Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) survival has improved due to recent developments in MM treatment. As a result, other co-morbid conditions may be of increasing importance to MM patients’ long-term survival. This study examines trends in common causes of death among patients with MM in Puerto Rico, and in the US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) population.

We analyzed the primary cause of death among incident MM cases recorded in the Puerto Rico Central Cancer Registry (n=3,018) and the US SEER Program (n=67,733) between 1987–2013. We calculated the cumulative incidence of death due to the eight most common causes and analyzed temporal trends in mortality rates using joinpoint regression. Analyses of SEER were also stratified by Hispanic ethnicity.

MM accounted for approximately 72% of all reported deaths among persons diagnosed with MM in Puerto Rico and in SEER. In both populations, the proportion of patients who died from MM decreased with increasing time since diagnosis. Age-standardized temporal trends showed a decreased MM-specific mortality rate among US SEER (annual percent change [APC]= −5.0) and Puerto Rican (APC=−1.8) patients during the study period, and particularly after 2003 in non-Hispanic SEER patients. Temporal decline in non-MM causes of death was also observed among US SEER (APC=−2.1) and Puerto Rican (APC=−0.1) populations.

MM-specific mortality decreased, yet remained the predominant cause of death for individuals diagnosed with MM over a 26-year period. The most pronounced decreases in MM-specific death occurred after 2003, which suggests a possible influence of more recently developed MM therapies.

Keywords: Multiple myeloma, temporal trends, cause of death, Puerto Rico

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a cancer of plasma cells in the bone marrow which is characterized by the production of large amounts of abnormal monoclonal protein, or “M protein”.1 MM accounts for 1% of all cancers and approximately 10% of all hematologic malignancies diagnosed in the US each year.2 In 2018, 30,770 new cases and 12,770 deaths from MM were expected in the US, with only 50.7% of MM patients surviving 5 years after diagnosis.3 Few risk factors for MM are known, but men are slightly more likely to develop MM than women, and African Americans are twice as likely to develop MM as white Americans.4 Other risk factors for MM include a history of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), family history of MM or related conditions, and obesity.5,6

The development of new treatments for MM over the past 10–15 years has encouragingly extended the median survival of patients with this condition. Patients diagnosed with this malignancy in the US had a 5-year survival rate of only 25–30% in the late 1970s,7 whereas expected survival has doubled to 50.7% approximately 40 years later.4 Considering that patients are generally diagnosed with MM at older ages — e.g., on average at age 70, when other co-morbidities are also more common8 — and that survival rates for MM patients have improved, 4 it is likely that causes of death other than MM will be increasingly more common among MM patients in the coming years.

The Commonwealth of Puerto Rico is an unincorporated territory of the US with a population of approximately 3.6 million, primarily of Hispanic origin (98%).9 It has been shown that cancer trends in Puerto Rico differ strikingly from those of the continental United States.10 Puerto Ricans also exhibited higher cancer mortality rates than other Hispanic ethnic groups in a recent study.11 To the best of our knowledge, MM mortality has not been specifically investigated in the Puerto Rican population. In addition, changing trends in the cause of death in persons diagnosed with MM has not yet been examined in the US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) and Puerto Rican populations. We hypothesized that, although MM still accounts for most deaths among patients with this disease, a higher percentage of people may be dying from other causes in recent years when compared to earlier periods. In addition, due to varying prevalence of lifestyle risk factors and healthcare access,12 it is possible that the specific causes of death may be different for patients diagnosed with MM in Puerto Rico compared to Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients included in the US SEER population.

Materials and Methods

Study population and data sources

This study involved a secondary analysis of the databases of the Puerto Rico Central Cancer Registry (PRCCR) and the SEER Program of the National Cancer Institute. The PRCCR is responsible for collecting, analyzing, and publishing information on all cases of cancer diagnosed and/or treated in Puerto Rico since 1950. The PRCCR has been part of the CDC’s National Program of Cancer Registries since 1997 and has complete information available from 1987 (http://www.rcpr.org/).13 The SEER program has collected data on cancer incidence and mortality from various locations throughout the US since 1973 (https://seer.cancer.gov/). The present analysis includes data from the SEER 18 registries.14 PRCCR uses similar standards for coding data to those used by SEER, making the resulting data comparable.

This analysis included all MM cases aged 40 and older reported to the PRCCR and the SEER Program and diagnosed between 1987–2013, because less than 1% of MM cases are diagnosed under age 40. We began the study period in 1987 since this was the first year when complete data were available from both study populations. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Massachusetts Medical School, and a written letter of approval for this analysis was obtained from the PRCCR.

Case ascertainment

A total of 4,246 cases of MM were diagnosed in Puerto Rico between 1987 and 2013. We excluded cases with unknown diagnostic confirmation (n=624), different histologic type (other than ICD-O-3 morphology code 9732; n=308), cases with a secondary diagnosis of MM (n=233), and those who were missing age at diagnosis (n=11), leaving 3,018 cases from the PRCCR in the analysis.

The US SEER Program data were extracted using SEER*Stat’s client-server mode.15 A total of 91,894 cases of MM were diagnosed in the US SEER population from 1987 to 2013. We excluded cases of unknown diagnostic confirmation (n=4,056), cases with a different histologic type (other than ICD-O-3 morphology code 9732; n= 5,700), cases with a secondary diagnosis of MM (n=13,387), and people <40 years old (n=1,018), leaving 67,733 MM cases from SEER in the analysis (61,138 non-Hispanic and 6,595 Hispanic).

Cause of death data

For patients with MM diagnosed in Puerto Rico, de-identified cause of death data were provided by the Demographic Registry of Puerto Rico at the Puerto Rico Department of Health. The Registry used the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) to code deaths occurring from 1987 to 1998 and the ICD Tenth Edition (ICD-10) to code deaths occurring between 1999 and 2013. The SEER program used the ICD-9 to classify cause of death for people who died from 1979 through 1998 and the ICD-10 to code deaths that occurred thereafter.

The causes of death of study participants were harmonized between the US SEER and Puerto Rico registries. We focused on MM and on the eight most common categories of non-MM cause of death: certain infectious and parasitic diseases; diseases of the circulatory system; diseases of the genitourinary system; diseases of the nervous system; diseases of the respiratory system; endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases; other cancers; and all other causes of death. Cause of death categories were defined by ICD codes in the PRCCR (Supplemental Table 1) and by predetermined, descriptive categories based on ICD codes in the US SEER population (Supplemental Table 2), as individual ICD codes were not available for the SEER population.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics were compared between persons diagnosed with multiple myeloma by population (Puerto Rico, Hispanic-SEER, Non-Hispanic-SEER). Chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables between populations. We described the distribution of the most common causes of death among patients with MM in Puerto Rico, and the overall SEER population, and further examined cause of death stratifying the SEER population by Hispanic ethnicity. Cause of death was examined overall and by gender, age at MM diagnosis, calendar year of MM diagnosis, and survival time. Survival time was calculated from the date of MM diagnosis to the recorded date of death, loss to follow-up, or the end of follow-up (December 31, 2013), whichever occurred first. We assessed the distribution of causes of death among patients diagnosed with MM by calculating the percentage of total deaths and the cumulative incidence of death from each of the selected causes using total deaths among patients with MM as the denominator. We also examined temporal changes in cause of death by calendar period defined by developments of new therapies for this disease.7 All analyses of the SEER population were also stratified by Hispanic ethnicity (Hispanic versus non-Hispanic).

We calculated annual age-Standardized mortality rates using the 2000 US Standard Population (10 age groups - Census P25–1130). We then used joinpoint regression to identify the best-fit line through 26 years of annual age-standardized mortality rates, looking separately at death from MM and from other causes. The annual percent change (APC) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated using the Joinpoint Regression Program (Version 4.6.0.0) available from the National Cancer Institute.16 The Joinpoint Regression Program identifies the number of significant joinpoints by performing several permutation tests.17 For comparison to the joinpoint regression findings, we calculated one-year limited duration prevalence estimates. For the purposes of the prevalence estimates, the population at risk in 1987 was defined as all men and women diagnosed with MM in 1987. In 1988 and subsequent years, we defined the population at risk as people diagnosed with MM from all previous years. The age-standardized joinpoint regression results were similar to those based on the limited-duration prevalence estimates, and thus only the results of the joinpoint regression are presented. All other analyses were conducted in STATA 13.18

Results

MM was diagnosed slightly more often in men than women in both populations. The median age at diagnosis was the same among non-Hispanics in the SEER population and in Puerto Rico at approximately 69 years old, but slightly lower among Hispanics in SEER at 65 years (p-value <0.01) (Table 1). The median survival time was longer for cases diagnosed in the US SEER population than in Puerto Rico (two years vs one year, respectively; p<0.01), and the median age at death was 2 years older in the US SEER population. In both populations, patients with MM were more likely to die from MM than from other causes during the study period. Among all deaths occurring in the study period, approximately 72.0% were due to MM in both populations. The second most common cause of death in MM patients in Puerto Rico was from other cancers (11.2%) followed by diseases of the circulatory (5.3%) and respiratory (3.7%) systems. In the US SEER population, the second most common cause of death was diseases of the circulatory system (11.6% of non-Hispanics and 10.0% of Hispanics) followed by other causes of death (5.7% non-Hispanics and 4.6% Hispanics) and other cancers (5.3% non-Hispanics and 4.6% Hispanics).

Table 1.

Population characteristics of persons diagnosed with multiple myeloma in the Puerto Rico Central Cancer Registry and the United States Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) 1987–2013

| Characteristics | Overall US SEER | Non-Hispanics US SEER |

Hispanics US SEER | Puerto Rico4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=67,733) | (n=61,138) | (n=6,595) | (n=3,018) | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Male | 36,177 | 53.4 | 32,691 | 53.5 | 3,486 | 52.9 | 1,537 | 50.9 |

| Median age at diagnosis, years | 69 | 69 | 65 | 69 | ||||

| Age at diagnosis in years | ||||||||

| 40-59 | 17,410 | 25.7 | 15,190 | 24.9 | 2,220 | 33.7 | 686 | 22.7 |

| 60-69 | 18,401 | 27.2 | 16,503 | 27.0 | 1,898 | 28.8 | 889 | 29.5 |

| 70-79 | 19,460 | 28.7 | 17,812 | 29.1 | 1,648 | 25.0 | 947 | 31.4 |

| ≥80 | 12,462 | 18.4 | 11,633 | 19.0 | 829 | 12.6 | 496 | 16.4 |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||||

| 1987–1997 | 13,226 | 19.5 | 12,375 | 20.2 | 851 | 12.9 | 999 | 33.1 |

| 1998-2002 | 12,670 | 18.7 | 11,500 | 18.8 | 1,170 | 17.7 | 388 | 12.8 |

| 2003-2007 | 17,227 | 25.4 | 15,446 | 25.3 | 1,781 | 27.0 | 577 | 19.1 |

| 2008-2013 | 24,610 | 36.3 | 21,817 | 35.7 | 2,793 | 42.4 | 1,054 | 34.9 |

| Median survival time, years | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Median age at death, years | 74 | 74 | 71 | 72 | ||||

| Died from all causes | 46,746 | 69 | 42,648 | 69.8 | 4,098 | 62.1 | 2,293 | 76 |

| Died from multiple myeloma | 33,336 | 49.2 | 30,280 | 49.5 | 3,056 | 46.3 | 1,628 | 54 |

| Died from other cause | 13,410 | 19.8 | 12,368 | 20.2 | 1,042 | 15.8 | 665 | 22 |

| Censored1 | 20,987 | 31 | 18,490 | 30.2 | 2,497 | 37.9 | 725 | 24 |

| Cause-specific death | ||||||||

| Myeloma | 33,336 | 71.3 | 30,280 | 71 | 3,056 | 74.6 | 1,628 | 71.7 |

| Certain infectious and parasitic diseases | 644 | 1.4 | 596 | 1.4 | 48 | 1.2 | 34 | 1.5 |

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 5,360 | 11.5 | 4,948 | 11.6 | 412 | 10.0 | 121 | 5.3 |

| Diseases of the genitourinary system | 692 | 1.5 | 642 | 1.5 | 50 | 1.2 | 42 | 1.8 |

| Diseases of the nervous system | 141 | 0.3 | 134 | 0.3 | 7 | 0.2 | 13 | 0.6 |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 1,142 | 2.4 | 1,057 | 2.5 | 85 | 2.1 | 85 | 3.7 |

| Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases | 382 | 0.8 | 320 | 0.7 | 62 | 1.5 | 40 | 1.8 |

| Other cancer2 | 2,443 | 5.2 | 2,255 | 5.3 | 188 | 4.6 | 254 | 11.2 |

| Other causes of death3 | 2,606 | 5.6 | 2,416 | 5.7 | 190 | 4.6 | 54 | 2.4 |

SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Alive as of December 2013 or lost to follow-up.

US SEER included malignant neoplasms, stated or presumed to be primary, of lymphoid, hematopoietic and related tissue (n=611, 25%) and malignant neoplasms of independent (primary) multiple sites (n=448, 18%); Puerto Rico include malignant neoplasm of ill-defined, secondary and unspecified sites (n=61, 24%) and malignant neoplasms, stated or presumed to be primary, of lymphoid, hematopoietic and related tissue (n=60, 23%).

US SEER included unspecified other causes of death (n=1,953, 74%) and accidents/adverse events (n=298, 11.4%); Puerto Rico include diseases of digestive system (n=19, 35%) and symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified (n=18, 33%), and accidents/adverse events (n=12, 22%).

All p-values for the comparisons between non-Hispanic SEER, Hispanic SEER and Puerto Rico populations were <0.02

A greater proportion of deaths from MM occurred in men (51.9% in Puerto Rico; and 52.5% of non-Hispanics and 51.4% of Hispanics in SEER) than in women (48.1% in Puerto Rico; and 47.5% of non-Hispanics and 48.6% of Hispanics in SEER) in both populations during the study period (Table 2). The mean age at death from both MM and other causes was higher among non-Hispanics in SEER when compared to both Puerto Ricans and Hispanics in SEER (p-value< 0.001). Furthermore, Hispanics in SEER had a younger median age at death from both MM and other causes than Puerto Ricans.

Table 2.

Distribution of causes of death for people diagnosed with multiple myeloma in the Puerto Rico Central Cancer Registry, 1987–2013 and the United States Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER), 1987–2013

| Population characteristics | Overall US SEER | Non-Hispanics-SEER | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Died from multiple myeloma |

Died from other cause2 |

Censored1 | Died from multiple myeloma |

Died from other cause2 |

Censored1 | |

| All patients, N | 33,336 | 13,410 | 20,987 | 30,280 | 12,368 | 18,490 |

| Gender, N (%) | ||||||

| Male | 17,468 (52.4) | 7,426 (55.4) | 11,283 (53.8) | 15,897(52.5) | 6,845 (55.3) | 9,949 (53.8) |

| Female | 15,868 (47.6) | 5,984 (44.6) | 9,704 (46.2) | 14,383 (47.5) | 5,523 (44.7) | 8,541 (46.2) |

| Median age at diagnosis, years | 70 | 73 | 63 | 70 | 73 | 63 |

| Age at diagnosis in years, N (%) | ||||||

| 40-59 | 7,335 (22.0) | 2,101 (15.7) | 7,974 (38.0) | 6,447 (21.3) | 1,877 (15.2) | 6,866 (37.1) |

| 60-69 | 8,691 (26.1) | 3,014 (22.5) | 6,696 (31.9) | 7,807 (25.8) | 2,745 (22.2) | 5,951 (32.2) |

| 70-79 | 10,370 (31.1) | 4,561 (34.0) | 4,529 (21.6) | 9,553 (31.5) | 4,219 (34.1) | 4,040 (21.8) |

| ≥80 | 6,940 (20.8) | 3,734 (27.8) | 1,788 (8.5) | 6,473 (21.4) | 3,527 (28.5) | 1,633 (8.8) |

| Year of diagnosis, N (%) | ||||||

| 1987-1997 | 9,212 (27.6) | 3,550 (26.5) | 464 (2.2) | 8,608 (28.4) | 3,364 (27.2) | 403 (2.2) |

| 1998-2002 | 8,150 (24.4) | 3,204 (23.9) | 1,316 (6.3) | 7,424 (24.5) | 2,945 (23.8) | 1,131 (6.1) |

| 2003-2007 | 9,318 (27.9) | 3,769 (28.1) | 4,140 (19.7) | 8,347 (27.6) | 3,437 (27.8) | 3,662 (19.8) |

| 2008-2013 | 6,656 (20.0) | 2,887 (21.5) | 15,067 (71.8) | 5,901 (19.5) | 2,622 (21.2) | 13,294 (71.9) |

| Median age at death, years | 73 | 76 | _ | 73 | 76 | _ |

| Population characteristics | Hispanic SEER | Puerto Rico | ||||

|

Died from multiple myeloma |

Died from other cause2 |

Censored1 |

Died from multiple myeloma |

Died from other cause2 |

Censored1 | |

| All patients, N | 3,056 | 1,042 | 2,497 | 1,628 | 665 | 725 |

| Gender, N (%) | ||||||

| Male | 1,571 (51.4) | 581 (55.8) | 1,334 (53.4) | 845 (51.9) | 359 (54.0) | 333 (45.9) |

| Female | 1,485 (48.6) | 461 (44.2) | 1,163 (46.6) | 783 (48.1) | 306 (46.0) | 392 (54.1) |

| Median age at diagnosis, years | 67 | 70 | 61 | 69 | 71 | 66 |

| Age at diagnosis in years, N (%) | ||||||

| 40-59 | 888 (29.1) | 224 (21.5) | 1,108 (44.4) | 353 (21.7) | 108 (16.2) | 225 (31.0) |

| 60-69 | 884 (28.9) | 269 (25.8) | 745 (29.8) | 481 (29.6) | 190 (28.6) | 218 (30.1) |

| 70-79 | 817 (26.7) | 342 (32.8) | 489 (19.6) | 508 (31.2) | 239 (35.9) | 200 (27.6) |

| ≥80 | 467 (15.3) | 207 (19.9) | 155 (6.2) | 286 (17.6) | 128 (19.3) | 82 (11.3) |

| Year of diagnosis, N (%) | ||||||

| 1987-1997 | 604 (19.8) | 186 (17.8) | 61 (2.4) | 671 (41.2) | 251 (37.7) | 77 (10.6) |

| 1998-2002 | 726 (23.8) | 259 (24.9) | 185 (7.4) | 235 (14.4) | 101 (15.2) | 52 (7.2) |

| 2003-2007 | 971 (31.8) | 332 (31.9) | 478 (19.1) | 322 (19.8) | 148 (22.3) | 107 (14.8) |

| 2008-2013 | 755 (24.7) | 265 (25.4) | 1,773 (71.0) | 400 (24.6) | 165 (24.8) | 489 (67.4) |

| Median age at death, years | 69 | 73 | _ | 71 | 74 | _ |

= not applicable.

Alive as of December 2013 or lost to follow-up.

Other causes of death include certain infectious and parasitic diseases; circulatory system; genitourinary system; nervous system; respiratory system; endocrine, nutritional and metabolic; other cancers; other causes of death.

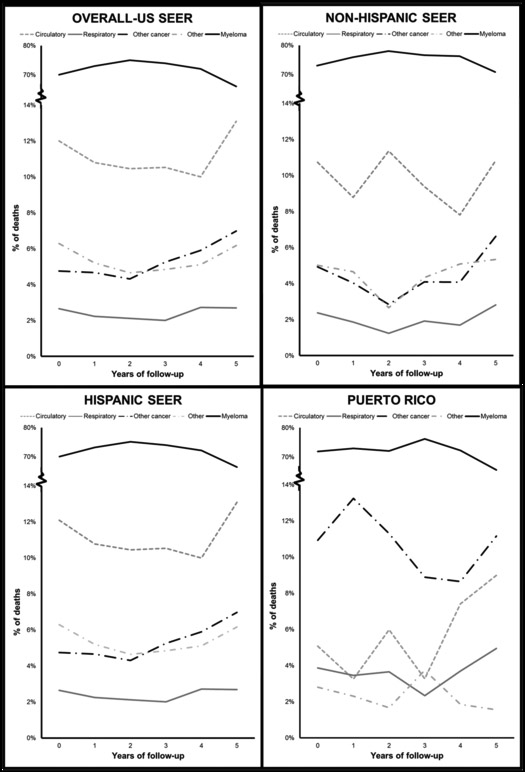

In general, MM patients were more likely to die from MM than from other causes across all time periods in all populations (Figure 1); nonetheless, the proportion of deaths due to MM decreased somewhat for patients who lived three or more years after diagnosis in Puerto Rico and those living two or more years after diagnosis in the SEER population (in both non-Hispanics and Hispanics). The decrease in the proportion of MM-specific deaths coincided with a slight increase in the proportion of deaths from causes other than MM for patients who lived longer. In these patients, we observed increasing proportions of deaths due to other cancers and diseases of the circulatory and respiratory systems in Puerto Rican patients, and due to circulatory system diseases, other cancers and other causes of death in SEER patients.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the most common causes of death in multiple myeloma patients diagnosed from 1987 to 2013 in Puerto Rico and the United States SEER population (non‐Hispanic and Hispanic), by population and years since diagnosis.

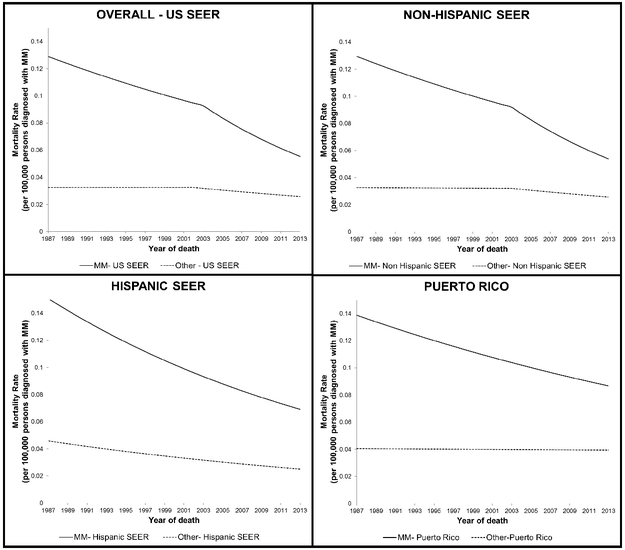

The results of the joinpoint regression suggest that while MM-specific mortality declined in all populations over the study period, trends in non-MM causes varied by population. In the non-Hispanic SEER population between 1987 and 2003, we observed an annual percent decrease of 2.1% per year in deaths from MM, which grew to an annual percent decrease of 5.2% per year from 2003 to 2013 in age-standardized temporal trends models (Figure 2 and Table 3). In the Hispanic SEER population between 1987 and 2013, we observed an annual percent decrease of 3.0%, with no distinction over the time period. In Puerto Rico, an annual percent decrease of only 1.8% per year was observed between 1987 and 2013 (Table 3). We observed fairly steady mortality rates from all non-MM causes in the SEER population through 2003. From the joinpoint regression, we also observed an annual percent decrease of 2.0% per year in death from all non-MM causes from 2003 to 2013 among non-Hispanics, while the Hispanic US SEER population had an annual percent decrease in non-MM causes of 2.3% from 1987 to 2013. In contrast, in Puerto Rico, an annual decrease in non-MM death of just 0.1% per year was observed (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Age‐standardized annual rates of death from multiple myeloma and other causes by year of death in the Puerto Rican and United States SEER populations, 1987–2013, estimated by joinpoint regression. *Rates are age‐standardized to the 2000 US Standard Population (10 age groups ‐ Census P25‐1130). The category for other causes of death includes certain infectious and parasitic diseases; circulatory system; genitourinary system; nervous system; respiratory system; endocrine, nutritional and metabolic; other cancers; other causes of death.

Table 3.

The estimated annual percentage change (APC) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of mortality rates from multiple myeloma and other causes of death by calendar period using joinpoint regression, and age-standardized to the United States population in 2000.

| Death from multiple myeloma | Other cause of death1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Calendar period | APC (95% CI) | n | Calendar period | APC (95% CI) | |

| Overall US SEER2 | 33,336 | 1987-2003 | −2.0 (−2.8, −5.2) | 13,410 | 1987-2002 | 0.1 (−1.1, 1.2) |

| 2003-2013 | −5.0 (−5.8, −4.3) | 2002-2013 | −2.1 (−2.8, −1.4) | |||

| Non-Hispanics SEER | 30,280 | 1987-2003 | −2.1 (−2.9, −1.3) | 12,368 | 1987-2003 | −0.1 (−1.2,1) |

| 2003-2013 | −5.2 (−6, −4.4) | 2003-2013 | −2.2 (−3.2, −1.3) | |||

| Hispanics SEER | 3,056 | 1987-2013 | −3.0 (−3.7, −2.2) | 1,042 | 1987-2013 | −2.3 (−3.9, −0.7) |

| Puerto Rico | 1,628 | 1987-2013 | −1.8 (−3.1, −0.5) | 665 | 1987-2013 | −0.1 (−1.8, 1.6) |

The non-MM category includes all causes of deaths (certain infectious and parasitic diseases; circulatory system; genitourinary system; nervous system; respiratory system; endocrine, nutritional and metabolic; other cancers; other causes of death).

Overall US SEER population includes both non-Hispanics and Hispanics.

Discussion

We examined temporal trends in causes of death among patients with MM over 26 years in two well-defined populations. Despite recent improvements in the treatment and long-term survival of patients with MM, people diagnosed with MM in Puerto Rico and the US SEER population, including Hispanics and non-Hispanics, remain more likely to die from MM. However, in the most recent years, a decrease in the overall number of deaths from MM was evident. We observed a slight increase in the proportion of deaths resulting from non-MM causes with increasing survival time since diagnosis, which may be due to more effective treatments prolonging the lives of MM patients.19 We also observed a decrease in both MM and non-MM causes of death, particularly among non-Hispanics in the SEER population since 2003; this could reflect patients living longer after their MM diagnosis, or a decrease in overall mortality in the SEER population, as a decline in the age-standardized death rate in the United States has been reported.20 However, it should also be noted that the Hispanic SEER population and the Puerto Rican population were much smaller, and may have lacked the statistical power to detect such a trend.

The results of the joinpoint regression analysis suggested that, in Puerto Rico overall, deaths from MM have decreased over the study period, while deaths from other causes have also decreased slightly as patients survive longer past diagnosis. Similarly, in the SEER population, we observed a decrease in the proportion of deaths from both MM and other causes over the study period, although the decrease in deaths from MM was greater in magnitude than the decrease in deaths from non-MM causes. The more striking decline in both MM and other causes of death among the SEER population could be explained in part by improvements in MM treatment options.21 However, this may differ in Puerto Rico where the decrease in the proportion of deaths was lower than in the SEER population. Puerto Ricans are known to be vulnerable to cancer disparities and may have less access to new treatments due to higher cost,22 potentially due to socioeconomic inequalities. Approximately 44% of the population of Puerto Rico lives in poverty,23 although the percentage of individuals in Puerto Rico without health insurance was lower (6%) compared with mainland US (9%) in a 2015 survey.24

We also observed different distributions of non-MM causes of death between populations. In Puerto Rico, other cancers, diseases of the circulatory system, and diseases of the respiratory system were the three most common non-MM causes of death among MM patients, while in the SEER population including both non-Hispanics and Hispanics, diseases of the circulatory system, other causes of deaths, and other cancers were the most common. Cause of death among Hispanics in the SEER population appeared more similar to non-Hispanics in SEER than to MM patients in Puerto Rico. Due to existing evidence for an increased risk of certain types of secondary cancers like bone and other lymphoid cancers in survivors of MM, it is not surprising that other cancers would comprise one of the major non-MM causes of death in MM patients; however we were unable to assess the contribution of specific cancer types.25,26 Circulatory disease, which includes ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease, was among the top non-MM causes of death in both populations. It is known that MM pathogenesis and treatment may increase the risk of cardiovascular events; pre-existing cardiovascular risk factors could increase an MM patient’s risk of dying from this secondary cause.27 In addition, respiratory disease was a common cause of death in Puerto Rico, but not among the top causes in the SEER population. The respiratory tract is a common site of infection in MM patients.28 In addition, in Puerto Rico, there is a high incidence of respiratory diseases likely due to environmental factors like fungal spores,29 which may partially explain the elevated rate of death from respiratory causes in this population specifically. Future studies could investigate the influence of these co-morbid conditions on prognosis and cause of death in MM patients.

In this study, we used reliable population-level data collected over 26 years by the PRCCR and the US SEER program. The comparison of data from Puerto Rico with the Hispanic and non-Hispanic SEER populations is of interest because of the sociocultural relationship between Puerto Rico and the US, and to evaluate the similarities and differences between these populations with regards to MM outcomes. The lengthy study period allowed us to describe subtle variations in the rates of death from MM and non-MM causes over nearly three decades. Our analysis investigated time trends for MM-specific and non-MM deaths, which to our knowledge has not previously been reported in these populations. We also were able to assess whether recent declines in MM mortality already documented in some US population samples7 and in other countries30 were apparent in Puerto Rico.

There are also some limitations to our analysis, including the relatively small number of MM patients in the Puerto Rico database, which may have limited the power to detect temporal changes in less common causes of death. In addition, since data were only available through 2013, our findings may only partially reflect the influence of more recently approved therapies for MM.31 We also lacked individual-level information on variables such as smoking, alcohol, medication use, and obesity, which may contribute to risk of death from both MM and non-MM causes. We limited the analyses to the primary cause of death and ignored contributing causes, which may have over- or underestimated the number of deaths from MM, as patient deaths may have been incorrectly attributed to their MM. Differences in the approach to coding cause of death between populations may have resulted in misclassification of some less common causes of death, although we expect any impact on study results to be minimal.

Conclusions

Our data illustrate that people diagnosed with MM are still more likely to die from MM than from non-MM causes despite improvements in patient survival and treatment options during the study period. Furthermore, the decreases in MM-specific death in Puerto Rico have occurred at a lesser rate than in the SEER population, among both Hispanics and non-Hispanics, between 1987 and 2013 for reasons that are not immediately clear from this analysis. Nonetheless, death rates from MM do appear to have decreased in both Puerto Rico and in the SEER population. It is to be expected that as MM patients continue to survive longer, the management of other co-morbid conditions will be of increasing importance in this patient population, and that the distribution of such conditions will vary across different patient populations. Future studies are warranted to further clarify trends in co-morbidity and cause of death, to elucidate potential areas for improvement in care, and enhance the survival of patients with MM. Multi-center studies with detailed individual-level data are needed to further investigate the underlying explanations for our observed results, including examining associations between temporal changes to individual risk factors and treatment patterns with survival time and cause of death in MM patients.

Supplementary Material

Novelty & Impact Statements.

This study examined temporal trends in cause of death among patients with multiple myeloma in Puerto Rico and the US SEER population over 26 years. We found that although multiple myeloma-specific death decreased over time, it remains the predominant cause of death for individuals diagnosed with multiple myeloma in both populations. However, as multiple myeloma patients live longer due to improvements in treatment, the management of other co-morbid conditions may be of increasing importance.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded in part by the National Cancer Institute grant R03 CA199383 (MME). MME and MACA are supported in part by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant KL2TR001454 (MME), and TL1TR01454 (MACA).

Abbreviations:

- MM

multiple myeloma

- PRCCR

Puerto Rico Central Cancer Registry

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program

- APC

Annual Percent Change

- MGUS

Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance

- US

United States

References

- 1.Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, Blade J, Merlini G, Mateos MV, Kumar S, Hillengass J, Kastritis E, Richardson P, Landgren O, Paiva B, Dispenzieri A, Weiss B, LeLeu X, Zweegman S, Lonial S, Rosinol L, Zamagni E, Jagannath S, Sezer O, Kristinsson SY, Caers J, Usmani SZ, Lahuerta JJ, Johnsen HE, Beksac M, Cavo M, Goldschmidt H, Terpos E, Kyle RA, Anderson KC, Durie BG, Miguel JF. International myeloma working group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15, E538–E548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajkumar SV. Treatment of multiple myeloma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2011; 8, 479–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018; 68, 7–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2014, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/, based on November 2016 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batista JL, Birmann BM, Epstein MM. Chapter 29: Epidemiology of hematologic malignancies In: Loda M, Mucci L, Mittelstadt ML, Van Hemelrijck M, Cotter MB (Eds.) Pathology and epidemiology of cancer. Springer; 2017: 543–569 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lauby‑Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Bianchini F, Straif K. Body fatness and cancer — Viewpoint of the IARC working group. N Engl J Med 2016; 375, 794–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costa LJ, Brill IK, Omel J, Godby K, Kumar SK, Brown EE. Recent trends in multiple myeloma incidence and survival by age, race, and ethnicity in the United States. Blood Adv 2017; 1(4):282–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costello CL. Multiple myeloma in patients under 40 years old is associated with high-risk features and worse outcomes. Blood Adv 2013; 122:5359 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ailawadhi S, Aldoss IT, Yang D, Razavi P, Cozen W, Sher T, Chanan-Khan A. Outcome disparities in multiple myeloma: a SEER-based comparative analysis of ethnic subgroups. Br J Haematol 2012; 158, 91–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Ortiz AP, Fedewa SA, Pinheiro PS, Tortolero-Luna G, Martinez-Tyson D, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer Statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018; 68, 425–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinheiro PS, Callahan KE, Siegel RL, Jin H, Morris CR, Trapido EJ, Gomez SL. Cancer mortality in Hispanic ethnic groups. Cancer Epidem Biomar 2017; 26, 376–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mattei J, Tamez M, Ríos-Bedoya CF, Xiao RS, Tucker KL, Rodríguez-Orengo JF. Health conditions and lifestyle risk factors of adults living in Puerto Rico: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2018;18(1):491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zavala-Zegarra D, Tortolero-Luna G, Torres-Cintrón CR, Alvarado-Ortiz M, Traverso-Ortiz M, Román-Ruiz Y, Ortiz-Ortiz KJ. Cancer in Puerto Rico, 2008–2012 Puerto Rico Central Cancer Registry. San Juan, PR: 2015. Available at: http://www.rcpr.org/Portals/0/Informe%202008-2012.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 18 Regs Research Data, Nov 2015 Sub (1973–2013) <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment> - Linked To County Attributes - Total U.S., 1969–2016 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, released March 2016, based on the November 2015 submission. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute SEER*Stat software (seer.cancer.gov/seerstat) version <8.3.1>

- 16.Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 4.6.0.0 - April 2018; Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med 2000; 19, 335–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drawid A, Kaura S, Kiely D, Hussein MA, Kaman M, Gilra N, Durie BGM. Impact of novel therapies on multiple myeloma survival in the US: current and future outcomes. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2015; 15, E63 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2014. National vital statistics reports. National Center for Health Statistics. 2016; 65(4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pessoa de Magalhães Filho RJ, Crusoe E, Riva E, Bujan W, Conte G, Navarro Cabrera JR, Garcia DK, Vega GQ, Macias J, Oliveros Alvear JW, Royg M, Neves LA, Lopez Dopico JL, Espino G, Ortiz DR, Socarra Z, Fantl D, Ruiz-Arguelles GJ, Maiolino A, Hungria VTM, Harousseau JL, Durie B. Analysis of availability and access of anti-myeloma drugs and impact on the management of multiple myeloma in Latin American countries. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2018; S2152–2650(18)30361–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maiese EM, Evans KA, Chu BC, Irwin DE. Temporal trends in survival and healthcare costs in patients with multiple myeloma in the United States. Am Health Drug Benefits 2018; 11, 39–46 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bishaw A Poverty: 2010 and 2011 Community American Survey Briefs. 2012; 1–8. Available at: https://secf.memberclicks.net/assets/1-Website_Index/4-Resources/Docs/poverty_2010-11.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2015 American Community Survey, 1-Year Estimates. Available at: http://files.kff.org/attachment/Fact-Sheet-Puerto-Rico-Fast-Facts

- 25.Thomas A, Mailankody S, Korde N, Kristinsson SY, Turesson I, Landgren O. Second malignancies after multiple myeloma: from 1960s to 2010s. Blood 2012;119, 2731–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landgren O, Thomas A, Mailankody S. Myeloma and Second Primary Cancers. N Engl J Med 2011; 365, 2241–2242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kistler KD, Rajangam K, Faich G, Lanes S. Cardiac event rates in patients with newly diagnosed and relapsed multiple myeloma in US clinical practice. Blood 2012; 120:2916 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valković T, Gačić V, Ivandić J1, Petrov B, Dobrila-Dintinjana R, Dadić-Hero E, Načinović-Duletić A. Infections in Hospitalised Patients with Multiple myeloma: main characteristics and risk factors. Turkish J Hematol 2015; 32, 234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quintero E, Rivera-Mariani F, Bolaños-Rosero B. Analysis of environmental factors and their effects on fungal spores in the atmosphere of a tropical urban area (San Juan, Puerto Rico). Aerobiologia 2009; 26(2): 113–124 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Hayman SR, Buadi FK, Zeldenrust SR, Dingli D, Russell SJ, Lust JA, Greipp PR, Kyle RA, Gertz MA. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood 2008; 111, 2516–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajkumar SV Multiple myeloma: 2018 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol 2018; 93, 1091–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.