Abstract

Neutrophil migration across tissue barriers to the site of injury involves integration of complex danger signals and is critical for host survival. Numerous studies demonstrate that these environmental signals fundamentally alter the responses of extravasated or “primed” neutrophils. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1 (TREM-1) plays a central role in modulating inflammatory signaling and neutrophil migration into the alveolar airspace. Using a genetic approach, we examined the role of TREM-1 in extravasated neutrophil function. Neutrophil migration in response to chemoattractants is dependent upon multiple factors, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated either extracellularly by epithelial cells or intracellularly by NADPH oxidase (NOX). We, therefore, questioned whether ROS were responsible for TREM-1-mediated regulation of migration. Thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal neutrophils isolated from wild-type (WT) andTREM-1-deficient mice were stimulated with soluble and particulate agonists. Using electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, we demonstrated that NOX2-dependent superoxide production is impaired in TREM-1-deficient neutrophils. Consistent with these findings, we confirmed with Clark electrode thatTREM-1-deficient neutrophils consume less oxygen. Next, we demonstrated that TREM-1 deficient neutrophils have impaired directional migration to fMLP and zymosan-activated serum as compared to WT neutrophils and that deletion or inhibition of NOX2 in WT but notTREM-1-deficient neutrophils significantly impaired direction sensing. Finally, TREM-1 deficiency resulted in decreased protein kinase B (AKT) activation. Thus, TREM-1 regulates neutrophil migratory properties, in part, by promoting AKT activation and NOX2-dependent superoxide production. These findings provide the first mechanistic evidence as to howTREM-1 regulates neutrophil migration.

Keywords: neutrophils, granulocytes, NADPH oxidative, signaling cascade, cell adhesion/recruitment/emigration, immune response, inflammation, innate cell mediated immunity, manipulation of immune response

1 |. INTRODUCTION

An essential early feature of a robust immune response to injury or infection is the ability of peripheral neutrophils to infiltrate tissues and cross epithelial barriers. These cells are recruited by chemokines secreted by the host and/or microbial agents that “prime” the neutrophil for subsequent action. Neutrophils possess diverse tools, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) intermediates, antimicrobial peptides, neutrophil extracellular traps, and numerous pattern recognition receptors, that facilitate the response to danger signals.1,2 Moreover these infiltrating neutrophils regulate the subsequent immune response by participating in B cell maturation, antigen presentation, Th17 responses, dendritic cell maturations, and Natural Killer Cell responses.3

In order to respond to a diverse array of danger signals, neutrophils express a broad selection of genetically encoded receptors.4,5 These receptors are grouped into families that include G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR), which recognize bacterial products and complement factors, Fc receptors, which recognize opsonized particles or organisms, adhesion receptors, cytokine receptors, and innate immune receptors including pathogen-associated molecular pattern receptors such as TLRs and NOD-like receptors (NLRs).6 In addition, neutrophils also express activating receptors of the immunoglobulin superfamily such as triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (TREM-1).7–9 TREM-1, initially discovered on human neutrophils and monocytes, serves as a critical amplifier of immune signaling.7 It synergizes with TLRs, NLRs, and damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) to increase inflammation.9–12 Bacterial products enhance TREM-1 expression on leucocytes10 and in multiple animal models of sepsis, blockade of TREM-1 signaling is protective.10,13,14 In humans, the presence of soluble TREM-1 in bronchoalveolar fluid and serum is associated with pneumonia15 and sepsis.10 Moreover, high levels of circulating soluble TREM-1 are associated with increased mortality suggesting that modulation of this global regulator of neutrophil function may be a therapeutic tool.16–19 In a previous study, we identified a novel role for TREM-1 in transepithelial migration of neutrophils to the alveolar air space and proposed that this is another means by which TREM-1 participates in the inflammatory host response to infection.20

ROS are known mediators of inflammatory signals and in neutrophils, they also serve as powerful bactericidal agents.21,22 In addition, ROS play an important role in neutrophil chemotaxis.23–27 Both exogenous and endogenous sources of ROS have been implicated in neutrophil migration. In vivo data demonstrate that epithelial dual oxidase (DUOX) generated an extracellular gradient of hydrogen peroxide at the wound margin in zebra fish larvae that correlated in a spatiotemporal manner with neutrophil recruitment.25 Knockdown of DUOX attenuated hydrogen peroxide production and concomitantly alleviated neutrophilic tissue infiltration. Using small-molecule functional screening in vitro, Hattori et al. identified NADPH oxidase (NOX)-derived ROS within neutrophils as a key regulator of neutrophil chemotaxis.23

Using a genetic model of TREM-1 deficiency, we investigate whether TREM-1 participates in the respiratory burst and directional migration of extravasated neutrophils in response to chemotactic agents. Herein, we demonstrate using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) that TREM-1 promotes NOX2-dependent superoxide release following stimulation with soluble and particulate agonists. We identify a NOX-dependent defect in directional motility in TREM-1-deficient neutrophils. Moreover, we observed decreased phosphorylation of protein kinase B (AKT) in TREM-1-deficient neutrophils. Based on these findings, we propose that TREM-1 modulates superoxide production in an AKT-dependent manner, which ultimately regulates neutrophil chemotaxis. These findings extend our earlier observations and provide 1 mechanism by which TREM-1 modulates the host immune response.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Generation of TREM-1- and CYBB-deficient mice

TREM-1-deficient mice were generated as previously described.20 The goal of these studies was to examine TREM-1 function in humans using a mouse model of TREM-1 deficiency. In mice, the Trem1 gene is adjacent to a highly homologous gene, Trem3, which likely arose from a duplication event. The 2 receptors have similar cellular distribution and associate with DAP12. Further suggesting that these 2 proteins have redundant functions in the mouse, functional studies in our laboratory and others show that both molecules are amplifiers of inflammatory signaling.20,28 In contrast, Trem3 is a pseudogene in humans, and therefore no functional overlap exists. Thus, to model the effect of blocking TREM-1 in humans, we generated a TREM-1-deficient mouse. All WT and knockout mice were bred in the barrier facility at the University of Iowa per the requirements of the National Institutes of Health Committee on Care. All animal protocols were reviewed and specifically approved by the University of Iowa Animal Care and Use Committee. Age- and sex-matched mice less than 150 days of age were selected for the experiments described herein.

CYBB deficient mice, lacking gp91phox, on a C57BL/6 background (gift from Sanjana Dayal University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA)29 and TREM-1 deficient mice, on a C56BL/6 background, were used in the generation of a double knockout mouse. Cybb is an X-linked gene, presenting complications in breeding animals for a double knockout mouse. The following strategy was used. Trem1/3−/− male mice were crossed with Cybb+/− females to generate Trem1/3+/−/Cybb−/y males, or Trem1/3+/−/Cybb+/− females. The offspring were then crossed to generate Trem1/3−/−/Cybb−/− females or Trem1/3−/−/Cybb−/y males and littermate Trem1/3+/+/Cybb+/+ females or Trem1/3+/+/Cybb+/y males. In the third and following generations, homozygous and/or heterozygous mice were crossed to produce closely related or littermate mice for use in experiments. Genotypes were determined by PCR for both Trem1/3 and Cybb and confirmed by FACs analysis of blood for TREM-1, using anti-mouse TREM-1, clone 174031 (R&D Systems), and dihydrorhodamine (DHR; Thermofisher Scientific) for ROS production with PMA (Sigma) stimulation.

2.2 |. Peritoneal neutrophil and macrophage isolation

Mice were intraperitoneally injected with 1 ml of sterile 4% thioglycollate (Fluka) and 16–18 h later peritoneal lavages were performed with 10 ml/mouse of phenol red-free HBSS without Ca2+/Mg2+ (HBSS−/−). The peritoneal exudate was hemolyzed, washed with phenol red-free HBSS−/−, filtered through 70 μM mesh filter, and held on ice until experimentation.30 The medium was switched to HBSS with Ca2+/Mg2+ (HBSS+/+) just before incubation with agonists. Similar numbers of neutrophils were isolated from WT and TREM-1-deficient mice, though there was a trend for decreased yield in TREM-1-deficient mice. Neutrophil purity in the lavages ranged between 78–80% as assessed by FACS analysis of lymphocyte antigen 6 complex locus G6D expression. Experiments were performed on pooled cells (3–5 mice per group). Male and female mice were equally represented.

Peritoneal macrophages were isolated 3.5 days after intraperitoneal administration of 1 ml of 4% thioglycollate. Lavage of the peritoneal cavity was performed as above and the cells were hemolyzed, washed with phenol red-free HBSS−/−, filtered through 70 μM mesh filter, and plated on 10 cm dishes or 6-well plates at a density of 1 million/ml. After the cells had adhered, the medium was switched to HBSS+/+ and opsonized zymosan (OpZ) was added at 2 different multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 15 and 35. Fifteen minutes later, monolayers were washed with HBSS−/− and cells scraped into lysis buffer and immunoblotted for phosphorylated and total AKT as described below. Macrophage purity was deemed to be >90% as determined by cytospin and HEMA3 (Fisher Scientific) staining.

2.3 |. Opsonized zymosan and zymosan-activated serum

Mouse blood collected without anticoagulant was allowed to clot for 30 min at 37°C. After centrifugation, the serum was aspirated and mixed with sonicated zymosan A (from Saccharomyces cerevisiae) (Sigma) particles in 3:1 v/v ratio. The suspension was mixed and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Following centrifugation, the supernatant was separated from the pellet and used as zymosan-activated serum (ZAS) after diluting to the requisite final concentration with HBSS+/+. The pellet containing opsonized zymosan (OpZ) was washed once with 500 μl phenol-red-free HBSS−/− and then resuspended in HBSS+/+ buffer to the original volume of the non-OpZ particle suspension to yield 1 × 106 particles/μl. Neutrophils were stimulated with OpZ at an MOI of 15:1.

2.4 |. Oxygen consumption rate

The rate of cellular oxygen uptake was monitored as previously described using an ESA BioStat multielectrode system (Clark Electrode) (ESA Products, Dionex Corp., Chelmsford, MA, USA) in conjunction with a YSI oxygen probe (5331) and glass reaction chamber vials in a YSI bath assembly (5301) (Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH, USA), all at 37°C. Cells were suspended in HBSS+/+ at a density of 2 × 106 cells/ml in total of 3 ml. Baseline oxygen consumption was monitored for about 5–10 min and for an additional time of up to 30 min following addition of 30 μL OpZ to stimulate the cells. Raw amperometric data were imported into Excel to calculate slopes representing oxygen consumption rate (OCR), which is expressed in units of attomoles O2 cell−1 s−1.

2.5 |. Mitochondrial volume, morphology, and respiration

Mitochondrial volume and morphology were examined by labeling cells with the mitochondrial fluorescent probe, MitoTracker Orange CMTMRos (ThermoFisher Scientific). Peritoneal neutrophils in suspension were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with 100 nM MitoTracker Orange and fixed and counterstained with 1 μg/ml DAPI. They were mounted on glass slides and examined using Leica SP8 confocal microscope. Images were captured as a Z-stack with a 40× oil lens and 5× zoom. Images were deconvolved using SVI’s Huygens Professional software and then analyzed with Imaris software. Two to 3 fields per slide and 3 mice per genotype were examined. The surface application tool was used to measure the mitochondrial volume and morphology. To verify that there was no difference between WT and TREM-1-deficient cells in uptake and retention of the probe, cells were incubated in suspension, as described above, with MitoTracker Orange, washed and geometric mean fluorescence estimated by FACS.

Cellular oxygen utilization extracellular acidification rates were determined using a Seahorse Bioscience XF96 extracellular flux analyzer (Agilent-Seahorse, North Billerica, MA, USA). Briefly, 50 μL of neutrophils suspended at 8 × 105 cells/ml in DMEM containing 25 mM Glucose (Sigma), 2 mM GlutaMAX™ (Life Technologies), and 1 mM Sodium Pyruvate (Life Technologies), pH 7.40 and with a known buffer capacity were placed into Cell-Tak™ (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA) cell and tissue adhesive-treated XF96 V3 PET microculture plates (Agilent-Seahorse). The cells were then adhered to the bottom of the plates after a brief spin in a centrifuge following manufactures’ recommendations. Additional media was then added to each well to a final volume of 175 μl. Experiments were performed following standard Seahorse Biosciences protocols. The final concentrations of mitochondrial inhibitors used were 2.5 μM Oligomycin A (Sigma), 300 nM carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP; Sigma), and 10 μM each of Rotenone (Sigma) and Antimycin A (Sigma). OCR was determined using standard approaches for this technology.31

2.6 |. Superoxide release using lucigenin

fMLP-induced superoxide was measured using the chemiluminescent probe, lucigenin, as described previously.32 Freshly isolated peritoneal neutrophils were added to a white 96-well plate (Wallac) (200,000 cells/well) in 180 μl of HBSS+/+ supplemented with 0.1% HSA (Sigma) and 10 μM lucigenin (Sigma) in the presence or absence of 20 μl/well of vehicle alone. fMLP was added 30 min into the reaction. The reaction was conducted for 60 min at 37°C and luminescence was measured every minute using the plate reader, FLUOstar Omega, equipped with an injection pump to deliver fMLP (BMG Labtech). Results are expressed as relative light units per well. Specificity of the signal was verified by including superoxide dismutase (SOD; Sigma; 100 U/well) in a parallel set of wells.

2.7 |. Superoxide detection using EPR spectroscopy

A total of 2 × 106 neutrophils were suspended in 1 ml HBSS+/+. The following reagents were sequentially added to the cell suspension: 5 μl of a 10 mM diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (Sigma) stock, 50 μl of a 1 M 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO; Dojindo Laboratories) stock, and 30 μl of OpZ (MOI of 15:1). The suspension was mixed gently and placed in a CO2-free incubator at 37°C. Multiple aliquots allowed for a new sample aliquot to be obtained and analyzed at 20 min intervals. Briefly, 1 ml of reaction mixture was placed in a quartz flat cell, which was then centered in a Bruker 4103 TM/8614 resonance structure and using a Bruker EMX EPR spectrometer.33 Spectra were obtained at room temperature (24–27°C). Typical EPR parameters were as follows: 3478 G center field; 80 G sweep width; 9.78 GHz microwave frequency; 20 mW power; receiver gain 1 × 105; modulation frequency of 100 kHz; modulation amplitude of 1.0 G; conversion time of 20.48 ms; and time constant of 81.928 ms with spectra collected in the additive mode with 4 sequential (Y Resolution) 10×-scans; each scan composed of a 1024 point spectrum. Spectral simulations of EPR spectra were performed using the WinSim program developed at the NIEHS as previously described.33 Peak heights were determined from spectra using tools available in the Bruker EMX software. Raw spectral data were processed by GraphPad Prism 7.

Specificity of the signal was verified by preincubating neutrophils with SOD (100 U/ml) or by using peritoneal neutrophils lacking gp91phox isolated from Cybb−/− mice.

2.8 |. Chemotaxis

Chemotaxis assays were performed using the EZ-TAXIScan™ system (Effector Cell Institute, Tokyo) as described by Volk et al.34 Migration toward fMLP and ZAS was determined in WT, Trem-1−/−, Cybb−/−, and Trem-1−/−/ Cybb−/− cells. Briefly, neutrophils were kept at a concentration of 10 × 106/ml in HBSS−/− and then diluted to 1 × 106/ml in EZT buffer (HBSS+/+ containing 0.1% HSA) just prior to use. About 10 μl of 1 × 106/ml cells were added to each of the 6 separate channels and aligned along the edge of the chamber. Breifly, 1 μl of 100 μM fMLP or 50% ZAS or vehicle was injected into the stimulus chamber and chemotactic gradient was allowed to form. In some experiments, cells were pre-incubated for 30 min with 50 μM of diphenyleneiodonium (DPI; Sigma) or 0.1% DMSO before addition to the chemotactic gradient. Data were recorded for 1 channel at a time with 1 s time lapse interval between channels. Chemotaxis assay images were captured for 60 min with an image collection rate of 3 frames/min for each of the 6 channels. Movies were analyzed using Image J software. Cells were manually tracked, and the percentage of motile cells from each experimental condition was calculated. The chemotactic index (CI) was calculated as the ratio of net path length toward the chemotactic agent to total path length. Average instantaneous velocity for individual cells was also assessed using Image J software, with xy-coordinates scaled for 1 μm in accordance with the manufacturer’s specifications. Chemotaxis parameters were computed using data obtained from individual cell tracks from at least 3 separate experiments, with at least 30 cells analyzed per condition.

2.9 |. Cell lysis and immunoblotting

Peritoneal exudate cells were collected from thioglycollate-stimulated WT and TREM-1/3-deficient mice and stimulated for increasing times up to 1 h with OpZ (MOI 15) or 0, 1, and 15 min with 100 μM fMLP in HBSS+/+. After incubation, cells were treated on ice for 20 min with 1.15 mM diisopropylfluorophosphate (Sigma) and collected by centrifugation for 5 min at 300 × g and washed in HBSS−/−. Cells were lysed with lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40 with protease and phosphatase inhibitors) and sonicated for 20 s at 20% amplitude. After clarification for 10 min at 16,100 × g, total protein in the lysate was determined by the DC Lowry method. Equivalent amounts of lysate were separated by SDS/PAGE under reducing conditions, transferred to PVDF membranes, stained with Ponceau S, blocked with 3% BSA, and immunoblotted overnight at 4°C with biotinylated antibodies to pAKT (Cell Signaling, Ser 473 #5012), AKT (Cell Signaling, pan #5373), phospho-p44/42 MAPK (pERK1/2) (Cell Signaling, Thr202/Tyr204 #14227), p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2) (Cell Signaling, #5013), p-38 MAPK (Cell Signaling #9212S), or phospho p38 MAPK (p-p38MAPK) (Santa Cruz Bitotechnology sc-166182). Membranes were washed and those that were incubated with biotinylated primary antibodies were exposed to streptavidin-HRP (Cell Signaling, #3999) and the rest were incubated with anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Cell Signaling, #7074) for 1 h at room temperature. HRP was detected with ECL 2 (ThermoFisher Scientific) and images were acquired digitally (FujiFilm, Fuji Medical Systems, USA) and on X-ray film. Densitometric analyses of bands were performed using Image J.

2.10 |. Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism. Differences between WT and TREM-1-deficient neutrophils were determined by Student’s t-test (Figs. 1A, 3B, 5D, and 6C, Supplementary Fig. 1), nonlinear regression analysis (Fig. 3A), one-way ANOVA (Figs. 4 and 5B, and C), two-way ANOVA (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 5), and Chi Square (Fig. 5A) analyses using GraphPad Prism statistical software. All data were expressed as Mean ± SEM and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

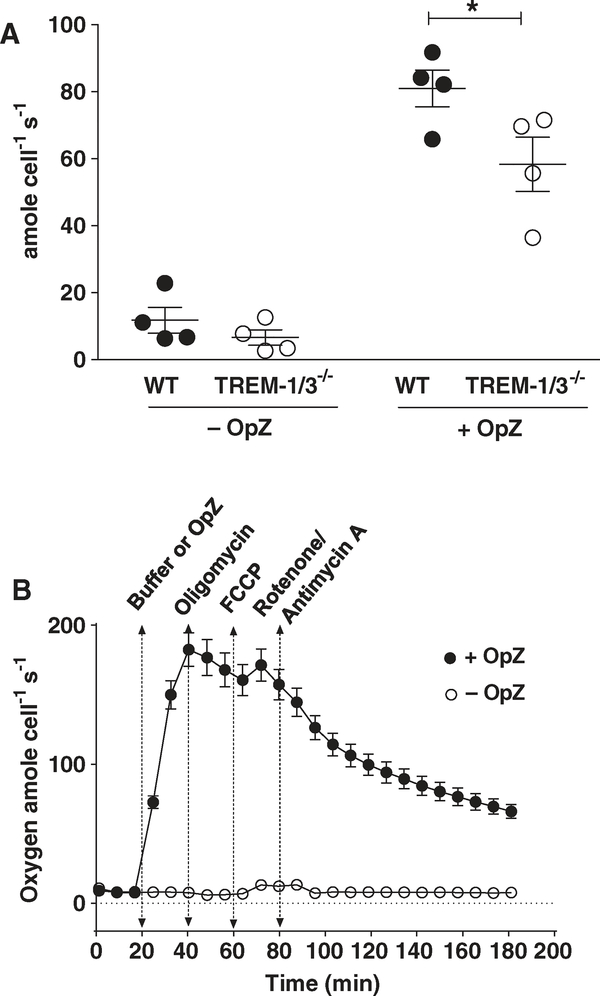

FIGURE 1. TREM-1 deficiency attenuates oxygen consumption independently of mitochondrial respiration.

(A) Oxygen consumption in WT and TREM-1-deficient neutrophils was determined using the Clark electrode. Data from 4 representative experiments are shown as Mean ± SEM of 3–5 pooled mice/data point. *P < 0.05. (B) Oxygen consumption using the SeaHorse Assay was not attenuated by mitochondrial inhibitors after OpZ stimulation. Data are expressed as Mean ± SEM of 7 replicates with each data point being representative of at least 3 pooled mice

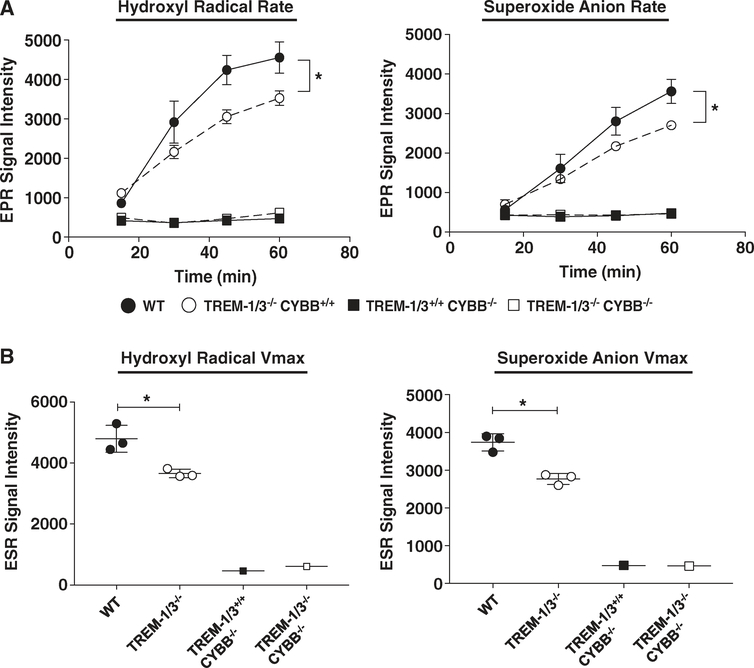

FIGURE 3. TREM-1 deficiency attenuates NOX2-derived superoxide in response to OpZ.

Rate (A) and maximal velocity (Vmax) (B) of superoxide and hydroxyl radical production in WT, Trem-1/3−/−, Cybb −/−, and Trem-1/3−/−/Cybb−/− neutrophils following OpZ stimulation. Data from 3 experiments were compiled and are shown as Mean ± SEM, 3–5 pooled mice/data point. *P < 0.05

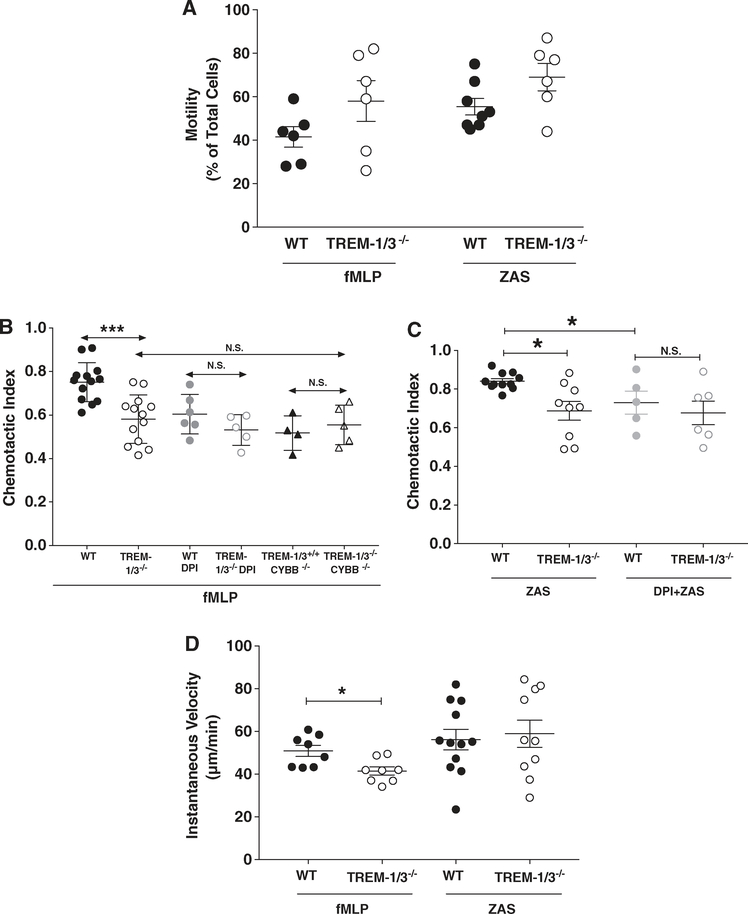

FIGURE 5. TREM-1 deficiency impairs neutrophil chemotaxis in a NOX2-dependent manner.

Migration using the EZ-TAXIScan device was determined in WT, TREM-1-deficient, CYBB-deficient, and TREM-1/CYBB-deficient neutrophils stimulated with fMLP or ZAS in the presence or absence of 10 μM DPI. Motility (A), CI (B and C), and instantaneous velocity (D) were measured. Data from 4–12 independent experiments were compiled and shown as Mean ± SEM; each data point represents 3–5 pooled mice. *P < 0.05

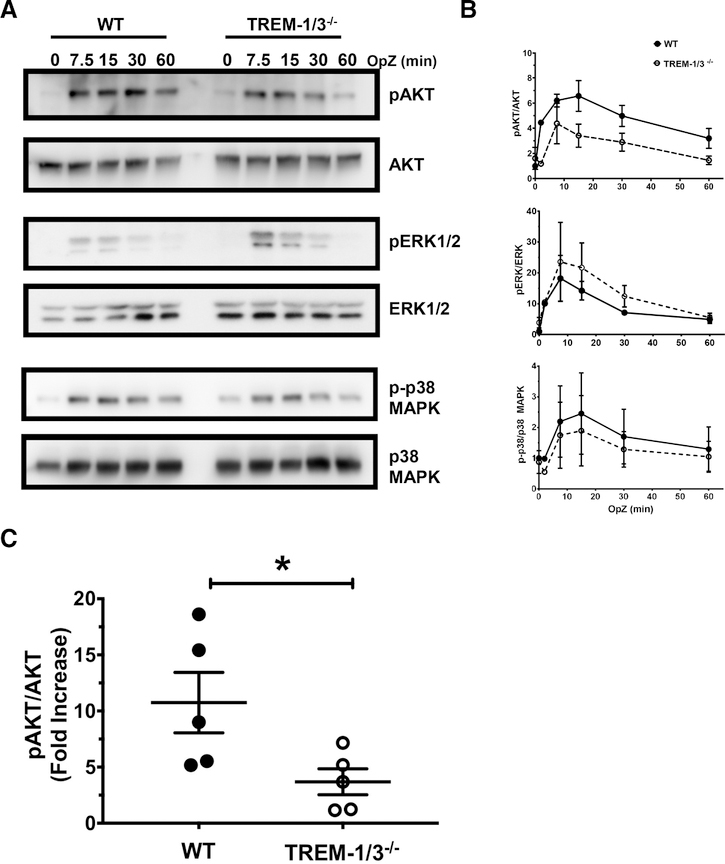

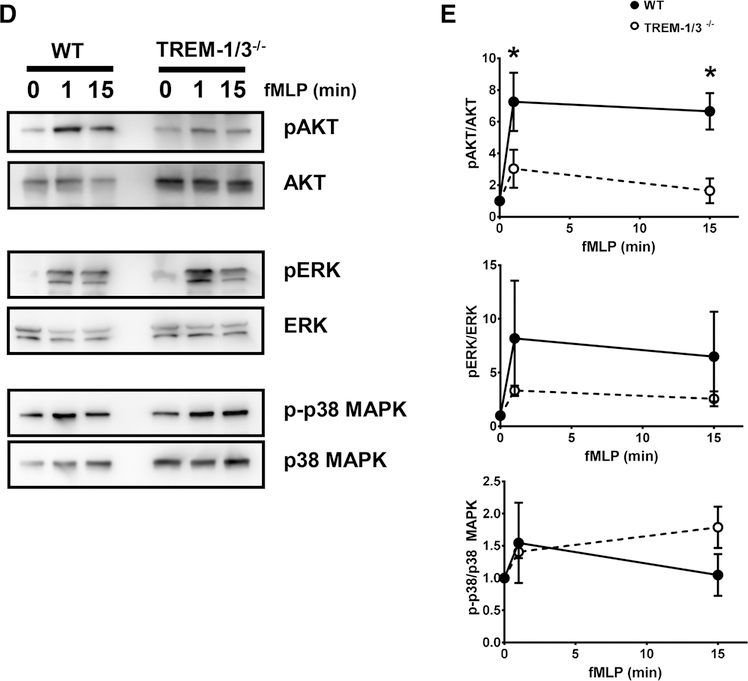

FIGURE 6. TREM-1 deficiency attenuates AKT activation.

WT and TREM-1-deficient neutrophils were stimulated for the indicated times with OpZ and the phosphorylation of AKT, ERK1/2, and p38MAPK was determined. (A) Immunoblots from 1 representative experiment out of 3 are shown. (B) Quantitation of phosphorylated and total kinase levels of all 3 time course experiments. (C) WT and TREM-1-deficient neutrophils were stimulated for 15 min with OpZ and AKT activation determined. Quantitation of phosphorylated and total AKT levels is shown as fold increase relative to resting levels. Each data point represents Mean ± SEM of 3–5 pooled mice, N = 5 independent experiments; *P < 0.05. (D) WT and TREM-1-deficient neutrophils were stimulated for the indicated times with 100 μM fMLP and the phosphorylation of AKT, ERK1/2, and p38MAPK was determined. Representative immunoblots from 1 out of 3 are shown. (E) Quantitation of phosphorylated and total kinase levels of all 3 time course experiments is shown as fold increase relative to resting levels. Each data point represents Mean ± SEM of 3–4 pooled mice, N = 3 independent experiments; *P < 0.05

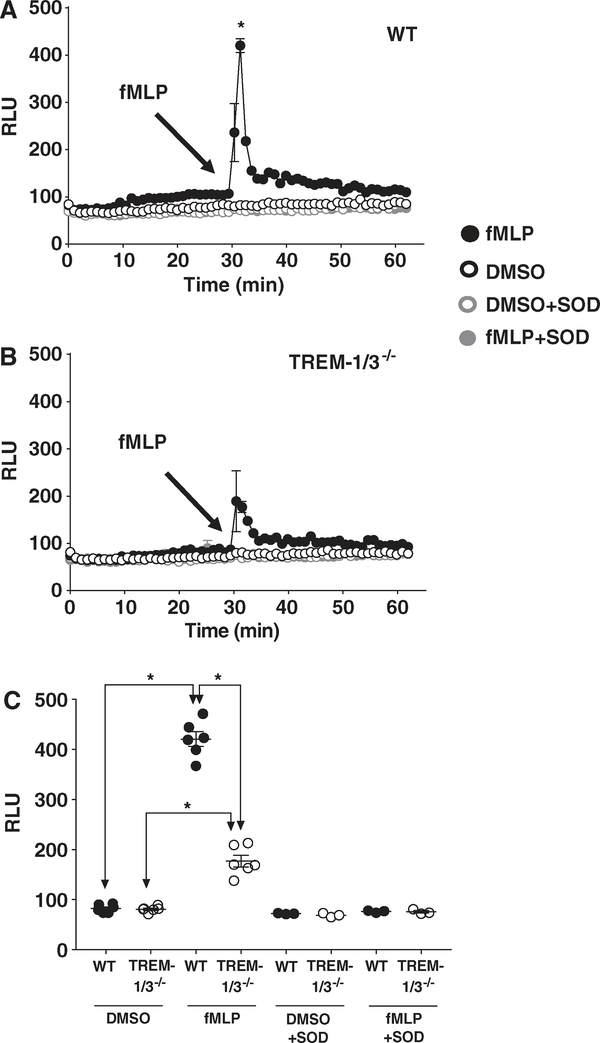

FIGURE 4. TREM-1 deficiency attenuates superoxide production in response to fMLP.

Superoxide generated by WT (A) and TREM-1-deficient (B) neutrophils stimulated with fMLP (100 μM) was determined using a chemiluminescent assay with lucigenin as described in “Methods” section. (C) Peak superoxide generation for each treatment. Mean ± SEM of relative light units of 6 replicates of 3–5 pooled mice. *P < 0.05

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. TREM-1 deficiency attenuates oxygen consumption independently of mitochondrial respiration

Previous investigations have shown that TREM-1 ligation induces ROS production in human neutrophils stimulated with soluble35,36 and particulate agonists.36 In these experiments, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate was used to measure ROS. As this probe detects multiple derivatives of superoxide, we wanted to investigate directly whether TREM-1 signaling regulated NOX2-dependent superoxide production. Moreover, because we had previously demonstrated that TREM-1 was required for neutrophil transepithelial migration, we were interested in examining ROS production specifically in mature, extravasated neutrophils. We, therefore, conducted all our studies of TREM-1 function in thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal neutrophils isolated from WT and TREM-1-deficient mice. In all experiments, peritoneal neutrophils were pooled from 3–5 mice per each group. As molecular oxygen is the precursor for all ROS, we first determined whether TREM-1 expression altered oxygen consumption. Using the Clark electrode, we measured oxygen consumption before and after stimulation with OpZ (Fig. 1A). Baseline oxygen consumption in resting cells was minimal and was not significantly different between WT and TREM-1-deficient neutrophils. Following OpZ stimulation, oxygen consumption increased dramatically over 30 min and was attenuated in TREM-1-deficient neutrophils compared to WT neutrophils. These results suggest that TREM-1 plays a role in the respiratory burst following phagocytosis.

In neutrophils, NOX2 is the major source of ROS. Before we determined the role of TREM-1 in NOX2-mediated superoxide production, we first ruled out mitochondria as a significant source of ROS in stimulated neutrophils. Mitochondrial respiration in WT and TREM-1-deficient peritoneal neutrophils was determined using the Seahorse assay to measure extracellular acidification rates in the presence or absence of the indicated mitochondrial inhibitors. Consistent with the above results, stimulation with OpZ increased oxygen consumption that peaked at 40 min and remained elevated despite inhibition of ATP synthesis with oligomycin (Fig. 1B). Uncoupling the electrochemical gradient with FCCP did not elevate the oxygen consumption as would be expected if mitochondria were a significant source of ROS. Moreover, the addition of rotenone and antimycin A, inhibitors of mitochondrial electron transport chain complex I and complex III, did not cause the characteristic steep decline in oxygen consumption. These results demonstrate that mitochondria have a negligible contribution to O2 consumption in stimulated neutrophils.

Mitochondrial volume and morphology in WT and TREM-1 deficient peritoneal neutrophils were analyzed using MitoTracker Orange. Analyses of the images revealed similar mitochondrial volume and shape (Supplementary Fig. 1A–C). No differences in the uptake and retention of the probe were observed between WT and TREM-1-deficient neutrophils as determined by FACS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1D).

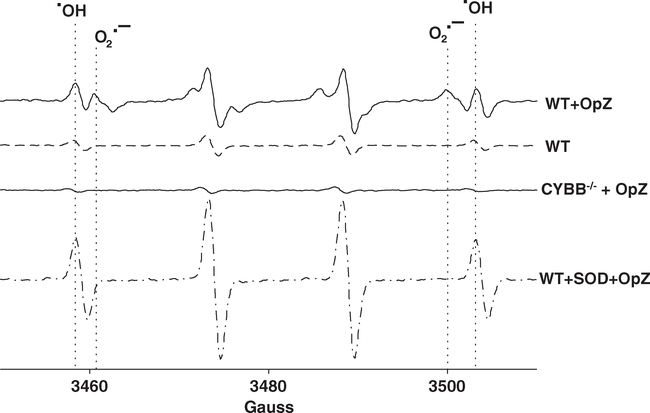

3.2 |. TREM-1 deficiency attenuates NOX2-derived superoxide in response to OpZ

To specifically measure superoxide production, we used EPR spectroscopy.37,38 The highly reactive hydroxyl radical (⋅OH) and superoxide anion (O2⋅−) were captured as DMPO adducts in the form of DMPO-OH and DMPO-OOH, respectively. Spectra of the radicals from WT neutrophils are shown (Fig. 2). Resting neutrophils showed a small ⋅OH peak that was higher than the ⋅OH peak in gp91phox deficient neutrophils suggesting a small degree of basal superoxide production that is rapidly oxidized to the ⋅OH radical. Following stimulation with OpZ, a particulate stimulus derived from the yeast cell wall, a second peak was observed that was abolished by pretreatment with SOD and is, therefore, consistent with the superoxide anion. SOD increased the ⋅OH signal consistent with the conversion of O2⋅− to hydrogen peroxide and subsequent partial oxidation to the ⋅OH radical. In addition, we isolated neutrophils from Cybb−/− mice, which lack functional NOX2 due to deletion of Cybb gene that encodes gp91phox (Cybb−/−). These neutrophils produce no detectable O2⋅− following OpZ stimulation further validating the identity of the O2⋅− peak.

FIGURE 2. EPR spectra of superoxide and hydroxyl radicals in resting and stimulated neutrophils.

Representative EPR spectra of resting and OpZ-stimulated WT neutrophils showing DMPO adducts of superoxide and hydroxyl radical peaks. Spectra from WT neutrophils preincubated with SOD and spectra from gp91phox-deficient neutrophils stimulated with OpZ

Next, we measured the rate and Vmax of phagocytic superoxide generation in WT and TREM-1-deficient peritoneal neutrophils that were isolated and pooled as described above. OpZ stimulated a rise in both ⋅OH and O2⋅− radicals that was linear during the first hour of stimulation (Fig. 3A and B) in both WT and TREM-1-deficient neutrophils. A significantly higher rate of ⋅OH radical and O2⋅− (Fig. 3A) production was evident in WT neutrophils compared to TREM-1-deficient neutrophils. Maximal ⋅OH and O2⋅− production were also significantly higher in WT than in TREM-1-deficient neutrophils (Fig. 3B).

To verify the source of superoxide production in extravasated neutrophils, we cross-bred Trem-1/3−/− with Cybb−/− mice to generate Trem-1/3+/+/Cybb+/+, Trem-1/3−/−/Cybb+/+, and Trem-1/3+/+/Cybb−/− and Trem-1/3−/−/Cybb−/− mice. Peritoneal neutrophils were isolated from 3–5 mice per group and analyzed using EPR. OpZ was unable to stimulate either O2⋅− or ⋅OH radicals in all gp91phox-deficient neutrophils regardless of the expression of TREM-1 (Fig. 3A and B). These results clearly indicate the requirement of functional NOX2 for superoxide production in stimulated neutrophils and that NOX2 accounts for TREM-1-mediated effects on superoxide production. Taken together, results from the above figures identify a role for TREM-1 in NOX2-dependent superoxide production.

3.3 |. TREM-1 deficiency attenuates superoxide production in response to fMLP

We next examined the role of TREM-1 in response to fMLP, known to be important in neutrophil chemotaxis. As our existing EPR spectroscopy instrumentation could not capture the rapid kinetic response to fMLP, we utilized the chemiluminescent probe, lucigenin. WT and TREM-1-deficient peritoneal neutrophils were isolated as described above and stimulated with 100 μM fMLP using a fluorometer fitted with an injection pump. Our results show that, compared to WT neutrophils, TREM-1-deficient neutrophils release significantly less superoxide in response to fMLP (Fig. 4A–C). Addition of SOD decreased fMLP-induced signal to resting levels confirming the specificity of the assay for superoxide. Thus, these data demonstrate that TREM-1 expression modulates superoxide production in response to soluble and particulate agonists in extravasated neutrophils.

3.4 |. TREM-1 deficiency impairs neutrophil chemotaxis in a NOX2-dependent manner

While the role of neutrophil ROS in direct pathogen killing is well described, recent data demonstrate ROS impact many other cell processes. ROS have been implicated in neutrophil migration and NOX-derived ROS are important for directional motility.23–27 Our previous observations demonstrate that TREM-1 plays an important role in transepithelial migration of neutrophils in the infected lung.20 We, therefore, questioned whether ROS mediated the effects of TREM-1 on neutrophil migration. Using the EZ-TAXIScan™ device, the migration of WT and TREM-1-deficient neutrophils was measured. Migratory parameters included percentage of total number of cells that migrated at least 10 μM in 30 min (motility), speed of migration (instantaneous velocity), and directionality of migration (CI) as detailed in “Methods” section and described previously.34 fMLP and ZAS were used as chemoattractants. The loading concentrations of the agonists were previously established to induce maximal migration (data not shown). In the absence of stimuli, cells remained at the starting point and did not migrate. There was no difference in motility between WT and TREM-1-deficient neutrophils in response to either fMLP or ZAS. (Fig. 5A). However, the motility parameter does not distinguish random from directional movement. CI measures directional migration. In response to either chemoattractant, WT neutrophils exhibited a significantly higher CI when compared to TREM-1-deficient neutrophils (Fig. 5B and C, Supplementary Figs. 2–4). To determine whether ROS was required for TREM-1-mediated neutrophil migration, we used 2 approaches to assess NOX2 activity. In 1 set of experiments, we preincubated WT and TREM-1-deficient neutrophils with DPI, a flavo-protein inhibitor of NOX2, before exposing them to the chemotactic gradient. CI of WT neutrophils in response to either fMLP or ZAS was significantly reduced in the presence of DPI to a level similar to TREM-1-deficient cells. Interestingly, DPI had no additional effect on TREM-1-deficient neutrophil CI suggesting that the impaired CI was due to TREM-1-mediated effects on NOX2. TREM-1 was not important for migratory speed in response to ZAS and only modestly important for fMLP as instantaneous velocity measured in WT was higher than TREM-1-deficient neutrophils (Fig. 5D).

To confirm results obtained with the pharmacological inhibitor, migration to the chemotactic agents was determined in neutrophils isolated from genetically modified mice either lacking functional NOX2 (Cybb−/−) or both TREM-1 and NOX2 (Trem-1/3−/−/Cybb−/−). As observed with DPI, CI in neutrophils from NOX2-deficient Cybb−/− mice was significantly reduced in comparison to WT (Fig. 5B). No difference was observed in CI between CYBB-deficient and TREM-1-deficient neutrophils. More importantly, the deletion of TREM-1 from NOX2-deficient neutrophils did not further decrease directional migration as the CI in CYBB-deficient neutrophils was not different from TREM-1/CYBB-deficient neutrophils. These results, therefore, strongly indicate that impaired chemotaxis observed in TREM-1-deficient neutrophils was entirely due to inhibition in NOX2-dependent superoxide production.

3.5 |. TREM-1 deficiency attenuates AKT activation

As the PI3K/AKT pathway is downstream of TREM-1 signaling8 and is implicated in NOX activation together with MAPK such as ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK,39 we next examined the role of TREM-1 in AKT and MAPK activation in peritoneal neutrophils. Neutrophils were stimulated with OpZ for 7.5, 15, 30, and 60 min or 0, 1, and 15 min with 100 μM of fMLP. Whole cell lysates were prepared, resolved by SDS/PAGE, and immunoblotted with antibodies directed to phosphorylated and total kinases. A representative gel from 1 out 3 identical experiments for each kinase is shown (Fig. 6A). Peak activation of AKT occurred 15 min after OpZ stimulation and in some experiments, sustained activation was observed up to 30 min (Fig. 6A and B). p38MAPK and ERK1/2 activation was observed earlier after 7.5 min of stimulation. TREM-1-deficient neutrophils showed decreased activation of AKT, as represented by lower phosphorylated/total kinase, compared to WT neutrophils (Fig. 6B and C). In contrast, levels of phosphorylated p38MAPK appeared to be unaffected by TREM-1 deletion and there was a tendency for higher ERK1/2 activation in TREM-1-deficient neutrophils. To confirm the effect of TREM-1 on AKT activation, we measured phosphorylated/total AKT levels in 5 independent experiments. OpZ-induced AKT activation was greater in WT compared to TREM-1-deficient neutrophils. (Fig. 6C).

As with OpZ, fMLP stimulation induced 2-fold (1 min) and 4-fold (15 min) greater AKT activation in WT cells compared to TREM-1-deficient neutrophils (Fig. 6D and E). In contrast, no significant differences were observed in ERK and p38MAK activation between WT and TREM-1-deficient neutrophils.

To assess whether TREM-1 plays a similar role in macrophages, we determined the effect of OpZ on AKT activation in peritoneal macrophages. Stimulation for 15 min at MOIs of 15 and 35 revealed no difference in AKT activation between WT and TREM-1-deficient macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that TREM-1 regulates neutrophil chemotaxis in a ROS-dependent manner and that the ROS is derived from NOX2-mediated superoxide production. It is likely that TREM-1 mediates these effects through the PI3K/AKT pathway. These findings represent the first mechanistic insight into how TREM-1 contributes to the regulation of neutrophil migration.

4 |. DISCUSSION

TREM-1 synergizes with TLRs, NLRs, and DAMPs to increase inflammation.10,20,40 The TREM-1 pathway modulates phagocytosis, respiratory burst, degranulation, and transepithelial migration.7,20,35,36 Thus, it is not surprising that TREM-1 is emerging as global regulator in many pathologic processes. Administration of TREM-1 antagonists improves survival in sepsis models while TREM-1 deficiency impairs survival.10,13,20 In models of hepatocellular carcinoma, inhibition of TREM-1 is protective.41 Finally, TREM-1 inhibition has also been shown to be protective in a murine model of cardiac infarction.42 Thus TREM-1 signaling appears to play a central role during infection, cancer, and ischemia.

Herein, we report that neutrophil respiratory burst mediated by TREM-1 is NOX-dependent and that it is significantly impaired in TREM-1-deficient neutrophils using EPR to specifically measure superoxide. Previous studies have reported increased ROS production following TREM-1 ligation in the presence or absence of LPS, GM-CSF, and particles.35,36 Our findings are also consistent with an earlier report demonstrating attenuated oxidative burst in TREM-1-silenced peritoneal neutrophils as measured by the fluorescent probe, DHR.14 A far greater inhibition in ROS was noted in response to opsonized Escherichia coli than what we observed with OpZ. However, it is worth noting that because different probes were used to detect ROS in these previous studies, and because specificity of the fluorescent signal was not established, a direct comparison cannot be made between our results and theirs.14,35,36

TREM-1 is composed of a long extracellular domain, a transmembrane region and a short cytoplasmic tail that associates with DAP 12 for signaling.8,43 Receptor ligation results in recruitment of Syk, which initiates the recruitment of PI3K, PLC, SLP-76-Vav, Grb2-Sos, and c-Cbl, which, in turn, trigger activation of AKT, Ca2+ influx, protein kinase C (PKC), active GTP-bound Rac, MAPK, and rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton.8,12 As many of the kinases activated downstream of TREM-1 ligation are also downstream of GPCR,6 such as fMLPR and complement receptor (CR), it is very likely that TREM-1 synergizes with these receptors by activating the same signaling molecules thereby amplifying responses. These kinases can phosphorylate p47phox and trigger translocation to the membrane.39,44 Our data support the role of PI3K/AKT pathway in TREM-1-mediated effects on superoxide production.

Another possible means by which TREM-1 can synergize with multiple receptors to integrate signaling is by colocalizing with them after neutrophil stimulation. Fortin et al. demonstrated colocalization of TREM-1 with TLR in lipid-enriched caveolar microdomains that are also known to segregate the multisubunit NOX complex as well as FcγR.35,45,46 Under resting conditions, the membrane components of NOX, gp91, and p22phox are already present in lipid rafts. Following ligation, receptors such as FcγR or CR are recruited to these microdomains together with PKC-δ and cytoplasmic NOX components to initiate superoxide production. Disruption of lipid rafts attenuates or delays the onset of superoxide generation in neutrophils.46–49 Thus, following ligation by fMLP, OpZ, or complement factors present in ZAS, GPCR, FcγR, and/or CR may be recruited to lipid rafts together with NOX and TREM-1 to promote superoxide production. Our results are consistent with the notion that TREM-1 is important for stabilizing a relationship with NOX and 1 or more of these receptors.

Localized production of NOX-dependent superoxide and/or its derivatives can impact key aspects of neutrophil motility and direction sensing.23,24,50 In fact, Hattori et al. observed localized expression of NOX at the leading edge of migrating neutrophils.23 Moreover neutrophils depleted of functional NOX by pharmacological inhibition and chronic granulomatous disease neutrophils display attenuated directional sensing. Our findings reveal a ~25% defect in directional migration in WT neutrophils preincubated with DPI or in NOX2-deficient neutrophils, which indicates that NOX-dependent superoxide contributes to the migratory process. Consistent with our findings, Hattori et al. also observe similar decreases in DPI-inhibited murine neutrophil chemotaxis.23 The important aspect of our findings is that NOX2 inhibition attenuates directional migration only in WT but not TREM-1-deficient neutrophils and that NOX2-inhibited WT cells have similar CI values as TREM-1-deficient neutrophils. Based on our findings, we reason that the ROS produced by TREM-1-dependent pathways promote migration in extravasated neutrophils. We did not examine the role of TREM-1 in the regulation of immature bone marrow-derived neutrophils and thus the role of TREM-1 in these cells is yet to be explored.

TREM-1-deficient neutrophils exhibit marked impairment in transepithelial migration both in vivo and in vitro.20 The differences in chemotaxis we report in the current study with TREM-1-deficient neutrophils are more modest. ROS is not the only determinant of neutrophil migration as exemplified by our findings. In fact, following fungal or bacterial infection, recruitment of NOX-deficient neutrophils to sites of infection remains intact in Cybb−/− and p47phox−/− mice.29,51–53 The in vivo milieu that extravasated neutrophils encounter is far more complex. EZ-TAXIScan assesses neutrophil migration to a single chemoattractant under well-controlled conditions. Thus, these assays do not reflect the multifaceted interactions between neutrophils and epithelial cells that have profound effects on transcellular passage. Transepithelial migration of neutrophils proceeds from the basolateral to the apical end of the monolayer and during the transit through the relatively long, ~20 μm, passage between the epithelial cells, neutrophils encounter several junctional complex proteins that oppose passage of the phagocyte.54 Although there are no reports, to date, of interaction between TREM-1 and any of these proteins or with adhesion proteins at either the basolateral or apical surfaces of the epithelia, it is interesting to speculate that TREM-1 expressing neutrophils gain passage through the epithelial monolayer by enabling cleavage of 1 or more junctional proteins. Neutrophil-derived matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and elastase were observed to increase epithelial permeability by cleavage of desmoglein-2 and e-cadherin in intestinal and lung epithelial cells, respectively.55,56 As proinflammatory cytokines secreted either by epithelial or infiltrating phagocytes induces MMP-9 secretion55 and as TREM-1 promotes the secretion of such cytokines, it is possible that TREM-1 expressing leucocytes are better equipped to remodel the tissue architecture as they traverse the parenchyma to reach the site of inflammation. Thus, an examination of how TREM-1 not only modulates neutrophil effector functions but also of how it impacts neutrophil interaction with epithelial cells will yield insights into its actions at the site of infection.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by NIH grant 5R01HL121105-04, NCI award P30CA086862 (to GB), NIH P30ES005605, UL1TR002537, Holder Cancer Center Gift Funds (J.K.T.), NIH/NIAID R01 AI119965 and VA Merit Review grant 1I01BX002108 (L.-A.H.A.)

We are grateful to Prof. Garry Buettner and Brett Wagner of the ESR Facility for their invaluable help with instrument operation and data analysis. EZ-TAXIScan™ assays were completed with generous assistance from Laura C. Whitmore. We are grateful to Shawn Roach for graphical expertise. All imaging was carried out by the Central Microscopy Research Facility a core resource supported by the Vice President for Research & Economic Development, the Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Carver College of Medicine. The data presented herein were obtained at the Flow Cytometry Facility, which is a Carver College of Medicine Core Research Facility/Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center Core Laboratory at the University of Iowa. The Facility is funded through user fees and the financial support of the Carver College of Medicine, Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center, and Iowa City Veteran’s Administration Medical Center.

Abbreviations

- CI

chemotactic index

- CR

complement receptor

- DAMP

damage-associated molecular pattern

- DHR

dihydrorhodamine

- DMPO

5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide

- DPI

diphenyleneiodonium

- DUOX

dual oxidase

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- FCCP

carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptors

- MMP-9

matrix metalloproteinase-9

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- NLR

NOD-like receptors

- NOX

NADPH oxidase

- OCR

oxygen consumption rate

- OpZ

opsonized zymosan

- PKC

protein kinase C

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- TREM-1

triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1

- WT

wild-type

- ZAS

zymosan-activated serum

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nauseef WM, Borregaard N. Neutrophils at work. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:602–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borregaard N Neutrophils, from marrow to microbes. Immunity. 2010;33:657–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mantovani A, Cassatella MA, Costantini C, Jaillon S. Neutrophils in the activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:519–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beutler B Inferences, questions and possibilities in Toll-like receptor signalling. Nature. 2004;430:257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawai T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors and their crosstalk with other innate receptors in infection and immunity. Immunity. 2011;34: 637–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Futosi K, Fodor S, Mocsai A. Neutrophil cell surface receptors and their intracellular signal transduction pathways. Int Immunopharmacol. 2013;17:638–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouchon A, Dietrich J, Colonna M. Cutting edge: inflammatory responses can be triggered by TREM-1, a novel receptor expressed on neutrophils and monocytes. J Immunol. 2000;164:4991–4995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klesney-Tait J, Turnbull IR, Colonna M. The TREM receptor family and signal integration. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1266–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tammaro A, Derive M, Gibot S, Leemans JC, Florquin S, Dessing MC. TREM-1 and its potential ligands in non-infectious diseases: from biology to clinical perspectives. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;177:81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bouchon A, Facchetti F, Weigand MA, Colonna M. TREM-1 amplifies inflammation and is a crucial mediator of septic shock. Nature. 2001;410:1103–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klesney-Tait J, Colonna M. Uncovering the TREM-1-TLR connection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L1374–L1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arts RJ, Joosten LA, van der Meer JW, Netea MG. TREM-1: intracellular signaling pathways and interaction with pattern recognition receptors. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;93:209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibot S, Kolopp-Sarda MN, Bene MC, et al. A soluble form of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 modulates the inflammatory response in murine sepsis. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1419–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibot S, Massin F, Marcou M, et al. TREM-1 promotes survival during septic shock in mice. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:456–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibot S, Cravoisy A, Levy B, Bene MC, Faure G, Bollaert PE. Soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells and the diagnosis of pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:451–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen J The immunopathogenesis of sepsis. Nature. 2002;420: 885–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kouassi KT, Gunasekar P, Agrawal DK, Jadhav GP. TREM-1; is it a pivotal target for cardiovascular diseases. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2018;5 10.3390/jcdd5030045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen AH, Berim IG, Agrawal DK. Chronic inflammation and cancer: emerging roles of triggering receptors expressed on myeloid cells. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2015;11:849–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Genua M, Rutella S, Correale C, Danese S. The triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (TREM) in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis. J Transl Med. 2014;12:293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klesney-Tait J, Keck K, Li X, et al. Transepithelial migration of neutrophils into the lung requires TREM-1. J Clin Invest. 2013;123: 138–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nauseef WM. Biological roles for the NOX family NADPH oxidases. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16961–16965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winterbourn CC, Kettle AJ, Hampton MB. Reactive oxygen species and neutrophil function. Annu Rev Biochem. 2016;85: 765–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hattori H, Subramanian KK, Sakai J, et al. Small-molecule screen identifies reactive oxygen species as key regulators of neutrophil chemotaxis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3546–3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hattori H, Subramanian KK, Sakai J, Luo HR. Reactive oxygen species as signaling molecules in neutrophil chemotaxis. Commun Integr Biol. 2010;3:278–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niethammer P, Grabher C, Look AT, Mitchison TJ. A tissue-scale gradient of hydrogen peroxide mediates rapid wound detection in zebrafish. Nature. 2009;459:996–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woo CH, Yoo MH, You HJ, et al. Transepithelial migration of neutrophils in response to leukotriene B4 is mediated by a reactive oxygen species-extracellular signal-regulated kinase-linked cascade. J Immunol. 2003;170:6273–6279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan B, Han P, Pan L, et al. IL-1beta and reactive oxygen species differentially regulate neutrophil directional migration and Basal random motility in a zebrafish injury-induced inflammation model. J Immunol. 2014;192:5998–6008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung DH, Seaman WE, Daws MR. Characterization of TREM-3, an activating receptor on mouse macrophages: definition of a family of single Ig domain receptors on mouse chromosome 17. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollock JD, Williams DA, Gifford MA, et al. Mouse model of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease, an inherited defect in phagocyte superoxide production. Nat Genet. 1995;9:202–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nauseef WM. Isolation of human neutrophils from venous blood. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;412:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wagner BA, Venkataraman S, Buettner GR. The rate of oxygen utilization by cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:700–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamb FS, Hook JS, Hilkin BM, Huber JN, Volk AP, Moreland JG. Endotoxin priming of neutrophils requires endocytosis and NADPH oxidase-dependent endosomal reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:12395–12404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eslami AC, Pasanphan W, Wagner BA, Buettner GR. Free radicals produced by the oxidation of gallic acid: an electron paramagnetic resonance study. Chem Cent J. 2010;4:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Volk AP, Heise CK, Hougen JL, et al. ClC-3 and IClswell are required for normal neutrophil chemotaxis and shape change. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34315–34326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fortin CF, Lesur O. Effects of TREM-1 activation in human neutrophils: activation of signaling pathways, recruitment into lipid rafts and association with TLR4. Int Immunol. 2007;19:41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Radsak MP, Salih HR, Rammensee HG, Schild H. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 in neutrophil inflammatory responses: differential regulation of activation and survival. J Immunol. 2004;172:4956–4963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalyanaraman B, Darley-Usmar V, Davies KJ, et al. Measuring reactive oxygen and nitrogen species with fluorescent probes: challenges and limitations. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nauseef WM. Detection of superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide production by cellular NADPH oxidases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840:757–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Benna J, Dang PM, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Marie JC, Braut-Boucher F. p47phox, the phagocyte NADPH oxidase/NOX2 organizer: structure, phosphorylation and implication in diseases. Exp Mol Med. 2009;41:217–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ford JW, McVicar DW. TREM and TREM-like receptors in inflammation and disease. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu J, Li J, Salcedo R, Mivechi NF, Trinchieri G, Horuzsko A. The proinflammatory myeloid cell receptor TREM-1 controls Kupffer cell activation and development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3977–3986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boufenzer A, Lemarie J, Simon T, et al. TREM-1 mediates inflammatory injury and cardiac remodeling following myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2015;116:1772–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colonna M TREMs in the immune system and beyond. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nauseef WM. Nox enzymes in immune cells. Semin Immunopathol. 2008;30:195–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Otabor I, Tyagi S, Beurskens FJ, et al. A role for lipid rafts in C1q-triggered O2- generation by human neutrophils. Mol Immunol. 2004;41:185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shao D, Segal AW, Dekker LV. Lipid rafts determine efficiency of NADPH oxidase activation in neutrophils. FEBS Lett. 2003;550: 101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.David A, Fridlich R, Aviram I. The presence of membrane Proteinase 3 in neutrophil lipid rafts and its colocalization with FcgammaRIIIb and cytochrome b558. Exp Cell Res. 2005;308:156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vieth JA, Kim MK, Pan XQ, Schreiber AD, Worth RG. Differential requirement of lipid rafts for FcgammaRIIA mediated effector activities. Cell Immunol. 2010;265:111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou MJ, Lublin DM, Link DC, Brown EJ. Distinct tyrosine kinase activation and Triton X-100 insolubility upon Fc gamma RII or Fc gamma RIIIB ligation in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Implications for immune complex activation of the respiratory burst. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13553–13560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ushio-Fukai M Localizing NADPH oxidase-derived ROS. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:re8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jackson SH, Gallin JI, Holland SM. The p47phox mouse knockout model of chronic granulomatous disease. J Exp Med. 1995;182: 751–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marriott HM, Jackson LE, Wilkinson TS, et al. Reactive oxygen species regulate neutrophil recruitment and survival in pneumococcal pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:887–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morgenstern DE, Gifford MA, Li LL, Doerschuk CM, Dinauer MC. Absence of respiratory burst in X-linked chronic granulomatous disease mice leads to abnormalities in both host defense and inflammatory response to Aspergillus fumigatus. J Exp Med. 1997;185: 207–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zemans RL, Colgan SP, Downey GP. Transepithelial migration of neutrophils: mechanisms and implications for acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:519–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Butin-Israeli V, Houser MC, Feng M, et al. Deposition of microparticles by neutrophils onto inflamed epithelium: a new mechanism to disrupt epithelial intercellular adhesions and promote transepithelial migration. FASEB J. 2016;30:4007–4020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zemans RL, Briones N, Campbell M, et al. Neutrophil transmigration triggers repair of the lung epithelium via beta-catenin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:15990–15995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.