Abstract

This study examined the unique associations of shame-proneness and self-criticism to symptoms of disordered eating and depression among 186 undergraduate students. The study also tested the degree to which self-criticism and shame-proneness accounted for the association between disordered eating and depressive symptoms. Both shame-proneness and self-criticism were significantly related to disordered eating and depressive symptoms. Self-criticism was significantly associated with disordered eating and depressive symptoms, over-and-above shame-proneness, but the reverse was not true. Controlling for shame-proneness, self-criticism also accounted for a significant proportion of the covariance between disordered eating and depressive symptoms, suggesting that self-criticism could account for some of the comorbidity between depression and eating disorders. Findings suggest self-criticism may have incremental utility above-and-beyond shame-proneness as part of a transdiagnostic underlying cognitive substrate for depression and disordered eating. Implications emerge for future research and clinical practice.

Keywords: Depression, disordered eating, shame, self-criticism, transdiagnostic

1. Introduction

Identifying transdiagnostic processes may explain comorbidity among different disorders, clarify basic processes that contribute to psychological impairment, and identify targets for prevention and intervention (Insel, 2014). Research on two highly comorbid forms of psychopathology, depression and disordered eating, could benefit from a transdiagnostic approach involving self-criticism and shame-proneness (Green et al., 2009). Self-criticism and shame-proneness are significantly related to symptoms of depression and disordered eating (e.g., Gee, & Troop, 2003; Dunkley & Grilo, 2007); however, the degree to which they (individually and jointly) account for the high correlation between these disorders remains unclear. The current study examined the unique and combined associations of shame-proneness and self-criticism to symptoms of depression and disordered eating.

Shame-proneness (SP) refers to a tendency to experience shame across a variety of situations (Tangney & Dearing, 2002). Self-criticism (SC) consists of negative self-evaluations triggered by perceived discrepancies between the actual and ideal self (e.g., Beck, 1963; Blatt, 1974). Despite these differences in definitions, the two constructs share considerable conceptual overlap. Namely, SP and SC both involve negative self-evaluation, feelings of inadequacy and incompetence, and self-consciousness (Tangney & Dearing, 2002; Blatt, Eyre, & Wilber, 1984). These characteristics also typify individuals with depression and disordered eating (e.g., Fairburn, Cooper, & Shafran, 2003; Jacobi, Paul, de Zwaan, Nutzinger, & Dahme, 2004; Orth, Berking, & Burkhardt, 2006). Previous research shows that SP and SC are both strongly associated with depression and disordered eating (Cesare et al., 2016; Tangney & Dearing, 2002; Dunkley & Grilo, 2007). Surprisingly, SP and SC have never been simultaneously examined in relation to these psychopathologies, making it difficult to distinguish their unique contributions to the comorbidity between these outcomes.

Although SC and SP share considerable conceptual overlap, their correlation is modest (Shahar et al., 2015), suggesting each may have attributes that are uniquely associated with disordered eating and depressive symptoms. For example, although both SC and SP are self-evaluative constructs, the nature and form of self-evaluation differs between SC and SP.

In shame, negative self-evaluation manifests through negative affect in reaction to specific experiences – typically, a perceived or actual social transgression (Tangney & Dearing, 2002; Wolf, Cohen, Panter, & Insko, 2010). Individuals who are highly shame-prone have a propensity for such reactions. Research shows that elevated affective reactivity (Booij, Snippe, Jeronimus, Wichers, & Wigman, 2018) and cognitive reactivity (reacting with negative affect and negative self-evaluation; Cole et al., 2014) to unpleasant interpersonal experiences predict depressive symptoms. In addition, disordered eating behaviors are often seen as methods of coping with states of negative affect (Smyth et al., 2007) and fluctuations in shame are associated with fluctuations in disordered eating (Goss & Allen, 2009).

SC, conversely, reflects negative self-focused cognitions and accompanying affect that may be internally generated or triggered by external situations (e.g., perceived failure).1 SC thus has both trait-like and state-like characteristics (Zuroff, Sadikaj, Kelly, & Leybman, 2016). Evidence supports SC as a predictor of both depressive symptoms and disordered eating symptoms (Dunkley, Stanislow, Grilo, & McGlashan, 2009; Fennig et al., 2008).

The current study had two hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that SC and SP would each uniquely relate to depressive symptoms and disordered eating. Second, we hypothesized that SC and SP would account for a significant proportion of the covariance between these constructs.

Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants included 186 students recruited from the research subject pool at a mid-sized southern private university. Average age of the participants was 19.21 (SD = 1.89), and 79% of participants were female. The sample was 63% White, 22% Asian or American-Asian, 12% Black, 10% Hispanic, and 3% other.

2.2. Measures

The Test of Self-Conscious Affect – 3 (TOSCA-3; Tangney, Dearing, Wagner, & Gramzow, 2000) was used to measure SP. The TOSCA-3 is a 16-item measure that examines the degree to which respondents would experience shame in response to hypothetical scenarios. The Self-Rating Scale (SRS; Hooley, Ho, Slater, & Lockshin, 2002) was used to measure SC. The SRS is an 8-item measure that examines the degree to which participants generally think self-critically. The global scale of the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q; Fairburn & Beglin, 1994) was used to measure disordered eating. The EDE-Q measures the frequency of maladaptive eating behaviors and attitudes over the past 28 days using both free-response and 7-point Likert scale responses. The Beck Depression Inventory – II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) was used to assess depressive symptoms. The BDI-II measures the severity of 21 depressive symptoms on 4-point scales. We removed the items assessing suicidality (due to safety concerns) and SC (to avoid artificially inflating the correlation between SC and depression due to that item), resulting in 19 remaining items.2 Coefficient alphas for each measure are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pearson Correlations, Means, Standard Deviations

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | α | M | SD | Skew | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depressive Symptoms | .91 | 9.23 | 7.75 | 1.13 | 1.26 | |||

| 2. Disordered Eating Symptoms | .48 | .93 | 1.66 | 1.42 | 0.91 | −0.01 | ||

| 3. Self-criticism | .55 | .44 | .90 | 23.54 | 11.06 | 0.66 | − 0.23 | |

| 4. Shame-proneness | .30 | .28 | .46 | .80 | 48.81 | 11.36 | − 0.08 | − 0.52 |

All correlations significant, ps < .001.

2.3. Procedure

Participants independently completed measures of SC, SP, depressive symptoms, and disordered eating via the Qualtrics online survey system. Graduate research assistants contacted participants who reported elevated depressive or disordered eating symptoms to provide information about online and campus resources.

2.4. Data Analysis

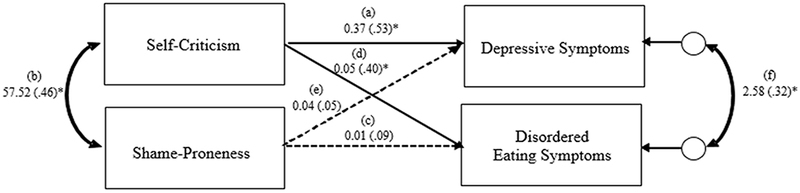

All analyses were conducted via Mplus (version 8.0; Muthén & Muthén, 2017) using maximum likelihood estimation. Hypotheses were tested via path analysis. Figure 1 is a path diagram in which SC and SP predict depressive and disordered eating symptoms. Using Wright’s tracing rules (Loehlin & Beujean, 2016), we calculated the covariance between disordered eating and depressive symptoms explained by SC, by SP, and by both predictors jointly. Because parameters for such statistics do not have a known sampling distribution, we used bias-corrected bootstrapping to generate an empirical sampling distribution, derive 95% confidence intervals, and test significance of estimates.

Figure 1.

Path diagram depicting SC and SP as predictors of depressive symptoms and disordered eating symptoms. Standardized estimates are in parentheses. Paths a and d represent the relation of SC to depressive and disordered eating symptoms, respectively, controlling for SP. Paths e and c represent the relation of SP to depressive and disordered eating symptoms, respectively, controlling for SC. Path b represents the covariance between SC and SP and path f represents the residual covariance between disordered eating symptoms and depressive symptoms. Note: this model is just-identified (i.e., contains 0 degrees of freedom), which precludes a test of fit. *Bolded paths significant, ps <.001.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for SC, SP, disordered eating, and depressive symptoms. All correlations were statistically significant. Skewness and kurtosis values fell within acceptable ranges. Roughly 9.1% of participants (2.6% of males, 10.8% of females) scored at or above the cutoff for clinically significant disordered eating pathology (i.e., global EDE-Q scores ≥ 4.0; Luce, Crowther, & Pole, 2008); 28.9% of participants scored at or above the cutoff for mild depressive symptoms (i.e., BDI-II scores ≥ 14; Dozois, et al., 1998).3

3.2. Testing the unique associations of SC and SP to symptoms of disordered eating and depression.

The following parameter estimates are unstandardized (standardized estimates are shown in Figure 1). Results showed that SC accounted for 28% of the variance in depressive symptoms (path a = .37, SE = .07, p < .001) and 16% of the variance in disordered eating symptoms (path d = .05, SE = .01, p < .001), after controlling for SP. SP accounted for a nonsignificant 0.2% of the variance in depressive symptoms (path e = .04, SE = .05, p = .46) and 0.8% of the variance in disordered eating symptoms (path c = .01, SE = .01, p = .19) after controlling for SC. SC accounted for 82% of the covariance between SP and depressive symptoms (paths b*a = 21.34, p < .001) and 68% of the covariance between SP and disordered eating (paths b*d = 2.99, p < .001).

3.3. Testing the degree to which SP and SC account for the covariance between symptoms of depression and disordered eating.

The total covariance between depressive symptoms and disordered eating symptoms was 5.29 (p < .001) and can be represented as the sum of the following tracings in Figure 1: cov(Dep,DE) = abc+ebd+a(s2sc)d+c(s2sp)e+f.4 The covariance between disordered eating and depressive symptoms explained by SP and SC is equal to abc+ebd+a(s2sc)d+c(s2sp)e. The covariance not explained by SC and SP is equal to f (i.e., the residual covariance between disordered eating and depressive symptoms). SP and SC together explained 2.71 (95% CI [1.58, 4.02]) of the total 5.29 covariance between disordered eating and depressive symptoms. This amounted to 51% of cov(Dep,DE). Most of this was due to SC, which accounted for a significant 43.4% of the total covariance between disordered eating and depressive symptoms, a(s2sc)d = 2.31, 95% CI [1.08, 4.01]. SP explained a nonsignificant amount of the covariance between disordered eating and depressive symptoms, c(s2sp)e = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.04, 0.42]. The remaining covariance between disordered eating and depressive symptoms was f = 2.58, 95% CI [1.41, 3.92], indicating that 49% of the covariance between disordered eating and depressive symptoms was unexplained by SC and SP.

4. Discussion

This was the first study to examine SC and SP simultaneously in relation to disordered eating and depression. Two major findings emerged. First, SP and SC were significantly associated with disordered eating and depressive symptoms when examined separately. When examined together, only SC remained significantly associated with both outcomes (contrary to hypothesis). This finding suggests that self-critical thinking may be pertinent to both disordered eating and depression and that self-critical cognitions associated with shame (e.g., thoughts of worthlessness and inadequacy) might account for the association of SP with disordered eating and depressive symptoms. Such findings are consistent with models of disordered eating and depression that suggest patterns of maladaptive cognition underlie both forms of psychopathology (Beck, 1967, 2008; Fairburn, Cooper, & Shafran, 2003; Lampard, Tasca, Blafour, & Bissada, 2013).

Second, SC accounted for 43.4% of the relation between disordered eating and depressive symptoms, partially supporting our second hypothesis. Although this finding was based on self-report measures of dimensional depression and eating disorder symptoms (not clinical diagnoses), the result raises the possibility that SC constitutes a transdiagnostic factor that accounts for some comorbidity between these two disorders. Self-critical individuals have a propensity for interpreting both individual and interpersonal experiences in a way that generates beliefs of worthlessness and inadequacy (Zuroff & Mongrain, 1987). Such beliefs could directly contribute to depression or indirectly to eating disorders as people often engage in disordered eating behaviors in order to correct perceived inadequacies or attenuate negative affect generated from such beliefs (Fairburn, Cooper, & Shafran, 2003; Stice, Nemeroff, & Shaw, 1996).

Several limitations of this study suggest avenues for future research. First, the design of this study was cross-sectional and therefore precluded examination of the predictive utility of SP and SC. Future research should use prospective designs to clarify whether SC plays a role in either the emergence or maintenance of these disorders.

Second, although many participants in the current study reported moderate to severe symptoms of disordered eating or depression, future research should focus on clinical populations with higher levels of depression and disordered eating. This would also facilitate examination of the different roles that SC plays for different disordered eating subtypes.

Third, the current study relied on single indicators of each construct. Such a measurement strategy can lead to under- and over-estimations of the true relations among the variables when the measures are not perfectly reliable (Cole & Preacher, 2014). To reduce the effects of measurement error, future research could assess all constructs with multiple measures (ideally using diverse measurement methods) and implement latent variable data analytic methods.

Fourth, although SC accounted for 43.4% of the covariance between disordered eating and depressive symptoms, roughly half of the covariance between the two outcomes remained unexplained. Future research should examine other transdiagnostic processes that might account for the remaining covariance.

5. Conclusion

SC was uniquely related with disordered eating and depressive symptoms, controlling for SP; however, SP was unrelated to disordered eating and depressive symptoms when controlling for SC. Additionally, SC accounted for a large proportion of the relation between disordered eating and depressive symptoms. Future research should examine the utility of SC in the etiology, maintenance, and treatment of eating and depressive disorders.

Acknowledgments

The results contained in this paper have not been presented elsewhere in any form. This research was supported in part by the following grant. R. L. Zelkowitz: NIMH training grant T32MH018921-26 and research service award F31MH108241-01A1.

Footnotes

Theorists also suggest that individuals high in SC show a particular susceptibility to criticism of others (e.g., Blatt, 1976; Zuroff, Mongrain, & Santor, 2004)

The suicide ideation item was not administered to participants. The SC item was administered, and results did not differ with it included or excluded from the total BDI-II.

Because the item on the BDI-II assessing suicidal ideation was removed, these proportions were computed using the remaining 20 items.

s2sc and s2sp represent the variances of SC and SP, respectively.

References

- Beck AT (1963). Thinking and depression: I. Idiosyncratic content and cognitive distortions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 9(4), 324–333. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1963.017201600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ (1974). Levels of object representation in anaclitic and introjective depression. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 29(10), 7–157. doi: 10.1080/00797308.1974.11822616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, Rounsaville B, Eyre SL, & Wilber C (1984). The psychodynamics of opiate addiction. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 172(6), 342–352. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198406000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booij SH, Snippe E, Jeronimus BF, Wichers M, & Wigman JTW (2018). Affective reactivity to daily life stress: Relationship to positive psychotic and depressive symptoms in a general population sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 225, 474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesare C, Francesco P, Valentino Z, Barbara D, Olivia R, Gianluca C, Todisco P, & Enrico M (2016). Shame proneness and eating disorders: a comparison between clinical and non-clinical samples. Eating and Weight Disorders, 21(4), 701–707. doi: 10.1007/s40519-016-0328-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin NC, Sterba SK, Sinclair-McBride K, Roeder KM, Zelkowitz R, & Bilsky SA (2014). Peer victimization (and harsh parenting) as developmental correlates of cognitive reactivity, a diathesis for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(2), 336–349. doi: 10.1037/a0036489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, & Preacher KJ (2014). Manifest variable path analysis: Potentially serious and misleading consequences due to uncorrected measurement error. Psychological Methods, 19(2), 300–315. doi: 10.1037/a0033805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DJ, Dobson KS, & Ahnberg JL (1998). A psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Assessment, 10(2), 83–89. doi: 10.1037/10403590.10.2.83 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkley DM, & Grilo CM (2007). Self-criticism, low self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and over-evaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder patients. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(1), 139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkley DM, Stanislow CA, Grilo CM, & McGlashan TH (2009). Self-criticism versus neuroticism in predicting depression and psychosocial impairment over four years in a clinical sample. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 50(4), 335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, & Beglin SJ (1994). Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self‐report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16(4), 363–370. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, & Shafran R (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(5), 509–528. doi: 10.1016/S00057967(02)00088-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fennig S, Hadas A, Itzhaky L, Roe D, Apter A, & Shahar G (2008). Self criticism is a key predictor of eating disorder dimensions among inpatient adolescent females. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41(8), 762–765. doi: 10.1002/eat.20573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee A, & Troop NA (2003). Shame, depressive symptoms and eating, weight and shape concerns in a non-clinical sample. Eating and Weight Disorders, 8(1), 72–75. doi: 10.1007/BF03324992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MA, Scott NA, Cross SE, Liao KY, Hallengren JJ, Davids C, … & Jepson AJ. (2009). Eating disorder behaviors and depression: A minimal relationship beyond social comparison, self-esteem, and body dissatisfaction. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(9), 989–999. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Ho DT, Slater JA, & Lockshin A (2002). Pain insensitivity and self-harming behavior. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Research in Psychopathology. [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR (2014). The NIMH research domain criteria (RDoC) project: precision medicine for psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(4), 395–397. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14020138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi C, Paul T, de Zwaan M, Nutzinger DO, & Dahme B (2004). Specificity of self-concept disturbances in eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 35(2), 204–210. doi: 10.1002/eat.10240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampard AM, Tasca GA, Balfour L, & Bissada H (2013). An evaluation of the transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioural model of eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 21(2), 99–107. doi: 10.1002/erv.2214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loehlin JC, & Beaujean AA (2016). Latent variable models: An introduction to factor, path, and structural equation analysis. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Luce KH, Crowther JH, & Pole M (2008). Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE Q): Norms for undergraduate women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41(3), 273–276. doi: 10.1002/eat.20504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK and Muthén BO (1998-2017). Mplus User’s Guide. Eighth Edition Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén [Google Scholar]

- Orth U, Berking M, & Burkhardt S (2006). Self-conscious emotions and depression: Rumination explains why shame but not guilt is maladaptive. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(12), 1608–1619. doi: 10.1177/0146167206292958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar B, Doron G, & Szepsenwol O (2015). Childhood maltreatment, shame-proneness and self-criticism in social anxiety disorder: A sequential mediational model. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 22(6), 570–579. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, Wonderlich SA, Heron KE, Sliwinski MJ, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, and Engel SG: Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(4), 629–638. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Nemeroff C, & Shaw HE (1996). Test of the dual pathway model of bulimia nervosa: Evidence for dietary restraint and affect regulation mechanisms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 15(3), 340–363. doi: 10.1521/jscp.1996.15.3.340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP & Dearing RL (2002). Shame and Guilt. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Dearing RL, Wagner PE, Gramzow R (2000). The Test of Self-Conscious Affect-3 (TOSCA-3). Fairfax, VA: George Mason University. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf ST, Cohen TR, Panter AT, & Insko CA (2010). Shame proneness and guilt proneness: Toward the further understanding of reactions to public and private transgressions. Self and Identity, 9, 337–362. doi: 10.1080/15298860903106843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zuroff DC, Sadikaj G, Kelly AC, & Leybman MJ (2016). Conceptualizing and measuring self-criticism as both a personality trait and a personality state. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98(1), 14–21. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2015.1044604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuroff DC, & Mongrain M (1987). Dependency and self-criticism: Vulnerability factors for depressive affective states. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 96(1), 14–22. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.96.1.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuroff DC, Mongrain M, & Santor DA (2004). Conceptualizing and measuring personality vulnerability to depression: Comment on Coyne and Whiffen (1995). Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 489–511. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]