Abstract

Background

The growth of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has been increasing, including amongst psychological clients. Therefore, it is important to investigate psychologists’ attitudes towards CAM. Negative attitudes towards CAM among psychologists could be a barrier to CAM integration into psychological services and may prevent clients to trust psychologists. This study aims to compare Indonesian and Australian psychologists’ attitudes towards CAM using the previously published study on Psychologists’ Attitudes Towards Complementary and Alternative Therapies (PATCAT) scale validation.

Methods

The PATCAT scale was adapted from an Australian study to an Indonesian version using backward-and-forward translation. This scale was used to investigate attitudes towards: (1) CAM knowledge; (2) CAM integration; and (3) the risks associated with CAM. An online survey was sent to all Indonesian psychologists and completed by 247 participants. Afterward, the data were compared with the published data from 115 Australian psychologists.

Results

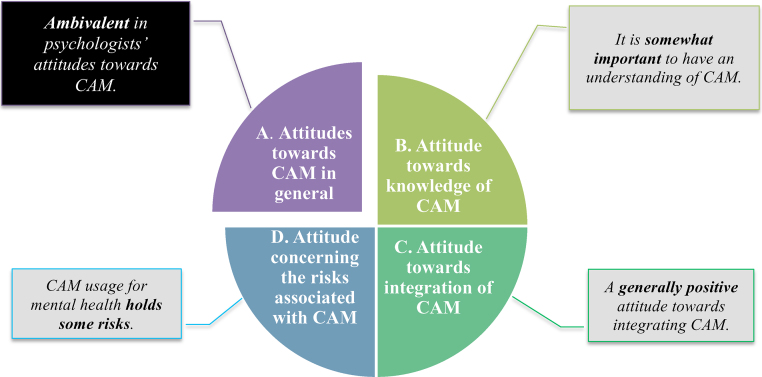

In general, psychologists in Indonesia and Australia showed relatively similar ambivalent attitudes towards CAM. This uncertainty may stem from the same Western psychology education, which is a basis for the medical models in both nations. They also considered it somewhat important to have an understanding of CAM. Participants in both nations displayed positive attitude towards CAM integration into psychological services. However, they felt that CAM usage for mental health holds some risks.

Conclusion

Australian and Indonesian psychologists reported ambivalent attitudes towards CAM that might be reduced with clear regulation of CAM integration into psychological services from the government and professional organizations.

Keywords: Attitude, Complementary and alternative medicine, Cross culture, Cultural psychology, Clinical psychologist

1. Introduction

The use of complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) is increasing internationally, including amongst people with psychological issues (e.g., anxiety and depression).1, 2, 3 Therefore, evaluating psychologists’ attitudes towards CAM is important in designing psychology educational curricula, planning clinical practice standards, and formulating health policies or regulations.4, 5 Negative or skeptical attitudes towards CAM among psychologists could be a barrier to CAM integration into mental health services.1, 4 It may also prevent clients to trust psychologists by not disclosing if they have used CAM.6

Only few studies have investigated psychologists’ attitudes towards CAM, most of which have been conducted in Australia. Qualitative studies among provisional and full-registered Australian psychologists found that participants showed mixed-attitudes towards CAM where they were interested but also cautious about CAM integration into psychological services.1, 7 Findings from quantitative studies using the Psychologists’ Attitudes Towards Complementary and Alternative Therapies (PATCAT) scale showed relatively similar results. A survey to validate PATCAT found that full-registered Australian psychologists generally accepted the integration of CAM in psychological services but focused more on the importance of rigorous scientific testing compared with psychology students.3 A relatively new survey also found that Australian professional psychologists (who predominantly work in clinical settings) and academic psychologists (who predominantly working in academia) reported their favourableness in integrating CAM into conventional psychotherapy as well as emphasized the associated risks of using CAM in clinical practice.8

The PATCAT scale has also been used in international survey to investigate the use of CAM among psychologists in Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand.4 This cross-national survey concluded that attitudes toward CAM and level of training in CAM could predict the use of CAM among psychologists. To the best of the author's knowledge, there are no studies to compare psychologists’ attitudes towards CAM in Eastern and Western nations, which might be dissimilar because of variances in socio-cultural background. For example, a cross-sectional survey found that Indonesian health-care providers (HCPs) showed more positive attitudes about CAM treatment in cases of childhood cancer because of their more holistic approach (body, mind, and spirit connections) compared with Dutch HCPs.9

The terms “traditional”, “complementary”, and “alternative” medicine were used interchangeably in Indonesia and understood varyingly because it has been part of Indonesian culture for years10, 11; similar with other Eastern nations (e.g., Korea and China) who perceive traditional medicine and CAM as part of their cultural heritage.12 However, the Indonesian Ministry of Health defined CAM as, “A non-conventional treatment aimed to improve public health status involving promotive, preventive, curative, and rehabilitative ways and it is obtained through a structured education with quality, safety, and high effectiveness that are based on biomedical science and have not been accepted in conventional medicine.”13 This Indonesian CAM definition shares some similarities with the definition of CAM used in the PATCAT scale validation among Australian psychologists, “CAM is a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine.”3 Moreover, this CAM definition was adopted from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (formerly National Centre for Complementary and Alternative Medicines), the United States.

Interestingly, psychology curricula in Australia and Southeast Asian nations, including Indonesia, intensively refer to Euro-American psychology education.14 In both nations, an individual who wants to become a psychologist must complete six years of education that consist of an undergraduate degree in psychology, a master of professional psychology program, and a professional internship.1, 15 However, Asian psychologists reported that the Western conventional psychotherapy, which they learnt at university, may not always be culturally appropriate to be applied to their clients because of the different perspectives and approaches related to mental illness between the two cultures.14, 16 Therefore, this current study aimed to fill the gap by comparing Indonesian psychologists’ attitudes towards CAM with Australian psychologists using the previously published PATCAT study results.3 However, this short report will not discuss the prevalence and use of CAM, or CAM efficacy and effectiveness since there is an abundance of references on these issues and they are beyond the scope of the current study.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure and participants

This current study in Indonesia has been complied in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the School of Psychology at the University of Queensland (#16-PSYCH-PHD-08-JH). An anonymous online survey was distributed to all psychologists across Indonesia. A link to the online survey, information sheet, and consent form were sent in an email to 1015 members of the Indonesian Clinical Psychology Association. To compare Indonesian psychologists’ attitudes towards CAM with psychologists in Australia, the data from the PATCAT validation among Australian psychologists was used.3 In this Australian study, the survey and a reply paid envelope were posted to nearly 250 psychologists in clinics, hospitals, and university counselling services.

2.2. Instrument

The PATCAT scale from the Australian study3 was adapted to an Indonesian version using backward-and-forward translation. The details of this adaptation process have been reported elsewhere.15, 17 The PATCAT scale contained ten items distributed into three sub-scales: (1) attitude towards knowledge of CAM; (2) attitude towards integration of CAM; and (3) attitude concerning the risks associated with CAM, which were assessed through a 7-point Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) with higher scores reflecting more positive attitudes towards CAM. The Cronbach coefficient alpha for overall PATCAT was .87 in the Indonesian survey and .84 in the Australian survey.3

2.3. Analysis

Data from psychologists in Indonesia were checked manually for missing values and analysed using SPSS software (v22) for statistical analysis. Incomplete data (missing values) were checked using Missing Value Analysis (MVA) and removed from the final analysis using the most appropriate approach. Normality assumptions were checked using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, histograms, and Q–Q plot. Thereafter, data from this Indonesian survey were compared visually with the previous Australian survey using PATCAT3 by displaying the sub-scales and central tendency information (mean and standard deviation; median and interquartile range) in a table. Inferential statistical analysis was not used in comparing the data from these two groups because of the differences in CAM definition, participant selection process, and survey distribution between the studies.

3. Results

In total, 318 of 1015 Indonesian psychologists participated in the national online survey. The MVA found that 71 participants incompletely filled out the online survey where the values were missing completely at random. Therefore, the data were removed using the listwise deletion approach, leaving a final Indonesian sample of N = 247. On the other hand, the Australian study3 conducted an analysis from 115 psychologists who were predominantly female (72%), which was parallel with the Indonesian sample in which 85% of the psychologists were female. In addition, participants from both nations were dominated by the same age group of 26–35 years old.

A Kolmogorov–Smirnov test indicated that attitudes towards CAM among Indonesian psychologists were not distributed normally, D(247) = .19, p < .001. A series of Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests also showed non-normal distribution for each sub-scale: (1) attitude towards knowledge of CAM, D(247) = .22, p < .001; (2) attitude towards integration of CAM, D(247) = .21, p < .001; and (3) attitude concerning the risks associated with CAM, D(247) = .23, p < .001. Therefore, median and interquartile ranges are presented to supplement the mean and standard deviation of Indonesian psychologists’ PATCAT scale results. In contrast, data from the Australian survey3 were normally distributed. The visual comparison of PATCAT scale central tendency information between psychologists in Indonesia and Australia is provided in Table 1 and Fig. 1, including the interpretation of the scale.

Table 1.

Comparison of Attitudes Towards CAM Among Psychologists in Australia and Indonesia

| Psychologists’ Attitudes Towards Complementary and Alternative Therapies (PATCAT) Scale | Australia# (N = 115) | Indonesia (N = 247) |

PATCAT scale interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-scale and item | (M; SD) | (M; SD) | (Med; IQR) | |

| A. Attitudes towards CAM in general | 4.58 (0.91) | 4.67 (0.79) | 4.70 (0.60) | A higher score indicates greater positive attitudes and lower scores indicate negative attitudes towards CAM. |

| B. Attitude towards knowledge of CAM | 4.36 (1.23) | 4.70 (1.12) | 4.67 (1.00) | A higher score indicates greater appreciation and lower scores indicate disinterest on CAM knowledge. |

| 1. Psychology professionals should be able to advise their clients about commonly used complementary therapy methods. | 4.56 (1.35) | 4.24 (1.31) | 4.00 (1.00) | |

| 2. Information about complementary therapy practices should be included in my psychology degree curriculum. | 4.09 (1.51) | 4.82 (1.32) | 5.00 (1.00) | |

| 3. Knowledge about complementary therapies is important to me as a practicing clinical psychologist. | 4.43 (1.51) | 5.05 (1.21) | 5.00 (1.00) | |

| C. Attitude towards integration of CAM | 5.33 (0.92) | 4.94 (1.10) | 5.00 (0.67) | A higher score indicates greater favorableness on integrating CAM and lower scores indicate lesser positive attitude. |

| 4. Clinical care should integrate the best of conventional and complementary practices. | 5.61 (1.15) | 4.84 (1.21) | 5.00 (1.00) | |

| 5. Complementary therapies include ideas and methods from which conventional psychotherapy could benefit. | 5.37 (1.17) | 4.92 (1.13) | 5.00 (0.00) | |

| 6. A number of complementary and alternative approaches hold promise for the treatment of psychological conditions. | 5.01 (1.10) | 5.06 (1.19) | 5.00 (1.00) | |

| D. Attitude concerning the risks associated with CAM | 4.18 (1.02) | 4.43 (0.73) | 4.50 (0.75) | A higher score indicates greater perceived risk and lower scores indicate a positive attitude (low risk associated with CAM). |

| 7. Complementary therapies should be subject to more scientific testing before they can be accepted by psychologists. | 5.21 (1.49) | 2.11 (1.00) | 2.00 (1.00) | |

| 8. Complementary therapies can be dangerous in that they may prevent people getting proper treatment. | 4.37 (1.43) | 4.78 (1.24) | 5.00 (1.00) | |

| 9. Complementary therapy represents a confused and ill-defined approach. | 3.36 (1.42) | 5.05 (1.11) | 5.00 (1.00) | |

| 10. Complementary medicine is a threat to public health. | 2.34 (1.15) | 5.80 (0.98) | 6.00 (0.00) | |

Note. Score was from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree); #From previous study3; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; Med = median; IQR = interquartile range.

Fig. 1.

Attitudes towards CAM of psychologists in Australia and Indonesia.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to compare the attitudes towards CAM between psychologists in Indonesia and Australia using published data from previous Psychologists’ Attitudes Towards Complementary and Alternative Therapies (PATCAT) scale validation among Australian psychologists. In general, psychologists in Indonesia and Australia showed an ambivalent attitude towards CAM. This similarity of feeling may be rooted in the same Western psychology education in Indonesian and Australian universities, which is grounded in the medical model.4, 14 This uncertainty towards CAM was also found in a more recent survey using PATCAT among professional psychologists (psychological professionals who predominantly work in clinical settings) and academic psychologists (psychological professionals who predominantly work in academia) in Australia.8

In addition, lack of or unclear CAM regulations and procedures may also contribute to Australian and Indonesian psychologists’ hesitation towards CAM. A qualitative study to explore Australian psychologists’ beliefs about CAM integration into psychological practice found that they would be willing to integrate CAM if the regulatory bodies had made clear regulations or standards for this integration.7 Meanwhile, in Indonesia CAM integration into conventional health services has been regulated.13 However, this regulation emphasizes the dominant role of physicians and does not regulate the role of psychologists.6 A qualitative study with Indonesian psychologists also discovered that regulations, both from the government and professional organizations, are strongly needed if psychologists want to integrate CAM into their practices.16

Psychologists in Indonesia and Australia perceived that having CAM knowledge and understanding was fairly important. This finding is parallel with an international comparative study among psychologists in Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand, which concluded that CAM effectiveness in treating mental problems may need to be included in psychological courses.4 From the qualitative study with Australian psychologists,7 it was found that participants were interested in gaining knowledge of CAM. However, within their busy schedules of professional practice and development, they felt hesitant to familiarize themselves with another field of knowledge.3 A similar situation was found with psychologists in Indonesia. It was difficult for them to take part in CAM seminars or workshops due to their workload and financial limitations.16

Despite the challenges in gaining CAM knowledge and understanding, psychologists in Indonesia and Australia indicated a generally positive attitude towards CAM integration into psychological services. They agreed that some CAM treatments may be beneficial if combined with conventional psychotherapy. The rising trend of integrative medicine in conventional health education and services might affect psychologists’ attitude towards CAM integration.5, 9 Moreover, parts of several CAM treatments (i.e., acupuncture) were already covered by insurance in Australia, indicating that health philosophy had already shifted to be more integrative in certain areas of healthcare.18 Psychologists may also learn from their colleagues who already integrate CAM into their practices (i.e., hypnobirthing conducted by obstetricians).16 In addition, participants – as health professionals – may feel the need to respect their clients if the clients choose CAM treatments over conventional psychotherapy or combine them together.1, 6

However, participants in both nations perceived that CAM usage for mental health holds some risks. Interestingly, psychologists in Australia put more emphasis on providing rigorous scientific testing for CAM treatments before they can be accepted by psychologists (item 7) compared with Indonesian psychologists. This finding may be explained by the history of clinical psychology education in Australia, which was well-established decades before psychological education in Indonesia. This clinical psychology education is also strongly rooted in Western medical education, which highly emphasizes evidence-based medicine principles.5, 14 Additionally, the disagreement of Indonesian psychologists on CAM scientific testing might be because CAM is perceived as part of their socio-cultural heritage like in other Eastern nations.10, 11, 12 For example, jamu (Indonesian traditional herbal medicine) has been consumed for a long period of time by Indonesian people to maintain their physical fitness and to treat diseases.11, 19 Jamu, which was originally sold fresh and prepared from plant materials, is now manufactured and can be found in supermarkets.10

In opposition to this, psychologists in Indonesia showed stronger agreement to the statement that CAM is a threat to public health (item 10) than Australian psychologists. This seeming contradiction may be a result of the different CAM definitions used in the Indonesian and Australian studies. Although the definitions used in the two studies shared the similarity that CAM, in brief, has not been accepted/considered to be part of conventional medicine, participants in Indonesia and Australia may interpret CAM and its types differently. As “CAM” and “traditional medicine” are used interchangeably in Indonesian society,10 Indonesian psychologists might think about CAM treatments that overlap with traditional medicine. For example, a qualitative study among Indonesian psychologists found that some spiritual healing methods may be against their religious and personal values.6 A similar finding was found in a comparative study between Indonesian and Dutch health-care providers (HCPs).9 Indonesian HCPs in this study discouraged their cancer clients from using spiritual healing by a shaman but not religious therapy led by a religious leader; a finding that was not found among Dutch HCPs. Additionally, psychologists’ negative experiences of CAM usage may also influence their attitudes in perceiving CAM as a public health threat as predicted in a more recent survey among professional and academic psychologists in Australia8 and interviews with Indonesian psychologists.6

One limitation of this study was the different definitions of CAM used between participants in Indonesia and Australia. Future studies may use a more comprehensive definition of CAM from the World Health Organization, “A broad set of health care practices that are not part of that country's own tradition or conventional medicine and are not fully integrated into the dominant health-care system. They are used interchangeably with traditional medicine in some countries.”20 A second limitation was the different survey procedures and number of participants among the two studies. Thirdly, the non-normal distribution of the Indonesian results restrained this study from making statistical comparisons with the Australian survey results. Despite these limitations, data from participants in Indonesia and Australia were both collected using the same valid-and-reliable PATCAT scale. The demography (sex ratio and age) of psychologists in Indonesia and Australia was also relatively similar. For future studies, it would be interesting to use the PATCAT scale in comparing attitudes towards CAM among psychologists from Southeast Asia and Australia, because of the similarity of psychology curricula in these nations.

In conclusion, the current study found that psychologists in Indonesia and Australia, in general, were ambivalent in their attitudes towards CAM, which may be rooted in the same Western psychology education. Regulation of CAM integration into psychological services from government and professional organizations may enhance positive attitudes towards CAM among psychologists. Participants in the two nations also agreed that it is somewhat important to have an understanding of CAM and showed favourableness towards integrating CAM. However, they also felt that CAM usage for mental health holds some risks. Interestingly, this study found that socio-cultural factors may influence how Indonesian and Australian psychologists perceive CAM as subject to rigorous testing and as a threat to public health from a different perspective.

Conflict of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

None.

Ethical statement

This study has been approved by the School of Psychology at the University of Queensland (#16-PSYCH-PHD-08-JH).

Data availability

The questionnaire is available from the author on request. The Indonesian data for this study is part of national survey among clinical psychologists (CP) in Indonesia. Data will be made available on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The author is supported by Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education Scholarship (LPDP RI) under a doctoral degree scholarship (20150122082410). The author thanks Stephanie Pearson and Bryanna Wilson for the proofreading of the manuscript draft.

References

- 1.Hamilton K., Marietti V. A qualitative investigation of Australian psychologists’ perceptions about complementary and alternative medicine for use in clinical practice. Complem Therap Clin Pract. 2017;29:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pilkington K. Current research on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in the treatment of depression: evidence-based review. In: YK K., editor. Understanding depression. Springer; 2018. pp. 311–322. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson L.A.M., White K.M., Obst P. An examination of the psychologists’ attitudes towards complementary and alternative therapies scale within a practitioner sample. Aust Psychol. 2011;46:237–244. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stapleton P., Chatwin H., Boucher E., Crebbin S., Scott S., Smith D. Use of complementary therapies by registered psychologists: an international study. Profess Psychol: Res Pract. 2015;46:190–196. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Templeman K., Robinson A., McKenna L. Integrating complementary medicine literacy education into Australian medical curricula: student-identified techniques and strategies for implementation. Complem Therap Clin Pract. 2015;21:238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liem A., Beliefs attitudes towards, and experiences of using complementary and alternative medicine: a qualitative study of clinical psychologists in Indonesia. Eur J Integr Med. 2019;26:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson L.A.M., White K.M. Integrating complementary and alternative therapies into psychological practice: a qualitative analysis. Aust J Psychol. 2011;63:232–242. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ligorio D.V., Lyons G.C.B. Exploring differences in psychological professionals’ attitudes towards and experiences of complementary therapies in clinical practice. Aust Psychol. 2018:1–12. online first. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunawan S., Arnoldussen M., Gordijn M.S., Sitaresmi M.N., Van De Ven P.M., Ten Broeke C.A.M. Comparing health-care providers’ perspectives on complementary and alternative medicine in childhood cancer between Netherlands and Indonesia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:118–123. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liem A., Rahmawati K.D. The meaning of complementary, alternative and traditional medicine among the Indonesian psychology community: a pilot study. J Integr Med. 2017;15:288–294. doi: 10.1016/S2095-4964(17)60336-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pengpid S., Peltzer K. Utilization of traditional and complementary medicine in Indonesia: results of a national survey in 2014–15. Complem Therap Clin Pract. 2018;33:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee H.-J., Chae H., Lim Y.-K., Kwon Y.-K. Attitudes of Korean and Chinese traditional medical doctors on education of East Asian traditional medicine. Integr Med Res. 2016;5:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kementerian Kesehatan R.I. 2007. Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Nomor 1109/MENKES/PER/IX/2007 tentang penyelenggaraan pengobatan komplementer-alternatif di fasilitas pelayanan kesehatan. Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geerlings L.R., Thompson C.L., Lundberg A. Psychology and culture: exploring clinical psychology in Australia and the Malay Archipelago. J Trop Psychol. 2014;4:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liem A., Newcombe P.A. Indonesian provisional clinical psychologists’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours towards complementary-alternative medicine (CAM) Complem Therap Clin Pract. 2017;28:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liem A. “I’ve only just heard about it”: complementary and alternative medicine knowledge and educational needs of clinical psychologists in Indonesia. Medicina. 2019;55:1–14. doi: 10.3390/medicina55070333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liem A., Newcombe P.A., Pohlman A. Evaluation of complementary-alternative medicine (CAM) questionnaire development for Indonesian clinical psychologists: a pilot study. Complem Therap Med. 2017;33:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Templeman K., Robinson A. Integrative medicine models in contemporary primary health care. Complem Therap Med. 2011;19:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elfahmi, Woerdenbag H.J., Kayser O. Jamu: Indonesian traditional herbal medicine towards rational phytopharmacological use. J Herbal Med. 2014;4:51–73. [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO . 2013. WHO traditional medicine strategy 2014–2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/traditional/trm_strategy14_23/en/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The questionnaire is available from the author on request. The Indonesian data for this study is part of national survey among clinical psychologists (CP) in Indonesia. Data will be made available on reasonable request.