Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: non-specific chronic neck pain, physical therapy, randomized controlled trial, study protocol, thread embedding acupuncture

Abstract

Background:

As the number of patients who suffer from non-specific chronic neck pain (CNP) is increasing in the Republic of Korea, conservative treatments for patients with CNP have been spotlighted. Although several studies on thread embedding acupuncture (TEA) treatment have been published for the treatment of such patients, no randomized controlled trial has been reported that investigates the effectiveness and safety of the TEA treatment compared with other conservative treatments for the treatment of patients with CNP. Therefore, the purpose of this trial is to compare the effectiveness and safety of TEA to those of physical therapy (PT) for the treatment of patients with CNP.

Methods/design:

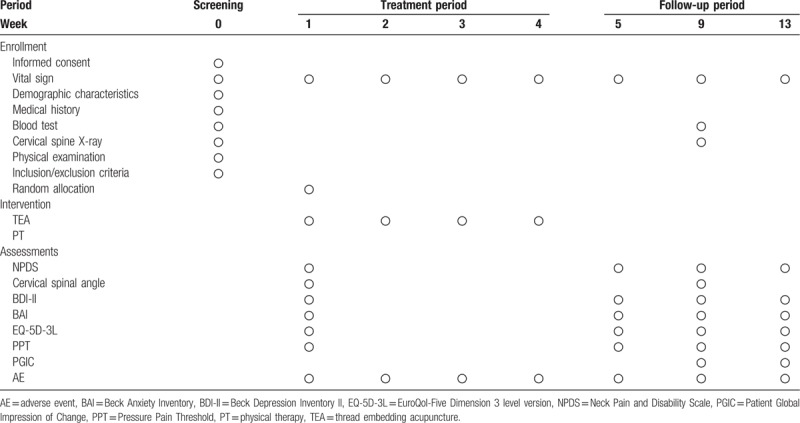

This study is planned as a parallel design, randomized, controlled, assessor-blinded, clinical study. One hundred twenty-eight patients diagnosed with CNP will be randomly assigned to either the TEA group or the PT group in a 1:1 ratio. Participants in the TEA group will receive 4 sessions of TEA treatment, while those in the PT group will receive 8 sessions of PT treatment over 4 weeks. An assessment of effectiveness based on the outcomes of the Neck Pain and Disability Scale (NPDS), cervical spinal angle, Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC), EuroQol-Five Dimension 3 level version (EQ-5D-3L), and Pressure Pain Threshold (PPT) will be conducted at baseline, and at 5, 9, and 13 weeks. The primary outcome is the mean change in the NPDS at 9 weeks. Adverse events (AEs) will be recorded at every visit.

Discussion:

The results of this study will be expected to provide useful information for the effectiveness and safety of TEA treatment compared to PT treatment for patients with CNP.

Trial registration:

Clinical Research Information Service of Republic of Korea (CRIS- KCT0003720), April 5, 2019.

1. Introduction

Neck pain is one of the most common musculoskeletal pains, with 26% to 71% of the adult population experiencing it.[1,2] In particular in the Republic of Korea, non-specific chronic neck pain (CNP), diagnosed as “Back pain (M54.0)”, is the ninth among all diseases, and the second among diseases treated by Korean medicine.[3] Neck pain recurs frequently, and it tends to repeat improvement and aggravation. It is likely to progress chronically, so this leads to an increase in the cost of medical services, and a decrease in the quality of life and work capacity of the worker.[4,5]

CNP refers to neck pain that lasts for more than 3 months without structural pathologic, or traumatic underlying causes or neurological abnormalities, such as myelopathy. CNP is classified as cervical spondylosis without myelopathy or radiculopathy (M47.8), Cervicalgia (M54.2), Myalgia, other (M79.18), based on the international classification of diseases-10 (ICD-10).[6]

Acupuncture is one of the treatments of complementary and alternative medicine, which is widely used in musculoskeletal pain diseases worldwide, and several clinical studies have been conducted on the acupuncture treatment of neck pain.[7–9] Thread Embedding acupuncture (TEA) is an immersion method that induces continuous stimulation by embedding a thread in acupuncture points, and employs the therapeutic mechanism of delivering stimulation generated in peripheral receptors to the central nerves. It is a new acupuncture that has been widely used in recent years, and it can produce not only the stimulation effect of normal acupuncture, but also continuous effect through the buried thread. This could allow longer-term effects to be maintained with relatively few procedures.[10] Recently, many clinical studies on TEA have been published in China.[11–13] In the Republic of Korea, studies of Polydioxanone (PDO) TEA, which is mainly used in Korea, have been carried out. Studies that applied PDO TEA to CNP include studies on the effectiveness and safety of TEA and Sham TEA,[14] and the comparison of TEA plus usual care to usual care.[15]

Physical therapy (PT) is widely used conservative therapy in the treatment of patients with CNP and chronic musculoskeletal pain,[16–19] and in particular, heat and interfering wave therapy is commonly used PT in the Republic of Korea.[20] However, no studies have compared the effectiveness and safety of PDO TEA in the treatment of patients with CNP to PT. Although a previous study compared the add-on effect of PDO TEA with the usual care,[15] there was no comparison with PT only, so it was difficult to examine the exact effectiveness, safety, and long-term continuous effect of TEA compared to PT, in the treatment of patients with CNP.

Therefore, based on the assumption that PDO TEA will be more effective than PT in the treatment of patients with CNP, we have planned a large-scale, randomized, controlled, and clinical trial (RCT).

2. Methods

2.1. Objective

The objectives of this clinical trial are twofold: We will evaluate the effectiveness of TEA by comparing the changes in the neck pain and disability scale (NPDS) at 9 weeks (8 weeks after randomization) between the TEA group and the PT group. Adverse events (AEs) that occur during the study will be investigated to evaluate the safety of TEA.

2.2. Study design

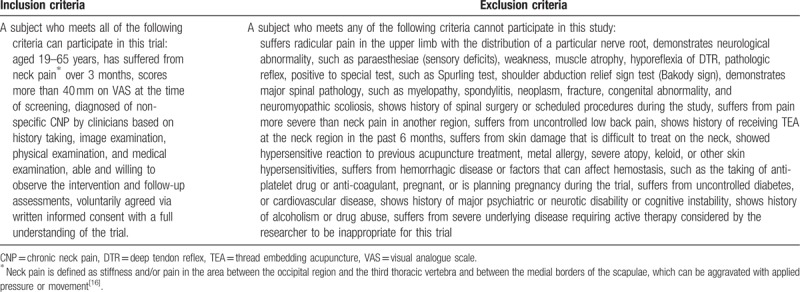

This clinical trial will be performed as a 2-arm parallel design, randomized, controlled, assessor-blinded, stratified block (male, female), and clinical trial. Figure 1 shows the suggested flowchart of this trial. This study is to recruit 128 applicants, who meet the criteria of inclusion and exclusion (Table 1).[14,15,21] A total of 128 patients with CNP are to be recruited from Daejeon University Dunsan Korean Medicine Hospital. Applicants will be recruited through advertisements posted on bulletin boards at hospitals, subway stations, apartments, subway cars, hospital homepages, newspapers, etc. Recruitment commenced in April 2019, and the trial is expected to end in December 2019.

Figure 1.

Study flow with outcome assessments.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

All applicants will receive a full explanation of this trial's protocol and will be provided an informed consent form and written explanation. Also, radiography and blood tests (including liver function test, blood clotting factors, inflammation-related enzymes, etc.) will be conducted at screening visit. Participants who are judged to be eligible for this trial according to criteria will be randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either the TEA group, or the PT group. The interventions will begin within 2 weeks of the screening. The subject of the TEA group will receive a total of four TEA treatments over 4 weeks, while the subject of PT group will receive a total of eight PT treatments over 4 weeks, followed by 3 follow-up visits, at 5, 9, and 13 weeks.

2.3. Sample size calculation

Based on the results of a previous study and clinical significance,[15,22] we assume that the mean difference (δ) between the changes in NPDS before and after intervention in each group is 11.5, and the standard deviation (SD, σ) is 20.67. We have applied a significance level of 5%, a power of 80%. As a result, a minimum of 51 participants are needed for each group. Also, considering the expected dropout rate of 20%, at least 64 subjects per group, for a total of 128 subjects, are required.

|

2.4. Randomization and blinding

Randomization will be conducted so as not to be biased, and be blinded to subjects and researchers. Statisticians who are not involved in the conduct and evaluation of clinical trials will randomly assign 64 patients to each group with the same probability of being selected, using the statistical program SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Stratified block randomization will be used. The generated randomization table will be kept by independent statisticians and the file will be protected from disclosure.

In this trial, blinding of practitioner and subject is impossible in intervention, due to the characteristics of the procedure. However, it is designed to as much as possible be assessor-blinded to control bias. Assessments will be conducted by researchers who have not performed the intervention and randomization. The assessor will ask only simple questions about the evaluation items and the contents to fill out the case report form (CRF). The assessor does not know what kind of treatment the subject is receiving.

2.5. Intervention

2.5.1. Thread embedding acupuncture

Table 2 summarizes the detailed information of TEA treatment.[10,15,23–34] The patients in the TEA group will receive a total of 4 TEA treatments over 4 weeks. The TEA with a diameter of 29 gauge, and a length of 30 or 40 mm (29X36DF, 29046DF, Dongbang Medical Co., Seongnam, Republic of Korea) will be selectively used considering the depth of penetration and the muscle condition of the subject (Fig. 2). Patients are to be placed in a sitting position, with the appropriate treatment site exposed. The practitioner will insert the disposable sterile TEA, and immediately withdraws it, without further stimulation. Among the pre-selected acupuncture point pools, 4 to 8 acupuncture points will be selected per side considering the region of pain, meridian diagnosis, motion, palpation with controlled finger pressure, and spinal malalignment. The practitioner will perform a perpendicular or oblique insertion on the paravertebral point of dorsal aspect, and oblique or transverse insertion on the lateral side of the thorax and cervical vertebrae to avoid the risk of damaging critical structures, such as the external jugular vein, or common carotid artery. Before and after the treatment, Practitioners will sterilize the neck region with cotton saturated with 78% alcohol. On the day of TEA treatment, strong motion or stimulation of the treated sites will be prohibited to prevent the embedded thread from protruding. All TEA treatments will be conducted by Korean Medicine doctors (KMDs) who have had TEA treatment experience of over 3 years.

Table 2.

TEA treatment details based on standards for reporting interventions in clinical trials of acupuncture (STRICTA) 2010 checklist.

Figure 2.

The polydioxanone thread embedding acupuncture used in this trial.

2.5.2. Physical therapy

The patients in the PT group will receive a total of 8 PT treatments over 4 weeks. In patients with chronic pain, PT has been performed 2 to 3 times a week with acupuncture, whereas TEA procedures are usually applied once a week, or once every 2 weeks.[27–33] Based on the results of previous clinical studies that evaluate the effect of adding TEA to usual care in the treatment of patients with non-specific CNP by using NPDS,[15] we have assumed that once-a-week treatment with TEA would have an equivalent clinical effect to 2 or 3 PTs per week. Interferential current therapy (ICT) (EDiT 400, Nemectron, Karlsruhe, Germany) and heat therapy using hot pack (DS-3860H, Daeshinelc Co, Bucheon, Republic of Korea) will be applied to the PT group in this trial. With the subject in the prone position, the ICT pads will be attached to 4 points of the neck pain region, and the neuromuscular system is stimulated by crossing 2 currents (4000 or 4100 Hz) to cause interference. Depending on the subject's condition, it will be applied with an intensity of 5 to 20 mA. An electric-heated hot pack heated to 40 to 50°C will be applied to the neck.[34] ICT and hot pack will be applied at the same time, and after attaching the ICT pad first, hot pack will be applied on it for about 15 minutes per session. All PT treatments will be conducted by KMDs who have had clinical experience of over 2 years. After the trial is completed, for compensation, the subjects in the PT group will receive one session of TEA treatment, upon request.

2.5.3. Cointerventions

All treatments for the improvement of CNP other than TEA or PT performed in this trial will be prohibited for all subjects. Medications that are considered to have no effect on this clinical trial (including other drugs for other diseases or AEs) will be allowed under the discretion of the researcher physician. Subjects will receive rescue medication (Acetaminophen 500 mg, up to 6 tablet per day), and will be instructed to take it only when their neck pain is so severe that it is unbearable. At each visit, the clinical research coordinator (CRC) will record on the CRF the total medication dosage (including rescue medication) used by the subject since the last visit. Subjects will be instructed to not take rescue medication from the day before assessments to the assessments of 5, 9, and 13 weeks. If a subject takes a drug without the report or judgment of a researcher, this can have a significant impact on the assessments of this clinical trial, so in this trial, the subject will be dropped.

2.6. Outcome measures

Assessments will be conducted at baseline and at 5 weeks (5W), 9 weeks (9W), and 13 weeks (13W). Table 3 shows the schedule for the assessments.

Table 3.

Schedule for the treatment and the outcome measurements.

The primary outcome is the mean change in the Neck Pain and Disability Scale (NPDS) score at 9W. NPDS consists of 20 items that assess neck movement, neck pain on emotion, and cognition, neck pain intensity, and the level of interference with daily life activity.[35] Each item consists of a 100-mm visual analogue scale (VAS) with numeric anchors of 0 (normal), 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (most severe) at 20 mm intervals. The total score is evaluated as 100 points, and the higher the score, the more severe the pain and dysfunction. The NPDS score is valid only if the subject self-checks more than 17 items.[7] This trial uses the Korean version of the NPDS with the reliability and validity already verified.[36]

The secondary outcomes include NPDS scores at other time points (5W, 13W), the clinical relevance, cervical spinal angle, Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), EuroQol-Five Dimension 3 level version (EQ-5D-3L), Pressure Pain Threshold (PPT), and Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC).

The clinical relevance will be assessed by using minimal clinically important difference (MCID). MCID is the minimum difference that a patient can feel to be clinically effective.[37] It is recommended that MCID should be considered in the assessments of chronic pain.[38] According to a study that verified the clinical relevance of the NPDS, the MCID was found to be greater than 11.5 points.[22] In this trial, the clinical relevance for result of this trial will be assessed by comparing the percentage of subjects indicating an improvement of more than 11.5 points (MCID) on the NPDS, of more than 30% (moderate CID), and of more than 50% (substantial improvement), respectively, between the 2 groups.[38]

Cervical spinal angle is the angle between the straight lines that connect the posterior edges of the C2 and C7 vertebrae, and in the normal case, it is between 31° and 40°.[39,40] In patients with CNP, the cervical spinal angle tends to decrease compared to acute,[41,42] and there is a significant relationship between neck pain and angle in the case of less than 20°.[43] In this trial, the cervical spinal angle of the baseline will be compared with that of 9W.

Depression and anxiety are all highly correlated with neck pain.[44] This study uses the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) as depression and anxiety measures, respectively.[45,46] The BDI-II consists of 21 items, each of which is rated on a Likert scale ranging 0 to 3, with a total score ranging 0 to 63 points. The BAI also consists of 21 items, each of which is rated ranging 0 to 3, with a total score ranging 0 to 63 points. For this trial, the Korean versions of BDI-II and BAI will be used.[47,48]

EuroQol-Five Dimension 3 level version (EQ-5D-3L) is the most widely used questionnaire to assess the quality of life, and consists of the EQ-5D index and the EQ-5D VAS. The Korean version of the EQ-5D-3Lwill be used for this trial.[49,50]

Pressure Pain Threshold (PPT) will be measured twice on both sides of the neck by digital algometer (FPX 25, Wagner Instrument., Greenwich, CT), and the mean value (kg/cm2) will be used. The 3 measurement points are as follows;

-

1.

GB21: the upper trapezius,

-

2.

the insertion point of the levator scapulae muscle, and

-

3.

the point extending 1.5 cm outward from the sixth cervical vertebra.[51]

Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) will be used.[52] Subjects will assess for the improvement of symptoms they have felt before and after treatment. The subjects will choose one item from 7 categories of responses to by how much the neck pain has been reduced compared with before treatments in this trial.

2.7. Adverse events

In this trial, AEs are defined as all unintentional medical findings newly observed during this clinical trial. The researcher examines the AEs at each visit based on vital sign, history taking, and other examinations. Also, the subject will be instructed to voluntarily report AEs frequently, and the researcher should confirm them through medical examination. All identified AEs will be recorded on the CRF, without reference to their association with interventions. If severe AEs (SAEs) occur, the researchers will temporarily discontinue the treatment of the subject in this clinical trial. If continuous treatment is judged to be hazardous to the subject and the AE is associated with treatment, the researchers will permanently discontinue the participation of the subject in this trial.

Local discomforts after the TEA treatments could generally last about 2 days. Local discomforts that last more than 2 days after TEA treatment will be classified into AE from 2 to 7 days (delayed AE) and AE for more 7 days, and will be analyzed and reported. This is based on the previous study,[53] which reported AEs from 1 to 7 days after dry needling treatment as delayed AEs, and reflects that local discomforts after TEA treatment may last longer than simple dry needling, due to the continuous stimulation by PDO.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses will be conducted as a 2-sided test, and the significance level will be set at 5%. The statistical program SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) will be used. Multiple imputations will be used when missing values are encountered.

The data obtained from this trial will be analyzed by Full Analysis Set (FAS) and Per Protocol (PP) set. The FAS refers to the analysis method of minimizing the subjects excluded from the analysis among the randomly assigned subjects by excluding the subjects from the analysis only when there is a justifiable reason. The PP refers to the method of analyzing a group of subjects who have participated in more than 75% (3 or more TEA, 6 or more PT) of the interventions according to this clinical trial's protocol, for whom all of the assessment variables have been completely measured, and who have not violated this trial's protocol.

The descriptive statistics on the variables, such as demographic characteristics, sex, age, medical history, and drug administration will be presented for each treatment group. To verify the heterogeneity between the 2 groups at baseline, for continuous data, the mean and SD will be presented and analyzed using a Wilcoxon rank sum test or independent t test. The 95% confidence intervals will be provided as needed. For categorical data, frequency and percentiles will be presented and analyzed using the Fisher Exact test or Chi-square test. The primary outcome variable is the mean changes of NPDS score at 9W compared with the baseline. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) will be used with NPDS score at baseline as covariate and each treatment group as fixed factor. Secondary outcome variables will be analyzed in the same way as the primary outcome variables. If outcome variables are categorical variables, they will be analyzed using the Fisher Exact test or Chi-square test. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test or Paired t test will be used to analyze differences in measured values between pre- and post-treatment in each group. Repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) will be performed to examine the differences in symptom change by visit. Dunnett procedure will be used for multiple comparisons. As needed, a subgroup analysis of outcome variables such as demographic variables (age, gender, duration of illness at baseline, etc.), whether or not rescue medications were taken, and the amount of rescue medications taken can be performed.

The safety assessment will be performed by analyzing the incidence of AEs and SAEs. The collected safety data will be summarized and described descriptively. AEs will be recorded and presented as descriptive statistics.

2.9. Withdrawal and dropout

During the study, if the violation of inclusion or exclusion criteria of the subject is found, or if the continuous participation of subject is difficult due to the occurrence of AEs or SAEs in the subject, the subject will be dropped from this trial under the judgment of the principal investigator. The researchers will record whether each subject participating in this trial completed it or not, and if the subject is dropped, record the reasons for stopping participation in this trial.

2.10. Ethics and monitoring

The protocol was designed based on the Helsinki Declaration and the Korean Clinical Practice Guidelines, approved by the institutional review board of Daejeon University Dunsan Korean Medicine Hospital (DJDSKH-19-BM-04), and registered with the Clinical Research Information Service (identifier: KCT0003720). All subjects participating in this trial are to receive sufficient explanations for this trial, and may voluntarily decide to participate or to discontinue the trial at any time. Electronic data will be kept in a secure database to prevent personal information leakage, and documents related to research will be kept under lock and key at Daejeon University Dunsan Korean Medicine Hospital. After the study is completed, an independent researcher will edit and classify the data for statistical analysis. Monitoring of the data and performance of the trial will be conducted by a third party who is independent of this trial. The results of this trial are to be published later in a peer-reviewed paper.

3. Discussion

This trial is designed to compare the clinical effectiveness and safety of TEA with that of PT in the treatment of patients with CNP. Although TEA treatment studies for CNP have been reported,[14,15] to the best of our knowledge, no RCT investigating the effectiveness and safety of the TEA treatment compared with PT in the treatment of patients with CNP has been reported. Therefore in this trial, we will set the PT group as a control group to evaluate the differences in therapeutic effects caused by the TEA.

The researchers will diagnose the CNP of the subjects based on radiography, clinical symptoms (neck pain), medical opinion of the clinician, physical examination, etc., and then judge whether or not the subjects can participate in this trial. History taking and blood tests will be conducted, and their results can be used to exclude subjects who have hemostatic disorders, so that should prevent SAEs that could occur as a result of the TEA treatment.

However, practitioners and patients could not be blinded, because of the obvious differences in interventions. For this reason, non-specific effects that are not associated with interventions, such as placebo or treatment expectations, could occur, and it is not possible to exclude the possibility that non-specific effects will affect the outcome in favor of the TEA group. Despite these limitations, this is the first clinical trial to compare the effectiveness and safety of TEA with PT treatment in patients with CNP. Because of the RCT design of this trial, the results are expected to provide valuable data for confirming the effectiveness and safety of TEA.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Jae Ik Kim, Young Il Kim.

Data curation: Ojin Kwon, So-Young Jung.

Formal analysis: Ojin Kwon.

Funding acquisition: Chang-Hyun Han.

Investigation: Jae Ik Kim.

Methodology: Eunseok Kim, Ju Hyun Jeon, Jin Youp Kim.

Project administration: So-Young Jung.

Software: Ojin Kwon.

Supervision: Young Il Kim, Chang-Hyun Han.

Validation: So-Young Jung.

Writing – original draft: Jae Ik Kim.

Writing – review & editing: Eunseok Kim.

Chang-Hyun Han orcid: 0000-0003-4285-3063.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AE = adverse event, ANCOVA = analysis of covariance, ANOVA = analysis of variance, BAI = beck anxiety inventory, BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory II, CNP = chronic neck pain, CRC = clinical research coordinator, CRF = case report form, EQ-5D-3L = EuroQol-Five Dimension 3 level version, FAS = full analysis set, ICD = international classification of diseases, ICT = interferential current therapy, KMD = Korean Medicine doctor, MCID = minimal clinically important difference, NPDS = Neck Pain And Disability Scale, PDO = polydioxanone, PGIC = patient global impression of change, PP = per protocol, PPT = pressure pain threshold, PT = physical therapy, RCT = randomized controlled clinical trial, SAE = severe adverse event, SD = standard deviation, TEA = thread embedding acupuncture, VAS = visual analogue scale.

JIK and YIK contributed equally to this study.

This trial is currently in the recruitment phase and recruitment began in April 2019. The trial is expected to be completed by the end of 2019, and the results of this trial are to be published later in a peer-reviewed paper.

The data from this trial are to be made accessible by contacting the corresponding author. The trial findings are to be disseminated through open-access journals and at national and international conferences.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: This study protocol was prepared according to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Intervention Trials (see Appendix 1, http://links.lww.com/MD/D160) and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the hospitals to which the participating research centers belong: Daejeon University Dunsan Korean Medicine Hospital (DJDSKH-19-BM-04). The study is to be performed in accordance with the approved protocol, and written informed consent is to be obtained from every participant.

This study was financially supported by grants from project KSN1522121 of the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (KIOM), Republic of Korea.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

References

- [1].Brattberg G, Thorslund M, Wikman A. The prevalence of pain in a general population. The results of a postal survey in a county of Sweden. Pain 1989;37:215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hogg-Johnson S, van der Velde G, Carroll LJ, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in the general population: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2009;32:S46–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kim ST, Kim YI. 2017 National health insurance statistical yearbook. National Health Insurance Service, Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service 2018. 614634. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cote P, van der Velde G, Cassidy JD, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in workers: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2009;32:S70–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hoy D, March L, Woolf A, et al. The global burden of neck pain: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1309–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Binder AI. Cervical spondylosis and neck pain. BMJ 2007;334:527–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Trinh K, Graham N, Irnich D, et al. Acupuncture for neck disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;5:CD004870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Witt CM, Jena S, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture for patients with chronic neck pain. Pain 2006;125:98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Salter GC, Roman M, Bland MJ, et al. Acupuncture for chronic neck pain: a pilot for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2006;7:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Seoul, Acupuncture and Moxibustion Textbook Compilation Committee. The Acupuncture & Moxibustion Medicine. 2012;Jipmoondang, [Google Scholar]

- [11].Qin W, Zhao K, Yang H. Effect of acupoint catgut embedding therapy combined with Chinese medicine for nourishing the kidneys and promoting blood circulation and improving blood glucose and lipid levels as well as the pregnancy rate in obese PCOS patients with infertility. Exp Ther Med 2016;12:2909–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Garcia-Vivas JM, Galaviz-Hernandez C, Fernandez-Retana J, et al. Transcriptomic profiling of adipose tissue in obese women in response to acupuncture catgut embedding therapy with moxibustion. J Altern Complement Med 2016;22:658–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chen GZ, Xu YX, Zhang JW, et al. Effect of acupoint catgut-embedding on the quality of life, reproductive endocrine and bone metabolism of postmenopausal women. Chin J Integr Med 2010;16:498–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kim E, Kim HS, Jung SY, et al. Efficacy and safety of polydioxanone thread embedded at specific acupoints for non-specific chronic neck pain: a study protocol for a randomized, subject-assessor-blinded, sham-controlled pilot trial. Trials 2018;19:672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kim E, Kim YS, Kim YI, et al. Effectiveness and safety of polydioxanone thread-embedding acupuncture as an adjunctive therapy for patients with chronic nonspecific neck pain: A randomized controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med 2019;25:417–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Facci LM, Nowotny JP, Tormem F, et al. Effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and interferential currents (IFC) in patients with nonspecific chronic low back pain: randomized clinical trial. Sao Paulo Med J 2011;129:206–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yesil H, Hepguler S, Dundar U, et al. Does the use of electrotherapies increase the effectiveness of neck stabilization exercises for improving pain, disability, mood, and quality of life in chronic neck pain?: A randomized, controlled, single-blind study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018;43:E1174–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Acedo AA, Luduvice Antunes AC, Barros dos Santos A, et al. Upper trapezius relaxation induced by TENS and interferential current in computer users with chronic nonspecific neck discomfort: an electromyographic analysis. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2015;28:19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fuentes JP, Armijo Olivo S, Magee DJ, et al. Effectiveness of interferential current therapy in the management of musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther 2010;90:1219–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Suh CY, Lee YJ, Kim M-r, et al. A web-based survey for assessment of Korean medical treatment clinical practice patterns for neck pain and cervical intervertebral disc displacement. J Acupunct Res 2016;33:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kuorinka I, Jonsson B, Kilbom A, et al. Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Appl Ergon 1987;18:233–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jorritsma W, Dijkstra PU, de Vries GE, et al. Detecting relevant changes and responsiveness of neck pain and disability scale and neck disability index. Eur Spine J 2012;21:2550–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Blossfeldt P. Acupuncture for chronic neck pain--a cohort study in an NHS pain clinic. Acupunct Med 2004;22:146–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Liang ZH, Di Z, Jiang S, et al. The optimized acupuncture treatment for neck pain caused by cervical spondylosis: a study protocol of a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Trials 2012;13:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lee S, Nam D, Leem J, et al. Efficacy and safety of Myofascial-meridian Release Acupuncture (MMRA) for chronic neck pain: a study protocol for randomized, patient- and assessor-blinded, sham controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med 2016;16:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kwon K. The analysis on the present condition of thread-embedding therapy papers published in journal of Korean medicine. J Korean Med Ophthalmol Otolaryngol Dermatol 2014;27:16–44. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jiang Q. Clinical study on the effect of catgut implantation at acupoint and warm needling moxibustion on treating chronic lumbar muscle strain [dissertation]. Guagzhou: Guagzhou University of Chinese Medicine; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ku HN. Clinical observation of acupoint catgut embedding therapy for lumbar disc herniation[dissertation]. Guagzhou: Guagzhou University of Chinese Medicine; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tang J, Liao L. Seventy-two cases of sciatica treated by catgut point-embedding therapy. J Tradit Chin Med 2007;27:28–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Li W, Li Y, Yang Z. Clinical efficacy of acupuncture combined with embedding treatment on shoulder-hand syndrome. J Ningxia Med Univ 2012;34:1348–9. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jang HG, Woo CH, Ahn HD, et al. A clinical four case studies on chronic low back pain treated by needle embedding therapy. J Korea CHUNA Man Med Spine Nerves 2014;9:45–55. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lee SM, Ji YS, Jeon JH, et al. Effect of needle-embedding & acupuncture therapy on shoulder pain in Behcet disease patient: A case report. J Korean Acupunct Moxib Soc 2013;30:219–24. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lee HY, Youn HM, Kim WI. Clinical study about shoulder pain by oriental medical treatment and oriental-western medical treatment. J Korean Pharmacopunct Inst 2008;11:97–110. [Google Scholar]

- [34].The Society of Korean Medicine Rehabilitation. Oriental rehabilitation medicine. Seoul: Koonja; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wheeler AH, Goolkasian P, Baird AC, et al. Development of the neck pain and disability scale. Item analysis, face, and criterion-related validity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24:1290–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lee JS, Suh KT, Kim JI, et al. Validation of the Korean version of the neck pain and disability scale. Asian Spine J 2013;7:178–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials 1989;10:407–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 2008;9:105–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gore DR, Sepic SB, Gardner GM. Roentgenographic findings of the cervical spine in asymptomatic people. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1986;11:521–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Cailliet R, et al. Cobb method or Harrison posterior tangent method: which to choose for lateral cervical radiographic analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2072–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Harrison DD, Harrison DE, Janik TJ, et al. Modeling of the sagittal cervical spine as a method to discriminate hypolordosis: results of elliptical and circular modeling in 72 asymptomatic subjects, 52 acute neck pain subjects, and 70 chronic neck pain subjects. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:2485–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Askin A, Bayram KB, Demirdal US, et al. The evaluation of cervical spinal angle in patients with acute and chronic neck pain. Turk J Med Sci 2017;47:806–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].McAviney J, Schulz D, Bock R, et al. Determining the relationship between cervical lordosis and neck complaints. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2005;28:187–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Blozik E, Laptinskaya D, Herrmann-Lingen C, et al. Depression and anxiety as major determinants of neck pain: a cross-sectional study in general practice. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2009;10:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the BDI-II. San Antonio. TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, et al. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988;56:893–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kim JH, Lee EH, Hwang ST, et al. Korean-Beck Depression Inventory II. Daegu: Korea Psychol; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kim JH, Lee EH, Hwang ST, et al. Korean-Beck Anxiety Inventory. Daegu: Korea Psychol; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Seong SS, Choi CB, Sung YK, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life using EQ-5D in Koreans. J Korean Rheum Assoc 2004;11:254–62. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kim MH, Cho YS, Uhm WS, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Korean version of the EQ-5D in patients with rheumatic diseases. Qual Life Res 2005;14:1401–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Irnich D, Behrens N, Molzen H, et al. Randomised trial of acupuncture compared with conventional massage and “sham” laser acupuncture for treatment of chronic neck pain. BMJ 2001;322:1574–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Farrar JT, Young JP, Jr, LaMoreaux L, et al. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain 2001;94:149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Cotchett MP, Munteanu SE, Landorf KB. Effectiveness of trigger point dry needling for plantar heel pain: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther 2014;94:1083–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.