Abstract

The current study represents the first longitudinal investigation of the potential effects of breastfeeding duration on maternal sensitivity over the following decade. This study also examined whether infant attachment security at 24 months would mediate longitudinal relations between breastfeeding duration and changes in maternal sensitivity over time. Using data from 1,272 families from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development, we found that longer breastfeeding duration (assessed up to age 3) predicted increases in observed maternal sensitivity up to child age 11, after accounting for maternal neuroticism, parenting attitudes, ethnicity, maternal years of education and presence of a romantic partner. Additionally, secure attachment at 24 months was predicted by breastfeeding duration, but it did not act as a mediator of the link from breastfeeding duration to maternal sensitivity in this study. Generating a more specific understanding of how breastfeeding impacts the mother-child dyad beyond infancy will inform recommendations for best practices regarding breastfeeding.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, maternal sensitivity, attachment

Children who were breastfed as infants show multiple positive outcomes, including higher cognitive competence, fewer health problems, and higher communication scores than children who were not breastfed (Oddy et al., 2011). Benefits for the infant immune system from breastfeeding have also been well-established (Xanthou, 1998), and research has further indicated long-term protection against disease and obesity for children (Hoddinott, Tappin, & Wright, 2008). Quinn and colleagues (2001) also found a significant effect of breastfeeding duration on child cognitive development, after accounting for a range of biological and psychosocial factors. Breastfeeding also offers positive health benefits for mothers, such as lowering risks for ovarian and breast cancer rates (Godfrey & Lawrence, 2010; Mezzacappa & Katkin, 2002; U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). Studies have also established a link between longer duration of breastfeeding and mothers’ lower postpartum depressive symptoms, suggesting that the practice of breastfeeding may be protective for new mothers (Hahn-Holbrook, Haselton, Schetter, & Glynn, 2013; Akman et al., 2008). Mothers caregiving also appears to be related to breastfeeding, as several studies have demonstrated a relationship between breastfeeding and mothers’ display of sensitive caregiving with their infants (Bigelow et al., 2014; Edwards, Thullen, Henson, Lee, & Hans, 2015; Kim et al., 2011; Kuzela, Stifter, & Worobey, 1990; Papp, 2013; Tharner et al., 2012). However, research establishing the extent to which breastfeeding may influence parenting behaviors longitudinally, and the stability of this relationship beyond infancy, is lacking. This gap in the literature is important given that breastfeeding is highly recommended for families with young children (Eidelman & Schanler, 2012). The current study addresses the link between the number of weeks mothers breastfeed their infant (breastfeeding duration) and changes in their sensitivity toward their child over the following decade. We further examine whether child attachment may mediate the relationship between breastfeeding duration and maternal sensitivity.

In infancy, maternal sensitivity refers to the synchronous timing of a mother’s responsiveness to her baby, her affect, flexibility, and ability to read her infants’ cues (Johnson, 2013; Leerkes, Weaver, & O’Brien, 2012). As the child grows, sensitivity continues to reflect an ability to participate in a synchronous relationship, and incorporates age-appropriate behaviors such as respect for autonomy, supportive presence, and withholding hostility (Owen, Klausli, & Murrey, 2000). In the postpartum period, breastfeeding is frequently promoted as a way to increase maternal sensitivity, although multiple authors have noted that the positive emotional bonding between mother and infant often promoted as a breastfeeding benefit has not been tested empirically (Golding, Rogers, & Emmett, 1997; Jansen, de Weerth, & Riksen-Walraven, 2008; Schulze & Carlisle, 2010; Tharner et al., 2012). There is, however, theoretical support for the expectation that breastfeeding might be related to the mother-infant relationship. Breastfeeding has been linked to both activation of brain-regions associated with caregiving (Kim et al., 2011) and with the release of oxytocin, a critical hormone linked to social competence and adequate caregiving behaviors (Mohberg & Prime, 2013). Observations of breastfeeding versus non-breastfeeding mothers also suggests behavioral differences between the two. For example, breastfeeding mothers score higher on positive maternal interactions when feeding their infants and in free play situations, and currently-breastfeeding mothers display more maternal touch (Bigelow et al., 2014; Kuzela, Stifter, & Worobey, 1990). Additionally, breastfeeding mothers spend more time in close interactive behaviors with their infants, which may promote maternal sensitivity (Smith & Ellwood, 2011; Smith & Forester, 2017). In sum, the longer a mother breastfeeds, the longer she is exposed to both biological and situational factors that promote parent-offspring bonding and parental investment. What is unknown is the degree to which these biological and situational factors scaffold sensitive parenting beyond the immediate interaction. For example, if the release of hormones like oxytocin or vasopressin during breastfeeding increases emotional bonding between mother and child and subsequent caregiving behavior, it would be most evolutionarily adaptive for that promotive influence to extend past infancy. Were breastfeeding duration to facilitate maternal sensitivity beyond the infant period, it would potentially explain the various reported long-term benefits of being breastfed including increased cognitive ability (Golding, Rogers, & Emmett, 1997; Kramer et al., 2008), lower incidence of psychopathology (Hughes & Bushnell, 1977; Schwarze, Hellhammer, Stroehle, Lieb, & Mobascher, 2014), and lower incidence of substance use (Alati, Van Dooren, Najman, Williams, & Clavarino, 2009). It is currently unknown whether breastfeeding behavior predicts changes in caregiving behavior, or the degree to which those changes are seen beyond infancy.

Consistent with the expectation that breastfeeding will have positive consequences for mother-child interactions, breastfeeding is correlated with measures related to maternal sensitivity. For example, a sample of 17 mothers who exclusively breastfed during the first month postpartum showed increased activation in brain regions associated with caregiving behaviors, which in turn was correlated with more sensitivity with their infant at 3–4 months postpartum (Kim et al., 2011). During trials in which distressed and non-distressed infant faces were shown to mothers, breastfeeding mothers were significantly more likely than bottle-feeding mothers to attend to infant distress. This difference was not evident during late pregnancy, but emerged following the experience of breastfeeding (Pearson et al., 2011).

Breastfeeding duration is also correlated with observational measures of sensitivity. Among a matched sample of young, low-income African American mothers, breastfeeding initiation was positively correlated with maternal sensitivity at four months postpartum (Edwards, Thullen, Henson, Lee, & Hans, 2015). In a larger, Dutch birth-cohort sample, longer breastfeeding duration in infancy was associated with more maternal sensitive responsiveness at 14 months (Tharner et al., 2012). Papp (2013) used the same data set employed in the present study to examine breastfeeding’s correlation with observed maternal sensitivity and found that, controlling for demographic and early relational characteristics, dichotomous breastfeeding status (currently breastfeeding or not) correlated with observed maternal sensitivity over the first three years of parenting.

The literature to date on breastfeeding and parenting behaviors is limited by not predicting change over time in maternal sensitivity. The reported correlations between breastfeeding duration and maternal sensitivity could be driven by a common cause, or selection effects. According to the selection perspective, dispositionally invested mothers are likely to both breastfeed and express sensitivity. In the present study, we seek to account for this selection perspective by including a range of important covariates, such as maternal education, presence of a partner in the home, maternal ethnicity, and child attachment to mother. We further add to these factors those of maternal neuroticism and parenting beliefs. Studies that account for such a range of selection factors and examine change over time, in which mothers’ own sensitivity is used as a control to predict increases over time, offer a stringent test of the commonly held belief that breastfeeding promotes mother-child bonding (Johnson, 2013).

Attachment as a Possible Mediator

In a further extension of our model linking breastfeeding and changes in maternal sensitivity over time, we also examined the role of attachment as a potential mediator between breastfeeding duration and maternal sensitivity. There has been a great deal of theoretical and empirical work linking maternal sensitivity with attachment outcomes (for a review see de Wolff & van Ijzendoorn, 1997), but in this study we were particularly interested in how mothers’ behaviors might change over time. Therefore, we examined whether the link between breastfeeding duration and sensitivity could be mediated by the strength of the infant attachment to the mother. According to attachment theory and research, being in close physical proximity promotes a secure infant attachment (Ainsworth, Bell, & Stayton, 1974; Anisfield, Casper, Nozyce, & Cunningham, 1990; Bowlby, 1969). In line with this, the close physical contact afforded by breastfeeding, in addition to the positive interactional qualities observed in breastfeeding mothers, might also promote a secure infant attachment (Bigelow et al., 2014; Kuzela et al., 1990). In turn, having a securely attached infant may lead to a stronger mother-infant relationship that may be evidenced by increasing sensitivity to the child’s behavior from the mother (Belsky & Fearon, 2002). In this model, breastfeeding, attachment, and sensitivity were all measured at different timepoints, allowing for a true mediational test.

Specific research on the links between breastfeeding and attachment are limited, and the results present a complicated and mixed pattern of findings (Tharner et al., 2012; also see Britton, Britton, & Gronwaldt, 2006; Kim et al., 2011; Johnson, 2013). Jansen and colleagues (2008), in a review of the literature (k = 6) on breastfeeding and the mother-infant relationship concluded there was no empirical evidence to support a claim that breastfeeding promotes either maternal bonding or infant attachment. More recently, a study of 152 mothers recruited during pregnancy and followed until their infants were 1 year of age showed no link between attachment classification at 12 months and breastfeeding initiation or duration (Britton et al., 2006). However, another study showed that mother-child pairs with 6 months of breastfeeding had higher levels of secure and lower levels of disorganized attachment scores than their counterparts who breastfed for a shorter duration, as well as the highest level of maternal sensitivity at 14 months (Tharner et al., 2012). However, both attachment and sensitivity were measured at 14 months, preventing attempts to disentangle the two. Furthermore, although the authors were interested in testing for a mediational role for maternal sensitivity, they found sensitivity to be unrelated to attachment in their sample. We extend the literature on this topic by testing for attachment security as a mediator, using a measure of attachment temporally separate from the period of breastfeeding and subsequent maternal sensitivity.

The Current Study

Consistent with dose-response evidence (e.g., linking early feeding practices and cognitive development; Quinn et al. 2001; Sloan, Stewart, & Dunne, 2010), the predictor was operationalized as breastfeeding duration. We extend prior work on parenting behaviors and breastfeeding by testing for a dose-response relation between breastfeeding duration and relative change in maternal sensitivity over the first decade of the child’s life. Recent research and theory has emphasized the importance of understanding determinants of dynamic processes in parenting (Belsky & Jaffee, 2006), suggesting, for example, that maternal sensitivity may decrease over time with children exhibiting developmental risk (Ciciolla, Crnic, & West, 2013). We extent this work that has examined determinants of trajectories of maternal sensitivity, expecting that a longer breastfeeding duration will predict relative increases in maternal sensitivity. We expect that mothers who breastfeed longer will also enjoy the positive biological, physical, and interactional benefits associated with breastfeeding for a longer period of time. We further expect the relationship between breastfeeding and maternal sensitivity to extend beyond the infant/toddler period, although no studies have specifically examined the period of time that the current study does. In sum, breastfeeding is expected to set in motion a cascade of positive mother-child interactional qualities that continue beyond the period when breastfeeding is occurring.

We include covariates linked to breastfeeding behavior. Breastfeeding mothers are frequently observed to be to be partnered and more educated than their non-breastfeeding counterparts (Gibson-Davis & Brooks-Gunn 2007; Papp, 2013; Ryan, Wenjun, & Acosta, 2002; Thulier & Mercer 2009). Also, some work has shown African American mothers to be less likely to start breastfeeding than either European American or Latina mothers (Thulier & Mercer, 2009). Additionally, dispositional qualities of mothers may differentiate breastfeeding from non-breastfeeding mothers, so we also included the mothers level of neuroticism and her parenting attitudes as covariates. Specifically, research suggests that mothers who report high levels of extroversion, emotional stability, and conscientiousness were significantly more likely to initiate and continue breastfeeding for a longer duration (Brown, 2014). Similarly, mothers who adopt an infant-led approach to feeding are more likely to breastfeed for a longer duration than those who adopt parent-led attitudes (Brown & Arnott, 2014).

Child gender was also included as a potential moderator, as research with mother-infant breastfeeding dyads has suggested a potential interaction effect between mother interaction qualities and child gender such that breastfed males and bottle-fed females may exhibit the most positive interactional qualities (Kuzela et al., 1990). Other research has also identified differences between boys and girls in related developmental and family process research (e.g., parenting practices, Sturge-Apple, Davies, Boker, & Cummings, 2004).

Method

Participants

Participants were the families in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (NICHD SECCYD). These families were recruited in 1991, shortly after their child’s birth, from hospitals at 10 sites across the United States (Little Rock, AR; Irvine, CA; Lawrence, KS; Boston, MA; Philadelphia, PA; Pittsburgh, PA; Charlottesville, VA; Morganton, NC; Seattle, WA; and Madison, WI). Specific recruitment procedures are detailed more thoroughly by the NICHD Early Child Care Research Network (ECCRN) (2005). When infants were 1 month old, 1,364 mothers completed a home interview and became part of the initial study sample. This sample included a substantial proportion of low education parents (30% had no more than a high school degree), ethnic minority families (13% were African American compared with the national proportion of 12%), and the mean income level was the same as the U.S. average ($37,000). A total of 1,272 participants had maternal sensitivity data at the first assessment and were included in analyses.

Procedures and Variables

Detailed measures of family demographics, maternal behaviors, and children’s characteristics and adjustment were obtained from multiple informants beginning when children were 1 month of age and continuing until they were 15 years old. Assessments were conducted when children were 1, 3, 6, 12, 15, 24, 36, 42, 46, 50, and 54 months old, and at ages 5, 6, 7, 9, 11, 14 and 15 years. The current study focuses on data collected between 1 month and 11 years of age. The current study was based on secondary data analysis and was therefore determined to be exempt under IRB protocol.

Parental sensitivity.

Observations of mothers’ and fathers’ sensitivity when interacting with their children were obtained eight times between the child’s birth and age 11. Videotapes of parent-child interactions involving free-play scenarios and problem-solving tasks were made at each of the study’s 10 sites and sent to a single site for central coding, with coders blind to other information about the families. Examples of the activities included, at the 6-month visit, asking mothers and their babies to play freely with a set of toys for a period of 15 minutes. At age 4.5 years, mothers and children completed a problem-solving task by playing with an etch-a-sketch that had been altered by adding a maze to the screen. Mothers and children each controlled a separate knob on the toy, and needed to work together to complete the task. Details on the specific tasks are available in previously published articles on this data set (see NICHD ECCRN, 1999, 2005). Rating scales were designed to capture the parent’s emotional and instrumental support for the child’s engagement with the task activities as well as collaborative interactions between parent and child. In order to maintain an age-appropriate measure of the construct, parental sensitivity indicators changed somewhat over time, to reflect a developmentally appropriate measure of the same construct at each time point. For assessments at 6 and 36 months, sensitivity scores reflected the sum of three 4-point ratings: sensitivity to the child’s non-distress signals, positive regard, and intrusiveness (reversed); these scores were recoded (by multiplying each by 7/4) to 7-point scales to make them comparable to observational scales obtained at later time points. The sensitivity score at 54 months and ages 5, 8 and 11 was computed as the sum of three 7-point ratings: supportive presence, respect for autonomy, and hostility (reversed). Individual ratings were combined at each age to represent parental sensitivity in the interaction tasks. Inter-coder reliability was established by having two coders assess approximately 20% of the tapes, randomly drawn from each assessment period. Additional details regarding coding procedures, training and reliabilities are available in NICHD ECCRN (1999, 2003, 2005). Observed paternal sensitivity was also measured for a subsample of families (n = 365). All sensitivity measures were reliable with alphas greater than .70. We modeled maternal sensitivity out to age 11, as this was the last assessment available for analyses.

Breastfeeding duration.

Length of breastfeeding was calculated from mothers’ reports on a series of questions. During the 1-month interview, mothers were asked if the child was ever breastfed. Mothers responding no were coded as “never breastfed,” and mothers responding yes were asked how old, in weeks, their baby was when breastfeeding had ended. At 6 months, mothers who had indicated breastfeeding at 1 month were asked if they were currently breastfeeding. Those responding no were asked how old, in months, their baby was when breastfeeding had ended. These questions were repeated until the mother reported that breastfeeding had ceased or through age 3. The majority of mothers (74.4%) reported some breastfeeding. Breastfeeding was assessed with three variables. The first two were dichotomous indicators of whether the mother was breastfeeding at 6 weeks and 6 months 0(no) 1(yes). The third breastfeeding predictor variable was a continuous variable reflecting the weeks mother breastfed. Percent of mothers who breastfed were as follows: never (28.6%), 6 weeks (50.3%), 6 months (26.4%), 9 months (16.6%), 12 months (9.7%), 18 months (2.7%), 20 months (1%). We windsorized the 2% of mothers who reported breastfeeding longer than 24 months. This winsorizing procedure reduced the influence of these extreme values on the model estimates (Wilcox, 2005). The resultant breastfeeding duration scores ranged from 1 week to 23.5 months and averaged slightly less than 17 weeks. In order to maintain temporal ordering when predicting maternal sensitivity at 6 and 15 months, we also included in the primary analyses two dichotomous indicators of whether the mother was breastfeeding at 6 weeks, and at 6 months 0(no), 1(yes).

Demographic covariates.

Demographic measures were obtained from mothers at the one-month interview. These included whether a romantic partner was in the home at 1 month, mother ethnicity (0=not Hispanic, 1=Hispanic), mother race (0=not African American, 1=African American), and mother years of education.

Maternal covariates.

At one month mothers completed the neuroticism subscale of the NEO Personality Inventory (Costa & McCrea, 1985) (Cronbach’s alpha = .835). At six months, mothers completed the Parental Modernity Scale of Child-Rearing and Educational Beliefs (Schaefer & Edgerton, 1985). The 30 items on this sale provide an estimate of how progressive (democratic, child-centered) versus traditional (authoritarian, strict, adult-centered) the parent’s attitudes are toward child rearing and discipline. Sample items include “parents should teach their children that they should be doing something useful at all times” (reflected) “parents should go along with the game when their child is pretending something” and “children have a right to their own point of view and should be allowed to express it.” Responses ranged from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree. Consistent with prior work using this scale (Dowsett, Huston, Imes, & Gennetian, 2008), we combined the items into a single index, which had composite reliabilities above .80 across all timepoints, which assesses the extent to which attitudes are traditional (strict, conservative, authoritarian and parent-centered) rather than child-centered (progressive).

Attachment security.

At 24 months, trained observers visited families’ homes and, after a 2-hour observation period, completed the Attachment Behavior Q-Set (Waters & Deane, 1985). The observer sorted the 90 items (cards) of the Attachment Behavior Q-Set into nine piles ranging from least characteristic to most characteristic of a particular subject. The final sort conformed to asymmetrical, unimodal distribution with specified numbers of items in each of the nine piles. Each item was given a final score in terms of its placement in the distribution. A Pearson correlation variable was then obtained by correlating the child’s sort with a secure criterion sort. Reliability, measured as both the Pearson correlation coefficient (r = .92) and a reliability estimated based on repeated measures ANOVA (= .96), indicated a high degree of reliability for the security measure at 24 months.

Results

We used Mplus Version 6 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012) to estimate each model using full-information maximum-likelihood estimation. Missingness on the outcome variable of maternal sensitivity was almost 27% at the age 11 assessment. Families that dropped out of the study had mothers who were younger (r = .12, p < .001), less educated (r = .13, p < .001), more likely to be Black (r = .06, p = .019), and not have their husband or partner living with them (r = .08, p = .003), and report their child as less securely attached (r = .07, p = .021) and male (r = .07, p = .010). We tested several nested models, and selected the most appropriate on statistical (Hu & Bentler, 1998) and conceptual grounds. The initial model estimated change in maternal sensitivity (both constant linear change as well as occasion-specific changes). In order to increase similarity in length of lags between assessments, phantom variables (Rindskopf, 1984) stand in for maternal sensitivity at two time points when it was not measured (i.e., age 8 and 10). This first model also included all paths that reflected our hypotheses. First, we regressed maternal sensitivity onto mother breastfeeding. Specifically, maternal sensitivity at 6 months was regressed onto breastfeeding status at 6 weeks, change in maternal sensitivity between 6 months and 15 months was regressed onto breastfeeding status at 6 months, and later changes in maternal sensitivity were regressed onto breastfeeding duration. Second, we regressed attachment status at 24 months onto breastfeeding status at 6 weeks and 6 months. Third, we regressed changes in maternal sensitivity after 24 months onto attachment status. Mother neuroticism, parenting attitudes, education, partner living with the mother at 1 month, and mother race were included as additional correlates of initial status and predictors of change in maternal sensitivity.

The next models retained all variables from the initial model, and invoked invariance constraints on the regression weights of parallel paths across time. For example, the regression weight of the path from number of weeks mother breastfed child to mother sensitivity at age 2 was constrained to be equal to the regression weight associated with the path from weeks mother breastfed child to mother sensitivity at all later ages. These constraints did not significantly worsen model fit, Δχ2 = 4.68, Δdf = 7, p = .46, which suggests that the hypothesized associations did not vary across the spans of development covered by this model. The prediction from the two indicators of mother breastfeeding at six weeks and six months were not included in these constraints. Attachment to caregiver was regressed onto breastfeeding status at six weeks and breastfeeding status at six months. These two paths to attachment security could be equated without a loss in model fit, Δχ2 = 0.46, Δdf = 1, p = .76, suggesting that the increase in attachment security between children who were breastfeeding at six months and those who were at six weeks but stopped before six months was equal in magnitude to the increase in attachment security between children who were breastfeeding at six weeks versus children who were not breastfed at six weeks. That is, the link from breastfeeding duration to attachment security was additive (i.e., consistent with a dose-response). As a final step, we set to zero all structural paths that were not statistically significant. Based on the nonsignificant drop in fit for each of these models, this last model was selected as the final and most parsimonious representation of study findings, χ2 = 148.41, df = 54, RMSEA = .037, TLI = .978.

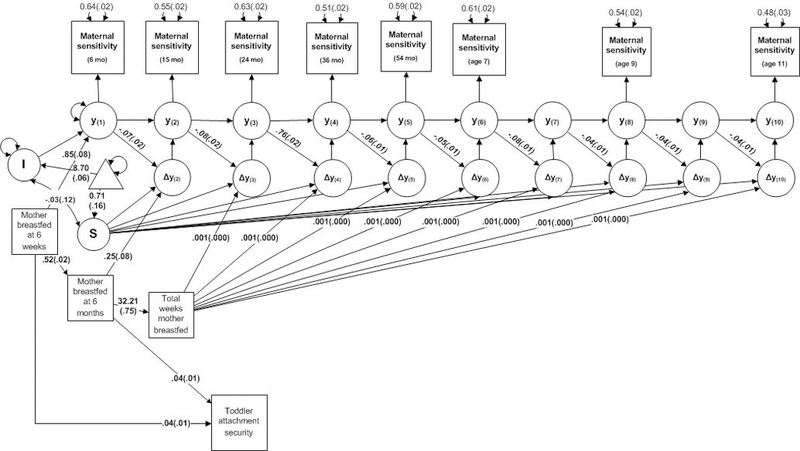

Figure 1 contains the paths and coefficients associated with this final model, with covariates omitted for the sake of clarity. Paths without coefficients are fixed at 1. The initial level of maternal sensitivity was 8.70 (SE = 0.06), and the linear change in maternal sensitivity was an increase of 0.71 units (SE = 0.16). The correlation between initial level and linear change in maternal sensitivity was not significant, r = −.03 (SE = 0.12). Occasion specific changes in maternal sensitivity ranged from −.04 to −.08 with a single exception; a change in the coding of maternal sensitivity at 36 months resulted in a jump in the mean sensitivity rating, b = 0.76 (SE = 0.02). Mothers who reported breastfeeding at 6 weeks were more sensitive during observed interactions at 6 months, b = 0.85 (SE = 0.08). Consistent with the hypothesis that breastfeeding would predict changes in observed maternal sensitivity, the path from breastfeeding status at 6 months to change in maternal sensitivity at 15 months was significant, as were the paths from total weeks mother breastfed to subsequent changes in maternal sensitivity. Breastfeeding status at 6 weeks and 6 months predicted higher attachment security at 24 months. Toddler attachment security did not predict increases in maternal sensitivity net of the other variables in the model. These associations did not vary between males and females.

Figure 1.

Observed maternal sensitivity as predicted from breastfeeding duration, adjusted for demographic covariates. Standard errors are in parentheses. All coefficients significant at α < .05. Paths without a coefficient are fixed to 1.

To test whether this prediction to parenting behavior was unique to mothers, we ran a parallel model predicting father sensitivity from mother breastfeeding. Breastfeeding behavior did not predict changes in father sensitivity.

Discussion

The current study represents the first longitudinal investigation of the potential effects of breastfeeding duration on maternal sensitivity across the following decade. Based upon prior work linking breastfeeding status with maternal behavioral and attentional sensitivity (Kim et al., 2011; Papp, 2013; Pearson et al., 2011), we hypothesized that breastfeeding would predict increases over time in mothers’ parenting behaviors. This hypothesis received support in this sample, in that breastfeeding duration predicted increases in maternal sensitivity, above and beyond family and maternal background characteristics. Further, breastfeeding was observed to have positive consequences for maternal sensitivity beyond the infant/toddler period. Mothers who persisted in breastfeeding for a longer duration increased their maternal sensitivity over time, suggesting that breastfeeding may set in motion a cascade of positive benefits for mothers in their parenting behaviors. The hypothesized positive effect of breastfeeding on maternal sensitivity over time may represent one mechanism through which the observed links between breastfeeding and many adult outcomes may operate (Alati et al., 2009; Golding et al., 1997; Hughes & Bushnell, 1977; Kramer et al., 2008; Schwarze et al., 2014).

In light of the importance that breastfeeding has received in the medical and nursing fields, the comparative lack of attention to breastfeeding in the parenting literature is notable. However, one could argue that breastfeeding is one of the first parenting decisions a couple makes, and better understanding the relational and socioemotional implications this infant feeding practice has for the breastfeeding dyad is critical. Results from the current study substantiate and extend prior work indicating a link between breastfeeding and maternal sensitivity (Britton et al., 2006; Edwards et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2011; Pearson et al., 2011; Tharner et al., 2012) by demonstrating longitudinal associations between breastfeeding duration and subsequent increases in maternal sensitivity over the period from 6 months to 11 years. Importantly, we demonstrate that this association is unique to mothers and that fathers do not show increased sensitivity with their infants as a result of maternal behavior.

We also demonstrate in this study a predictive link between breastfeeding duration and attachment security in toddlerhood. Specifically, we found that the link from breastfeeding duration to attachment security was additive, but we did not find evidence that attachment security subsequently predicted increases in maternal sensitivity. Thus, there was no evidence for attachment as a mediator between breastfeeding duration and sensitivity in this study. Although findings from research on breastfeeding and attachment security have been mixed, the current results are consistent with the idea that the close, consistent interaction provided by breastfeeding may be one avenue through which attachment security is strengthened in the mother-child pair. These findings are similar to those reported by Tharner and colleagues (2012) in their sample of mothers and babies up to 14 months of age, but we demonstrate the link between breastfeeding and attachment security at temporally distinct timepoints.

In addition to demonstrating predictive associations between breastfeeding duration and changes in maternal sensitivity, we also demonstrate that the predicted associations remain after more rigorous causal tests (i.e., accounting for important covariates and predicting to change over time). Many authors have criticized the breastfeeding literature for failing to address the possible role of selection effects (Edwards et al., 2015; Papp, 2013). Although it is not feasible to experimentally manipulate breastfeeding duration, research must address concerns about selection to be compelling. Therefore, we predicted change over time, allowing each mother to serve as her own control (Rosnow & Rosenthal, 2008). We also included factors highlighted in the literature as important to the study of breastfeeding, including maternal education, race/ethnicity, and whether a partner was present in the home. We also included variables that may differentiate breastfeeding mothers, such as neuroticism and parenting attitudes. The take-away message is that breastfeeding duration continues to predict long-term changes in maternal sensitive caregiving after accounting for these differences between families.

The direct effects observed in this study were small, which aligns with the theoretical position that breastfeeding behavior is just one of many factors which influence the development of positive mother-child bonds (Else-Quest, Hyde, & Clark, 2003). The small effect sizes observed in this study suggest that breastfeeding duration may continue to have positive benefits at different points during later childhood. Clearly, the mother-child relationship develops in complex ecologies and is multiply determined. However, improving our understanding role of breastfeeding in relationship contexts is important, and the present findings encourage additional consideration of breastfeeding in family-process models of child development.

We were limited in this investigation by a lack of physiological data from mothers, a key consideration in understanding the mechanisms through which breastfeeding may promote maternal sensitivity. Several studies indicate that stimulation of the nipple during breastfeeding promote oxytocin and prolactin release, hormones tied to caregiving behaviors in the mother (Feldman, Weller, Zagoory-Sharon, & Levine, 2007; Mann & Bridges, 2001; Moberg & Prime, 2013). Additional research is needed to determine whether oxytocin and associated hormone release is a mechanism through which maternal sensitivity is promoted among breastfeeding mothers.

Three other limitations are also important to note in the current investigation. First, although the sample includes a range of income and educational levels, mothers were not selected based upon clinical or other risk factors (NICHD ECCRN, 2005). Studies based on families facing higher risks than those in this sample have found that breastfeeding protected young children from psychosocial stress experienced due to parental divorce and separation (Montgomery, Ehlin, & Sacker, 2006) and that breastfeeding duration was an inverse predictor of maternal neglect over the course of 15 years (Strathearn, Mamun, Najman, & O’Callaghan, 2009). In light of this research, it seems even more imperative to continue investigating the socioemotional benefits of breastfeeding for mothers and infants.

Second, we lacked information in the current sample about whether mothers were exclusively breastfeeding or mixed feeding their infants. As some research suggests that the benefits of breastfeeding might be more pronounced for exclusively breastfeeding mothers (Edwards et al., 2015), it would seem worthwhile in future investigations to include more fine-grained measures of the level of exclusivity in breastfeeding and the exact mode of feeding (feeding breastmilk with a bottle, formula feeding, mixed feeding, etc.). Ultimately, generating a more specific understanding of how breastfeeding impacts the mother-infant dyad will facilitate best practices for supporting breastfeeding in early childhood and family relationship contexts.

Third, the mothers who remained in the study through the early adolescent assessment at age 11 were different from mothers who dropped out of the study on several variables included in this model, including observed sensitivity. Consequently, this data cannot be considered as missing at random, and subsequent parameter estimates may not generalize to the full SECCYD sample.

Contributor Information

Jennifer M. Weaver, Department of Psychological Science, Boise State University

Thomas J. Schofield, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Iowa State University

Lauren M. Papp, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison

References

- Ainsworth MDS, Bell SM, & Stayton DJ (1974). Infant-mother attachment and social development: Socialisation as a product of reciprocal responsiveness to signals In Richards MPM (Ed.), The integration of a child into a social world (pp. 99–135). New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Akman İ, Kuscu MK, Yurdakul Z, Özdemir N, Solakoğlu M, Orhon L, Karabekiroglu, & Özek E. (2008). Breastfeeding duration and postpartum psychological adjustment: role of maternal attachment styles. Journal of paediatrics and child health, 44(6), 369–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anisfield E, Casper V, Nozyce M, & Cunningham N (1990). Does infant carrying promote attachment? An experimental study of the effects of increased physical contact on the development of attachment. Child Development, 61, 1617–1627. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02888.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alati R, Van Dooren K, Najman JM, Williams GM, & Clavarino A (2009). Early weaning and alcohol disorders in offspring: Biological effect, mediating factors or residual confounding? Addiction, 104, 1324–1332. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02643.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow AE, Power M, Gillis DE, Maclellan-Peters J, Alex M, & McDonald C (2014). Breastfeeding, skin-to-skin contact, and mother-infant interactions over infants’ first three months. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35, 51–62. 10.1002/imhj.21424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky Jay & Pasco Fearon RM (2002) Early attachment security, subsequent maternal sensitivity, and later child development: Does continuity in development depend upon continuity of caregiving?, Attachment & Human Development, 4, 361–387. 10.1080/14616730210167267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1 Attachment. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Britton JR, Britton HL, & Gronwaldt V. (2006). Breastfeeding, sensitivity and attachment. Pediatrics, 118, 1436–1443. 10.1542/peds.2005-2916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A (2014). Maternal trait personality and breastfeeding duration: The importance of confidence and social support. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70, 587–598. 10.1111/jan.12219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A., & Arnott B (2014). Breastfeeding duration and early parenting behaviour: The importance of an infant-led, responsive style. PLOS ONE 9: e83893. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciciolla L, Crnic KA, & West SG (2013). Determinants of change in maternal sensitivity: Contributions of context, temperament, and developmental risk. Parenting, 13(3), 178–195. 10.1080/15295192.2013.756354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa P, & McCrae R (1985). The NEO Personality Inventory Manual. Odessa, Fl: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- de Wolff MS, & van IJzendoorn MH (1997). Sensitivity and attachment: A meta-analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child Development, 68, 571–591. 10.2307/1132107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowsett CJ, Huston AC, Imes AE, & Gennetian L (2008). Structural and process features in three types of child care for children from high and low income families. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23, 69–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RC, Thullen MJ, Henson LG, Lee H, & Hans SL (2015). The association of breastfeeding initiation with sensitivity, cognitive stimulation, and efficacy among young mothers: A propensity score matching approach. Breastfeeding Medicine, 10, 13–19. 10.1089/bfm.2014.0123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eidelman AI, & Schanler RJ (2012). Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 129, e827–e841. 10.1542/peds.2011-3552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest NM, Hyde JS, & Clark R (2003). Breastfeeding, bonding, and the mother-infant relationship. Merill-Palmer Quarterly, 49, 495–517. 10.1353/mpq.2003.0020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman F, Weller A, Zagoory-Sharon O, & Levine A (2007). Evidence for a neuroendocrinological foundation of human affiliation: plasma oxytocin levels across pregnancy and the postpartum period predict mother-infant bonding. Psychological Science, 18, 965–970. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02010.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Davis CM, & Brooks-Gunn J (2007). The association of couples’ relationship status and quality with breastfeeding initiation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 1107–1117. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00435.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey JR & Lawrence RA (2010). Toward optimal health: the maternal benefits of breastfeeding. Journal of Women’s Health, 19, 1597–1602. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding J, Rogers IS, & Emmett PM (1997). Association between breast feeding, child development and behavior. Early Human Development, 49, S175–S184. 10.1016/S0378-3782(97)00062-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn-Holbrook J, Haselton MG, Schetter CD, & Glynn LM (2013). Does breastfeeding offer protection against maternal depressive symptomatology? Archives of women’s mental health, 16(5), 411–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott P, Tappin D, & Wright C (2008). Breast feeding. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 336, 881–887. 10.1136/bmj.39521.566296.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes RN, & Bushnell JA (1977). Further relationships between IPAT Anxiety Scale performance and infantile feeding experiences. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 33, 698–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen J, de Weerth C, & Riksen-Walraven JM (2008). Breastfeeding and the mother-infant relationship – A review. Developmental Review, 28, 503–521. 10.106/j.dr.2008.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K (2013). Maternal-Infant bonding: A review of the literature. International Journal of Childbirth Education, 28, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kim P, Feldman R, Mayes LC, Eicher V, Thompson N, Leckman JF, & Swain JE (2011). Breastfeeding, brain activation to own infant cry, and maternal sensitivity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 907–915. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02406.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MS, Aboud F, Mironova E, Vanilovich I, Platt RW, Matush L, et al. (2008). Breastfeeding and child cognitive development: New evidence from a large randomized trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65, 578–584. 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzela AL, Stifter CA, & Worobey J (1990). Breastfeeding and mother-infant interactions. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 8, 185–194. 10.1080/02646839008403623 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, Weaver JM, & O’Brien M (2012). Differentiating maternal sensitivity to infant distress and non-distress. Parenting: Science and Practice, 12, 175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann PE, & Bridges RS (2001). Lactogenic hormone regulation of maternal behavior. Progressive Brain Research, 133, 251–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzacappa ES & Katkin ES (2002) Breast-feeding is associated with reduced perceived stress and negative mood in mothers. Health Psychology, 21, 187–193. 10.1037//0278-6133.21.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberg KU, & Prime DK (2013). Oxytocin effects in mothers and infants during breastfeeding. Infant, 9, 201–206. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SM, Ehlin A, & Sacker A (2006). Breast feeding and resilience against psychosocial stress. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 91, 990–994. 10.1136/adc.2006.096826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2012). Mplus User’s Guide, 6th ed Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD ECCRN (1999). Child care and mother-child interaction in the first 3 years of life. Developmental Psychology, 35, 1399–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD ECCRN (2003). Early child care and mother–child interaction from 36 months through first grade. Infant Behavior and Development, 26, 345–370. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD ECCRN (2005). Child care and child development: Results from the NICHD study of early child care and youth development. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oddy WH, Robinson M, Kendall GE, Li J, Zubrick SR, & Stanley FJ (2011). Breastfeeding and early child development: A prospective cohort study. Acta Paediatrica, 100, 992–999. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02199.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen MT, Klausli JK, & Murrey M (2000). The NICHD Study of Early Child Care Parent-Child Interaction Scales: Middle Childhood. University of Texas at Dallas; Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Owen MT, Vaughn A, Barfoot B, & Ware A (1996). The NICHD Study of Early Child Care Parent- Child Interaction Scales: Early Childhood. University of Texas at Dallas; Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Papp LM (2013). Longitudinal associations between breastfeeding and observed mother-child interaction qualities in early childhood. Child: Care, Health and Development, 40, 740–746. 10.1111/cch.12106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson RM, Lightman SL, & Evans J (2011). The impact of breastfeeding on mothers’ attentional sensitivity towards infant distress. Infant Behavior & Development, 34, 200–205. 10.106/j.infbeh.2010.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PJ, O’Callaghan M, Williams GM, Najman JM, Andersen MJ, & Bor W (2001). The effect of breastfeeding on child development at 5 years: A cohort study. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 37, 465–469. 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2001.00702.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindskopf D (1984). Using phantom and imaginary latent variables to parameterize constraints in linear structural models. Psychometrika, 49, 37–47. 10.1007/BF02294204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosnow RL, & Rosenthal R (2008). Assessing the effect size of outcome research In Nezu AM, & Nezu CM (Eds.). (2007). Evidence-based outcome research: A practical guide to conducting randomized controlled trials for psychosocial interventions (pp. 379–401). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan AS, Wenjun Z, & Acosta A (2002). Breastfeeding continues to increase into the new millennium. Pediatrics, 110(6), 1103–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer E, & Edgarton M (1985). Parental and child correlates of parental modernity In Sigel IE (Ed.), Parental belief systems: The psychological consequences for children (pp. 287–318). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze PA, & Carlisle SA (2010). What research does and doesn’t say about breastfeeding: A critical review. Early Child Development and Care, 180, 703–718. 10.1080/03004430802263870 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarze CE, Hellhammer DH, Stroehle V, Lieb K, & Mobascher A (2014). Lack of breastfeeding: A potential risk factor in the multifactorial genesis of borderline personality disorder and impaired maternal bonding. Journal of Personality Disorders, 28, 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan S, Stewart M, & Dunne L (2010). The effect of breastfeeding and stimulation in the home on cognitive development in one-year-old infants. Child Care in Practice, 16, 101–110. 10.1080/13575270903529136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JP, & Forrester R (2017). Maternal time use and nurturing: Analysis of the association between breastfeeding practice and time spent interacting with baby. Breastfeeding Medicine. Advance online publication. 10.1089/bfm.2016.0118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JP, & Ellwood M (2011). Feeding patterns and emotional care in breastfed infants. Social Indicators Research, 101, 227–231. 10.1007/s11205-010-9657-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strathearn L, Mamun AA, Najman JM, & O’Callaghan MJ (2009). Does breastfeeding protect against substantiated child abuse and neglect? A 15-year cohort study. Pediatrics, 123, 483–493. 10.1542/peds.2007-3546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturge-Apple ML, Davies PT, Boker SM, & Cummings EM (2004). Interparental discord and parenting: Testing the moderating roles of child and parent gender. Parenting: Science and Practice, 4, 361–380. 10.1207/s15327922par0404_7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tharner A, Luijk MPCM, Raat H, Ijzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Moll HA, & Tiemeier H (2012). Breastfeeding and its relation to maternal sensitivity and infant attachment. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 33, 396–404. 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318257fac3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thulier D, & Mercer J (2009). Variables associated with breastfeeding duration. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 38, 259–268. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01021.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Health and Human Services (2011). The Surgeon General’s call to action to support breastfeeding. Retrieved from http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/calls/breastfeeding/calltoactiontosupportbreastfeeding.pdf

- Waters E, & Deane K (1985). Defining and assessing individual differences in attachment relationships: Q-methodology and the organization of behavior in infancy and early childhood In Bretherton I & Waters E (Eds.), Growing points of attachment theory and research (pp. 41–65). Chicago: Monographs for the Society for Research in Child Development. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox RR (2005). Introduction to robust estimation and hypothesis testing. New York, NY: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthou M (1998). Immune protection of human milk. Biology of the Neonate, 74, 121–133. 10.1159/000014018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]