Abstract

Background:

Limited research among adolescents and young adults (AYA) has assessed tobacco and marijuana co-use in light of specific products. We examined the patterns of past 30-day co-use of tobacco and marijuana products, and the product-specific associations among past 30-day use of these substances.

Methods:

Data from three school-based convenience samples of California AYA (aged 15–22) (Sample 1=3,008; Sample 2=1,419; Sample 3=466) were collected during 2016–2017. Proportions of past 30-day co-use of tobacco (e-cigarettes, cigarettes, hookah, cigars) and marijuana (combustible, vaporized, edible, blunt) were estimated. Multivariable logistic regression analyses examined associations between use of each tobacco and marijuana product for individual samples, then the pooled analysis calculated combined ORs.

Results:

In the three samples, 7.3–11.3% of participants reported past 30-day co-use. Combinations of e-cigarettes or cigarettes and combustible marijuana were the most common co-use patterns. Past 30-day use of e-cigarettes or cigarettes (vs. non-use) increased the odds of past 30-day use of all marijuana products [E-cigarettes: ORs (95%CI) ranging from 2.5 (1.7, 3.2) for edible marijuana to 4.0 (2.8, 5.2) for combustible marijuana; Cigarettes: from 3.2 (2.1, 4.2) for vaporized marijuana to 5.5 (3.8, 7.3) for combustible marijuana]. Past 30-day use of hookah or cigars was positively associated with past 30-day use of three of four marijuana products, except for hookah and vaporized marijuana, and for cigars and combustible marijuana.

Conclusions:

Given various co-use patterns and significant associations among tobacco and marijuana products, interventions targeting AYA should address co-use across the full spectrum of specific products for both substances.

Keywords: tobacco, cannabis, marijuana, substance use, youth, young adults

1. INTRODUCTION

Tobacco and marijuana use among adolescents and young adults (AYA) in the U.S. is a public health concern. Recent national data showed that 27.1% of high school students reported past 30-day use of any tobacco1 and 19.8% reported past 30-day use of any marijuana.2 Furthermore, several studies indicated that past 30-day co-use of two substances was higher than use of either tobacco or marijuana only among adolescents,3 and higher than use of marijuana only among young adults.4 The use of these substances during neurodevelopmental stages exposes AYA to numerous adverse health consequences and societal impacts (e.g., lifelong substance use disorders, poor education outcomes, mental and physical health problems).3,5,6

Understanding tobacco and marijuana co-use among AYA has become more important given the proliferation of new products. The tobacco landscape has shifted from conventional cigarettes to cigars/cigarillos, hookah, smokeless tobacco, and more recently, e-cigarettes.7 Marijuana is also available in a variety of combustible (e.g., joints, pipes, bongs, blunts), vaporized (e.g., electronic vaporizers), and edible products (e.g., candy, cookies).8 Co-use can refer to use of both substances separately across the aforementioned products during the past 30 days, or at the same time or in the same product, such as with blunts (cigar wrapper filled with marijuana).9 Recent studies have demonstrated a transformation of tobacco use patterns10–12 with the use of non-cigarette products (e.g., e-cigarettes, hookah) now surpassing conventional cigarette use among adolescents.1,13,14 In contrast, despite the appeal of newer marijuana products, combustible marijuana remains the most common form used across all age groups.15 Therefore, it is critical to characterize tobacco and marijuana co-use in light of specific products.

Past research on tobacco and marijuana co-use among AYA has predominantly focused on examining the overall relationship between tobacco and marijuana using “blanket terms” (e.g., any tobacco, any marijuana), or only co-use of combustible forms (i.e., cigarettes and combustible marijuana) and blunts.6,9,15,16 Newer co-use research among AYA has taken into account specific products.3,4,17,18 However, these studies have examined only the co-use of individual tobacco products with “any marijuana,” which limits our understanding on specific marijuana products co-used with tobacco. Only two recent studies have assessed co-use of specific products for both substances. One study among 1,420 high school students compared past 30-day use of cigarettes, cigars, hookah, and e-cigarettes between current blunt and combustible marijuana users.19 This study, however, focused on only combustible forms of marijuana; thus, it did not fill an important gap in the literature on alternative forms of marijuana (e.g., vaporized and edible products).15 The other study among 2,668 adolescents assessed the relationship between previous use of tobacco products (i.e., cigarettes, e-cigarettes, hookah) and subsequent use of marijuana products (i.e., combustible, vaporized, edibles).20 Although this study provided more insights by including non-combustible marijuana products, it did not directly provide data on past 30-day co-use of tobacco and marijuana products, and more importantly, did not include a sample of young adults, a group with the highest risk of co-use relative to other age groups.21 National data indicated co-use prevalence among young adults in 2014–2015 was 21.3%,4 and nearly half of adult co-users were between 18–25 years old.21 To our knowledge, there has been no research among young adults considering specific products for both tobacco and marijuana.

Given the current era of marijuana legislative reform nationwide as well as the proliferation of proposed national and state tobacco regulations, more research on co-use of tobacco and marijuana is needed to inform these actions. Since California has progressive tobacco control policies and recent legalization of marijuana, data on co-use of tobacco and marijuana among AYA in this state would provide evidence from a unique regulatory environment that is likely to represent where the rest of the country may be headed. Using three school-based convenience samples of California AYA (aged 15–22), we aimed to examine (1) the patterns of past 30-day co-use of tobacco (e-cigarettes, cigarettes, hookah, cigars) and marijuana products (combustibles, vaporized, edibles, blunts), and (2) the product-specific associations between past 30-day use of these substances.

2. METHODS

2.1. Data and samples

Since to our knowledge there have been no available population-based data for California AYA, we used cross-sectional data from three different longitudinal surveys, with a total of 4,893 AYA across California. Using the three samples allows for an increase in the demographic diversity of the participants, and for replicability across studies. Demographic characteristics of the three samples were provided briefly below (see Supplement Table 1 for more details).

2.1.1. Sample 1 (N=3,008)

Data were collected in 2017 among 12th grade students in Los Angeles, representing wave 8 of a longitudinal survey (the Happiness & Health Study).22 Ten public high schools were selected based on their interest in participating, demographic composition, and proximity to the research institute. Participants completed paper-and-pencil surveys administered in classrooms or surveys administered by telephone, Internet, or mail. The participation rate for wave 8 was 92.5% (3,140 of 3,396 persons who participated in wave 1 of the original survey). Of the participants who completed this wave, 2,967 participants (94.5%) had completed data for ever use of all tobacco and marijuana products and 3,008 participants (95.8%) had completed data for past 30-day use of all tobacco and marijuana products (mean age=17.9; 55.1% female; 47.8% Hispanic, 16.5% White, 4.8% Black).

2.1.2. Sample 2 (N=1,419)

Data were collected in 2016–2017 among participants in an ongoing prospective cohort study (Children’s Health Study) in 12 Southern California communities.23 Participants first completed surveys assessing substance use in 2014, when they were in 11th or 12th grade. Online surveys were completed for each follow-up wave, which took place after participants were age 18. The current analyses use data from wave 3 of the study. The participation rate for wave 3 was 71.6% (1,502 of 2,097 persons who participated in wave 1 of the original survey). Of the participants who completed this wave, 1,426 participants (94.9%) had complete data for ever use of all tobacco and marijuana products and 1,419 participants (94.5%) had complete data for past 30-day use of all tobacco and cannabis products (mean age=20.2; 53.2% female; 49.2% Hispanic, 37.9% White, 1.1% Black).

2.1.3. Sample 3 (N=466)

Data were collected in 2017 among participants in an ongoing longitudinal study (the Tobacco Perceptions Study) in Northern and Southern California.24 Participants first completed surveys assessing substance use in 2014, when they were in high school. Online surveys administered by Qualtrics (Provo, UT) were completed for each follow-up wave. The current analyses use data from wave 4 of the study. The participation rate for wave 4 was 67.9 % (524 of 772 persons who participated in wave 1 of the original survey). Of the participants who completed this wave, 472 participants (90.1%) had complete data for ever use of all tobacco and marijuana products, and 466 participants (88.9%) had complete data for past 30-day use of all tobacco and marijuana products (mean age=18.3; 59.4% female; 21.2% Hispanic, 26.2% White, 1.1% Black).

2.2. Ethics statement

Assent and consent forms were obtained from participants, and a parent or a legal guardian, respectively. Individual studies were approved by Institutional Review Boards at University of Southern California (Samples 1 and 2) and at Stanford University (Sample 3).

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Tobacco use

Participants were asked, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you use [cigarette, e-cigarette, cigar/cigarillo, and hookah]?” Each product was asked separately, and responses were coded dichotomously (“Not used in the past 30 days” vs. “Used at least 1 day in the past 30 days”).

2.3.2. Marijuana use

Participants were asked, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you use [combustible marijuana, vaporized marijuana, edible marijuana, and blunts]?” Each product was asked separately and coded similarly as tobacco use. Combustible marijuana was defined as smoked marijuana by joints, bowls, pipes, and bongs. Since blunts (marijuana rolled in tobacco leaf or cigar casing) is a combination of both tobacco and marijuana, it was categorized as a separate product, and was not included in combustible marijuana.

2.3.3. Past 30-day co-use of tobacco and marijuana

Past 30-day co-use was defined as use of any tobacco product along with any marijuana product within the past 30 days.

2.3.4. Demographic characteristics

Participants provided their age, gender (male or female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, Hispanic, and Other/Multi race), and educational attainment (e.g., 10th–12th grades, high school or equivalent, some college, associate or bachelor’s degree).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Since the original surveys varied in questionnaires and methodologies, three samples were analyzed separately using the same analytic procedures. Only participants with complete data on past 30-day use of all tobacco and marijuana products were included in the analyses. Unweighted frequencies and proportions (denominators = total sample sizes) were computed for each tobacco and marijuana product. A crosstab of past 30-day use of tobacco and marijuana products was used to describe frequencies and proportions of past 30-day co-use patterns. To examine product-specific associations, a multivariable logistic regression model for each marijuana product (a binary outcome) included all tobacco products (simultaneous regressors) and demographic variables (covariates). Estimates (odds ratios) of each product-specific association from individual samples were then combined by a pooling procedure for analysis of multiple studies using the command “metan” in STATA 15.0. All tests of hypotheses were two-tailed with a significance level of α less than 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Past 30-day use of any tobacco and marijuana

As shown in Table 1, in Samples 1, 2 and 3, proportions of marijuana-only use were the highest (13.9%, 15.0%, 15.2%; respectively), followed by co-use (9.9%, 11.3%, and 7.3%) and tobacco-only use (3.1%, 7.2%, 3.0%). Proportions of single-tobacco product use (8.5%, 11.6%, 6.4%) were higher than that of poly-tobacco product use (4.5%, 6.9%, 3.9%). On the other hand, poly-marijuana product use was more prevalent (17.7%, 18.7%, 14.8%) than single-marijuana product use (6.1%, 7.5%, 7.7%).

Table 1:

Past 30-day use of tobacco and marijuana among adolescents and young adults in California, 2016–2017

| Pattern of use N (%) |

Sample 1 (N=3,008) |

Sample 2 (N=1,419) |

Sample 3 (N=466) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco-only use | 92 (3.1) | 102 (7.2) | 14 (3.0) |

| Marijuana-only use | 417 (13.9) | 213 (15.0) | 71 (15.2) |

| Tobacco and Marijuana co-use | 299 (9.9) | 160 (11.3) | 34 (7.3) |

| Tobacco use | |||

| Single-product users | 256 (8.5) | 164 (11.6) | 30 (6.4) |

| Poly-product users (≥2 products) | 135 (4.5) | 98 (6.9) | 18 (3.9) |

| Three most common patterns | |||

| E-cigarette only | 152 (5.1) | 56 (3.9) | 21 (4.5) |

| Cigarette only | 60 (2.0) | 72 (5.1) | 6 (1.3) |

| (E-cigarette + Cigarette) only | 45 (1.5) | 25 (1.8) | 8 (1.7) |

| Marijuana use | |||

| Single-product users | 182 (6.1) | 107 (7.5) | 36 (7.7) |

| Poly-product users (≥2 products) | 534 (17.7) | 266 (18.7) | 69 (14.8) |

| Three most common patterns | |||

| Combustible marijuana only | 132 (4.4) | 83 (5.8) | 24 (5.2) |

| (Combustible marijuana + Blunt) only | 135 (4.5) | 61 (4.3) | 21 (4.5) |

| All four marijuana products | 169 (5.6) | 85 (6.0) | 16 (3.4) |

3.2. Past 30-day co-use of specific tobacco and marijuana products

Table 2 presents proportions of co-use patterns of specific tobacco and marijuana products in the total samples. For tobacco, e-cigarettes and cigarettes were the most commonly used products, while cigars were the least used product. Regarding marijuana, the combustible form was used the most, while the vaporized form was used the least. The most common co-use patterns in all three samples were combinations of e-cigarettes or cigarettes and combustible marijuana (5.4–7.1%).

Table 2:

Past 30-day co-use of tobacco and marijuana products among adolescents and young adults in California, 2016–2017

| Tobacco/Marijuana product, n (Total %) | Any marijuana | Combustible marijuana | Vaporized marijuana | Edible marijuana | Blunt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 (N=3,008) | 716 (23.8) | 659 (21.9) | 291 (9.7) | 343 (11.4) | 467 (15.5) | |

| Any tobacco | 391 (13.0) | 299 (9.9) | 289 (9.6) | 167 (5.6) | 160 (5.3) | 233 (7.7) |

| E-cigarette | 268 (8.9) | 206 (6.8) | 199 (6.6) | 126 (4.2) | 107 (3.6) | 155 (5.2) |

| Cigarette | 163 (5.4) | 135 (4.5) | 133 (4.4) | 82 (2.7) | 86 (2.9) | 118 (3.9) |

| Hookah | 95 (3.2) | 82 (2.7) | 82 (2.7) | 59 (2.0) | 58 (1.9) | 73 (2.4) |

| Cigar | 66 (2.2) | 60 (2.0) | 59 (2.0) | 44 (1.5) | 38 (1.3) | 52 (1.7) |

| Sample 2 (N=1419) | 373 (26.3) | 348 (24.5) | 155 (10.9) | 174 (12.3) | 205 (14.4) | |

| Any tobacco | 262 (18.5) | 160 (11.3) | 157 (11.1) | 79 (5.6) | 94 (6.6) | 96 (6.8) |

| E-cigarette | 132 (9.3) | 84 (5.9) | 81 (5.7) | 45 (3.2) | 47 (3.3) | 48 (3.4) |

| Cigarette | 153 (10.8) | 101 (7.1) | 101 (7.1) | 51 (3.6) | 68 (4.8) | 63 (4.4) |

| Hookah | 70 (4.9) | 44 (3.1) | 44 (3.1) | 23 (1.6) | 28 (2.0) | 28 (2.0) |

| Cigar | 58 (4.1) | 42 (3.0) | 42 (3.0) | 27 (1.9) | 32 (2.3) | 32 (2.3) |

| Sample 3 (N=466) | 105 (22.5) | 91 (19.5) | 38 (8.2) | 43 (9.2) | 52 (11.2) | |

| Any tobacco | 48 (10.3) | 34 (7.3) | 31 (6.7) | 18 (3.9) | 16 (3.4) | 22 (4.7) |

| E-cigarette | 36 (7.7) | 28 (6.0) | 25 (5.4) | 14 (3.0) | 13 (2.8) | 19 (4.1) |

| Cigarette | 20 (4.3) | 14 (3.0) | 14 (3.0) | 9 (1.9) | 8 (1.7) | 9 (1.9) |

| Hookah | 12 (2.6) | 10 (2.1) | 10 (2.1) | 6 (1.3) | 6 (1.3) | 10 (2.1) |

| Cigar | 3 (0.6) | 3 (0.6) | 3 (0.6) | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) |

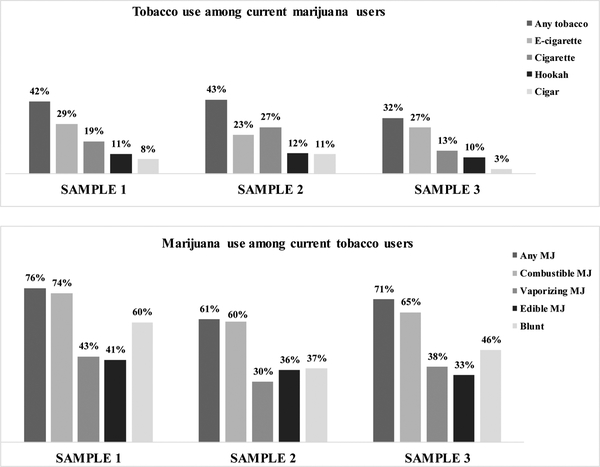

Figure 1 displays each of marijuana products used among only past-30-day tobacco users (not the total samples) and vice versa. Across the three samples, 76.5%, 61.1%, and 70.8% of past 30-day tobacco users were using any marijuana product. On the other hand, 41.8%, 42.9%, and 32.4% of past 30-day marijuana users were using any tobacco product.

Figure 1:

Past 30-day co-use of specific tobacco and marijuana products among adolescents and young adults in California, 2016–2017

3.3. Product-specific associations between past 30-day use of tobacco and marijuana

Table 3 presents the product-specific associations between past 30-day use of tobacco and marijuana for each sample and for the pooled analysis. After controlling for demographic characteristics (i.e., age, gender, race/ethnicity, educational attainment), past 30-day use of any specific tobacco product was generally positively associated with use of some or all marijuana products across the three samples. Combined, e-cigarette users had 2.5 (95%CI=1.7, 3.2) to 4.0 (95%CI=2.8, 5.2) times the odds of using all marijuana products as compared to non-users. Likewise, cigarette smokers (vs. non-smokers) were more likely to use all marijuana products, with ORs ranging from 3.2 (95%CI=2.1, 4.2) to 5.5 (95%CI=3.8, 7.3). Past 30-day use of hookah and cigars were also positively associated with past 30-day use of three of four marijuana products, except for the associations between hookah and vaporized marijuana, and between cigars and combustible marijuana.

Table 3:

Associations between past 30-day use of tobacco products and each marijuana product among adolescents and young adults in California, 2016–2017

| Tobacco product | Any marijuana | Combustible marijuana | Vaporized marijuana | Edible marijuana | Blunt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | ||

|

Sample 1 |

E-cigarette | 9.7 (6.9, 13.6) | 9.5 (6.8, 13.2) | 7.8 (5.5, 11.0) | 3.6 (2.6, 5.1) | 5.7 (4.1, 7.8) |

| Cigarette | 8.1 (5.0, 12.9) | 8.3 (5.2, 13.3) | 3.5 (2.3, 5.5) | 4.8 (3.2, 7.2) | 8.0 (5.3, 12.2) | |

| Hookah | 9.0 (4.6, 17.6) | 10.7 (5.4, 21.0) | 6.1 (3.5, 10.6) | 5.6 (3.3, 9.3) | 8.4 (4.7, 15.0) | |

| Cigar | 9.4 (3.6, 24.5) | 8.6 (3.4, 21.6) | 3.7 (1.8, 7.6) | 1.9 (1.0, 3.8) | 2.3 (2.0, 10.8) | |

|

Sample 2 |

E-cigarette | 3.2 (2.1, 4.9) | 3.0 (1.9, 4.6) | 2.6 (1.6, 4.3) | 1.8 (1.1, 3.0) | 1.8 (1.1, 3.0) |

| Cigarette | 4.4 (2.9, 6.6) | 4.9 (3.2, 7.3) | 2.9 (1.8, 4.7) | 5.2 (3.3, 8.0) | 3.3 (2.1, 5.1) | |

| Hookah | 2.2 (1.2, 4.0) | 2.4 (1.3, 4.4) | 1.6 (0.8, 3.0) | 1.9 (1.0, 3.6) | 1.8 (1.0, 3.4) | |

| Cigar | 2.7 (1.3, 5.4) | 2.8 (1.4, 5.6) | 2.8 (1.4, 5.4) | 3.0 (1.5, 6.0) | 3.5 (1.8, 6.8) | |

|

Sample 3 |

E-cigarette | 19.1 (6.1, 59.3) | 13.7 (4.8, 39.0) | 7.0 (2.4, 20.3) | 4.7 (1.6, 14.1) | 21.8 (7.0, 68.0) |

| Cigarette | 3.6 (0.8, 15.7) | 4.6 (1.1, 20.0) | 4.2 (1.0, 17.8) | 3.1 (0.7, 13.2) | 1.1 (0.2, 6.3) | |

| Hookah | 3.3 (0.5, 24.5) | 4.2 (0.6, 29.9) | 3.1 (0.5, 17.7) | 4.6 (0.8, 25.4) | 15.4 (1.7, 144.3) | |

| Cigar | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Combined | E-cigarette | 4.2 (2.9, 5.5) | 4.0 (2.8, 5.2) | 3.7 (2.5, 4.9) | 2.5 (1.7, 3.2) | 2.6 (1.8, 3.4) |

| Cigarette | 4.9 (3.3, 6.6) | 5.5 (3.8, 7.3) | 3.2 (2.1, 4.2) | 4.8 (3.4, 6.3) | 3.5 (2.3, 4.7) | |

| Hookah | 2.5 (1.2, 3.8) | 2.8 (1.3, 4.2) | 1.9 (0.9, 3.0) | 2.5 (1.3, 3.7) | 2.2 (1.01, 3.4) | |

| Cigar | 2.9 (0.9, 4.9) | 3.1 (0.98, 5.1) | 3.1 (1.4, 4.7) | 2.2 (1.1, 3.4) | 3.2 (1.1, 5.4) |

Note: Adjusted models controlling for gender, race/ethnicity, age, and educational attainment

4. DISCUSSION

Using 2016–2017 data from three demographically diverse California samples totaling 4,893 adolescents and young adults, we found that past 30-day co-use of tobacco and marijuana was common, with AYA using numerous different combinations of these substances. More importantly, those who used each tobacco product (i.e., e-cigarettes, cigarettes, hookah, cigars) were more likely to use some or all marijuana products (i.e., combustible-, vaporized-, edible marijuana, and blunts).

Notably, co-use of tobacco and marijuana in our samples was consistently higher than use of tobacco only, but less than use of marijuana only. This finding differs from previous studies, which found that either co-use was more prevalent than single substance use among youth during 2009–2014,3 or that co-use was more prevalent than marijuana-only use but less than tobacco-use only among young adults during 2014–2015.4 It should be noted that national data from these studies were from an earlier time period, and therefore may not capture the changes and secular trend in co-use or tobacco and marijuana products. In addition, there are regional variations in tobacco and marijuana regulations, and the findings from our California samples may reflect a unique regulatory environment with strong tobacco control policies but more marijuana normalization.18,25 Indeed, proportions of tobacco use across all our samples was less than national estimates,2,10 and proportions of marijuana use was higher than those reported from national surveys.2 Therefore, more research in other states is needed to unfold national average estimates of co-use.

Although our study focused on the co-use of marijuana and tobacco, we found an interesting result that the use of a single-tobacco product was more prevalent than the use of multiple tobacco products, while the poly-marijuana use was more popular than the use of a single-marijuana product. While the popularity of poly-marijuana use is consistent with prior research,26 the predominance of single-tobacco use seems in opposition to that reported previously.27 National data have documented that e-cigarette use has been the most commonly used tobacco products among adolescents since 2014.28 Since our data were collected during 2016–2017, we did find that exclusive e-cigarette use was the most common tobacco use pattern, which may reflect the recent transformation of tobacco use patterns among AYAs.

Our study stands out by characterizing co-use in light of specific products for both tobacco and marijuana, notably the inclusion of under-studied forms of marijuana (i.e., vaporized and edible products). We found that combinations of e-cigarettes or cigarettes and combustible marijuana were the most common patterns of co-use. This result is not surprising given the popularity of these products found in our samples, as well as in other national and state data.10,11,17,29 In addition to these common patterns, we also found that the co-use happened in all combinations across the spectrum of tobacco and marijuana products, including alternative or less common forms of two substances. Regarding product-specific associations, current use of each specific tobacco product was positively associated with some or all of the marijuana products in our study. This finding is in line with several recent studies,19,20 suggesting that not only popular forms of tobacco (i.e., cigarettes, e-cigarettes) but also alternative forms (i.e., hookah, cigars) increase the use of marijuana among AYA. However, the associations between hookah and vaporized marijuana and between cigar and combustible marijuana were not statistically significant. Since our samples were school-based convenience samples, these non-significant associations may be due to sample features. For example, small numbers of hookah and cigar users may limit our power to examine these associations. Additionally, small proportions of Black AYA may impact our findings related to cigars, since this subgroup is more likely to use cigars.2 More representative data are warranted to replicate our findings.

While the current literature provides reasons for co-use of tobacco and marijuana in general, it may also help to explain co-use of specific products. Existing research revealed that the same routes of administration and the similarities in product appearance (e.g., marijuana joints look like cigarettes, similar electronic products can be used to vaporize both nicotine and marijuana) may explain the crossover between combustible and vaporized forms of these substances.30 A qualitative study among young adults also described distinct reasons for co-use depending on the type of tobacco products used with combustible marijuana. For example, cigarettes were used with marijuana to enhance the synergistic effects (e.g., feeling “high”), hookah was used with marijuana in most social settings (e.g., parties), e-cigarettes were mainly used as a substitution or a means of lessening marijuana use, and cigars were used to roll blunts.31 Collectively, specific products should be considered in both research and practice of substance use prevention.

The exponential growth of emerging tobacco products (e.g., e-cigarettes) among adolescents coupled with the increasing legalization of marijuana nationwide make studying co-use of tobacco and marijuana a timely issue.32,33 This issue is even more important for California since the state is considered as the largest marijuana market in the US.34 Furthermore, the 2018 state report indicated that approximately 790,000 California adolescents had reported past-30 day co-use of tobacco and marijuana.35 The prevalence of marijuana use and co-use with tobacco may be partly due to AYA’s perceptions of harm related to marijuana and tobacco products.24,36,37 Marijuana is widely viewed as harmless or even good for health, and consistently perceived as more socially acceptable and less risky than tobacco.36 Moreover, AYA perceive a risk gradient with respect to tobacco, with cigarettes rated as most risky, followed by cigars and chew, with hookah and e-cigarettes rated as least risky.24,37 Given our finding that co-use was more prevalent than tobacco-only use, educational programs and interventions should address (mis)perceptions related to both tobacco and marijuana products to reduce the use of both substances among AYA.

This study is subject to several limitations. Since our samples were school-based convenience samples, the findings may not be representative of the California AYA population. The findings may not generalize to other states that have fewer tobacco control policies and less marijuana normalization than California. We could not establish causal relationships between tobacco and marijuana use due to the cross-sectional design. Additionally, our self-reported data were not biochemically verified and did not include information on several uncommon products (e.g., smokeless tobacco, spliff, synthetic marijuana). Finally, due to our measures of past-30-day use, we were unable to assess temporal specificity of co-use, such as use of tobacco and marijuana products at the same time or sequentially (one right before or after the other) on the same occasion.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Given various co-use patterns and significant associations among tobacco and marijuana products, interventions targeting AYA should address co-use across the full spectrum of specific products for both substances.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Examine co-use of combustible, vaporized, and edible forms of marijuana and tobacco

Past 30-day use of marijuana only was the most common (14–15%)

Past 30-day co-use of tobacco and marijuana was greater than tobacco use alone

Adolescents and young adults used numerous combinations of marijuana and tobacco

Use of each tobacco product increased the likelihood of use of all marijuana forms

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the following grants: the NIH/National Cancer Institute (NCI) (T32 CA113710); the NIH/NCI and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (1P50CA180890; U54CA180905; P50CA180905); the NIH/NHLBI and FDA (U54 HL147127 ); the NIH/National Institute on Drug Abuse (1K01DA042950; R01DA033296); and the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP 27IR-0034). The marginal cost of adding in the marijuana questions and writing this paper for Sample 3 was supported by Dr. Halpern-Felsher’s funding through Stanford University. The funders had no role in the design or conduct of the study, including the data collection, data management, analyses, interpretation of the data, or the manuscript preparation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, the FDA, or TRDRP.

Role of Funding Sources

This research was supported by the following grants: the NIH/National Cancer Institute (NCI) (T32 CA113710); the NIH/NCI and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (1P50CA180890; U54CA180905; P50CA180905); the NIH/NHLBI and FDA (U54 HL147127); the NIH/National Institute on Drug Abuse (1K01DA042950; R01DA033296); and the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP 27IR-0034). The marginal cost of adding in the marijuana questions and writing this paper for Sample 3 was supported by Dr. Halpern-Felsher’s funding through Stanford University. The funders had no role in the design or conduct of the study, including the data collection, data management, analyses, interpretation of the data, or the manuscript preparation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, the FDA, or TRDRP.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose. Robert Urman began a position at Amgen on April 15, 2019 and did not contribute to the paper after that date.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Gentzke AS, Apelberg BJ, Jamal A, King BA. Notes from the Field: Use of Electronic Cigarettes and Any Tobacco Product Among Middle and High School Students - United States, 2011–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(45):1276–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(8):1–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schauer GL, Peters EN. Correlates and trends in youth co-use of marijuana and tobacco in the United States, 2005–2014. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;185:238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohn AM, Abudayyeh H, Perreras L, Peters EN. Patterns and correlates of the co-use of marijuana with any tobacco and individual tobacco products in young adults from Wave 2 of the PATH Study. Addict Behav. 2019;92:122–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azofeifa A, Mattson ME, Grant A. Monitoring Marijuana Use in the United States: Challenges in an Evolving Environment. JAMA. 2016;316(17):1765–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramo DE, Liu H, Prochaska JJ. Tobacco and marijuana use among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review of their co-use. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(2):105–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connor RJ. Non-cigarette tobacco products: what have we learnt and where are we headed? Tob Control. 2012;21(2):181–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schauer GL, King BA, Bunnell RE, Promoff G, McAfee TA. Toking, Vaping, and Eating for Health or Fun: Marijuana Use Patterns in Adults, U.S., 2014. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schauer GL, Rosenberry ZR, Peters EN. Marijuana and tobacco co-administration in blunts, spliffs, and mulled cigarettes: A systematic literature review. Addict Behav. 2017;64:200–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang TW, Gentzke A, Sharapova S, Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Jamal A. Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students - United States, 2011–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(22):629–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson AL, Collins LK, Villanti AC, Pearson JL, Niaura RS. Patterns of Nicotine and Tobacco Product Use in Youth and Young Adults in the United States, 2011–2015. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(suppl_1):S48–S54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasza KA, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, et al. Tobacco-Product Use by Adults and Youths in the United States in 2013 and 2014. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(4):342–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper M, Pacek LR, Guy MC, et al. Hookah Use among U.S. Youth: A Systematic Review of the Literature from 2009–2017. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King JL, Reboussin D, Cornacchione Ross J, Wiseman KD, Wagoner KG, Sutfin EL. Polytobacco Use Among a Nationally Representative Sample of Adolescent and Young Adult E-Cigarette Users. J Adolesc Health. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell C, Rueda S, Room R, Tyndall M, Fischer B. Routes of administration for cannabis use - basic prevalence and related health outcomes: A scoping review and synthesis. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;52:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agrawal A, Budney AJ, Lynskey MT. The co-occurring use and misuse of cannabis and tobacco: a review. Addiction. 2012;107(7):1221–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cobb CO, Soule EK, Rudy AK, Sutter ME, Cohn AM. Patterns and Correlates of Tobacco and Cannabis co-use by Tobacco Product Type: Findings from the Virginia Youth Survey. Subst Use Misuse. 2018;53(14):2310–2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Apollonio DE, Spetz J, Schmidt L, Jacobs L, Kaur M, Ramo D. Prevalence and Correlates of Simultaneous and Separate 30-Day Use of Tobacco and Cannabis: Results from the California Adult Tobacco Survey. Subst Use Misuse. 2019:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trapl EK-G, S. J;. Adolescent Marijuana Use and Co-Occurrence with Tobacco Use: Implications for Tobacco Regulation. Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk. 2017;8(2). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Audrain-McGovern J, Stone MD, Barrington-Trimis J, Unger JB, Leventhal AM. Adolescent E-Cigarette, Hookah, and Conventional Cigarette Use and Subsequent Marijuana Use. Pediatrics. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schauer GL, Berg CJ, Kegler MC, Donovan DM, Windle M. Assessing the overlap between tobacco and marijuana: Trends in patterns of co-use of tobacco and marijuana in adults from 2003–2012. Addict Behav. 2015;49:26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG, et al. Association of Electronic Cigarette Use With Initiation of Combustible Tobacco Product Smoking in Early Adolescence. JAMA. 2015;314(7):700–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilliland FD, Islam T, Berhane K, et al. Regular smoking and asthma incidence in adolescents. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(10):1094–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roditis M, Delucchi K, Cash D, Halpern-Felsher B. Adolescents’ Perceptions of Health Risks, Social Risks, and Benefits Differ Across Tobacco Products. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(5):558–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glantz SA, Halpern-Felsher B, Springer ML. Marijuana, Secondhand Smoke, and Social Acceptability. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(1):13–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters EN, Bae D, Barrington-Trimis JL, Jarvis BP, Leventhal AM. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of adolescent use and polyuse of combustible, vaporized, and edible cannabis products. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(5):e182765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osibogun O, Taleb ZB, Bahelah R, Salloum RG, Maziak W. Correlates of poly-tobacco use among youth and young adults: Findings from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health study, 2013–2014. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;187:160–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General—Executive Summary. . In: Department of Health and Human Services CfDCaP, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, ed. Atlanta, GA: U.S: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knapp AA, Lee DC, Borodovsky JT, Auty SG, Gabrielli J, Budney AJ. Emerging Trends in Cannabis Administration Among Adolescent Cannabis Users. J Adolesc Health. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemyre A, Poliakova N, Belanger RE. The Relationship Between Tobacco and Cannabis Use: A Review. Subst Use Misuse. 2018:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berg CJ, Payne J, Henriksen L, et al. Reasons for Marijuana and Tobacco Co-use Among Young Adults: A Mixed Methods Scale Development Study. Subst Use Misuse. 2018;53(3):357–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hall W, Lynskey M. Evaluating the public health impacts of legalizing recreational cannabis use in the United States. Addiction. 2016;111(10):1764–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang JB, Ramo DE, Lisha NE, Cataldo JK. Medical marijuana legalization and cigarette and marijuana co-use in adolescents and adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;166:32–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orenstein DG, Glantz SA. Regulating Cannabis Manufacturing: Applying Public Health Best Practices from Tobacco Control. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2018;50(1):19–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.California Tobacco Education and Research Oversight Committee. New Challenges—New Promise for All: Master Plan 2018–2020. Sacramento, CA: California Tobacco Education and Research Oversight Committee;2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roditis ML, Delucchi K, Chang A, Halpern-Felsher B. Perceptions of social norms and exposure to pro-marijuana messages are associated with adolescent marijuana use. Prev Med. 2016;93:171–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berg CJ, Stratton E, Schauer GL, et al. Perceived harm, addictiveness, and social acceptability of tobacco products and marijuana among young adults: marijuana, hookah, and electronic cigarettes win. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(1):79–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.