Abstract

Background

Predicting which patients with hip osteoarthritis are more likely to show disease progression is important for healthcare professionals. Therefore, the aim of this review was to assess which factors are predictive of progression in patients with hip osteoarthritis.

Methods

A literature search was made up until 14 March 2019. Included were cohort and case-control studies evaluating the association between factors and progression (either clinical, radiological, or THR). Excluded were studies with a follow-up < 1 year or specific underlying pathologies of osteoarthritis. Risk of bias was assessed using the QUIPS tool. A best-evidence synthesis was conducted.

Results

We included 57 articles describing 154 different factors. Of these, a best-evidence synthesis was possible for 103 factors, separately for clinical and radiological progression, and progression to total hip replacement. We found strong evidence for more clinical progression in patients with comorbidity and more progression to total hip replacement for a higher Kellgren and Lawrence grade, superior or (supero) lateral femoral head migration, and subchondral sclerosis. Strong evidence for no association was found regarding clinical progression for gender, social support, pain medication, quality of life, and limited range of motion of internal rotation or external rotation. Also, strong evidence for no association was found regarding radiological progression for the markers CTX-I, COMP, NTX-I, PINP, and PIIINP and regarding progression to total hip replacement for body mass index.

Conclusion

Strong evidence suggested that 4 factors were predictive of progression of hip osteoarthritis, whereas 12 factors were not predictive of progression. Evidence for most of the reported factors was either limited or conflicting.

Protocol registration

PROSPERO, CRD42015010757

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13075-019-1969-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Hip, Prognostic factors, Progression, Systematic review

Background

The hip is the third joint most commonly affected by osteoarthritis (OA) [1]. No therapeutic cure exists for hip OA. Therefore, predicting which patients with hip OA are more likely to progress in their disease is of special interest, particularly if these predictive factors are potentially modifiable.

In 2002, Lievense et al. published a systematic review in which they identified several predictive factors for the progression of hip OA [2]. They used a best-evidence synthesis to draw conclusions about the available evidence per factor. Strong evidence was found for more rapid progression in patients with a superior or superolateral migration of the femoral head or an atrophic bone response. Conversely, strong evidence was found for no association between progression of hip OA and obesity. In 2009, Wright et al. also reviewed the known prognostic factors and their quality of evidence [3]. They concluded that only a few factors are strongly associated with the progression of hip OA, i.e., age, joint space width, migration of the femoral head, femoral osteophytes, bony sclerosis, Kellgren and Lawrence (K-L) grade 3, hip pain at baseline, and a Lequesne index score > 10. In that review, acetabular osteophytes showed no association with progression. Furthermore, de Rooij et al. studied the factors predicting the course of pain and function. They found strong evidence that higher comorbidity count and lower vitality predict a worsening of physical function [4]. Although all reviews described additional predictive factors, the evidence for these factors was either limited or conflicting.

Since the literature search of Wright et al. (in October 2008) and de Rooij et al. (in July 2015) more research on prognostic factors of hip OA have been conducted, and new methods to assess and review prognostic studies have been developed [5].

Therefore, the aim of this present study was to systematically review the evidence of patient, health, and diagnostic variables associated with the progression of hip OA.

Methods

Search of the literature

A search was made in the databases of Embase, MEDLINE (OvidSP), Web-of-Science, Cochrane Library, PubMed publisher, and Google Scholar from the inception of the database until 14 March 2019, using the keywords hip, osteoarthritis, and prognosis (and their synonyms). We excluded congress abstracts and editorial letters from our search by setting these as limits to restrain the number of found citations without losing valuable citations. The reference lists of relevant articles were screened for additional relevant studies. A complete syntax of the search can be found in Additional file 1. The process of the search was assisted and partly conducted by an experienced medical librarian.

Criteria for selection of studies

The following are the criteria for the selection of studies:

The study should investigate the factors associated with the progression of hip OA.

The article was written in English, Dutch, German, French, Spanish, Italian, Danish, Norwegian, or Swedish. These languages were sufficiently mastered by at least two reviewers.

The article was available in full text.

Patients in the study reported complaints like pain, disability, or stiffness of the hip, suspected or confirmed (radiographic or clinical criteria) to originate from OA of the hip.

The study design was a cohort or a case-control study or a randomized controlled trial in which the estimation of the prognostic factor was adjusted for the intervention or only investigated in the control group.

Progression was determined radiographically or clinically. Radiographic progression could be determined by, for example, X-ray or MRI. Examples of clinical progression were worsening of pain or function or reaching the point of indication for total hip replacement (THR).

Follow-up should be at least 1 year (based on the recommendations for measuring structural progression [6]).

The study was excluded if the population under investigation had a specific underlying pathology, such as trauma (fractures), infection, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Perthes’ disease, tuberculosis, hemochromatosis, sickle cell disease, Cushing’s syndrome, and femoral head necrosis.

Selection of studies

CHT screened all the titles and abstracts and excluded articles that did not investigate patients with OA of the hip. Secondly, CHT and PAJL independently selected the titles and abstracts using the selection criteria to decide which articles required the retrieval of full text; in case of disagreement, the full text was retrieved. Then, all full texts were independently assessed by CHT and PAJL to include all relevant studies according to the selection criteria. In case of disagreement and both reviewers were unable to reach consensus, SMABZ made the final decision.

Data extraction

Information on the design, setting, study population (e.g., recruitment period, age, gender, definition of hip OA), number of participants, follow-up period, loss to follow-up, prognostic factors, assessment of progression, outcomes, and strength of association were extracted using standardized forms by CHT and checked by PAJL.

Prognostic factors were divided into patient variables, disease characteristics, and chemical or imaging markers. Outcomes were divided into clinical progression, radiographic progression, or (indication for) receiving a THR.

If outcomes were measured at several follow-up moments, all moments were extracted. After the collection of all data, the follow-up moments that were in the closest range to each other were used for the evidence synthesis.

Risk of bias assessment

The quality of all included cohort studies was evaluated using the QUIPS tool [5, 7]. Studies were assessed on six domains: study participation, study attrition, prognostic factor measurement, outcome measurement, study confounding, and statistical analysis and reporting. An overview of all domains and their items is presented in Additional file 2. Each study was independently scored by CHT and by a second reviewer (DMJD, SMABZ, PKB, JBMRO, or PAJL). In case of disagreement, they attempted to reach consensus; if this failed, a third reviewer (JBMRO or PAJL) made the final decision.

Evidence synthesis

A meta-analysis was considered if clinical heterogeneity was low, with respect to the study population, the risk of bias, and the definition of prognostic factors and defined hip OA progression. In case of a meta-analysis, an adjusted GRADE assessment for prognostic research was used to determine the strength of the evidence [8].

If the level of heterogeneity of the studies was high, we refrained from pooling in the main analysis and performed a qualitative evidence synthesis. Associations were categorized as positive, negative, or no association. Ranking of the levels of evidence was based on Lievense et al. [2] and Davis et al. [9]:

Strong evidence: consistent findings (≥ 75% of the studies showing the same direction of the association) in two or more studies with a low risk of bias in all domains of the QUIPS tool

Moderate evidence: consistent findings in more than two studies with a moderate or high risk of bias in one or more domains of the QUIPS tool or consistent findings in two studies, of which one study has a low risk of bias in all domains of the QUIPS tool

Limited evidence: one study with a low risk of bias in all domains of the QUIPS tool or two studies with a moderate or high risk of bias in one or more domains of the QUIPS tool

Conflicting evidence: < 75% of the studies showing the same direction of the association

If a prognostic factor was described in two different articles that investigated the same study cohort and outcome of progression, one study was selected to include in the evidence synthesis. In this case, we selected the article according to a decision tree: (1) lowest risk of bias, (2) prognostic factor is the primary outcome of the study, and (3) the largest number of participants.

Post hoc changes to the study protocol

After contact with one of the developers of the QUIPS tool, we learned that it is not validated to judge the risk of bias of case-control studies and would probably not adequately take into account the higher risk of recall bias and the selection bias of case-control studies. Therefore, we decided to exclude case-control studies from our evidence synthesis, except for nested case-control studies. Nested case-control studies are less prone to selection and recall bias because of the underlying known cohort [10], which can be judged using the QUIPS tool.

Results

Included studies

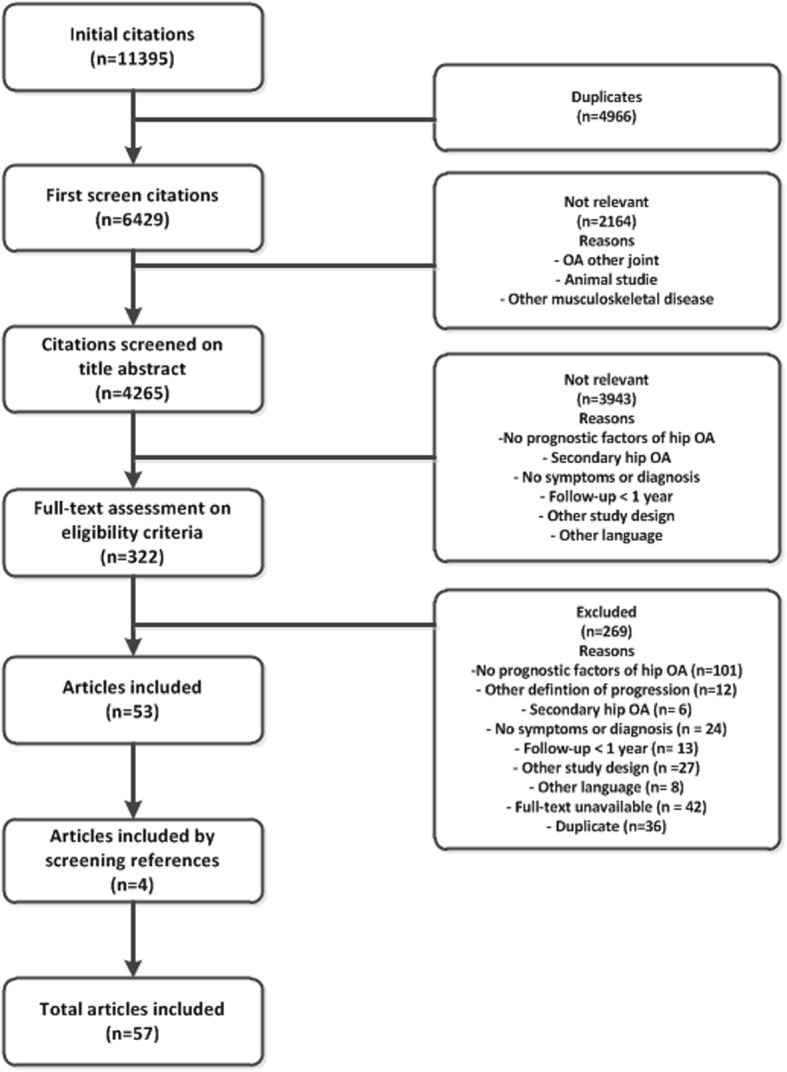

The initial search yielded 6429 citations of which 57 articles were finally included. Figure 1 shows the reasons for the study exclusion, and Table 1 presents a brief overview of the characteristics of the 57 included studies (a more extensive overview is available in Additional file 3). Of the 57 studies, 48 were cohort studies (37 with a prospective design), 4 were nested case-control studies, and 5 were case-control studies. These last 5 studies were excluded from the evidence synthesis for the reasons mentioned above.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the search and selection of studies

Table 1.

Characteristics of the selected studies

| Study | Design | Participants in the cohort (n) | Assessment of progression | Follow-up period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricola et al. [11] | Prospective cohort (CHECK) | 1002 (analyzed 723 patients) | THR | 5 years |

| Agricola et al. [12] | Prospective cohort (CHECK) | 1002 (analyzed 550 women) | THR due to OA | 5 years |

| Agricola et al. [12] | Nested case-control (Chingford cohort) | 1003 (analyzed 114) | THR due to OA | 19 years |

| Auquier et al. [13] | Retrospective cohort | 131 | Increase in stage of pain and function, stages minimal, moderate, moderate-severe, severe | 6–23 years |

| Barr et al. [14] | Case-control | 195 (analyzed 102 patients) | THR (compared to non-progression hips: increase of ≤ 1 K-L grade) | 5 years |

| Bastick et al. [15] | Prospective cohort (CHECK) | 545 (analyzed 363 patients) | NRS score for pain, group moderate progression compared to mild pain. Groups based on LCGA | 5 years |

| Bastick et al. [16] | Prospective cohort (CHECK) | 588 (analyzed 538) | THR | 5 years |

| Bergink et al. [17] | Prospective cohort (Rotterdam I) | 176 |

1. Increase ≥ 1 K-L grade 2. Decrease ≥ 1 mm of joint space |

Average 8.4 years |

| Birn et al. [18] | Case-control | 94 (5 cases, 89 controls) | Rapidly destructive OA: > 2 mm or > 50% JSN/year | NR |

| Birrell et al. [19] | Prospective cohort | 195 | Time to being put on a waiting list for THR | 36 months |

| Bouyer et al. [20] | Prospective cohort (KHOALA) | 242 (analyzed 133 patients) |

1. Increase ≥ 1 K-L grade 2. Increase ≥ 1 JSN score 3. Time to THR |

3 years |

| Castano Betancourt et al. [21] | Prospective cohort (GOAL) | 189 | JSN ≥ 20% compared to baseline or THR | 2 years |

| Chaganti et al. [22] | Nested case-control (SOF) | 168 cases and 173 controls | Decrease in MJS of 0.5 mm, increase of ≥ 1 in summary grade, increase ≥ 2 in total osteophyte score, or THR for OA | Average 8.3 years |

| Chevalier et al. [23] | Prospective cohort | 30 | Rapid evolution: JSN > 0.6 mm/year | 1 year |

| Conrozier et al. [24] | Case-control | 104 (analyzed 10 cases, 23 controls) | Rapidly progressive hip OA: severe hip pain, symptom onset within the last 2 years, annual rate of JSN > 1 mm, ESR < 20 mm/h, absence of detectable inflammatory or crystal-induced joint disease | NR |

| Conrozier et al. [25] | Retrospective cohort | 89 | Radiographic: YMN, calculated from MJS in mm/year | 18–300 months |

| Conrozier et al. [26] | Prospective cohort | 48 | JSN in mm/year | 1 year |

| Danielsson [27, 28] | Prospective cohort | 168 |

1. Increase in pain index 0–5 2. Operation because of hip OA 3. Increase in radiographic index 0–10 |

8–12 years |

| van Dijk et al. [29] | Prospective cohort | 123 |

1. Decrease in WOMAC function 2. Increase in seconds of timed walking test |

3 years |

| van Dijk et al. [30] | Prospective cohort | 123 |

1. Decrease in WOMAC function 2. Increase in seconds of timed walking test |

3 years |

| Dorleijn et al. [31] | Prospective cohort (GOAL) | 222 (analyzed 111 patients) | VAS score for pain, group highly progressive compared to mild pain groups based on LCGA | 2 years |

| Dougados et al. [32] | Prospective cohort (ECHODIAH) | 508 (analyzed 461 patients) | Radiological: ≥ 0.6 mm decrease in JSW | 1 year |

| Dougados et al. [33] | Prospective cohort (ECHODIAH) | 508 (analyzed 463 patients) | Radiological: > 0.5 mm decrease in JSW | 2 years |

| Dougados et al. [34] | Prospective cohort | 508 | Time to the requirement of THR | 3 years |

| Fukushima et al. [35] | Prospective cohort | 20 | Increase in Tönnis grade | 25 months |

| Golightly et al. [36] | Prospective cohort (Johnston County) | 1453 | Increase in K-L grade or increase in hip symptoms (mild, moderate, severe) | 3–13 years |

| Gossec et al. [37] | Prospective cohort | 741 (analyzed 505 patients) | THR | 2 years |

| Hartofilakidis et al. [38] | Retrospective cohort | 210 | THR | 2 to > 10 years |

| Hawker et al. [39] | Prospective cohort | 2128 | Time to THR | 6.1 years |

| Hoeven et al. [40] | Prospective cohort (Rotterdam I) | 5650 (number analyzed: NR) | Increase ≥ 1 K-L grade baseline to follow-up | 10 years |

| Holla et al. [41] | Prospective cohort (CHECK) | 588 | Moving into a higher group (quintiles of WOMAC-PF 0–68) or remaining within the three highest groups | 2 years |

| Juhakoski et al. [42] | Prospective cohort | 118 |

1. WOMAC pain (0–100) 2. WOMAC function (0–100) |

2 years |

| Kalyoncu et al. [43] | Retrolective cohort (ECHODIAH) | 192 | THR | 10 years |

| Kelman et al. [44] | Nested case-control (SOF) | 396 (cases 197, controls 199) | Decrease in minimum joint space of ≥ 0.5 mm, an increase of ≥ 1 in the summary grade, an increase of ≥ 2 in total osteophyte score, or THR | 8.3 years |

| Kerkhof et al. [45] | Prospective cohort (Rotterdam I) | 1610 | Radiologic: JSN ≤ 1.0 mm or THR during follow-up | NR |

| Kopec et al. [46] | Prospective cohort (Johnston County) | 1590 (analyzed 571 people) | Increase ≥ 1 in K-L grade | 3–13 years |

| Lane et al. [47] | Prospective cohort (SOF) | 745 | Decrease in minimum joint space of ≥ 0.5 mm, an increase of ≥ 1 in the summary grade, an increase of ≥ 2 in total osteophyte score, or THR | 8 years |

| Lane et al. [48] | Nested case-control (SOF) | 342 | Radiological: decrease in minimum joint space of ≥ 0.5 mm, an increase of ≥ 1 in the summary grade, an increase of ≥ 2 in total osteophyte score, or THR | 8.3 years |

| Laslett et al. [49] | Prospective cohort (TasOAC) | 1099 (analyzed 765 people) | WOMAC pain (0–100) | 2–4 years |

| Ledingham 1993 [50] | Prospective cohort | 136 |

1. Global assessment of radiographic change 2. THR |

3–73 months |

| Lievense et al. [51] | Prospective cohort | 224 (analyzed 163 patients) | THR | 5.8 years |

| Maillefert et al. [52] | Prospective cohort (ECHODIAH) | 508 |

1. Decrease in JSW > 50% during the first year follow-up 2. THR in 1–5 years of follow-up |

5 years |

| Mazieres et al. [53] | Prospective cohort (ECHODIAH) | 507 (analyzed 333 patients) | JSN ≥ 0.5 mm or THP | 3 years |

| Nelson et al. [54] | Prospective cohort (Johnston County) | 309 |

1. Increase in K-L grade 2. Increase in osteophyte severity grade 3. Increase in JSN severity grade |

5 years |

| Perry et al. [55] | Case-control | 44 | Radiographic: progressive deterioration | 5–14 years |

| Peters et al. [56] | Prospective cohort | 587 (analyzed 214 patients) | New Zealand score 0–80 (combination of pain and function) | 7 years |

| Pisters et al. [57] | Prospective cohort | 149 | Increase in WOMAC function on average over time (measured at 1, 2, 3, 5 years) | 5 years |

| Pollard 201et al. 2 [58] | Prospective cohort | 264 | Signs on examination of hip OA or symptoms at baseline and signs and symptoms at follow-up | 5 years |

| Reijman et al. [59] | Prospective cohort (Rotterdam I) | 1235 | JSN ≥ 1.0 mm in at least 1 of 3 compartments (lateral, superior, axial) | 6.6 years |

| Reijman et al. [60] | Prospective cohort (Rotterdam I) | 1904 | Radiologic: JSN ≤ 1.0 mm or THR during follow-up | 6.6 years |

| Reijman et al. [61] | Prospective cohort (Rotterdam I) | 1676 |

1. JSN of ≥ 1 mm 2. JSN of ≥ 1.5 mm 3. Increase of ≥ 1 K-L grade |

6.6 years |

| Solignac [62] | Prospective cohort (ECHODIAH) | 507 (analyzed 333 patients) | JSN ≥ 0.5 mm or THP | 3 years |

| van Spil et al. [63] | Prospective cohort (CHECK) | 1002 (analyzed 178 patients) | Radiographic: ≥ 1 K-L grade increase | 5 years |

| Thompson et al. [64] | Case-control | 34 cases, controls: NR | Rapidly progressive OA: loss of bone or a combined loss of bone and articular cartilage at rate > 5 mm per year | 18 months |

| Tron et al. [65] | Retrospective cohort | 39 | Mean annual JSN in mm | NR |

| Verkleij et al. [66] | Prospective cohort (GOAL) | 222 (analyzed 111 patients) | VAS score for pain, group highly progressive compared to mild pain, groups based on LCGA | 2 years |

| Vinciguerra et al. [67] | Retrospective cohort | 149 | Time to THR | Variable |

NR not reported, OA osteoarthritis THR total hip replacement, K-L grade Kellgren and Lawrence grade, MJS minimum joint space, JSN joint space narrowing, JSW joint space width, YMN yearly mean narrowing, LCGA latent class growth analysis, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, NRS numeric rating scale, VAS visual analog scale

Risk of bias assessment

In 68% of all assessed domains from all studies, there was an immediate consensus between the reviewers (Cohen’s kappa 0.375, linear weighted kappa 0.484). In 9 assessments of a domain (3%) in 6 different studies, a third reviewer made the final judgment. In total, 15 studies scored a low risk of bias in all domains [15, 16, 21, 29, 30, 32, 34, 37, 41, 44, 47, 49, 53, 57, 63] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment summary (QUIPS)

| Study | Study participation | Study attrition | Prognostic factor measurement | Outcome measurement | Study confounding | Statistical analysis and reporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricola et al. [11] | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low |

| Agricola et al. [12] | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Low |

| Auquier et al. [13] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Bastick et al. [15] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Bastick et al. [16] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Bergink et al. [17] | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Bouyer et al. [20] | Low | High | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Birrell et al. [19] | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low |

| Castano Betancourt et al. [21] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Chaganti et al. [22] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low |

| Chevalier et al. [23] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Conrozier et al. [25] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Conrozier et al. [26] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Danielsson [27, 28] | Low | High | High | High | High | High |

| van Dijk et al. [29] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| van Dijk et al. [30] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Dorleijn 2015 [31] | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Low |

| Dougados et al. [32] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Dougados et al. [33] | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Dougados et al. [34] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Fukushima et al. [35] | Moderate | Low | Low | High | High | Low |

| Golightly et al. [36] | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Gossec et al. [37] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Hartofilakidis et al. [38] | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | High | High |

| Hawker et al. [39] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Hoeven et a. [40] | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Holla et al. [41] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Juhakoski et al. [42] | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Kalyoncu et al. [43] | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Kelman et al. [44] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Kerkhof et al. [45] | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low |

| Kopec et al. [46] | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Lane et al. [47] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Lane et al. [48] | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low |

| Laslett et al. [49] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Ledingham et al. [50] | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | High | High | High |

| Lievense et al. [51] | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low |

| Maillefert et al. [52] | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Mazieres et al. [53] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Nelson et al. [54] | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Peters et al. [56] | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Low |

| Pisters et al. [57] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Pollard et al. [58] | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Reijman et al. [59] | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Reijman et al. [60] | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Reijman et al. [61] | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Solignac [62] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low |

| van Spil et al. [63] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Tron et al. [65] | High | High | High | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Verkleij et al. [66] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low |

| Vinciguerra et al. [67] | Low | Moderate | High | Low | High | High |

Studies with a low risk of bias in all domains are presented in italics

Prognostic factors

We identified 154 possible prognostic factors: 23 patient variables, 77 disease characteristics, and 54 chemical markers or imaging markers. Fifty-one factors were only investigated once in a single cohort or study (not a low risk of bias study) and could not be included in the evidence synthesis. An overview of all the results and risk of bias assessment of the studies describing these factors is presented in Additional file 4. The remaining 103 factors were included in the evidence synthesis. To decrease heterogeneity, evidence synthesis was done separately per group of outcomes (radiological progression, clinical progression, or THR). However, heterogeneity was still considered high in each outcome group, mainly within respect to the definition of the prognostic factor, progression, and measure of the association. Therefore, we refrained from pooling and performed a best-evidence synthesis. If a factor could not be subdivided because it was described by two or three studies that used a definition of progression, all in a separate group of outcome, we combined the groups of outcomes. The results of these factors are presented in Additional file 5.

Evidence for factors predicting progression

Strong evidence was found for a higher K-L grade at baseline, superior or (supero) lateral femoral head migration, and subchondral sclerosis to be predictive of faster progression to THR or more patients progressing to THR. Body mass index was found not to be predictive of faster or more progression to THR (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors predicting (indication for) total hip replacement (THR)

| Prognostic factor | Studies | Associations | Best-evidence synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient variables | |||

| No association | |||

| Body mass index | Strong evidence for no association | ||

|

No, no No, no, no, negative, positive |

|||

| Female | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

No, positive, no No, no, no, no, no |

|||

| Lower educational level | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [16] 1 cohort [39] |

No No |

||

| Western or White ethnicity | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [16] 1 cohort [39] |

No No |

||

| Alcohol consumption | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [16] | No | ||

| Conflicting evidence | |||

| Higher age at baseline | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

No, positive,no No, positive$, no, no, positive |

|||

| Disease characteristics | |||

| Faster or more progression | |||

| Lower global assessment (self-reported) at baseline | Moderate evidence for faster or more progression | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [37] |

Positive Positive, positive |

||

| Previous use of NSAIDs | Limited evidence for more progression | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [37] | Positive | ||

| No association | |||

| Longer duration of symptoms at baseline | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [37] 1 cohort [19] |

No No |

||

| Having another disease (comorbidity) | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [16] 1 cohort [39] |

No No |

||

| Morning stiffness | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [16] 1 cohort [51] |

No No |

||

| Use of pain medication at baseline | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [16] 1 cohort [19] |

No No |

||

| Presence of Heberden’s or Bouchard’s nodes | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [16] |

No No, no |

||

| Previous intra-articular injection in the hip | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [37] | No | ||

| Conflicting evidence | |||

| More limitations in physical function at baseline | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

Positive, positive, no No, no |

|||

| More pain at baseline | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

Conflicted$$, positive, positive Positive, no, positive, no |

|||

| Painful hip flexion (active or passive) | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [16] 1 cohort [51] |

Positive No |

||

| Painful hip internal rotation (active or passive) | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [16] 1 cohort [51] |

Positive No |

||

| Night pain at baseline | Conflicting evidence | ||

| 2 cohorts [50, 51] | Positive, no | ||

| Limited range of motion of flexion of the hip | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [16] |

Positive Positive, no |

||

| Limited range of motion of internal hip rotation | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [16] |

Positive Positive, no |

||

| Limited range of motion of external hip rotation | Conflicting evidence | ||

| 2 cohorts [19, 51] | Positive, no | ||

| Chemical or imaging markers | |||

| Faster or more progression | |||

| Higher K-L grade at baseline | Strong evidence for more or faster progression | ||

|

2 low risk of bias cohorts [34, 37] 1 cohorts [51] |

Positive, positive Positive |

||

| Superior or superolateral migration of the femoral head | Strong evidence for more or faster progression | ||

|

2 low risk of bias cohorts [34, 47] 1 cohort [38] |

Positive, positive Positive |

||

| Subchondral sclerosis | Strong evidence for more progression | ||

| 2 low risk of bias cohorts [16, 47] | Positive, positive | ||

| Statistical shape modeling | Moderate evidence that certain modes of SSM can predict progression | ||

| 3 cohorts [11, 12, 12] | Positive, positive, positive | ||

| Joint space narrowing at baseline | Moderate evidence for more or faster progression | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [16] 1 cohort [67] |

Positive Positive |

||

| No association | |||

| Cam-type deformity (alpha angle > 60°) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [16] | No | ||

| Conflicting evidence | |||

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [16] 1 cohort [51] |

Positive No |

||

| Atrophic bone response (no osteophytes present) | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [16] |

Positive Positive, no |

||

| Decrease in joint space width at baseline | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [34] 1 cohort [51] |

Positive No |

||

| Wiberg’s center edge angle (CEA) | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [16] 1 cohort [20] |

Negative No |

||

$Exception: age ≥ 82 years showed a negative association with progression, compared to age ≤ 62 years

$$Pain at baseline measured with NRS past week showed a statistically significant positive association with THR; pain at baseline measured with WOMAC pain showed no statistically significant association with THR

Strong evidence was found for no association between radiological progression and the following markers: C-terminal telopeptide of collagen type I (CTX-I), cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP), N-terminal telopeptide of collagen type I (NTX-I), and N-terminal propeptide of procollagen type I and type III (PINP, PIIINP) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors predicting radiological progression

| Prognostic factor | Studies | Associations | Best-evidence synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient variables | |||

| No association | |||

| Family history of OA | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

| 3 cohorts [25, 60, 65] | No, no, no | ||

| Body mass index | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

| 4 cohorts [25, 50, 61, 65] | No, no, no, no | ||

| Conflicting evidence | |||

| Higher age at baseline or at first symptoms | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [32] |

Positive No, positive, positive, no |

||

| Female | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [32] |

Positive No, no, no, no, positive, no |

||

| Disease characteristics | |||

| Faster or more progression | |||

| More limitations in physical function at baseline | Moderate evidence for more progression | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [32] 1 cohort [60] |

Positive Positive |

||

| Hip pain present at baseline or on most days for a least 1 month in the past year | Moderate evidence for more progression | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [47] 1 cohort [60] |

Positive Positive |

||

| No association | |||

| Forestier’s disease | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

| 3 cohorts [25, 50, 65] | No, no, no | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 2 cohorts [25, 60] | No, no | ||

| Bilateral hip OA | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 2 cohorts [25, 65] | No, no | ||

| Generalized OA | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 2 cohorts [25, 65] | No, no | ||

| Chemical or imaging markers | |||

| Faster or more progression | |||

| Subchondral sclerosis | Moderate evidence for more progression | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [47] 1 cohort [33] |

Positive Positive |

||

| Neck width of the femoral head | Limited evidence for more progression | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [21] | Positive | ||

| Osteocalcin (OC) | Limited evidence for less progression | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [63] | Negative | ||

| No association | |||

| C-terminal telopeptide of collagen type I (CTX-I) | Strong evidence for no association | ||

| 2 low risk of bias cohorts [53, 63] | No, no | ||

| Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) | Strong evidence for no association | ||

|

3 low risk of bias cohorts [44, 53, 63] 1 cohort [26] |

No, no, no Positive |

||

| N-terminal telopeptide of collagen type I (NTX-I) | Strong evidence for no association | ||

| 2 low risk of bias cohorts [44, 63] | No, no | ||

| N-terminal propeptide of procollagen type I (PINP) | Strong evidence for no association | ||

| 2 low risk of bias cohorts [53, 63] | No, no | ||

| N-terminal propeptide of procollagen type III (PIIINP) | Strong evidence for no association | ||

| 2 low risk of bias cohorts [53, 63] | No, no | ||

| High-sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [53] 1 cohort [45] |

No No |

||

| Angle of the femoral head | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [21] |

No No, no |

||

| Acetabular osteophytes only | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [47] 1 cohort [33] |

No No |

||

| N-terminal propeptide of procollagen type IIA (PIIANP) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [63] | No | ||

| Chondroitin sulphate 846 (CS846) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [63] | No | ||

| Cartilage glycoprotein 40 (YKL-40) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [53] | No | ||

| Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [53] | No | ||

| Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-3) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [53] | No | ||

| Neck length of the femoral head | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [21] | No | ||

| Conflicting evidence | |||

| Bone mineral content | Conflicting evidence | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [21] | Conflicted$ | ||

| Area/size of the hip joint | Conflicting evidence | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [21] | Conflicted$$ | ||

| C-terminal telopeptide of collagen type II (CTX-II) | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

2 low risk of bias cohorts [53, 63] 1 cohort [59] |

Positive, no Positive |

||

| Hyaluronic acid (HA) | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

2 low risk of bias cohorts [53, 63] 1 cohort [23] |

Positive, no No |

||

| Atrophic bone response (no osteophytes present) | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [47] |

No Positive, positive, no |

||

| Subchondral cysts | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [47] 1 cohort [33] |

Positive No |

||

| Decrease in joint space width at baseline | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [32] |

Positive No, positive |

||

| Superior or (supero) lateral migration of the femoral head | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

Positive, no No, positive |

|||

| Higher K-L grade at baseline | Conflicting evidence | ||

| 4 cohorts [33, 50, 60, 65] | No, positive, positive, no | ||

| Acetabular index (Horizontal toit externe angle) | Conflicting evidence | ||

| 2 cohorts [20, 65] | Conflicted$$$, no | ||

| Wiberg’s center edge angle (CEA) | Conflicting evidence | ||

| 2 cohorts [20, 65] | No, negative | ||

$BMC of superior (p = 0.009) and medial (p = 0.019) quart femoral head, arc regions 2–4 (p = 0.02, 0.001, 0.003, respectively), and the acetabular arc was higher in patients with progression than without progression. BMC of the femoral neck (p = 0.17), intertrochanteric area (p = 0.9), trochanteric area (p = 0.6), and inferior (p = 0.08) and lateral (p = 0.06) quart femoral head and arc region 1 (p = 0.19) of acetabular arc was not significantly different between patients with or without progression

$$The area/size of superior (p = 0.002), medial (p = 0.002), inferior (p = 0.003), and lateral (p = 0.003) femoral head and of arc regions 2–4 (p = 0.007, 0.001 and 0.005 respectively) of acetabular arc was higher in patients with progression than without progression. The area/size of the femoral neck (p = 0.6), intertrochanteric area (p = 0.16), trochanteric area (p = 0.4), and arc region 1 (p = 0.2) of the acetabular arc was not significantly different between patients with progression and without progression.

$$$A statistically significant association was found between the acetabular index and progression defined as ≥ 1 increase in joint space narrowing; however, no statistically significant association was found between the acetabular index and progression defined as ≥ 1 increase in K-L grade

Strong evidence showed comorbidity to be predictive of clinical progression. On the other hand, gender, social support, use of pain medication at baseline, quality of life at baseline, and limited range of motion of internal hip rotation or external hip rotation were not predictive of clinical progression (Table 5).

Table 5.

Factors predicting clinical progression

| Prognostic factor | Studies | Associations | Best-evidence synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient variables | |||

| No association | |||

| Female | Strong evidence for no association | ||

|

No, no Positive, no, no, no, no |

|||

| Social support | Strong evidence for no association | ||

| 2 low risk of bias cohorts [41, 57] | No, no | ||

| Higher age at baseline | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

No, positive No, no, no |

|||

| Paid employment | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [41] |

No No, no |

||

| Living alone | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [41] 1 cohort [30] |

No No |

||

| Alcohol consumption | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [41] | No | ||

| Conflicting evidence | |||

| Physical activity during leisure | Conflicting evidence | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [41] | Conflicted$ | ||

| Body mass index | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

Positive, no No, no, positive |

|||

| Lower education level | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

No, negative Positive, no |

|||

| Disease characteristics | |||

| Faster or more progression | |||

| Having another disease (comorbidity) | Strong evidence for more progression | ||

|

2 low risk of bias cohorts [41, 57] 1 cohort [42] |

Positive$$, positive Positive |

||

| Concurrent morning stiffness of the knee (< 30 min) | Limited evidence for more progression | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [41] | Positive | ||

| No association | |||

| Use of (pain) medication at baseline | Strong evidence for no association | ||

| 2 low risk of bias cohorts [29, 41] | No, no | ||

| Quality of life at baseline | Strong evidence for no association | ||

| 2 low risk of bias cohort [30, 41] | No$$$, no | ||

| Limited range of motion of internal hip rotation | Strong evidence for no association | ||

|

2 low risk of bias cohorts [41, 57] 1 cohort [66] |

No, no No |

||

| Limited range of motion of external hip rotation | Strong evidence for no association | ||

| 2 low risk of bias cohorts [15, 57] | No, no | ||

| Concurrent knee pain | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [41] 1 cohort [66] |

No No |

||

| Depression | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [41] 1 cohort [56] |

No No |

||

| Way of coping | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [41] 1 cohort [30] |

No No |

||

| Respiratory comorbidity | Moderate evidence for no association | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [29] 1 cohort [56] |

No No |

||

| Patient-rated health | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [41] | No | ||

| Cardiac comorbidity (cumulative illness rating scale 1, severity score ≥ 2) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [29] | No | ||

| Vascular comorbidity (cumulative illness rating scale 2, severity score ≥ 2) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [29] | No | ||

| Eye, ear, nose, throat, and larynx diseases (cumulative illness rating scale 4, severity score ≥ 2) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [29] | No | ||

| Upper gastrointestinal comorbidity (cumulative illness rating scale 5, severity score ≥ 2) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [29] | No | ||

| Lower gastrointestinal comorbidity (cumulative illness rating scale 6, severity score ≥ 2) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [29] | No | ||

| Hepatic comorbidity (cumulative illness rating scale 7, severity score ≥ 2) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [29] | No | ||

| Renal comorbidity (cumulative illness rating scale 8, severity score ≥ 2) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [29] | No | ||

| Other genitourinary comorbidities (cumulative illness rating scale 9, severity score ≥ 2) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [29] | No | ||

| Neurological comorbidity (cumulative illness rating scale 11, severity score ≥ 2) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [29] | No | ||

| Psychiatric comorbidity (cumulative illness rating scale 12, severity score ≥ 2) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [29] | No | ||

| Comorbidity of endocrine and metabolic diseases (cumulative illness rating scale 13, severity score ≥ 2) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [29] | No | ||

| Cognitive functioning | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [57] | No | ||

| Muscle strength hip abduction | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [57] | No | ||

| Pain during sitting or lying | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [41] | No | ||

| Joint stiffness (WOMAC) | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [15] | No | ||

| Use of additional supplements or vitamins | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [15] | No | ||

| Concurrent pain during flexion of ipsilateral knee | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [15] | No | ||

| Knee flexion | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [29] | No | ||

| Knee extension | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [29] | No | ||

| Strength of isometric knee extension | Limited evidence for no association | ||

| 1 low risk of bias cohort [29] | No | ||

| Conflicting evidence | |||

| Bilateral hip OA | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [41] 1 cohort [66] |

Positive, if equal symptoms No |

||

| Pain at baseline (self-reported or during physical examination) | Conflicting evidence | ||

| 3 low risk of bias cohorts [29, 41, 47] | No, no, positive | ||

| Longer duration of symptoms at baseline | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [57] |

No No, positive |

||

| Morning stiffness | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [41] 1 cohort [66] |

No Positive |

||

| Limited range of motion of flexion of the hip | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

2 low risk of bias cohorts [41, 57] 1 cohort [66] |

Positive, no No |

||

| Chemical or imaging markers | |||

| Conflicting evidence | |||

| Higher K-L grade at baseline | Conflicting evidence | ||

|

1 low risk of bias cohort [12] |

No No, positive |

||

$Patients who were 3–5 days/week physically active in their leisure time showed less progression than patients who were 0–2 days/week physically active in their leisure time. No difference was found between patients spending 6–7 days/week on physical activity and patients spending 0–2 days/week on physical activity

$$≥ 3 more diseases compared to no comorbidities

$$$Subscale of SF-36 vitality showed a positive association with WOMAC function score

For other factors, only moderate, limited, or conflicting evidence was found for predicting or not predicting progression (Tables 3, 4, and 5).

Discussion

In this study, we systematically reviewed all 154 factors predictive of progression of hip OA, reported in 57 studies. Compared to earlier reviews, there was a considerable amount of additional evidence available for the factors previously reported in reviews, as well as evidence for factors not earlier described.

In this review, some results had changed compared to the review of Lievense et al. in 2002 [2]. Firstly, because of the new evidence emerging from the later studies, especially studies with a clinical outcome of progression. Secondly, because we used a different method to assess the risk of bias, some studies were no longer considered to have a low risk of bias. The QUIPS tool seems to apply stricter criteria than the method used by Lievense et al. in 2002. Thirdly, we divided the outcomes into three different groups of progression. Thus, due to these methodological differences (together with additional studies), we were unable to confirm an atrophic bone response as a predictor for radiological progression or progression to THR. On the other, we were able to confirm their conclusion on BMI as not predictive of progression and faster progression in patients with a superolateral migration of the femoral head.

Most of the prognostic factors reported by Wright et al. in 2009 [3] were confirmed in this present review in one or more of the outcome groups. The differences found in age, femoral and acetabular osteophytes, and hip pain at baseline were (as with Lievense et al.) a combination of new evidence, differences in the risk of bias assessment, and the division into defined groups of progression. The study from de Rooij et al. in 2016 [4] reviewed the evidence for predictors of the course of pain and function and found comorbidity and vitality (SF-36) to be predictive of function, as we found for clinical progression. However, although they also used the QUIPS tool to assess the risk of bias, they used a different cutoff point to classify a study as having a low risk of bias. Therefore, some earlier findings of strong evidence for no association with the course of pain or function were confirmed as only moderate evidence for no association with clinical progression in our review. Other differences between this review and the present one are mainly attributable to the differences in the selection criteria. In Table 6, we summarized all factors with strong evidence to be predictive of progression found in one of these four reviews and the overlap and differences in evidence for these factors.

Table 6.

Overview of factors with strong evidence to be predictive of progression, overlap and differences between this review and the review of de Rooij et al., Wright et al., and Lievense et al.

| Prognostic factor | Teirlinck et al. factor predictive of | De Rooij et al. factor predictive of | Wright et al. factor predictive of | Lievense et al. factor predictive of |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-L grade at baseline | THR | Strong evidence for no association for clinical progression | Radiological progression or THR* | Not mentioned |

| Subchondral sclerosis at baseline | THR | Not mentioned | Radiological progression and/or THR | Not mentioned |

| Superior or (supero) lateral femoral head migration | THR | Not mentioned | Radiological progression and/or THR | Radiological progression and/or THR |

| Comorbidity | Clinical progression | Clinical progression (strong evidence for a course of function, weak evidence for a course of pain) | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Low vitality | Quality of life in general: strong evidence of no association, specific for SF 36 vitality: strong evidence for clinical progression | Course of function | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Age | Conflicted evidence for THR and radiological progression, moderate evidence for no association with clinical progression | Strong evidence for no association with pain and conflicted evidence for function | Radiological progression and/or THR | Conflicted evidence |

| Femoral osteophytes | Conflicted evidence | Not mentioned | Radiological progression and/or THR | Not mentioned |

| Hip pain at baseline | Conflicted evidence | Conflicted evidence | Radiological progression and THR | Not mentioned |

| JSW at baseline | Conflicted evidence | Not mentioned | Radiological progression and/or THR | Limited evidence for THR |

| Lequesne index score ≥ 10 at baseline | Conflicted evidence for THR, moderate evidence for radiological progression** | Conflicted evidence** | Radiological progression and/or THR | Not mentioned |

| Atrophic bone response | Conflicted evidence | Not mentioned | Conflicted evidence | Radiological progression |

*K-L grade 3 at baseline

**Function at baseline in general

bold text represents strong evidence to be predictive of progression

Strengths of this present review are the sensitive literature search and our systematic approach to the selection, risk of bias assessment, and the best-evidence synthesis. Therefore, we have presented an extensive overview of reported prognostic factors and existing evidence for their associations. In performing the evidence synthesis divided into outcome (radiological, clinical, or THR), we decreased the heterogeneity and we believe the results to be more accurate for daily practice. Unfortunately, heterogeneity was still too high to perform a meta-analysis. Therefore, we were bound to a best-evidence synthesis and unable to calculate the strengths of the associations. This limits the translation to the daily clinical practice. Another disadvantage of this synthesis compared to a meta-analysis is that smaller studies contribute to the result with the same weight as larger studies, even though the smaller studies may have low power to show a statistically significant association.

In the selection of studies, several restrictions were imposed. First, languages were restricted to ensure that at least two researchers had a reasonable understanding of the languages included so all articles were reliably assessed. However, this implies that we may have missed studies from countries in which publication in English is less common. Secondly, negative results (i.e., no association was found) are less likely to be published and are therefore not well represented in this review.

We used the QUIPS tool to assess the risk of bias. Nine other studies using this tool reported an inter-rater agreement ranging from 70 to 89.5% (median 83.5%) and a kappa statistic ranging from 0.56 to 0.82 (median 0.75) [7]. Compared to these data, our inter-rater agreement was low and considered to be moderate. Disagreement was mainly due to the differences in interpretation of items of the QUIPS tool; however, only for very few items, a third reviewer was needed to make a final decision.

Hip dysplasia and femoral acetabular impingement were initially considered to be underlying pathologies and were excluded from this analysis. However, the range of severity of these morphologies is substantial, i.e., some of these morphologies should clearly be considered as an underlying pathology, whereas others are more subtle and sometimes undiagnosed. These subtle morphologies might be considered to be possible prognostic factors, rather than underlying pathologies. Therefore, all citations were screened using the terms “hip dysplasia” and “femoral acetabular impingement” in the title or abstract. However, we found only one small study [35] which investigated the radiographic findings of femoral acetabular impingement as a prognostic factor (results of this study are included in Additional file 4). In the studies already included, three studies did not specifically include patients with hip dysplasia or femoral acetabular impingement but did investigate the associated angles (Wiberg’s center edge angle and alpha angle, respectively). Since the evidence for these associations with the progression of hip OA was weak, future studies and reviews should investigate these morphologies as possible prognostic factors.

Conclusion

We conclude that there is consistent evidence that four factors (comorbidity, K-L grade, superior or (supero) lateral femoral head migration, and subchondral sclerosis) were predictive of progression of hip OA, whereas 12 factors were not predictive. The evidence for other factors was weak or conflicting. Health professionals caring for patients with hip OA will benefit from the insight in prognostic factors, e.g., patients more likely to progress rapidly may need an intensified symptomatic treatment or early referral to an orthopedic surgeon. For this, we still need more high-quality research focusing on the prognostic factors in hip OA.

Additional files

Syntax of literature search. (DOCX 15 kb)

Criteria items of QUIPS tool and possible adjustments. (DOCX 42 kb)

Characteristics of the selected studies: extensive overview. (DOCX 172 kb)

Prognostic factors described by one study or multiple studies from the same cohort. (DOCX 126 kb)

Factors predicting total hip replacement, clinical or radiological progression combined. (DOCX 82 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Wichor Bramer for assisting with the literature search and Nadine Rasenberg and Mohammed Boudjemaoui for assisting with the selection, assessment, and data extraction of the French-language literature.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- COMP

Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein

- CS846

Chondroitin sulphate 846

- CTX-I

C-terminal telopeptide of collagen type I

- CTX-III

C-terminal telopeptide of collagen type II

- ESR

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- HA

Hyaluronic acid

- hs-CRP

High-sensitive C-reactive protein

- JSN

Joint space narrowing

- JSW

Joint space width

- K-L grade

Kellgren and Lawrence grade

- LCGA

Latent class growth analysis

- MJS

Minimum joint space

- MMP-1

Matrix metalloproteinases-1

- MMP-3

Matrix metalloproteinases-3

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NRS

Numeric rating scale

- NTX-I

N-terminal telopeptide of collagen type I

- OA

Osteoarthritis

- OC

Osteocalcin

- PIIANP

N-terminal propeptide of procollagen type IIA

- PIIINP

N-terminal propeptide of procollagen type III

- PINP

N-terminal propeptide of procollagen type I

- QUIPS

Quality in prognosis studies

- THR

Total hip replacement

- VAS

Visual analog scale

- WOMAC

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index

- YKL-40

Cartilage glycoprotein 40

- YMN

Yearly mean narrowing

Authors’ contributions

CHT was responsible for the methods, search, selection, data extraction, assessment, analysis, and drafting the article. DMJD, PKB, and SMABZ were responsible for the methods, assessment, and critical revision of the article. JBMRO was responsible for the assessment and critical revision of the article. PAJL was responsible for the methods, selection, data extraction, assessment, analysis, and extensive revision of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by a program grant from the Dutch Arthritis Foundation for their center of excellence “Osteoarthritis in primary care”.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

Dr. Bierma-Zeinstra reports grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (Health Care Efficiency Research Programme), during the conduct of the study; grants from Dutch Arthritis Foundation, the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development, and EU Horizon 2020, Stichting Coolsingel, Nuts-Ohra, and EU Fp7, other from Regeneron, and Infirst Healthcare; personal fees from Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; personal fees from OARSI, EULAR, Regeneron, and Infirst Healthcare, outside the submitted work. The other authors certify that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

C. H. Teirlinck, Email: c.teirlinck@erasmusmc.nl

D. M. J. Dorleijn, Email: desireedorleijn@hotmail.com

P. K. Bos, Email: p.k.bos@erasmusmc.nl

J. B. M. Rijkels-Otters, Email: j.rijkels-otters@erasmusmc.nl

S. M. A. Bierma-Zeinstra, Email: s.bierma-zeinstra@erasmusmc.nl

P. A. J. Luijsterburg, Email: p.luijsterburg@erasmusmc.nl

References

- 1.Litwic A, Edwards MH, Dennison EM, Cooper C. Epidemiology and burden of osteoarthritis. Br Med Bull. 2013;105:185–199. doi: 10.1093/bmb/lds038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lievense AM, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Verhagen AP, Verhaar JA, Koes BW. Prognostic factors of progress of hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47(5):556–562. doi: 10.1002/art.10660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright AA, Cook C, Abbott JH. Variables associated with the progression of hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(7):925–936. doi: 10.1002/art.24641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Rooij M, van der Leeden M, Heymans MW, Holla JF, Hakkinen A, Lems WF, Roorda LD, Veenhof C, Sanchez-Ramirez DC, de Vet HC, et al. Course and predictors of pain and physical functioning in patients with hip osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48(3):245–252. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayden JA, Cote P, Bombardier C. Evaluation of the quality of prognosis studies in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(6):427–437. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-6-200603210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altman RD, Bloch DA, Dougados M, Hochberg M, Lohmander S, Pavelka K, Spector T, Vignon E. Measurement of structural progression in osteoarthritis of the hip: the Barcelona consensus group. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2004;12(7):515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, Cote P, Bombardier C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):280–286. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huguet A, Hayden JA, Stinson J, McGrath PJ, Chambers CT, Tougas ME, Wozney L. Judging the quality of evidence in reviews of prognostic factor research: adapting the GRADE framework. Syst Rev. 2013;2:71. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis P, Hayden J, Springer J, Bailey J, Molinari M, Johnson P. Prognostic factors for morbidity and mortality in elderly patients undergoing acute gastrointestinal surgery: a systematic review. Can J Surg. 2014;57(2):E44–E52. doi: 10.1503/cjs.006413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ernster VL. Nested case-control studies. Prev Med. 1994;23(5):587–590. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agricola R, Reijman M, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Verhaar JAN, Weinans H, Waarsing JH. Total hip replacement but not clinical osteoarthritis can be predicted by the shape of the hip: a prospective cohort study (CHECK) Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2013;21(4):559–564. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agricola R, Leyland KM, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Thomas GE, Emans PJ, Spector TD, Weinans H, Waarsing JH, Arden NK. Validation of statistical shape modelling to predict hip osteoarthritis in females: data from two prospective cohort studies (Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee and Chingford) Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54(11):2033–2041. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Auquier L, Paolaggi JB, Cohen De Lara A. Long term evolution of pain in a series of 273 coxarthrosis. Rev Rhum Mal Osteo-Articul. 1979;46(3):153–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barr RJ, Gregory JS, Reid DM, Aspden RM, Yoshida K, Hosie G, Silman AJ, Alesci S, Macfarlane GJ. Predicting OA progression to total hip replacement: can we do better than risk factors alone using active shape modelling as an imaging biomarker? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51(3):562–570. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bastick AN, Verkleij SPJ, Damen J, Wesseling J, Hilberdink WKHA, Bindels PJE, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA. Defining hip pain trajectories in early symptomatic hip osteoarthritis - 5 year results from a nationwide prospective cohort study (CHECK) Osteoarthr Cartil. 2016;24(5):768–775. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bastick AN, Damen J, Agricola R, Brouwer RW, Bindels PJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Characteristics associated with joint replacement in early symptomatic knee or hip osteoarthritis: 6-year results from a nationwide prospective cohort study (CHECK) Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(663):e724–e731. doi: 10.3399/bjgp17X692165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergink AP, Zillikens MC, Van Leeuwen JPTM, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, van Meurs JBJ. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis including new data. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45(5):539–546. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birn J, Pruente R, Avram R, Eyler W, Mahan M, van Holsbeeck M. Sonographic evaluation of hip joint effusion in osteoarthritis with correlation to radiographic findings. J Clin Ultrasound. 2014;42(4):205–211. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birrell F, Afzal C, Nahit E, Lunt M, Macfarlane GJ, Cooper C, Croft PR, Hosie G, Silman AJ. Predictors of hip joint replacement in new attenders in primary care with hip pain. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(486):26–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouyer B, Mazieres B, Guillemin F, Bouttier R, Fautrel B, Morvan J, Pouchot J, Rat AC, Roux CH, Verrouil E, et al. Association between hip morphology and prevalence, clinical severity and progression of hip osteoarthritis over 3 years: the knee and hip osteoarthritis long-term assessment cohort results. Jt Bone Spine. 2016;83(4):432–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castano Betancourt MC, Van der Linden JC, Rivadeneira F, Rozendaal RM, Bierma Zeinstra SM, Weinans H, Waarsing JH. Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry analysis contributes to the prediction of hip osteoarthritis progression. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(6):R162. doi: 10.1186/ar2845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaganti RK, Kelman A, Lui L, Yao W, Javaid MK, Bauer D, Nevitt M, Lane NE, for the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research G Change in serum measurements of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein and association with the development and worsening of radiographic hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2008;16(5):566–571. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chevalier X, Conrozier T, Gehrmann M, Claudepierre P, Mathieu P, Unger S, Vignon E. Tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease-1 (TIMP-1) serum level may predict progression of hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2001;9(4):300–307. doi: 10.1053/joca.2000.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conrozier T, Chappuis-Cellier C, Richard M, Mathieu P, Richard S, Vignon E. Increased serum C-reactive protein levels by immunonephelometry in patients with rapidly destructive hip osteoarthritis. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1998;65(12):759–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conrozier T, Jousseaume CA, Mathieu P, Tron AM, Caton J, Bejui J, Vignon E. Quantitative measurement of joint space narrowing progression in hip osteoarthritis: a longitudinal retrospective study of patients treated by total hip arthroplasty. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37(9):961–968. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.9.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conrozier T, Saxne T, Fan CSS, Mathieu P, Tron AM, Heinegard D, Vignon E. Serum concentrations of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein and bone sialoprotein in hip osteoarthritis: a one year prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57(9):527–532. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.9.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Danielsson LG. Incidence and prognosis of coxarthrosis. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1964;66(SUPPL 66):61–114. doi: 10.3109/ort.1964.35.suppl-66.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danielsson LG. Incidence and prognosis of coxarthrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;287:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Dijk GM, Veenhof C, Spreeuwenberg P, Coene N, Burger BJ, van Schaardenburg D, van den Ende CH, Lankhorst GJ, Dekker J. Prognosis of limitations in activities in osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a 3-year cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(1):58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.08.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Dijk GM, Veenhof C, Lankhorst GJ, Van Den Ende CH, Dekker J. Vitality and the course of limitations in activities in osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:269. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dorleijn DMJ, Luijsterburg PAJ, Bay-Jensen AC, Siebuhr AS, Karsdal MA, Rozendaal RM, Bos PK, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA. Association between biochemical cartilage markers and clinical symptoms in patients with hip osteoarthritis: cohort study with 2-year follow-up. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2015;23(1):57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dougados M, Gueguen A, Nguyen M, Berdah L, Lequesne M, Mazieres B, Vignon E. Radiological progression of hip osteoarthritis: definition, risk factors and correlations with clinical status. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55(6):356–362. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.6.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dougados M, Gueguen A, Nguyen M, Berdah L, Lequesne M, Mazieres B, Vignon E. Radiographic features predictive of radiographic progression of hip osteoarthritis. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1997;64(12):795–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dougados M, Gueguen A, Nguyen M, Berdah L, Lequesne M, Mazieres B, Vignon E. Requirement for total hip arthroplasty: an outcome measure of hip osteoarthritis? J Rheumatol. 1999;26(4):855–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fukushima K, Inoue G, Uchida K, Fujimaki H, Miyagi M, Nagura N, Uchiyama K, Takahira N, Takaso M. Relationship between synovial inflammatory cytokines and progression of osteoarthritis after hip arthroscopy. Exp Assess. J Orthop Surg. 2018;26(2):1-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Golightly YM, Allen KD, Helmick CG, Schwartz TA, Renner JB, Jordan JM. Hazard of incident and progressive knee and hip radiographic osteoarthritis and chronic joint symptoms in individuals with and without limb length inequality. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(10):2133–2140. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.091410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gossec L, Tubach F, Baron G, Ravaud P, Logeart I, Dougados M. Predictive factors of total hip replacement due to primary osteoarthritis: a prospective 2 year study of 505 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(7):1028–1032. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.029546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartofilakidis G, Karachalios T. Idiopathic osteoarthritis of the hip: incidence, classification, and natural history of 272 cases. Orthopedics. 2003;26(2):161–166. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20030201-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hawker GA, Guan J, Croxford R, Coyte PC, Glazier RH, Harvey BJ, Wright JG, Williams JI, Badley EM. A prospective population-based study of the predictors of undergoing total joint arthroplasty. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(10):3212–3220. doi: 10.1002/art.22146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoeven TA, Kavousi M, Clockaerts S, Kerkhof HJM, Van Meurs JB, Franco O, Hofman A, Bindels P, Witteman J, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Association of atherosclerosis with presence and progression of osteoarthritis: the Rotterdam Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(5):646–651. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holla JFM, Steultjens MPM, Roorda LD, Heymans MW, Ten Wolde S, Dekker J. Prognostic factors for the two-year course of activity limitations in early osteoarthritis of the hip and/or knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(10):1415–1425. doi: 10.1002/acr.20263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Juhakoski R, Malmivaara A, Lakka TA, Tenhonen S, Hannila ML, Arokoski JP. Determinants of pain and functioning in hip osteoarthritis - a two-year prospective study. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27(3):281–287. doi: 10.1177/0269215512453060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalyoncu U, Gossec L, Nguyen M, Berdah L, Mazieres B, Lequesne M, Dougados M. Self-reported prevalence of psoriasis and evaluation of the impact on the natural history of hip osteoarthritis: results of a 10 years follow-up study of 507 patients (ECHODIAH study) Jt Bone Spine. 2009;76(4):389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelman A, Lui L, Yao W, Krumme A, Nevitt M, Lane NE. Association of higher levels of serum cartilage oligomeric matrix protein and N-telopeptide crosslinks with the development of radiographic hip osteoarthritis in elderly women. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):236–243. doi: 10.1002/art.21527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kerkhof HJM, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Castano-Betancourt MC, De Maat MP, Hofman A, Pols HAP, Rivadeneira F, Witteman JC, Uitterlinden AG, Van Meurs JBJ. Serum C reactive protein levels and genetic variation in the CRP gene are not associated with the prevalence, incidence or progression of osteoarthritis independent of body mass index. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(11):1976–1982. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.125260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kopec JA, Sayre EC, Schwartz TA, Renner JB, Helmick CG, Badley EM, Cibere J, Callahan LF, Jordan JM. Occurrence of radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee and hip among african americans and whites: a population-based prospective cohort study. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65(6):928–935. doi: 10.1002/acr.21924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lane NE, Nevitt MC, Hochberg MC, Hung YY, Palermo L. Progression of radiographic hip osteoarthritis over eight years in a community sample of elderly white women. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(5):1477–1486. doi: 10.1002/art.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lane NE, Nevitt MC, Lui LY, De Leon P, Corr M. Wnt signaling antagonists are potential prognostic biomarkers for the progression of radiographic hip osteoarthritis in elderly Caucasian women. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(10):3319–3325. doi: 10.1002/art.22867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laslett LL, Quinn S, Burgess JR, Parameswaran V, Winzenberg TM, Jones G, Ding C. Moderate vitamin D deficiency is associated with changes in knee and hip pain in older adults: a 5-year longitudinal study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(4):697–703. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ledingham J, Dawson S, Preston B, Milligan G, Doherty M. Radiographic progression of hospital referred osteoarthritis of the hip. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52(4):263–267. doi: 10.1136/ard.52.4.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lievense AM, Koes BW, Verhaar JAN, Bohnen AM, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA. Prognosis of hip pain in general practice: a prospective followup study. Arthritis Care Res. 2007;57(8):1368–1374. doi: 10.1002/art.23094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maillefert JF, Gueguen A, Monreal M, Nguyen M, Berdah L, Lequesne M, Mazieres B, Vignon E, Dougados M. Sex differences in hip osteoarthritis: results of a longitudinal study in 508 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(10):931–934. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.10.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mazieres B, Garnero P, Gueguen A, Abbal M, Berdah L, Lequesne M, Nguyen M, Salles JP, Vignon E, Dougados M. Molecular markers of cartilage breakdown and synovitis at baseline as predictors of structural progression of hip osteoarthritis. The ECHODIAH* cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(3):354–359. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.037275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nelson AE, Golightly YM, Kraus VB, Stabler T, Renner JB, Helmick CG, Jordan JM. Serum transforming growth factor-beta 1 is not a robust biomarker of incident and progressive radiographic osteoarthritis at the hip and knee: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2010;18(6):825–829. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perry GH, Smith MJ, Whiteside CG. Spontaneous recovery of the joint space in degenerative hip disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 1972;31(6):440–448. doi: 10.1136/ard.31.6.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peters TJ, Sanders C, Dieppe P, Donovan J. Factors associated with change in pain and disability over time: a community-based prospective observational study of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(512):205–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pisters MF, Veenhof C, van Dijk GM, Heymans MW, Twisk JWR, Dekker J. The course of limitations in activities over 5 years in patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis with moderate functional limitations: risk factors for future functional decline. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2012;20(6):503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pollard TCB, Batra RN, Judge A, Watkins B, McNally EG, Gill HS, Arden NK, Carr AJ. Genetic predisposition to the presence and 5-year clinical progression of hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2012;20(5):368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reijman M, Hazes JMW, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Koes BW, Christgau S, Christiansen C, Uitterlinden AG, Pols HAP. A new marker for osteoarthritis: cross-sectional and longitudinal approach. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(8):2471–2478. doi: 10.1002/art.20332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]