Abstract

Introduction:

Hereditary pancreatitis (HP), an autosomal dominant disease typically caused by mutations in PRSS1, has a broad range of clinical characteristics and high cumulative risk of pancreatic cancer. We describe survival and pancreatic cancer risk in the largest HP cohort in the US.

Methods:

HP probands and family members prospectively recruited from 1995 to 2013 completed medical and family history questionnaires, and provided blood for DNA testing. Overall survival (until 12/3½015) was determined from the Social Security Death Index (SSDI), National Death Index (NDI) and family members. Cause of death was obtained from the NDI.

Results:

217 PRSS1 carriers (181 symptomatic) formed the study cohort. The most frequently detected mutations were p.R122H (83.9%) and p.N29I (11.5%). Thirty-seven PRSS1 carriers (30 symptomatic, 7 asymptomatic) were deceased at conclusion of the study (5 from pancreatic cancer). Median overall survival was 79.3 years (IQR 72.2–85.2). Risk of pancreatic cancer was significantly greater than age-and sex-matched SEER data (SIR 59, 95% CI 19–138), and cumulative risk was 7.2% (95% CI 0–15.4) at 70 years.

Discussion:

We confirm prior observations on survival and pancreatic cancer SIR in PRSS1 subjects. Although risk of pancreatic cancer was significantly high in these patients, its cumulative risk was much lower than previous reports.

Keywords: Hereditary pancreatitis, PRSS1, pancreatic cancer

INTRODUCTION

Hereditary pancreatitis (HP) is a highly penetrant, autosomal dominant disorder characterized by acute pancreatitis (AP) in childhood and chronic pancreatitis (CP) in young adults. Between 65–100% of families with HP have a gain-of-function mutation in the cationic trypsinogen gene (PRSS1) (1–3). The two most commonly identified pathogenic PRSS1 mutations are p.R122H and p.N29I (90%) (4, 5), while less common mutations include A16V, R122C, N29T, D22G, and K23R (4). In HP kindreds without a single causal missense variant, the genetic etiology may be more complex, such as from PRSS1 duplication and triplication copy number variants (CNVs) (6, 7) or combinations of disease-associated variants (8).

Clinical features include abdominal pain, diabetes mellitus and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, but the clinical presentation, natural history, complications and need for surgery varies among patients (4, 5, 9, 10). Although the overall survival in HP patients is similar to the background population, the cumulative risk of its most severe complication, pancreatic cancer, has been reported to be as high as 40% at age 70 years (10). The cause of death other than pancreatic cancer in HP patients has only been evaluated in one study (11). Moreover, no prior study has evaluated silent PRSS1 carriers to assess if their overall survival or risk of pancreatic cancer is similar to symptomatic PRSS1 carriers.

Several large studies of HP families from European populations were previously published, including estimates of pancreatic cancer risk (4, 11, 12). Clinical characterization of HP in the United States is limited to initial reports from the Midwest Multicenter Study Group describing the regional distribution of HP cases (13) and the clinical characteristics of 32 HP (28 PRSS1 p.R122H) probands in a large kindred (14).

Here we describe overall survival, cause of death and risk of pancreatic cancer in both symptomatic and asymptomatic PRSS1 carriers in a prospective HP registry in the United States. While we confirm prior clinical findings and a survival similar to the background population, we found the cumulative risk of pancreatic cancer to be much lower than previously reported, and that silent carriers are also at an increased risk of pancreatic cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The HP Study

The HP study was initiated at the University of Pittsburgh in 1995 to investigate the clinical characteristics of HP, to evaluate kindreds with known or suspected HP, and to obtain biological samples for further research. Family members were recruited under IRB protocols as described (13).

Data Collection

Structured case report forms were completed by study subjects to provide information on demographics, family history of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer (minimally, three-generations with construction of pedigrees), alcohol and tobacco exposure, symptoms related to pancreatitis, history of diabetes and exocrine insufficiency, findings on imaging tests, treatment and surgical interventions for pancreatitis, and quality of life. Subjects are also asked to report on their family history of smoking, alcohol, diabetes mellitus and cystic fibrosis. Responses to medical questionnaires and available medical records were reviewed by a licensed physician (CU) for data entry and analyses.

Genetic Testing

Blood was collected, and buffy coats stored at −80°C. DNA was extracted and assessed for the following PRSS1 mutations: R122H, N29I, R122C, K23R, A16V, and R116C with Sanger sequence verification (n=195) (1), clinical test reports (n=20), or obligate status (n=2).

HP Group for this Study

The cohort included subjects with a history of pancreatitis who were enrolled from 1995–2013 and an identified PRSS1 mutation (R122H, N29I, R122C, K23R, or A16V). Subjects were classified into two groups: (1) symptomatic PRSS1 subjects; and (2) silent PRSS1 carriers.

Survival

Although we made attempts to follow-up for clinical outcomes, only a subset of subjects could be contacted to provide this information. Therefore, we used the Social Security Death Index (SSDI) (15) and the National Death Index (NDI) (16) through the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) (16) as the primary sources for an unbiased assessment of vital statistics (17–19) in a combined approach (20, 21). This approach did not rely on the ability to re-contact study participants.

We searched the SSDI with participant identifying information to identify deceased participants until March 2014 (22). To expand death information through 2015, identifying information on subjects was also submitted to the NDI. Recommendations from the NCHS (23) and Fillenbaum et al (24) were used to determine ‘true’ matches between NDI decedents and study subjects. Information was supplemented by reports from family members upon re-contact and obituary searches.

Cause of death codes (ICD-9 and ICD-10) for deceased participants were obtained from NDI documentation, and special attention was paid to diagnosis codes for pancreatic cancer, other cancers, and pancreatitis-related deaths.

Statistical Methods

The general cohort statistics are reported as counts and percentages, or median, range and interquartile range (IQR). Comparisons between groups were made using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous data and the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, when applicable, for categorical data.

Time to event was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier non-parametric method. Cumulative incidence was estimated with 1-S(t) with a log-log 95% confidence interval. Subjects who did not experience the event were censored at the last known age at which they were free of the event. Survival was calculated by censoring living participants at 12/3½015. The log-rank test was used to determine the significance of differences according to sex, mutation type, smoking status, and diabetes mellitus.

SEER age-specific (5-year interval) and sex-adjusted death rates of U.S. whites (2009–2013) for pancreatic cancer (25) were used to calculate the standardized incidence ratio. Estimates for expected number of deaths were calculated using age at December 31, 2015 or death. Statistical analyses were completed in R 3.4.0 (26) with a critical level of significance of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Study Subjects

A total of 181 symptomatic PRSS1 carriers and 36 silent carriers (had a PRSS1 mutation but no reported history evidence of pancreatitis) were identified from the HP Study. The two most common mutations detected among the carriers were R122H (83.9%, 182/217), and N29I (11.5%, 25/217), while the remaining ~4.5% had other mutations – R112C (1.4%, 3/217), A16V (1.8%, 4/217), and R116C (1.4%, 3/217). The distribution of mutations among symptomatic and silent carriers was similar, except that A16V was not identified among silent carriers.

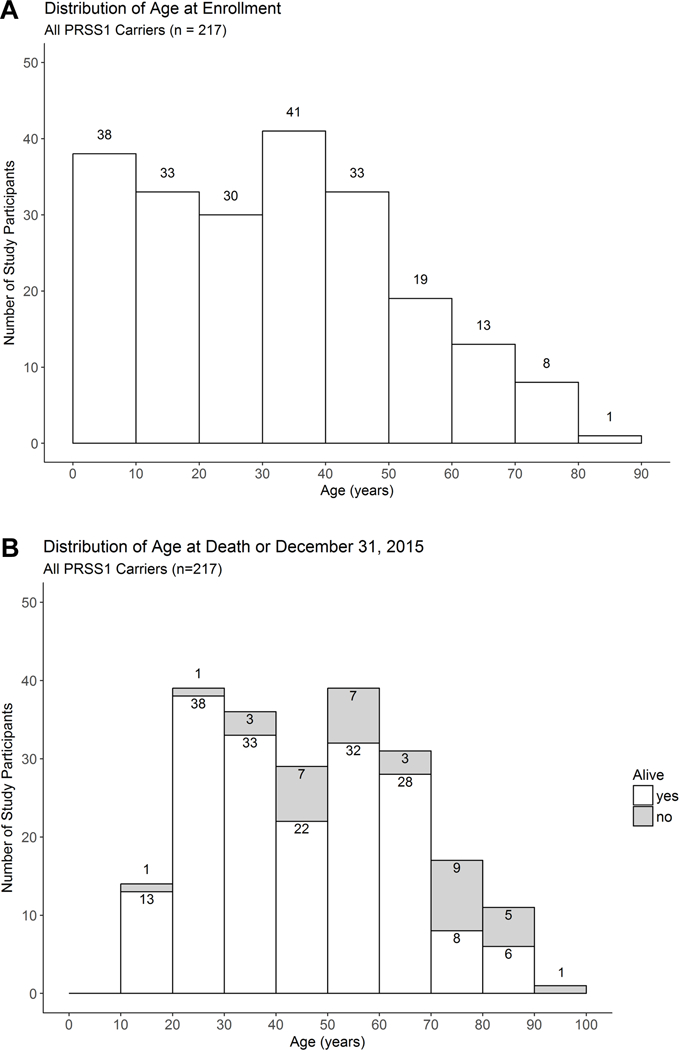

Of 181 symptomatic carriers, 87 (48.1%) were male and all 177 subjects who reported ethnicity/race were Caucasian/white. The median age at enrollment was 30.4 years (IQR 13.7–44.5; range <1–77) and 59/181 (33%) were minors at enrollment (< 18 years) (Figure 1A). Ever smoking or drinking was reported by 27.6% (50/181; in adults – 39.1% [50/128]) and 32% (58/181; in adults – 44.5% [57/128]) of subjects respectively. Heavy drinking (≥5 drinks per day) was reported by only 5 subjects.

Figure 1:

Distribution of (A) age at enrollment and (B) age at death or the end of the study (December 31, 2015).

Median age at enrollment of silent PRSS1 carriers was 40.6 years (IQR 23.6–49.1; range 2.2–93) and 38.8% (14/36) were male. Ever smoking or drinking was reported by 8 (22.2%) and 13 (36.1%) subjects respectively, and one subject reported drinking an average of 5 drinks per day. There was no significant difference between age at enrollment, % male, ever smoking or ever drinking between silent and symptomatic carriers. Only 1 reported a cholecystectomy at age 57.

The median age for diagnosis of any pancreatitis was 7 years (IQR 3–16; range <1–73). The age at which a diagnosis of HP was made (available in 69 subjects) was 13 years (IQR 4.5–25; range 1–66). Of these 69 subjects, the diagnosis of HP coincided (≤ 1 year) with pancreatitis diagnosis in 62.3%; in the remaining subjects, the median delay in diagnosis of HP was 10 years (range 2–64 years). Penetrance (83.4%; 18½17) and clinical features of symptomatic carriers (not reported) were consistent with previous reports (4, 5, 27).

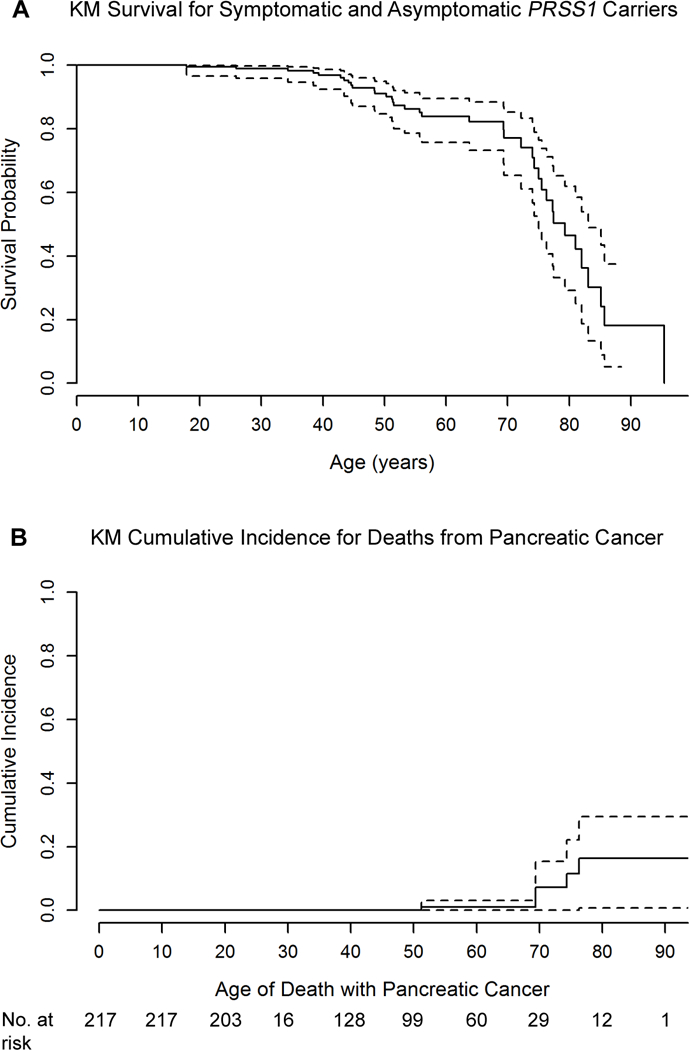

Survival

A total of 37/217 (16.6%; symptomatic -30/181, 15.8%; silent -7/36, 19.4%) PRSS1 carriers were deceased as of December 31, 2015 (Figure 1B). Median time from enrollment until the time of death or December 31, 2015 for all PRSS1 carriers was 16.25 years (range <1 – 20.6 years), and median age at death was 56.1 years (range 17.9–95.5 years). For participants alive at the conclusion of the study, median age was 43.6 years (range 13.5–88.5 years). Median overall survival was 79.3 years (IQR 72.2–85.2) (Figure 2A), which appears similar to the expected survival for whites in the United States -79.1 years in 2012 (28). Sex, type of mutation (R122H, N29I), smoking status, and diabetes mellitus were not associated with significant differences in survival.

Figure 2:

(A) Survival and (B) cumulative incidence of pancreatic cancer for all PRSS1 carriers. Individuals were censored at age on 12/3½015 (A and B) or death unrelated to pancreatic malignancy (B).

Family members of 67.6% (25/37) of decedents were contacted (16/20, 80% with any cancer or pancreatitis-reported cause of death). Among silent carriers, family members for 71.4% (5/7) of deceased subjects were re-contacted, all of which confirmed absence of clinical evidence of pancreatitis until death.

Pancreatic Cancer

Pancreatic cancer was the confirmed cause of death in 5 individuals – 3 symptomatic carriers and 2 asymptomatic carriers (median age of death – 69 years; range 51–76 years) (Table 1). Of note, one death in the NDI was coded as prostate cancer but was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer <1 year before death at the age of 69, confirmed by medical records and pathology. The cumulative risk for death related to pancreatic cancer at 70 years was 7.2% (log-log CI 95% 0–15.4) (Figure 2B). When compared with age and sex-adjusted whites in the US population, the standard incidence rate (SIR) for pancreatic cancer in PRSS1 carriers was significantly greater (SIR 59; 95% CI 19–138). There were no significant differences in SIR or cumulative risk between symptomatic and silent carriers.

Table 1:

Cause and Age of Death in PRSS1 Carriers

| Category | Underlying Cause of Death | Symptomatic (y/n) |

Age at Death |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Pancreatic

Cancer |

Malignant neoplasm of pancreas, unspecified† | yes | 51 |

| 2 | Malignant neoplasm of pancreas, unspecified† | yes | 74 | |

| 3 | Malignant neoplasm of pancreas, unspecified† | yes | 76 | |

| 4 | Malignant neoplasm of pancreas*† | no | 69 | |

| 5 | Malignant neoplasm of pancreas, unspecified† | no | 69 | |

| 6 | Other Cancer | Malignant neoplasm of unspecified part of bronchus or lung†‡ | yes | 51 |

| 7 | Malignant neoplasm of unspecified part of bronchus or lung | yes | 79 | |

| 8 | Malignant neoplasm of ovary† | yes | 55 | |

| 9 | Malignant neoplasm of ovary†‡ | yes | 77 | |

| 10 | Malignant neoplasm of gallbladder† | yes | 74 | |

| 11 | Malignant neoplasm of stomach, unspecified† | no | 72 | |

| 12 | Malignant neoplasm of brain, unspecified | no | 77 | |

| 13 |

Non-malignant

Pancreatic Disease |

Acute pancreatitis, unspecified†

Cardiovascular disease reported by family |

yes | 44 |

| 14 | Acute pancreatitis, unspecified† | yes | 48 | |

| 15 | Other chronic pancreatitis† | yes | 38 | |

| 16 | Other chronic pancreatitis† | yes | 39 | |

| 17 | Other chronic pancreatitis† | yes | 44 | |

| 18 | Other chronic pancreatitis | yes | 48 | |

| 19 | Other chronic pancreatitis† | yes | 51 | |

| 20 | Disease of pancreas, unspecified | yes | 34 | |

| 21 |

Cardiovascular

Disease |

Acute myocardial infarction, unspecified† | yes | 43 |

| 22 | Atherosclerotic heart disease of native coronary artery | yes | 56 | |

| 23 | Heart failure† | yes | 63 | |

| 24 | Hypertensive heart disease with heart failure† | yes | 85 | |

| 25 | Acute myocardial infarction† | no | 82 | |

| 26 | Endocrine | Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus with Neurological Complications† | yes | 25 |

| 27 | Type 1 diabetes mellitus without complications† (and cardiovascular disease) | yes | 75 | |

| 28 | Hypoglycemia, Unspecified | yes | 75 | |

| 29 | Pulmonary | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, unspecified† | yes | 85 |

| 30 | Cerebrovascular | Stroke (reported by family)† | yes | 83 |

| 31 | Acute, but Ill-defined Cerebrovascular Disease | no | 95 | |

| 32 | Renal | Chronic kidney disease, unspecified | yes | 81 |

| 33 | Other/External† | Accidental Injury | yes | 17 |

| 34 | Assault | yes | 42 | |

| 35 | Accidental Poisoning | yes | 44 | |

| 36 | Pneumonia | yes | 50 | |

| 37 | Alcohol Abuse† | no | 53 | |

Misdiagnosed as prostate cancer on death certificate

Family members contacted

Family members unsure if there may have been a pancreas cancer primary

All five subjects who developed pancreatic cancer were PRSS1 R122H carriers and four were male. Absence of clinical manifestations of pancreatitis in both silent carriers were confirmed by first degree relatives (FDRs). All but one reported ever drinking. Two were self-reported smokers – one symptomatic carrier (age of death -74 years) smoked for 30 years (≥1 pack/day) and reported consuming 5 drinks/day; and one silent carrier (age of death – 69 years) smoked ≥1 pack per day for at least 45 years. Three subjects reported a diagnosis of diabetes. Two pancreatic cancer decedents were second-degree relatives – one silent carrier (non-drinker, non-smoker, age of death – 69 years) and one symptomatic carrier (smoker, drinker, age of death – 74 years noted above). In three pancreatic cancer subjects, PRSS1 R122H was inherited paternally (suspected by family history), while in the remaining two it was inherited through maternal transmission (1 of 2 confirmed by testing).

Other Causes of Death

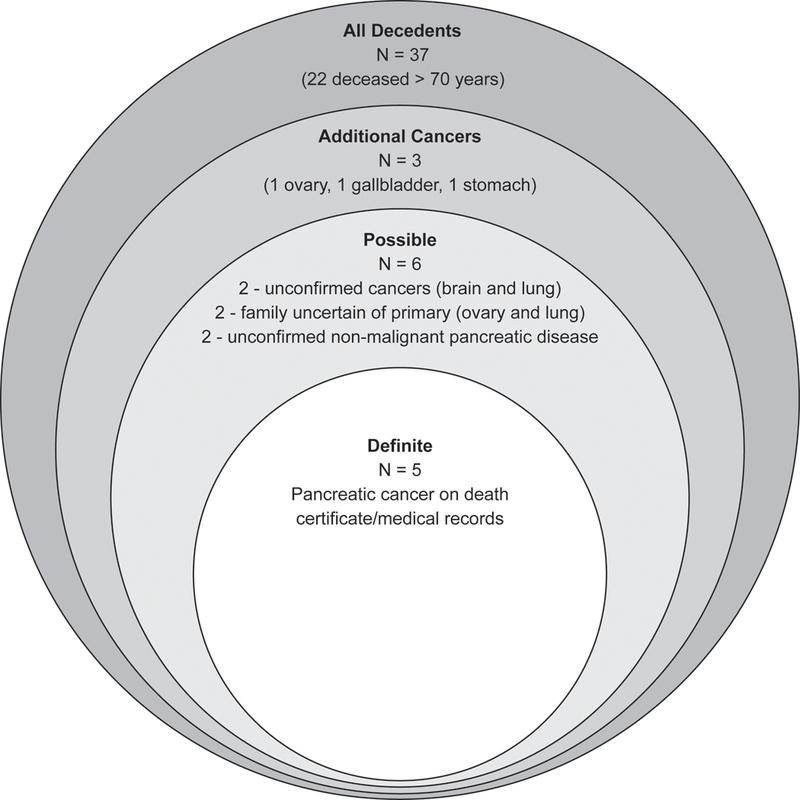

The cause of death in the remaining 32 subjects is shown in Table 1. Cause of death and absence of pancreatic cancer were confirmed in 20/32 subjects by family members who could be re-contacted (62.5%). Non-malignant pancreatic causes of death were reported as the underlying cause of death in 29.6% (8/27) of the remaining deaths in symptomatic carriers, 75% (6/8) of which were confirmed by family members as non-malignant disease (5 by FDRs). Extrapancreatic malignancy was the underlying cause of death in 21.9% of non-pancreatic cancer deaths (7/32), 3 of which were confirmed by family members (2 by FDRs) as non-pancreatic primaries and 2 for which family members were unsure if it may have been a metastasis (Figure 3). Considering the possibility that these 7 extrapancreatic cancer deaths and the 2 unconfirmed deaths from non-malignant pancreatic disease had pancreatic primaries (14 total possible cases), the risk for pancreatic cancer may be as high as 10.9% at 70 years (95% CI 6.5–34.6%) (Supplementary Table 1). Taking the extreme assumption that all decedents had pancreatic cancer, the risk would be as high as 22.9% (95% CI 12.4–32.2%) at 70 years.

Figure 3:

Classification Tiers for Possible Cases of Pancreatic Cancer Five cases of pancreatic cancer we identified from death certificates or medical records. An additional 6 cases were identified as possibly pancreatic cancer according to cause of death – 2 unconfirmed extrapancreatic malignancies (brain and lung), 2 extrapancreatic malignancies for which family members were unsure of a possible pancreas primary (ovary and lung), and 2 unconfirmed non-malignant pancreatic disease. An additional 3 cancer deaths (ovary, gallbladder, stomach) were confirmed as extrapancreatic malignancies by family members. Finally, a total of 37 deceased PRSS1 carriers were identified, 22 of which were deceased before age 70.

*Area of circles is not to scale

DISCUSSION

This study represents the largest prospectively ascertained cohort of HP in the United States. A core PRSS1 mutation was detected in over 90% of families meeting criteria for HP, with a high penetrance. Overall survival in PRSS1 carriers appears to be similar to the general population. Although pancreatic cancer risk in PRSS1 carriers was similar to previous reports (SIR 59; CI 95% 19–138), the estimated cumulative risk for death related to pancreatic cancer at age 70 years was much lower (7.2%, log-log CI 95% 0–15.4).

Internationally, the majority of PRSS1 kindreds have been identified in the USA (13, 29, 30) and Europe (4, 31, 32), though few have also been reported from Japan (33), South America (34, 35), and Thailand (36).To date, HP has not been reported in patients of African ancestry. As in previous reports, the most common PRSS1 mutations identified were R122H (83.9%) and N29I (11.5% of PRSS1 HP cases) (1, 3). Previous reports have demonstrated that gene x gene interactions confer an increased risk for CP, such as through co-inheritance of defects in CFTR bicarbonate conductance and variants in SPINK1 (37, 38). However, preliminary genetic analysis suggested a low power in this study to determine the influence of co-existing variants in SPINK1, CTRC, and CFTR on survival and pancreatic cancer risk in PRSS1 carriers. With respect to cancer risk, a recent study of mouse models of pancreatic chronic inflammation found that all mice lacking pancreatic TP53 developed pancreatic cancer, compared to none of the TP53 wildtype mice (39), suggesting that inflammation alone is not sufficient to cause pancreatic cancer. Furthermore, another HP study found that the grade of dysplasia and number of PanIN lesions in HP pancreata does not correlate with age, smoking, calcifications, fibrosis, or inflammation (40). Together, these findings suggest that additional genetic variants in patients with chronic pancreatitis may modify risk for pancreatic cancer.

In contrast to CP of all etiologies (41, 42), like previous reports, the survival of PRSS1 carriers in our study appears to be similar to the general population (11). Cancer was the most frequent cause of death in PRSS1 carriers (32.4%), of which less than half (42%) were from pancreatic cancer (41, 43). Interestingly, non-malignant pancreatic disease was mentioned on death reports as the second most common cause (21.6%), followed by cardiovascular disease (13.5%), which was different than the only other report on HP causes of death (11).

The SIR for pancreatic cancer in this cohort is similar to data reported by Lowenfels, et al. in 1997 (SIR 53; 95% CI 23–105)(10), but somewhat lower that the SIR report by the French in 2009 (SIR 87, 95% CI 42–113) (44). No significant difference in SIR was noted between symptomatic and silent PRSS1 carriers. This finding supports alternative cancer risk mechanisms or the presence of subclinical disease in silent carriers, contributing to inflammation and oncogenesis. Moreover, identification of related individuals with pancreatic cancer suggests the presence of additional genetic factors that may modify familial risk.

Pancreatic cancer is the most dreaded complication of HP -in fact, the risk of pancreatic cancer in previous reports ranges from 18.8–40% by age 70 years (4, 10, 44). Such a high risk has a significant impact not only on patients and their families, but can also influence decision making by physicians and patients. Interestingly, we found the cumulative risk of pancreatic cancer at age 70 years to be much lower than the initial estimate (10), with a more precise estimate reflected by a tighter CI (7.2%; 95% CI 0–15.4).

Assuming all unconfirmed cancers and pancreatitis-related deaths were attributable to pancreatic cancer (11/37), the risk of pancreatic cancer at age 70 years only increases to 9.7% (95% CI 0.5–18). Furthermore, attributing all other confirmed cancer deaths to pancreatic cancer (14/37) increases its risk to only 10.9% (95% CI 6.4–34.6). Finally, assuming all deaths that occurred in our cohort by age 70 were from pancreatic cancer, the cumulative risk is still less than 25% (22.9%, 95% CI 12.4–32.2), which is similar to the EUROPAC esimate (Table 2) (4). There are several potential explanations for this observation – first, few subjects reached age 70 years in two of three previous studies (10, 11, 31 vs. 29 in our cohort), thereby inflating the fraction of patients with pancreatic cancer, and yielding very large CIs of the risk estimates (Table 2); second, initial estimates may have been due to referral bias or lack of genetic testing to identify milder cases; and lastly, it is also possible that new knowledge about the dangers of smoking in the past 2–3 decades may have resulted in significant lifestyle modifications, reducing the risk of cancer. Importantly, the other study with similar numbers of participants living until 70 years (31 v. 29) also found a lower cumulative incidence of 18.8% at 70 years (95% CI 8.6–29) (4), which is within the probable estimates we suggest by including deaths from other cancers and benign pancreatic diseases in our estimates. This observation is significant and should be reassuring to both patients and treating physicians. It also suggests that the actual risk estimates for pancreatic cancer in PRSS1 subjects may be closer to risk estimates in patients with CP from other causes (5% risk over 20 years for any form of CP) (45) than previously recognized. One study suggests that CP patients with SPINK1 or CFTR mutations have a higher risk for pancreatic cancer than patients with alcoholic pancreatitis (46). A higher risk of pancreatic cancer in patients with genetic pancreatitis when compared with alcohol and other forms of pancreatitis is believed to be due to longer duration of inflammatory milieu in these patients. The reason for differences in our observations from those of Midha et al. is unclear. These findings underscore the need for additional studies with a longer duration of follow-up to define the risk of pancreatic cancer in patients with genetic pancreatitis.

Table 2:

Incidence of Pancreatic Cancer in Previous Studies

| Study Population |

SIR (95% CI) |

CI at age 70 (95% CI) |

% with a PRSS1 Mutation |

No. of Pancreatic Cancer Cases |

No. at risk at age 70 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

This Report* USA |

59 (19–138) |

7.2% (0–15.4%) |

100% | 5 | 29 |

| Lowenfels, et al. (1997) International |

53 (23–105) |

40% (9–71%) |

Unknown | 8 | 10 |

| Howes, et al. (2004) EUROPAC |

67 (50–82) |

18.8% (8.6–29%) |

78% | 26 | 31† |

| Rebours, et al. (2009) France |

87 (42–113) |

(at age 75: 53.5% [7–76%]) |

68% | 10 | 11 |

includes symptomatic (n=181) and silent carriers (n=36)

R122H, N29I and negative PRSS1 mutation status only

Our study has limitations. Although we used patient self-reported data as the primary source to evaluate many of the phenotypic characteristics, this information was supplemented by obtaining medical records for verification as and when feasible. To remove any bias from loss to follow-up, we used SSDI and NDI for an unbiased evaluation of pancreatic cancer and overall survival in all study participants. The potential for false and unidentified matches to National Death Index data could have been increased by the absence of social security numbers for some participants. Furthermore, It is possible that the presence of inaccurate and misclassified cause of death information on death certificates (47) could have resulted in a reduced ability to identify all deceased subjects with a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, as suggested by the participant with pancreatic cancer whose cause of death was miscoded as prostate cancer. However, in contrast to other cancers, previous studies have shown an 87–90% agreement between pancreatic cancer diagnosis and death certificate cause of death (48, 49). Therefore, it is unlikely that inaccurate and misclassified cause of death information on death certificates (47) resulted in a reduced ability to identify all deceased subjects with a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Furthermore, obituary searches and family members were used to reduce both false positives and negatives in such cases. We were able to contact family members to confirm the cause of death in 80% (16/20) of patients reported to have died from any cancer or pancreatitis (Supplementary Figure 3).

In conclusion, this study confirms overall survival and an increased risk of pancreatic cancer for hereditary pancreatitis in the United States. This is the first study to evaluate survival, cause of death, and risk of pancreatic cancer in silent PRSS1 carriers. While a high cumulative risk for pancreatic cancer in both symptomatic and silent PRSS1 carriers was identified, this risk was much lower than previous reports, which has direct implications for risk assessment and surgical decision-making.

Supplementary Material

STUDY HIGHLIGHTS.

-

1)WHAT IS CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

-

•HP has significant variability in age of onset of pancreatitis, severity, and risk for complications.

-

•Life expectancy in HP patients is similar to the general population.

-

•HP patients have a high risk for pancreatic cancer–up to 40% by age 70.

-

•

-

2)WHAT IS NEW HERE

-

•We confirm survival and overall pancreatic cancer risk (SIR) for individuals with HP.

-

•Survival, cause of death and pancreatic cancer risk is defined in both symptomatic and silent PRSS1 carriers.

-

•The cumulative risk of pancreatic cancer in PRSS1 carriers was lower than previous estimates-7.2% (95% CI 0–15.4%) at age 70.

-

•

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

The authors would like to thank Sheila Solomon, MS, CGC, and Erin Fink, MS, CGC for enrollment of study subjects and administrative support. Michael O’Connell, PhD assisted with data organization and management. Jessica LaRusch, PhD also assisted with data organization and some genotyping. The authors would also like to thank Albert Lowenfels, MD FACS (New York Medical College, NY) for detailed review of the manuscript and Judah Abberbock, MS (University of Pittsburgh, PA) for statistical consultation.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: Research reported in this publication was supported by National Cancer Institute and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers DK063922 (CAS), U01DK108306 (DY, DCW), DK054709 (DCW) and DK077906 (DY). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

POTENTIAL COMPETING INTERESTS: DCW serves as a consultant for AbbVie, Regeneron and Ariel Precision Medicine and has equity in Ariel Precision Medicine. C Shelton, K Stello, C Umpathy and D Yadav have no conflicts to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Whitcomb DC, Gorry MC, Preston RA, et al. Hereditary pancreatitis is caused by a mutation in the cationic trypsinogen gene. Nat Genet 1996;14:141–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitcomb DC, Preston RA, Aston CE, et al. A gene for hereditary pancreatitis maps to chromosome 7q35. Gastroenterology 1996;110:1975–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorry MC, Gabbaizedeh D, Furey W, et al. Mutations in the cationic trypsinogen gene are associated with recurrent acute and chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 1997;113:1063–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howes N, Lerch MM, Greenhalf W, et al. Clinical and genetic characteristics of hereditary pancreatitis in Europe. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:252–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rebours V, Boutron-Ruault MC, Schnee M, et al. The natural history of hereditary pancreatitis: a national series. Gut 2009;58:97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masson E, Chen JM, Cooper DN, et al. PRSS1 copy number variants and promoter polymorphisms in pancreatitis: common pathogenetic mechanism, different genetic effects. Gut 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le Marechal C, Masson E, Chen JM, et al. Hereditary pancreatitis caused by triplication of the trypsinogen locus. Nat Genet 2006;38:1372–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitcomb DC, LaRusch J, Krasinskas AM, et al. Common genetic variants in the CLDN2 and PRSS1-PRSS2 loci alter risk for alcohol-related and sporadic pancreatitis. Nat Genet 2012;44:1349–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joergensen MT, Brusgaard K, Cruger DG, et al. Genetic, epidemiological, and clinical aspects of hereditary pancreatitis: a population-based cohort study in Denmark. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:1876–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, DiMagno EP, et al. Hereditary pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. International Hereditary Pancreatitis Study Group. J Natl Cancer Inst 1997;89:442–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rebours V, Boutron-Ruault MC, Jooste V, et al. Mortality rate and risk factors in patients with hereditary pancreatitis: uni-and multidimensional analyses. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:2312–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss FU, Zenker M, Ekici AB, et al. Local clustering of PRSS1 R122H mutations in hereditary pancreatitis patients from Northern Germany. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:2585–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Applebaum-Shapiro SE, Finch R, Pfutzer RH, et al. Hereditary pancreatitis in North America: the Pittsburgh-Midwest Multi-Center Pancreatic Study Group Study. Pancreatology 2001;1:439–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sossenheimer MJ, Aston CE, Preston RA, et al. Clinical characteristics of hereditary pancreatitis in a large family, based on high-risk haplotype. The Midwest Multicenter Pancreatic Study Group (MMPSG). Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92:1113–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Social Security Administration. Social Security Death Index, Master File. Social Security Administration. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) National Center for Health Statistics. National Death Index. [cited 20 October 2016]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ndi.htm.

- 17.Wentworth DN, Neaton JD, Rasmussen WL. An evaluation of the Social Security Administration master beneficiary record file and the National Death Index in the ascertainment of vital status. Am J Public Health 1983;73:1270–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huntington JT, Butterfield M, Fisher J, et al. The Social Security Death Index (SSDI) most accurately reflects true survival for older oncology patients. Am J Cancer Res 2013;3:518–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curb JD, Ford CE, Pressel S, et al. Ascertainment of vital status through the National Death Index and the Social Security Administration. Am J Epidemiol 1985;121:754–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchanich JM, Dolan DG, Marsh GM, et al. Underascertainment of deaths using social security records: a recommended solution to a little-known problem. Am J Epidemiol 2005;162:193–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanna DB, Pfeiffer MR, Sackoff JE, et al. Comparing the National Death Index and the Social Security Administration’s Death Master File to ascertain death in HIV surveillance. Public Health Rep 2009;124:850–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935–2014 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Center for Health Statistics. National Death Index user’s guide. Hyattsville, MD. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fillenbaum GG, Burchett BM, Blazer DG. Identifying a national death index match. Am J Epidemiol 2009;170:515–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2013, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD, http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/, based on November 2015 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Renstrom F, Payne F, Nordstrom A, et al. Replication and extension of genome-wide association study results for obesity in 4923 adults from northern Sweden. Hum Mol Genet 2009;18:1489–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joergensen MT, Brusgaard K, Cruger DG, et al. Genetic, epidemiological, and clinical aspects of hereditary pancreatitis: a population-based cohort study in Denmark. The American journal of gastroenterology 2010;105:1876–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song J, da Costa KA, Fischer LM, et al. Polymorphism of the PEMT gene and susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). FASEB J 2005;19:1266–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Comfort MW, Steinberg AG. Pedigree of a family with hereditary chronic relapsing pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 1952;21:54–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kattwinkel J, Lapey A, Di Sant’Agnese PA, et al. Hereditary pancreatitis: three new kindreds and a critical review of the literature. Pediatrics 1973;51:55–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le Bodic L, Schnee M, Georgelin T, et al. An exceptional genealogy for hereditary chronic pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci 1996;41:1504–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sibert JR. Hereditary pancreatitis in England and Wales. J Med Genet 1978;15:189–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Otsuki M, Nishimori I, Hayakawa T, et al. Hereditary pancreatitis: clinical characteristics and diagnostic criteria in Japan. Pancreas 2004;28:200–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dytz MG, Mendes de Melo J, de Castro Santos O, et al. Hereditary Pancreatitis Associated With the N29T Mutation of the PRSS1 Gene in a Brazilian Family: A Case-Control Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solomon S, Gelrud A, Whitcomb DC. Low penetrance pancreatitis phenotype in a Venezuelan kindred with a PRSS1 R122H mutation. JOP 2013;14:187–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pho-Iam T, Thongnoppakhun W, Yenchitsomanus PT, et al. A Thai family with hereditary pancreatitis and increased cancer risk due to a mutation in PRSS1 gene. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:1634–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosendahl J, Landt O, Bernadova J, et al. CFTR, SPINK1, CTRC and PRSS1 variants in chronic pancreatitis: is the role of mutated CFTR overestimated? Gut 2013;62:582–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneider A, Larusch J, Sun X, et al. Combined bicarbonate conductance-impairing variants in CFTR and SPINK1 variants are associated with chronic pancreatitis in patients without cystic fibrosis. Gastroenterology 2011;140:162–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swidnicka-Siergiejko AK, Gomez-Chou SB, Cruz-Monserrate Z, et al. Chronic inflammation initiates multiple forms of K-Ras-independent mouse pancreatic cancer in the absence of TP53. Oncogene 2017;36:3149–3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rebours V, Levy P, Mosnier JF, et al. Pathology analysis reveals that dysplastic pancreatic ductal lesions are frequent in patients with hereditary pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:206–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yadav D, Timmons L, Benson JT, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and survival of chronic pancreatitis: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:2192–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nojgaard C, Bendtsen F, Becker U, et al. Danish patients with chronic pancreatitis have a four-fold higher mortality rate than the Danish population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:384–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bang UC, Benfield T, Hyldstrup L, et al. Mortality, cancer, and comorbidities associated with chronic pancreatitis: a Danish nationwide matched-cohort study. Gastroenterology 2014;146:989–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rebours V, Boutron-Ruault MC, Schnee M, et al. Risk of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in patients with hereditary pancreatitis: a national exhaustive series. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:111–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raimondi S, Lowenfels AB, Morselli-Labate AM, et al. Pancreatic cancer in chronic pancreatitis; aetiology, incidence, and early detection. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2010;24:349–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Midha S, Sreenivas V, Kabra M, et al. Genetically Determined Chronic Pancreatitis but not Alcoholic Pancreatitis Is a Strong Risk Factor for Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreas 2016;45:1478–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mieno MN, Tanaka N, Arai T, et al. Accuracy of Death Certificates and Assessment of Factors for Misclassification of Underlying Cause of Death. J Epidemiol 2016;26:191–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Percy C, Stanek E 3rd,, Gloeckler L. Accuracy of cancer death certificates and its effect on cancer mortality statistics. Am J Public Health 1981;71:242–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lund JL, Harlan LC, Yabroff KR, et al. Should cause of death from the death certificate be used to examine cancer-specific survival? A study of patients with distant stage disease. Cancer Invest 2010;28:758–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.