Abstract

Anorexia nervosa (AN) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) are highly comorbid. However, little research has examined which specific cognitive-behavioral aspects (e.g., checking, obsessing) of OCD are most relevant in those with AN. Furthermore, there is no research examining aspects of OCD in Atypical AN. The current two studies (N=139 and N=115 individuals diagnosed with AN/Atypical AN) examined a) which aspects of OCD were most related to AN symptomatology and b) if there were differences in OCD between individuals diagnosed with AN vs Atypical AN. We found that obsessing was most related to AN symptoms. We also found that there were no substantial significant differences between AN and Atypical AN. These findings add to the literature suggesting minimal differences between AN and Atypical AN, specifically regarding OCD symptomatology. These findings clarify that obsessions (rather than compulsions) may be the specific aspect of OCD most warranting treatment intervention in AN and Atypical AN.

Keywords: anorexia nervosa, obsessive-compulsive disorder, obsessions, atypical anorexia nervosa

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a serious mental illness, carrying a high risk of mortality and causing extreme suffering and impairment (Klump, Bulik, Kaye, Treasure, & Tyson, 2009). Part of this impairment is due to the high rates of comorbidity, with rates estimated up to 85% (Pallister & Waller, 2008). One frequently co-occurring disorder is Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). Estimates suggest that between 35-44% of individuals with AN also meet criteria for OCD (Halmi et. al., 2005; LaSalle et al., 2004; Pinto, Mancebo, Eisen, Pagano, & Rasmussen, 2006; Rubenstein et. al., 1993; Swinbourne & Touyz, 2007).

In addition to the frequent co-occurrence, AN-OCD has a strong, positive genetic correlation, (~55%; Anttila et al., 2018; Cederlof et al., 2015; Mas et al., 2013), suggesting a shared etiology between AN and OCD. Further, other work has shown that eating disorder (ED) cognitions and behaviors serve a function similar to obsessions and compulsions (e.g., as a temporary relief for anxiety, while predicting longer term increases in anxiety and ED symptoms or temporary safety behaviors) (Levinson et al., 2018). Overall, there is strong evidence for both genotypic and phenotypic similarity between OCD and EDs. However, there is a lack of research exploring the relationship between specific ED symptoms (e.g., drive for thinness, bulimia symptoms) and specific dimensions of OCD (e.g., obsessions, checking behaviors).

OCD is a heterogeneous disorder consisting of many different cognitive-behavioral aspects, including; washing, checking, ordering, hoarding, obsessing, and neutralizing (Foa, Kozak, Salkovskis, Coles, & Amir, 1998; Foa et al., 2002). Obsessing is a cognitive aspect, whereas, washing, checking, ordering, hoarding, and neutralizing focus primarily on OCD behaviors in response to obsessions. Washing is focused on fears of contamination (e.g., repeatedly washing one’s hands). Checking focuses on compulsions to check certain objects or places in order to ascertain that they are a certain way, (e.g., checking to ensure one has not run over an animal). Ordering focuses on a preference for an individual to have or do things a certain way or in a specific order (e.g., arranging books in a certain manner). Obsessing focuses on the tendency to have intrusive thoughts or repeated thoughts about a specific subject (e.g., intrusive violent thoughts). Hoarding focuses on the tendency to collect certain things that do not have value (e.g., collecting old envelopes). Finally, Neutralizing focuses on compulsions to do certain behaviors in order to “cancel out” certain other behaviors conceptualized as negative or bad.

Each of these dimensions of OCD are uniquely correlated with different types of psychopathology (Campos et al., 2015; Torres, Cruz, Vicentini, Lima, & Ramos-Cerqueira, 2016). For example, obsessing, hoarding, and washing are associated with suicidal behaviors (Campos et al., 2015); the severity of alcohol dependence has been significantly associated with neutralizing and ordering (Campos et al., 2015); and obsessing is associated with psychosis severity (Fernandez-Egea, Worbe, Bernardo, & Robbins, 2018). However, the way in which these specific dimensions of OCD relate to EDs is not well established.

To date, there have been two studies that examined these specific dimensions of OCD in ED samples (Davies, Liao, Campbell, & Tchanturia, 2009; Naylor, Mountford, & Brown, 2011). Naylor et al. (2011) found that women with AN and bulimia nervosa (BN) report significantly higher scores on each of the six dimensions of OCD than do healthy controls. They also found that overall OCD dimensions were associated with exercise and overall ED pathology, but did not examine the associations between each dimension of OCD separately (rather they used the total OCD score). A second study, Davies et al. (2009), also found that scores on each dimension of OCD, with the exception of hoarding, were significantly elevated in individuals with a diagnosis of AN and BN versus healthy controls. They also found a significant correlation between overall ED pathology and three dimensions of OCD: neutralizing, obsessing, and ordering.

Though these studies represent an important first step in understanding the relationship between dimensions of OCD and ED pathology, more research is needed to test the unique relationships between dimensions of OCD and specific ED symptoms, to understand the most important components of OCD cognitions and behaviors in the treatment of EDs. Further, there has been no research testing OCD symptoms in a sample diagnosed with Atypical AN. Atypical AN is a subtype of Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disorders (OSFED), in which all symptoms for AN are met with the exception that body mass index (BMI) is over 18.5 (in AN, an individual must have a BMI under 18.5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Forney, Brown, Holland-Carter, Kennedy, & Keel, 2017). Atypical AN is highly prevalent (2.8% lifetime prevalence compared to 0.8% AN; Stice, Marti, & Rohde, 2013; Whitelaw, Gilbertson, Lee, & Sawyer, 2014), and research reports that Atypical AN is associated with equal or higher impairment and mortality rates than other EDs (Sawyer, Whitelaw, Le Grange, Yeo, & Hughes, 2016). However, little research shows other clear distinctions between AN and Atypical AN, including in terms of psychiatry comorbidity (Moskowitz & Weiselberg, 2017). The literature that does exist suggests that AN and Atypical AN share more similarities than differences, including medical complications, rates of psychiatric comorbidity, psychological symptoms, and restriction behaviors (Coniglio et al., 2017; Moskowitz & Weiselberg, 2017; Sawyer, Whitelaw, Le Grange, Yeo, & Hughes, 2016; Whitelaw, Lee, Gilbertson, & Sawyer, 2018). Indeed, it has been suggested that the only significant differentiating point may be the initial weight (e.g., normal versus overweight) when weight loss began that may have resulted in an AN (underweight) versus Atypical AN (other weight) diagnosis (Forney, Brown, Holland-Carter, Kennedy, & Keel, 2017; Whitelaw et al., 2018). Despite its deadliness and high prevalence, no research has characterized OCD symptomatology in Atypical AN, despite the fact that such comorbidity might lead to increased severity within Atypical AN. However, given the high rates of OCD present in AN, we also expected that OCD dimensions would be highly relevant in Atypical AN. Thus, given the current state of the literature, we would hypothesize no differences between AN and atypical AN in terms of OCD symptom dimensions, given there is no literature to support that such a difference would exist.

In the current study, we surveyed a sample of individuals diagnosed with AN or Atypical AN (Study 1: N = 139; 39 AN/100 Atypical AN and Study 2: N = 115; 36 AN/79 Atypical AN), to assess both ED and OCD symptoms. We had two primary goals. First, to test if cognitive-behavioral dimensions of OCD differed between AN and Atypical AN. Second, to detect which unique dimensions of OCD (e.g., obsessing, checking) were related to specific ED symptoms (e.g., drive for thinness, bulimia symptoms, body dissatisfaction, and overall eating pathology). We also tested the relationship between OCD and ED behaviors across time in prospective data (Study 1). We hypothesized that there would be no significant differences in OCD symptoms between AN and Atypical AN. Second, given the strong research showing cognitive distress in EDs, as well as prior research showing a correlation between obsessing and ED symptoms, we hypothesized that obsessing would be the cognitive dimension of OCD most related to ED symptoms. We also hypothesized that obsessions would predict ED behaviors (binge eating, purging, fasting) across time, given high reports of disturbing thoughts in the ED population and their specific documented relationship with ED behaviors.

Methods: Study 1

Participants

Participants were 139 individuals with a current ED diagnosis of either AN (n = 39) or Atypical AN (n = 100). Participants had all recently been discharged from a residential or partial hospitalization ED treatment center (Median days since discharge at start of study = 140 days; Range = one day to 868 days; SD = 40.12), though still actively had an ED diagnosis. One hundred seven participants (82.2%) reported that they were currently in some form of treatment for their ED. Specifically, 88 participants (57.1%) were in outpatient treatment, 11 participants (9.5%) were in intensive outpatient, three participants were in partial hospitalization (3.0%), and five participants (4.7%) were in inpatient or residential treatment. Participants’ median time in treatment was 2.00 hours (SD = 42.26) a week.

The majority of participants were female (n = 135; 97.1%) and European American (n = 130; 94.9%). Other ethnicities reported include multiracial or biracial (n = 3; 2.2%), Hispanic (n = 3; 2.2%), and Black (n = 1; 0.7%). Two participants did not report their ethnicity. Participants ranged in age from 14 to 59 years old, with an average age of 25.61 (SD = 8.44).

Measures

Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale (EDDS; Stice, Telch, & Rizvi, 2000).

The EDDS is a brief self-report measure used to diagnose EDs, such as AN, BN, and binge eating disorder. The EDDS has demonstrated adequate internal consistency, as well as criterion and convergent validity (Stice, Fisher, & Martinez, 2004). Internal consistency in this sample was adequate (α = .78).

Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2; Garner, Olmstead, & Polivy, 1983).

The EDI-2 is a 91-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure psychological features commonly associated with AN and BN. It has been shown to have good internal consistency and good convergent and discriminant validity (Garner et al., 1983), and is frequently used by clinicians for the assessment of ED symptoms (Brookings & Wilson, 1994). Three of the 11 subscales were used for this study: drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, and bulimic symptoms (BN) subscales. We used these three subscales because they are the most commonly used EDI-2 subscales to assess core ED pathology. In the current sample, the body dissatisfaction subscale (α = .92) and bulimic symptoms subscale (α = .91) exhibited excellent internal consistency, and the drive for thinness subscale (α = .76) exhibited adequate internal consistency.

Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire-IV. (EDE-Q IV; Fairburn & Beglin, 1994).

The EDE-Q-IV is a 41-item self-report measure of ED symptoms. Questions correspond to symptoms of EDs (e.g., “Have you attempted to avoid eating any foods which you like in order to influence your shape or weight?”). The EDE-Q-IV uses open response and a 7-point Likert scale to assess the frequency of disordered eating behaviors over the past 28 days. The EDE-Q has demonstrated good internal consistency (Peterson et al., 2007), as well as good reliability and validity (Fairburn & Cooper, 1993; Luce & Crowther, 1999; Mond, Hay, Rodgers, Owen, & Beumont, 2004). The internal consistencies of the four subscales of the EDE-Q-IV: Restraint (α = .88), Eating Concerns (α = .80), Weight Concerns (α = .89), and Shape Concerns (α = .93) were adequate to good.

Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory (OCI; Foa, Kozak, Salkovskis, Coles, & Amir, 1998; Foa et al., 2002).

The OCI-R is an 18-item short version of the original OCI. Similar to the original OCI, the OCI-R is made up of six subscales: Washing (e.g., I wash my hands more often and longer than necessary), Obsessing (e.g., I find it difficult to control my own thoughts), Hoarding (e.g., I collect things I do not need), Ordering (e.g., I get upset if objects are not arranged properly), Checking (e.g., I repeatedly check doors, windows, drawers, etc.), and Neutralizing (e.g., I feel I have to repeat certain numbers). The OCI asks participants to ‘select the number that best describes HOW MUCH that experience has distressed or bothered you during the PAST MONTH.’ Response options range from 0 ‘not at all’ to 4 ‘extremely’. The OCI-R has good factorial, convergent, and discriminant validity, and good test-retest and interrater reliability (Foa et al., 2002). In the current study, the internal consistencies of the washing (α = .82), obsessing (α = .83), ordering (α = .90), checking (α = .75), and neutralizing (α = .84) subscales, as well as the OCI total (α = .92), were acceptable-to-good. The internal consistency of the hoarding (α = .64) subscale was poor. The OCI assesses OCD dimensions not conflated with ED behaviors (as can be seen from example items above).

Procedure

This study was approved by the Washington University Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited from a research database of alumni from a Midwestern ED clinic, where they had recently completed a residential or partial-hospital program. Participants completed online measures of ED symptoms and OCD symptoms at two time points, each one month apart (i.e., Time 1 and Time 2).

Data Analytic Procedure

We first tested if there were differences on any OCD dimension between AN vs Atypical AN. Next, we calculated zero-order correlations between OCD dimensions and ED outcomes. We also calculated cross-sectional multiple regression analyses including all OCD dimensions associated with the three ED symptom indices (drive for thinness, bulimia symptoms, body dissatisfaction), the EDE-Q global index, and the four ED behaviors (binge eating, fasting, purging, and laxative use) as outcomes to test for unique relationships between OCD dimensions and ED outcomes. Last, we tested if there were prospective relationships between Obsessing and ED outcomes using Mplus Version 8 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998-2018) with the MLR estimator. We specifically chose these ED behaviors a-priori because we wanted to test if Obsessing related to specific ED behaviors (rather than symptom indices) across time.

Results

Diagnoses and Clinical Characteristics

The following diagnoses were made based on the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale (Stice et al., 2000): AN (n = 39) or Atypical AN (all symptoms of AN with the exception of the below 18.5 BMI; n = 100) using provided syntax. Mean body mass index (BMI) was 21.00 (Range = 14.92-44.91; SD = 4.44). Twenty participants self-reported having comorbid OCD (14.4%). Other self-reported diagnoses were anxiety disorders (n = 84; 60.4%), depressive disorders (n = 84; 60.4%), post-traumatic stress disorder (n = 20; 14.4%) attention deficient disorder or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (n = 10; 7.1%), borderline personality disorder (n = 6; 4.4%), and bipolar disorder (n = 10; 7.1%).

AN vs. Atypical AN

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for AN vs. Atypical AN in terms of demographics and clinical features. There were no significant differences between AN and Atypical AN on psychotropic medication use, sex, age, or current ED treatment (ps > .208). As hypothesized, there were no significant differences between AN and Atypical AN on any of the OCD subscales.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for all Time 1 variables by diagnosis for both study samples. Equal variances not assumed.

| OCI Overall | Checking | Hoarding | Neutralizing | Obsessing | Ordering | Washing | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dx | AN | Atypical AN |

AN | Atypical AN |

AN | Atypical AN |

AN | Atypical AN |

AN | Atypical AN |

AN | Atypical AN |

AN | Atypical AN |

|

| Study 1 (N=139) |

Mean | 18.57 | 17.49 | 2.24 | 2.32 | 1.91 | 2.10 | 2.21 | 2.64 | 4.53 | 4.26 | 4.94 | 4.24 | 2.49 | 2.00 |

| SD | 14.28 | 13.23 | 2.45 | 2.56 | 2.07 | 2.41 | 2.95 | 3.32 | 3.76 | 3.12 | 3.30 | 3.57 | 2.74 | 2.66 | |

| t-tests | 0.36 | −0.17 | −0.43 | −0.71 | 0.36 | 1.02 | 0.88 | ||||||||

| p-values | .718 | .862 | .669 | .479 | .719 | .313 | .384 | ||||||||

| Cohen’s d | .078 | .031 | .084 | .136 | .078 | .203 | .181 | ||||||||

| Study 2 (N=115) |

Mean | 24.40 | 21.50 | 1.20 | 1.10 | 1.07 | 1.02 | 1.08 | 0.94 | 1.83 | 1.78 | 2.11 | 1.51 | 0.86 | 0.87 |

| SD | 12.66 | 14.33 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 0.84 | 1.21 | 1.14 | 1.09 | 1.21 | 1.08 | 1.27 | 0.90 | 1.08 | |

| t-tests | 1.07 | 0.53 | 0.25 | 0.58 | 0.24 | 2.55 | 0.01 | ||||||||

| p-values | .288 | .599 | .805 | .561 | .813 | .013 | .970 | ||||||||

| Cohen’s d | .214 | .098 | .054 | .119 | .043 | .508 | .010 | ||||||||

Note. OCI = Obsessive Compulsive Inventory; Dx = Diagnosis; SD = Standard Deviation

Zero-order Correlations and Descriptive Statistics

We calculated zero-order correlations, as well as means and standard deviations at Time 1. As can be seen in Table 2, drive for thinness was significantly, positively moderately correlated with overall OCD symptoms, checking, neutralizing, and obsessing, but not with hoarding, ordering, or washing. The strongest correlation was with obsessing. Bulimic symptoms was positively moderately correlated with overall OCD symptoms, hoarding, and obsessing, but not with checking, neutralizing, ordering, or washing. The strongest correlation was with hoarding, though obsessing was also high. Body dissatisfaction was positively moderately correlated with overall OCD symptoms, neutralizing, obsessing, and ordering, but not with hoarding, checking, or washing. The strongest correlation was with obsessing. Binge eating was only weakly correlated with obsessing, whereas purging was moderately correlated with all aspects except hoarding, namely checking, neutralizing, obsessing, ordering, and washing. Finally, fasting was moderately correlated with neutralizing, obsessing, and washing.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations for all Time 1 variables in Study 1.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mean (SD) |

23.21 (7.06) |

14.40 (7.83) |

43.16 (10.44) |

17.43 (8.47) |

3.94 (2.31) |

3.31 (2.04) |

0.19 (0.40) |

1.25 (1.64) |

17.76 (13.45) |

2.30 (2.52) |

2.04 (2.32) |

2.52 (3.22) |

4.33 (3.28) |

4.43 (3.50) |

2.13 (2.68) |

| 1. DriveThin | - | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Bulimia | .40** | - | |||||||||||||

| 3. BodyDis | .67** | .35** | - | ||||||||||||

| 4. EDEQ Overall | .83** | .52** | .76** | - | |||||||||||

| 5. Binge Eating | .81** | .48** | .76** | .87** | - | ||||||||||

| 6. Purging | .76** | .44** | .66** | .88** | .81** | - | |||||||||

| 7. Laxative Use | .14 | .68** | .05 | .27** | .20* | .17 | - | ||||||||

| 8. Fasting | .37** | .23* | .40** | .54** | .45** | .53** | .12 | - | |||||||

| 9. OCI Overall | .32** | .20* | .23* | .35** | .23* | .37** | .07 | .26** | - | ||||||

| 10. Checking | .20* | .15 | .07 | .19* | .06 | .21* | .10 | .15 | .82** | - | |||||

| 11. Hoarding | .19* | .32** | .07 | .16 | .14 | .17 | 21* | .08 | .55** | .37** | - | ||||

| 12.Neutralizing | .24* | .05 | .20* | .28** | .16 | .28** | −.02 | .25** | .83** | .64** | .27** | - | |||

| 13. Obsessing | .44** | .31** | .32** | .45** | .29** | .43** | .11 | .19* | .75** | .58** | .35** | .45** | - | ||

| 14. Ordering | .16 | .09 | .17 | .21* | .10 | .22* | −.06 | .17 | .86** | .64** | .27** | .76** | .53** | - | |

| 15. Washing | .15 | −.05 | .12 | .17 | .16 | .26** | −.06 | .24** | .73** | .51** | .36** | .53** | .38** | .56** |

Note. SD = Standard Deviation; DriveThin = Drive for Thinness; Bulimia = Bulimic Symptoms; BodyDis = Body Dissatisfaction; EDEQ = Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire; OCI = Obsessive Compulsive Inventory;

p < .05,

p < .01.

Unique Relationships with OCD symptoms

As can be seen in Table 3, obsessing was the only significant unique correlate of drive for thinness (with moderate effect size), as well as the EDE-Q global index. Obsessing and hoarding were the only significant unique correlates associated with bulimic symptoms. Obsessing and checking (negatively) were uniquely associated with body dissatisfaction. Obsessing and checking (negatively) were also uniquely associated with binge eating, and obsessing was uniquely correlated with purging. Hoarding was the only significant correlate of laxative use.

Table 3.

Multiple regression analyses predicting eating disorder symptomatology in sample 1.

| Predictors | β | Part r | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regression 1; OCD symptomatology predicting EDEQ Global | |||

| Checking | −.19 | −.12 | .144 |

| Hoarding | −.02 | −.02 | .818 |

| Neutralizing | .25 | .15 | .072 |

| Obsessing | .55** | .42** | <.001 |

| Ordering | −.16 | −.09 | .291 |

| Washing | .05 | .04 | .670 |

| Regression 2; OCD symptomatology predicting Drive for Thinness | |||

| Checking | −.13 | −.09 | .330 |

| Hoarding | .06 | .05 | .552 |

| Neutralizing | .24 | .16 | .085 |

| Obsessing | .52** | .38** | <.001 |

| Ordering | −.26 | −.15 | .091 |

| Washing | .04 | .03 | .765 |

| Regression 3; OCD symptomatology predicting Bulimia Symptoms | |||

| Checking | .05 | .04 | .700 |

| Hoarding | .30** | .27** | .004 |

| Neutralizing | −.04 | −.03 | .759 |

| Obsessing | .30* | .23* | .014 |

| Ordering | −.03 | −.02 | .847 |

| Washing | −.22 | −.17 | .061 |

| Regression 4; OCD symptomatology predicting Body Dissatisfaction | |||

| Checking | −.28* | −.19* | .044 |

| Hoarding | −.02 | −.18 | .850 |

| Neutralizing | .21 | .13 | .156 |

| Obsessing | .41** | .31** | .001 |

| Ordering | −.03 | −.02 | .845 |

| Washing | .02 | .02 | .861 |

| Regression 5; OCD symptomatology predicting Fasting | |||

| Checking | −.11 | −.07 | .428 |

| Hoarding | −.00 | −.00 | .990 |

| Neutralizing | .23 | .14 | .123 |

| Obsessing | .12 | .10 | .295 |

| Ordering | −.10 | −.06 | .519 |

| Washing | .20 | .16 | .081 |

| Regression 6; OCD symptomatology predicting Binge Eating | |||

| Checking | −.29* | −.19* | .031 |

| Hoarding | .00 | .00 | .989 |

| Neutralizing | .21 | .13 | .138 |

| Obsessing | .43** | .33** | <.001 |

| Ordering | −.15 | −.09 | .301 |

| Washing | .14 | .11 | .216 |

| Regression 7; OCD symptomatology predicting Purging | |||

| Checking | −.16 | −.11 | .196 |

| Hoarding | −.05 | −.04 | .627 |

| Neutralizing | .22 | .13 | .114 |

| Obsessing | .49** | .37** | <.001 |

| Ordering | −.17 | −.10 | .247 |

| Washing | .18 | .14 | .094 |

| Regression 8; OCD symptomatology predicting Laxative Use | |||

| Checking | .18 | .12 | .201 |

| Hoarding | .25* | .22* | .015 |

| Neutralizing | −.02 | −.01 | .875 |

| Obsessing | .09 | .07 | .441 |

| Ordering | −.21 | −.12 | .189 |

| Washing | −.12 | −.10 | .303 |

p < .05,

p < .01.

Prospective Analyses

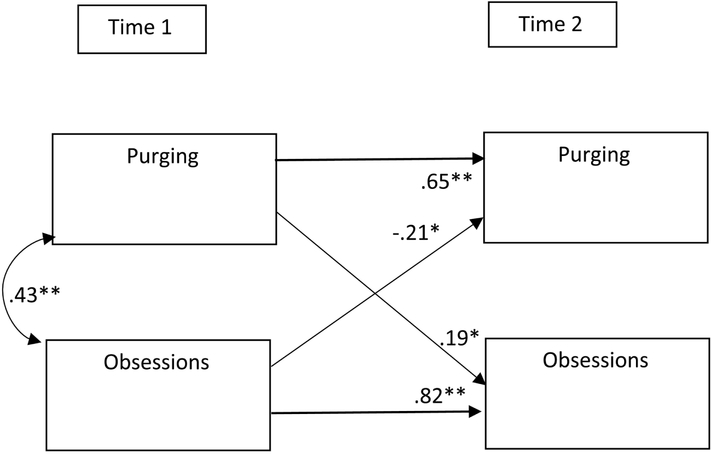

We tested if obsessing at Time 1 predicted ED behaviors (frequency of binge eating, purging, and fasting) at Time 2. Controlling for purging at Time 1, obsessing at Time 1 negatively predicted purging at Time 2, whereas purging at Time 1 (while controlling for obsessions at Time 1) positively predicted obsessing at Time 2 (see Figure 1). Obsessing did not predict fasting, though there was a moderate effect size, and fasting did not predict obsessing (ps > .058). Obsessing did not predict binge eating, and binge eating did not predict obsessing (ps > .14).

Figure 1.

Prospective relationships between obsessions and purging. *p < .05. **p < .001

Preliminary Discussion

First, as expected, these data supported that there were no significant differences between individuals with AN or Atypical AN on any aspect of OCD, suggesting that OCD symptoms are as high in individuals with Atypical AN as in AN. We also found that obsessions were the cognitive-behavioral aspect of OCD that was most related to ED symptoms, across the majority of ED domains. Specifically, obsessing was related to overall ED symptoms, drive for thinness, bulimic symptoms, body dissatisfaction, binge eating, and purging. No other domain of OCD was uniquely associated with the majority of ED outcomes. This finding suggests that OCD cognitions, rather than behaviors (e.g., checking, washing) may be the most related to ED symptoms.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, we found that prospectively, obsessing significantly (negatively) predicted purging, whereas purging positively predicted obsessing. These prospective findings show how the cycle of obsessions and purging operate over time. Specifically, one possible conclusion is that purging serves as a safety behavior. (i.e., temporary relief creating longer term distress), and therefore, higher purging leads to higher obsessing over time. For example, in OCD, handwashing is a safety behavior to prevent obsessions/fears around getting sick. Similarly, purging may function as a behavior that keeps an individual ‘safe’ from fears of gaining weight. At first, it may seem counterintuitive that obsessing negatively predicts purging. However, this finding fits with the function of obsessive thoughts in OCD (Laposa, Hawley, Grimm, Katz, & Rector, 2018), such that individuals who are able to sit with high levels of obsessions report later lower levels of safety behaviors (in this case, purging). However, future research is needed to determine the exact mechanism that is driving this negative relationship. We hypothesize that it may be the ability to tolerate obsessions without acting on safety behaviors/compulsions.

Though these data provide a preliminary test of OCD symptoms in an AN and Atypical AN sample, there were several limitations. Primarily, the usage of a self-report diagnostic interview was a limitation because it is not as valid as interview diagnostic tools (e.g., Fairburn & Beglin, 1994). For example, there are many limitations to utilizing self-report specifically to diagnose Atypical AN. For example, it is possible that people diagnosed with atypical AN and recently discharged from treatment [within the past year] should have a diagnosis of AN and only receive atypical AN because they have recently received treatment and are weight restored. Therefore, in a second study, we utilized a structured clinical interview to determine diagnosis to test if our results replicated with more precise assessment of diagnosis. We hypothesized that there would be no differences between those individuals diagnosed with AN versus Atypical AN, replicating Study 1 findings. We also hypothesized that we would replicate the finding that obsessing was the aspect of OCD most related to ED symptoms and behaviors.

Study 2: Methods

Participants

Participants were 115 individuals with a current ED diagnosis of either AN (n = 36) or Atypical AN (n = 79). 64 participants (55.7%) reported that they were currently in some form of treatment for their ED. Specifically, 55 participants (47.8%) were in outpatient treatment, 3 participants (2.6%) were in intensive outpatient, 2 participants were in partial hospitalization (1.7%), and 4 participants (3.5%) were in inpatient or residential treatment. Participants median time in treatment is 4.92 hours (SD = 31.07) a week.

The majority of participants were female (n = 113; 98.3%) and White (n = 101; 87.8%). Other ethnicities reported include multiracial or biracial (n = 4; 3.5%), Hispanic (n = 5; 4.3%), Black (n = 2; 1.7%), and Indian/Indian American (n = 1; .09%). Two participants did not report their ethnicity. Participants ranged in age from 16 to 47 years old, with an average age of 26.76 (SD = 6.56).

Measures

Diagnostic Interviews.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Eating Disorder Module. (SCID-5; First, Williams, Karg, & Spitzer, 2016).

The SCID-5 is a semi-structured interview used for making standardized DSM-5 diagnoses. The research version (SCID-5-RV) includes modules for mood disorders, psychotic disorders, substance use disorders, anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorders, feeding and eating disorders, and trauma and stress disorders. Questions address subtype, severity, and course specifiers for these disorders. For the purpose of this study, only the ED modules were used.

Eating Disorder Diagnostic Interview. (EDDI; Nobakht & Dezhkam, 2000).

The EDDI is a 31-item measure based on the diagnostic criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Version-IV (DSM-IV) and derived from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III (SCID). The EDDI is used to examine frequency and intensity of ED symptoms over the course of the previous year. It includes items that assess ED behaviors (e.g. binging/ purging, laxative/diuretic use, fasting), cognitions (e.g. fear of fatness; importance of weight and shape in self-evaluation), and physiological factors (e.g. amenorrhea, lowest and highest weights). The EDDI has been shown to have excellent test-retest reliability (Nobakht & Dezhkam, 2000).

Self-report Measures.

We used the EDI-2 and EDE-Q as in Study 1. Internal consistencies of the EDI-2 subscales were adequate to good (αs ranged from .81 to .92). Internal consistencies of the EDEQ restraint (α = .84), eating concerns (α = .78), weight concerns (α = .79), and shape concerns (α = .90) subscales ranged from adequate to good. We also used the OCI-R which is an abbreviated version of the OCI (as used in Study 1). The internal consistencies of the washing (α = .84), obsessing (α = .87), ordering (α = .92), checking (α = .81), and neutralizing (α = .86) subscales, as well as the OCI total (α = .91), were acceptable-to-good. The internal consistency of the hoarding (α = .69) subscale was poor.

Procedure

This study was approved by the University of Louisville Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited from research databases of alumni from ED treatment centers, online, and through fliers and advertisements. Participants were recruited to participate in an online treatment study. As the study was conducted completely online and over the phone, participants from several different countries across the globe were recruited. The participants hence represent a widely generalizable sample. The data used here was drawn from the screening assessment and baseline self-report measures before completing treatment. All data was cross-sectional, as follow-ups were not available. Participants completed two structured clinical interviews via phone or teleconference to determine diagnosis with a highly trained interviewer at either the PhD, MA, or BA level. All diagnoses were double-checked by two independent raters. Participants then completed online measures of ED symptoms and OCD symptoms. Participants were excluded from participation if they were actively manic, psychotic, or suicidal.

Diagnostic Procedure.

While both structured clinical interviews (SCID-5 and EDDS) were given, we primarily used the SCID-5 to determine diagnosis. The EDDS was only used as a supplemental interview to provide additional clarification on binge-eating and purging symptoms and for participants not included in this manuscript that had a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder. Additionally, participants were asked during the SCID-5 about both past and present AN to determine if the person had ever been underweight (and when) and therefore would have met criteria for AN (instead of Atypical AN). We only include participants here with Atypical AN who did not have a past diagnosis of AN within the past year to distinguish between partially recovered AN and Atypical AN. We had diagnostic agreement on 93% of cases, 7% of cases were re-reviewed by the PI (Dr. Levinson) when not in agreement and discussed with consensus to reach a final agreement on diagnosis.

Results

Diagnoses and Clinical Characteristics

The following diagnoses were made based on the SCID-5 (First et al., 2015) and EDDI (Stice et al., 2000): AN (n = 36) or Atypical AN (all symptoms of AN with the exception of the below 18.5 BMI; n = 79). Mean body mass index (BMI) was 20.54 (Range = 12.59-38.41; SD = 4.40). 25 participants reported having comorbid OCD (21.7%). Other self-reported diagnoses were anxiety disorders (n = 85; 73.9%), depressive disorders (n = 70; 60.9%), post-traumatic stress disorder (n = 25; 21.7%) attention deficient disorder or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (n = 4; 3.5%), borderline personality disorder (n = 5; 4.3%), and bipolar disorder (n = 6; 5.2%).

AN versus Atypical AN

Regarding demographics characteristics there were no significant differences between AN and Atypical AN on psychotropic medication use, sex, or current ED treatment (ps > .137). There was a significant difference on age, with Atypical AN participants reporting slightly younger ages t(113) = 2.19, p = .027 (M1 =28.75, SD = 6.67; M2 = 25.85, SD = 6.34). Therefore, we include age in subsequent regressions.

Regarding OCD dimensions, the only significant difference between AN and Atypical AN was on the ordering subscale, with participants with Atypical AN scoring slightly higher than those with AN.

Zero-Order Correlations

As can be seen in Table 4, the same pattern of correlations was seen as in Study 1. Obsessing was significantly moderately correlated with all the ED outcomes, with the exception of bulimic symptoms, laxative use, and fasting.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations for all Time 1 variables in Study 2.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mean (SD) |

32.66 (6.63) |

18.41 (8.63) |

43.26 (8.71) |

14.95 (5.02) |

4.08 (2.05) |

3.80 (1.76) |

0.37 (.49) |

1.84 (1.95) |

22.43 (13.82) |

1.13 (1.02) |

1.03 (.89) |

0.99 (1.16) |

1.80 (1.16) |

1.70 (1.24) |

0.87 (1.02) |

| 1. DriveThin | - | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Bulimia | .42** | - | |||||||||||||

| 3. BodyDis | .63** | .18 | - | ||||||||||||

| 4. EDEQ Overall | .84** | .48** | .56** | - | |||||||||||

| 5. Binge Eating | .78** | .38** | .67** | .70** | - | ||||||||||

| 6. Purging | .78** | .39** | .61** | .79** | .72** | - | |||||||||

| 7. Laxative Use | .23* | .76** | .15 | .39** | .33** | .21* | - | ||||||||

| 8. Fasting | .42** | .34** | .28** | .56** | .42** | .38** | .26** | - | |||||||

| 9. OCI Overall | .41** | .16 | .36** | .44** | .32** | .44** | .03 | .25** | - | ||||||

| 10. Checking | .29** | .19* | .12 | .26** | .23* | .32** | .08 | .20* | .72** | - | |||||

| 11. Hoarding | .24* | .38** | .10 | .38** | .14 | .20* | .30** | .17 | .52** | .33** | - | ||||

| 12.Neutralizing | .37** | .07 | .43** | .39** | .31** | .47** | −.11 | .22* | .78** | .46** | .25** | - | |||

| 13. Obsessing | .37** | .15 | .29** | .41** | .28** | .36** | .02 | .12 | .69** | .32** | .28** | .42** | - | ||

| 14. Ordering | .28** | .05 | .22* | .26** | .15 | .28** | −.03 | .08 | .83** | .55** | .27** | .63** | .48** | - | |

| 15. Washing | .11 | −.14 | .31** | .16 | .17 | .17 | −.06 | .27** | .64** | .36** | .17 | .39** | .31** | .44** | - |

Note. SD = Standard Deviation; DriveThin = Drive for Thinness; Bulimia = Bulimic Symptoms; BodyDis = Body Dissatisfaction; EDEQ = Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire; OCI = Obsessive Compulsive Inventory;

p < .05,

p < .01.

Multiple Regression Analyses

As can be seen in Table 5, multiple regression analyses generally replicated what was found in Study 1. Replicating our findings in the first study, obsessing was found to be the only significant unique correlate (with moderate to strong effect sizes) of drive for thinness. Interestingly, washing (negatively) and hoarding were significantly, uniquely correlated with bulimic symptoms. Neutralizing was the primary unique correlate of body dissatisfaction. Obsessing was a unique correlate of binge eating and purging (as in Study 1), whereas hoarding was a unique correlate of laxative use.

Table 5.

Multiple regression analyses predicting eating disorder symptomatology in sample 2.

| Predictors | β | Part r | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regression 1; OCD symptomatology predicting EDEQ Global Score | |||

| Washing | −.06 | −.05 | .524 |

| Checking | −.01 | .00 | .960 |

| Ordering | −.18 | −.12 | .139 |

| Obsessing | .35** | .28** | .001 |

| Hoarding | .30** | .27** | .001 |

| Neutralizing | .29* | .21* | .011 |

| Age | .22* | .21* | .012 |

| Regression 2; OCD symptomatology predicting Drive for Thinness | |||

| Washing | −.10 | −.09 | .303 |

| Checking | .11 | .09 | .328 |

| Ordering | −.06 | −.04 | .628 |

| Obsessing | .30** | .24** | .007 |

| Hoarding | .13 | .12 | .185 |

| Neutralizing | .23 | .17 | .060 |

| Age | .14 | .13 | .158 |

| Regression 3; OCD symptomatology predicting Bulimia symptoms | |||

| Washing | −.28** | −.24** | .006 |

| Checking | .15 | .12 | .180 |

| Ordering | −.15 | −.10 | .254 |

| Obsessing | .16 | .13 | .133 |

| Hoarding | .40** | .37** | <.001 |

| Neutralizing | .04 | .03 | .743 |

| Age | .02 | .02 | .854 |

| Regression 4; OCD symptomatology predicting Body Dissatisfaction | |||

| Washing | .19 | .16 | .061 |

| Checking | −.13 | −.11 | .226 |

| Ordering | −.20 | −.13 | .129 |

| Obsessing | .19 | .16 | .066 |

| Hoarding | .00 | .00 | .965 |

| Neutralizing | .47** | .34** | <.001 |

| Age | .14 | .13 | .126 |

| Regression 5; OCD symptomatology predicting Fasting | |||

| Washing | .21* | .19* | .047 |

| Checking | .07 | .05 | .564 |

| Ordering | −.26 | −.17 | .065 |

| Obsessing | .08 | .07 | .454 |

| Hoarding | .16 | .15 | .110 |

| Neutralizing | .17 | .12 | .185 |

| Age | .13 | .12 | .188 |

| Regression 6; OCD symptomatology predicting Binge Eating | |||

| Washing | .02 | .02 | .845 |

| Checking | .10 | .08 | .367 |

| Ordering | −.27* | −.18* | .045 |

| Obsessing | .28* | .23* | .013 |

| Hoarding | .09 | .08 | .363 |

| Neutralizing | .28* | .20* | .027 |

| Age | .11 | .10 | .272 |

| Regression 7; OCD symptomatology predicting Purging | |||

| Washing | −.06 | −.05 | .529 |

| Checking | .12 | .09 | .263 |

| Ordering | −.17 | −.11 | .188 |

| Obsessing | .25* | .21* | .015 |

| Hoarding | .06 | .06 | .505 |

| Neutralizing | .41** | .30** | .001 |

| Age | .12 | .11 | .178 |

| Regression 8; OCD symptomatology predicting Laxative Use | |||

| Washing | −.09 | −.08 | .387 |

| Checking | .06 | .04 | .641 |

| Ordering | −.09 | −.06 | .552 |

| Obsessing | .08 | .07 | .474 |

| Hoarding | .39** | .36** | <.001 |

| Neutralizing | −.17 | −.12 | .182 |

| Age | .04 | .04 | .682 |

p < .05,

p < .01.

Discussion

The current study tested if there were differences between AN and Atypical AN in the occurrence of OCD cognitive and behavioral symptom dimensions. Additionally, we tested which cognitive-behavioral dimensions of OCD were most related to AN pathology. Overall, we found that there were very few significant differences between AN and Atypical AN in regards to OCD dimensions. Specifically, across two samples, the only significant difference in one sample was on the ordering subscale. These results are important because they show that regardless of BMI, OCD symptoms are non-differentially elevated in both AN and Atypical AN populations. Although some studies have found that the remission rate for individuals with Atypical AN is higher compared to individuals with AN (e.g., Silen et al., 2015), other studies have found that there are few differences in terms of severity of symptoms, psychiatric comorbidity, and medical complications between AN and Atypical AN (Mairs & Nicholls, 2016; Mustelin, Lehtokari, & Keski-Rahkonen, 2016; Sawyer et al., 2016; Whitelaw et al., 2014). In addition, AN and Atypical AN have shared genetic risk and similar age of onset (Fairweather-Schmidt & Wade, 2014; Hammerle, Huss, Ernst, & Burger, 2016). This study adds to the growing literature comparing a clinical diagnosis of AN versus Atypical AN and suggests, at least for OCD symptoms, there are no major differences.

Second, our findings suggest that obsessing is a particularly salient dimension of OCD that is uniquely associated with AN pathology. This finding is important because obsessing is a cognitive dimension of OCD, whereas the other OCD dimensions assessed were behavioral. Therefore, our findings suggest that cognitive dimension of OCD, rather than behavioral, may be the most related to AN pathology. It is possible that other ED behaviors, such as purging or laxative use serve a similar function to traditionally conceptualized OCD behaviors, and that may account for why we found that the cognitive domain was most related. We hope future research will test this theory.

We should also note that both hoarding (with BN symptoms) and neutralizing (body dissatisfaction) were also unique correlates. However, obsessing most frequently emerged as the most pertinent dimension of OCD overall. Obsessions are the tendency to have intrusive or repeated thoughts about a specific subject (Abramowitz, Taylor, & McKay, 2009). It makes sense that obsessions may be the dimension of OCD that is most related to ED symptoms, given that repetitive negative thinking is highly common in those with AN (Cowdrey & Park, 2011; Seidel et al., 2016). Furthermore, many individuals with AN report intrusive ED thoughts and mention these cognitions as one of the most disturbing symptoms of their illness (Cowdrey & Park, 2011; Smith, Mason & Lavender, 2018). The current study is interesting because it suggests that troubling thoughts in general, not limited to cognitions around weight and shape, may also be predictive of ED symptoms.

Indeed, we found that across time, obsessing significantly (negatively) predicted purging, while purging positively predicted obsessing. Though the negative relationship between obsessions and purging may seem counterintuitive, it may be that these prospective relationships represent a cycle of obsessions and compulsions (or safety behaviors) reminiscent of the function of obsessions and compulsions in OCD. In OCD, the ability to sit with obsessions (and therefore report higher obsessions) leads to less engagement in compulsions (in this case purging; Laposa et al., 2018). Therefore, this finding suggests that teaching patients to tolerate intrusive thoughts may decrease engagement in purging. Alternatively, more purging leads to more obsessing. Thus, educating clients on the fact that purging will increase disturbing cognitions over time may be a motivating factor to minimize purging behaviors. Clearly, future research is needed to determine the exact mechanism behind these relationships. However, this research is a first step in showing how obsessions and ED behaviors function over time.

The current study had several limitations. We had a primarily female sample, which limits our generalizability of our results to males with AN. Furthermore, though we did include structured clinical interviews for EDs, we did not use a structured interview approach to assess OCD. We also had a small sample of participants who self-reported having a diagnosis of OCD. Future research is needed to test if these results would hold in an all comorbid OCD-AN sample. However, given that OCD symptoms occur at a high rate, even without a clinical diagnosis in individuals with AN (e.g., Srinivasagam et al., 1995), our results begin to provide information on these symptoms specifically in an AN and Atypical AN sample. Additionally, we did not assess duration of illness, which might impact both AN and OCD severity. We also attempted to best characterize and distinguish between AN vs Atypical AN, but there are currently no guidelines on how to best categorize between these different diagnoses. For example, we were unable to determine if there was relapse to sub-threshold AN when there was a past history of full-threshold AN and whether this diagnosis is different from atypical AN. We hope future research will continue to clarify the difference between AN and Atypical AN and how to best diagnostically capture these disorders. Finally, the internal consistency of the hoarding subscale was low and therefore results capturing this dimension should be interpreted with care.

Overall, we found that there were almost no differences in OCD symptom dimensions between an AN and Atypical AN sample (with the exception of ordering in one sample). Furthermore, we found that obsessing was the dimension of OCD most frequently related to AN symptoms of drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, binge eating, and purging. These findings begin to characterize the complex relationship between AN and OCD symptoms and pave the way for future research examining this highly common comorbidity, as well as future treatment development. For example, by better understanding the symbiotic relationship of AN and OCD symptoms, treatments could be developed that can intervene specifically on relevant OCD symptoms, which should improve overall anxiety management within ED populations.

Highlights.

Anorexia Nervosa (AN) and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) are highly comorbid

We tested which aspects of OCD are most relevant in AN and Atypical AN

Obsessing was most related to AN symptoms

There were no significant differences between AN and Atypical AN in OCD symptoms

Obsessions may need particular attention in treatments of comorbid AN-OCD

Acknowledgments.

This research was supported by T32 DA007261-25 to Washington University in St. Louis. We have no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abramowitz JS, Tyler S, & McKay D (2009). Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lancet, 374, 491–499. doi: 10.1002/wps.20251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Anttila V, Bulik-Sullivan B, Finucane HK, Walters RK, Bras J, Duncan L, … & Patsopoulos NA (2018). Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science, 360, 1–12. doi: 10.1126/science.aap8757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookings JB, & Wilson JF (1994). Personality and family-environment predictors of self-reported eating attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Personality Assessment, 63, 313–326. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6302_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos LM, Yoshimi NT, Simão MO, Torresan RC, & Torres AR (2015). Obsessive-compulsive symptoms among alcoholics in outpatient treatment: Prevalence, severity and correlates. Psychiatry Research, 229, 401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederlöf M, Thornton LM, Baker J, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, Rück C, Bulik CM, & Mataix-Cols D (2015). Etiological overlap between obsessive-compulsive disorder and anorexia nervosa: a longitudinal cohort, multigenerational family and twin study. World Psychiatry, 14, 333–338. doi: 10.1002/wps.20251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowdrey FA, & Park RJ (2011). Assessing rumination in eating disorders: Principal component analysis of a minimally modified ruminative response scale. Eating Behaviors, 12, 321–324. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies H, Liao P, Campbell IC, & Tchanturia K (2009). Multidimensional self reports as a measure of characteristics in people with eating disorders. Eating and Weight Disorders, 14, e84–e91. doi: 10.1007/BF03327804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, & Cooper Z (1993). The Eating Disorder Examination In Fairburn CG, & Wilson GT (Eds.), Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment (12th ed., pp. 317–360). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, & Beglin SJ (1994). Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16, 363–370. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairweather-Schmidt AK, & Wade TD (2014). DSM-5 eating disorders and other specified eating and feeding disorders: Is there a meaningful differentiation?. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41, 524–533. doi: 10.1002/eat.22257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Egea E, Worbe Y, Bernardo M, & Robbins TW (2018). Distinct risk factors for obsessive and compulsive symptoms in chronic schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine, 19, 1–8. doi: 10.1017/S003329171800017X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Williams JW, Karg RS, & Spitzer RL (2016). User's guide for the SCID-5-CV Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5® disorders: Clinical version. Arlington, VA, US: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Kozak MJ, Salkovskis PM, Coles ME, and Amir N (1998). The validation of a new obsessive-compulsive disorder scale: The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 10, 206–214. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.10.3.206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Huppert JD, Leiberg S, Langner R, Kichic R, Hajcak G, & Salkovskis PM (2002). The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory: Development and validation of a short version. Psychological Assessment, 14, 485–496. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.14.4.485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forney KJ, Brown TA, Holland-Carter LA, Kennedy GA, & Keel PK (2017). Defining “significant weight loss” in atypical anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50, 952–962. doi: 10.1002/eat.22717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner DM, Olmstead MP, & Polivy J (1983). Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 2, 15–34. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halmi KA, Tozzi F, Thornton LM, Crow S, Fichter MM, Kaplan AS, et al. (2005). The relation among perfectionism, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder in individuals with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 38, 371–374. doi: 10.1002/eat.20190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerle F, Huss M, Ernst V, & Burger A (2016) Thinking dimensional: prevalence of DSM-5 early adolescent full syndrome, partial and subthreshold eating disorders in a cross-sectional survey in German schools. BMJ Open, 6. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, Bulik CM, Kaye WH, Treasure J, & Tyson E (2009). Academy for Eating Disorders position paper: Eating disorders are serious mental illnesses. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 42, 97–103. doi: 10.1002/eat.20589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laposa JM, Hawley LL, Grimm KJ, Katz DE, & Rector NA (2018). What drives ocd symptom change during cbt treatment? Temporal relationships among obsessions and compulsions. Behavior Therapy, doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2018.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaSalle VH, Cromer KR, Nelson KN, Kazuba D, Justement L, & Murphy DL (2004). Diagnostic interview assessed neuropsychiatric disorder comorbidity in 334 individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 19, 163–173. doi: 10.1002/da.20009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson CA, Sala M, Fewell L, Brosof LC, Fournier L, & Lenze EJ (2018). Meal and snack-time eating disorder cognitions predict eating disorder behaviors and vice versa in a treatment seeking sample: A mobile technology based ecological momentary assessment study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 105, 36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce KH & Crowther JH (1999). The reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination—Self-Report Questionnaire Version (EDE-Q). International Journal of Eating Disorders, 25, 349–351. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mairs R, & Nicholls D (2016). Assessment and treatment of eating disorders in children and adolescents. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 101, 1168–1175. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas S, Plana MT, Castro-Fornieles J, Gassó P, Lafuente A, Moreno E, & … Lazaro L (2013). Common genetic background in anorexia nervosa and obsessive compulsive disorder: Preliminary results from an association study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47, 747–754. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, & Beumont PV (2004). Validity of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in screening for eating disorders in community samples. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42, 551–567. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00161-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustelin L, Lehtokari V, & Keski-Rahkonen A (2016). Other specified and unspecified feeding or eating disorders among women in the community. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 49, 1010–1017. doi: 10.1002/eat.22586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor H, Mountford V, & Brown G (2011). Beliefs about excessive exercise in eating disorders: The role of obsessions and compulsions. European Eating Disorders Review, 19, 226–236. doi: 10.1002/erv.1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobakht M, & Dezhkam M (2000). An epidemiological study of eating disorders in Iran. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 28, 265–271. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallister E, & Waller G (2008). Anxiety in the eating disorders: Understanding the overlap. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 366–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CB, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Joiner T, Crow SJ, Mitchell JE, … le Grange D (2007). Psychometric properties of the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire: Factor structure and internal consistency. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40, 386–389. doi: 10.1002/eat.20373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto A, Mancebo MC, Eisen JL, Pagano ME, & Rasmussen SA (2006). The Brown Longitudinal Obsessive Compulsive Study: Clinical Features and Symptoms of the Sample at Intake. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67, 703–711. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein CS, Pigott TA, Altemus M, L'Heureux F, Gray JJ, & Murphy DL (1993). High rates of comorbid OCD in patients with bulimia nervosa. Eating Disorders: The Journal of Treatment & Prevention, 1, 147–155. doi: 10.1080/10640269308248282 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer SM, Whitelaw M, Le Grange D, Yeo M, & Hughes EK (2016). Physical and psychological morbidity in adolescents with atypical anorexia nervosa. Pediatrics, 137, 1–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel M, Petermann J, Diestel S, Ritschel F, Boehm I, King JA, & … Ehrlich S. (2016). A naturalistic examination of negative affect and disorder-related rumination in anorexia nervosa. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25, 1207–1216. doi: 10.1007/s00787-016-0844-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silén Y, Raevuori A, Jüriloo E, Tainio V, Marttunen M, & Keski-Rahkonen A (2015). Typical versus atypical anorexia nervosa among adolescents: Clinical characteristics and implications for ICD-11. European Eating Disorders Review, 23, 345–351. doi: 10.1002/erv.2370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KE, Mason TB, & Lavender JM (2018). Rumination and eating disorder psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 61, 9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasagam NM, Kaye WH, Plotnicov KH, Greeno C, Weltzin TE, & Rao R (1995). Persistent perfectionism, symmetry, and exactness after long-term recovery from anorexia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 1630–1634. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.11.1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Telch CF, & Rizvi SL (2000). Development and validation of the eating disorder diagnostic scale: A brief self-report measure of anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder. Psychological Assessment, 12, 123–131. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Fisher M, & Martinez E (2004). Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale: Additional evidence of reliability and validity. Psychological Assessment, 16, 60–71. DOI: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.1.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Marti CN, & Rohde P (2013). Prevalence, incidence, impairment, and course of the proposed DSM-5 eating disorder diagnoses in an 8-year prospective community study of young women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 445–457. doi: 10.1037/a0030679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers BJ, Sarawgi S, Fitch KE, Dillon KH, & Cougle JR (2018). Six in vivo assessments of compulsive behavior: A validation study using the obsessive-compulsive inventory–revised. Assessment, 25(4), 483–497. https://doi-org.echo.louisville.edu/10.1177/1073191116654759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinbourne J, & Touyz S (2007) The co-morbidity of eating disorders and anxiety disorders: a review. European Eating Disorder Review, 15, 253–274. doi: 10.1002/erv.784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres AR, Cruz BL, Vicentini HC, Lima MP, & Ramos-Cerqueira AA (2016). Obsessive-compulsive symptoms in medical students: Prevalence, severity, and correlates. Academic Psychiatry, 40, 46–54. doi: 10.1007/s40596-015-0357-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitelaw M, Gilbertson H, Lee KJ, & Sawyer SM (2014). Restrictive eating disorders among adolescent inpatients. Pediatrics, 134, 758–764. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]