymphadenectomy

External iliac vein (EIV)

Large vein of the pelvis which joins the internal iliac vein (IIV) to form the common iliac vein (CIV)

It is the continuation of the common femoral vein above the inguinal ligament

Runs posteromedial to the external iliac artery

Important tributaries are the inferior epigastric and deep circumflex iliac veins

Surgical approach: Identification of EIV is fairly easy. Opening the posterior leaf of the broad ligament by incising the peritoneum between the round ligament and the infundibulopelvic ligament will expose the psoas muscle laterally. The genitofemoral nerve and external iliac artery are identified first from lateral to medial side. Medial to the external iliac artery is the EIV. Bleeding from EIV is rare but can happen during removal of lymph nodes which are densely adherent to the vein. This vein is generally collapsed during minimal access surgery; so, care should be taken while teasing and cauterizing the lymphatic tissue, as the vein may get pulled inadvertently along with the lymphatic tissues during dissection (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12).

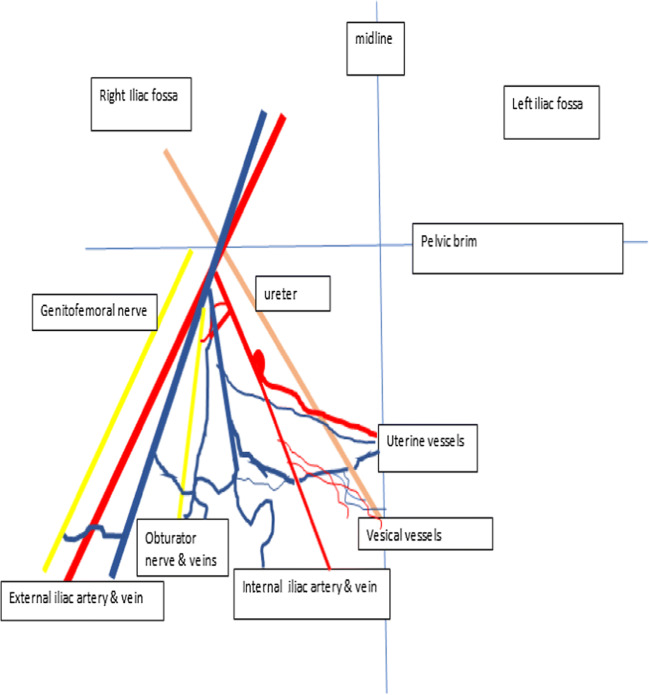

Fig. 1.

Line diagram of the pelvic side wall showing the relationship of the accessory obturator vein

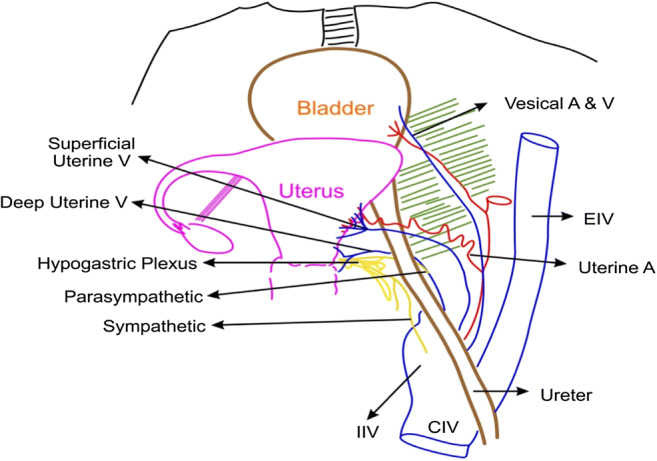

Fig. 2.

Line diagram of the pelvis demonstrating the relationship of the ureter with the uterine veins

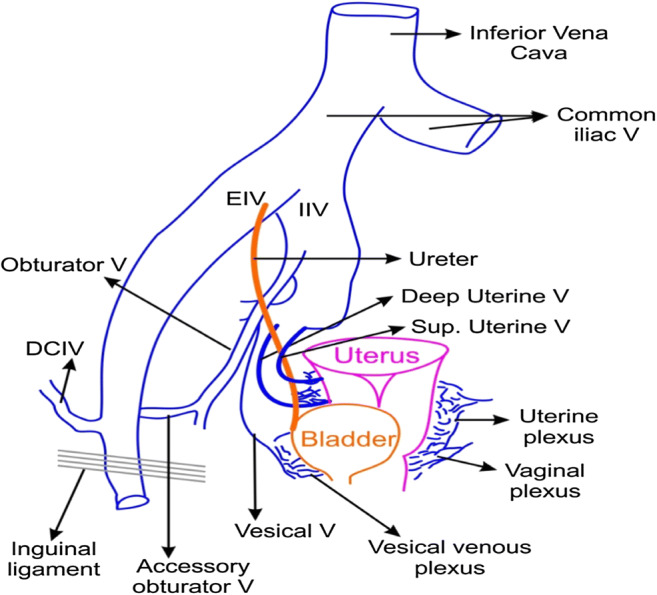

Fig. 3.

Line diagram of the uterine vessels and nerves and their relationship with the ureter

Fig. 4.

Line diagram depicting the major pelvic veins and their drainage pathways

Fig. 5.

One point perspective of the major pelvic vasculature. First 2–3 cm below the pelvic brim has major vessels very closely triagulating each other from one point. Further down, the branches and tributaries of these major vessels traverse long distances to supply the midline pelvic structures making the lower half of the pelvis an area of large vascular network causing troublsome venous bleeding

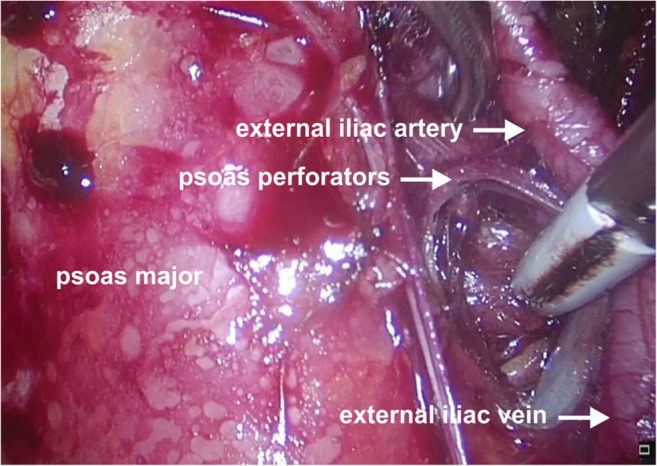

Fig. 6.

Operative photo depicting the perforators of the psoas major in relation to the external iliac vessels

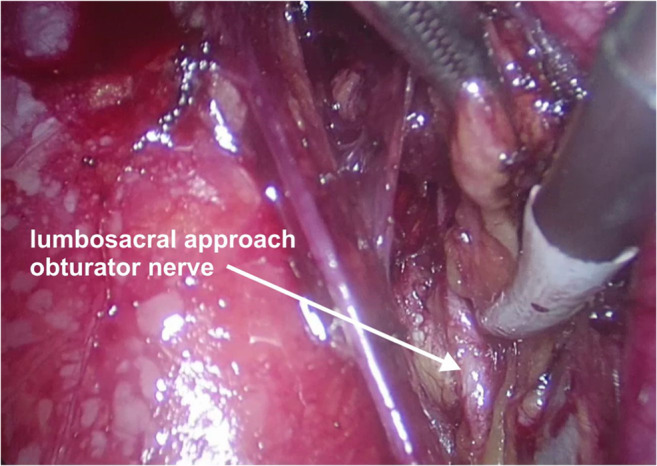

Fig. 7.

Operative photo depicting the obturator nerve

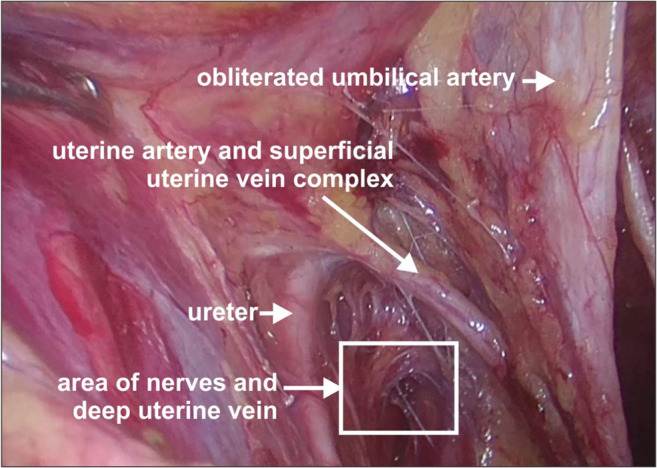

Fig. 8.

Operative photo depicting the superficial uterine vein and uterine artery crossing the ureter from above

Fig. 9.

Operative photo depicting the perforator veins over the obturator internus muscle at the pelvic side wall

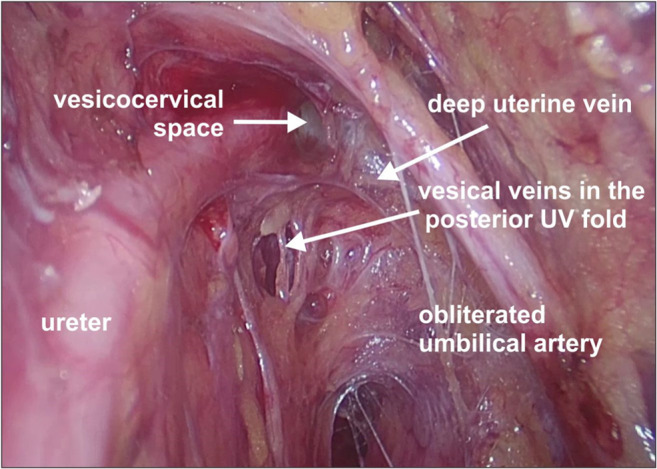

Fig. 10.

Operative photo depicting the deep uterine and vesical veins

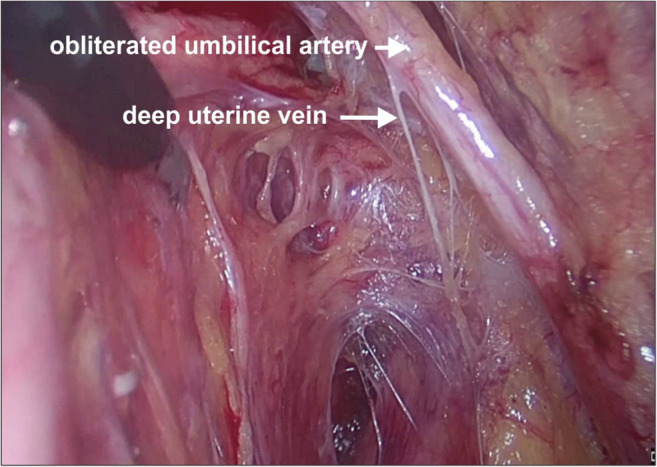

Fig. 11.

Operative photo depicting the deep uterine vein

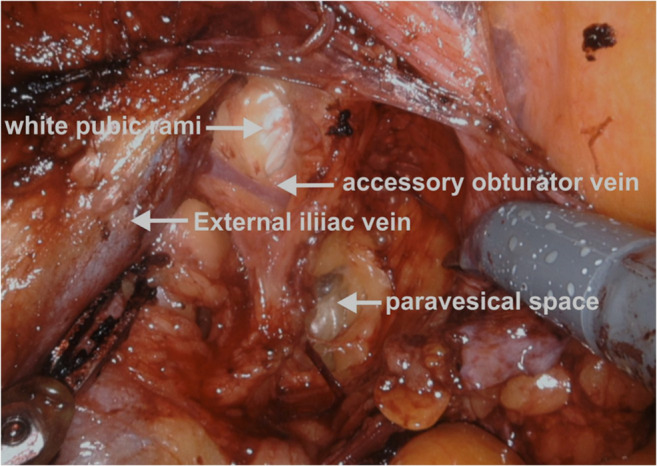

Fig. 12.

Operative photo depicting the accessory obturator vein joining the external iliac vein

Another point of bleeding from EIV during lymphadenectomy is at the insertion of the accessory obturator vein which joins the EIV from an inferior angle. The bleeding at this level is difficult to suture in minimal access surgery as it is often difficult to visualize the undersurface of the EIV. It is preferable to clip the accessory obturator vein if the lymph node is large and obscuring the vein to prevent troublesome bleeding.

-

2.

Deep circumflex iliac vein

Formed by the union of the venae comitantes of the deep iliac circumflex artery

Joins the external iliac vein about 2 cm above the inguinal ligament

Receives small branches from the thoracoepigastric vein

Surgical approach: This vein is encountered while doing the distal limit of pelvic lymphadenectomy. It traverses superficial to the external iliac artery and sits snugly on the artery before joining the external iliac vein. There is an enlarged, mostly reactive, lymph node in this area (distal iliac node) which obscures this vein along with some fatty tissue. Carefully teasing the lymph node by traction (upwards and outwards) will separate the node from the iliac vessels and reveal this vein. The lymphatic tissue should be clipped before removal of the distal iliac node as small veins superolateral to the iliac vessels can bleed and obscure the surgical field (Fig. 4).

-

3.

Obturator vein

It begins in the of the adductor region of the thigh entering the pelvis through the upper part of the obturator foramen

Ascends along the lateral wall of the pelvis below the obturator artery passing between the ureter and the internal iliac artery

Drains into the IIV

Communicates with the external iliac vein via the abnormal obturator vein

Surgical approach: The obturator vein runs parallel and just below the obturator nerve in the fossa. Following the identification of the pubic rami in the lateral paravesical space, the obturator nerve and obturator vessels are found just at the inferior border of the pubic rami on the lateral pelvic wall. The obturator vein is very close to the obturator nerve at this point and separates slightly as it gets closer to the internal iliac vein. This vein can be injured while dissecting the enlarged obturator nodes. It is important to identify the obturator nerve first so that the vein can be clipped when necessary, and inadvertent clipping, cutting, or cautery burn to the nerve can be prevented (Figs. 1, 4, and 5).

-

4.

Accessory obturator vein

This vein connects the obturator and external iliac veins at the inner surface of the pubis

It is also called the “venous corona mortis” or “ring of death” by various authors due to the increased risk of bleeding as a result of accidental injury during surgical procedures

The incidence quoted in the literature is variable ranging from 25 to 95%. Table 1 depicts the various studies quoting the incidence of this vein

In a meta-analysis of 21 studies (that included 2184 hemi-pelvises) [10], the presence of the venous corona mortis was more prevalent than its arterial counterpart (41.7% vs. 17.0%). The incidence of the combined arterial and venous corona mortis was seen in 15.2% and bilaterality in 17.9%

In another study of 20 human adult cadavers (that included 40 hemi-pelvises) [7], the venous corona mortis was classified as follows: type I, the obturator vein drains into the external iliac vein; type II, the obturator vein drains into the inferior epigastric vein; and type III, venous anastomosis of the obturator and inferior epigastric veins

Table 1.

Incidence of the venous corona mortis in selected studies

Surgical approach: The best possible way to identify the accessory obturator vein is to dissect the lateral paravesical space first. The lateral paravesical space is fairly avascular and is lateral to the obliterated hypogastric artery. The dissection is carried out inferolaterally holding the obliterated hypogastric artery anterior to the bladder. During the dissection, the surgeon can see and feel the bony pubic rami anteriorly which appear as a white glistening area. The accessory obturator vein can be seen running vertical on the pubic rami connecting the external iliac vein or circumflex iliac vein above and the obturator vein below. The vein runs in the anterior aspect of the obturator fossa before it joins the obturator vein just below the pubic rami (Figs. 1, 4, 9, and 12).

Care should be taken to identify the vein as it can bleed while dissecting the lateral paravesical space or during removal of the obturator nodes. If there are enlarged nodes in the area, it is preferable to clip the vein on both ends to minimize bleeding. Identification of both the external iliac vein and the obturator nerve and obturator vein is preferable prior to clipping the vein.

-

5.

Internal iliac vein (IIV)

Lies lateral and inferior to the internal iliac artery (IIA) and receives all tributaries that correspond to arterial branches of the IIA except for the umbilical and iliolumbar veins which drain into the liver and common iliac veins, respectively

The superior gluteal vein is the largest tributary

It joins the external iliac vein to form the common iliac vein

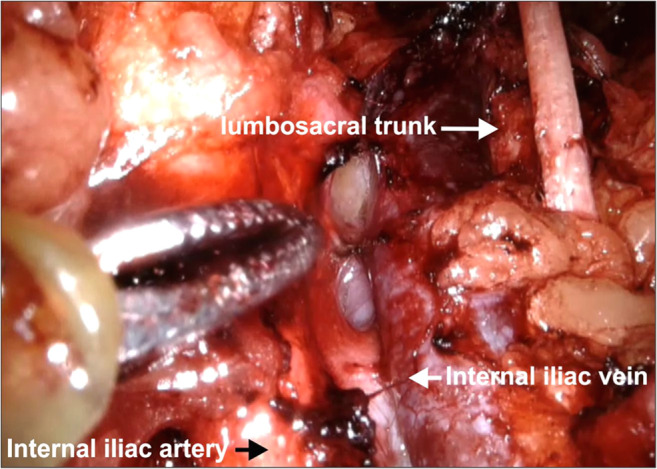

Surgical approach: The process of clearing the lymph nodes on the external iliac vein and obturator fossa to expose the obturator nerve is essential to visualize the internal iliac vein clearly during surgery. Bleeding in the obturator fossa is generally in this area because of the venous confluence. The safest way to remove lymphatics is the lumbosacral approach where dissection between the psoas major and external iliac vessels is performed (Fig. 7). This approach separates all the lymphatics from the lateral pelvic wall at the level of the confluence of EIV and IIV taking care of the psoas perforators. Separated lymphatics can then be disconnected from the proximal part of the obturator fossa without causing bleeding. This will reveal the internal iliac vein making further lymphatic dissection easy if needed (Figs. 1, 2, 4, 5, and 13).

-

6.

Venous perforators

Fig. 13.

Operative photo depicting the internal iliac vein

The important venous perforators which are liable to bleed during lymph node dissection include perforators penetrating the psoas major and obturator internus muscles (Figs. 6 and 9).

Surgical approach: While approaching the obturator fossa through the lumbosacral approach (from above), care must be taken to cauterize the psoas perforators between the muscle and EIV. While removing the lymph nodes from the obturator fossa, care must be taken to cauterize or clip the perforators from the obturator internus muscle especially at the confluence of EIV and IIV. These tiny thinned wall perforator vessels retract within the muscles preventing effective control by the cautery. If these vessels cannot be sealed, pressure gauze with a wait and watch of 5–10 min will usually stop the bleeding.

Veins Encountered During Radical Hysterectomy

Uterine veins

Include the superficial and deep uterine veins

The superficial uterine vein lies superficial to the ureter and runs parallel to the uterine artery; the deep uterine vein is inferior and perpendicular to the ureter. All the uterine veins cross the ureter to form a plexus on the lateral wall of the uterus (Fig. 8)

In a study of 15 cadavers [11], the deep uterine vein was present in the upper region of the cardinal ligament having three to six multiple branches. These included one or two cervical branches and two to four vesical branches

The deep uterine vein is suggested to be an anatomical landmark during surgery and to preserve the pelvic splanchnic nerves. Laparoscopic type C1 hysterectomy is based on the anatomic landmark of the deep uterine vein and its branches and corresponds with the inferior limit of the dissection [12–15] (Figs. 10 and 11)

Surgical approach: The best possible approach to identifying the superficial uterine vein is to identify the uterine artery at its origin. Holding the obliterated hypogastric artery, the uterine artery is identified as a branch (with a knuckle) arising from the internal iliac artery. The uterine artery can sometimes be confused with the superior vesical artery as both branches traverse the parametria towards the uterus and bladder. The uterine artery is the first artery to cross the ureter anteriorly, has a knuckle at its origin, tortuous, and also bigger than the superior vesical artery. The superficial uterine vein follows the uterine artery along its course initially from the uterus but dips inferiorly to join the internal iliac vein 1–2 cm before the origin of the uterine artery. Clamping the uterine artery alone at its origin and retracting it towards the uterus cause bleeding from the superficial uterine vein. To prevent this bleeding, it is preferable to dissect the uterine artery above the ureteric tunnel till its origin and identify the superficial uterine vein so that they can be clipped separately before cutting. In minimal access surgery, it is preferable to keep the hammock-like uterine vessels without cutting till the complete dissection of the ureteric tunnel is done as unnecessary assistance is needed to hold the cut end of the vessels (Figs. 2, 3, and 5).

The best approach to identify the deep uterine vein is to dissect the Okabayashi space. This space is just inferolateral to uterosacral and below the ureter. In this space, the inferior hypogastric nerve runs parallel and inferior to the uterosacral ligaments and converges with the parasympathetic to form the inferior hypogastric plexus. In this space, the deep uterine vein is found below the ureters, traversing the parametrium towards the uterus. Just below and very close to the deep uterine vein is the parasympathetic nerve (S1.2.3) which converges into the inferior hypogastric plexus. The deep uterine vein is larger than the superficial vein and drains into the internal iliac vein. The deep uterine vein can also be identified from the internal iliac vein during lymphadenectomy but might cause bleeding as multiple veins are draining into the internal iliac vein in the lateral pelvic wall.

-

2.

Uterine venous plexus

Lies on either side of the uterus between the layers of the broad ligament

Drain through the uterine veins into the internal iliac vein

Communicate with the pampiniform plexus and thence into the ovarian veins

Continuous with the vaginal venous plexus (called the uterovaginal venous plexus)

The vaginal plexus lies on either side of the vagina and within the mucosa, which are thin walled and numerous

Surgical approach: Since the venous plexus is very close to the uterus, they cannot be separately seen during Wertheim’s hysterectomy. The clamping of the parametrium is done lateral to these veins even before they have formed the plexus; hence, the chances of injury are less. Sometimes, there could be back-bleeders from the uterus caused by the plexus which can be easily managed by applying clamps on the specimen side (Fig. 4).

-

3.

Veins draining the ureter

Highly variable and include renal, gonadal, vesical, and uterine veins

These veins form a thin plexus all along the ureter

Surgical approach: It is preferable to leave a thin fold of tissue along with the plexus while dissecting the ureter so as not to devascularize the ureter. While dissecting the ureteric tunnel, usually there is a small vein and artery supplying the ureter which drains into the uterine artery vein bundle. This needs to be identified and carefully coagulated away from the ureter to prevent troublesome bleeding in the tunnel and diathermy injury to the ureter.

-

4.

Descending cervical vein

The descending cervical vein runs perpendicular to the uterine vessels and drains into the uterine vein anteriorly in the uterovesical (UV) fold. Many vesical veins drain into the descending cervical vein anteriorly.

Surgical approach: Bleeding is encountered while dissecting the UV fold of the peritoneum and while separating the bladder from the cervix and vagina anteriorly. It preferable to separate the bladder in the midline first and then ligate the uterine vessels before separating the bladder anterolaterally. This prevents unnecessary bleeding from the descending cervical vein.

-

5.

Vesical veins

Veins in the pelvis that drain blood from the urinary bladder

Include the superior and inferior vesical veins

The inferior vesical vein receives blood from the bladder and deep dorsal vein

The vesical veins receive blood from the vesical venous plexus and drain into the internal iliac vein

Surgical approach: The vesical veins which cause troublesome bleeding are found while dissecting the bladder pillar on the anterolateral part of bladder. This tissue along with the vessels and nerves forms the anterior parametrium. The bladder pillar or the UV fold has two parts: the anterior UV fold which is anterior to the ureter and the posterior UV fold which is posterior to the ureter. Dissection of bladder pillar is necessary to obtain the adequate anterior parametrium and to free the ureter completely from the lateral aspect of the cervix so that adequate vaginal margins can be obtained (Figs. 2, 4, 5, and 10).

Following dissection of the uterine vessels in the ureteric tunnel, further dissection above the ureter reveals the white uterocervical space. Dissecting this space pushes the anterior UV fold up which is then ligated and cut to clearly reveal the insertion of the ureter into the bladder anteriorly. Generally, two vesical veins traverse the posterior leaf of the bladder pillar to join the deep uterine vein. Autonomic nerves supplying the bladder and uterus are present in this fold. This space is described as the Yakubi space or the fourth space in nerve sparing radical hysterectomy.

-

6.

Vesical venous plexus

It surrounds the pelvic part of the urethra and bladder neck

Receives the dorsal vein of the clitoris

Communicate with the uterine and rectal plexuses via the vaginal veins

Drains by several small vesical veins into the deep uterine vein, descending cervical vein, or internal iliac vein

Surgical approach: Securing the superficial and deep uterine veins prior to dissection of the anterior parametrium as described above generally prevents troublesome bleeding from the vesical veins. Further, clamping the anterior parametrium prevents bleeding from the anterior vesical veins. Clamping the posterior UV fold is difficult as the nerves in the posterior UV fold need to be preserved, so clamping the deep uterine vein and dissecting this space reduce bleeding from the two vesical veins. They can be individually identified and clipped as well if feasible (Fig. 4).

-

7.

Ovarian veins

Present in the infundibulopelvic ligament

Drain the corresponding ovaries into the IVC (right) or the left renal vein (left)

Surgical approach: If salpingo-oophorectomy is planned, clamping the infundibulopelvic ligament easily prevents bleeding from these veins. However, if the ovary is preserved during hysterectomy in young patients, troublesome bleeding and hematoma in the posterior broad ligament can occur. Care should be taken to clamp the uterine side of the adnexa to prevent such troublesome hematoma and bleeding which will jeopardize ureteric dissection in the posterior leaf of the broad ligament.

Conclusion

Knowledge of venous anatomy of the pelvis can aid the surgeon in avoiding troublesome venous bleeding during surgery which consequently reduces blood loss and decreases transfusion rates and operative time. This comprehensive review can guide trainees and surgeons in practice to identify and safeguard the pelvic veins during radical hysterectomy.

Acknowledgments

We extend our appreciation towards Mr. Nilesh Ganthade and Mr. Kuldeep Save, Department of Medical Graphics, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, for providing the line diagrams and digital photographs for the manuscript.

Author Contributions

TS Shylasree: Protocol development; data analysis; manuscript writing/editing

AK Kattepur: Data analysis; manuscript writing/editing

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

T. S. Shylasree, Email: shyla_sree@hotmail.com

Abhay K. Kattepur, Email: drabhay1985@gmail.com

References

- 1.Moore KL, Dalley AF, Agur AMR (2013) Clinically oriented anatomy, 7thed, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins

- 2.Romanes GJ (1986) Cunningham’s manual of practical anatomy: Vol 2 (Thorax and abdomen), 15thed, Oxford medical publications

- 3.Tornetta P, Hochwald N, Levine R. Corona mortis: incidence and location. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;329:97–101. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199608000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Missankov AA, Asvat R, Maoba KI. Variations of the pubic vascular anastomoses in black South Africans. Acta Anat. 1996;155:212–214. doi: 10.1159/000147807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okcu G, Erkan S, Yercan H, Ozic U. The incidence and location of corona mortis: a study on 75 cadavers. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75(1):53–55. doi: 10.1080/00016470410001708100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berberoğlu M, Uz A, Ozmen MM, Bozkurt MC, Erkuran C, Taner S, et al. Corona mortis: an anatomic study in seven cadavers and an endoscopic study in 28 patients. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(1):72–75. doi: 10.1007/s004640000194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rusu MC, Cergan R, Motoc AG, Folescu R, Pop E. Anatomical considerations on the corona mortis. Surg Radiol Anat. 2010;32(1):17–24. doi: 10.1007/s00276-009-0534-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Namking M, Woraputtaporn W, Buranarugsa M, Kerdkoonchorn M, Chaijarookhanarak W. Variation in the origin of the obturator artery and corona mortis in Thai. Siriraj Medical Journal. 2007;59:12–15. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pillay M, Sukumaran TT, Mayilswamy M. Anatomical considerations on surgical implications of corona mortis: an Indian study. Ital J Anat Embryol. 2017;122(2):127–136. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanna B, Henry BM, Vikse J, Skinningsrud B, Pękala JR, Walocha JA, et al. The prevalence and morphology of the corona mortis (crown of death): a meta-analysis with implications in abdominal wall and pelvic surgery. Injury. 2018;49(2):302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li H, Jia J, Xiao Y, Kang L, Cui H. Anatomical basis of female pelvic cavity for nerve sparing radical hysterectomy. Surg Radiol Anat. 2015;37(6):657–665. doi: 10.1007/s00276-014-1405-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Díaz-Feijoo B, Bradbury M, Pérez-Benavente A, Franco-Camps S, Gil-Moreno A (2018) Nerve-sparing technique during laparoscopic radical hysterectomy: critical steps. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.01.034 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Liang MR, Han DX, Jiang W, Liu H, Li L, Zhong ML, et al. Laparoscopic type C1 hysterectomy based on the anatomic landmark of the uterus deep vein and its branches for cervical cancer. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2018;40(4):288–294. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3766.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyo S, Mizumoto Y, Takakura M, Nakamura M, Sato E, Katagiri H, et al. Nerve-sparing abdominal radical trachelectomy: a novel concept to preserve uterine branches of pelvic nerves. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;193:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujii S, Takakura K, Matsumura N, Higuchi T, Yura S, Mandai M, Baba T. Precise anatomy of the vesico-uterine ligament for radical hysterectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]