Significance

Recent results have shown that nature’s water splitting catalyst inserts an additional water molecule into what appears to be a solvent inaccessible site late in its reaction cycle. The emerging consensus of the field is that this water molecule is one of the substrates of the reaction. Here, we show that this water molecule does not come directly from solvent. It instead represents an earlier bound water, which is inserted into this site via facile structural tautomerism. The trigger for this process is cofactor oxidation. This then allows an additional water to bind from solvent to a more open site of the cofactor. In this way the cofactor carefully regulates water uptake, preventing water insertion earlier in the reaction cycle.

Keywords: Photosystem II, WOC/OEC, EPR, EDNMR, methanol

Abstract

Nature’s water splitting cofactor passes through a series of catalytic intermediates (S0-S4) before O-O bond formation and O2 release. In the second last transition (S2 to S3) cofactor oxidation is coupled to water molecule binding to Mn1. It is this activated, water-enriched all MnIV form of the cofactor that goes on to form the O-O bond, after the next light-induced oxidation to S4. How cofactor activation proceeds remains an open question. Here, we report a so far not described intermediate (S3') in which cofactor oxidation has occurred without water insertion. This intermediate can be trapped in a significant fraction of centers (>50%) in (i) chemical-modified cofactors in which Ca2+ is exchanged with Sr2+; the Mn4O5Sr cofactor remains active, but the S2-S3 and S3-S0 transitions are slower than for the Mn4O5Ca cofactor; and (ii) upon addition of 3% vol/vol methanol; methanol is thought to act as a substrate water analog. The S3' electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) signal is significantly broader than the untreated S3 signal (2.5 T vs. 1.5 T), indicating the cofactor still contains a 5-coordinate Mn ion, as seen in the preceding S2 state. Magnetic double resonance data extend these findings revealing the electronic connectivity of the S3' cofactor is similar to the high spin form of the preceding S2 state, which contains a cuboidal Mn3O4Ca unit tethered to an external, 5-coordinate Mn ion (Mn4). These results demonstrate that cofactor oxidation regulates water molecule insertion via binding to Mn4. The interaction of ammonia with the cofactor is also discussed.

Nature’s water splitting catalyst, a penta-oxygen tetramanganese-calcium cofactor (Mn4O5Ca) is found in a unique protein, Photosystem II (PSII) (1, 2). The catalytic cycle of the cofactor is comprised of 5 distinct redox intermediates, the Sn states, where the subscript indicates the number of stored oxidizing equivalents (n = 0–4) required to split 2 water molecules and release molecular oxygen (3). (Fig. 1A) Importantly, each S-state transition is multistep, with the cofactor’s oxidation coupled to its deprotonation (with the exception of the S1 to S2 transition) and conformational changes (4). S-state progression is driven by the reaction center of PSII, which is a multichlorophyll pigment assembly. Light absorption and charge separation generates an in situ photo-oxidant (P680•+), coupled to the Mn4O5Ca cofactor via an intermediary redox-active tyrosine residue, YZ. After 4 charge separation events, the transiently formed [S4] state rapidly decays to the S0 state with the concomitant release of molecular triplet oxygen and rebinding of one substrate water molecule (5, 6).

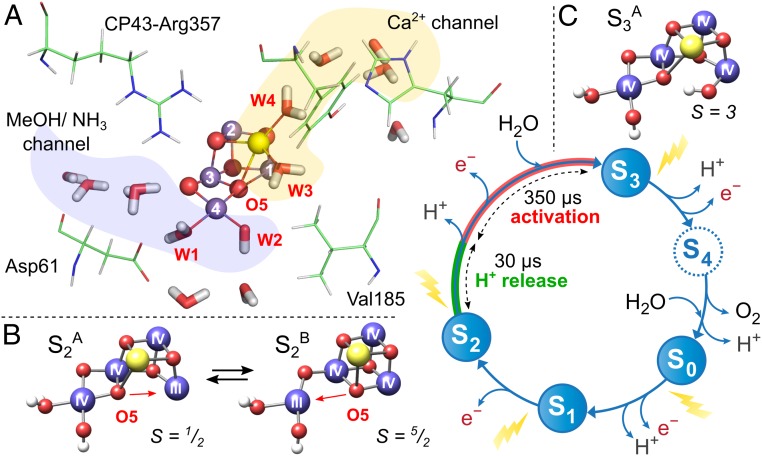

Fig. 1.

The Mn4O5Ca cofactor and its catalytic (Kok) cycle (3). (A) Potential substrate water channels leading to and from the Mn4O5Ca cofactor. (B) The open cubane (S2A, SG = 1/2) and the closed cubane (S2B, SG = 5/2) structures of the S2 state; the 2 S2 state forms differ in their core connectivity by the reorganization of O5 (13). (C) The open cubane (S3A, SG = 3) structure of the S3 state.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) (1) along with more recent X-ray free electron laser (XFEL) measurements (7, 8) have resolved the structure of the Mn4O5Ca cluster in its dark-stable (S1) state. The metal ions form a “distorted chair” with Mn1, Mn2, and Mn3 together with the Ca2+ ion as the base of the “chair,” a Mn3O3Ca open cubane, with the fourth dangler/outer Mn4 connected to the base via 2 oxygen bridges, O4 and O5 (Fig. 1A). The oxidation states of the Mn ions are III, IV, IV, and III.

The water molecules W2 and W3, together with the O5 bridge, are considered the most likely substrate-binding sites in the S1 state (9–12). The structure of the cofactor is, however, dynamic as it progresses through the catalytic cycle. This flexibility first emerges in the S2 state, whose net oxidation state is now (MnIV)3MnIII. Here, the cofactor can adopt 2 interconvertible manganese core topologies (13) involving the movement of the O5 bridge: an open cubane motif (S2A) as seen in the current X-ray (1, 7, 8) and previous DFT (14) structures and a closed cubane motif (S2B) (Fig. 1B). The S2A form displays a low-spin electronic ground state configuration (SG = 1/2) locating the only 5-coordinate Mn, the MnIII ion, within the cuboidal unit (Mn1). In contrast, the S2B form displays a high-spin (SG = 5/2) electronic configuration, in which the position of the 5-coordinate MnIII ion shifts to the “dangler” Mn4 (13, 15).

In the next state, S3, the net oxidation state of the cofactor is all (MnIV)4. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) (16), X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and X-ray emission spectroscopy (XES) (17, 18), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) (19, 20), and recent XFEL data (8, 21) suggest that in this S state, all 4 Mn ions are octahedral, requiring the insertion of a new water molecule into the cofactor. Structural models of the cofactor in the S3 state more closely resemble the preceding S2A form compared with the S2B form, with an additional oxygen (most likely hydroxide) ligand at Mn1 (8, 14, 16, 21) (Fig. 1C). Curiously, however, from an electronic perspective it more closely resembles S2B, exhibiting a high-spin electronic configuration with SG = 3 (16). It is this activated form of the cofactor that goes on to form the O-O bond.

Rationalizing the S2 → S3 transition is thus important for understanding the mechanism of water oxidation. It is at this point in the cycle that inhibitory treatments—the removal of Ca2+ (22) or Cl− (23) and acetate binding to the cofactor (24)—block S-state progression. In unperturbed samples, the entire transition spans 350 μs, with at least 3 discrete phases identified. The initial, ultrafast phase involves light excitation to generate the photo-oxidant P680•+, which is rapidly rereduced by YZ (25). Photo-acoustic beam deflection measurements along with XAS data (17, 26) assign the next 2 phases. The fast 30-μs kinetic phase is attributed to deprotonation of the cluster, with the slow 350-μs phase representing structural rearrangement, e.g., water insertion and cofactor oxidation. A more recent FTIR study suggests that deprotonation may also occur during the slow 350-μs phase (19). In either case, theoretical calculations support the notion that cofactor oxidation only proceeds via redox tuning (deprotonation) of the cofactor. The W1 ligand is considered to be the deprotonation site; it loses its proton via a channel that includes the Asp61 residue (27–30) (Fig. 1A).

There are 4 basic molecular pathways describing the S2 → S3 progression during the slow kinetic phase. They differ in terms of whether the S2A or S2B state progresses to the S3 state, and whether water binding initiates cofactor oxidation or if instead cofactor oxidation is necessary for water binding (15, 28, 31–34). That is to say whether the cofactor progresses via (i) an S2-like (S2' state), in which the cofactor’s net oxidation state is the same as S2 but the cofactor has an additional water-derived ligand; or (ii) an S3-like (S3' state) in which the cofactor’s net oxidation state is the same as S3, but the additional water binding has not yet occurred, Fig. 2 (2, 11).

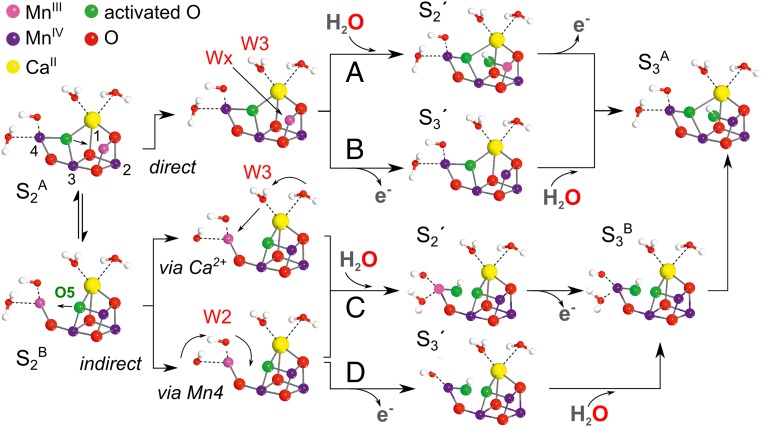

Fig. 2.

4 proposed pathways for water insertion during the S2 to S3 transition leading to the activated cluster. (A) An S2A type structure binds a water molecule (a new water WX or W3) at Mn1 concomitant with its deprotonation (S2'), followed by cofactor oxidation (14). (B) An S2A-type structure first undergoes oxidation (S3') followed by water molecule insertion (WX or W3) at Mn1 and concomitant deprotonation. (C) An S2B type structure binds a water molecule (S2') via either the Ca2+ channel (32, 33) or Asp61 channel, which terminates on the back face of Mn4 (34). Subsequently, Mn4 is oxidized and the cofactor rearranges to give an S3A-type structure (35). (D) An S2B-type structure first undergoes oxidation (S3') followed by water molecule insertion at Mn4 (28) and cofactor rearrangements to give an S3A-type structure (35). Note the cofactor has been rotated 90° compared with Fig. 1.

Recent XFEL measurements provide further details on this sequence (8). Two structures have been collected during the S2 to S3 transition, resolving a lengthening of the Mn1-Mn4 distance that is complete at 150 μs and the buildup of electron density near Mn1 clearly visible at 400 μs. This new density is indicative of water insertion and clearly demonstrates this process is associated with the slow kinetic phase. On that basis, and because of the partial detachment of Glu189 from the Ca2+ ion, which may remove steric constrains for a direct water insertion at Mn1, the authors favored a direct water insertion pathway into an A-type intermediate (Fig. 2 A and B). However, the XFEL data do not exclude short-lived B-type S2'/S3' intermediate(s).

Quantum chemical calculations (28, 32–34) instead favor an indirect water insertion pathway (Fig. 2 C and D). In these models, the 5-coordinate Mn site is first transferred to Mn4, opening a solvent accessible coordination site for water binding. Following water binding and cofactor oxidation, a transient S3B type structure is formed. This can then progress to S3A by shuttling a proton between the 2 oxygens bound on the Mn1/Mn4 axis (35), a process which presumably involves short range (≈2 Å) proton tunneling (36). An interesting feature of these mechanisms is that the water that binds to the cofactor does not need to be the site of deprotonation (28, 33, 34), allowing the redox tuning event to occur first via the W1/Asp61 residue, as described above.

High-field EPR spectroscopy is a powerful tool to study the S2 to S3 transition as it is able to both monitor the oxidation and ligand state of all 4 Mn ions. One way to potentially trap such intermediates (S2', S3') is to add small molecules, which mimic the water molecule to be inserted, i.e., methanol (MeOH) or ammonia (NH3). Both these molecules associate with the water channels of PSII leading to the catalyst but do not inhibit catalysis, although there is evidence that they render S-state advancement less efficient (37, 38). In the case of methanol, it associates with the channel that terminates at Mn4 (Asp61 channel) and possibly also the channel that terminates at the Ca2+ (39) (Fig. 1A). However, it does not directly interact with the Mn ions, which make up the cluster (40). In the case of ammonia, it associates with the Asp61 channel, displacing the W1 water ligand on Mn4 (9, 41, 42). An alternative approach is to chemically modify the cofactor by biosynthetically replacing the Ca2+ ion with Sr2+. This modified cofactor is still catalytically competent but has a slower O-O bond formation rate. In the precursor S2 state, all these systems display similar EPR (multiline) spectra compared with wild type (9, 41, 43, 44). In this article we report that the addition of methanol and Ca2+/Sr2+ substitution leads to the stabilization of a so far not described S3 intermediate (S3') in a significant fraction of PSII centers. Untreated PSII resolves the same intermediate, but at much lower concentration. These observations demonstrate that water binding is not necessary for cofactor oxidation. Instead, it is cofactor oxidation that initiates water binding during the S2 → S3 transition.

Results and Discussion

A Modified S3 EPR Signal Is Observed upon Methanol Addition and in PSII in Which Ca2+ Is Biosynthetically Exchanged by Sr2+.

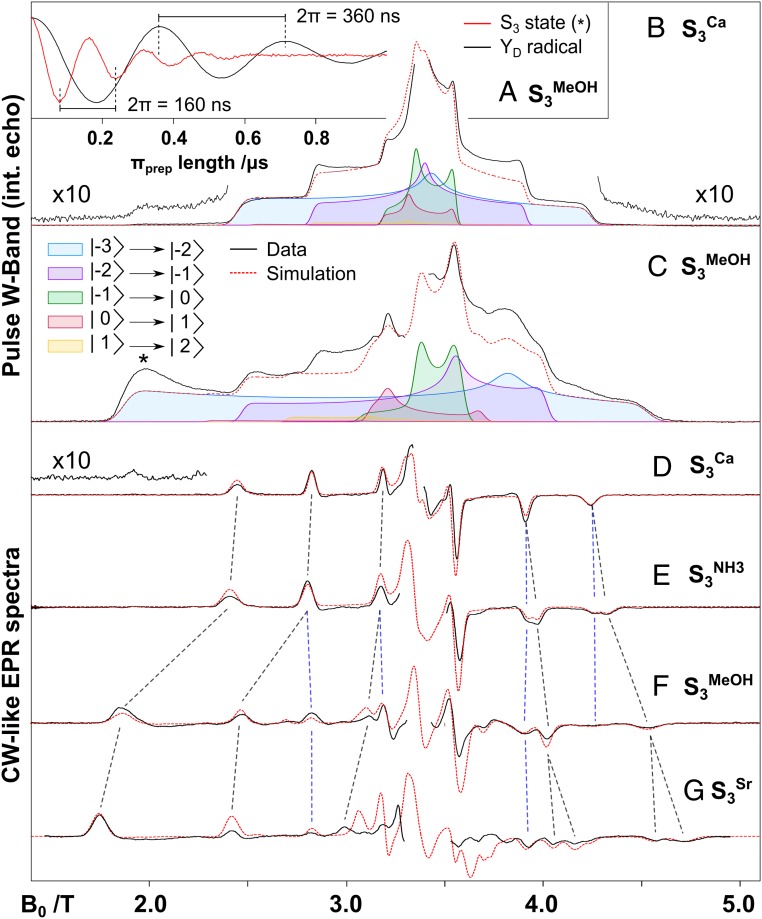

Fig. 3 shows the frozen solution W-band pulse EPR S3 state spectrum of the untreated PSII core preparations of Thermosynechococcus elongatus (16) and the 3 modified samples studied here. EPR measurements were performed on the preceding S2 state to check the integrity of all samples (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The S3 spectrum of all samples is centered at approximately g ≈ 2 (3.4 T) and falls within the 1.5- to 5-T magnetic field range. All spectra shown are obtained by subtracting the background spectrum of dark-adapted PSII (S1 state) from the spectrum collected after 2 flashes (S3 state), (SI Appendix, Figs. S2–S7). Throughout the text we refer to the S3 state measured in different PSII samples as follows: S3Ca, untreated PSII; S3Sr, biosynthetically exchanged Ca2+/Sr2+ PSII; S3MeOH, PSII with 3% vol/vol methanol (MeOH) added; and S3NH3, PSII with 100 mM ammonium chloride added, giving a concentration of 2 mM ammonia (NH3) in solution at pH 7.5. The S3NH3 spectrum is almost identical to the untreated S3 state spectrum (S3Ca). By taking the pseudomodulated transform of the absorption spectrum, it can more clearly be observed that the spectrum is made up of 2 signals: one identical to the untreated form and a second that is 10 mT broader (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Both fractions have approximately equal intensity, suggesting that NH3 is only bound in 50% of centers and thus its binding affinity decreases upon S3 formation. In any case, NH3 binding to the cofactor has only a very small effect on its electronic structure, suggesting ammonia does not interfere with S3 state progression. This is consistent with mass spectrometry measurements that show that the addition of NH3 does not strongly alter substrate exchange kinetics in the S3 state (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). We suspect that NH3 weakly binds at the same location as in the S2 state and that the 2 populations (NH3 bound and untreated) are in equilibrium and readily interconvert via W1/NH3 exchange. In contrast to the S3NH3 spectrum, both the S3MeOH spectrum and the S3Sr spectrum are strongly perturbed. Both spectra are significantly broader than the untreated one (2.5 T vs. 1.5 T), with the S3Sr spectrum being the broadest, but displaying an overall similar profile. In both the S3MeOH and S3Sr spectrum, there is a contribution of the S3Ca spectrum of about 20%. For the S3MeOH spectrum, this fraction cannot be completely removed but is further suppressed if the methanol concentration is increased from 3 to 5% vol/vol (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Upon close inspection it is observed that the S3MeOH–like spectrum is also present in samples without methanol (S3Ca), as judged by the low field turning point at 1.9 T. This “methanol-like” population also increases with increasing concentrations of the cryoprotectant glycerol to up to 20% (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Glycerol is a larger molecule, which has no direct access to the cofactor. This result, and the observation that the S3MeOH and S3Sr spectra are essentially the same, suggests that it is not a specific molecular interaction that leads to the perturbed S3 spectrum, but instead that these modifications somehow alter the protein-cofactor interface.

Fig. 3.

(A) Microwave nutation curves measured for the modified S3 state (S3MeOH) EPR spectrum compared with the nutation of the YD˙ signal (in black) assigns the spin value to S = 3. (B–G) W band EPR spectra of the S3 state measured for untreated (S3Ca), ammonia-treated (S3NH3), methanol-treated (S3MeOH), and Sr2+-substituted (S3Sr) PSII. All data (black lines) represent light-minus-dark difference spectra between samples poised in the S3 state and poised in the S1 state (SI Appendix, Figs. S2–S7). Data represent echo detected absorption spectra (B and C), and processed (pseudomodulated) echo detected spectra (D–G). Simulations (red dashed lines) of absorption spectra (B and C) include only the dominant species, while simulations of the pseudomodulated spectra (D–G) include all contributing species (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). A decomposition of the absorption spectra simulations according to individual transitions are also shown (see color code). Simulation parameters are listed in the SI Appendix, Table S1. The asterisk indicates the magnetic field position where the microwave nutation was performed. Experimental parameters are listed in SI Appendix.

Spin Hamiltonian Analysis of All S3-State Spectra.

The S3-state EPR signal seen for all sample types can be easily understood. The unpaired electron spins of the 4 Mn ions, which make up the cofactor, couple together by electron spin exchange. These interactions are much larger in energy than the microwave quantum and, as such, the EPR experiment only accesses the lowest energy state, which can be described in terms of a single effective spin state. In this instance, the Mn ions must predominately interact in a ferromagnetic fashion, leading to an effective spin state which has multiple unpaired electrons (high spin). Such a spin system gives rise to multiple EPR transitions, explaining the complexity of the signal profile observed. The degeneracy of the set of EPR transitions is lifted by the fine-structure interaction (D, E), which arises from the dipolar interactions of the unpaired electrons. Thus, these zero-field splitting parameters describe the width and overall shape of the spectrum (SI Appendix, Fig. S9).

The effective ground spin state (S) of all S3 state forms can be determined by a microwave nutation experiment (SI Appendix, Fig. 3A). In this experiment, an additional preparation pulse of variable length is applied before the detection sequence, causing the signal’s intensity to oscillate. The period of this oscillation decreases as the spin state increases. The nutation curve of the background tyrosine YD˙ radical signal (S = 1/2) is used as an internal reference. The period of oscillation for all S3 forms is approximately the same, consistent with a total spin state of S = 3 (SI Appendix), implying that the electronic connectivity of the 4 Mn ions is similar for all S3 isoforms (αααβ).

Simulations of all EPR spectra were performed using the spin Hamiltonian formalism assuming an S = 3 ground spin state. Fitted parameters are listed in SI Appendix, Table S1 and Fig. S11). The width of the spectrum scales with the magnitude of |D| whereas the symmetry of the spectrum instead is determined by the ratio of E to D (E/D); a large E/D (0.3) yields the most symmetric profile at about g ≈ 2, whereas a small E/D value leads to a contraction of the high field edge. Thus, the S3Ca and S3NH3 simulations yield a smaller |D| than the S3MeOH and S3Sr simulations. The opposite is true for the E/D value which is larger for S3Ca and S3NH3 compared with S3MeOH and S3Sr. The simulations shown are decomposed into sets of EPR transitions. Importantly, at the 2 edges of the spectrum (1.9 and 4.4 T), there is only one EPR transition, |−3> → |−2>. In subsequent double resonance experiments, it is thus convenient to perform measurements at these field positions.

The Magnitude of D as a Marker for the Coordination Number of the Mn Ions.

The fitted spin Hamiltonian parameter D is made up of weighted contributions of the site fine structure interaction (di) of each Mn ion, with the weighting factors (spin projection factors, ρi) determined by the spin exchange interactions between the Mn sites (SI Appendix, Eqs. S9 and S13). The local di values themselves come about from the interaction of unpaired electrons within the d shell of each ion, which couple via spin-spin and spin-orbit type mechanisms. Importantly, the magnitude of d can be used as a fingerprint for the oxidation state and ligand field of the metal ion. For example, octahedral MnIV complexes display small d values (<0.3 cm−1) owing to the nearly spherical distribution of the electrons in the half-filled t2g set of d orbitals. In contrast, Jahn-Teller active, octahedral MnIII complexes, or MnIV complexes with distorted ligand fields, have much larger d values of the order of 2 cm−1 (ref. 44 and refs. therein). Thus, a complex which contains only octahedral MnIV ions should display a small net D value, as the contribution of each Mn ion is small, whereas a complex which contains a MnIII ion or a distorted MnIV ion (i.e., 5 coordinate MnIV) should display a comparatively larger D value. Based on this simple observation, we previously noted that the small D value measured for the untreated S3 state indicated that the cofactor consists of only octahedral MnIV ions (16). Biomimetic Mn3O4Ca cubane models, which contain only octahedral MnIV ions (45), were used as a reference point. As the cofactor in the preceding S2 state does contain a 5-coordinate Mn (44), this observation requires the insertion of a water molecule into the cluster during the S2 → S3 transition. Following this logic, the larger D seen in modified PSII (S3MeOH, S3Sr) centers suggest that in these samples a population of the cofactor still contains a 5-coordinate Mn ion. Thus, in a significant population of modified PSII samples (S3MeOH, S3Sr), no water binding event takes place during the S2 → S3 transition.

A more quantitative analysis of the magnitude of D can be made in support of the above hypothesis. To do this, it is important to note that D scales with the effective spin state (SI Appendix). As a rule of thumb, the measured D can be scaled by the following ratio to allow comparison of different systems:

| [1] |

The biomimetic Mn3IVO4Ca2 cubane model (45) mentioned above—an all octahedral MnIV complex—displays a small D similar to that seen for the untreated S3 state. The effective spin value of the complex is S = 9/2, and its D = |0.068| cm−1 (45). Using Eq. 1, we need to scale the measured D value by 12/5 to directly compare it to the S3 state, yielding a corrected D = |0.162| cm−1. This is almost identical to the D value measured for the S3Ca system (i.e., 0.175 cm−1, within 10%). The same comparison can be made to the preceding high-spin S2B state, which contains a 5 coordinate MnIII ion. Multifrequency EPR measurements have estimated the D value for the cofactor in this state to be |0.45| cm−1 (46). Using Eq. 1, we now need to scale the measured D value by 2/3 to directly compare it to the S3 state, yielding a corrected D = 0.3 cm−1 (SI Appendix). This value is now in very good agreement to that observed for the methanol-treated and Sr2+-substituted samples, suggesting that the cofactor retains its 5-coordinate Mn site, but now in the IV+ oxidation state, i.e., an S3' state.

Magnetic Double Resonance Experiments Provide Further Evidence for a 5-Coordinate MnIV ion in the S3 State Measured in Modified PSII.

The unpaired electrons of the cofactor, which give rise to the EPR spectrum, couple with the nuclear spin of the 4 55Mn nuclei via hyperfine interaction. This interaction can be monitored by double resonance techniques, such as electron-electron double resonance-detected NMR (EDNMR). The observed hyperfine coupling value (Ai) of each Mn nucleus is the product of the site hyperfine tensor (ai) weighted by the spin projection factor (ρi) associated with each Mn ion. Thus, as with D, the hyperfine interaction provides site information about the local oxidation state and coordination number of each Mn and how they are electronically connected. EDNMR is performed at fixed magnetic fields within the EPR spectrum. Because of this we can measure hyperfine interactions for specific EPR transitions that make up the whole EPR spectrum. Furthermore, as each field position describes a unique orientation of the cofactor relative to the laboratory frame, these measurements map out the hyperfine interactions in 3 dimensions (SI Appendix, Figs. S12–S17).

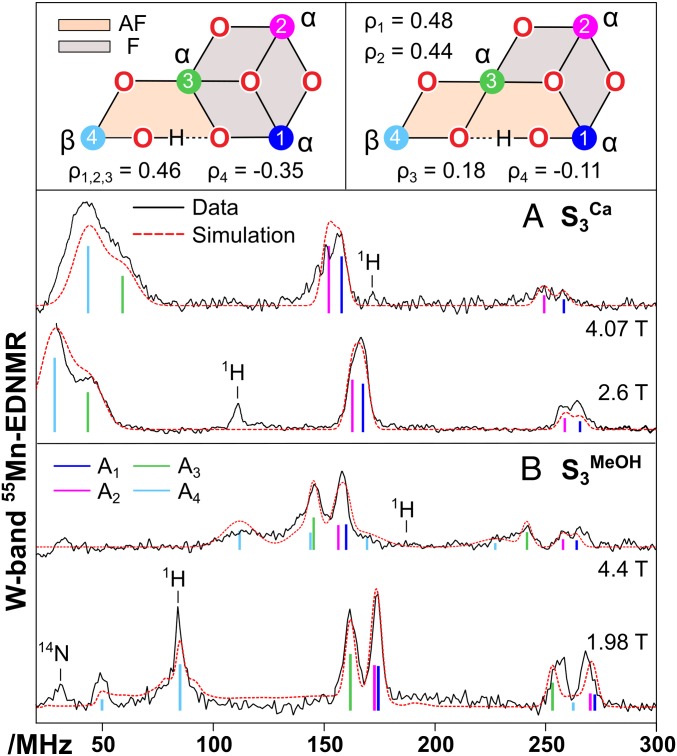

In our previous study of S3Ca, all peaks observed in 55Mn EDNMR spectra appeared in approximately the same position when measuring at different positions across the EPR spectrum. This result implied that all hyperfine interactions were independent of the orientation of the cofactor in the laboratory frame and, thus (Fig. 4A), the electronic environment of all 4 Mn ions is spherically symmetric, a property of octahedral MnIV ions (see above). This is not observed for the set of EDNMR spectra of the modified S3 state, with some lines strongly dependent on the field position at which they were measured (Fig. 4B). This provides further evidence that the modified S3 state forms contain a 5-coordinate MnIV ion. In addition, the set of EDNMR spectra of the modified S3 state do not resolve a peak at, or near, the 55Mn Larmor frequency, as seen for S3Ca. This result requires that all 4 Mn ions carry large spin projection factors, another deviation from that observed for the final S3 state, where the spin density was more unequally shared between the 4 Mn ions.

Fig. 4.

W band 55Mn-EDNMR spectra collected on the low and high field edge of untreated (S3Ca) (A) and methanol-treated (S3MeOH) (B) PSII (SI Appendix, Figs. S12–S17). Experimental data are shown as black lines; simulations as red dashed lines. A decomposition of the fitting into individual 55Mn nuclei (A1–A4) is also shown (see color code). Simulated and experimental parameters are listed in the SI Appendix, Table S2. Top Left side scheme explains the set of S3MeOH EDNMR spectra, whereas the Top Right scheme explains the set of S3Ca EDNMR spectra (16).

Constrained simulations of the set of modified S3 state EDNMR spectra described in SI Appendix support these observations (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). Four hyperfine tensors were needed to describe all spectral lines: 3 negative, near-isotropic tensors with one additional positive anisotropic tensor. As the magnitude of the site hyperfine interaction (ai) is expected to be similar for all 4 Mn ions, the fitting implies the 4 Mn ions carry 3 positive (α spin) and one negative (β spin) spin projection factors of similar magnitude consistent with EPR results. The same set of projection factors is observed for S2B (SI Appendix, Table S3), suggesting the overall structure of the S3' cofactor is similar to the S2B state (28).

The Nature of the S3' Intermediate.

The results presented above demonstrate that it is possible to advance to the S3 state without a water binding event, i.e., via an S3' intermediate. Importantly, this cofactor form, albeit at low concentration, is also seen in untreated samples, suggesting that it does represent a physiological intermediate. This result implies that cofactor oxidation is not triggered by water binding. Instead, it is the oxidation event that precedes water binding and, indeed, may be necessary for water binding. Thus, only pathway (B) and pathway (D) are consistent with experiment (Fig. 2). Of these, EPR data favor pathway (D) as the S3' intermediate resembles S2B. The observation that cofactor oxidation precedes water binding makes good chemical sense, as water binding in the S2 state would necessarily involve its binding on the Jahn–Teller axis of a MnIII ion, whereas water binding in the S3 state instead involves binding to a MnIV ion, a better Lewis acid. The results presented also imply that the S3' intermediate, under appropriate conditions, is long lived. This suggests that there are tunable thermodynamic and kinetic barriers to S2 → S3 progression. Within this framework, the effect of methanol and Ca2+/Sr2+ substitution can be understood. Methanol likely introduces a kinetic barrier to S-state progression, with its association with water molecules near the cofactor reducing the efficiency of water binding (40). We suspect a similar mechanism operates upon Ca2+/Sr2+ substitution (47). Interestingly, a recent report has shown that Ca2+/Sr2+ substitution alters the pKa values of the cofactors titratable ligands (W1, W2) (48). As water binding is likely coupled with either proton egression or an internal proton shift, perturbation of the proton network may also disrupt water binding (SI Appendix, Fig. S18).

Consequences for the Mechanism of O-O Bond Formation.

We stress that in all modified samples the untreated S3 cofactor signal was still observed (20% of centers). As such, we do not propose that the S3 state without water bound is able to directly progress to the transient [S4] state. Instead, as discussed above, we suggest that these perturbations alter the energy landscape between the final S3 state and its precursor (S3'), allowing us to trap the precursor state by freezing to cryogenic temperatures in a significant fraction of centers. At physiological temperatures these 2 forms are presumably in a dynamic equilibrium, suggesting the barrier for interconversion is small and tunable. Thus, delayed water binding is the most likely cause for the catalytic retardation and not perturbation of the transient [S4] state. These observations are in line with water exchange data, which show only modest changes between the S2 and S3 states, suggesting the bound substrate waters have a similar coordination in both states or at least can achieve a similar coordination via low barrier interconversion (11). In conclusion, our data show that the S2B state is an intermediate on the path to generating the S3' state, which has a similar structure as S2B, but where Mn4 is now a 5-coordinate MnIV ion. In unperturbed centers this S3B-type state quickly binds water to form the stable S3A state, which can proceed to [S4] following a further oxidation event.

Materials and Methods

PSII core complex preparations from T. elongatus were obtained as described earlier (49, 50). The S3-state was generated by 2 flashes using an Nd-YAG laser, and the samples were immediately frozen in liquid N2. EPR measurements at W band were performed using a Bruker ELEXSYS E680 at T = 4.8 K. Simulations of the EPR and EDNMR spectra were performed using the EasySpin package (51). See SI Appendix for further details.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support by the Max Planck Society and MANGAN project (Grant 03EK3545) funded by the Bundesministeriums für Bildung und Forschung, Australian Research Council Grant FT140100834, Vetenskaprådet Grant 2016-05183, Cluster of Excellence RESOLV (EXC 1069) funded by the German Research Council (DFG), the DFG research unit FOR2092 (NO 836/3-2) and Deutsch-Israelische Projektkooperation Grant LU 315/17-1 is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1817526116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Umena Y., Kawakami K., Shen J.-R., Kamiya N., Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9 Å. Nature 473, 55–60 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox N., Pantazis D. A., Neese F., Lubitz W., Biological water oxidation. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 1588–1596 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kok B., Forbush B., McGloin M., Cooperation of charges in photosynthetic O2 evolution-I. A linear four step mechanism. Photochem. Photobiol. 11, 457–475 (1970). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dau H., Haumann M., The manganese complex of photosystem II in its reaction cycle: Basic framework and possible realization at the atomic level. Coord. Chem. Rev. 252, 273–295 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hillier W., Messinger J., “Mechanism of photosynthetic oxygen production” in Photosystem II: The Light-Driven Water:Plastoquinone Oxidoreductase, Wydrzynski T., Satoh K., Eds. (Springer, 2005), vol. 1, pp. 285–305. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lohmiller T., et al. , The first state in the catalytic cycle of the water-oxidizing enzyme: Identification of a water-derived μ-hydroxo bridge. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 14412–14424 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suga M., et al. , Native structure of photosystem II at 1.95 Å resolution viewed by femtosecond X-ray pulses. Nature 517, 99–103 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kern J., et al. , Structures of the intermediates of Kok’s photosynthetic water oxidation clock. Nature 563, 421–425 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pérez Navarro M., et al. , Ammonia binding to the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II identifies the solvent-exchangeable oxygen bridge (μ-oxo) of the manganese tetramer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 15561–15566 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rapatskiy L., et al. , Detection of the water binding sites of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II using W-band 17O ELDOR-detected NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 16619–16634 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox N., Messinger J., Reflections on substrate water and dioxygen formation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1827, 1020–1030 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pérez-Navarro M., Neese F., Lubitz W., Pantazis D. A., Cox N., Recent developments in biological water oxidation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 31, 113–119 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pantazis D. A., Ames W., Cox N., Lubitz W., Neese F., Two interconvertible structures that explain the spectroscopic properties of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II in the S2 state. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51, 9935–9940 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegbahn P. E. M., Structures and energetics for O2 formation in photosystem II. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 1871–1880 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Isobe H., et al. , Theoretical illumination of water-inserted structures of the CaMn4O5 cluster in the S2 and S3 states of oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II: Full geometry optimizations by B3LYP hybrid density functional. Dalton Trans. 41, 13727–13740 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox N., et al. , Photosynthesis. Electronic structure of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II prior to O-O bond formation. Science 345, 804–808 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaharieva I., Dau H., Haumann M., Sequential and coupled proton and electron transfer events in the S2 → S3 transition of photosynthetic water oxidation revealed by time-resolved X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Biochemistry 55, 6996–7004 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaharieva I., et al. , Room-temperature energy-sampling Kβ X-ray emission spectroscopy of the Mn4Ca complex of photosynthesis reveals three manganese-centered oxidation steps and suggests a coordination change prior to O2 formation. Biochemistry 55, 4197–4211 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakamoto H., Shimizu T., Nagao R., Noguchi T., Monitoring the reaction process during the S2 → S3 transition in photosynthetic water oxidation using time-resolved infrared spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 2022–2029 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noguchi T., FTIR detection of water reactions in the oxygen-evolving centre of photosystem II. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 363, 1189–1194, discussion 1194–1195 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suga M., et al. , Light-induced structural changes and the site of O=O bond formation in PSII caught by XFEL. Nature 543, 131–135 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boussac A., Zimmermann J. L., Rutherford A. W., EPR signals from modified charge accumulation states of the oxygen evolving enzyme in Ca2+-deficient photosystem II. Biochemistry 28, 8984–8989 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yachandra V. K., Guiles R. D., Sauer K., Klein M. P., The state of manganese in the photosynthetic apparatus 5. The chloride effect in photosynthetic oxygen evolution–Is halide coordinated to the epr-active manganese in the O2-evolving complex–Studies of the substructure of the low-temperature multiline electron-paramagnetic-res signal. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 850, 333–342 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacLachlan D. J., Nugent J. H. A., Investigation of the S3 electron paramagnetic resonance signal from the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem 2: Effect of inhibition of oxygen evolution by acetate. Biochemistry 32, 9772–9780 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhn P., Eckert H., Eichler H. J., Renger G., Analysis of the P680•+ reduction pattern and its temperature dependence in oxygen-evolving PSII core complexes from a thermophilic cyanobacteria and higher plants. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 6, 4838–4843 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klauss A., Haumann M., Dau H., Alternating electron and proton transfer steps in photosynthetic water oxidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 16035–16040 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Narzi D., Bovi D., Guidoni L., Pathway for Mn-cluster oxidation by tyrosine-Z in the S2 state of photosystem II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 8723–8728 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Retegan M., et al. , A five-coordinate Mn(iv) intermediate in biological water oxidation: Spectroscopic signature and a pivot mechanism for water binding. Chem. Sci. 7, 72–84 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Debus R. J., Evidence from FTIR difference spectroscopy that D1-Asp61 influences the water reactions of the oxygen-evolving Mn4CaO5 cluster of photosystem II. Biochemistry 53, 2941–2955 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rivalta I., et al. , Structural-functional role of chloride in photosystem II. Biochemistry 50, 6312–6315 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siegbahn P. E. M., The S2 to S3 transition for water oxidation in PSII (photosystem II), revisited. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 22926–22931 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ugur I., Rutherford A. W., Kaila V. R. I., Redox-coupled substrate water reorganization in the active site of photosystem II-The role of calcium in substrate water delivery. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1857, 740–748 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Capone M., Narzi D., Bovi D., Guidoni L., Mechanism of water delivery to the active site of photosystem II along the S(2) to S(3) transition. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 592–596 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Askerka M., Wang J., Vinyard D. J., Brudvig G. W., Batista V. S., S3 state of the O2-evolving complex of photosystem II: Insights from QM/MM, EXAFS, and femtosecond X-ray diffraction. Biochemistry 55, 981–984 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Capone M., Bovi D., Narzi D., Guidoni L., Reorganization of substrate waters between the closed and open cubane conformers during the S2 to S3 transition in the oxygen evolving complex. Biochemistry 54, 6439–6442 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hammes-Schiffer S., Hydrogen tunneling and protein motion in enzyme reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 39, 93–100 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nöring B., Shevela D., Renger G., Messinger J., Effects of methanol on the Si-state transitions in photosynthetic water-splitting. Photosynth. Res. 98, 251–260 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandusky P. O., Yocum C. F., The mechanism of amine inhibition of the photosynthetic oxygen evolving complex–Amines displace functional chloride from a ligand site on manganese. FEBS Lett. 162, 339–343 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oyala P. H., et al. , Pulse electron paramagnetic resonance studies of the interaction of methanol with the S2 state of the Mn4O5Ca cluster of photosystem II. Biochemistry 53, 7914–7928 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Retegan M., Pantazis D. A., Interaction of methanol with the oxygen-evolving complex: Atomistic models, channel identification, species dependence, and mechanistic implications. Chem. Sci. 7, 6463–6476 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oyala P. H., Stich T. A., Debus R. J., Britt R. D., Ammonia binds to the dangler manganese of the photosystem II oxygen-evolving complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 8829–8837 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marchiori D. A., Oyala P. H., Debus R. J., Stich T. A., Britt R. D., Structural effects of ammonia binding to the Mn4CaO5 cluster of photosystem II. J. Phys. Chem. B 122, 1588–1599 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su J. H., et al. , The electronic structures of the S(2) states of the oxygen-evolving complexes of photosystem II in plants and cyanobacteria in the presence and absence of methanol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1807, 829–840 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cox N., et al. , Effect of Ca2+/Sr2+ substitution on the electronic structure of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II: A combined multifrequency EPR, 55Mn-ENDOR, and DFT study of the S2 state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 3635–3648 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mukherjee S., et al. , Synthetic model of the asymmetric [Mn3CaO4] cubane core of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 2257–2262 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haddy A., Lakshmi K. V., Brudvig G. W., Frank H. A., Q-band EPR of the S2 state of photosystem II confirms an S = 5/2 origin of the X-band g = 4.1 signal. Biophys. J. 87, 2885–2896 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pitari F., Bovi D., Narzi D., Guidoni L., Characterization of the Sr(2+)- and Cd(2+)-substituted oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II by quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics calculations. Biochemistry 54, 5959–5968 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boussac A., et al. , The low spin - high spin equilibrium in the S2-state of the water oxidizing enzyme. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1859, 342–356 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sugiura M., Inoue Y., Highly purified thermo-stable oxygen-evolving photosystem II core complex from the thermophilic cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus having His-tagged CP43. Plant Cell Physiol. 40, 1219–1231 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boussac A., et al. , Biosynthetic Ca2+/Sr2+ exchange in the photosystem II oxygen-evolving enzyme of Thermosynechococcus elongatus. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 22809–22819 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stoll S., Schweiger A., EasySpin, a comprehensive software package for spectral simulation and analysis in EPR. J. Magn. Reson. 178, 42–55 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.