Abstract

Background:

Microfinance interventions have the potential to improve HIV treatment outcomes, but the mechanisms through which they operate are not entirely clear.

Objectives:

To construct a synthesizing conceptual framework for the impact of microfinance interventions on HIV treatment outcomes using evidence from our systematic review.

Methods:

We conducted a systematic review by searching electronic databases and journals from 1996 to 2018 to assess the effects of microfinance interventions on HIV treatment outcomes, including adherence, retention, viral suppression, and CD4 cell count.

Results:

All studies in the review showed improved adherence, retention, and viral suppression, but varied in CD4 cell count following participation in microfinance interventions—overall supporting microfinance’s positive role in improving HIV treatment outcomes. Our synthesizing conceptual framework identifies potential mechanisms through which microfinance impacts HIV treatment outcomes through hypothesized intermediate outcomes.

Conclusion:

Greater emphasis should be placed on assessing the effect mechanisms and intermediate behaviors to generate a sound theoretical basis for microfinance interventions.

Keywords: microfinance, HIV treatment outcomes, adherence, conceptual framework, intermediate outcomes

RESUMEN

Antecedentes:

Las intervenciones de microfinanzas tienen el potencial de mejorar los resultados del tratamiento del VIH, pero los mecanismos a través de los cuales operan no están del todo claros.

Objetivos:

Construir un marco conceptual de síntesis del impacto de las intervenciones de microfinanzas en los resultados del tratamiento del VIH utilizando evidencia de una revisión sistemática.

Métodos:

Se llevó a cabo una revisión sistemática mediante búsquedas en bases de datos electrónicas y revistas desde 1996 hasta 2018 para evaluar los efectos de las intervenciones de microfinanzas en los resultados del tratamiento del VIH, incluida la adherencia, la retención, la supresión viral y el recuento de células CD4.

Resultados:

Todos los estudios en la revisión mostraron una mejor adherencia, retención y supresión viral, pero variaron en el recuento de células CD4 luego de la participación en las intervenciones de microfinanzas, lo que respalda el papel positivo de las microfinanzas en la mejora de los resultados del tratamiento del VIH. El marco conceptual de síntesis propuesto identifica los mecanismos potenciales a través de los cuales las microfinanzas impactan los resultados del tratamiento del VIH a través de resultados intermedios hipotéticos.

Conclusión:

Se debe poner mayor énfasis en evaluar los mecanismos de efecto y los comportamientos intermedios para generar una base teórica sólida para las intervenciones de microfinanzas.

BACKGROUND

Economic inequality plays a key role in the HIV epidemic (1). With respect to HIV treatment outcomes, people living with HIV from low-income households are more vulnerable to disease progression than those from higher income households (2). Through its ability to economically revitalize communities through group models and alleviate poverty—a key risk factor for HIV—microfinance interventions have been integral to HIV prevention (3), but less research has been conducted on the impact of microfinance interventions on HIV treatment outcomes for HIV-positive individuals (4). A recent comprehensive literature review on household economic strengthening in relation to retention in HIV care and adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) included the effect of income generation on HIV treatment outcomes (5). Our paper makes an additional contribution to the field by providing greater understanding of the hypothesized mechanisms behind the results.

This systematic review serves to: (a) assess the efficacy of microfinance interventions in improving HIV treatment outcomes, and (b) gather evidence to support the elements of a comprehensive, synthesizing conceptual framework. The studies cited in this review aim to assess how increased access to financial capital impacts individuals’ HIV treatment outcomes. We used the findings from our systematic review and previous literature reviews (5) on economic strengthening and HIV treatment to create a conceptual framework detailing the hypothesized behavioral, economic, and social pathways through which microfinance may influence HIV treatment outcomes. The treatment outcomes assessed in this review are adherence to ART, retention in HIV care, viral suppression and CD4 cell count.

METHODS

Definitions and inclusion criteria

We defined microfinance interventions as economic interventions that involved the disbursement of small loans and community savings to individuals in low- and middle-income countries. Adherence depicts the degree to which one’s behaviors correspond to the advice of health care providers (6). Retention, viral suppression (a measure of HIV-RNA), and CD4 cell count (a measure of the strength of the immune system) were also included as treatment outcomes.

Articles included in the systematic review were required to meet the following criteria:

Published in peer-reviewed journals.

Assessed microfinance interventions as described above.

Included HIV-positive individuals as the target population.

Evaluated quantitative impacts of microfinance interventions on HIV treatment outcomes.

Conducted in low- or middle-income countries.

Besides the aforementioned study criteria, no other restrictions were placed on study design, such that studies of various types and different levels of rigor that meet the study criteria were included in the systematic review.

Search strategy

Using the search terms defined below, we searched PubMed, PsycINFO, SocINDEX, CINAHL, EMBASE, and EconLit from January 1, 1996 to June 15, 2018. We also searched the table of contents of scientific journals related to HIV/AIDS according to the American Psychological Association (7): Health Psychology, AIDS & Behavior, AIDS Care, AIDS Education & Prevention, AIDS Prevention and Mental Health, American Journal of Public Health, Journal of AIDS/HIV, Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention & Education for Adolescents & Children, and AIDS.

Search terms

The following terms were used for all the electronic databases with slight modifications for particular formatting requirements: [(“microfinance” OR “micro-finance” OR “micro finance” OR “micro-credit” OR “microcredit” OR “micro credit” OR “income generation” OR “income generating” OR “economic empowerment” OR “cooperatives” OR “micro enterprise” OR “micro-enterprise” OR “microenterprise” OR “small loans” OR “micro loans” OR “microloans” OR “micro-loans”) AND (“treatment outcomes” OR “retention” OR “suppression” OR “CD4 cell counts” OR “viral load” OR “viral suppression” OR “adherence” OR “engagement”) AND (“HIV” OR “AIDS” OR “human immunodeficiency syndrome”)].

Screening abstracts

Full text articles, obtained using the above search strategy, were screened by three reviewers.

Data extraction and analysis

All articles in this review were reviewed by three reviewers. Discrepancies regarding which articles to include were resolved through discussion and consensus.

The following information was gathered from each study: location, target population, intervention description, study design, study size, duration, and outcomes. Study rigor was ranked using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project. We also checked if the studies explicitly used a conceptual framework. This information is presented in Tables I and II, respectively. Additional quality-related details are available in Table III.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Study Name and Country | Citation & reference number | Population Characteristics | Intervention Description | Study Design | Study Size | Study Duration | Outcomes: Intervention Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shamba Maisha, Kenya | Weiser et al., 2015 (12) | HIV-positive adults, aged 18–49 who were on antiretroviral therapy with access to surface water and land, signs of moderate to severe food insecurity or malnutrition present | 3-component intervention: 1) loan program, 2) MoneyMaker pump for irrigation, 3) agricultural and financial training. Participants in the control group continued ART but did not receive the intervention. | Pilot Clustered Randomized Control Trial. Biannual data was collected in health clinics to track treatment outcomes. | N=140 (Intervention group, n=72; control group, n=68) | 12 months | Intervention group: mean CD4 cell counts

increased by 75.6 cells/mm3 Control group: mean CD4 cell counts decreased by 89.3 cells/mm3 Difference between intervention and control at 12 months= 164.9 cells/mm3, p<0.001 Change in virologically suppressed among intervention group: 51% to 79%; control group: 72% to 67% Comparative improvement in proportion virologically suppressed=33% (95% CI= 2.2, 26.8; p=0.002) |

| Community-based Accompaniment with Supervised Antiretrovirals (CASA), Peru | Muñoz et al., 2010 (11) | HIV-positive individuals who recently started or were about to start ART. Priority in intervention groups given to the especially vulnerable, specifically women co-infected with tuberculosis. | Intervention group participants were enrolled in CASA, which included antiretroviral therapy (12 months of community-based DOT-ART), microfinance, and psychosocial support in accordance to individuals’ needs. | Matched Pairs Experiment. Each individual in the treatment group was compared to their assigned counterpart in the control group, in accordance with similar ailments and comorbidities. Clinical and psychosocial outcomes were recorded at 24 months. | N=120 (Intervention group, n=60; control group, n=60) | 24 months | After 2 years individuals in the CASA

intervention were more likely to remain on ART (86.7% v. 51.7%,

χ2=17.7, p<0.01), achieve

virologic suppression (66.7% v. 46.7%,

χ2=4.9, p=0.03), and report

adherence to treatment (79.3% v. 44.1%,

χ2= 15.3,

p<0.01) No significant differences in CD4 cell counts among groups |

| WFP Urban HIV/AIDS Nutrition and Food Security (UHANFS), Ethiopia | Bezabih, Weiser, Menbere, Negash, & Grede, 2018 (9) | HIV-positive individuals, who were or are currently on HIV treatment, at least 19 years old, food insecure at start of study, participated in economic strengthening (ES) activities for one or more years | Participants in the intervention group organized themselves into Village Saving and Loan Associations (VSLAs) and were given financial and management training. Those in the comparison group were also given the same economic intervention but did not have prior the one-year ES experience, as did those in the main intervention group. | Comparative Cross-Sectional Experiment. ES interventions were staggered over time, allowing for the finding of additional individuals for the comparison group who were selected from the same facilities as those in the main intervention. | N=1268 (Intervention group, n=643; comparison group, n=634) | Duration of intervention subject to individuals’ length of ES intervention; 5 year project | 9.9% of intervention group reported less than

95% treatment adherence vs. 25.9% of comparison group ES intervention increased chance of having 95% or greater ART adherence by factor of 2.416 (Visual Analog Scale; 95% CI: 1.699–3.435) and 5.610 (AIDS Control Trial Group; 95% CI: 2.559–12.301), compared to those not in ES, p<0.001 |

| Intervention Based on Microfinance, Entrepreneurship, and Adherence to Treatment (IMEA), Colombia | Arrivillaga et al., 2014 (8) | HIV-positive women, use of ART for the past 6 months, at least 18 years old, resident of Cali, Colombia, belonging to specific socioeconomic levels, literate | The intervention consisted of HIV/AIDS and treatment education (including self-care and family and social support), and treatment. Participants had the opportunity to learn about entrepreneurship and microenterprise through training and microfinance loans. | Pre-Post Study without Control Group. Scores of knowledge of HIV/AIDS, treatment, and adherence to treatment were measured; follow up actions were conducted 3 months after the conclusion of the intervention. | N=48 | 15 months | IMEA showed effectiveness in the majority of

score results, including those that tested knowledge of treatment and

adherence (p<0.001) The median score changes in adherence to treatment showed the greatest increase from 16.5 to 52.5 (p<0.001) |

| Enablers and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Cambodia, Cambodia | Daigle et al., 2015 (10) | HIV-positive, at least 19 years old, live in Battambang Province, must have been on ART for at least 1 year | MF intervention was applied to more than half (54.4%) of participants. | Observational Study. Retrospective data was collected in two main ways: 1) interviews and questionnaires and 2) via a clinical record review of participants’ ART visit history. | N=310 | 12 months | 20.4% of participants missed at least one of

five ART appointments Source of ART was associated with adherence (OR=0.68; 95% CI: 0.49–0.95; p=0.02) |

Table 2.

Quality Assessment of the Five Studies Included in Systematic Review

| Study Name and Country | Citation | Selection Bias | Study Design | Confounders | Blinding | Data Collection Method | Withdrawals and Dropouts | Overall Rating of the Papera | Includes Conceptual Framework |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shamba Maisha, Kenya | Weiser et al., 2015 (12) | 1 | 1 (Pilot Clustered Randomized Control Trial) | 1 | NA | 1 | 1 | Strong | No (referenced in a separate paper) |

| Community-based Accompaniment with Supervised Antiretrovirals (CASA), Peru | Muñoz et al., 2010 (11) | 1 | 2 (Matched Pairs Experiment) | 1 | NA | 1 | 1 | Strong | No |

| WFP Urban HIV/AIDS Nutrition and Food Security (UHANFS), Ethiopia | Bezabih, Weiser, Menbere, Negash, & Grede, 2018 (9) | 2 | 2 (Comparative Cross-Sectional Experiment) | 1 | NA | 1 | 1 | Moderate | No |

| Intervention Based on Microfinance, Entrepreneurship, and Adherence to Treatment (IMEA), Colombia | Arrivillaga et al., 2014 (8) | 2 | 2 (Pre-Post Study without Control Group) | 2 | NA | 1 | 1 | Moderate | No |

| Enablers and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Cambodia, Cambodia | Daigle et al., 2015 (10) | 3 | 3 (Observational Study) | 1 | NA | 1 | 1 | Weak | No |

Ratings were determined using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project. Assessment key: 1=Strong; 2= Moderate; 3= Weak; NA=Bias not applicable to study. Overall rating: Strong if four of the six ratings were strong with no weak rating; Moderate if less than four ratings are strong and one is weak; Weak if two or more ratings are weak.

Table 3.

Quality Assessment of the Five Studies Included in Systematic Review

| Study Name and Country | Citation | Cohort | Control or Comparison Group | Pre/Post Intervention Data | Random Assignment of Participants to the Intervention | Random Selection of Participants for Assessment | Follow Up Rate of 80% Or More | Comparison Groups Equivalent on Sociodemo-graphics at Baseline | Comparison Groups Equivalent at Baseline on Outcome Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shamba Maisha, Kenya | Weiser et al., 2015 (12) | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Community-based Accompaniment with Supervised Antiretrovirals (CASA), Peru | Muñoz et al., 2010 (11) | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| WFP Urban HIV/AIDS Nutrition and Food Security (UHANFS), Ethiopia | Bezabih, Weiser, Menbere, Negash, & Grede, 2018 (9) | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Intervention Based on Microfinance, Entrepreneurship, and Adherence to Treatment (IMEA), Colombia | Arrivillaga et al., 2014 (8) | Yes | No | Yes | NAa | No | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Enablers and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Cambodia, Cambodia | Daigle et al., 2015 (10) | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NRb |

NA=not applicable; b. NR=not reported

Due to the inconsistency of the studies in regard to interventions, target populations, design, and outcomes, meta-analysis of the data was not performed.

Using evidence from our systematic review, we have gathered the elements of a synthesizing conceptual framework to explain the potential psychological, social, and behavioral pathways that contributed to positive treatment-related behaviors and improved treatment outcomes. The potential pathways were determined through analysis of the similarities among various intermediate and treatment outcomes and noted behavioral observations across the articles in the review in conjunction with previous literature on conceptual frameworks in relation to HIV care.

RESULTS

Study descriptions

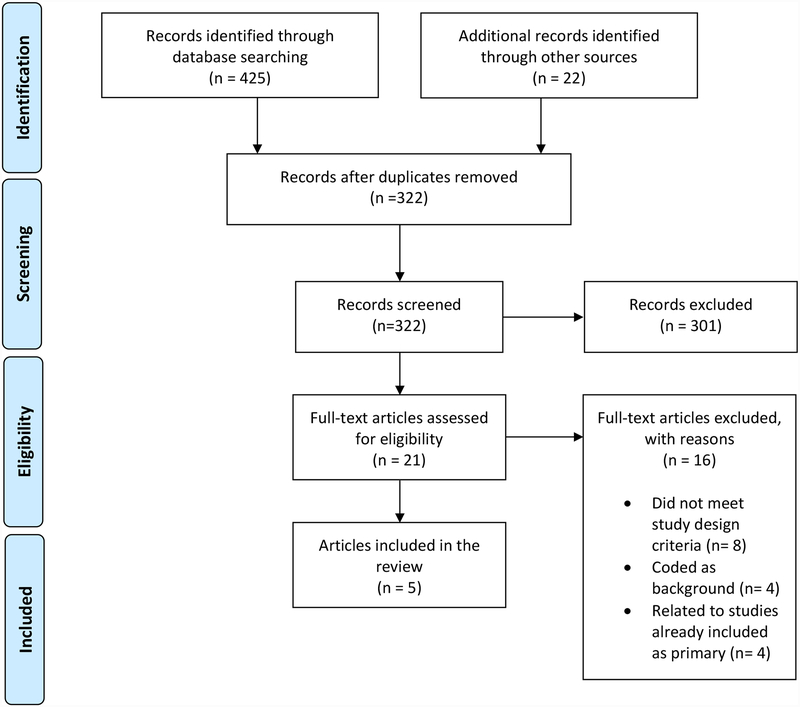

447 citations were identified, and of which 425 citations were found through electronic databases and 22 through secondary references and hand-searching the following journals: Health Psychology; AIDS & Behavior; AIDS Care; AIDS Education & Prevention; AIDS Prevention and Mental Health; American Journal of Public Health; Journal of AIDS/HIV; Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention & Education for Adolescents & Children; and AIDS (Figure 1). After the removal of duplicate studies, 322 citations were screened. Of these 322 citations, 21 were full-text articles and were accordingly assessed for eligibility and relevance. In order to be included in the systematic review, the full-text articles must have met the aforementioned study criteria, as described in the Definition and inclusion criteria section of the Methods. Of the 21 full-text articles reviewed, 16 were excluded on account of eight citations not meeting the study criteria, four pertaining only to background information, and four relating to other studies already included as primary in the review. Of the eight citations that did not meet the study criteria, five did not assess microfinance interventions, one described only qualitative results, and two did not include HIV-positive individuals as the target population. Finally, five interventions in five articles were included in the systematic review (8–12).

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Article Inclusion Process

The studies in this systematic review were geographically diverse, included only HIV-positive individuals who were on ART, and treated both adult male and female individuals, except one intervention that exclusively studied females (8).

Rankings were assigned to the studies using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project (Table II). Two of the studies were denoted as strong (11, 12), two as moderate (8, 9), and one as weak (10). Table III provides additional details on the quality and rigor of the studies.

Adherence and Retention

Four studies assessed adherence via self-reporting and interviews, and all showed improved adherence to ART with microfinance (8–11). The Enablers and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy study explicitly measured retention and found that 20.4% of participants missed at least one of five ART appointments, but appointment adherence was influenced by factors such as source of treatment, the presence of hospital-based support groups, and the frequency of adherence counselling (10).

Viral suppression

Two studies assessed viral suppression. The Shamba Maisha intervention performed HIV-RNA testing on venous blood to detect viral load with a lower limit detection of <40 copies/mL (12), and the CASA study defined virologic suppression as having a viral load of less than 400 copies per mL at 2 years (11). Both showed that involvement in microfinance interventions was associated with greater viral suppression (11, 12). The CASA study found this to be the case even when controlling for baseline differences like substance abuse (11).

CD4 cell counts

The results for CD4 cell counts were mixed. The Shamba Maisha intervention found that microfinance interventions resulted in a positive increase in CD4 cell counts in the intervention group, where the difference between the intervention and control at 12 months was 164.9 cells/mm3 (p<0.001) (12). The CASA study, which measured mean change in CD4 cell count compared to baseline at 24 months, however, did not find any significant differences in CD4 cell counts among individuals in the treatment and control groups (11).

Synthesizing Conceptual Framework

Using the findings from our systematic review, behavioral theory, and existing frameworks, specifically the Andersen-Newman Behavioral Model (13), we created a synthesizing conceptual framework for microfinance interventions and HIV. With the exception of the Shamba Maisha study, which included theoretical frameworks related to food insecurity and HIV treatment outcomes in a separate paper (14), none of the studies in this review included explicit conceptual frameworks as part of their intervention designs, warranting the need for this synthesizing conceptual framework.

Four of the interventions in our review explicitly incorporate education and training into the microfinance intervention, and all utilize a group model of microfinance (8, 9, 11, 12). As such, this model of microfinance—one that incorporates education and training in addition to the group component—is at the core of our conceptual framework. Working in conjunction with the expected additional income serviced through the microfinance loans, we hypothesize that these foundational elements potentially produced several intermediate outcomes that ultimately led to improved HIV treatment outcomes. Through an analysis of the studies in this systematic review, along with a search of the supporting literature, we hypothesize that these intermediate outcomes may include factors such as positive self-perception, reduced planning fallacy, greater propensity to save, social support and solidarity, improved mental well-being, and greater knowledge and skills. All of these outcomes are potential byproducts of microfinance interventions and can influence greater adherence and retention in regard to treatment, which was found in all of the studies included in this systematic review in response to microfinance interventions. In this way, these intermediate outcomes, deeply intertwined with community and social factors, serve as a stepping stone between the effects of microfinance interventions and the results of greater adherence and retention and ultimately improved biomarkers, such as CD4 cell count and viral suppression. Although the vulnerabilities of the population, which we specifically identified in terms of stigma, poverty, food insecurity, and gender inequality, influence both who is indicated for treatment as well as the efficacy of the interventions, these vulnerabilities can potentially be further reduced by the effects of the aforementioned intermediate outcomes in response to microfinance interventions.

In summary we propose through our conceptual framework that microfinance interventions are influenced by social and structural vulnerabilities (stigma, poverty, food insecurity, and gender inequality) and further influence the rise of potential intermediate outcomes (positive self-perception, reduced planning fallacy, greater propensity to save, social support and solidarity, improved mental well-being, and greater knowledge and skills), which can both reduce the burden of societal vulnerabitilies as well as produce improvements in measured HIV treatment outcomes, which is seen through higher adherence and retention and ultimately through the biomarkers of CD4 cell count and viral suppression.

It is important to note that all pathways and elements of this synthesizing conceptual framework are drawn from the analyis of the studies in this systematic review, along with supporting literature, but are ultimately hypothesized by the authors of this paper. Therefore, further research on these pathways and mechanisms is required to support their validity.

DISCUSSION

The extant results show that microfinance interventions are associated with improved adherence to ART, retention in HIV care, and viral suppression, but the mechanisms are unclear. Following a brief discussion on the contextualizing factors, we expand upon some of the summarized potential pathways and mechanisms through our synthesizing conceptual framework that may be operating to affect HIV treatment outcomes.

Contextual Factors

The distinct country-based levels of prevalence and access to treatment resources ultimately affect the degree of difficulty of obtaining treatment. Kenya, Ethiopia, and Cambodia, three of the five countries represented in our systematic review, are involved in The United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), a program that provides support for the provision of HIV prevention and antiretroviral therapy. Kenya and Ethiopia, whose adult HIV prevalence have recently been measured to be about 5.9% (15) and 0.9% (16) respectively, have mid-level prevalence, while Cambodia has a low HIV prevalence of 0.61% (17). Although Peru, with a low HIV prevalence of 0.4% (18), does not receive PEPFAR assistance, Peru’s universal healthcare system and the PAHO Drug Fund reduce the cost of treatment considerably (19). Colombia, however, with an adult HIV prevalence of 0.5% (20), is a not a PEPFAR country, nor does it have universal health care, making access to ART more challenging for PLWHIV. Further barriers, such as the lack of consistent transportation, opportunity costs, including job-related demands, and other hassle factors, contribute to the varying degrees of difficulty in accessing healthcare and HIV treatment specifically (21). These barriers can worsen the vulnerability of the population, potentially reducing the efficacy of microfinance interventions, thus complicating the pathways of our synthesizing conceptual framework.

The introduction of the consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection by the World Health Organization in 2016 further had a dramatic effect on access to ART, resulting in 45 low- and middle-income countries instituting the test and treat approach, which does not rely on a specific CD4 cell count for the provision of treatment (22). However, because only one of the studies included in the systematic review took place after 2016 (9), treatment for PLWHIV would have generally been less accessible during the time of the other studies (8, 10–12), compared to the present day, alluding to the greater role microfinance played in regard to ensuring more widespread HIV treatment.

Vulnerability of the Target Population

Stigma

While poverty, food insecurity, and gender inequality operate at the structural level, these vulnerabilities tend to impact treatment availability and health outcomes on an individual and familial basis, with community stigma operating as one of the driving forces that allows for the perpetuation of vulnerabilities. Existing at every stage of HIV progression, stigma exacerbates already-present vulnerabilities through the creation of social barriers that bring about behaviors that worsen the treatment outcomes of those affected, such as delayed testing or isolation due to shame or fear of social rejection (23). A systematic review of 75 studies found that stigma worsened ART adherence by undermining general psychological processes like adaptive coping and social support, which are integral aspects to retention and adherence (24). The constant burden of social stigma drove many PLWHIV to internalize the stigma and conceal their medical, social, and emotional needs, further worsening the improvement of intermediate and HIV treatment outcomes (24). Because stigma acts on a societal level, present even within microfinance interventions, dynamic social and upstream initiatives are needed to reduce stigma.

Poverty

Although great strides have been made in the affordability of antiretroviral therapy, especially through mechanisms such as PEPFAR and universal health care, costs—specifically transport costs—continue to restrict access to treatment (25). With their ability to foster entrepreneurial ambition, microfinance loans have the potential to strengthen economic conditions and access through income generation and skill development, as was seen in the UHANFS study where the prevalence of poverty decreased from 70% at baseline to 24.3% after 36 months with the economic intervention (9).

In regard to study design, it is crucial to note the degree of poverty faced by the target population, as providing loans to individuals who do not have the means or entrepreneurial acumen to repay poses significant ethical issues. The Shamba Maisha intervention screened participants’ ability to save an initial down payment of 500 Kenyan shillings (roughly 6 USD), before receiving the loan (about 150 USD) (12), allowing researchers to ensure that participants were financially able to participate in the intervention.

Another design concern is the tendency of participants in poverty to use microfinance funds for purposes other than business development. Because poor individuals are constantly faced with trade-offs and opportunity costs, many reroute the funds toward other areas of need, consistent with resource-constrained settings and the planning fallacy whereby people underestimate the resources needed to achieve specific tasks, including small enterprises (26). Funds in the CASA intervention were monitored to ensure that loans were only allocated towards business purchases (11). Multiple studies have cited the importance of providing auxiliary monthly support, food supplementation, and transportation to relieve some of the burdens of poverty and allow individuals to focus on using microfinance loans for income-generating activities (8, 11). This can produce powerful intermediate outcomes, such as reduced stress and changes in the opportunity costs of seeking treatment, allowing individuals to feel financially secure enough to access care, potentially improving adherence and retention and reducing vulnerability as income increases and viral load stabilizes. It is possible that income-generating activities also have positive psychological impacts on individuals, such as on self-perception, which can translate into positive behavioral changes and improved treatment outcomes. More research on the effects of microfinance interventions on intermediate outcomes, such as on psychological constructs like anxiety levels or propensity to save, is necessary to further support this mechanism.

This discussion of poverty as a significant vulnerability affecting participation in microfinance interventions raises many questions about the benefit of microfinance over other forms of social protection, such as unconditional and conditional cash transfers to reduce the burden of poverty, as opposed to providing loans that individuals must repay. It has been shown that cash transfers are relatively effective in reducing HIV infection and transmission (27) and can serve as life-saving aid for those who are too vulnerable or simply unable for a variety of reasons—such as a lack of entrepreneurial acumen, poor health, or other commitments—to participate in microfinance interventions. In establishing the study eligibility criteria, we decided to exclude studies from the systematic review that pertain to cash transfers without microfinance interventions. Partly due to the notion that cash transfers do not require payback mechanisms, they fail to provide some of the growth opportunities that are inherently part of microfinance interventions, such as communal accountability, entrepreneurial and financial skills, and ART treatment responsibility—skills that can potentially benefit individuals’ lives for years to come. Further, the Enablers and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Cambodia study that compared the effects of various forms of support in relation to ART adherence found that no significant associations were present between providing food and monetary support and ART adherence (10). Because of these differences, we felt that the variances between cash transfers and microfinance interventions were too vast to include both in our systematic review, but we continue to uphold the value of cash transfers and other forms of social protection that lack payback mechanisms, especially for those who are unable to participate in microfinance interventions; however, as previously mentioned, auxiliary support, a form of social support that might include food, money, or transportation, in tandem with microfinance interventions can often aid in the efficacy of the intervention by helping participants focus on building successful businesses for income-generating purposes and potentially subsequent improved health.

Food Security

Typically a byproduct of poverty, food insecurity can adversely affect HIV treatment outcomes through behavioral, nutritional, and mental health mechanisms through lowered healthcare utilization and decreased ART adherence (9). Anxiety from food insecurity can exacerbate mental health ailments, such as depression, worsening treatment outcomes (14). Since patients are typically instructed to take ART with food, medication is often skipped when food is scarce. The Shamba Maisha intervention directly addressed this issue by integrating a mechanism for greater food security into the economic intervention (12). By giving participants the agricultural resources to increase their food supply, along with the additional income generated through microfinance, the intervention fostered a positive feedback loop between improved HIV treatment outcomes and enhanced food security, as food consumption and BMI simultaneously increased with the increase of CD4 cell counts and viral suppression (14). Such an initiative also brought about significant mental and behavioral changes, specifically concerning perceptions about health status. Participants stated that their increased food intake made them feel healthier and more able to process the medicine, providing the motivation to be diligent with treatment regimens; some claimed that their weight gain boosted their social image, increasing their confidence and willingness to continue treatment (28). Similarly, the UHANFS intervention, whose participants were food insecure from the onset, saw indirect effects of microfinance on improved food security, implying a mutually beneficial, connected mechanism (9).

Another point of debate is the notion of providing food and nutritional assistance without a payback mechanism. Studies have shown that the provision of food and nutritional assistance can improve ART adherence, but determining how to allocate resources in the context of widespread need is challenging (9). Providing food assistance also poses significant long-term issues for sustainability and self-perception due to the potential stigma associated with receiving aid (12). Alternatively, microfinance interventions can provide the means for economic empowerment and a greater sense of purpose by potentially effecting long-term productivity, new skills, and a positive outlook on life (9). However, such forms of social protection that include food provisions without a payback mechanism might be crucial for those who are too vulnerable to participate in microfinance interventions, further supporting the need to effectively assess vulnerability of the target population and ability to participate fully before conducting microfinance interventions.

Gender

Women in most low- and middle-income settings are often especially vulnerable to HIV, due to constraints on individual opportunity, such as through limited education, and forms of structural marginalization, such as reduced autonomy and political influence (8). Having few income-generating opportunities further reduces access to healthcare and economic growth (29). The IMEA study attempted to address gender inequality by targeting microfinance interventions toward women (8). Although the CASA intervention was mixed gendered, it gave priority to women co-infected with HIV and latent tuberculosis (11). Because targeting the most vulnerable groups can pose ethical and efficacy concerns, given participants’ compromised state and subsequent difficulties in paying back loans, researchers attempted to offset this risk by removing individuals who were too vulnerable, specifically those who had active tuberculosis or mental afflictions that prevented them from participating in the group component of the intervention.

The two main approaches to addressing gender inequality in interventions are Women in Development (WID) and Gender and Development (GAD) (8). While both focus on empowering women, GAD relies more on the notion that women are their own agents for change, resulting in microfinance interventions that are potentially more sustainable because they seek to fundamentally shift women’s behaviors and perceptions of their place in society. This change in mindset, influenced by gender education as well as by the social support gained from being in a group setting, has the potential to make participants feel more deserving of treatment and better health, which can translate into behavioral changes like greater adherence or retention and subsequent improved HIV treatment outcomes (8). In addition to the empowerment of women, it has also been shown in other studies that microfinance interventions might reduce intimate partner violence overtime, improving women’s safety and self-worth, potentially increasing their adherence and retention for better treatment outcomes (30).

Reducing Vulnerability through Study Design

Analysis of the articles from this systematic review sheds light on the importance of various mechanisms in potentially inducing intermediate outcomes that can support behavioral changes for improved treatment outcomes, but these mechanisms are complicated by the vulnerabilities of the population. The planning fallacy—the notion that individuals are notoriously poor at predicting details about a task—exacerbates already-present vulnerabilities (31). Incorporating measures, such as early loan repayment deadlines, has the potential to alleviate this vulnerability and reduce the risk of default. Furthermore, implementing a trial period at the beginning of interventions to determine the most effective repayment intervals for participants can address the often-unpredictable income gains of individuals in poverty (26).

Another important consideration is the propensity of participants to borrow rather than save (26). Due to their increased vulnerability to unexpected shocks, such as unforeseen medical expenses, low-income communities are generally less able and prone to saving funds. The principle of immediate gratification supports the tendency to borrow as saving takes longer to reap its effects (26). These principles ultimately lead to over-borrowing and debt, justifying the need for financial management and savings education to be incorporated into microfinance interventions for sustained improvements. Such behaviors potentially increase the risk for poorer treatment outcomes, as they jeopardize the financial stability needed for treatment and retention. ROSCAS (Rotating Savings and Credit Associations), chit funds, and deposit collectors, who routinely collect individuals’ savings for later use, are important tools to instill the importance of savings measures by fundamentally changing individuals’ economic behaviors (32).

Education and Training

Although not part of the search criteria, four of the five studies in this systematic review incorporated education and/or training workshops in the economic interventions (8–10, 12), with the only exception being a retrospective study (11). The education and training workshops in these interventions pertained to financial management, agricultural production, entrepreneurial development, HIV, ART, and gender equity. The education and training components might have allowed for greater retention in the intervention, as participants felt more engaged and knowledgeable, fostering more successful income-generating activities, which can support motivation and intermediate behaviors that contribute to ART adherence and retention in the long run (8). Because these trainings significantly contribute to participants’ self-confidence and perceived ability to fulfill the intervention, Arrivillaga and colleagues argued that studies lacking such trainings ultimately carry less personal impact for the participants than those that include them (8). Similarly, within the context of HIV prevention, one study found that economic intervention alone is not sufficient to reduce the prevalence of HIV, but rather requires educational and social support to be effective (33). More research is warranted to determine how specific types of education and training that accompany microfinance interventions impact potential intermediate outcomes that might ultimately lead to improved HIV treatment outcomes.

The Group Effect

A stable group model for loan disbursement and savings is at the core of every intervention in this systematic review. While some research has highlighted the potential shift toward individual lending, group lending remains prevalent due to the wide array of potential financial and social benefits (34), often resulting in positive intermediate outcomes. This model is especially prevalent in low-income communities where individuals can pool their resources and rely on peers for support and accountability. Village Saving and Loan Associations (VSLA) are among the most effective group lending models for low-income communities, as they allow risk to be diversified and reduce risk for loan lenders (9, 35).

In addition to the microfinance portion of the intervention, the education and training components all took place in group settings, allowing participants to share their experiences and ideas, further fostering social support through shared goals. The social support provided through these groups is crucial to cultivating a sense of identity, motivation, and communal drive for success—all factors that may be crucial to changing behaviors like adherence, ultimately impacting HIV treatment outcomes (8). The group nature of these interventions provides potential pathways through which individuals can find solidarity and enforce positive self-perceptions (28).

Intermediate Outcomes

As an intermediate step toward producing improved HIV treatment outcomes, we hypothesize that microfinance interventions result in social and behavioral outcomes that essentially serve as the catalysts for potential behavioral changes—in terms of greater adherence and retention—that result in improved biomarker measures, like CD4 cell count and viral suppression. These potential intermediate outcomes include positive self-perception, reduced planning fallacy, greater propensity to save, social support and solidarity, improved mental well-being, and greater knowledge and skills.

One study conducted in rural Bangladesh aimed to measure women’s empowerment in relation to microfinance initiatives using regression models and characterized empowerment through the variables of mobility, economic security, ability to make small purchases, ability to make larger purchases, involvement in major decisions, and subjection to domination and violence, political/legal awareness, and participation in protests/campaigns, with these variable scores combined into a single score for analysis (30, 36). The regressions showed that the Grameen Bank, a form of microfinance, positively benefits women’s status and empowerment, especially by increasing women’s economic roles within their families. Further, contraceptive use was 11% higher in villages that utilized the Grameen Bank. Such factors are believed to give these microfinance participants a greater sense of agency, autonomy, and confidence in their ability to plan for the future (30, 36). We interpreted these results and assumptions as the intermediate outcomes of positive self-perception, reduced planning fallacy, and greater propensity to save—a testament to the increased financial knowledge and independence gained as a result of microfinance.

As previously mentioned in relation to the group effect through its tenets of community growth and interdependence, microfinance is generally believed to contribute to a greater sense of social solidarity—one of our hypothesized intermediate outcomes—as it inherently relies on providing loans to ‘solidarity groups’ that must work collectively to repay their debts (37). Furthermore, supporting literature has theorized that social solidarity has the power to mobilize communities and increase cohesiveness, which can potentially work to further improve the health of individuals through greater community support and encouragement (38).

In relation to the potential intermediate outcome of improved mental health, a study conducted in South India found that sustained membership in microfinance for more than two years was associated with less self-reported emotional stress when compared to those who did not participate in microfinance, indicating that microfinance might have potential positive effects on mental well-being, which can ultimately produce behavioral changes that support the decision to look after one’s health, potentially increasing adherence, retention, and subsequent HIV treatment outcomes (39). Although some studies have found mixed results in relation to microfinance and mental health, another study conducted in Bangladesh further supports the potential positive effect of microfinance on mental health, as those who participated in the microfinance intervention reported less social withdrawal during stressful events, signifying a greater ability to cope with difficulties and potentially improved mental well-being (40, 41).

Finally, as noted in the IMEA study in the systematic review that incorporated financial and health-related education in the microfinance intervention, the median scores of knowledge of HIV/AIDS and of treatment both increased significantly, highlighting the importance of well-rounded microfinance interventions in producing the intermediate outcome of greater knowledge and skills, which can further encourage behavioral changes that increase adherence and retention and eventual improved treatment outcomes as individuals have the knowledge base to make more informed decisions about their health and needs (8).

Limitations and Potential Consequences

Although we concluded that microfinance interventions generally support improved HIV treatment outcomes, the small number of studies, relatively small sample sizes in each, self-reported nature of specific outcomes, and the relatively atheoretical nature of the research field limit the strength of our conclusions. With the inclusion of education, training, and auxiliary support, none of the interventions tested the independent effects of microfinance alone on HIV treatment outcomes, but this is a testament to the need for holistic interventions for sustained effects.

Due to the scarce nature of the literature on the specific subject, it was necessary to include studies of diverse rigor in the systematic review, so long as they satisfied the aforementioned search criteria in the Methods section. The use of interview data in the observational study (10), which did not seem to be fully corroborated with clinical records, further weakened the overall rigor of the review through potential response bias (10). It should be noted that in many of the studies adherence was assessed by self-report, potentially inducing some inaccurate measures of adherence, most likely due to social desirability bias, in which participants tend to answer questions in a way that reflects more favorably upon them (8–11). Although adherence is most commonly measured using self-report due to the lower resources needed to collect this data, it often overestimates adherence, contributing to the ceiling effect, in which the data is inaccurately positively skewed due to this social desirability bias (42). Further research may be warranted in order to examine the impact of microfinance on HIV treatment outcomes using objective measures of adherence.

While there are numerous benefits of microfinance interventions, possible significant adverse consequences should also be considered. Monetary loans have the potential to increase pressure on individuals, exacerbated by the obligatory group nature of the intervention. In fishing communities near Lake Malawi, for example, some women who were given microfinance loans experienced a burden to repay the loans, worsened by the constraint that failure of one member to repay the loans would result in detriment for the whole group (4). These stressors caused some of the women in the intervention to perform sex work to repay the borrowed money, potentially putting the women at greater health risk than they were prior to the intervention.

CONCLUSION

Comprised of five studies, this systematic review assessed the influence of microfinance interventions on HIV treatment outcomes including adherence, retention, CD4 cell count and viral suppression. Microfinance interventions showed positive impacts in terms of improved adherence and viral suppression, but the results were mixed in regard to CD4 cell count. Through a synthesizing conceptual framework, we outlined the potential pathways and mechanisms that may contribute to effective ethical interventions. Further research, specifically focused on intermediate behavioral outcomes, is vital to supporting the validity of these mechanisms behind microfinance interventions in relation to HIV treatment outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper was partially funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants (R21-AI-118393; R34-MH-114664; K01MH099966; P2C-HD-041020). This work was facilitated by the Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research, CFAR (P30-AI-042853).

Acknowledgments:This work was facilitated by the Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research, CFAR (P30-AI-042853) and the Brown University Population Studies and Training Center, PSTC (P2C-HD-041020).

Funding: This paper was partially funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants (R21-AI-118393; R34-MH-114664; K01MH099966).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval: This review article does not contain any research with human participants or animals performed directly by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Gupta GR, Parkhurst JO, Ogden JA, Aggleton P, Mahal A. Structural approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet (London, England). 2008;372(9640):764–775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60887-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gitahi-Kamau NT, Kiarie JN, Mutai KK, Gatumia BW, Gatongi PM, Lakati A. Socio-economic determinants of disease progression among HIV infected adults in Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:733. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2084-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witte SS, Aira T, Tsai LC, et al. Efficacy of a Savings-Led Microfinance Intervention to Reduce Sexual Risk for HIV Among Women Engaged in Sex Work: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(3):e95–102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacPherson E, Desmond N, Mwapasa V, Lalloo DG, Seeley J, Theobald S. Exploring the complexity of microfinance and HIV in fishing communities on the shores of Lake Malawi. Malawi-Liverpool-Wellcome Trust Clin Res Program. 2015;30096(3). http://lshtmtest.da.ulcc.ac.uk/992527/1/MacPherson-finalversion.pdf. Accessed April 18, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swann M AIDS Care Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV Economic strengthening for retention in HIV care and adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a review of the evidence Economic strengthening for retention in HIV care and adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a review of the evidence. AIDS Care. 2018;30(S3):99–125. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1479030org/10.1080/09540121.2018.1479030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Defining Adherence.; 2003. http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_Section1.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2018.

- 7.Scientific Journals Related to HIV/AIDS. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/pi/aids/resources/research/journals.aspx. Published 2018. Accessed October 17, 2018.

- 8.Arrivillaga M, Salcedo JP, Pérez M. The IMEA Project: An Intervention Based on Microfinance, Entrepreneurship, and Adherence to Treatment for Women With HIV/AIDS Living in Poverty. AIDS Educ Prev. 2014;26(5):398–410. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2014.26.5.398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bezabih T, Weiser SD, Menbere MS, Negash A, Grede N. Comparison of treatment adherence outcome among PLHIV enrolled in economic strengthening program with community control. AIDS Care - Psychol Socio-Medical Asp AIDS/HIV. 2018. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1371667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daigle GT, Jolly PE, Chamot EAM, et al. System-level factors as predictors of adherence to clinical appointment schedules in antiretroviral therapy in Cambodia. AIDS Care. 2015. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1024098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muñoz M, Bayona J, Sanchez E, et al. Matching Social Support to Individual Needs: A Community- Based Intervention to Improve HIV Treatment Adherence in a Resource-Poor Setting. AIDS Behav. 2010;15:1454–1464. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9697-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiser SD, Bukusi EA, Steinfeld RL, et al. Shamba Maisha: randomized controlled trial of an agricultural and finance intervention to improve HIV health outcomes. AIDS. 2015;29(14):1889–1894. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrovic K, Blank TO. The Andersen-Newman Behavioral Model of Health Service Use as a conceptual basis for understanding patient behavior within the patient-physician dyad: The influence of trust on adherence to statins in older people living with HIV and cardiovascular disease. Cogent Psychol. 2015;2:1038894. doi: 10.1080/23311908.2015.1038894 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiser SD, Young SL, Cohen CR, et al. Conceptual framework for understanding the bidirectional links between food insecurity and HIV/AIDS. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(6):1729S–1739S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.012070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenya Country Operational Plan (COP) 2018 Strategic Direction Summary.; 2018. https://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/285861.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2019.

- 16.Ethiopia Country/Regional Operational Plan (COP/ROP) 2018 Strategic Direction Summary.; 2018. https://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/285863.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2019.

- 17.Strategic Direction Summary Cambodia Country Operational Plan. https://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/272005.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2018.

- 18.Vargas V The New HIV/AIDS Program in Peru: The Role of Prioritizing and Budgeting for Results.; 2015. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/21497/942600WP00PUBL0IV0AIDS0Program0Peru.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed September 4, 2018.

- 19.MLHW Country Case Studies. http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/MLHWCountryCaseStudies_annex12_Peru.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2018.

- 20.HIV and AIDS Estimates Country Factsheets Colombia 2017.; 2017.

- 21.BehavIoral EconomIcs and Social PolIcy Designing Innovative Solutions for Programs Supported by the Administration for Children and Families.; 2014. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre. Accessed September 4, 2018.

- 22.Prevent HIV, Test and Treat All: WHO Support for Country Impact Geneva; 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/251713/WHOHIV?sequence=1. Accessed January 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alonzo AA, Reynolds NR. Stigma, HIV and AIDS: An Exploration and Elaboration of a Stigma Trajectory. Vol 41; 1995. https://ac.els-cdn.com/0277953694003846/1-s2.0-0277953694003846-main.pdf?_tid=793d4d1d-1d00-434c-8365-d831014fe366&acdnat=1538531643_9d3961e1458c3d921f9deb6b784cd6c7. Accessed October 2, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013. doi: 10.7448/ias.16.3.18640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Govindasamy D, Ford N, Kranzer K. Risk factors, barriers and facilitators for linkage to antiretroviral therapy care. AIDS. 2012;26(16):2059–2067. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283578b9b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mullainathan S, Krishnan S. Psychology and Economics: What It Means for Microfinance.; 2008. www.financialaccess.orgwww.poverty-action.org. Accessed July 25, 2018.

- 27.Baird SJ, Garfein RS, Mcintosh CT, Özler B. Effect of a cash transfer programme for schooling on prevalence of HIV and herpes simplex type 2 in Malawi: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1320–1329. doi: 10.1016/S0140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiser SD, Hatcher AM, Hufstedler LL, et al. Changes in Health and Antiretroviral Adherence Among HIV-Infected Adults in Kenya: Qualitative Longitudinal Findings from a Livelihood Intervention. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(2):415–427. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1551-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gnauck K, Ruiz J, Kellett N, et al. Economic empowerment and AIDS-related stigma in rural Kenya: a double-edged sword? Cult Heal Sex An Int J Res Interv Care. 2013;15(7):851–865. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2013.789127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JC, Watts CH, Hargreaves JR, et al. Understanding the impact of a microfinance-based intervention on women’s empowerment and the reduction of intimate partner violence in South Africa. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(10):1794–1802. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.095521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertrand M, Mullainathan S, Shafir E. A Behavioral-Economics View of Poverty. Am Econ Assoc Pap Proc. 2004;94(2):419–423. https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/0002828041302019. Accessed July 25, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashraf N, Karlan D, Yin W. Tying Odysseus to the Mast:Evidence from a Commitment Savings Product in the Philippines. Q J Econ. 2006:635–672. https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/121/2/635/1884028. Accessed July 25, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dworkin SL, Blankenship K. Microfinance and HIV/AIDS Prevention: Assessing its Promise and Limitations. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:462–469. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9532-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kodongo O, Kendi LG. Individual lending versus group lending: An evaluation with Kenya’s microfinance data. Rev Dev Financ. 2013;3:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.rdf.2013.05.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmes K, Winskell K, Hennink M, Chidiac S. Microfinance and HIV mitigation among people living with HIV in the era of anti-retroviral therapy: Emerging lessons from Côte d’Ivoire. Glob Public Health. 2010. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2010.515235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hashemi SM, Schuler SR, Riley AP. Rural Credit Programs and Women’s Empowerment in Bangladesh. World Dev. 1996;24(4):635–653. https://ac.els-cdn.com/0305750X9500159A/1-s2.0-0305750X9500159A-main.pdf?_tid=89359ce6-5493-496f-a8c4-e3c7508fa49d&acdnat=1546644869_a387a74e95e4c53a6120687d911aad72. Accessed January 4, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morduch J The Microfinance Promise. J Econ Lit. 1999;37:1569–1614. https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jel.37.4.1569. Accessed January 4, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pronyk PM, Kim JC, Makhubele MB, et al. Microfinance and HIV prevention—emerging lessons from rural South Africa. Small Enterp Dev. 2005;16(3). https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7758/71dc32a008c6faea377f6b520c97f4b852d4.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohindra K, Haddad S, Narayana D. Can microcredit help improve the health of poor women? Some findings from a cross-sectional study in Kerala, India. Int J Equity Health. 2008;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-7-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmed SM, Chowdhury M. Micro-Credit and Emotional Well-Being: Experience of Poor Rural Women from Matlab, Bangladesh. World Dev. 2001;29(11):1957–1966. www.elsevier.com/locate/worlddev. Accessed January 4, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernald LC, Hamad R, Karlan D, Ozer EJ, Zinman J. Small individual loans and mental health: a randomized controlled trial among South African adults. 2008. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Berg KM, Arnsten JH. Practical and Conceptual Challenges in Measuring Antiretroviral Adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S79–87. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248337.97814.66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]