Abstract

Schlafen 11 (SLFN11) sensitizes cells to a broad range of anti-cancer drugs including platinum derivatives (cisplatin and carboplatin), inhibitors of topoisomerases (irinotecan, topotecan, doxorubicin, daunorubicin, mitoxantrone and etoposide), DNA synthesis inhibitors (gemcitabine, cytarabine, hydroxyurea and nucleoside analogues), and poly(ADPribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (olaparib, rucaparib, niraparib and talazoparib). In spite of their different primary mechanisms of action, all these drugs damage DNA during S-phase, activate the intra-S-phase checkpoint and induce replication fork slowing and stalling with single-stranded DNA segments coated with replication protein A. Such situation with abnormal replication forks is known as replication stress. SLFN11 irreversibly blocks replication in cells under replication stress, explaining why SLFN11-positive cells are markedly more efficiently killed by DNA-targeting drugs than SLFN11-negative cells. SLFN11 is inactivated in ~50% of cancer cell lines and in a large fraction of tumors, and is linked with the native immune, interferon and T-cells responses, implying the translational relevance of measuring SLFN11 expression as a predictive biomarker of response and resistance in patients. SLFN11 is also a plausible epigenetic target for reactivation by inhibitors of histone deacetylases (HDAC), DNA methyltransferases (DNMT) and EZH2 histone methyltransferase and for combination of these epigenetic inhibitors with DNA-targeting drugs in cells lacking SLFN11 expression. In addition, resistance due to lack of SLFN11 expression in tumors is a potential indication for cell-cycle checkpoint inhibitors in combination with DNA-targeting therapies.

Keywords: Schlafen 11, SLFN11, ATR, DNA-targeting agent, DNA damage response, replication stress, topoisomerases, cell cycle checkpoint, PARP inhibitors, drug resistance

1. Introduction of DNA-targeting anti-cancer drugs that engage SLFN11

Hallmarks of cancer cells include uncontrolled cell proliferation, genome instability and mutations (Hanahan & Weinberg, 2011). The uncontrollable proliferation of cancer cells has been targeted since the 1960’s by DNA-damaging agents and DNA synthesis inhibitors (together termed as DNA-targeting drugs in this review). One of the key lesions and rationale to target DNA is that collisions of replication forks into DNA damage generate lethal DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). Prolonged replication block by abrupt inhibition of DNA synthesis also induces fork collapse with DSBs. This is exacerbated as cancer cells tend to lose their G1 checkpoint due to lack of TP53, which allows cells damaged in G1-phase to progress into S-phase, thereby generating DSBs by replication collisions. Although DNA-targeting agents are not specific for cancer cells and can also damage normal replicating cells, recent genome-wide analyses reveal frequent deleterious mutations of DNA damage response and DNA repair genes in human cancer cells (Dietlein, Thelen, & Reinhardt, 2014), which explains the utility of DNA-targeting agents in these cancers based on the principle of synthetic lethality (Lord & Ashworth, 2017).

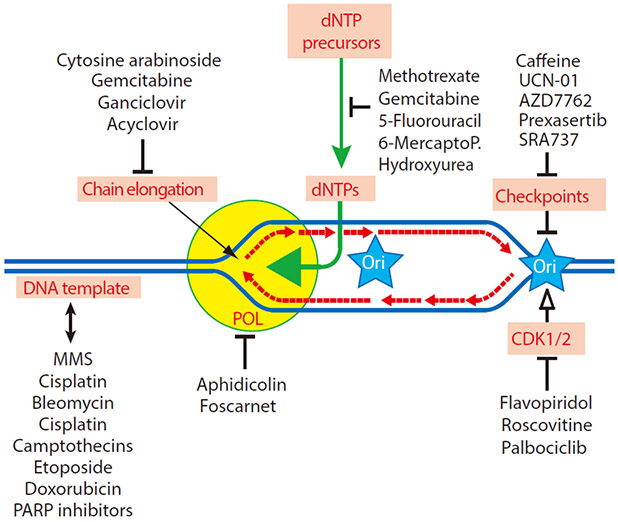

Despite the emergence of kinase inhibitors and immunotherapy in the cancer therapy landscape, DNA-targeting therapies remain highly beneficial for cancer treatment. DNA-targeting agents in the clinic, which engage SLFN11, include platinums (cisplatin, carboplatin and oxaliplatin), topoisomerase I (TOP1) inhibitors (camptothecin, topotecan, irinotecan and the indenoisoquinolines LMP400, LMP776 and LMP744), topoisomerase II (TOP2) inhibitors (etoposide, mitoxantrone, and doxorubicin), poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (olaparib, rucaparib, niraparib, talazoparib) and DNA synthesis inhibitors (hydroxyurea, gemcitabine, cytarabine and antifolates such as methoxate). Schlafen 11 (SLFN11) enhances the cytotoxicity of all these agents, and conversely, lack of SLFN11 expression tends to confer drug resistance. Before going into detail about SLFN11, we will briefly review how these drugs act and interfere with DNA replication (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scheme of the direct sites of drug action and pharmacological targets: deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), chain elongation, DNA polymerases (POL), DNA template alterations, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK1/2) and cell cycle checkpoints (Chk1 and Chk2). Representative drugs used in the clinic or as research tools are listed for each target. Ori: replication origin, 6-MercaptoP: 6-mercaptopurine, and UCN-01: 7-hydroxystaurosporine.

1.1. Platinums and topoisomerase inhibitors: replication template affecting agents

Cisplatin and carboplatin are among the most widely used chemotherapeutic agents in oncology. Both have a broad spectrum of clinical activity in numerous malignancies including gynecological cancers, germ cell tumors, head and neck cancer, thoracic cancers and bladder cancer (Ho, Woodward, & Coward, 2016). Platinum derivatives generate DNA adducts (monofunctional adducts, and bifunctional adducts consisting of intra- and inter-strand crosslink) (Kelland, 2007). Inter-strand crosslinks (ICL) are the most cytotoxic lesions because they physically block replication forks and require the coordinated action of multiple DNA repair pathways (Moldovan & D'Andrea, 2009; J. Murai, 2017) (Figure 2A).

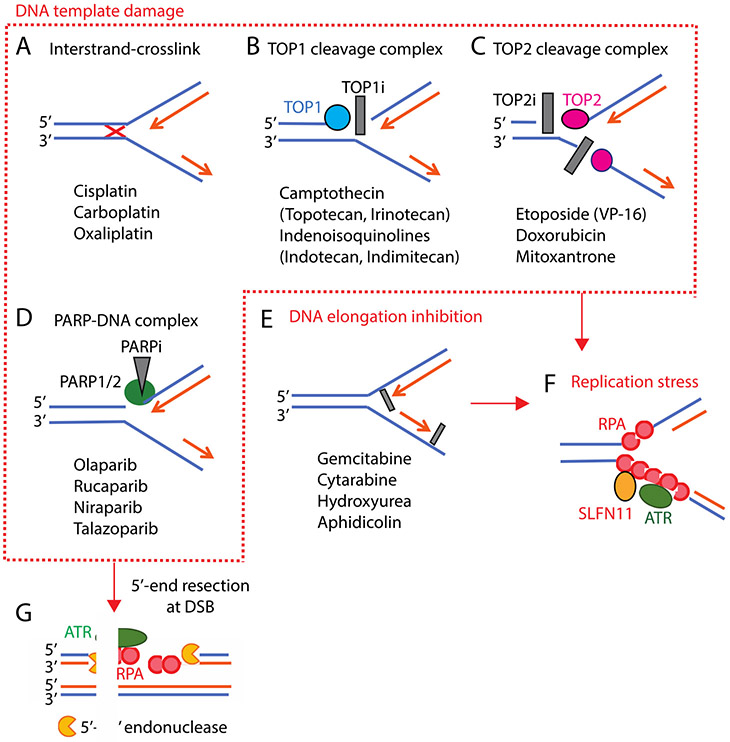

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of action of DNA-targeting agents that induce replication stress. Representative drugs are listed in each panel. A-D: Drugs targeting the DNA template. A: Platinums generate DNA interstrand-crosslink (red-cross). B and C: Topoisomerase I and II inhibitors (TOP1i and TOP2i, gray boxes) bind at the enzyme-DNA interface in the break sites and block the re-ligation of the TOP-DNA cleavage complexes (TOPcc). D: PARP inhibitors (PARPi) bind the catalytic pocket of PARP1 and PARP2 and trap PARP1 and PARP2 on the DNA, generating toxic PARP-DNA complexes. E: DNA elongation is blocked by reducing dNTP pools or inhibition of DNA polymerases. F: Under replication stress by various types of drugs, replication protein A (RPA) binds single-strand DNA and forms polymer where ATR is recruited and activated. RPA filaments also recruit SLFN11. G: The 5’-ends of DSB generated by fork collision are resected by the MRN (MRE11, RAD50, NBS1) complex and CtIP (RBBP8), and by DNase2 and EXO1. The 3’-single-stranded DNA tails are coated by RPAs, where ATR is recruited and activated.

DNA topoisomerases are the targets of widely used anti-cancer and anti-bacterial drugs (Nitiss, 2009; Pommier, 2013; Pommier, Leo, Zhang, & Marchand, 2010). TOP1 relieves DNA torsional stress during replication and transcription by cleaving one strand of duplex DNA within TOP1-DNA cleavage complexes (TOP1cc), allowing the untwisting of supercoiled DNA. TOP1 inhibitors kill malignant cells by trapping TOP1cc, leading to their conversion to DSBs upon collision of replication forks in replicating cancer cells (Strumberg, et al., 2000) (Figure 2B). Two TOP1 inhibitors, topotecan and irinotecan, are approved across the world as anti-cancer agents. Because of their limitations (chemically instability, limited drug accumulation in drug efflux overexpressing cells, reversible trapping of TOP1cc, and severe diarrhea [for irinotecan]) (Pommier & Cushman, 2009), a novel chemical class of TOP1 inhibitors, the indenoisoquinolines [LMP400 (indotecan, NSC724998), LMP776 (indimitecan, NSC725776) and LMP744 (MJ-III-65, NSC706744)] (Antony, et al., 2007; Burton, et al., 2018; Pommier & Cushman, 2009) have been developed. LMP400 recently completed phase 1 clinical trials with demonstrable target engagement (Kummar, et al., 2016), and is now poised for Phase 2 trials. LMP776 is finishing phase 1 and LMP744 is beginning phase 1 clinical trials based on activity in dogs with primary lymphomas (Burton, et al., 2018).

Unlike TOP1, TOP2 cleaves both strands of the DNA simultaneously to allow another DNA duplex to pass through the TOP2-linked DSB (Pommier, Sun, Huang, & Nitiss, 2016). This enables TOP2 not only to relax supercoiling but also to disentangle DNA knots and catenanes at the end of DNA replication. Although the catalytic function of TOP2 is critical during mitosis, TOP2 cleavage complexes (TOP2cc) are generated throughout the cell cycle including during G1 and S. Hence, TOP2 inhibitors that stabilize TOP2cc (etoposide, mitoxantrone, daunorubicin, doxorubicin, epirubicin and idarubicin) induce DSBs directly in all phases of the cell cycle. TOP2 inhibitors do not require S-phase to induce damage, but ongoing replication enhances their cytotoxicity (Figure 2C) (Vesela, Chroma, Turi, & Mistrik, 2017). While etoposide (VP-16, Vepesid) is highly selective for TOP2cc (Long & Stringfellow, 1988; Ross, Rowe, Glisson, Yalowich, & Liu, 1984), the anthracyclines (doxorubicin, daunorubicin, epirubicin and idarubicin) not only trap TOP2cc but also kill cells by intercalation and generation of oxygen radicals (Doroshow, 1996).

1.2. PARP inhibitors: PARP1- and PARP2-trapping and DNA repair inhibition

Poly(ADPribose) polymerases (PARPs) belong to a large 17-member family of enzymes that share a common ADP-ribosyl transferase motif. Nuclear PARP1 and PARP2 are allosterically activated by their binding to DNA breaks, which induces the recruitment of components of the DNA repair machinery (Pommier, O'Connor, & de Bono, 2016). NAD+ serves as the building block for the PAR polymers (PARylation). PARylation occurs on PARP1 and PARP2 themselves, histones and multiple proteins. All clinical PARP inhibitors are competitive NAD+ inhibitors for the catalytic pockets of PARP1 and PARP2. They were initially developed to prevent single-strand break (SSB) repair and for combination therapy with SSB-inducing agents including ionizing radiation, alkylating agents, and TOP1 inhibitors [reviewed in (Lord & Ashworth, 2017; Pommier, O'Connor, et al., 2016)].

The discovery of the synthetic lethality of PARP inhibitors as single agents in BRCA (homologous recombination)-deficient cells, was interpreted initially as an inhibition of PARylation at DNA damaged sites, resulting in an accumulation of SSBs that are converted into lethal DSBs upon replication fork collisions due to lack of homologous recombination (HR) (Bryant, et al., 2005; Farmer, et al., 2005). Further studies showed, however, that PARP inhibitors with equivalent potency as PARylation inhibitors have widely different cytotoxicity (J. Murai, et al., 2012; J. Murai, et al., 2014; J. Murai & Pommier, 2015; Shen, et al., 2013), and that this differential cytotoxicity was driven by the potency of the drugs to stabilize PARP1- and PARP2-DNA complexes at SSBs (PARP-trapping, Figure 2D) (J. Murai, et al., 2012; J. Murai, et al., 2014). This explained why PARP1 is required for PARP inhibitors cytotoxicity and why lack of PARP1 confers high resistance to PARP inhibitors (J. Murai, et al., 2012; Pommier, O'Connor, et al., 2016). Hence, the current view is that PARP inhibitors act as DNA targeting agents by PARP-trapping as well as DNA repair inhibitors by catalytic inhibition of PARP1/2. The PARP trapping mechanism also explains the different levels of cytotoxicity of different PARP inhibitors as single agents in BRCA-proficient cancer cells (J. Murai, et al., 2012; J. Murai & Pommier, 2019). A recent study also showed that PARP is required for the repair of abortive Okasaki fragments, which raises the possibility that PARP inhibitors target replication by generating breaks at Okasaki fragments (Hanzlikova, et al., 2018).

Four PARP inhibitors are now clinically approved in the United States as single agents: olaparib for patients with germline BRCA-mutated breast and advanced ovarian cancers who have previously been treated with chemotherapy (Robson, et al., 2017); rucaparib for patients with germline and/or somatic BRCA-mutated advanced ovarian cancer treated previously with chemotherapies (Coleman, et al., 2017); and both olaparib and niraparib are approved as maintenance therapies regardless of BRCA mutation in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer, who are in a complete or partial response to platinum-based chemotherapy (Ledermann, et al., 2012; Mirza, et al., 2016a). Talazoparib, the most potent PARP-trapping drug, provided a significant benefit over standard chemotherapy with respect to progression-free survival in patients with advanced breast cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation (Litton, et al., 2018), and has recently been approved for breast cancer with germline BRCA1/2 mutated, HER2-negative locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer.

1.3. DNA synthesis inhibitors: direct block of DNA polymerization

Because cancer progression depends on cellular proliferation, DNA synthesis inhibitors were among the first effective chemotherapeutic agents developed (Hitchings & Elion, 1985). Prolonged replication fork stalling leads to lethal replisome disassembly and fork breakage (Branzei & Foiani, 2010). Replication itself is targeted by anti-cancer drugs in several ways. Gemcitabine and cytarabine (also known as cytosine arabinoside or ara-C) are nucleoside analogues. They stall replication after their incorporation by DNA polymerases (Figure 2E). Since ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) catalyzes the formation of deoxyribonucleotides from ribonucleotides, pharmacological inhibition of RNR by hydroxyurea (HU) impairs DNA replication by exhausting dNTP pool (Nordlund & Reichard, 2006). Hydroxyurea is a well-established inhibitor of RRM2 and gemcitabine acts also as an inhibitor of RRM1. Aphidicolin is a tetracycline diterpenoid antibiotic that interferes with DNA replication by inhibiting DNA polymerase α, ε, and δ, but has limited use in clinical practice owing to its low solubility (Cheng & Kuchta, 1993) (Vesela, et al., 2017).

2. Replication stress, extended RPA filaments and S-phase checkpoint activation

Although the DNA-targeting agents described above induce different types of DNA lesions (Figure 2A-E), they have in common to stall DNA synthesis and/or replication forks, which is referred to as replication stress (Lecona & Fernandez-Capetillo, 2018; Vesela, et al., 2017). One of the molecular characteristics of replication stress is the formation of extended replication protein A (RPA) filaments on single-stranded DNA segments within stressed replicons (Figure 2F). Typically, replication stress induced by dNTP depletion (as in response to HU) or polymerase block (as chain termination by Ara-CTP) or DNA template damages uncouples the replicative helicase (CDC45, MCM2-7 and GINS) CMG complex and DNA polymerases, resulting in RPA filaments accumulating on the ssDNA segments between the helicases and polymerases (Figure 2F). ssDNA coated with RPA is also generated during homologous recombination after 5’-end resection of one the broken DNA strands (Figure 2G).

It is well-established that ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein kinase (ATR) is recruited by RPA on the ssDNA coated filaments, and that it is further activated by TOPBP1 (Topoisomerase Binding Protein 1) at stressed replication forks as well as at DNA-end resection sites (Branzei & Foiani, 2008; Lecona & Fernandez-Capetillo, 2018; Zeman & Cimprich, 2014) (Figures 2F and G). In turn, ATR activates the S-phase checkpoint and its key protein kinase CHEK1, which slows down and stabilizes replication forks, and prevents replication origin firing (Cliby, et al., 1998; Friedel, Pike, & Gasser, 2009; Lecona & Fernandez-Capetillo, 2018; Seiler, Conti, Syed, Aladjem, & Pommier, 2007). By transiently stopping replication, the S-phase checkpoint promotes DNA repair and prevents premature mitosis, thereby reduces replication stress and maintains genomic stability (Lecona & Fernandez-Capetillo, 2018; Nam & Cortez, 2011; Zeman & Cimprich, 2014).

Pharmacological inactivation of the S-phase checkpoint and replication stress response (Lecona & Fernandez-Capetillo, 2018) are actively pursued by major pharmaceutical companies. ATR inhibitors presently in clinical trials include M6620 (also referred to as VX-970 or VE-822, a derivative of VE-821), AZD6738 and BAY1895344. Inhibitors of CHEK1 (the downstream substrate of ATR) have been developed earlier, with UCN-01, CHIR-124 and AZD7762. While the clinical development of these early CHEK1 inhibitors was abandoned for lack of selectivity, poor pharmacokinetics and toxicity, there are currently two CHEK1 inhibitors in clinical trials: prexasertib (LY2606368) and SRA737. Both ATR and CHEK1 inhibitors cause replication stress through unscheduled firing of replication origins and uncoupling of the overstimulated replication helicases from polymerases, which induces massive RPA loading between the CMG helicase and DNA polymerases (Claus Storgaard Sørensen, 2011; Josse, et al., 2014; Karnitz & Zou, 2015; King, et al., 2015; Syljuasen, et al., 2005).

3. SLFN11, the newly discovered executioner of the replication stress

3.1. Paucity of predictive biomarkers for DNA-targeting agents

Platinums and topoisomerase inhibitors remain among the most prescribed anti-cancer drugs, and PARP inhibitors are becoming widely used not only for ovarian, but also for more common cancers such as breast and prostate neoplasms. Yet, no specific molecular and cellular biomarkers predicting differential sensitivity to platinums and topoisomerase inhibitors are being used in the clinic. As for PARP inhibitors, mutations in the BRCA genes and measures of homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) are used to identify potential individual patient responders. HRD assays are based on analyzing genomic defects (mutational burden, Myriad HRD score, and mutations in DNA damage response [DDR] genes).

Although the synthetic lethality of PARP inhibitors for BRCA-deficient cells is an elegant strategy (Lord & Ashworth, 2017), not all BRCA-deficient tumors respond to PARP inhibitors (Gelmon, et al., 2011; Tutt, et al., 2010). PARP inhibitors are also active beyond HRD (Lord, Tutt, & Ashworth, 2015; J. Murai, et al., 2012; J. Murai & Pommier, 2019; O'Connor, 2015; Zimmermann, et al., 2018), and recent trials have shown benefit in patients without detectable HRD (Lok, et al., 2017; Mirza, et al., 2016b). Thus, availability of robust biomarkers is an unmet need to optimize the efficacy of DNA-targeting agents and maximize their clinical efficacy (Reinhold, Thomas, & Pommier, 2017).

3.2. Discovery of SLFN11 as a predictive biomarker for a broad range of DNA-targeting agents

The US National Cancer Institute NCI-60 was the first cancer cell line panel set for drug discovery (Chabner & Roberts, 2005). It also turned out to provide new ways for elucidating drug molecular mechanisms of action (Paull, et al., 1989; Scherf, et al., 2000). The NCI-60 cell lines are derived from nine tissues of origin: breast, colon, skin, blood, central nervous system, lung, prostate, ovary and kidney. The NCI-60 is the most annotated set of cancer cell lines with whole genome expression, mutation profiles, DNA methylation profiles, gene copy numbers and drug responses for more than 200,000 compounds as well as a variety of molecular and cellular processes (Reinhold, Sunshine, Varma, Doroshow, & Pommier, 2015; Reinhold, Varma, et al., 2017; Sousa, et al., 2015; Zeeberg, et al., 2012). The NCI-60 databases together with the Broad and Sanger Institutes cancer cell line databases (CCLE, CTRIP and GDSC) are now available to examine correlation between genomic parameters and the activity of ~200,000 compounds (CellMinerCDB: https://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminercdb/) (Rajapakse, et al., 2018).

Based on the NCI-60 genomic and pharmacological databases (Paull, et al., 1989; Reinhold, et al., 2015; Reinhold, Thomas, et al., 2017; Reinhold, Varma, et al., 2017; Scherf, et al., 2000) and on the development of the CellMiner bioinformatics tools (Rajapakse, et al., 2018; Reinhold, et al., 2015; Reinhold, Thomas, et al., 2017; Reinhold, Varma, et al., 2017) (http://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminer), our group discovered Schlafen 11 (SLFN11) as an unanticipated genomic determinant of response to TOP1 inhibitors, TOP2 inhibitors, alkylating agents including platinum derivatives and DNA synthesis inhibitors in 2012 (Nogales, et al., 2016; Sousa, et al., 2015; Zoppoli, et al., 2012). Independently, SLFN11 was identified as a predictive genomic biomarker for response to the TOP1 inhibitors, irinotecan and topotecan, in the larger database of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) at the Broad Institute and found highly expressed in Ewing’s sarcoma cell lines (Barretina, et al., 2012). Thus, SLFN11, a very little characterized gene before, suddenly got to the spotlight as a critical player in cancer therapeutics in 2012.

The relevance of SLFN11-dependent drug sensitivity was extended to PARP inhibitors through the finding of highly significant and causal link between high SLFN11 expression and response to PARP inhibitors in the NCI-60 (J. Murai, et al., 2016). While BRCA-deficiency by homozygous deleterious mutation or lack of expression is only found in one of the NCI-60 cell lines (Sousa, et al., 2015), nearly half of the cell lines respond to the most potent PARP inhibitor talazoparib (J. Murai, et al., 2014). Conversely, cells that do not express SLFN11 were found highly resistant to talazoparib and this correlation was validated in xenograft models (J. Murai, et al., 2016). More recent studies in small cell lung cancer (SCLC) also identified SLFN11, but not HR genes or HRD scores as a consistent determinant of response to PARP inhibitors (Lok, et al., 2017; Stewart, et al., 2017). Thus, SLFN11 is a highly prevalent biomarker for PARP inhibitors in addition to and independently of BRCA1/2 mutation and HRD in preclinical models (J. Murai, et al., 2016).

It is important to note that the SLFN11-dependent drug sensitization is specific for drugs that induce replication stress and that SLFN11 expression is not correlated with the activity of protein kinase or tubulin inhibitors (Reinhold, Varma, et al., 2017; Zoppoli, et al., 2012). It is also notable that SLFN11 silencing (by siRNA or gene-knockout using CRISPR/Cas9) does not have obvious impact on cell cycle and viability in the absence of exogenous DNA damage (J. Murai, et al., 2016; J. Murai, et al., 2018).

3.3. The Schlafen family

Schlafen (“sleep” in German and abbreviated SLFN) genes were first discovered in mouse as a family of genes preferentially expressed in lymphoid tissues that ablate cell growth while enabling proper thymus development (Schwarz, Katayama, & Hedrick, 1998). Schlafen genes are only found in mammals, and have been shown to regulate biological functions including cellular proliferation, induction of immune response and suppression of viral replication (Mavrommatis, Fish, & Platanias, 2013).

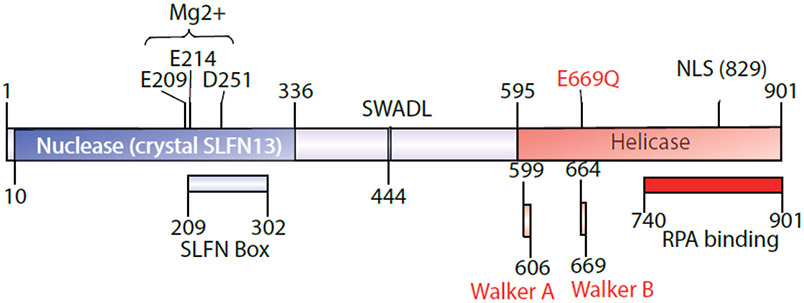

The murine Slfn family consists of 10 genes clustered on chromosome 11 (Slfn1, 1L, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 10, and 14), and the human SLFNs consists of 5 genes (SLFN5, 11, 12, 13, and 14) clustered on chromosome 17. All SLFNs contain a Slfn box, a domain not found in other proteins and whose function is not well defined (Geserick 2004, Neumann 2008). While SLFN12 lacks a helicase domain, the remaining human SLFNs harbor a helicase domain in their C-terminus (Geserick, Kaiser, Klemm, Kaufmann, & Zerrahn, 2004; Mavrommatis, et al., 2013). SLFN11 is a 901 amino acid residue polypeptide with two main domains (Figure 3). The N-terminus nuclease domain has high similarity with SLFN13, which was recently crystallized and shown to cleave tRNA (Yang, et al., 2018). The C-terminus helicase contains the nuclear localizing signal (Figure 3). Consistently, immunostaining of SLFN11 shows prominent nuclear localization (Gardner, et al., 2017; J. Murai, et al., 2016; J. Murai, et al., 2018; Stewart, et al., 2017; Zoppoli, et al., 2012). In spite of its sequence conservation among the SLFN genes, SLFN11 consistently shows the most significant correlation with DNA-targeting drugs among the human SLFN family of genes (Stewart, et al., 2017) (http://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminercdb) (Rajapakse, et al., 2018).

Figure 3.

Scheme of the domain structure of SLFN11 (901 amino acids). SLFN11 has two main domains: 1/ the N-terminus nuclease domain is highly conserved with SLFN13, which acts as ribonuclease for t-RNA (Yang, et al., 2018); 2/ the C-terminus helicase domain contains Walker A and Walker B motifs and the nuclear localization signal (NLS). The point mutation at E669 into Q669 disrupts the function of SLFN11 for chromatin opening and drug sensitization, yet SLFN11-E669Q retains chromatin binding ability (J. Murai, et al., 2018). The RPA binding domain is essential for SLFN11 recruitment to chromatin in response to DNA damage (Mu, et al., 2016). The SLFN box and SWADL domains are conserved across all human SLFNs (5, 11, 12, 13 and 14), although their functions are not characterized.

3.4. Pre-clinical and clinical data establishing SLFN11 as a determinant of drug response

The importance of SLFN11 for drug sensitivity (Barretina, et al., 2012; J. Murai, et al., 2016; J. Murai & Pommier, 2019; J. Murai, et al., 2018; Nogales, et al., 2016; Sousa, et al., 2015; Tang, et al., 2015; Tang, et al., 2018; Zoppoli, et al., 2012) has recently been validated in various tumor models and tumors from patients. SLFN11 determines the anti-proliferative activity of SN-38 (a camptothecin derivative) in colorectal cancer cell lines (Tian, et al., 2014), and cytotoxicity of SN-38 inversely correlates with SLFN11 mRNA expression in 20 Ewing sarcoma cell lines (Kang, et al., 2015). SLFN11 suppresses growth of human colorectal cancer cells in mice (He, et al., 2017). Ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) inhibitors arrest Ewing sarcoma cells, in part, because of their high levels of SLFN11 (Goss & Gordon, 2016). By generating paired chemo-naive and chemo-resistant SCLC patient-derived xenograft models, Gardner et al. found that SLFN11 was silenced in acquired chemo-resistance tumors (Gardner, et al., 2017). Using a high-throughput, integrated proteomic, transcriptomic, and genomic analysis of SCLC patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) and profiled cell lines, Stewart et al. reported that high levels of SLFN11 predict response to cisplatin and PARP inhibitors (Stewart, et al., 2017).

In the clinic, analyses of the Cancer Genome Atlas databases (TCGA) show that high SLFN11 expression predicts overall survival in ovarian cancer patients treated with cisplatin-containing regimens (Zoppoli, et al., 2012). High SLFN11 expression predicts better survival for patients with KRAS exon 2 wild-type colorectal cancer after treatment with adjuvant oxaliplatin-based treatment (Deng, et al., 2015). In a randomized trial of temozolomide with veliparib or placebo in relapsed SCLC patients, patients with SLFN11-positive tumors treated with temozolomide and veliparib, which combination produces PARP-DNA complexes (replication stress), had significantly prolonged progression-free survival (5.7 months vs. 3.6 months) and overall survival (12.2 months vs. 7.5 months) compared with patients with SLFN11-negative tumors who received the same combination (Pietanza, et al., 2018). Notably, no such effect was observed based on SLFN11 expression among patients who received temozolomide and placebo, which combination does not cause PARP-trapping (replication stress), suggesting SLFN11 as a predictive biomarker of response specifically to PARP-trapping combinations.

3.5. Action of SLFN11 as executioner of replication stress

Considering features of the drugs exhibiting SLFN11-dependent sensitivity, replication stress is a common mechanism(s) engaging SLFN11 to kill cancer cells. Insights into the molecular functions of SLFN11 have been provided by recent studies (Li, et al., 2018; Marechal, et al., 2014; Mezzadra, et al., 2019; J. Murai, et al., 2016; J. Murai, et al., 2018; Zoppoli, et al., 2012).

The first molecular connection between SLFN11 and replication stress was the co-immunoprecipitation of SLFN11 with RPA1, a replication and repair protein binding to ssDNA generated by replication stress and DNA excision prior to homologous recombination and nucleotide excision repair (Marechal, et al., 2014). Mu et al. confirmed that the C-terminus of SLFN11 interacts directly with RPA1 and revealed that SLFN11 is recruited to sites of DNA damage in an RPA1-dependent manner (Figure 3) (Mu, et al., 2016). They proposed that SLFN11 inhibits checkpoint maintenance and HR repair by promoting the destabilization of the RPA-ssDNA complex, thereby sensing cancer cell lines with high SLFN11 to DNA-damaging agents.

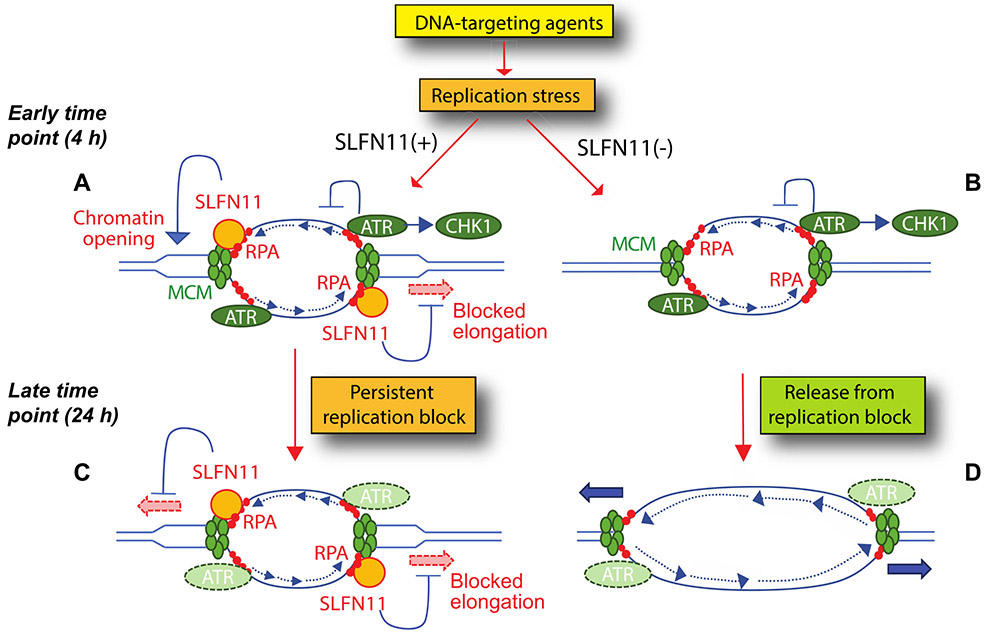

Our group showed that SLFN11 induces lethal replication block in response to a broad type of DNA-targeting agents (J. Murai, et al., 2016; J. Murai, et al., 2018; Zoppoli, et al., 2012), and that SLFN11 acts in parallel with the ATR- CHEK1-mediated S-phase checkpoint. SLFN11-CMG-mediated cell cycle arrest is permanent and lethal while the ATR-CHEK1-mediated S-phase checkpoint is transient and enables DNA repair and cell survival (J. Murai, et al., 2016) (Figure 4). We recently elucidated some key molecular mechanisms by which SLFN11 irreversibly blocks replication. Upon replication damage and stress, RPA filaments are generated on single-stranded DNA both at resected DNA ends and at stressed replication forks (Figures 2 & 4). In the latter case, single-stranded DNA is generated by the uncoupling of the DNA helicase (CMG complex) and the DNA polymerase complex. We confirmed that SLFN11 is recruited to chromatin by binding to RPA and showed that SLFN11 also binds MCM3 and blocks replication while chromatin is loosen or opened by SLFN11 (Figures 3 & 4). These steps happen progressively within 4 hours after DNA damage as SLFN11 is recruited to chromatin (J. Murai, et al., 2018). The ATPase activity of SLFN11 is not required for the recruitment of SLFN11 to chromatin but required for SLFN11 to block replication fork progression and to open chromatin. Although the mechanisms of replication block by the putative ATPase activity of SLFN11 are not fully understood, a plausible scenario is that once SLFN11 binds stressed replication forks, chromatin becomes open in a SLFN11-dependent process ahead of the MCM helicase, which distorts the appropriate structure for the MCM complex and blocks fork progression (Figure 4). Under normal conditions, replication forks only form short ssDNA segments coated with RPA, and, which limits or preclude SLFN11 access, explaining why SLFN11 does not interfere with normal replication.

Figure 4.

Molecular model of SLFN11-induced replication fork block in response to replication stress at early time points (A, B) and later time points (C, D). A: In SLFN11-expressing cells, both ATR and SLFN11 are recruited to stressed replication forks by replication protein A (RPA)-coated single-stranded DNA. SLFN11 also binds MCM3 (a component of CMG replicative helicase) and promotes chromatin opening. B: in SLNF11-negative cells, ATR alone exerts its replication effects by transiently blocking fork elongation and by activating CHEK1, which also blocks forks and origin firing (not shown). C: at later time, SLFN11 bound to chromatin produces a persistent replication block that irreversibly arrest cell cycle and kills cells. D: in SLFN11-negative cells, replication block by the ATR-CHEK1 is transient and replication can resume after a while.

Although the SLFN11-dependent drug sensitivity is linked to its putative helicase activity and RPA binding (Mu, et al., 2016; J. Murai, et al., 2018), which are assigned to the C-terminus domain of SLFN11 (Figure 3), Li et al. recently revealed that SLFN11-dependent cleavage of type II tRNAs in response to DNA damage suppresses translation of high TTA (Leu) codon usage-proteins such as ATR, which restores drug sensitivity to DNA damaging agents (Li, et al., 2018). This mechanism is consistent with the conservation of the N-terminal motifs of SLNF11 and SLFN13 in the context of a recent structural studies demonstrating that SLFN13 cleaves tRNAs (Yang, et al., 2018).

Additionally, a recent study showed that SLFN11 mediates T cell-mediated cytotoxicity in tissue-dependent manner (Mezzadra, et al., 2019). Mezzadra et al. found that SLFN11 enhanced the T cell-mediated cytotoxicity in the HLA-A2-positive haploid human cell line HAP1 but not in two other cell lines, while SLFN11 enhanced sensitivities to DNA damaging agents across the three cell lines. Hence the downstream effect of interferon-γ can be cell-type dependent. Since SLFN11 is supposed to be multifunctional (chromatin opening, helicase activity, tRNA binding, native immune response and others), further studies are warranted to clarify the potentially multiple mechanisms by which SLFN11 enhances the killing of cancer cells, possibly through direct chromatin effects, indirect t-RNA alterations and native immune response.

3.6. Regulation of SLFN11 expression

Approximately 50% of all cancer cell lines do not express SLFN11 making its expression bimodal; i.e. cells either express or do not express SLFN11 (Barretina, et al., 2012; J. Murai, et al., 2018; Rajapakse, et al., 2018; Sousa, et al., 2015; Tang, et al., 2018; Zoppoli, et al., 2012), and among those that have the highest expression stand Ewing’s sarcoma cell lines (Barretina, et al., 2012). Also, protein expression is highly correlated with gene expression (Zoppoli, et al., 2012). The expression of SLFN11 is regulated: 1/ epigenetically; 2/ transcriptionally; and 3/ in native immune response to viral infections and interferon (Figure 5). SLFN11 expression is not due to changes in DNA copy number across cancer cell lines (Rajapakse, et al., 2018; Reinhold, Varma, et al., 2017), and mutations of SLFN11 are only found at 0.7 % of ~64,000 samples in 216 studies (cbioportal.org) (http://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminercdb). Yet, mutations of SLFN11 at low frequency (7.7%) were reported in relapsed Ewing sarcomas that consistently shows a 2- to 3-fold increased number of mutations (Agelopoulos, et al., 2015) and deep sequencing of SLFN11 in patients after relapse to chemotherapy has not been performed.

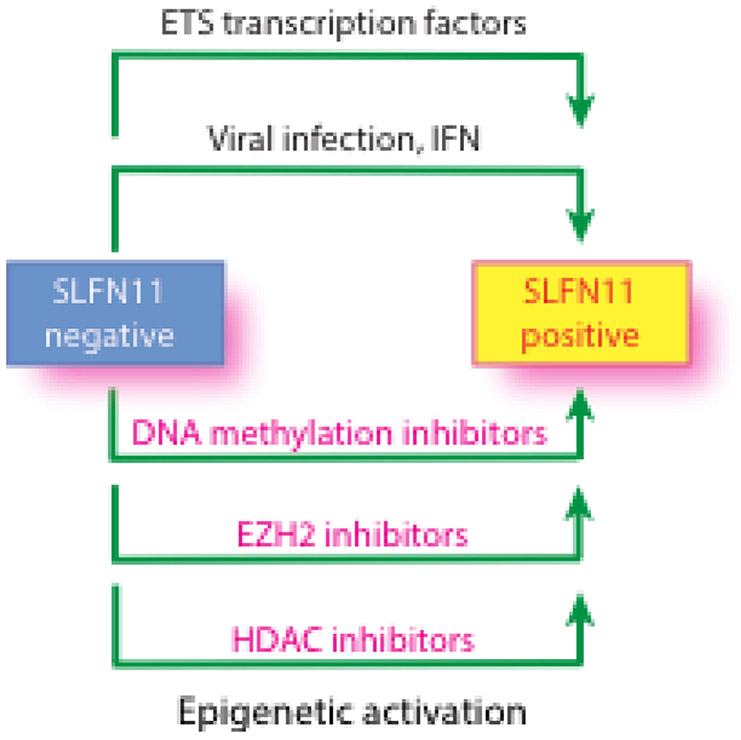

Figure 5.

Reactivation SLFN11 through ETS transcription factors, viral infection, interferon (IFN) and epigenetic reprogramming. Three types of epigenetic inhibitors (DNA methylation inhibitors, inhibitors for EZH2 [a histone H3K27 methyltransferase] and class I Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors) are reported to re-activate SLFN11 in epigenetically inactivated SLFN11-negative cells (see text for details and references).

Three epigenetic mechanisms have been shown to suppress SLFN11 expression: promoter methylation (Nogales, et al., 2016; Reinhold, Varma, et al., 2017), histone deacetylation (Tang, et al., 2018) and histone methylation by the polycomb repressor complex (PRC) (Stewart, et al., 2017). SLFN11 is among the genes with the highest correlation (at the top 94th percentile) between promoter methylation and expression across over 1,000 cancer cell lines including the NCI-60 and the Sanger-Mass General cancer cell lines (http://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminercdb) (Rajapakse, et al., 2018). Promoter hypermethylation accounts for approximately half of the cell lines that do not express SLFN11. SLFN11 methylation is significantly correlated with resistance to widely used clinical drugs that target DNA replication including talazoparib, olaparib, cisplatin, carboplatin, topotecan, irinotecan, etoposide, hydroxyurea, gemcitabine and cytarabine (Nogales, et al., 2016; Reinhold, Varma, et al., 2017) across cancer cell line databases (http://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminercdb) (Rajapakse, et al., 2018). SLFN11 is also methylated in 56% (71/128) of primary colorectal cancer samples, and the methylation of the SLFN11 is a marker of poor prognosis and platinum resistance in colorectal cancer (He, et al., 2017). SLFN11 hypermethylation is an independent prognostic factor in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and ovarian cancer who received platinum-based chemotherapy. In both tumors, SLFN11 hypermethylation is significantly associated with shorter progression-free survival. Resistance to cisplatin or PARP inhibitors in SCLC is associated with silencing of SLFN11 caused by EZH2, a histone methyltransferase targeting H3K27me3 and catalytic component of PRC2 (Gardner, et al., 2017; Stewart, et al., 2017). Accordingly, EZH2 inhibition prevents acquisition of chemo-resistance and improves chemotherapy efficacy in SCLC (Gardner, et al., 2017).

Ewing sarcoma, which is characterized by translocations generating the chimeric transcription factor EWS-FLI1, has notably the highest SLFN11 expression among 4,103 primary tumor samples spanning 39 lineages (Barretina, et al., 2012). One of mechanisms of transcriptional activation in Ewing sarcomas is the binding of EWS-FLI1 at ETS consensus sites on the SLFN11 promoter (Tang, et al., 2015). The correlated expression between SLFN11 and FLI1 extends to leukemia, pediatric, colon, breast, and prostate cancers (Tang, et al., 2015).

SLFN11 as well as SLFN5 are induced by IFN-β, IFN-γ, poly-inosine-cytosine or poly dAdT (Li, et al., 2012; Mezzadra, et al., 2019). SLFN11 expression is also positively correlated with Type I IFN pathway genes, PDL1 and IL6 in treatment-naïve SCLC patient tumors (Stewart, et al., 2017). Thus, SLFN11 is likely to contribute to anti-viral and native immune functions. One of the mechanisms proposed for the antiviral activity of SLFN11 is its binding to a subset of rare transfer RNAs (tRNAs), which specifically abrogates the production of retroviruses such as human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) by selectively blocking the expression of viral proteins in a codon usage-dependent manner (Li, et al., 2012).

3.7. Reactivation of SLFN11 expression and overcoming resistance mediated by low SLFN11 expression using ATR inhibitors

The epigenetic silencing of SLFN11 raises the question of whether epigenetic drugs can derepress SLFN11 and sensitize SLFN11-inactivated cancer cells to DNA-targeting agents (Figure 5). Consistent with this possibility, the DNA demethylating drug, 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (decitabine) reverses SLFN11 hypermethylation, thereby re-sensitizing cells to platinum drugs through SLFN11 re-expression (Nogales, et al., 2016). The EZH2 inhibitor EPZ011989 was also shown to reactivate SLFN11 expression and enhance the cytotoxicity and anti-tumor activity of topotecan in SCLC cells and PDX murine models (Gardner, et al., 2017). Another epigenetic therapeutic combination is with class I Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors (romidepsin, entinostat and depsipeptide), but not the class II HDAC inhibitor (roclinostat), which overcome resistance to DNA-targeted agents by epigenetic activation of SLFN11 expression in cells that do not exhibit SLFN11-promoter hypermethylation (Tang, et al., 2018). SLFN11 expression was also enhanced in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with circulating cutaneous T-cell lymphoma treated with depsipeptide (romidepsin) (Tang, et al., 2018).

Another approach to overcome the resistance of SLFN11-negative cancer cells to DNA-damaging drugs could be by combining the DNA- and replication-targeting agents with ATR inhibitors. Several ATR inhibitors are in advanced clinical development [VX-970 (M6620) and AZD6738]. It is likely that the greatest therapeutic benefit from these agents will be in combination therapy. Because cells that lack SLFN11 rely primarily on ATR for adapting to replication stress, a plausible strategy, which has been validated in preclinical models (J. Murai, et al., 2016; J. Murai, et al., 2018) is to combine ATR inhibitors with PARP and TOP1 inhibitors in SLFN11-negative tumors.

4. Translating SLFN11 to the clinic

Consistent with the cell line database (see above), SLFN11 expression demonstrates a broad range of expression in a wide range of cancer types in the TCGA database (Tang, et al., 2018). Also, the expression range of SLFN11 tends to be greater in tumors than in adjacent normal tissues (Zoppoli, et al., 2012). These observations together with the emerging data linking SLFN11 expression with tumor response suggest the relevance of measuring SLFN11 as a predictive biomarker of response to the widely used DNA-targeting agents shown in Figure 1, including platinum drugs, antimetabolites, topoisomerase inhibitors, alkylating agents and PARP inhibitors. Among cancer types, SCLC may provide a good testing ground because SLFN11 has a range of expression in primary SCLC tumors (Lok, et al., 2017) and across the 51 SCLC cell lines with bimodal distribution (Polley, et al., 2016; Stewart, et al., 2017) (http://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminercdb). Furthermore, the standard first-line treatment for metastatic SCLC consists of a platinum, cisplatin or carboplatin, generally paired with the TOP2 inhibitor etoposide, all of exhibit SLFN11-dependency.

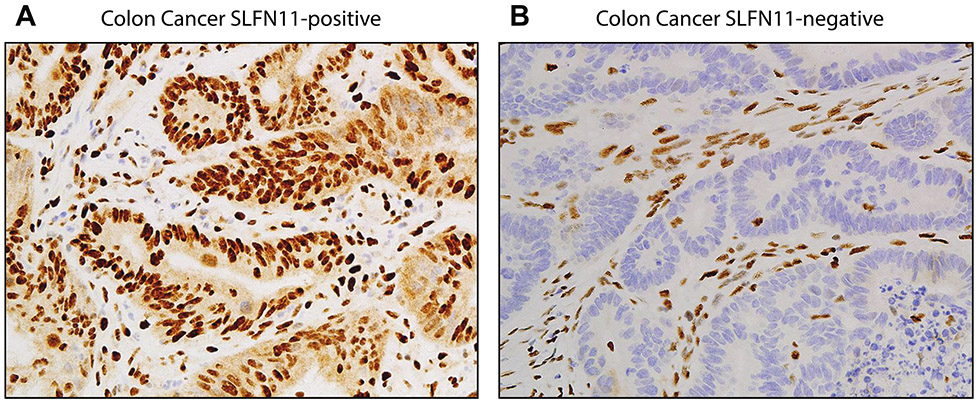

Hence, it will be important to develop methods to measure SLFN11 expression level in tumor samples. Several methods are being explored. Quantitative assessment of SLFN11 protein expression in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor samples should provide immediate clinical translational implications. Figure 6 shows our own representative examples from colon cancer patients. SLFN11 immunostaining has also been reported by others (Deng, et al., 2015; Lok, et al., 2016; Pietanza, et al., 2018). In PDX models and in retrospective analyses of clinical samples, SLFN11 detected by immunohistochemistry has proven to be a strong predictor of PARP inhibitor response and progression-free survival (Lok, et al., 2017; Pietanza, et al., 2018). SLFN11 protein expression in cancer cell lines is also highly correlated with SLFN11 transcripts (Barretina, et al., 2012; Gardner, et al., 2017; Zoppoli, et al., 2012), indicating that determining SLFN11 status by transcript measurements or RNA-seq could be used to score tumors. Also, SLFN11 promoter hypermethylation is highly correlated with lack of SLFN11 expression (Nogales, et al., 2016; Reinhold, Varma, et al., 2017). However, promoter hypermethylation is not sufficient to predict lack of SLFN11 expression as lack of SLFN11 in approximately 50% of the cancer cells is related to other epigenetic changes including chromatin acetylation and methylation (Gardner, et al., 2017; Tang, et al., 2018).

Figure 6.

Nuclear staining of SLFN11 in colon cancer patient samples. A. SLFN11-positive tumor. B. SLFN11-negative tumor. Note the nuclear staining of SLFN11 in the stroma cells of both samples. Lymphocytes generally have high SLFN11 expression. Paraffin-embedded samples were stained with SLFN11 antibody (D-2): sc-515071X (200 μg/100 μl), mouse monoclonal, Santa Cruz.

An important consideration for clinical translation is the variations in SLFN11 expression on exposure to chemotherapy and in patients that become resistant to DNA-targeting treatments. Gardner et al. found a significant decrease in SLFN11 expression in tumors progressing after chemotherapy (Gardner, et al., 2017). This suggests that SLFN11 expression on a fresh biopsy prior to starting treatment would be more relevant in determining treatment response rather than SLFN11 expression on an archival tumor. Establishment of standardized assays to score SLFN11 expression and prospective clinical studies using SLFN11 expression for patient stratification are warranted. Finally, the potential role of SLFN11 in the native immune response (Mezzadra, et al., 2019) may contribute to its value as predictive biomarker of response to immune therapies.

Acknowledgements

Our studies are supported by the Center for Cancer Research, the Intramural Program of the National Cancer Institute (Z01 BC 006161 and 006150), National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Agelopoulos K, Richter GH, Schmidt E, Dirksen U, von Heyking K, Moser B, Klein HU, Kontny U, Dugas M, Poos K, Korsching E, Buch T, Weckesser M, Schulze I, Besoke R, Witten A, Stoll M, Kohler G, Hartmann W, Wardelmann E, Rossig C, Baumhoer D, Jurgens H, Burdach S, Berdel WE, & Muller-Tidow C (2015). Deep Sequencing in Conjunction with Expression and Functional Analyses Reveals Activation of FGFR1 in Ewing Sarcoma. Clin Cancer Res, 21, 4935–4946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antony S, Agama KK, Miao ZH, Takagi K, Wright MH, Robles AI, Varticovski L, Nagarajan M, Morrell A, Cushman M, & Pommier Y (2007). Novel indenoisoquinolines NSC 725776 and NSC 724998 produce persistent topoisomerase I cleavage complexes and overcome multidrug resistance. Cancer research, 67, 10397–10405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, Wilson CJ, Lehar J, Kryukov GV, Sonkin D, Reddy A, Liu M, Murray L, Berger MF, Monahan JE, Morais P, Meltzer J, Korejwa A, Jane-Valbuena J, Mapa FA, Thibault J, Bric-Furlong E, Raman P, Shipway A, Engels IH, Cheng J, Yu GK, Yu J, Aspesi P Jr., de Silva M, Jagtap K, Jones MD, Wang L, Hatton C, Palescandolo E, Gupta S, Mahan S, Sougnez C, Onofrio RC, Liefeld T, MacConaill L, Winckler W, Reich M, Li N, Mesirov JP, Gabriel SB, Getz G, Ardlie K, Chan V, Myer VE, Weber BL, Porter J, Warmuth M, Finan P, Harris JL, Meyerson M, Golub TR, Morrissey MP, Sellers WR, Schlegel R, & Garraway LA (2012). The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature, 483, 603–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Branzei D, & Foiani M (2008). Regulation of DNA repair throughout the cell cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 9, 297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Branzei D, & Foiani M (2010). Maintaining genome stability at the replication fork. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 11, 208–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker KM, Flower D, Lopez E, Kyle S, Meuth M, Curtin NJ, & Helleday T (2005). Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature, 434, 913–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton JH, Mazcko CN, LeBlanc AK, Covey JM, Ji JJ, Kinders RJ, Parchment RE, Khanna C, Paoloni M, Lana SE, Weishaar K, London CA, Kisseberth WC, Krick E, Vail DM, Childress MO, Bryan JN, Barber LG, Ehrhart EJ, Kent MS, Fan TM, Kow KY, Northup N, Wilson-Robles H, Tomaszewski JE, Holleran JL, Muzzio M, Eiseman J, Beumer JH, Doroshow JH, & Pommier Y (2018). NCI Comparative Oncology Program Testing of Non-Camptothecin Indenoisoquinoline Topoisomerase I Inhibitors in Naturally Occurring Canine Lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chabner BA, & Roberts TG (2005). Timeline: Chemotherapy and the war on cancer. Nat Rev Cancer, 5, 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng CH, & Kuchta RD (1993). DNA polymerase epsilon: aphidicolin inhibition and the relationship between polymerase and exonuclease activity. Biochemistry, 32, 8568–8574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sørensen Claus Storgaard, B. H, Nähse-Kumpf Viola and Syljuåsen Randi G. (2011). Faithful DNA Replication Requires Regulation of CDK Activity by Checkpoint Kinases. In Seligmann DH (Ed.): InTech. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cliby WA, Roberts CJ, Cimprich KA, Stringer CM, Lamb JR, Schreiber SL, & Friend SH (1998). Overexpression of a kinase-inactive ATR protein causes sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents and defects in cell cycle checkpoints. EMBO J, 17, 159–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coleman RL, Oza AM, Lorusso D, Aghajanian C, Oaknin A, Dean A, Colombo N, Weberpals JI, Clamp A, Scambia G, Leary A, Holloway RW, Gancedo MA, Fong PC, Goh JC, O'Malley DM, Armstrong DK, Garcia-Donas J, Swisher EM, Floquet A, Konecny GE, McNeish IA, Scott CL, Cameron T, Maloney L, Isaacson J, Goble S, Grace C, Harding TC, Raponi M, Sun J, Lin KK, Giordano H, Ledermann JA, & Investigators, A. (2017). Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet, 390, 1949–1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng Y, Cai Y, Huang Y, Yang Z, Bai Y, Liu Y, Deng X, & Wang J (2015). High SLFN11 expression predicts better survival for patients with KRAS exon 2 wild type colorectal cancer after treated with adjuvant oxaliplatin-based treatment. BMC Cancer, 15, 833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dietlein F, Thelen L, & Reinhardt HC (2014). Cancer-specific defects in DNA repair pathways as targets for personalized therapeutic approaches. Trends Genet, 30, 326–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doroshow JH (1996). Anthraycyclines and anthracenediones In Chabner BA & Longo DL (Eds.), Cancer chemotherapy and biotherapy (second ed., pp. 409–434). Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, Santarosa M, Dillon KJ, Hickson I, Knights C, Martin NM, Jackson SP, Smith GC, & Ashworth A (2005). Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature, 434, 917–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedel AM, Pike BL, & Gasser SM (2009). ATR/Mec1: coordinating fork stability and repair. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 21, 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardner EE, Lok BH, Schneeberger VE, Desmeules P, Miles LA, Arnold PK, Ni A, Khodos I, de Stanchina E, Nguyen T, Sage J, Campbell JE, Ribich S, Rekhtman N, Dowlati A, Massion PP, Rudin CM, & Poirier JT (2017). Chemosensitive Relapse in Small Cell Lung Cancer Proceeds through an EZH2-SLFN11 Axis. Cancer Cell, 31, 286–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gelmon KA, Tischkowitz M, Mackay H, Swenerton K, Robidoux A, Tonkin K, Hirte H, Huntsman D, Clemons M, Gilks B, Yerushalmi R, Macpherson E, Carmichael J, & Oza A (2011). Olaparib in patients with recurrent high-grade serous or poorly differentiated ovarian carcinoma or triple-negative breast cancer: a phase 2, multicentre, open-label, non-randomised study. Lancet Oncol, 12, 852–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geserick P, Kaiser F, Klemm U, Kaufmann SH, & Zerrahn J (2004). Modulation of T cell development and activation by novel members of the Schlafen (slfn) gene family harbouring an RNA helicase-like motif. International immunology, 16, 1535–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goss KL, & Gordon DJ (2016). Gene expression signature based screening identifies ribonucleotide reductase as a candidate therapeutic target in Ewing sarcoma. Oncotarget, 7, 63003–63019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanahan D, & Weinberg RA (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell, 144, 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanzlikova H, Kalasova I, Demin AA, Pennicott LE, Cihlarova Z, & Caldecott KW (2018). The Importance of Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase as a Sensor of Unligated Okazaki Fragments during DNA Replication. Mol Cell, 71, 319–331 e313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He T, Zhang M, Zheng R, Zheng S, Linghu E, Herman JG, & Guo M (2017). Methylation of SLFN11 is a marker of poor prognosis and cisplatin resistance in colorectal cancer. Epigenomics, 9, 849–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hitchings GH, & Elion GB (1985). Layer on layer: the Bruce F. Cain memorial Award lecture. Cancer research, 45, 2415–2420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho GY, Woodward N, & Coward JI (2016). Cisplatin versus carboplatin: comparative review of therapeutic management in solid malignancies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 102, 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Josse R, Martin SE, Guha R, Ormanoglu P, Pfister TD, Reaper PM, Barnes CS, Jones J, Charlton P, Pollard JR, Morris J, Doroshow JH, & Pommier Y (2014). ATR inhibitors VE-821 and VX-970 sensitize cancer cells to topoisomerase i inhibitors by disabling DNA replication initiation and fork elongation responses. Cancer research, 74, 6968–6979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang MH, Wang J, Makena MR, Lee JS, Paz N, Hall CP, Song MM, Calderon RI, Cruz RE, Hindle A, Ko W, Fitzgerald JB, Drummond DC, Triche TJ, & Reynolds CP (2015). Activity of MM-398, nanoliposomal irinotecan (nal-IRI), in Ewing's family tumor xenografts is associated with high exposure of tumor to drug and high SLFN11 expression. Clin Cancer Res, 21, 1139–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karnitz LM, & Zou L (2015). Molecular Pathways: Targeting ATR in Cancer Therapy. Clin Cancer Res, 21, 4780–4785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelland L (2007). The resurgence of platinum-based cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer, 7, 573–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King C, Diaz HB, McNeely S, Barnard D, Dempsey J, Blosser W, Beckmann R, Barda D, & Marshall MS (2015). LY2606368 Causes Replication Catastrophe and Antitumor Effects through CHK1-Dependent Mechanisms. Molecular cancer therapeutics, 14, 2004–2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kummar S, Chen A, Gutierrez M, Pfister TD, Wang L, Redon C, Bonner WM, Yutzy W, Zhang Y, Kinders RJ, Ji J, Allen D, Covey JM, Eiseman JL, Holleran JL, Beumer JH, Rubinstein L, Collins J, Tomaszewski J, Parchment R, Pommier Y, & Doroshow JH (2016). Clinical and pharmacologic evaluation of two dosing schedules of indotecan (LMP400), a novel indenoisoquinoline, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol, 78, 73–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lecona E, & Fernandez-Capetillo O (2018). Targeting ATR in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, Friedlander M, Vergote I, Rustin G, Scott C, Meier W, Shapira-Frommer R, Safra T, Matei D, Macpherson E, Watkins C, Carmichael J, & Matulonis U (2012). Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med, 366, 1382–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li M, Kao E, Gao X, Sandig H, Limmer K, Pavon-Eternod M, Jones TE, Landry S, Pan T, Weitzman MD, & David M (2012). Codon-usage-based inhibition of HIV protein synthesis by human schlafen 11. Nature, 491, 125–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li M, Kao E, Malone D, Gao X, Wang JYJ, & David M (2018). DNA damage-induced cell death relies on SLFN11-dependent cleavage of distinct type II tRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 25, 1047–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Litton JK, Rugo HS, Ettl J, Hurvitz SA, Goncalves A, Lee KH, Fehrenbacher L, Yerushalmi R, Mina LA, Martin M, Roche H, Im YH, Quek RGW, Markova D, Tudor IC, Hannah AL, Eiermann W, & Blum JL (2018). Talazoparib in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer and a Germline BRCA Mutation. N Engl J Med, 379, 753–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lok BH, Gardner EE, Schneeberger VE, Ni A, Desmeules P, Rekhtman N, de Stanchina E, Teicher BA, Riaz N, Powell SN, Poirier JT, & Rudin CM (2016). PARP Inhibitor Activity Correlates with SLFN11 Expression and Demonstrates Synergy with Temozolomide in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lok BH, Gardner EE, Schneeberger VE, Ni A, Desmeules P, Rekhtman N, de Stanchina E, Teicher BA, Riaz N, Powell SN, Poirier JT, & Rudin CM (2017). PARP Inhibitor Activity Correlates with SLFN11 Expression and Demonstrates Synergy with Temozolomide in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 23, 523–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Long BH, & Stringfellow DA (1988). Inhibitors of topoisomerase II: structure-activity relationships and mechanism of action of podophyllin congeners. Adv. Enzyme. Regul, 27, 223–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lord CJ, & Ashworth A (2017). PARP inhibitors: Synthetic lethality in the clinic. Science, 355, 1152–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lord CJ, Tutt AN, & Ashworth A (2015). Synthetic lethality and cancer therapy: lessons learned from the development of PARP inhibitors. Annu Rev Med, 66, 455–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marechal A, Li JM, Ji XY, Wu CS, Yazinski SA, Nguyen HD, Liu S, Jimenez AE, Jin J, & Zou L (2014). PRP19 transforms into a sensor of RPA-ssDNA after DNA damage and drives ATR activation via a ubiquitin-mediated circuitry. Mol Cell, 53, 235–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mavrommatis E, Fish EN, & Platanias LC (2013). The schlafen family of proteins and their regulation by interferons. J Interferon Cytokine Res, 33, 206–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mezzadra R, de Bruijn M, Jae LT, Gomez-Eerland R, Duursma A, Scheeren FA, Brummelkamp TR, & Schumacher TN (2019). SLFN11 can sensitize tumor cells towards IFN-gamma-mediated T cell killing. PLoS One, 14, e0212053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, Oza AM, Mahner S, Redondo A, Fabbro M, Ledermann JA, Lorusso D, Vergote I, Ben-Baruch NE, Marth C, Madry R, Christensen RD, Berek JS, Dorum A, Tinker AV, du Bois A, Gonzalez-Martin A, Follana P, Benigno B, Rosenberg P, Gilbert L, Rimel BJ, Buscema J, Balser JP, Agarwal S, Matulonis UA, & Investigators E-ON (2016a). Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive, Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med, 375, 2154–2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, Oza AM, Mahner S, Redondo A, Fabbro M, Ledermann JA, Lorusso D, Vergote I, Ben-Baruch NE, Marth C, Madry R, Christensen RD, Berek JS, Dorum A, Tinker AV, du Bois A, Gonzalez-Martin A, Follana P, Benigno B, Rosenberg P, Gilbert L, Rimel BJ, Buscema J, Balser JP, Agarwal S, Matulonis UA, & Investigators E-ON (2016b). Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive, Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 375, 2154–2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moldovan GL, & D'Andrea AD (2009). How the fanconi anemia pathway guards the genome. Annu Rev Genet, 43, 223–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mu Y, Lou J, Srivastava M, Zhao B, Feng XH, Liu T, Chen J, & Huang J (2016). SLFN11 inhibits checkpoint maintenance and homologous recombination repair. EMBO Rep, 17, 94–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murai J (2017). Targeting DNA repair and replication stress in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Int J Clin Oncol, 22, 619–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murai J, Feng Y, Yu GK, Ru Y, Tang SW, Shen Y, & Pommier Y (2016). Resistance to PARP inhibitors by SLFN11 inactivation can be overcome by ATR inhibition. Oncotarget, 7, 76534–76550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murai J, Huang SY, Das BB, Renaud A, Zhang Y, Doroshow JH, Ji J, Takeda S, & Pommier Y (2012). Trapping of PARP1 and PARP2 by Clinical PARP Inhibitors. Cancer research, 72, 5588–5599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murai J, Huang SY, Renaud A, Zhang Y, Ji J, Takeda S, Morris J, Teicher B, Doroshow JH, & Pommier Y (2014). Stereospecific PARP trapping by BMN 673 and comparison with olaparib and rucaparib. Molecular cancer therapeutics, 13, 433–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murai J, & Pommier Y (2015). Classification of PARP inhibitors based on PAPR trapping and catalytic inhibition, and rationale for combination with topoisomerase I inhibitors and alkylating agents In Sharma N. J. C. a. R. A. (Ed.), PARP inhibitors for Cancer Therapy (Vol. 83). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murai J, & Pommier Y (2019). PARP Trapping Beyond Homologous Recombination and Platinum Sensitivity in Cancers. Annual Review of Cancer Biology, Vol 3, 3, 131–150. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murai J, Tang SW, Leo E, Baechler SA, Redon CE, Zhang H, Al Abo M, Rajapakse VN, Nakamura E, Jenkins LMM, Aladjem MI, & Pommier Y (2018). SLFN11 Blocks Stressed Replication Forks Independently of ATR. Mol Cell, 69, 371–384 e376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nam EA, & Cortez D (2011). ATR signalling: more than meeting at the fork. Biochem J, 436, 527–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nitiss JL (2009). Targeting DNA topoisomerase II in cancer chemotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer, 9, 338–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nogales V, Reinhold WC, Varma S, Martinez-Cardus A, Moutinho C, Moran S, Heyn H, Sebio A, Barnadas A, Pommier Y, & Esteller M (2016). Epigenetic inactivation of the putative DNA/RNA helicase SLFN11 in human cancer confers resistance to platinum drugs. Oncotarget, 7, 3084–3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nordlund P, & Reichard P (2006). Ribonucleotide reductases. Annu Rev Biochem, 75, 681–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O'Connor MJ (2015). Targeting the DNA Damage Response in Cancer. Mol Cell, 60, 547–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paull KD, Shoemaker RH, Hodes L, Monks A, Scudiero DA, Rubinstein L, Plowman J, & Boyd M (1989). Display and analysis of patterns of differential activity of drugs against human tumor cell lines: development of a mean graph and COMPARE algorithm. J. Natl. Cancer Inst, 81, 1088–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pietanza MC, Waqar SN, Krug LM, Dowlati A, Hann CL, Chiappori A, Owonikoko TK, Woo KM, Cardnell RJ, Fujimoto J, Long L, Diao L, Wang J, Bensman Y, Hurtado B, de Groot P, Sulman EP, Wistuba II, Chen A, Fleisher M, Heymach JV, Kris MG, Rudin CM, & Byers LA (2018). Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase II Study of Temozolomide in Combination With Either Veliparib or Placebo in Patients With Relapsed-Sensitive or Refractory Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol, 36, 2386–2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Polley E, Kunkel M, Evans D, Silvers T, Delosh R, Laudeman J, Ogle C, Reinhart R, Selby M, Connelly J, Harris E, Fer N, Sonkin D, Kaur G, Monks A, Malik S, Morris J, & Teicher BA (2016). Small Cell Lung Cancer Screen of Oncology Drugs, Investigational Agents, and Gene and microRNA Expression. J Natl Cancer Inst, 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pommier Y (2013). Drugging topoisomerases: lessons and challenges. ACS chemical biology, 8, 82–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pommier Y, & Cushman M (2009). The indenoisoquinoline noncamptothecin topoisomerase I inhibitors: update and perspectives. Molecular cancer therapeutics, 8, 1008–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pommier Y, Leo E, Zhang H, & Marchand C (2010). DNA topoisomerases and their poisoning by anticancer and antibacterial drugs. Chemistry & biology, 17, 421–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pommier Y, O'Connor MJ, & de Bono J (2016). Laying a trap to kill cancer cells: PARP inhibitors and their mechanisms of action. Sci Transl Med, 8, 362ps317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pommier Y, Sun Y, Huang SN, & Nitiss JL (2016). Roles of eukaryotic topoisomerases in transcription, replication and genomic stability. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 17, 703–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rajapakse VN, Luna A, Yamade M, Loman L, Varma S, Sunshine M, Iorio F, Sousa FG, Elloumi F, Aladjem MI, Thomas A, Sander C, Kohn KW, Benes CH, Garnett M, Reinhold WC, & Pommier Y (2018). CellMinerCDB for Integrative Cross-Database Genomics and Pharmacogenomics Analyses of Cancer Cell Lines. iScience, 10, 247–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reinhold WC, Sunshine M, Varma S, Doroshow JH, & Pommier Y (2015). Using CellMiner 1.6 for Systems Pharmacology and Genomic Analysis of the NCI-60. Clin Cancer Res, 21, 3841–3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reinhold WC, Thomas A, & Pommier Y (2017). DNA-Targeted Precision Medicine; Have We Been Caught Sleeping? Trends in Cancer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reinhold WC, Varma S, Sunshine M, Rajapakse V, Luna A, Kohn KW, Stevenson H, Wang Y, Heyn H, Nogales V, Moran S, Goldstein DJ, Doroshow JH, Meltzer PS, Esteller M, & Pommier Y (2017). The NCI-60 Methylome and Its Integration into CellMiner. Cancer research, 77, 601–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Robson M, Im SA, Senkus E, Xu BH, Domchek SM, Masuda N, Delaloge S, Li W, Tung N, Armstrong A, Wu WT, Goessl C, Runswick S, & Conte P (2017). Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer in Patients with a Germline BRCA Mutation. New England Journal of Medicine, 377, 523–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ross W, Rowe T, Glisson B, Yalowich J, & Liu L (1984). Role of topoisomerase II in mediating epipodophyllotoxin-induced DNA cleavage. Cancer research, 44, 5857–5860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Scherf U, Ross DT, Waltham M, Smith LH, Lee JK, Tanabe L, Kohn KW, Reinhold WC, Myers TG, Andrews DT, Scudiero DA, Eisen MB, Sausville EA, Pommier Y, Botstein D, Brown PO, & Weinstein JN (2000). A gene expression database for the molecular pharmacology of cancer. Nat Genet, 24, 236–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schwarz DA, Katayama CD, & Hedrick SM (1998). Schlafen, a new family of growth regulatory genes that affect thymocyte development. Immunity, 9, 657–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Seiler JA, Conti C, Syed A, Aladjem MI, & Pommier Y (2007). The Intra-S-Phase Checkpoint Affects both DNA Replication Initiation and Elongation: Single-Cell and -DNA Fiber Analyses. Mol Cell Biol, 27, 5806–5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shen Y, Rehman FL, Feng Y, Boshuizen J, Bajrami I, Elliott R, Wang B, Lord CJ, Post LE, & Ashworth A (2013). BMN 673, a novel and highly potent PARP1/2 inhibitor for the treatment of human cancers with DNA repair deficiency. Clin Cancer Res, 19, 5003–5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sousa FG, Matuo R, Tang SW, Rajapakse VN, Luna A, Sander C, Varma S, Simon PH, Doroshow JH, Reinhold WC, & Pommier Y (2015). Alterations of DNA repair genes in the NCI-60 cell lines and their predictive value for anticancer drug activity. DNA Repair (Amst), 28, 107–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stewart CA, Tong P, Cardnell RJ, Sen T, Li LR, Gay CM, Masrorpour F, Fan Y, Bara RO, Feng Y, Ru YB, Fujimoto J, Kundu ST, Post LE, Yu KR, Shen YQ, Glisson BS, Wistuba I, Heymach JV, Gibbons DL, Wang J, & Byers LA (2017). Dynamic variations in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), ATM, and SLFN11 govern response to PARP inhibitors and cisplatin in small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget, 8, 28575–28587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Strumberg D, Pilon AA, Smith M, Hickey R, Malkas L, & Pommier Y (2000). Conversion of topoisomerase I cleavage complexes on the leading strand of ribosomal DNA into 5'-phosphorylated DNA double-strand breaks by replication runoff. Mol. Cell. Biol, 20, 3977–3987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Syljuasen RG, Sorensen CS, Hansen LT, Fugger K, Lundin C, Johansson F, Helleday T, Sehested M, Lukas J, & Bartek J (2005). Inhibition of human Chk1 causes increased initiation of DNA replication, phosphorylation of ATR targets, and DNA breakage. Mol Cell Biol, 25, 3553–3562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tang SW, Bilke S, Cao L, Murai J, Sousa FG, Yamade M, Rajapakse V, Varma S, Helman LJ, Khan J, Meltzer PS, & Pommier Y (2015). SLFN11 Is a Transcriptional Target of EWS-FLI1 and a Determinant of Drug Response in Ewing Sarcoma. Clin Cancer Res, 21, 4184–4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tang SW, Thomas A, Murai J, Trepel JB, Bates SE, Rajapakse VN, & Pommier Y (2018). Overcoming Resistance to DNA-Targeted Agents by Epigenetic Activation of Schlafen 11 (SLFN11) Expression with Class I Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res, 24, 1944–1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tian L, Song S, Liu X, Wang Y, Xu X, Hu Y, & Xu J (2014). Schlafen-11 sensitizes colorectal carcinoma cells to irinotecan. Anticancer Drugs, 25, 1175–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, Domchek SM, Audeh MW, Weitzel JN, Friedlander M, Arun B, Loman N, Schmutzler RK, Wardley A, Mitchell G, Earl H, Wickens M, & Carmichael J (2010). Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet, 376, 235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vesela E, Chroma K, Turi Z, & Mistrik M (2017). Common Chemical Inductors of Replication Stress: Focus on Cell-Based Studies. Biomolecules, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang JY, Deng XY, Li YS, Ma XC, Feng JX, Yu B, Chen Y, Luo YL, Wang X, Chen ML, Fang ZX, Zheng FX, Li YP, Zhong Q, Kang TB, Song LB, Xu RH, Zeng MS, Chen W, Zhang H, Xie W, & Gao S (2018). Structure of Schlafen13 reveals a new class of tRNA/rRNA- targeting RNase engaged in translational control. Nat Commun, 9, 1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zeeberg BR, Reinhold W, Snajder R, Thallinger GG, Weinstein JN, Kohn KW, & Pommier Y (2012). Functional categories associated with clusters of genes that are co-expressed across the NCI-60 cancer cell lines. PLoS One, 7, e30317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zeman MK, & Cimprich KA (2014). Causes and consequences of replication stress. Nat Cell Biol, 16, 2–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zimmermann M, Murina O, Reijns MAM, Agathanggelou A, Challis R, Tarnauskaite Z, Muir M, Fluteau A, Aregger M, McEwan A, Yuan W, Clarke M, Lambros MB, Paneesha S, Moss P, Chandrashekhar M, Angers S, Moffat J, Brunton VG, Hart T, de Bono J, Stankovic T, Jackson AP, & Durocher D (2018). CRISPR screens identify genomic ribonucleotides as a source of PARP-trapping lesions. Nature. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zoppoli G, Regairaz M, Leo E, Reinhold WC, Varma S, Ballestrero A, Doroshow JH, & Pommier Y (2012). Putative DNA/RNA helicase Schlafen-11 (SLFN11) sensitizes cancer cells to DNA-damaging agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 109, 15030–15035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]