Abstract

Background:

Hemolysis, even at low levels, activates platelets to create a prothrombotic state and is common during mechanical circulatory support. We examined the association of low level hemolysis (LLH) and non-hemorrhagic stroke during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA ECMO) support.

Methods:

A single center retrospective review of all adult patients placed on VA ECMO from January 2012 to September 2017 was conducted. To determine the association between LLH and non-hemorrhagic stroke, patients were categorized as those with and without LLH. LLH was defined by 48-hour plasma free hemoglobin (PFHb) of 11–50 mg/dL after VA ECMO implantation.

Results:

Of 201 patients who underwent VA ECMO placement, 150 (75%) met inclusion criteria and composed the study population. They were 55±14 years old and 50 (33%) were women. Sixty-two (41%) patients had LLH. Patients with LLH had a higher likelihood of incident non-hemorrhagic stroke during VA ECMO support (20[32%] vs. 4[5%]; aHR, 7.6; 95% CI, 2.2–25.9; P=0.001). The severity of LLH was associated with an incrementally higher likelihood of a non-hemorrhagic stroke (PFHb: 26–50 mg/dL, HR, 11.3; 95% CI, 3.6–35.1; P=0.001; PFHb: 11–25 mg/dL, HR, 4.4; 95% CI, 1.36–14.85, P=0.014), in comparison to no LLH. Those with LLH had a 2-fold greater increase in mean platelet volume after VA ECMO placement (0.98±1.1 vs. 0.49±0.96 fL, p=0.03). Patients with a non-hemorrhagic stroke had a higher operative mortality, (20[83%] vs. 57[45%]; adjusted hazard ratio, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.8–5.3; P<0.001).

Conclusions:

Hemolysis at low levels during VA ECMO support is associated with subsequent non-hemorrhagic stroke.

Exponential growth has occurred in the utilization of venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA ECMO) over the past decade for patients in refractory circulatory failure.1–3 This renewed interest is a result of improvements in cannula and pump technologies and the recognized advantage of rapid deployment in hemodynamically unstable patients refractory to initial medical interventions. Despite such expanding implementation of VA ECMO, outcomes remain stagnant with only 20–40% of patients surviving to discharge.4 Although survival is associated with various patient-related factors such as antecedent cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR),5 advanced age,3, 5 and end-organ function, it may also be influenced by device-induced, hemocompatability-related, adverse events such as bleeding and thrombosis.

Ischemic stroke has emerged as one of the most feared complications during VA ECMO support5,6,7; however, the pathophysiology and principal mechanisms leading to such a potentially devastating adverse event in this setting are poorly understood.5 We previously reported an association of low level hemolysis (LLH, i.e. plasma free hemoglobin 11–50 mg/dL) with future thromboembolic events such as pump thrombosis and ischemic stroke in patients on durable mechanical circulatory support (MCS).8 Such thrombotic events could be mediated by a hemolysis induced prothrombotic state, as hemolysate byproducts including plasma membranes and free hemoglobin from erythrocytes can induce platelet activation and aggregation.9 Indeed, in patients on durable MCS, a paradigm shift has occurred prompting device exchange in the setting of persistent moderate hemolysis prior to end-organ damage, thereby reducing ensuing stroke and death.10 Hemolysis also occurs during VA ECMO support, however, therapeutic intervention such as alteration of anticoagulation therapy, repositioning of the cannula or circuit exchange, is typically only considered in severe cases with a plasma free hemoglobin (PFHb) >100 mg/dL.11 Here, we investigated the association of early LLH at 48 hours after VA ECMO placement on subsequent non-hemorrhagic stroke.

Patients and Methods

Study Population

All patients with placement of VA ECMO from January 2012 to September 2017 at Montefiore Medical Center were reviewed retrospectively. Patients were supported by the RotaFlow centrifugal pump and the Maquet Quadrox oxygenator was used during VA ECMO support. To exclude peri-procedural events, patients on VA ECMO for <48 hours were excluded. In addition, those with unavailable hemolysis markers were not included in the study. This investigation was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Montefiore Medical Center.

Cannulation Techniques

For peripheral VA ECMO, a venous cannula (21–25 Fr) was inserted through the femoral vein with advancement of the tip into the right atrium. An arterial return cannula (16–18 Fr) was inserted in the femoral artery and positioned into the distal abdominal aorta. In addition, if suboptimal peripheral perfusion was suspected based on clinical exam, a distal perfusion cannula was connected to the side port of the arterial cannula and placed antegrade into the lower extremity or retrograde into a pedal artery. For central VA ECMO, aortic cannulation was done by a 18–20 Fr cannula and venous cannulation was performed by a 30–34 Fr cannula inserted into the right atrium.

ECMO management

Our usual approach is to aim for 2.2–2.5 L/min/m2 from VA ECMO support, titrated to optimal end organ perfusion, with at least intermittent aortic valve opening. Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump (IABP) or Impella to reduce afterload are placed if pulmonary edema ensues, particularly if the aortic valve is not opening and/or no pulsatility is observed on the arterial line. Oversight of the ECMO circuit is continuously provided by a trained perfusionist at the bedside with assistance from nurses in the intensive care unit. Patients are maintained on therapeutic unfractionated heparin or, when heparin induced thrombocytopenia is suspected or confirmed, on bivalirudin or argatroban. At our institution, therapeutic anticoagulation is achieved at a partial thromboplastin time of 50–70 seconds.

Clinical Data Collection

Baseline demographics and laboratory parameters were retrieved from medical charts. LLH was defined by serum PFHb of 11–50 mg/dL at 48 hours after VA ECMO placement. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was not utilized as a marker of hemolysis since it could be affected by tissue injury such as may have occurred during a myocardial infarction prior to VA ECMO placement. Change in mean platelet volume (MPV), a candidate marker for platelet activation,12, 13 was calculated from MPV values immediately before and after VA ECMO initiation. Non-hemorrhagic stroke was defined by i) the presence of new onset neurological symptoms that were confirmed by neurology consultation and ii) a corresponding acute cerebral infarction without the presence of hemorrhage noted on a head computed tomographic scan. Operative mortality was tracked up to 100 days after VA ECMO placement.

Statistical Analysis

Data were displayed as mean ± SD or counts (percent), unless otherwise indicated. Baseline demographic and laboratory parameters were compared between groups by the Student’s t test or Mann Whitney U test for continuous variables and by the Χ2 test for categorical variables. To evaluate the association of LLH and non-hemorrhagic stroke, patients were categorized as those with and without LLH. The primary outcome of non-hemorrhagic stroke was restricted to events diagnosed during VA ECMO support. Cumulative survival free from a non-hemorrhagic stroke during VA ECMO support was detailed using Kaplan-Meier curves; with censoring for death, explant, durable ventricular assist device placement, hemorrhagic stroke and diffuse anoxic brain injury. A log rank p-value was generated which represents the probability of differences between groups across the entire study period. Hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated using Cox proportional hazards models. Multivariable analysis was done for the association of LLH and non-hemorrhagic stroke with adjustment for covariates related with the exposure and outcome in univariable analyses at P<0.20, including age, atrial fibrillation, baseline creatinine and change in mean platelet volume (model 1). Two additional multivariable analyses were also computed with adjustment for fewer co-variables (model 2 adjusted for age, atrial fibrillation and model 3 adjusted for baseline creatinine and change in mean platelet volume). We further conducted cox regression analysis for PFHb as a continuous variable and its impact on non-hemorrhagic stroke with adjusted for age, atrial fibrillation, baseline creatinine and change in mean platelet volume (model 4). Lastly, an additional multivariable analysis was done for the association of a non-hemorrhagic stroke with operative mortality with adjustment for age and gender. Operative mortality was also analyzed for patients who did and did not have a stroke during VA ECMO support using Kaplan-Meier curves, which are censored for discharge. P values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient Characteristics

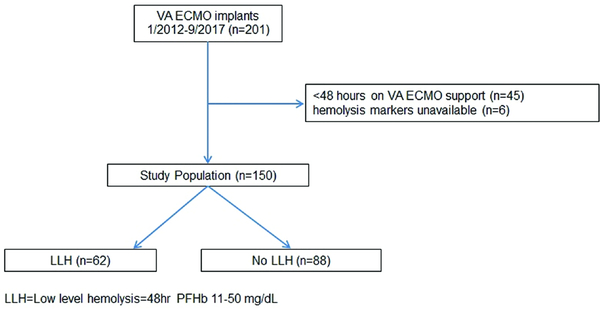

Of 201 patients who underwent VA ECMO placement, 150 (75%) met criteria and composed the study population (figure 1). The mean age of the study sample was 55±14 years old, and 50 (33%) patients were women. Ninety (60%) patients had a history of hypertension and 52 (35%) had diabetes mellitus. The major indication for VA ECMO placement was post cardiotomy shock (29%), followed by acute myocardial infarction (23%). At device placement, lactic acid was 8±5 mmoles/L. Overall, 73 (49%) patients survived to discharge.

Figure 1:

Flow chart showing inclusion and exclusion criteria utilized to make up the study population.

Non-Hemorrhagic Stroke

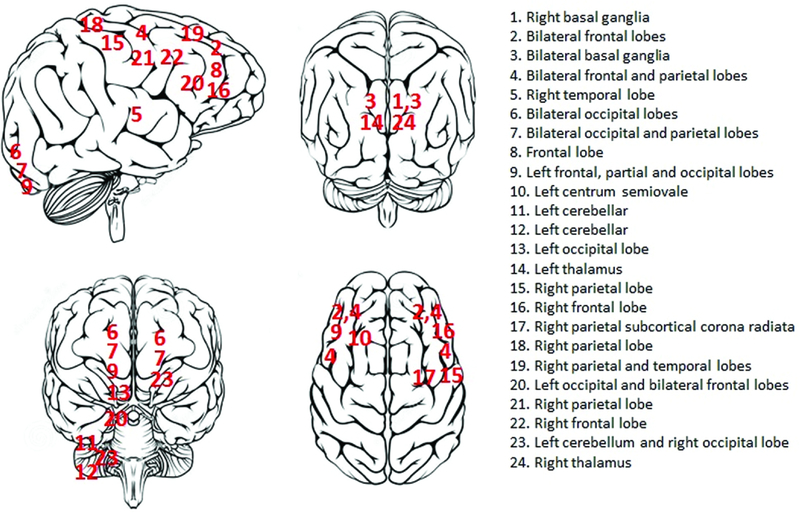

Twenty four (16%) patients had a non-hemorrhagic stroke during a total support period of 829 days. This yielded an event rate of 0.029 events per patient day (eppd) of support. The average time to a non-hemorrhagic stroke was 4±2 days after VA ECMO placement. At the time of non-hemorrhagic stroke, the partial thromboplastin time was in the therapeutic range at 58±15 seconds. The territorial distribution of non-hemorrhagic strokes is shown in figure 2; strokes appeared to occur diffusely throughout the brain without any preponderance for a specific cerebral territory. Table 1 shows that no differences were present in major demographics, laboratory parameters and implant indications between patients with and without a non-hemorrhagic stroke, except for PFHb (26 [15–42] vs. 7 [5–12] mg/dL, p<0.001) and LDH (1559 [847–3056] vs. 825 [486–1378] U/L, p=0.0009) levels at 48 hours after VA ECMO placement.

Figure 2:

Brain schematic showing the distribution of non-hemorrhagic strokes during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support.

Table 1:

Characteristics of patients with and without a non-hemorrhagic stroke.

| Non-hemorrhagic Stroke (n=24) | No Non-hemorrhagic Stroke (n=126) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 50±16 | 54±13 | 0.12 |

| Female, n (%) | 6 (25) | 44 (35) | 0.48 |

| BMI | 27±5 | 28±6 | 0.21 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| History of hypertension, n (%) | 13 (54) | 76 (60) | 0.73 |

| Diabetes Mellitus, n (%) | 12 (50) | 42 (33) | 0.58 |

| Coronary Artery Disease, n (%) | 6 (25) | 44 (35) | 0.48 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease, n (%) | 0 (0) | 8 (6) | 0.44 |

| Atrial Fibrillation, n (%) | 5 (20) | 20 (16) | 0.77 |

| COPD, n (%) | 1 (4) | 6 (5) | 0.68 |

| History of Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 3 (13) | 23 (18) | 0.67 |

| Laboratory Parameters | |||

| Baseline serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.6±2.8 | 1.9±1.9 | 0.19 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/BSA) | 48±36 | 49±31 | 0.95 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.5±1.7 | 10.2±2.5 | 0.97 |

| Platelet count (×1000/μl) | 173±100 | 159±99 | 0.54 |

| Change in mean platelet volume (fL) | 0.5±1 | 0.7±1.1 | 0.60 |

| Baseline lactic acid (mmoles/L) | 9.3±6.9 | 7.9±5.2 | 0.27 |

| 48-hr PTT (sec) | 53±13 | 56±22 | 0.57 |

| 48-hr Plasma free hemoglobin (mg/dL) | 26 [15–42] | 7 [5–12] | <0.001 |

| 48-hr Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 1559 [847–3056] | 825 [486–1378] | 0.0009 |

| Indication for VA ECMO | |||

| Graft failure after OHT, n (%) | 1 (4) | 19 (15) | 0.35† |

| Acute myocardial infarction, n (%) | 9 (38) | 26 (21) | |

| Post cardiotomy shock, n (%) | 9 (38) | 35 (28) | |

| Cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 3 (12) | 28 (23) | |

| Respiratory failure, n (%) | 1 (4) | 10 (8) | |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 1 (4) | 5 (4) | |

| Cardiac arrest, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (%) | 21±12 | 26±17 | 0.20 |

| Hemodynamics on VA ECMO | |||

| Mean Arterial Pressure (mmHg) | 76±9 | 78±12 | 0.64 |

| Central Venous Pressure (mmHg) | 11±7 | 12±5 | 0.37 |

| PA systolic pressure (mmHg)* | 29±6 | 32±12 | 0.46 |

| PA diastolic pressure (mmHg)* | 16±5 | 18±7 | 0.51 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump, n (%) | 9 (38) | 53 (42) | 0.85 |

| Impella, n (%) | 2 (8) | 10 (9) | 0.73 |

| Prosthetic heart valve, n (%) | 2 (8) | 19 (15) | 0.53 |

| Anti-platelets medications n (%) | 6 (25) | 39 (31) | 0.73 |

| VA ECMO characteristics | |||

| Peripheral cannulation, n (%) | 19 (79) | 114 (90) | 0.27†† |

| Central cannulation, n (%) | 4 (16) | 13 (10) | |

| Flow (L/min) | 3.96±0.98 | 3.98±0.99 | 0.93 |

| Unfractionated Heparin, n (%) | 23 (96) | 124 (98) | 0.97 |

| Duration of VA ECMO support (hours) | 141±55 | 131±73 | 0.55 |

| CPR before VA ECMO, n (%) | 11 (46) | 36 (29) | 0.15 |

COPD =chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; VA ECMO =venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; OHT =orthotopic heart transplant; PTT=partial thromboplastin time

only available for 70 patients

comparison for all indications

comparison for either central and peripheral cannulation

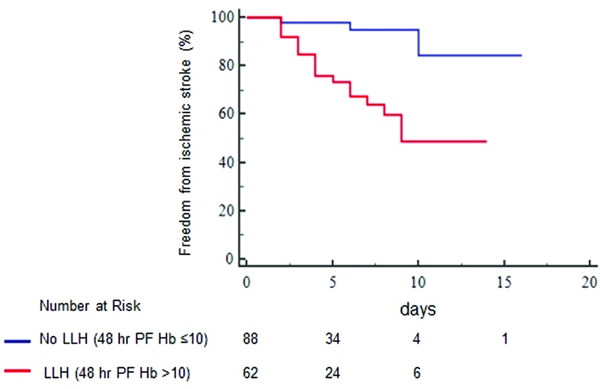

Association of LLH and Non-Hemorrhagic Stroke

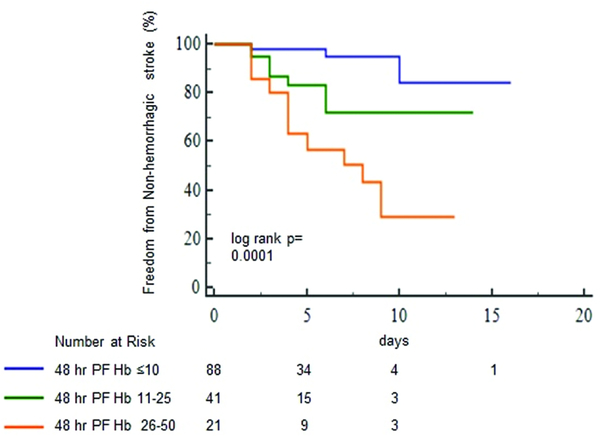

Sixty two (41%) patients had LLH (PFHb: 18 [12–34] mg/dL) and 88 (59%) did not have LLH (PFHb: 5 [3–7] mg/dL, p<0.0001) at 48 hours after VA ECMO placement. Table 2 shows that no differences were present in major demographics, laboratory parameters, and implant indications between patients with and without LLH. Twenty (32%, 0.055 eppd) patients with LLH had a non-hemorrhagic stroke in comparison to only 4 (5%, 0.008 eppd, log-rank P<0.001, figure 3) with no LLH. Those with LLH had a two-fold greater increase in MPV, a surrogate of platelet activation and aggregation,12 after VA ECMO placement (0.98±1.1 vs. 0.49±0.96 fL, p=0.03) in comparison to no LLH. After adjustment, LLH was associated with an increased risk of non-hemorrhagic stroke (model 1: aHR, 7.6; 95% CI, 2.2–25.9; P=0.001, table 3). In additional multivariable models, adjusted for fewer co-variables, LLH remained associated with non-hemorrhagic stroke (table 3). Moreover, the severity of LLH was associated with an incrementally higher likelihood of an eventual non-hemorrhagic stroke (log rank p=0.0001, figure 4). Those with a 48-hour PFHb of 26–50 mg/dL had a higher risk of a non-hemorrhagic stroke (aHR, 11.3; 95% CI, 3.6–35.1, P=0.001) than patients with a PFHb of 11–25 mg/dL (aHR, 4.4; 95% CI, 1.36–14.85, P=0.014), in comparison to no LLH. In continuous variable analysis, an increase by 1mg/dL of PFHb was related to a 6% higher risk of a non-hemorrhagic stroke. Despite omitting subgroups with potentially confounding mechanisms of stroke including those with post cardiotomy shock and antecedent CPR, there remained an association of LLH and eventual non-hemorrhagic stroke (HR, 4.5; 95% CI, 1.05–22.5, p=0.04).

Table 2:

Characteristics of patients with and without low level hemolysis (LLH*) 48 hours after VA ECMO placement.

| LLH (n=62) | No LLH (n=88) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 55±14 | 55±14 | 0.70 |

| Female, n (%) | 26 (42) | 24 (28) | 0.13 |

| BMI | 27±6 | 28±6 | 0.22 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| History of hypertension, n (%) | 36 (57) | 53 (61) | 0.77 |

| Diabetes Mellitus, n (%) | 24 (38) | 28 (32) | 0.56 |

| Coronary Artery Disease, n (%) | 16 (25) | 34 (39) | 0.25 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease, n (%) | 3 (5) | 5 (6) | 0.90 |

| Atrial Fibrillation, n (%) | 7 (11) | 18 (21) | 0.18 |

| COPD, n (%) | 1 (2) | 6 (7) | 0.26 |

| History of Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 12 (19) | 14 (16) | 0.79 |

| Laboratory Parameters | |||

| Baseline serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.3±2.3 | 1.9±1.9 | 0.26 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/BSA) | 49±36 | 48±27 | 0.80 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.3±2 | 10.1±2.6 | 0.68 |

| Platelet count (×1000/μl) | 165±92 | 150±105 | 0.73 |

| Change in mean platelet volume (fL) | 0.98±1.1 | 0.49±0.96 | 0.03 |

| Baseline lactic acid (mmoles/L) | 8.3±5.8 | 7.8±5.1 | 0.62 |

| 48-hr PTT (sec) | 55±19 | 56±23 | 0.66 |

| 48-hr Plasma free hemoglobin (mg/dL) | 18 [12–34] | 5 [3–7] | <0.0001 |

| 48-hr Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 1186 [639–2320] | 804 [493–1224] | 0.01 |

| Indication for VA ECMO | |||

| Graft failure after OHT, n (%) | 4 (6) | 16 (18) | 0.20† |

| Acute myocardial infarction, n (%) | 18 (29) | 17 (19) | |

| Post cardiotomy shock, n (%) | 20 (32) | 24 (29) | |

| Cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 12 (19) | 19 (22) | |

| Respiratory failure, n (%) | 5 (8) | 7 (8) | |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 4 (6) | 2 (2) | |

| Cardiac arrest, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | |

| Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (%) | 26±17 | 26±16 | 0.86 |

| Hemodynamics on VA ECMO | |||

| Mean Arterial Pressure (mmHg) | 77±10 | 77±12 | 0.96 |

| Central Venous Pressure (mmHg) | 12±6 | 12±5 | 0.82 |

| PA systolic pressure (mmHg)* | 32±14 | 31±9 | 0.98 |

| PA diastolic pressure (mmHg)* | 18±9 | 17±6 | 0.84 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump, n (%) | 24 (39) | 38 (43) | 0.61 |

| Impella, n (%) | 8 (13) | 6 (7) | 0.37 |

| Prosthetic heart valve, n (%) | 5 (8) | 16 (18) | 0.10 |

| Anti-platelets medications n (%) | 23 (37) | 21 (23) | 0.22 |

| VA ECMO characteristics | |||

| Peripheral cannulation, n (%) | 56 (90) | 77 (88) | 0.85†† |

| Central cannulation, n (%) | 7 (11) | 10 (11) | |

| Flow (L/min) | 3.9±1.0 | 4.1±0.9 | 0.22 |

| Duration of VA ECMO support (hours) | 137±74 | 130±68 | 0.51 |

| Unfractionated Heparin, n (%) | 61 (98) | 86 (98) | 0.77 |

| CPR before VA ECMO, n (%) | 20 (32) | 26 (30) | 0.90 |

low level hemolysis (LLH) =48-hour plasma free hemoglobin 11–50 mg/dL; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; VA ECMO =venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; OHT=orthotopic heart transplant; PTT=partial thromboplastin time

only available for 70 patients

comparison for all indications

comparison for either central and peripheral cannulation

Figure 3:

Freedom from a non-hemorrhagic stroke in patients with and without low level hemolysis (LLH). Censored for death, explant, durable ventricular assist device placement, hemorrhagic stroke and diffuse anoxic brain injury. PFHb indicates plasma free hemoglobin.

Table 3:

Hazard ratio estimates for a non-hemorrhagic stroke during low level hemolysis.

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 7.6 (2.2–25.9) | 0.001 |

| Model 2 | 7.7 (2.6–22.7) | 0.0002 |

| Model 3 | 11.8 (2.7–51.1) | 0.001 |

| Model 4 | 1.06 (1.02–1.11) | 0.006 |

Model 1: Adjusted for age, atrial fibrillation, baseline creatinine and change in mean platelet volume

Model 2: Adjusted for age, atrial fibrillation

Model 3: Adjusted for baseline creatinine and change in mean platelet volume

Model 4: Plasma free hemoglobin (mg/dL) analyzed as a continuous variable (adjusted for age, atrial fibrillation, baseline creatinine and change in mean platelet volume)

Figure 4:

Freedom from a non-hemorrhagic stroke in patients with differing severity of low level hemolysis (LLH). Censored for death, explant, durable ventricular assist device placement, hemorrhagic stroke and diffuse anoxic brain injury. PFHb indicates plasma free hemoglobin.

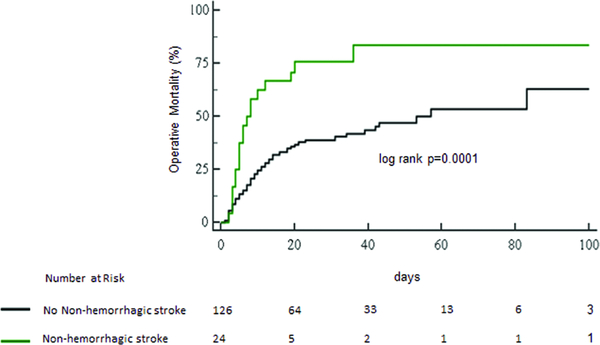

Non-Hemorrhagic Stroke and Mortality

Patient with a non-hemorrhagic stroke had a higher operative mortality (20[83%, 4.1 deaths per 100 post-operative days] vs. 57[45%, 1.5 deaths per 100 post-operative days], log-rank p<0.001, figure 5). After adjustment for age and gender, the risk of death was higher for patients who suffered a non-hemorrhagic stroke as compared to their counterparts who did not (adjusted hazard ratio, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.8–5.3; P=0.0001).

Figure 5:

Survival to discharge in patients who and did and did not experience a non-hemorrhagic stroke during venoarterial membrane oxygenation support.

Comment

We investigated the association of LLH after VA ECMO placement with subsequent non-hemorrhagic stroke. Our principal findings are as follows: First, early LLH is highly associated with an eventual non-hemorrhagic stroke during device support. Second, a higher degree of LLH severity portends a greater likelihood of a non-hemorrhagic stroke. Third, the rise in MPV, which may be an indication of platelet activation and aggregation,12 was higher in patients with LLH. And lastly, stroke is further related to poor survival. The observed associations were independent of covariates that showed possible univariable associations with non-hemorrhagic stroke. These associations are also unlikely to be confounded by variations in anticoagulation parameters since patients in both groups were on intravenous unfractionated heparin and reached similar partial thromboplastin times (PTTs) during device support. In addition, patients with and without LLH had similar demographics, indication and cannulation sites for VA ECMO and severity of baseline perfusion, as evidenced by similar lactic acid and serum creatinine levels. Although prior reports relate overt hemolysis (PFHb >50 mg/dL) with poorer survival11, 14, this is the first report to associate early LLH with non-hemorrhagic stroke. These findings thereby suggest LLH as not only a biomarker but a potentially novel therapeutic target for stroke prevention.

Hemolysis during VA ECMO support may occur, absent mechanical circuit issues, during instances of severe negative pressure with transient suction events (particularly during hypovolemia and at elevated speeds) leading to erythrocyte cavitation.15 In addition, microthrombus formation at a blood-pump interface may obstruct blood flow and promote red cell destruction. Once triggered, hemolysis can induce a prothrombotic state as hemolysate and free hemoglobin lead to platelet activation and aggregation.9 The diffuse cerebral locations of non-hemorrhagic stokes further implicates a potentially generalized prothrombotic state during LLH. Of note, mechanisms of hemolysis-induced thrombosis have been described in diseases of intravascular hemolysis such as sickle cell anemia (SCA).16 In such hemolytic disorders, free hemoglobin scavenges nitric oxide (NO), which leads to lower platelet cGMP, and prevents proteolysis of pro-thrombotic ultra-large (UL) multimers of von Willebrand factor (vWF) by the metalloproteinase, ADAMTS 13, resulting in increased platelet activation and aggregation.17–19 Although the incidence of hemolysis varies with device type, it remains universally prevalent in both durable and acute mechanical circulatory support devices (MCSDs). For instance, Impella, a short term percutaneous support device used during high risk percutaneous coronary interventions and to treat cardiogenic shock, is known to incur hemolysis and thrombotic adverse events.20, 21 Although, Impella during ECMO has been further associated with hemolysis severity,22 in our analysis both groups had similar PFHb levels on this device combination. We previously demonstrated that LLH at discharge is present in 1 out of every 3 patients with the Heart Mate 2 durable left ventricular assist device and associated with an increased risk of subsequent pump thrombosis or ischemic stroke. Interestingly, this elevated risk of pump thrombosis and ischemic stroke during LLH was reduced with concomitant administration of sildenafil, which enhances downstream NO signaling by preventing the breakdown of platelet cGMP by phosphodiesterase-5.8

In the current investigation, we found a strong association between LLH and non-hemorrhagic stroke during VA ECMO support. These findings need to be confirmed in larger multicenter studies with a higher number of outcome events, but suggest that LLH could serve as a clinically useful “hemo-compatibility gauge,” as well as a potential therapeutic target. Further mechanistic and clinical studies to describe the impact of LLH on increasing platelet activation and aggregation during VA ECMO support would be helpful in this regard. Together with previous data8, 10, these findings suggest the need to examine the effectiveness of LLH guided pharmacologic therapies to enhance NO signaling or mechanical interventions such as circuit exchange, as it is conceivable that such interventions might limit strokes and improve survival. This investigation has several limitations. Foremost, this study is limited by a retrospective design that can lead to information and selection bias. To ensure accuracy, we verified all stroke outcomes documented in the medical record with concurrent radiological studies. Because of the relatively low number of non-hemorrhagic strokes, the multivariable analysis could not be adjusted for all variables that may impact this outcome. In addition, given wide confidence intervals around the hazard ratio, the multivariable models may lack precision and should be interpreted with appropriate caution. Although, the study groups with and without LLH were quite similar in levels of covariates, there may be other, unmeasured or incompletely measured differences besides LLH that may increase the susceptibility of VA ECMO patients for non-hemorrhagic stroke. Although the specific root cause of LLH was not ascertained in this retrospective study, its downstream contribution to a potentially global prothrombotic state would have occurred irrespective of etiology. While it is conceivable that LLH could be a result of an early micro thrombus in the circuit, the aforementioned findings still implicate its role in propagation to clinical thrombotic events. It remains plausible that strokes may have occurred through other mechanisms in such critically ill patients even prior to VA ECMO placement or during cardiopulmonary bypass; however, patients with and without LLH were all exposed to such confounders and the association of LLH with non-hemorrhagic stroke persisted between those who did not undergo cardiac surgery and antecedent CPR. In addition, non-hemorrhagic strokes were only adjudicated to cases with new onset neurologic symptoms that corresponded to simultaneous brain imaging. Since follow up ended at the time of the first detectable non-hemorrhagic stroke, the impact of LLH on recurrent strokes was not assessed.

In conclusion, our data show that early LLH is associated with subsequent non-hemorrhagic stroke and poorer survival in patients undergoing VA ECMO placement. Although the present findings will require prospective replication in larger cohorts, these results support assessment of LLH, namely PFHb, as an early risk stratification biomarker of hemocompatability for incident non-hemorrhagic stroke in this population. The current findings also provide an impetus for mechanistic studies to evaluate the contribution of LLH to platelet activation during continuous flow MCS devices.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sauer CM, Yuh DD and Bonde P. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use has increased by 433% in adults in the United States from 2006 to 2011. ASAIO journal. 2015;61:31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stretch R, Sauer CM, Yuh DD and Bonde P. National trends in the utilization of short-term mechanical circulatory support: incidence, outcomes, and cost analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014;64:1407–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batra J, Toyoda N, Goldstone AB, Itagaki S, Egorova NN and Chikwe J. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in New York StateCLINICAL PERSPECTIVE: Trends, Outcomes, and Implications for Patient Selection. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2016;9:e003179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCarthy FH, McDermott KM, Kini V, Gutsche JT, Wald JW, Xie D, Szeto WY, Bermudez CA, Atluri P and Acker MA. Trends in US extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use and outcomes: 2002–2012. Seminars in thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2015;27:81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aubin H, Petrov G, Dalyanoglu H, Saeed D, Akhyari P, Paprotny G, Richter M, Westenfeld R, Schelzig H and Kelm M. A suprainstitutional network for remote extracorporeal life support: a retrospective cohort study. JACC: Heart Failure. 2016;4:698–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nasr DM and Rabinstein AA. Neurologic complications of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Journal of Clinical Neurology. 2015;11:383–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorusso R, Barili F, Mauro MD, Gelsomino S, Parise O, Rycus PT, Maessen J, Mueller T, Muellenbach R and Belohlavek J. In-hospital neurologic complications in adult patients undergoing venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: results from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry. Critical care medicine. 2016;44:e964–e972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saeed O, Rangasamy S, Selevany I, Madan S, Fertel J, Eisenberg R, Aljoudi M, Patel SR, Shin J and Sims DB. Sildenafil Is Associated With Reduced Device Thrombosis and Ischemic Stroke Despite Low-Level Hemolysis on Heart Mate II Support. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2017;10:e004222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tran PL, Pietropaolo M-G, Valerio L, Brengle W, Wong RK, Kazui T, Khalpey ZI, Redaelli A, Sheriff J and Bluestein D. Hemolysate-mediated platelet aggregation: an additional risk mechanism contributing to thrombosis of continuous flow ventricular assist devices. Perfusion. 2016;31:401–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levin AP, Saeed O, Willey JZ, Levin CJ, Fried JA, Patel SR, Sims DB, Nguyen JD, Shin JJ and Topkara VK. Watchful Waiting in Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Device Patients With Ongoing Hemolysis Is Associated With an Increased Risk for Cerebrovascular Accident or DeathCLINICAL PERSPECTIVE. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2016;9:e002896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan K, McKenzie D, Pellegrino V, Murphy D and Butt W. The meaning of a high plasma free haemoglobin: retrospective review of the prevalence of haemolysis and circuit thrombosis in an adult ECMO centre over 5 years. Perfusion. 2016;31:223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park Y, Schoene N and Harris W. Mean platelet volume as an indicator of platelet activation: methodological issues. Platelets. 2002;13:301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saeed O, Rangasamy S, Luke A, Patel S, Sims D, Shin J, Gil MR, Slepian M, Billett H and Goldstein D. Sildenafil Reduces Risk of Ischemic Stroke and Pump Thrombosis with Ongoing Low Level Hemolysis During Heart Mate II Support. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2017;36:S111–S112. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omar HR, Mirsaeidi M, Socias S, Sprenker C, Caldeira C, Camporesi EM and Mangar D. Plasma free hemoglobin is an independent predictor of mortality among patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toomasian JM and Bartlett RH. Hemolysis and ECMO pumps in the 21st century. Perfusion. 2011;26:5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gladwin MT and Sachdev V. Cardiovascular abnormalities in sickle cell disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012;59:1123–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rother RP, Bell L, Hillmen P and Gladwin MT. The clinical sequelae of intravascular hemolysis and extracellular plasma hemoglobin: a novel mechanism of human disease. Jama. 2005;293:1653–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villagra J, Shiva S, Hunter LA, Machado RF, Gladwin MT and Kato GJ. Platelet activation in patients with sickle disease, hemolysis-associated pulmonary hypertension, and nitric oxide scavenging by cell-free hemoglobin. Blood. 2007;110:2166–2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaer DJ, Buehler PW, Alayash AI, Belcher JD and Vercellotti GM. Hemolysis and free hemoglobin revisited: exploring hemoglobin and hemin scavengers as a novel class of therapeutic proteins. Blood. 2013;121:1276–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badiye AP, Hernandez GA, Novoa I and Chaparro SV. Incidence of hemolysis in patients with cardiogenic shock treated with Impella percutaneous left ventricular assist device. ASAIO Journal. 2016;62:11–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ouweneel DM, Eriksen E, Sjauw KD, van Dongen IM, Hirsch A, Packer EJ, Vis MM, Wykrzykowska JJ, Koch KT and Baan J. Impella CP versus intra-aortic balloon pump in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: the IMPRESS trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016:23127. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pappalardo F, Schulte C, Pieri M, Schrage B, Contri R, Soeffker G, Greco T, Lembo R, Müllerleile K and Colombo A. Concomitant implantation of Impella® on top of veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation may improve survival of patients with cardiogenic shock. European journal of heart failure. 2017;19:404–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]