Abstract

Background:

Family-centered rounds (FCRs) provide many benefits over traditional rounds, including higher patient satisfaction, and shared mental models among staff. These benefits can only be achieved when key members of the care team are present and engaged. We aimed to improve patient engagement and satisfaction with our existing bedside rounds by designing a new FCR process.

Methods:

We conducted a needs assessment and formed a multidisciplinary FCR committee that identified appointment-based family-centered rounds (aFCRs) as a primary intervention. We designed, implemented, and iteratively refined an aFCR process. We tracked process metrics (rounds attendance by key participants), a balancing metric (time per patient), and outcome metrics (patient satisfaction domains) during the intervention and follow-up periods.

Results:

After implementing aFCR, 65% of patients reported positive experience with rounds and communication. Rounds duration per patient was similar (9 versus 9.4 min). Nurse, subspecialist, and interpreter attendance on rounds was 72%, 60%, and 90%, respectively. We employed a Rounding Coordinator to complete the scheduling and communication required for successful aFCR.

Discussion:

We successfully improved our rounding processes through the introduction of aFCR with the addition of a rounding coordinator. Our experience demonstrates one method to increase multidisciplinary team member attendance on rounds and patient satisfaction with physician communication in the inpatient setting.

BACKGROUND/PROBLEM

Family-centered rounds (FCRs) are defined as interdisciplinary bedside rounds with the active participation by the patient and family in the development of the management plan.1,2 The American Academy of Pediatrics continues to recommend FCR as the standard of care for inpatient medicine.4,5

Multiple benefits stem from the incorporation of patient and family perspectives in medical decision-making during rounds.4 Families express a preference for participating in care discussions and report higher satisfaction levels with FCR.6–10 Nurses and hospital staff report that FCR foster a clearer understanding of medical plans and improve their capacity to help families.3 And perhaps most importantly, FCR has been associated with lower rates of harmful medical errors.11 Although trainees may have discrepant views and attitudes toward FCR, they can appreciate the role that FCR plays in their clinical training, and the benefit to families.12–14

The benefits of FCR can only be achieved when all members of the care team, including patients and families, are present and engaged. Coordination can be challenging, because family presence requires the family to know what time to expect the team and to be present. If nurses are to attend, the agreed upon time must not conflict with nursing hand-off or medication administration time. Consulting subspecialists and interpreters are additional key participants whose schedules must be considered. In addition, FCR processes must be considerate of competing demands such as educational conferences, transitions of care, and hospital-specific discharge times.

Our institution struggled with limited patient engagement and dissatisfaction with existing bedside rounds. We aimed to improve family engagement and satisfaction with inpatient rounds. Outpatient clinics successfully use appointments to provide structure and schedule framework for patient care. We hypothesized that revamping our morning rounding processes, with specific consideration of appointment-based family-centered rounding (aFCR), would help achieve the stated aim.

METHODS

Setting

UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital is an urban, academic quaternary care center with 183 beds and approximately 8,000 pediatric admissions annually. Approximately, 44% of our patient population is white (14% Hispanic or Latino), 16% black, 15% Asian, and 25% other race. Twelve percent of our inpatients have a preferred language other than English.

The Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) service is a non-intensive care unit team that cares for patients with a variety of medical and surgical diagnoses, excluding oncology, blood/marrow transplant, or solid organ transplant. During this intervention period, we had 2 PHM teams, each with a pediatric hospitalist on-service for 7 days in a row, a senior resident, 3 interns, and 1–2 medical students. The nurse-to-patient ratio was 1:3 or 1:4.

Stakeholders

The authors were asked by leadership to address issues of limited patient engagement and dissatisfaction with existing bedside rounds, as reflected in our Press Ganey surveys (Press Ganey Performance Solutions, South Bend, Ind.). Our primary stakeholders were patients, and secondary stakeholders were our leadership and frontline providers and staff, including PHM attendings, education leaders, learners (residents and medical students), nurses, case managers, social workers, dietitians, pharmacists, interpreter services, and child life specialists.

We formed a multidisciplinary FCR committee comprised of a rotating group of approximately 50 secondary stakeholders, with additional input from our Family Advisory Council. This committee met monthly over 9 months until we launched aFCR. Subsequently, the committee met on an ad-hoc basis.

Solution Identification

Team members shared perceptions of inadequate interprofessional communication, dissatisfaction with the lack of standardization of rounds, and nursing frustration with not being included in rounds. Subspecialist attendance on rounds was identified as desirable by both the trainees and the subspecialists, as it was often essential for medical decision-making.

The committee agreed that scheduled rounding appointments on our existing PHM service were a potential solution to many of the issues described above. The committee considered other solutions, including returning to subspecialist-led teams. However, our prior experience supported the value of hospitalists for residents’ experiences.16

Implementation and Iterative Refinement

Members of the committee educated residents, students, and nurses on new aFCR processes. We designed patient/family brochures and vetted them through our Family Advisory Council. The PHM Division Chief facilitated discussions with subspecialty divisions regarding these changes to rounds.

We officially launched aFCR on July 1, 2012. Initially, the daily rounding schedules were made by the unit-service coordinator (commonly called “unit clerk”). Early in the process, we identified several unanticipated issues: managing the appointments required significant time and skill, residents spent significant time communicating the appointment times to nurses and subspecialists, and rotating residents did not reliably communicate the workflow from one block to the next.

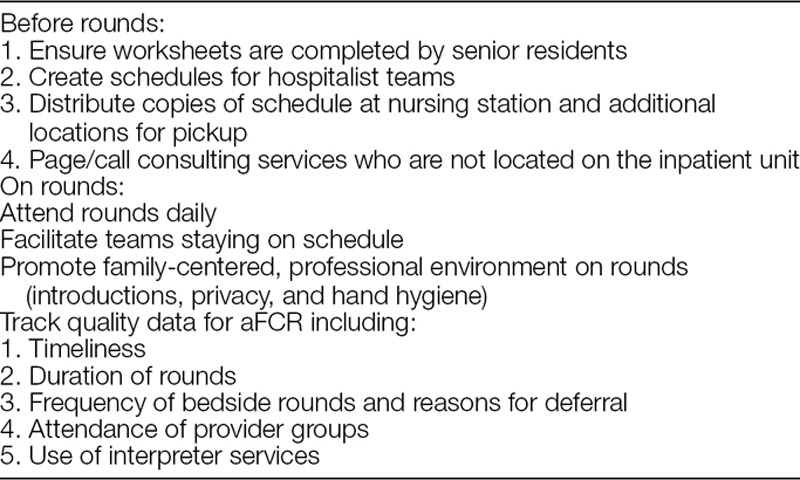

To address these issues, we designed a “Rounding Coordinator” 0.5 FTE position. This position, filled in October 2013, is charged with creating the daily rounding schedules and monitoring the quality and efficiency of aFCR (Table 1).

Table 1.

Responsibilities of Rounding Coordinator

Current Process

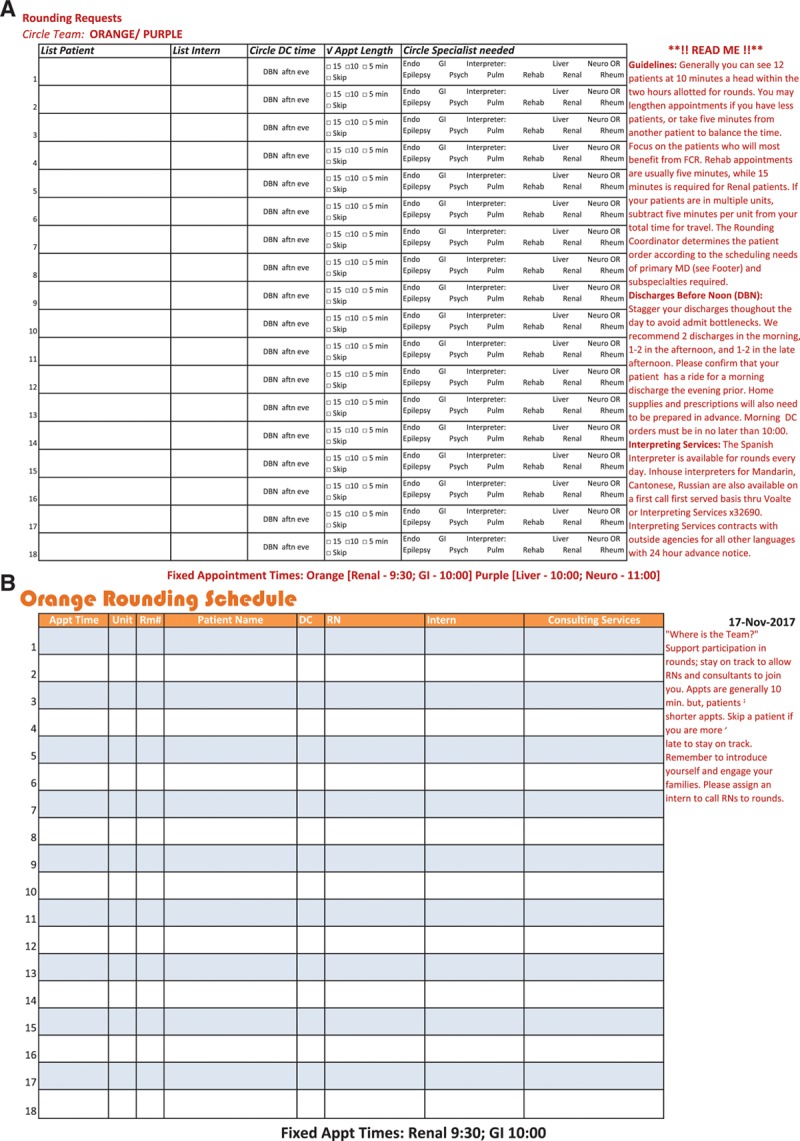

In our current process, senior residents complete a rounding worksheet (Fig. 1A) which lists the subspecialists and/or interpreters needed for each patient, and time needed for appointments (5/10/15 min). They complete this worksheet before 8 am, allowing the Rounding Coordinator time to create the rounding schedule (sample template in Fig. 1B) by 9 am. The rounding coordinator text-pages specialty consultants with their appointment schedule. We encouraged the nurses and interns to alert families to their specific rounding appointment time.

Fig. 1.

Rounding schedule templates. A, Rounding request template completed by senior residents. B, Final rounding schedule distributed to teams.

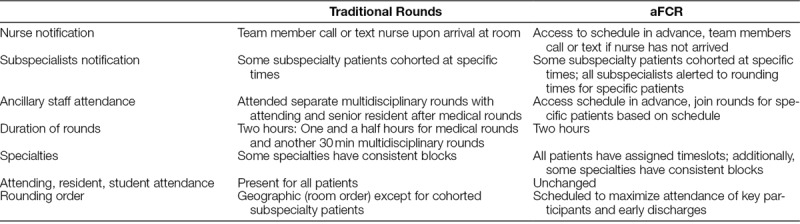

We summarize additional key elements of the aFCR intervention in Table 2.

Table 2.

Structure and Process Changes

Measurement of Impact

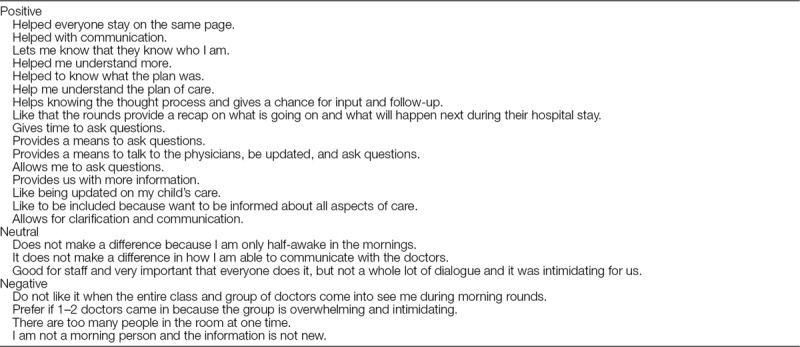

In the late 2012, 6 months after initiation of aFCR, the UCSF Patient Relations Department staff conducted qualitative bedside interviews with families about their experiences with rounds. We categorized comments as positive, negative, or neutral.

We measured family experience on our service using Press Ganey surveys, which utilize standardized, validated five-point Likert scale questionnaires. Scores are represented as an average score on a 0–100 scale, with each top score valued at 100, next score at 80, and continuing in 20-point decrements. We present our data in comparison to 111 hospitals in the Press Ganey national benchmark over 30 months (January 1, 2010 to June 30, 2012) before and 39 months (July 1, 2012 to September 30, 2015) after implementing aFCR.

During 2014–2015, the Rounding Coordinator documented process metrics: attendance of the bedside nurse, subspecialty consultants (when requested), and interpreter (when requested). The coordinator also documented rounding time per patient as a balancing measure.

This project met our institution’s definition of Quality Improvement and Quality Assurance activities not requiring Institutional Review Board review.

RESULTS

Outcome Measures

Fifty-two unique families shared their experience with aFCR via interviews (Table 3). Of these, 24/52 (65%) families reported a positive experience with aFCR. Fourteen (27%) reported a negative experience with aFCR. The remaining 5 (10%) reported neutral experiences.

Table 3.

Comments from Family Interviews

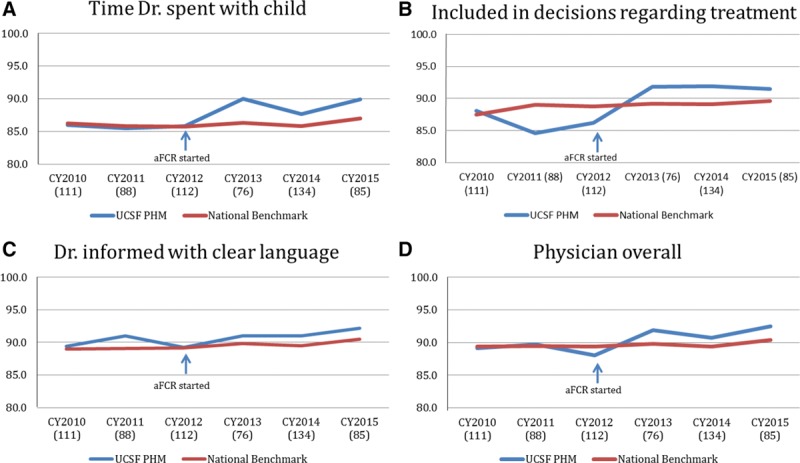

On average, one-hundred one (10%) Press Ganey surveys were returned annually. The results for specific items are displayed in Figure 2. Parent satisfaction for time spent, inclusion of parents, and overall physician rating were at or below the national benchmark preimplementation and increased postimplementation. Physician use of clear language remained relatively stable.

Fig. 2.

Press Ganey results for selected questions. A, The frequency with which families were always satisfied with time doctors spent with the child. B, Frequency with which doctors include families in decisions regarding treatment. C, The frequency with which doctors informed families using clear language. D, Aggregate mean percent for all physician domains on Press Ganey survey.

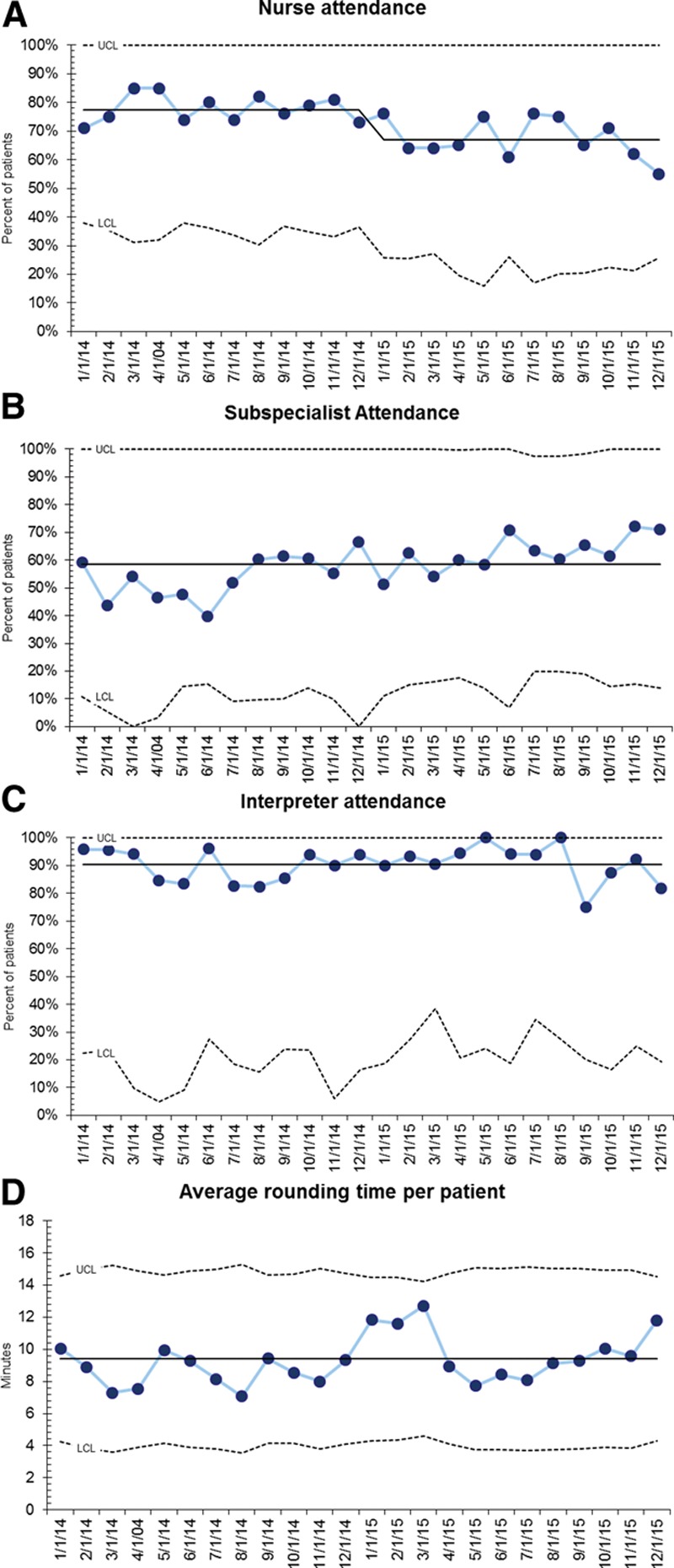

Process Measures

Before the implementation of aFCR, involvement of bedside nurses in daily rounds ranged from 30% to 40% attendance. We did not track other metrics before the intervention, but faculty retrospectively estimated that subspecialty consultants attended approximately 30% of the rounds when requested, varying by subspecialty and primarily for particularly challenging or complicated patient discussions. Interpreter presence at rounds was also rare (estimated to occur <30% of the time) before aFCR.

During the observation period, a bedside nurse attended 72% of aFCR (Fig. 2A). Nurse attendance decreased slightly during the second year, although this was also our first year in a new facility. On average, there were 5 subspecialists and 2 interpreter services requested per team per day. When requested, a subspecialty consultant and interpreter attended 60% and 90% of aFCR, respectively (Fig. 2B, C).

Statistical process control charts show the stability and sustainability of these process metrics in 24 months following the implementation of aFCR (Fig. 3). We have now sustained aFCR on our PHM service for 6 years.

Fig. 3.

Process metrics after implementation of aFCR. A,. Nurse attendance (% of patients for whom nurse was present). B, Subspecialist attendance (% of patients for whom subspecialist was present if requested). C, Interpreter attendance (% of patients for whom interpreter was present if requested). D, Average rounding time per patient (minutes).

Balancing Measure

We estimated a preintervention average rounding time per patient of 9 minutes, based on the standard length of rounds (90 min) divided by the average daily census (10 patients). After implementing aFCR, the average rounding time measured by direct observation was 9.4 minutes per patient (Fig. 2D).

DISCUSSION

We successfully implemented aFCR on a PHM service, and subsequently observed sustained improvements in both process and outcome measures. Family satisfaction surveys improved from below to above the national benchmark, with particularly strong improvements in family engagement domain. A majority of families reported positive experiences with aFCR, consistent with the extensive literature on FCR.6–10

Our aFCR process facilitated joint rounding by specialists and hospitalists. The defined appointments, together with pages/calls by the Rounding Coordinator, helped ensure that everyone’s time was used as efficiently as possible. When specialists are present on rounds, there is less need for postrounds communication, and families may view the physician providers as a unified team.

The Rounding Coordinator position was extremely well received and felt to be essential to the success of aFCR, and consequently is currently funded as a permanent position. The position requires approximately 0.5 full-time equivalent to complete both the intensive prerounds schedule work for our 2 inpatient teams, and the audit-and-feedback processes. Although this may be a large expense for a single medical unit, we felt the costs were easily offset by the benefits of improved efficiency for all team members, improved care coordination, and most importantly improved family-centered care and experiences.

It is noteworthy that family perception of the amount of time physicians spent with patients improved despite the minimal change in documented time. We suspect this is a halo effect, similar to documented improvements in patient–physician communication when physicians sit down with patients.17,18

Challenges

Our data show many positive patient and family experiences with aFCR. However, as in other studies,8,19 experiences were not uniformly positive. For the most part, the negative feedback related to the size of the team on rounds. This feedback led us to shift the conversation from “family centered” as a geographic notion to simply rounding in whatever manner the families prefer. We also employ other strategies such as a “ticket to round” for key team members, inviting the family outside and then seeing the child later in the day, etc.

With prescheduled rounding appointments, physicians had to learn new strategies for determining the allocation of time spent per patient. For example, new admissions, medical student presentations, and patients requiring interpreters typically required longer (15 min) appointments regardless of medical complexity.

Last-minute schedule changes inevitably occur, so we developed strategies for addressing these needs with minimum downstream effects on the schedule. Examples include rescheduling single appointments to get the team back on schedule (rather than being late to all subsequent appointments) and splitting the team when longer conversations were necessary but did not require all team members.

As part of ongoing curriculum evaluations, our residents and students have expressed concerns about teaching on aFCR, similar to others’ reports.12–14 This concern may be disproportionately driven by our appointment-based structure, as family-centered discussions often fill the entire appointment without leaving additional time for teaching. We addressed this by creating 5- or 10-minute “teaching appointments,” and by providing faculty development addressing teaching strategies on aFCR.

Limitations

Our report represents implementation on a single clinical service, which limits generalizability. Press Ganey surveys are generally felt to be representative of the entire hospitalization and thus they might not specifically represent the discussions on rounds. To address this issue, we focused on the subset of questions related to physician communication. Ideally, we would have established baseline levels of process measures. However, the sense of urgency in our institution, coupled with the lack of standard FCR processes, limited our ability to do so. Finally, we could not control for other concurrent interventions, including increased attention on patient satisfaction at a national and local level, improvements made to the discharge process, and hospital-specific goals (eg, The Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goals, others).

CONCLUSION

aFCR can be successfully implemented and may be associated with improvements in a variety of process measures, including attendance of rounds by nurses, consultants, and interpreters, and outcome measures including patient satisfaction. A rounding coordinator was a key element of our aFCR implementation. As academic medical centers implement or improve existing FCR processes, we recommend early engagement of all stakeholders, adequate administrative support for scheduling, and active monitoring with data feedback and quality improvement cycles.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the support of Joseph Pulsoni, our Rounding Coordinator.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Rosenbluth provided consulting work for the I-PASS Patient Safety Institute during 2016. The other authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

Footnotes

Published online May 23, 2019

To cite: Bekmezian A, Fiore DM, Long M, Monash BJ, Padrez R, Rosenbluth G, Sun KI. Keeping Time: Implementing Appointment-based Family-centered Rounds. Pediatr Qual Saf 2019;3:e182.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sisterhen LL, Blaszak RT, Woods MB, et al. Defining family-centered rounds. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19:319–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muething SE, Kotagal UR, Schoettker PJ, et al. Family-centered bedside rounds: a new approach to patient care and teaching. Pediatrics. 2007;119:829–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Committee on Hospital Care; American Academy of Pediatrics. Family-centered care and pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3 pt 1):691–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics. 2012;129:394–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landry M, Lafrenaye S, Roy M, et al. A Randomized, controlled trial of bedside versus conference-room case presentation in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2007;120:275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latta LC, Dick R, Parry C, et al. Parental responses to involvement in rounds on a pediatric inpatient unit at a teaching hospital: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2008;83:292–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aronson PL, Yau J, Helfaer MA, et al. Impact of family presence during pediatric intensive care unit rounds on the family and medical team. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1119–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuo DZ, Sisterhen LL, Sigrest TE, et al. Family experiences and pediatric health services use associated with family-centered rounds. Pediatrics. 2012;130:299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rea KE, Rao P, Hill E, et al. Families’ experiences with pediatric family-centered rounds: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2018;141: e20171883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mittal VS, Sigrest T, Ottolini MC, et al. Family-centered rounds on pediatric wards: a PRIS network survey of US and Canadian hospitalists. Pediatrics. 2010;126:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan A, Spector ND, Baird JD, et al. Patient safety after implementation of a coproduced family centered communication programme: multicenter before and after intervention study. BMJ. 2018;363:k4764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paradise Black NM, Kelly MN, Black EW, et al. Family-centered rounds and medical student education: a qualitative examination of students’ perceptions. Hosp Pediatr. 2011;1:24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox ED, Schumacher JB, Young HN, et al. Medical student outcomes after family-centered bedside rounds. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11:403–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinto JM, Chu D, Petrova A. Pediatric residents’ perceptions of family-centered rounds as part of postgraduate training. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014;53:66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burgis JC, Lockspeiser TM, Stumpf EC, et al. Resident perceptions of autonomy in a complex tertiary care environment improve when supervised by hospitalists. Hosp Pediatr. 2012;2:228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swayden KJ, Anderson KK, Connelly LM, et al. Effect of sitting vs. standing on perception of provider time at bedside: a pilot study. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:166–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merel SE, McKinney CM, Ufkes P, et al. Sitting at patients’ bedsides may improve patients’ perceptions of physician communication skills. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:865–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis C, Knopf D, Chastain-Lorber K, et al. Patient, parent, and physician perspectives on pediatric oncology rounds. J Pediatr. 1988;112:378–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]