Abstract

Background

Amphotericin B (AmB) as a liposomal formulation of AmBisome is the first line of treatment for the disease, visceral leishmaniasis, caused by the parasite Leishmania donovani. However, nephrotoxicity is very common due to poor water solubility and aggregation of AmB. This study aimed to develop a water-soluble covalent conjugate of gold nanoparticle (GNP) with AmB for improved antileishmanial efficacy and reduced cytotoxicity.

Methods

Citrate-reduced GNPs (~39 nm) were functionalized with lipoic acid (LA), and the product GNP-LA (GL ~46 nm) was covalently conjugated with AmB using carboxyl-to-amine coupling chemistry to produce GNP-LA-AmB (GL-AmB ~48 nm). The nanoparticles were characterized by dynamic light scattering, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and spectroscopic (ultraviolet–visible and infrared) methods. Experiments on AmB uptake of macrophages, ergosterol depletion of drug-treated parasites, cytokine ELISA, fluorescence anisotropy, flow cytometry, and gene expression studies established efficacy of GL-AmB over standard AmB.

Results

Infrared spectroscopy confirmed the presence of a covalent amide bond in the conjugate. TEM images showed uniform size with smooth surfaces of GL-AmB nanoparticles. Efficiency of AmB conjugation was ~78%. Incubation in serum for 72 h showed <7% AmB release, indicating high stability of conjugate GL-AmB. GL-AmB with AmB equivalents showed ~5-fold enhanced antileishmanial activity compared with AmB against parasite-infected macrophages ex vivo. Macrophages treated with GL-AmB showed increased immunostimulatory Th1 (IL-12 and interferon-γ) response compared with standard AmB. In parallel, AmB uptake was ~5.5 and ~3.7-fold higher for GL-AmB-treated (P<0.001) macrophages within 1 and 2 h of treatment, respectively. The ergosterol content in GL-AmB-treated parasites was ~2-fold reduced compared with AmB-treated parasites. Moreover, GL-AmB was significantly less cytotoxic and hemolytic than AmB (P<0.01).

Conclusion

GNP-based delivery of AmB can be a better, cheaper, and safer alternative than available AmB formulations.

Keywords: gold nanoparticle, amphotericin B, antileishmanial, macrophage uptake, ergosterol, immunostimulator

Introduction

Metallic nanoparticles (NPs) and their compounds synthesized by chemical or biological methods have been used for treatment and detection of diseases since ancient times.1 Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) and gold nanoparticle (GNPs) is most common due to their reduced cytotoxicity.2 AgNPs synthesized by green chemistry3 or conjugated with antibiotics4,5 have shown enhanced antimicrobial efficacy. Biosynthesized GNPs, AgNPs, and Au–Ag bimetallic NPs were used for control of biofilm.6,7 As antileishmanial agents, bothAgNPs and GNPs have shown promising results.8 GNP-based delivery of small molecules or drugs,9 peptides,10 nucleic acids,11 and antimicrobial agents12 has shown improved efficacy due to targeted delivery of the payload. GNP-based drug delivery is popular due to ease of GNP functionalization with antimicrobial agents,13 biological or chemical methods of synthesis,14 controlled drug delivery,15 and multiple targets of bactericidal action with their ability to penetrate biological membranes.16 Here, we report the synthesis, characterization, and efficacy of GL-AmB, a covalent conjugate of GNP with amphotericin B (AmB) against parasite Leishmania donovani (LD).

AmB is a polyene antibiotic with poor water solubility and high toxicity due to its self-aggregation.17 It was first licensed in the 1950s.18 Since then, AmB has been extensively used as a deoxycholate formulation (Fungizone) in a micellar form to treat systemic fungal infections.19 However, due to severe nephrotoxicity, use of Fungizone became limited20 against visceral leishmaniasis (VL),21 a disease caused by Leishmania parasite species22 that becomes fatal if untreated. This prompted development of several lipid-based complexes of AmB (AmBisome, Abelcet, and Amphocil) with improved AmB delivery and reduced cytotoxicity23 for the treatment of leishmaniasis. However, lipid-based complexes of AmB bring high cost in treatment for patients with leishmaniasis24 and systemic fungal diseases25 compared to standard AmB or AmB-deoxycholate formulation. In parallel, micelle-based26 and NP-based27,28 AmB delivery with improved antileishmanial efficacy showed promise as an alternative to costly liposomal formulations.

Novel NP-based AmB formulations combined with polysaccharides,29 dendrimers,30 iron NPs,31 AgNPs,32,33 and carbon nanotubes34 were developed. AmB derivatives with modified functional groups showed more enhanced and specific binding toward fungal ergosterol than cholesterol35 with increased ion channel and fungicidal activity.36 Therefore, treatment with a combination of NPs with AmB and/or AmB derivatives could be a very effective strategy for improving the efficacy of and reducing the cytotoxicity of AmB. AmB nanoemulsions against experimental VL37,38 and AmB coated with polymeric NPs had shown efficacy in oral delivery of AmB in a mouse model of VL.39 Photo-induced antileishmanial activity was observed with AmB-AgNPs which were synthesized using plant phytochemicals.40 Improved photodynamic therapy was observed for GNP-conjugated nanorods over nanospheres, indicating the imporatance of NP shape in efficacy.41 Although there are growing developments of NPs as antileishmanial agents,8,28,42 there is no report yet about covalent conjugation or functionalization of GNPs with AmB or AmB derivatives for enhanced efficacy against LD. Leishmaniasis, the second largest infectious disease after malaria and one of the “most neglected” diseases, is spread by 23 Leishmania species in more than 98 countries. Among all types, the VL caused by LD is life threatening and is most difficult to control. As per WHO report, a total of 0.7–1.0 million new leishmaniasis cases are estimated with an alarming 26,000–65,000 death toll every year.43

Herein, we present the synthesis of GL-AmB, where the –COOH group present in the linker (lipoic acid (LA)) was used to conjugate with the –NH2 group present in the mycosamine ring of AmB through amide linkage. The mechanism of action of GL-AmB was evaluated, with naked AmB as a comparative arm against LD.

Materials and methods

Materials

M-199, RPMI-1640, and yeast peptone dextrose medium, HAuCl4•3H2O, Giemsa dye, Trypan blue, MTT, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate dye, N-acetyl l-cysteine (NAC), diphenyleneiodonium chloride, proteinase K, ergosterol (ERG), diphenyl hexatriene (DPH), RNase A, Griess reagent, 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine, TRIZOL, nitro blue tetrazolium, 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC), lipoic acid, sulfo-N-hydroxy succinamide (NHS), AmB as Fungizone, the Glutathione Colorimetric Assay Kit, the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay kit, the Apoptosis Detection Kit, and all solvents were from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St Louis, MO, USA). Trisodium citrate was from Merck (USA). The QIAamp DNA Mini kit and RNeasy Mini Kit were from Qiagen (NV, Venlo, the Netherlands). The cDNA synthesis kit was from Hoffmann-La Roche (Basel, Switzerland). The cytokine ELISA kit was obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA) for mouse interferon (IFN)-γ, IL-12, and IL-10, respectively. The RAW 264.1 THP-1 cell line was obtained commercially from the National Cell Repository, NCCS, Pune, India. For the hemolysis assay, blood samples from healthy volunteers were collected based on ethical approval from RMRIMS-Patna (Reference no. 21/RMRI/EC/2017) and the donor’s written informed consent.

Methods

Synthesis and conjugation of GNP with AmB

Reactions were done at room temperature unless mentioned. GNPs were synthesized according to the method of Turkevich et al44 by reduction of HAuCl4•3H2O solution (0.5 mM) in 0.05% trisodium citrate after dilution with double-distilled water (DDW) and heating at 75–80 °C for 5–10 min. Synthesis of red GNPs was confirmed by measuring absorbance at 530 nm. The concentration and molar extinction coefficient of GNPs vary with size during reduction of HAuCl4. Therefore, the absolute amount of Au (μg/mL), rather than the molar concentration, was used as a measure of GNP concentration. GNPs were functionalized with LA and then conjugated with AmB using EDC/NHS coupling chemistry45 with a few modifications. GNP solution (10 mL) was mixed with 0.1 mL (0.35 M) of LA and incubated for 12 h at 4 °C with constant stirring. The mixture was centrifuged at 12000×g for 15 min, washed with phosphate buffer (PB) (10 mM Na phosphate, pH 7.2), and a pellet of GL was suspended in 5 mL of PB. GL (1.25 mL) was mixed with 45 μM EDC and 40 μM NHS, and incubated for 3 min. Then, 0.1 mL of 50 mg/mL of AmB (dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)) and 0.35 mL of DDW were added. The mixture (~1.75 mL) was kept at constant stirring for 2 h to allow formation of a covalent amide bond between GL and AmB.46 The reaction mixture was centrifuged, washed 10 times with PB, and then stored in a suspension of 1 mL of PB at 4 °C for further use. After measuring the amount of unbound AmB by ultraviolet (UV) spectroscopy, the ratio of GNP:AmB in the GL-AmB conjugate was found to be 245 μg/mL:4.2 mg/mL (4.55 mM AmB), indicating ~84% conjugation efficiency of AmB in GL-AmB. Several batches of GL-AmB were prepared similarly and stored in PB buffer.

Quantification of AmB in GL-AmB by HPLC

Efficiency of conjugation of AmB in GL-AmB was measured by HPLC determination of AmB at 408 nm by UV detector.47 GL-AmB (~4.2 mg/mL of AmB) was diluted 1:24 with DDW and 10 μL was injected into the HPLC instrument (L-2000 series; Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and separated by reverse-phase C18 columns (Zorbax 300SB, dimension 4.6 mm×250 mm, particle size 5 μM; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with an isocratic mobile phase of acetonitrile:water:acetic acid (60:35:5) maintaining a flow rate of 1 mL/min. In parallel, 5 mg/mL of AmB was diluted 1:24 in DDW and analyzed similarly in HPLC. Concentrations of AmB (dissolved in mobile phase) used for generation of standard curves were 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL.

Characterization of GL-AmB NPs

NPs were analyzed by UV–visible spectrophotometer, dynamic light scattering, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), and TEM. The hydrodynamic diameter, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential were determined on a Beckman Coulter (Brea, CA, USA) Delsa nano submicron particle size and zeta potential analyzer as per standard procedures. For FT-IR analysis, purified NPs (GL and GL-AmB) and powdered AmB were pelletized with KBr and scanned over a range of 4000–400 cm−1 in a PerkinElmer Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA) Spectrum 400 spectrometer. NPs were processed and analyzed by TEM (JEOL-JEM 2010; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) analysis as described.48 Briefly, NPs (100 µM) were diluted with DDW 1:1. Further, 20 µL of sample was loaded on carbon-coated copper grid without gold coating and air dried for 10 min under vacuum. The grid chamber was placed in the TEM room and incubated in the dark at 10–20 °C for 2 h. Finally, the grid chamber was loaded on the TEM stage for analysis and images were captured from different zones with different resolution. The powder X-ray diffraction (pXRD) analysis was carried out for GL-AmB in a Rigaku TTRX-III diffractometer using Cu-Kα (λ=1.54 Å) as the X-ray radiation source and a scan range of 10–80°.

Stability studies of GL-AmB conjugate

Stability of GL-AmB (100 μM) was measured by measuring the release of free AmB in PBS buffer (PB containing 150 mM NaCl) and in freshly isolated human plasma at pH 7.4.49 The incubation mixture of GL-AmB and human serum or PBS with final AmB concentration of 100 μM was incubated at 37 °C for 72 h. After 4, 8, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h, the mixture was centrifuged at 15000×g for 10 min and absorbance of supernatant was taken at 360 nm. The percentage of AmB release was estimated47 by considering the absorbance of 100 μM standard AmB as 100%. GL-AmB present in PBS or plasma was treated with proteinase K (1 μg/mL) for 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 h to accelerate cleavage of the amide bond in GL-AmB when required.

In vitro assay against promastigotes

LD (MHOM/IN/1983/AG83) promastigotes were cultured as described.50 Log phase cells (1×106 cells/ml) were treated with GNP/GL (0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, and 10 μg/mL) and AmB/GL-AmB (0.5, 1, 5, 20, 50, and 100 nM) for 3–4 days and cell viability measured by Trypan blue exclusion and MTT reduction method after every 24 h using standard procedures. After 48 h, the drug concentration showing 50% killing of the parasite was considered the IC50 for that drug. Drug-treated cells were preincubated with 1 mM NAC when required.51

Assay against intracellular amastigotes in macrophages

RAW 264.1 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium and infected with promastigotes as described.33 Parasite-infected macrophages, grown for another 24 h, were treated with different concentrations of GNP/GL (0.5, 1, 2.5. 5, and 10 μg/mL) and AmB/GL-AmB (20, 50, 100, 250, 500, and 1000 nM) for 48 h. Chamber slides were washed and supplemented with fresh medium and kept in a CO2 incubator for another 12 h. Untreated parasite-infected macrophages were used as control. Amastigotes from 100 macrophage nuclei per well were counted, at least, under the oil immersion objective of a light microscope (Eclipse TS100; Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) after methanol fixation and Giemsa staining of the slides.

Cytotoxicity assays

Cytotoxicity was measured against human THP-1 cells by MTT assay. Briefly, THP-1 cells were cultured with RPMI-1640 medium in 6-well plates (2×106 cells/well) and treated with GNP/GL (2.5, 5, 10, and 25 μg/mL) and AmB/GL-AmB (2.7, 5.5, 11, 22, and 35 μM) for 48 h and cell viability was measured as described.52

Hemolysis assay

Human erythrocytes were incubated (4×108 cells/mL in PBS) in the presence of GNP/GL (2.5, 10, and 25 μg/mL) and AmB/GL-AmB (1, 54, 80, and 108 μM) for 4 h at 37 °C. The samples were centrifuged at 1500×g for 5 min and the absorbance of supernatant was measured at 560 nm. Relative hemolysis was measured52 by considering hemolysis of 100 μM AmB-treated erythrocytes as 100%.

Determination of ergosterol from promastigotes by HPLC

Promastigotes (1×106 cells/mL) were treated with GNP (10 µg/mL) and AmB/GL-AmB (0.2 µM) for 6 h. Pellets of treated and untreated cells (1×107 cells) were homogenized in 0.5 mL of 2:1 chloroform/methanol mixture for 30 min and then ERG was extracted for HPLC analysis.53 The isocratic mobile phase of methanol:water (95:5) with a flow rate of 1 mL/min was used for separation. Peak ERG was determined at 282 nm using a UV-detector. Concentrations of ERG (dissolved in mobile phase) used for generation of standard curves were 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL.

Determination of AmB uptake of macrophages by HPLC

RAW 264.1 (1×106 cells/ml) cells were treated with 300 µM of AmB and GL-AmB for 1,2, 4, 6, 12 and 24 h. Cells were harvested, washed five times in PBS, and the cell pellet lysed with 0.5 mL of 1% Triton-X-100 (in PBS) for 20 min at 37 °C. Supernatant (0.2 mL) obtained after centrifugation was mixed with 0.2 mL DMSO, mixed by shaking, and then the top layer (0.2 mL) was taken after centrifugation for HPLC analysis.54,55 Samples (10 μL) were analyzed by HPLC as described earlier.

Measurement of intracellular thiol

Promastigotes (2×106 cells/well) were treated with GNP (10 μg/mL) and AmB/GL-AmB (0.5 μM) for 1, 2, 4, 6, and 12 h. The trotal reduced glutathione (GSH) content was measured56 by the Glutathione Colorimetric Assay Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Measurement of membrane fluidity by fluorescence anisotropy

Decreased fluorescence anisotropy (FA), measured by DPH fluorescence, indicates an increase in membrane fluidity. Promastigotes (2×106 cells/mL) were treated with GNP (2.5 and 10 μg/mL) and AmB/GL-AmB (0.1 and 0.5 μM) for 6 and 12 h. Washed cells were suspended in PBS and incubated with DPH (2 μM) for 1 h at 37 °C. The membrane-bound DPH probe was excited at 365 nm and the intensity of emission was recorded at 430 nm in a spectrofluorometer (LS 55; PerkinElmer Inc.). The FA value was calculated using the equation: FA=[(III–I⊥)/(III+2I⊥)], where III and I⊥ are the fluorescent intensities oriented, respectively, parallel and perpendicular to the direction of polarization of the excited light.57

LDH assay for determination of membrane leakage

Intracellular LDH release is correlated with cell membrane damage and necrosis.58 Promastigotes (5×106 cells/mL in PBS buffer) were treated with GNP (2.5, 10, and 2.5 μg/mL) and AmB/GL-AmB (0.05, 0.2, and 0.5 μM) for 6 and 12 h. Untreated and H2O2-treated cells (0.5 and 1 mM, for 4 h) were used as negative and apoptotic controls, respectively. LDH assay was done according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the LDH assay kit. LDH released by 1% Triton-X-100-treated cells was considered 100%.

Cytokine measurement assay

Parasite-infected macrophages (1×106 cells/well) were kept in 6-well plates and treated with GNP (10 µg/mL) and AmB/GL-AmB (0.2 µM) for 6 h. Cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-12, and IL-10) released in culture supernatant (200 μL in each assay) at different time points (12, 24, 36, 48, and 72 h) were measured by the cytokine ELISA kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

DNA fragmentation assay

Parasites (1×106 cells/mL) were incubated with GNP (7.5 μg/mL) and AmB/GL-AmB (0.05 and 0.15 μM) for 6 h. Untreated and H2O2-treated (2 and 4 mM) parasites59 were taken as negative and positive controls, respectively. Cells (1×107 cells) were suspended in 200 µL of PBS followed by sequential addition of 200 μL lysis buffer from the QIAamp DNA Mini kit, proteinase K (200 μg/mL), and RNase A (40 μg/mL). The mixture was incubated for 3 h at 37 °C followed by phenol/isopropanol/chloroform extraction. Genomic DNA was precipitated by addition of sodium acetate (pH 5.0) and ice-cold ethanol. Pellet was centrifuged at 15000×g for 15 min, washed, dried, and then dissolved in 30 μL of TE (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA) buffer. DNA aliquots (10 μL) were electrophoresed on 1.5% agarose gel and visualized under UV illumination after ethidium bromide staining.

Flow cytometry of Annexin-V–FITC/propidium iodide-bound promastigotes

Annexin V-FITC (AV)/propidium iodide (PI) binding of parasites was assessed using the AV Apoptosis Detection Kit. Briefly, promastigotes (1×106 cells/mL) were treated with GNP (5 and 10 μg/mL) and AmB/GL-AmB (0.1 and 0.25 μM) for 6 h. Untreated and H2O2-treated (0.1 and 0.2 mM) cells were taken as negative and apoptotic controls, respectively. Cells were harvested, washed, and dissolved in 1 mL PBS followed by mixing with sequential addition of 5 μL PI, 20 μL of binding buffer, and 5 μL of AV. After 15-min incubation, cells were analyzed by a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, CA, USA).

In vitro activity against Candida albicans

Candida albicans (ATCC-10231) were grown in yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) medium at 30°C for 24 h. Cell number were adjusted to 1×106 cells/ml and cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with (2%) glucose. Cells were further treated with GNP (1, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 and 40 μg/ml) and AmB /GL-AmB (1, 2, 4, 8, 16 and 40 μM) for 48 h and IC50 was determined by MTT assay as described.60

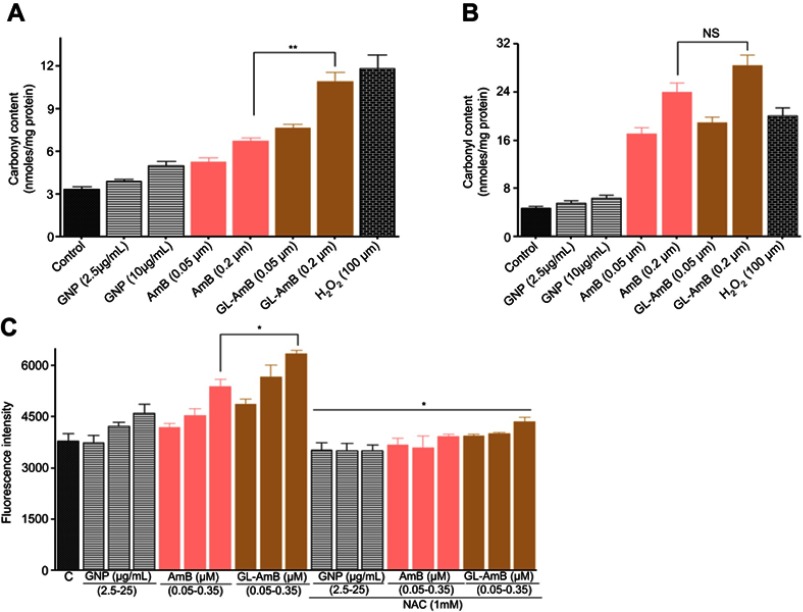

Measurement of protein carbonylation by spectrophotometric assay

AmB-mediated stress causes oxidative modification of the amino acids of proteins to carbonyl groups which were derivatized with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) and then measured by spectrophotometric assay.61 Briefly, promastigotes (1×107 cells/ml) were treated with GNP (2.5 and 10 μg/ml), AmB/GL-AmB (0.05 and 0.2 μM) for 6 and 12 h. Cells were then harvested, lysed and protein carbonylation content was measured as described.62

Lipid peroxidation assay

Parasites (5×106 cells/well) were taken in 24 wells plate and treated with different concentrations of GNP (2.5, 10 and 25 µg/ml), AmB/GL-AmB (0.05-0.35 µM) for 12 h. In parallel, treated cells were also incubated with ROS inhibitor, NAC (1mM). Untreated cells were taken as negative control. Lipid peroxidation products were measured as described.51

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was done by one-way and two-way ANOVA using Graphpad Prism software (version 5.00; GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The results were measured as mean±SD of at least three independent experiments. The results were shown as approximate mean values. Differences between group data (specially between AmB and GL-AmB) were considered statistically significant and highly significant when P<0.05 and P<0.001, respectively.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of GL-AmB conjugate

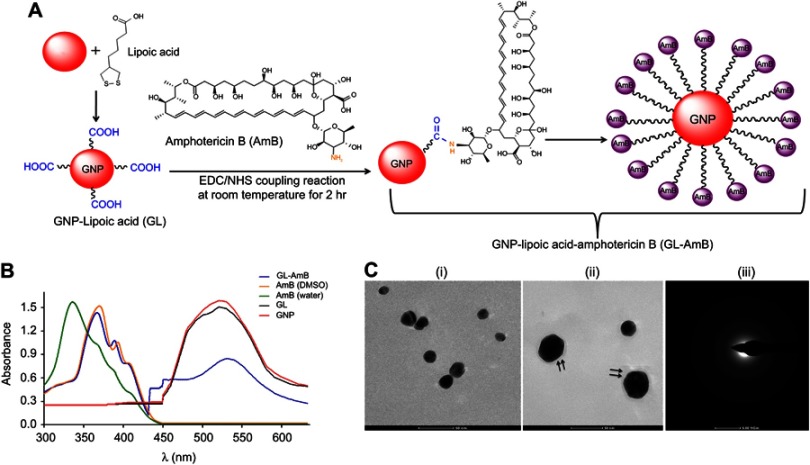

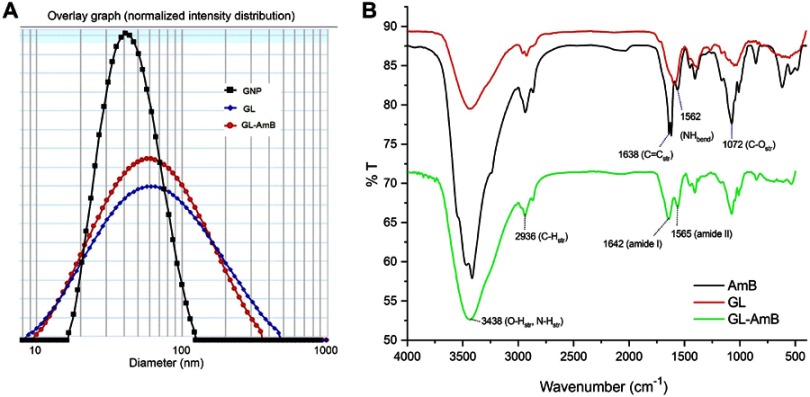

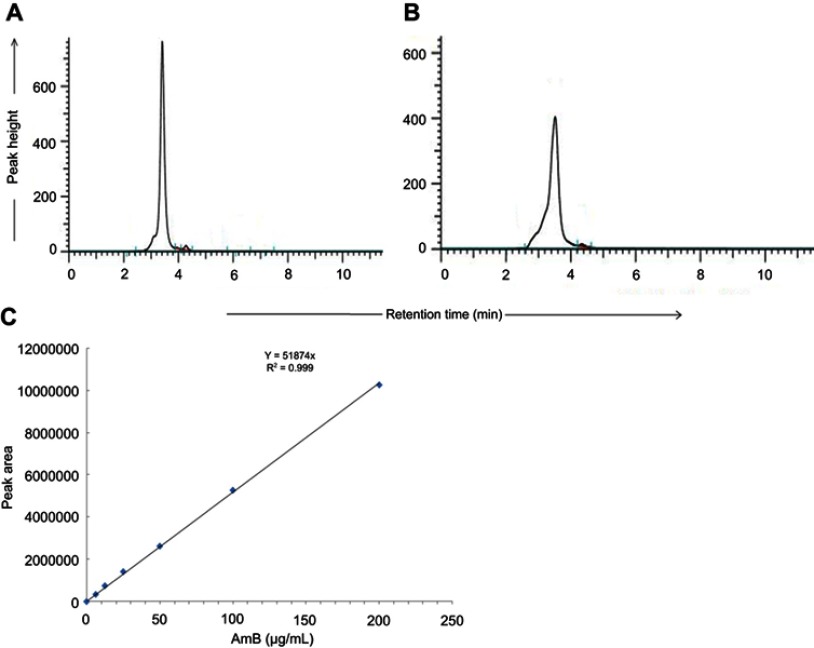

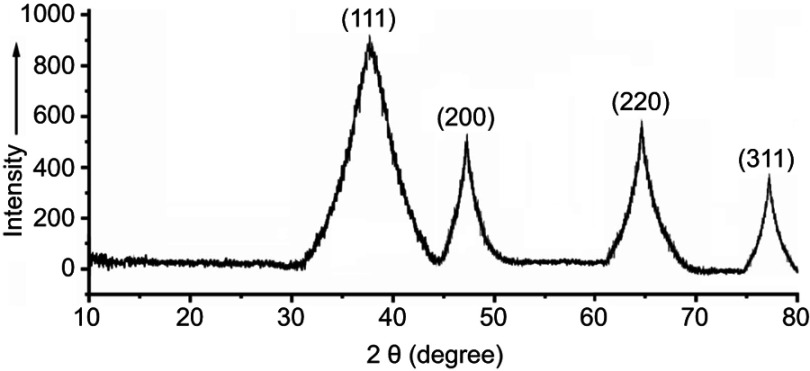

By HPLC measurement, the amount of AmB detected in GL-AmB was ~3.9 mg/mL (~4.23 mM, AmB input was 5 mg/mL) which is equivalent to ~78% conjugation efficiency (compare Figure S1A and B) based on the AmB standard curve (Figure S1C). This data correlated well with the measured ~84% conjugation efficiency by UV spectroscopy (data not shown). Therefore, there is conjugation of ~16 μg of AmB per microgram of Au, indicating multimolecular association of AmB with a single molecule of Au NP (Figure 1A). For schematic presentation, 16 molecules of AmB in conjugation with 1 GNP are shown in Figure 1A, although the exact molar ratio of AmB:GNP in GL-AmB is unknown. The UV absorption spectrum of monomeric AmB is characterized by four bands with peaks around 344–350 (peak I), 363–368, 383–388, and 406–412 nm (peak IV). The ratio between the absorbance intensities of peak I and peak IV was used to measure the degree of aggregation of AmB.63 The higher the ratio of peak I/IV, the higher the degree of aggregation. UV spectra of GL-AmB showed peaks for both AmB (340–410 nm) and GNP (~530 nm), but the intensity of peak I was greatly reduced and the intensity for peak IV was increased. In fact, the AmB-specific peaks of GL-AmB were very similar to AmB dissolved in DMSO, a monomeric disaggregated form of AmB (Figure 1B). Hence, in GL-AmB, AmB becomes aggregation free and water soluble. Further, TEM images confirmed the monomeric and spherical size of GL-AmB (Figure 1C, i and ii) and the visible presence of an AmB layer on GL-AmB (indicated by double arrow in Figure 1C, ii). The selected area electron diffraction pattern confirmed the presence of GNP in GL-AmB (Figure 1C, iii). An increase in hydrodynamic radii of the GNP was observed after its capping with LA to form GL (~46 nm, Figure 2A). However, further conjugation of GL with AmB did not change the hydrodynamic radii appreciably (GL-AmB ~48 nm). Interestingly, the PDI decreased after functionalization of GL with AmB, indicating a narrower size distribution due to further stabilization of NPs by AmB (Figure S2B). Increased negative zeta potential of GL-AmB (−21.16 mV, Figure S2A) compared to GNP (−13.94 mV) indicated the formation of a stable entity with less chance of agglomeration. Conjugation of AmB with GL was further confirmed by FT-IR analysis (Figure 2B). In GL-AmB, IR peaks at 1642 cm−1 for C=O stretching (amide I) and at 1565 cm−1 for N–H bending (amide II), along with the presence of other characteristic peaks of AmB, confirmed successful amide bond formation between the –COOH group of GL and the –NH2 group of AmB. GL-AmB was also examined through pXRD measurement (Figure S3). This revealed Bragg’s diffraction at 38.2°, 47.7°, 65.3°, and 77.1° which were attributed to (111), (200), (220), and (311) sets of lattice planes reflecting the face centered cubic structure of metallic gold.48 The pXRD pattern thus unveiled the crystalline nature of GNP in GL-AmB.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of synthesis of GL and GL-AmB by EDC–NHS coupling (A). Ultraviolet spectra of nanoparticles and AmB (2 mg/mL) in H2O and DMSO (B). TEM image of GNP (C, i) and GL-AmB (C, ii). Double arrow indicates the visible layer of AmB on GNP. Selected area electron diffraction pattern indicating presence of GNP in GL-AmB (C, iii).

Abbreviations: EDC, 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide; GNP, gold nanoparticle; NHS, sulfo-N-hydroxy succinamide.

Figure 2.

Characterization of nanoparticles by dynamic light scattering (A). Fourier transform infrared spectrscopy analysis of GNP, AmB, and GL-AmB (B). Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; GL, GNP-lipoic acid product; GNP, gold nanoparticle.

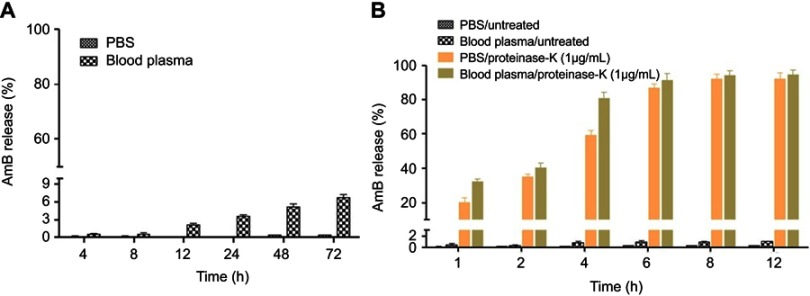

Stability of GL-AmB conjugates

AmB forms a single amide bond with LA in GL to give GL-AmB. Therefore, the stability of GL-AmB is dependent on the stability of this amide bond. We measured stability of GL-AmB by AmB release assay in PBS/plasma after measuring UV spectra at 360 nm since AmB gives the strongest peak at 360 nm. A similar kind of release assay was done earlier for polyethylene glycol-AmB conjugate.49 This is possible because the molar extinction coefficient of AmB is very high64 and, therefore, gives high sensitivity in detection. We tested the stability of GL-AmB by AmB release in the presence and absence of proteinase K, known for its high protease activity with a specificity for cleaving peptide bonds, in PBS and in blood plasma at pH 7.4. In the absence of proteinase K, after 72 h of incubation <7% AmB was detected in plasma (Figure 3A) and <1% AmB was detected in PBS. Interestingly, treatment of GL-AmB with proteinase K released >20% and >60% AmB within 1 and 4 h, respectively, indicating, further, the presence of a stable amide bond in GL-AmB (Figure 3B). However, no significant increase in AmB release was found after 6 h.

Figure 3.

Amount of AmB released from GL-AmB (0.1 mM) was measured by UV absorbance after incubation in PBS and in blood plasma for 48 h (A). Amount of AmB released from GL-AmB (0.1 mM) after incubation in PBS/blood plasma with or without proteinase K (1 μg/mL) for 6 h (B). Data presented in % scale where UV absorbance of 0.1 mM AmB was considered 100%.

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; GL, GNP-lipoic acid product; GNP, gold nanoparticle; UV, ultraviolet.

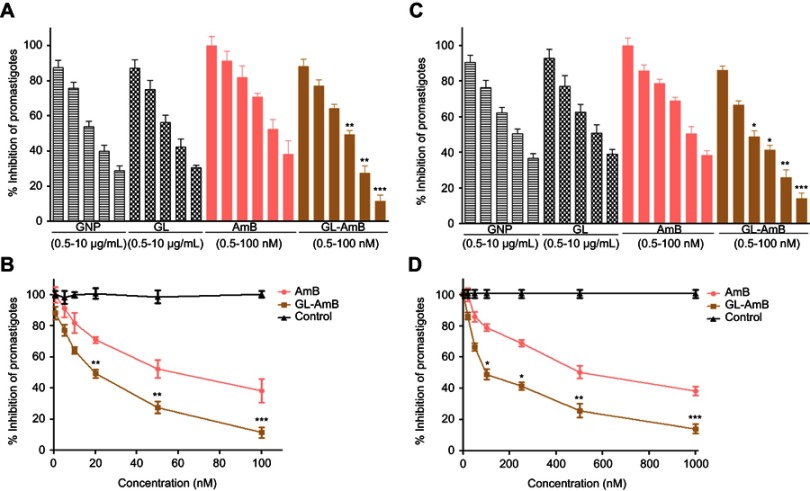

Antileishmanial activity against promastigote and amastigote forms of L. donovani

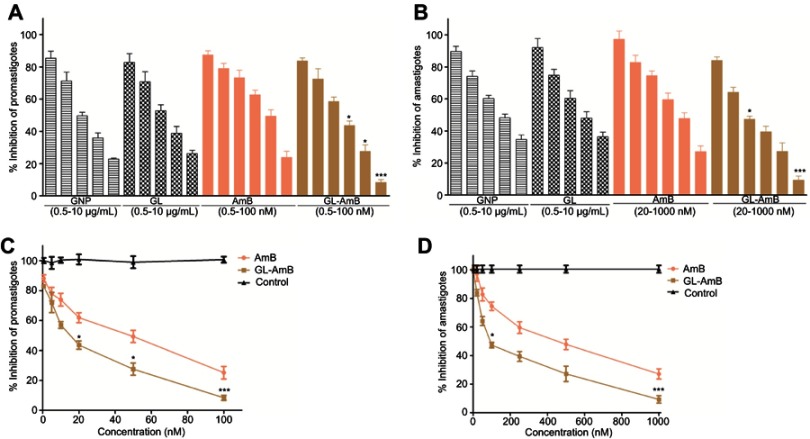

The IC50 for GNP and GL after 48 h was ~2.5 μg/mL against promastigotes (Figure 4A) and ~5 μg/mL against amastigotes (Figure 4B). GL-AmB (IC50~20 nM) showed increased antileishmanial efficacy compared with AmB (IC50~50 nM) against promastigotes at all indicated doses (Figure 4A and B). The IC50 after 48 h for GL-AmB (~100 nM) was five times lower than for AmB (~500 nM, Figure 4C and D) against amastigotes. Therefore, conjugate GL-AmB is more potent than AmB and the presence of linker in the GNP has no effect on improved efficacy. Mere addition of GNP (0.53 pg/mL) and AmB (20 nM) (equivalent to the amount present in 20 nM GL-AmB) in the promastigote assay showed an effect similar to naked AmB in antileishmanial efficacy (data not shown). So, efficacy of GL-AmB against LD is due to the presence of multimolecular AmB conjugated with GNP. The IC50 for GL-AmB against promastigotes after 72 and 96 h was ~18 and ~17 µM, respectively. For AmB, IC50 after 72 and 96 h was ~50 and ~53 µM, respectively, at similar time points. With 20 and 50 nM doses of AmB, survival of promastigotes after 72 h (61% and 50%, Figure S4C) and 96 h (63% and 54%, Figure S5C) shows no significant change with killing efficacy compared to 48 h (71% and 51%, Figure 4B). For GL-AmB with similar doses, survival of promastigotes after 72 h (44% and 27%) and 96 h (41% and 29%) shows, also, insignificant change in killing efficacy compared to 48 h (50% and 27%). However, at every time point, GL-AmB is more efficacious than AmB. For amastigotes, very similar patterns were observed. Therefore, antileishmanial activity data for promastigotes/amastigotes after 72 h and 96 h showed no significant change in killing efficacy with increasing dose (Figure S4 and S5). This is likely because AmB is only stable for 3 days in cell culture medium, as suggested by different manufacturers.

Figure 4.

Activity of nanoparticles and AmB after 48 h treatment against Leishmania donovani promastigotes in vitro (A) and against intracellular amastigotes ex vivo (C). Comparative efficacy for AmB and GL-AmB against promastigotes (C) and amastigotes (D).

Note: *P<0.05; **0.05<P<0.01; ***0.01<P<0.001.

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; GL, GNP-lipoic acid product; GNP, gold nanoparticle.

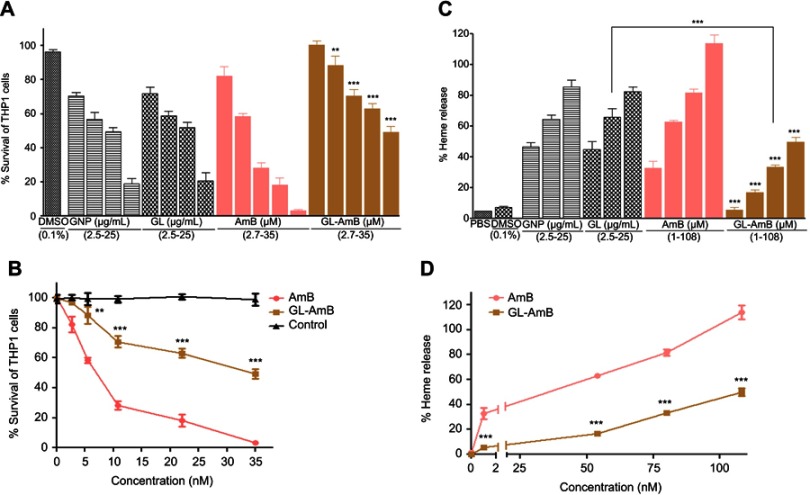

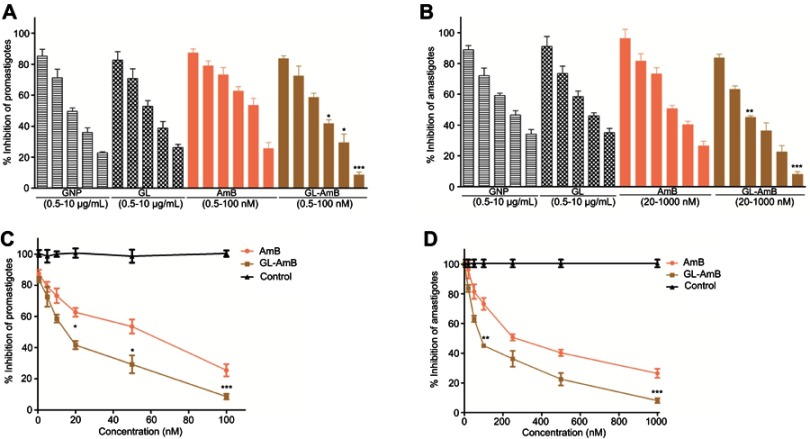

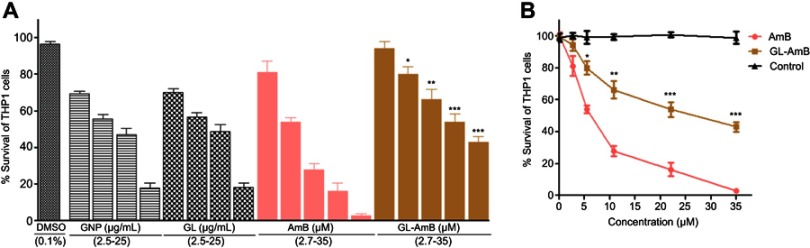

Cytotoxicity and hemolytic studies

For GNP and GL, the concentration showing 50% killing of macrophages compared to untreated control after 48 h (CC50 value) was ~10 μg/mL. For AmB and GL-AmB, the CC50 values were ~8 and ~35 μM, respectively. At an 11 μM dose (~22 times IC50 of AmB on amastigotes), AmB and GL-AmB showed ~28% and ~70% survival of THP-1 cells (P<0.001, Figure 5A and B). When THP-1 cells were treated with 22 µM of AmB and GL-AmB, survival was ~18% and ~63%, respectively. After 72 h with a 35 µM dose, THP-1 survival was ~2% for AmB-treated cells but ~44% for GL-AmB-treated cells (Figure S6). Therefore, GL-AmB is significantly less cytotoxic than AmB (P<0.001) and this was due to conjugation of AmB over GNPs and not due to the presence of linker in GNPs.

Figure 5.

Cytotoxicity assay on THP-1 cells after 48 h treatment with nanoparticles and AmB (A). Hemolysis assay on human red blood cells after 4 h treatment with nanoparticles and AmB (C). DMSO (0.1%) used as negative control. Comparative efficacy of AmB and GL-AmB in cytotoxicity (B) and hemolysis (D) assay.

Note: **0.05<P<0.01; ***0.01<P<0.001.

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; GL, GNP-lipoic acid product; GNP, gold nanoparticle.

Both, GNPs and GL showed very similar and high hemolytic activity. At 2.5 μg/mL, >40% hemolysis is observed with GNP/GL. At a 1 μM dose, AmB showed ~32% hemolysis but GL-AmB showed only ~5% hemolysis (P<0.001, Figure 5C and D). Hemolysis was ~63% and ~83% at 54 µM and 80 µM doses of AmB. Under similar conditions, hemolysis for GL-AmB-treated erythrocytes was ~17% and ~33% (Figure 5D, P<0.001). At the highest tested dose (108 μM), GL-AmB showed significantly reduced hemolysis compared to AmB (48% vs 112%). Therefore, hemolytic activity of both GNPs and AmB was significantly reduced due to conjugation of AmB with GNP.

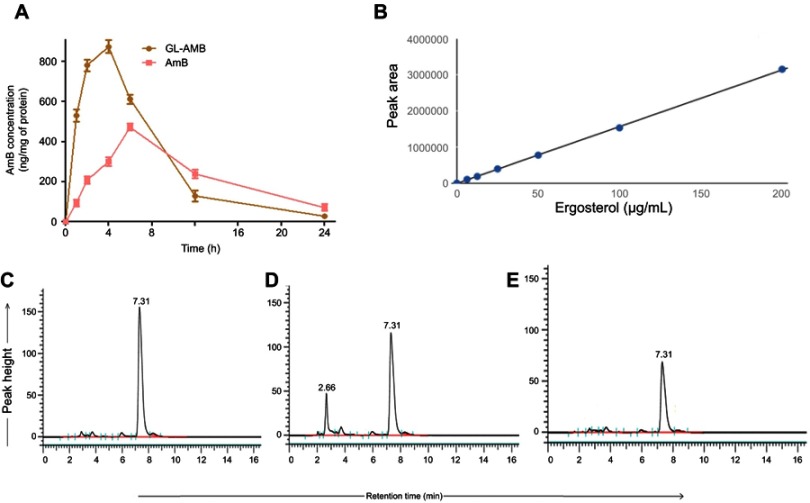

AmB and ergosterol determination by HPLC

Macrophages were treated with a high dose of AmB/GL-AmB (300 μg/mL/106 macrophages) for 1–24 h to see the difference in AmB uptake, if any, between AmB and GL-AmB. After 1, 2, and 4 h, AmB uptake was significantly higher for GL-AmB-treated cells than for AmB-treated cells as measured by HPLC (represented as nanograms of AmB/milligrams of protein, Figure 6A). AmB uptake was ~5.5-fold (~560 vs ~95), ~3.7-fold (~780 vs ~209), and ~2.9-fold (~875 vs ~311) higher for GL-AmB-treated cells compared to AmB-treated cells after 1, 2, and 4 h of treatment, respectively (P<0.001, Figure 6A). AmB uptake was reduced to ~1.3-fold after 6 h (~612 vs 472 for GL-AmB and AmB, respectively), possibly due to high AmB-mediated toxicity leading to reduced macrophage uptake. Consequently, the difference in AmB uptake was less significant between GL-AmB and AmB-treated cells after 12 and 24 h of treatment.

Figure 6.

Macrophage uptake of AmB as measured by HPLC (A). Ergosterol standard curve for HPLC (B) and measurement of ergosterol content in parasites either untreated (C) or treated with AmB (D) and GL-AmB (E).

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; HPLC, high pressure liquid chromatography; GL, GNP-lipoic acid product; GNP, gold nanoparticle.

AmB binds ERG with higher efficacy than cholesterol35 and AmB-resistant LD parasites are associated with changes in gene expression or mutation in genes involved in the ERG biosynthesis pathway.65,66 The ERG content of samples were measured based on the ERG standard curve with a retention time (RT) of 7.31 min in HPLC (Figure 6B). The ERG content was ~1.9-fold lower in GL-AmB-treated cells compared to AmB-treated cells (34.2 μg/mL vs 65.1 μg/mL, Figure 6D and E) and ~3.4-fold lower compared to untreated cells (116.4 μg/mL, Figure 6C). The peak with RT of 2.66 min (Figure 6D) was possibly due to sterol, cholesta-5,7,24-triene-3β-ol, which was the major sterol in the AmB-resistant LD strain due to inhibition of enzyme SCMT (S-adenosyl-l-methionine:C-24-∆-sterol methyltransferase) and consequent lack of C-24 transmethylation of C-27 sterols.66

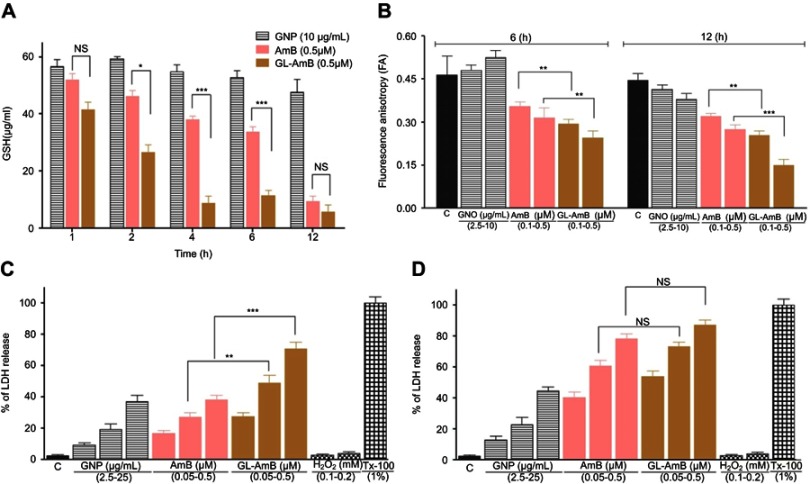

Determination of thiol content

After 2, 4, and 6 h, the GSH content in GL-AmB-treated (0.5 μM) parasites was ~1.7, ~5 and ~3-fold lower (P<0.001) compared to AmB-treated parasites, respectively (Figure 7A). However, the reduction in GSH content becomes insignificant after 12 h.

Figure 7.

Treatment of parasites with nanoparticles and AmB followed by measurement of GSH (A), determination of fluorescence anisotropy values of DPH-labelled parasites (B), and measurement of membrane leakage by LDH assay after 6 h(C) and 12 h (D). 1% Triton-X-100- (Tx-100)-treated and H2O2-treated (0.1–0.2 mM) cells were used as positive and apoptotic controls, respectively.

Note: *P<0.05; **0.05<P<0.01; ***0.01<P<0.001.

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; DPH, diphenyl hexatriene; GL, GNP-lipoic acid product; GNP, gold nanoparticle; GSH, reduced glutathione; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; HPLC, high pressure liquid chromatography; NS, non-significant.

Fluorescence anisotropy by DPH assay

The FA value of GL-AmB-treated (0.5 μM) parasites was ~1.3 (P<0.01) and ~1.8 times (P<0.001) lower (Figure 7B) than that of AmB-treated parasites after 6 and 12 h, respectively. The membrane of GL-AmB-treated cells was, therefore, more fluidic than that of AmB-treated cells.

Measurement of membrane leakage by LDH assay

Increased membrane damage, leading to necrosis, is associated with extracellular release of LDH. At 0.5 μM concentration, LDH release was ~71% and ~38% after 6 h for GL-AmB and AmB-treated cells, respectively (Figure 7C, P<0.001). Interestingly, after 12 h under similar treatment conditions, the difference in LDH release is insignificant (78% and 87% for AmB and GL-AmB, respectively, Figure 7D). GNP at 25 μg/mL concentration showed ~37% LDH release. Upon treatment with H2O2, which causes apoptosis, the amount of LDH release was <4%. So, GL-AmB is more necrotic than AmB against LD.

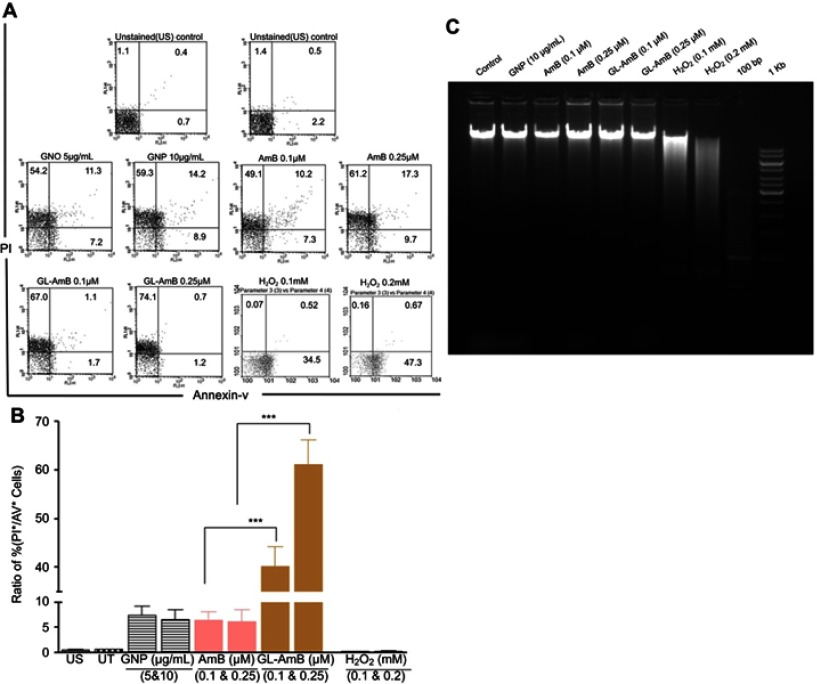

FACS analysis and DNA fragmentation assay

A necrotic or apoptotic mode of cell death was observed in LD after treatment with AmB and AmB formulations.51,67 In FACS analysis, the percentage of PI+ and AV+ promastigotes was taken as necrotic and apoptotic cells, respectively. Therefore, the increase in the ratio of percentage of PI+/AV+ cells was an indicator of increased necrosis. The ratio was ~61 for GL-AmB and ~7 for AmB (Figure 8C, P<0.001) when parasites were treated with 0.5 µM of AmB/GL-AmB. At the 0.25 µM treatment condition, the ratio was ~40 and ~6 for GL-AmB and AmB, respectively. Hence, GL-AmB-mediated parasite death is more necrotic than apoptotic (Figure 8A). Further, no significant DNA laddering were observed in AmB and GL-AmB-treated samples (0.05 and 0.15 μM), confirming the absence of apoptosis under these conditions where H2O2-treated cells, used as apoptotic control,59 showed significant DNA laddering as expected (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

FACS analysis of AV and PI-stained promastigotes after treatment with nanoparticles and AmB (A). H2O2-treated (0.1–0.2 mM) cells were used as apoptotic control. Representation of FACS data as a ratio of (%) of (PI+/AV+ cells) under similar treatment conditions (B). Agarose (1.5%) gel electrophoresis of genomic DNA isolated from parasites treated with nanoparticles, AmB, and H2O2 with 100 bp and 1 Kb DNA ladder as marker (C).

Note: ***P<0.001.

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; AV, Annexin V-FITC; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; GL, GNP-lipoic acid product; GNP, gold nanoparticle; PI, propidium iodide.

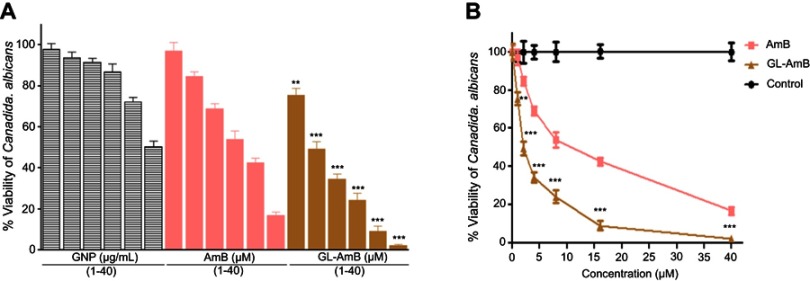

In vitro activity against C. albicans

Against C. albicans, IC50 of GL-AmB and AmB was ~2 μM and ~8 μM, respectively indicating ~4-fold improvement in antifungal efficacy (Figure S7). The IC50 of citrate-reduced GNP was found to be ~40 μg/ml. Therefore, GL-AmB is more efficacious than AmB against, both, parasites and fungus.

Protein carbonylation assay

Protein carbonylation, which is a measure of oxidative stress-mediated damage caused by AmB, was higher in GL-AmB-treated cells after 6 h but almost similar after 12 h (Figure S5B) compared to AmB-treated cells. After 6 h of treatment, protein carbonylation was ~1.7 fold more for GL-AmB than AmB-treated parasites (Figure S5A). The amount of protein carbonylation caused by GL-AmB was almost comparable to 100 μM H2O2-treated cells after 6 h.

Lipid peroxidation measurements

High levels of free radicals or ROS can inflict direct damage to lipids specially to polyunsaturated fatty acids. It generates high levels of lipid peroxyl radicals and hydroperoxides which causes cell death by apoptotic or necrotic mode.62 Lipid peroxidation products were higher in GL-AmB-treated cells than AmB-treated cells at all indicated doses (P < 0.05, Figure S5C).

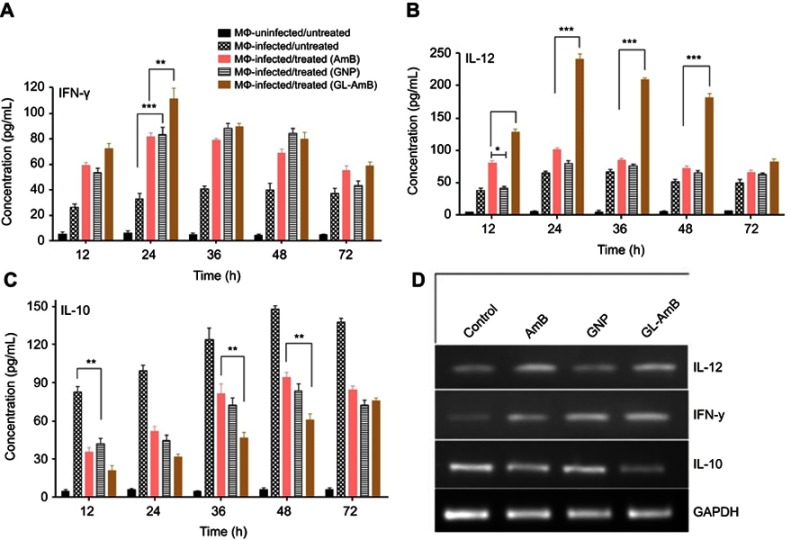

Cytokine analysis by ELISA and semiquantitative PCR

Stimulation of Th1-cell-associated immune responses, mediated by IL-12 and IFN-γ, enhanced the antileishmanial effect of AmB in LD-infected animals.30,68 Significant up-regulation in the levels of Th1 (IL-12 and INF-γ) and down-regulation of Th2 (IL-10) cytokines were observed after GNP, AmB, and GL-AmB treatment in LD-infected macrophages compared to untreated control. After 12 and 24 h, GL-AmB showed ~2.7 and ~3.4-fold elevation of the IFN-γ level (P<0.001) compared to untreated control (Figure 9A). Under similar conditions, AmB-treated macrophages showed ~2.2 and ~2.5-fold increase in IFN-γ level. However, elevation of the IFN-γ level reduced to ~2 and ~1.6-fold after 48 and 72 h, respectively, for GL-AmB-treated cells compared to untreated control. The level of IL-12 was ~3.4 and ~3.7-fold increased for GL-AmB whereas for AmB the elevation was ~2.1 and ~1.6-fold after 12 and 24 h, respectively, compared to untreated control (Figure 9B). IL-12 release was significantly higher for GL-AmB-treated cells compared to untreated control even after 36 h (~3.1-fold) and 48 h (~3.5-fold). Under similar conditions, the level of IL-12 release was ~1.25 and ~1.4-fold for AmB-treated cells compared to untreated control. Further, the decrease in IL-10 cytokine level was more significant for GL-AmB-treated than for AmB-treated macrophages after 12 h (~3.9 vs ~2.3-fold), 24 h (~1.9 vs ~3.1-fold), 36 h (~2.6 vs 1.5-fold), and 48 h (~2.4 vs 1.5-fold) (Figure 9C). Therefore, GL-AmB caused more immunostimulatory effect than AmB by increasing the Th1 and decreasing the Th2 cytokine levels significantly. Interestingly, citrate-reduced GNP also significantly increased the level of Th1 (~2.0 and ~2.5-fold higher IFN-γ after 12 and 24 h, respectively) and decreased the level of Th2 cytokine (~2.0 and ~2.2-fold reduced IL-10 after 12 and 24 h, respectively) compared to untreated control. The change in macrophage cytokine level after GL-AmB/AmB treatment was also confirmed by semiquantitative PCR of genes specific for Th1 and Th2 cytokines. The IFN-γ level was ~3.2 and ~1.9-fold up-regulated in GL-AmB and AmB-treated cells, respectively, compared to untreated control (Figure 9D, Table 1). For IL-12, the up-regulation was ~2.5 and ~2.0-fold under the same conditions. For IL-10, the mRNA level was down-regulated by ~2.3 and ~1.7-fold in GL-AmB and AmB-treated cells, respectively, compared to untreated control. Therefore, mRNA expression levels of Th1 and Th2 cytokines showed patterns similar to cytokine ELISA of GL-AmB and AmB-treated macrophages. For GNP, we found ~2.4-fold up-regulation of IFN-γ but no significant change in IL-12 mRNA level compared to untreated control (Figure 9D).

Figure 9.

Macrophages were treated with nanoparticles and AmB for 6 h followed by cytokine ELISA for IFN-γ (A), IL-12 (B), and IL-10 (C). Semiquantitative PCR for genes specific for macrophage IFN-γ, IL-12, IL-10, and GAPDH (D).

Note: *P<0.05; **0.05<P<0.01; ***0.01<P<0.001.

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; GL, GNP-lipoic acid product; GNP, gold nanoparticle; IFN-γ, interferon-γ.

Table 1.

List of primers used in semiquantitative PCR

| Target gene | Product length (bp) | Primer sequence (5ʹ–3ʹ) | Annealing temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LD trypanothione reductase (TryR) | 220 | Forward: TGGAACGCGG CCGTCACGCA | 62 |

| Reverse: TCTTCCAGTTGGGGCAGAGC | |||

| LD superoxide dismutase (SOD) | 200 | Forward: GAGTTCCGCAACCGTTCCGG | 58 |

| Reverse: TAGTGCACGCGAATCTGGTA | |||

| LD ascorbate peroxidase (APX) | 220 | Forward: ATCCGGGCTCTCCGCGCCGA | 62 |

| Reverse: GCCTTGCGAGGGATGTCGAG | |||

| LD sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) | 200 | Forward: CACCATGAACATCTGCGGCA | 60 |

| Reverse: TCAGCTCCTCGGCCAGGAAG | |||

|

S-adenosyl-l-methionine-C-24-delta-sterol-methyltransferase (SCMT) |

119 | Forward: GGCGTCAACAACAACGATTAC | 62 |

| Reverse: TTGTCGGCTAAGCTCATGTT | |||

| 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMG CoA reductase) | 150 | Forward: CGTGATCAAGTTCTGTGAGGAG | 58 |

| Reverse: CCCATCGCATCTCCAGTAAAG | |||

| LD α-tubulin | 220 | Forward: TCGACAATGAGGCCATCTAC | 60 |

| Reverse: GACACCACCGGAGCATAGCT | |||

| LD arginase 1 | 230 | Forward: AAATGAGCATTGTGCTGGCG | 57 |

| Reverse: GGTGCATTCCGCGGTCAGGC | |||

| LD HSP70 | 220 | Forward: TGGCAGAACGAACGCGTGGA | 55 |

| Reverse: CCTTGAACGGCCAGTGCTTC | |||

| Mouse iNOS | 128 | Forward: AGGAGGAGAGAGATCCGATTTAG | 58 |

| Reverse: TCAGACTTCCCTGTCTCAGTAG | |||

| Mouse IFN-γ | 230 | Forward: ATGAACGCTACACACTGCAT | 58 |

| Reverse: AGTCTGAGGTAGAAAGAGAT | |||

| Mouse IL-12 | 220 | Forward: TGGAACTACACAAGAACGAGAG | 60 |

| Reverse: ACCAGCATGCCCTTGTCTAG | |||

| Mouse IL-10 | 230 | Forward: ATGCCTGGCTCAGCACTGCT | 56 |

| Reverse: TAACCCTTAAAGTCCTGCAT | |||

| Mouse GAPDH | 220 | Forward: TGCATCCTGCACCACCAACT | 60 |

| Reverse: TGGGATGACCTTGCCCACAG |

Abbreviations: HSP, heat shock protein; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; LD, Leishmania donovani.

Discussion

Discovery of new liposomal AmB formulations23 reduces the cytotoxicity of AmB but comes with limitations of a narrow therapeutic index or high cost for lipid formulations.69 AmBisome contains a liposomal membrane consisting of hydrogenated soy phosphatidylcholine, cholesterol, and distearoylphosphatidylglycerol along with other ingredients. Due to the presence of these costly lipid molecules, the cost of AmBisome formulation becomes very high and, therefore, a main barrier to widespread use in the pharmacotherapy of leishmaniasis in developing countries.24,70 In fact, to check the feasibility of cost reduction in VL treatment, a single-dose liposomal AmB was compared with 15 alternate-day infusions of amphotericin B deoxycholate in a clinical trial.71 Therefore, water-stable and well-dispersed aqueous solutions of AmB with low toxicity and reduced manufacturing costs remain a priority. New derivatives of AmB for improved water solubility, antifungal efficacy, and reduced cytotoxicity were synthesized.52,72–74 In general, the single amine and single carboxylic group of AmB were preferred for chemical modification75,76 where modification of the AmB amine group was found to be more effective in reducing the cytotoxicity77 without compromising efficacy52 against fungus.

GNP was functionalized with a linker LA to chemically conjugate the amine group of AmB with the carboxylic group of LA to produce GL-AmB (Figure 1A). The conjugate became water soluble (~5 mg/mL). UV spectroscopy of GL-AmB is very similar to a DMSO-soluble nonaggregated form of AmB (Figure 1B), indicating the mono-disperse nature of GL-AmB further confirmed by TEM analysis (Figure 1C) and observed higher negative zeta potential values (Figure S2) of GL-AmB compared to AmB. The IC50 for GL-AmBcompared to AmB was ~5-fold reduced (~100 nM vs ~500 nM) against amastigotes (Figure 4D). Apart from its efficacy against LD (~2.5-fold reduction in IC50 against promastigotes, Figure 4C), GL-AmB was, also, found to be more potent than AmB against fungus Candida albicans (~4-fold reduction in IC50, Figure S7) in vitro. However, there is no significant change in killing efficacy for promastigotes or amastigotes after 48 h with increasing doses, possibly due to instability of AmB in cell culture medium after 72 h. HPLC analysis showed increased macrophage uptake for GL-AmB (>5, >3.5, and >2.5-fold after 1, 2, and 4 h, respectively, Figure 6A) compared to standard AmB. Macrophage uptake of AmB/AmB formulation up to 24 h was also done earlier with human monocyte cells THP-155 and human macrophages J774,72 where uptake of different AmB formulations was clearly shown with significant differences. Macrophage uptake correlates well with the TEM image of polyphenol-functionalized GNPs' fast uptake in macrophages,48 indicating a possible advantage of GNP-based drug delivery in VL, a disease where the parasite primarily infects the macrophages of the liver and spleen. The RT of AmB and GL-AmB was 3.41 and 3.52 min, respectively, in HPLC (Figure S1A and B) and, therefore, the peak of AmB obtained (RT=3.44 min) during macrophage uptake studies for GL-AmB could be due to a mixture of free AmB (released after cleavage of amide bond by macrophage peptidases78) and AmB present in intact GL-AmB. For GNP, the CC50 against THP-1 cells was ~10 μg/mL, which was just 2 times its IC50 on amastigotes. This explains, possibly, why citrate-reduced GNPs are not reported as effective antileishmanial agents although green-synthesized GNPs show promise for the same.48,79,80 Observed cytotoxicity of GNPs depends on the size, surface chemistry, and type of cell where it was used.81 The mechanism of cytotoxicity arising for citrate-reduced GNPs is not yet established but studies have shown that increased sodium citrate on the surface of GNPs was more cytotoxic for alveolar epithelial cell lines.82 Oxidative stress-mediated toxicity was reported for citrate-reduced GNP-induced release of nitric oxide into serum.83 GNPs coated with citrate have shown increased internalization in macrophages with decreased glutathione level.84 So, it is likely that change in redox homeostasis and binding of serum proteins85 causes cytotoxicity of citrate-reduced GNPs against macrophages.

Reduced GSH, a potent antioxidant which controls cellular redox status, was significantly lower in GL-AmB-treated cells after 4 and 6 h (~5 and ~3-fold lower, respectively) compared to AmB-treated cells (P<0.001, Figure 7A). However, this reduction was nonsignificant after 12 h (~1.6-fold) of treatment, indicating, again, higher early uptake of AmB in promastigotes after GL-AmB treatment (Figure 7A). This observation was also consistent with the measured difference in protein carbonylation which is a measure of oxidative stress-mediated damage caused by AmB.50 Protein carbonylation was higher in GL-AmB-treated cells after 6 h (~1.6-fold) but almost similar after 12 h (<1.2-fold) compared to AmB-treated cells (Figure S9A and B). Similarly, the increase in ROS (Figure S8A) and lipid peroxidation products (Figure S9C), which can be abrogated by pretreatment with ROS scavenger NAC, were significantly higher in GL-AmB-treated than AmB-treated cells after 6 h. Due to high similarity in observed results of GL-treated and GNP-treated samples, in most cases, the results for GL-treated samples were omitted.

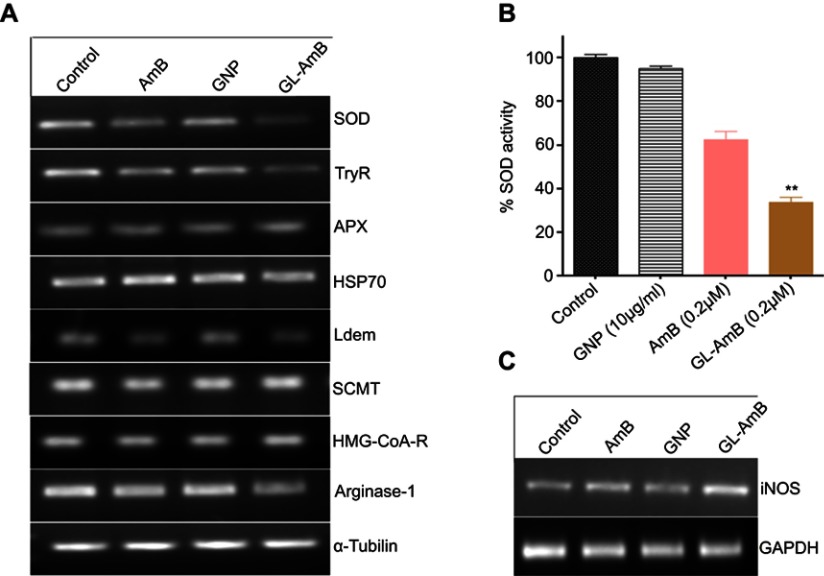

Trypanathione reductase (TryR) is involved in biosynthesis of trypanathione (major thiol of Leishmania along with glutathione) and maintaining the reduced status of LD under oxidative stress. The relative mRNA level of TryR and superoxide dismutase (SOD) were significantly lower (Figure S10A) and SOD enzyme activity was also reduced in GL-AmB-treated cells compared to AmB-treated cells (Figure S10B). We found ~3.1 and ~2.1-fold reduction in the TryR mRNA level for GL-AmB and AmB-treated promastigotes, respectively. Treatment of GNPs also showed ~1.8-fold reduction in TryR expression which is consistent with the observation that the amount of ROS produced by GNPs and AmB-treated cells is comparable (Figure S8A). Interestingly, selected gold complexes have earlier shown potential as antileishmanial agents by targeting trypanathione reductase.86 For SOD, the reduction in mRNA level for GL-AmB and AmB-treated cells was ~2.63 and ~1.8-fold, respectively (Figure S10B). Consistent with observed higher reactive nitrogen species in GL-AmB-treated cells (Figure S8B), inducible nitric oxide synthase expression was also ~2.85 and ~1.75-fold up-regulated (Figure S10C) in GL-AmB and AmB-treated amastigotes, respectively. Expression of ascorbate peroxidase (APX) in AmB-resistant LD strain87 and expression of heat shock protein (HSP-70) in human epithelial cells after AmB-conjugated NP treatment88 were found to be elevated. However, no significant changes were observed for APX and HSP-70 mRNA expression level after GL-AmB/AmB treatments compared to untreated control. The expression level of lanosterol-14-α-demethylase (Ldem) mRNA was ~2.1 and ~1.6-fold reduced in GL-AmB and AmB-treated cells, respectively. However, the expression level of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase mRNA, which is related to mevalonate biosynthesis and not directly related to ERG biosynthesis, was unchanged under similar treatment conditions (Figure S10A). The expression level of arginase 1, involved in the polyamine biosynthesis pathway, does not show any change after GL-AmB/AmB treatment compared to untreated control. In short, the difference between the level of ROS, oxidized protein carbonyl, and reduced glutathione content in GL-AmB and AmB-treated cells correlated well with observed changes in mRNA expression for genes involved in the oxidative stress response and ERG biosynthesis pathway of LD (Figure S10A). This shows that GL-AmB and AmB kills parasites through a common mechanism of action involving oxidative stress and the ERG biosynthesis pathway.

There was a marked increase in LDH release (Figure 7C) consistent with increased membrane fluidity (Figure 7B) in GL-AmB-treated parasites. This is a pattern similar to necrosis. Similarly, an increase in PI+ cells with a concomitant decrease in AV+ cells (higher PI+/AV+ ratio in Figure 8C) and lack of fragmented DNA (Figure 8B) indicated an enhanced necrotic mode of death of LD after GL-AmB treatment compared to AmB treatment. Interestingly, the ratio of PI+/AV+ cells was very similar for GNP and AmB-treated cells, indicating a possible necrotic mode of death induced by citrate-reduced GNPs as well.

VL is known to be associated with a mixed Th1–Th2 cytokine response. AmB-treated patients corresponded with an elevation in Th1 and down-regulation of Th2 cytokines.89 GL-AmB, compared to AmB, significantly increased the level of Th1 (IL-12, IFN-γ) and significantly reduced the level of Th2 (IL-10) cytokines as measured by cytokine ELISA (Figure 9A–C) or by semiquantitative PCR for cytokine mRNAs (Figure 9D). Importantly, the change in released Th1 and Th2 level for GL-AmB-treated cells compared to AmB-treated cells is more significant at earlier time points (ie, 12, 24, and 48 h) and became insignificant after 72 h. Genes specific for Th1 (IFN-γ, IL-12) and Th2 (Il-10) cytokines showed significant changes in expression level between untreated and treated cells. The IFN-γ level was ~3.2 and ~1.9-fold up-regulated in GL-AmB and AmB-treated cells, respectively, compared to untreated control. For IL-12, the up-regulation was ~2.5 and ~2.0-fold under the same conditions. For IL-10, the mRNA level was down-regulated by ~2.3 and ~1.7-fold in GL-AmB and AmB-treated cells, respectively, compared to untreated control. For GNP, we found ~2.4-fold up-regulation of IFN-γ but no significant change in IL-12 mRNA level compared to untreated control. Therefore, semiquantitative PCR data (Figure 9D) correlate well with the cytokine ELISA data (Figure 9A–C).

Conclusion

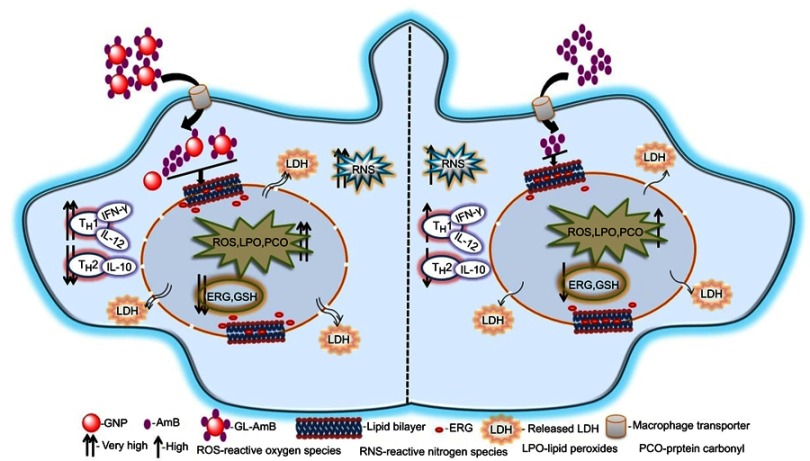

Earlier, our coworkers showed a GNP-based detection method for measuring LD RNA in amastigote-infected macrophages.90 They identified a drug-resistant LD strain based on GNP-based detection of single nucleotide polymorphism associated with resistance.91 In parallel, hemoglobin-guided92 and macrophage membrane-derived93 nanovesicles for AmB delivery were developed for improved antileishmanial efficacy. In this study, efficacy of a synthesized gold nanoparticle–lipoic acid–amphotericin B (GL-AmB) covalent conjugate was evaluated compared to standard AmB against LD promastigote and amastigote forms. GL-AmB showed enhanced AmB uptake inside macrophages leading to higher production of reactive nitrogen species and an increased immunostimulatory effect measured by elevated Th1 and decreased Th2 cytokine levels. GL-AmB caused severe membrane damage leading to necrosis, increased extracellular release of LDH through porous membranes, marked depletion in ergosterol, and reduced thiol content. This is paralleled with higher production of ROS, lipid peroxides, and oxidized protein carbonyls in GL-AmB-treated parasites compared to AmB-treated parasites. In conclusion, the mechanism of action of GL-AmB and AmB are very similar (Figure 10). However, GNP-based formulation of AmB is advantageous due to its enhanced antileishmanial activity, reduced toxicity, high macrophage uptake, increased immunostimulatory effect, and marked depletion in ERG content of parasite membranes leading to increased fluidity. In addition, we have found a possible mechanism of action of citrate-reduced GNP against LD. The high toxicity and hemolytic activity of both citrate-reduced GNP and AmB were significantly reduced following conjugation of AmB with GNP. Therefore, GNP-based formulation of AmB may replace available formulations of AmB in future, and synthesis of new GNP-based conjugates with other antileishmanial or antifungal agents may give us new insights into GNP-based drug delivery.

Figure 10.

Schematic presentation showing mechanism of action with improved efficacy of GL-AmB over AmB in Leishmania donovani.

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; ERG, ergosterol; GL, GNP-lipoic acid product; GNP, gold nanoparticle; GSH, reduced glutathione; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial assistance in research funding to Debabrata Mandal and PhD fellowship to Prakash Kumar, Pragya Prasanna, Saurabh Kumar, and Prasad Surendra Rajit from the Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers, Government of India.

Abbreviation list

GNP, gold nanoparticle; AmB, amphotericin B; LA, lipoic acid; PDI, polydispersity index; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; SAED, selected area electron diffraction; FT-IR, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy; EDC, 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide; NHS, sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinamide; VL, visceral leishmaniasis; LD, Leishmania donovani; ERG, ergosterol; SOD, superoxide dismutase; NAC, N-acetyl l-cysteine; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; RT, retention time.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Supplementary materials

Methods

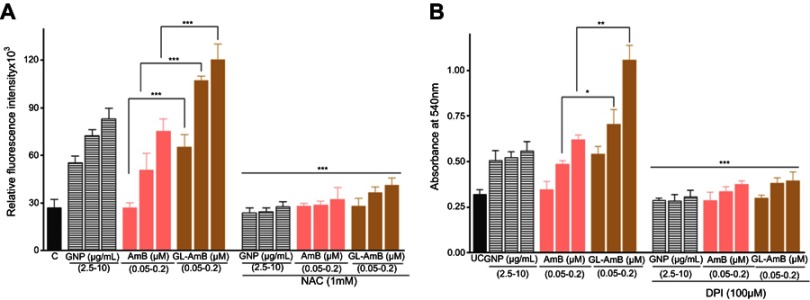

Determination of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in promastigotes by fluorescent dye H2DCFDA

Promastigotes (5×106 cells/ml) were treated with GNP (2.5, 5 and 10 µg/ml), AmB/GL-AmB (0.05-0.2 µM) for 6 and 12 h. Amount of ROS accumulated in promastigotes were measured by fluorescent dye H2DCFDA as described.1

Determination of nitrites from amastigotes by Griess reagent

Reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and nitrites were measured by Griess reagent-based colorimetric assay at 540 nm from amastigote-infected macrophages.2

Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Reverse transcription was performed using 1 μg of total RNA by cDNA synthesis kit (Roche, USA) according to the manufacturer's instruction. The synthesized cDNAs (from RNA of promastigotes) were amplified by PCR for specific genes viz. trypanothione reductase (TryR), superoxide dismutase (SOD), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), heat shock protein-70 (HSP-70), arginase-1, lanosterol-14-demethylase (Ldem), S-adenosyl-L-methionine:C-24-∆-sterol methyltransferase (SCMT), 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMG-CoA-R) and α-tubulin. The synthesized cDNAs (from RNA of amasitogote infected macrophages) were amplified by PCR for specific genes viz. inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), IL-12, IL-10, IFN-γ and GAPDH. LD α-tubulin and macrophage GAPDH were used as loading control for promastigote and macrophage models, respectively. The PCR mixture (25 μl) contains 0.6 μM of forward and reverse primer, 0.5 mM of each dNTP, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μg of synthesized cDNA and 1 μl Taq polymerase. The sequence of PCR primers, annealing temperature and size of PCR products were shown in Table 1. The PCR was done for 28 cycles where each cycle had denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, annealing (ranging from 55-62°C) for 30 sec and extension at 72°C for 45 sec. Samples were preheated at 95°C for 3 min before PCR. The products were run on 1.5% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml), and finally documented and quantified using the gel documentation system and associated Gene-tool software (Syngene, USA).

Isolation of total RNA from promastigotes and amastigote-infected macrophages

Parasites (5×106 cells/well) were treated with GNP (5 μg/ml), AmB/GL-AmB (0.1 μM) for 6 h. Treated cells were centrifuged at 4200g for 10 min, washed thrice with PBS and then total RNA was isolated by addition of TRIZOL solution (Thermo Scientific, USA) as described. Pellet of RNA was air-dried, re-suspended in 100 µL of RNase-free water and treated with DNase I (1U/μl) at 37°C for 30 min. Digested RNA was loaded on RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, USA) columns and RNA was eluted in 30 μl of RNase-free water. RNA quality was checked by gel electrophoresis and quantified by Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo scientific, Nanodrop 2000, USA).

For isolation of RNA from macrophage-infected parasites, RAW 264.1 cells (1×106/well) were grown in a 6 well plate and infected with 1×107 parasites for 12 h. Non-phagocytic cells were washed out, fresh medium was added and then incubated further for 12 h. Parasite-infected macrophages were treated with GNP (10 μg/ml), AmB and GL-AmB (1 μM) for 6 h and then RNA was isolated from the cell pellet as described above.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity assay

Promastigotes (5×106 cells/ml) were treated with GNP (10 μg/ml), AmB/GL-AmB (0.2 μM) for 6 h and then harvested. Cells were lysed and SOD enzyme activity assay was performed as described.3 The enzyme activity was calculated as the percentage of inhibition in the reduction of nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) measured at 560 nm. Reduction of untreated cells were considered 100%.

Results

Determination of ROS in promastigotes

Amount of ROS produced by GL-AmB was ~2.4, ~2.1 and ~1.6 fold higher than AmB at 0.05, 0.1 and 0.2 μM doses, respectively (P < 0.001, Figure S4A). Interestingly, at IC50 dose for both GNP (2.5 μg/ml) and AmB (0.05 μM) amount of ROS produced was ~2 fold higher for GNP than AmB. Therefore, generation of oxidative stress by citrate-reduced GNPs is one of the possible reason for its antileishmanial efficacy. Amount of ROS produced by GNP, AmB and GL-AmB in promastigotes can be reduced to the basal level by pre-incubating the reaction with 1 mM NAC. Although a wide range of concentrations of AmB and GL-AmB were used in most experiments, results were shown only for those concentrations which had shown significant differences between AmB and GL-AmB-treated samples.

Determination of RNS in promastigotes

Amount of RNS produced in macrophages was also higher (~1.5 fold) for GL-AmB-treated cells than AmB-treated cells at all indicated doses (Figure S4B). Also, RNS produced by GNP and AmB is almost comparable. Therefore, production of higher oxidative stress is one of the possible mechanism of increased antileishmanial efficacy of GL-AmB compared to AmB.

SOD Assay

Activity of SOD was ~1.9 fold reduced in lysates which were prepared from 0.2 μM of GL-AmB-treated cells in comparison to AmB-treated cells after 6 h.

Supplementary materials

HPLC chromatogram of AmB (0.2 mg/ml) (A) and synthesized GL-AmB (amount equivalent to 0.2 mg/ml of AmB used in synthesis) (B). AmB standard curve based on HPLC determination (C).

Abbreviation: AmB, amphotericin B.

Zeta potential diagram of GNP, GL and GL-AmB (A). Tabular representation of measured average diameter and PDI of NPs by DLS (B).

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; GL, GNP-lipoic acid product; GNP, gold nanoparticle; PDI, polydispersity index.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) of crystalline GL-AmB characterized by the presence of four peaks corresponding to standard Bragg reflections. The diffraction peak of 38.2° relates to (111), 47.7° relates to (200), 65.3° relates to (220), and 77.1° relates to (311) facets of the face centre cubic (FCC) crystal.

Activity of NPs and AmB after 72 h treatment against LD promastigotes in vitro (A) and against intracellular amastigotes ex vivo (C). Comparative efficacy for AmB and GL-AmB against promastigote (C) and amastigotes (D).

Note: *P<0.05; ***0.01<P<0.001.

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; GL, GNP-lipoic acid product; GNP, gold nanoparticle.

Activity of NPs and AmB after 96 h treatment against LD promastigotes in vitro (A) and against intracellular amastigotes ex vivo (C). Comparative efficacy for AmB and GL-AmB against promastigote (C) and amastigotes (D).

Note: *P<0.05; **0.05<P<0.01; ***0.01<P<0.001.

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; GL, GNP-lipoic acid product; GNP, gold nanoparticle.

Cyto-toxicity assay on THP-1 cells after 72 h treatment with NPs and AmB (A). Hemolysis assay on human RBCs after 4 h treatment with NPs and AmB (C). DMSO (0.1%) used as negative control. Comparative efficacy of AmB and GL-AmB in cytotoxicity (B) and hemolysis (D) assay.

Note: *P<0.05; **0.05<P<0.01; ***0.01<P<0.001.

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; GL, GNP-lipoic acid product; GNP, gold nanoparticle.

In vitro activity of AmB and NPs after 48 h treatment against C. albicans (A). Comparative efficacy of AmB and GL-AmB against C. albicans (B).

Note: **0.05<P<0.01; ***0.01<P<0.001.

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; GL, GNP-lipoic acid product; GNP, gold nanoparticle.

Measurement of ROS produced by promastigotes after treatment with NPs and AmB for 6 h with or without 1 mM NAC (A). Measurement of RNS produced by amastigotes after measuring absorbance of Griess reagent at 540 nm under similar treatment conditions for NPs and AmB with or without 0.1 mM DPI (B).

Note: *P<0.05; **0.05<P<0.01; ***0.01<P<0.001.

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; GL, GNP-lipoic acid product; GNP, gold nanoparticle.

Protein carbonyl content was determined by DNPH-based spectrophotometric method from parasites treated with NPs and AmB after 6 h (A) and 12 h (B). Lipid peroxidation assay for promastigotes after treatment with NPs and AmB for 6 h with or without 1 mM NAC (C).

Note: *P<0.05; **0.05<P<0.01.

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; GL, GNP-lipoic acid product; GNP, gold nanoparticle; NS, not significant.

Semi-quantitative PCR for LD specific genes after treatment of parasites with AmB and NPs for 6 h (A) where -tubulin was used as loading control. SOD activity assay with LD cell lysates after treatment with AmB and NPs for 6 h (B) where activity of untreated cells were considered 100%. Semi-quantitative PCR for macrophage iNOS after treatment with macrophage-infected parasites with AmB and NPs for 6 h (C).

Note: **0.05<P<0.01.

Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; APX, ascorbate peroxidase; GL, GNP-lipoic acid product; GNP, gold nanoparticle; HSP, heat shock protein; iNOS, inducible nitric oxidase.; SCMT, S-adenosyl-L-methionine:C-24-∆-sterol methyltransferase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TryR, trypanathione reductase.

References

- 1.Rai M, Ingle AP, Birla S, Yadav A, Santos CA. Strategic role of selected noble metal nanoparticles in medicine. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2016;42(5):696–719. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2015.1018131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanan NA, Chiu HI, Ramachandran MR, et al. Cytotoxicity of plant-mediated synthesis of metallic nanoparticle: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(6):1725. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prakash P, Gnanaprakasam P, Emmanuel R, Arokiyaraj S, Saravanan M. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from leaf extract of Mimusops elengi, Linn. for enhanced antibacterial activity against multi drug resistant clinical isolates. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;108:255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harshiny M, Matheswaran M, Arthanareeswaran G, Kumaran S, Rajasree S. Enhancement of antibacterial properties of silver nanoparticles-ceftriaxone conjugate through Mukia maderaspatana leaf extract mediated synthesis. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2015;121:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.04.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shanmuganathan R, MubarakAli D, Prabakar D, et al. An enhancement of antimicrobial efficacy of biogenic and ceftriaxone-conjugated silver nanoparticles: green approach. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2018;25(11):10362–10370. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-9367-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salunke GR, Ghosh S, Santosh Kumar RJ, et al. Rapid efficient synthesis and characterization of silver, gold, and bimetallic nanoparticles from the medicinal plant Plumbago zeylanica and their application in biofilm control. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9:2635–2653. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S59834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Tian B, Li T, et al. Biosynthesis of Au, Ag and Au-Ag bimetallic nanoparticles using protein extracts of Deinococcus radiodurans and evaluation of their cytotoxicity. Int J Nanomedicine. 2018;13:1411–1424. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S149079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ovais M, Nadhman A, Khalil AT, et al. Biosynthesized colloidal silver and gold nanoparticles as emerging leishmanicidal agents: an insight. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2017;12(24):2807–2819. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2017-0233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hossein J, Katayoon K, Zahra I, Roshanak RM, Kamyar S, Thomas JW. A review of small molecules and drug delivery applications using gold and iron nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:1633–1657. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S184723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chowdhury R, Ilyas H, Ghosh A, et al. Multivalent gold nanoparticle-peptide conjugates for targeting intracellular bacterial infections. Nanoscale. 2017;9(37):14074–14093. doi: 10.1039/c7nr04062h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shutao G, Yuanyu H, Qiao J, et al. Enhanced gene delivery and siRNA silencing by gold nanoparticles coated with charge-reversal polyelectrolyte. ACS Nano. 2010;4(9):5505–5511. doi: 10.1021/nn101638u [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiaoning L, Sandra MR, Akash G, et al. Functional gold nanoparticles as potent antimicrobial agents against multi-drug-resistant bacteria. ACS Nano. 2014;8(10):10682–10686. doi: 10.1021/nn5042625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miao Z, Gao Z, Chen R, Yu X, Su Z, Wei G. Surface-bioengineered gold nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Curr Med Chem. 2018;25(16):1920–1944. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666180117111404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah M, Badwaik V, Kherde Y, et al. Gold nanoparticles: various methods of synthesis and antibacterial applications. Front Biosci. 2014;19:1320. doi: 10.2741/4284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voliani V, Giovanni S, Riccardo N, Fernanda R, Stefano L, Fabio B. Smart delivery and controlled drug release with gold nanoparticles: new frontiers in nanomedicine. Recent Pat Nanomed. 2012;2:34–44. doi: 10.2174/1877912311202010034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.AlMatar M, Makky EA, Var I, Koksal F. The role of nanoparticles in the inhibition of multidrug-resistant bacteria and biofilms. Curr Drug Deliv. 2018;15(4):470–484. doi: 10.2174/1567201815666171207163504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deray G. Amphotericin B nephrotoxicity. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;49:37–41. doi: 10.1093/jac/49.suppl_1.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oura M, Sternberg TH, Wright ET. A new antifungal antibiotic, amphotericin B. Antibiot Annu. 1955;3:566–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ha YE, Peck KR, Joo EJ, et al. Impact of first-line antifungal agents on the outcomes and costs of candidemia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:3950–3956. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06258-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mueller Y, Nguimfack A, Cavailler P, et al. Safety and effectiveness of amphotericin B deoxycholate for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in Uganda. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2008;102:9–11. doi: 10.1179/136485908X252142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sundar S, Sinha PK, Rai M, et al. Comparison of short-course multidrug treatment with standard therapy for visceral leishmaniasis in India: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:477–486. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62050-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Croft SL, Olliaro P. Leishmaniasis chemotherapy - challenges and opportunities. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1478–1483. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03630.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barratt G, Bretagne S. Optimizing efficacy of Amphotericin B through nanomodification. Int J Nanomed. 2007;2:301–313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mistro S, Gomes B, Rosa L, Miranda L, Camargo M, Badaró R. Cost-effectiveness of liposomal amphotericin B in hospitalised patients with mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22(12):1569–1578. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borba HHL, Steimbach LM, Riveros BS, et al. Cost-effectiveness of amphotericin B formulations in the treatment of systemic fungal infections. Mycoses. 2018;61(10):754–763. doi: 10.1111/myc.12801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou L, Zhang P, Chen Z, et al. Preparation, characterization, and evaluation of amphotericin B-loaded MPEG-PCL-g-PEI micelles for local treatment of oral Candida albicans. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017;12:4269–4283. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S124264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ribeiro TG, Chávez-Fumagalli MA, Valadares DG, et al. Novel targeting using nanoparticles: an approach to the development of an effective anti-leishmanial drug-delivery system. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9:877–890. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S55678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruni N, Stella B, Giraudo L, Della Pepa C, Gastaldi D, Dosio F. Nanostructured delivery systems with improved leishmanicidal activity: a critical review. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017;12:5289–5311. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S140363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loiseau PM, Imbertie L, Bories C, Betbeder D, De Miguel I. Design and antileishmanial activity of Amphotericin B-loaded stable ionic amphiphile biovector formulations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1597–1601. doi: 10.1128/aac.46.5.1597-1601.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jain K, Verma AK, Mishra PR, Jain NK. Characterization and evaluation of amphotericin B loaded MDP conjugated poly(propylene Imine) dendrimers. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med. 2015;11:705–713. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2014.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santos CMB, Da Silva SW, Guilherme LR, Morais PC. SERRS study of molecular arrangement of Amphotericin B adsorbed onto iron oxide nanoparticles precoated with a bilayer of lauric acid. J Phys Chem C. 2011;115:20442–20448. doi: 10.1021/jp206434j [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krzysztof T, Radosław S, Katarzyna S, et al. Amphotericin B-Silver hybrid nanoparticles: synthesis, properties and antifungal activity. Nanomedicine. 2016;12:1095–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.12.378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmad A, Wei Y, Syed F, et al. Amphotericin B-conjugated biogenic silver nanoparticles as an innovative strategy for fungal infections. Microb Pathog. 2016;99:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benincasa M, Pacor S, Wu W, Prato M, Bianco A, Gennaro R. Antifungal activity of amphotericin B conjugated to carbon nanotubes. ACS Nano. 2011;5:199–208. doi: 10.1021/nn1023522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gray KC, Palacios DS, Dailey I, et al. Amphotericin B primarily kills yeast by simply binding ergosterol. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:2234–2239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117280109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daniel SP, Ian D, David MS, Brandon CW, Martin DB. Synthesis-enabled functional group deletions reveal key underpinnings of amphotericin B ion channel and antifungal activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;17:6733–6738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta S, Dube A, Vyas SP. Antileishmanial efficacy of amphotericin B bearing emulsomes against experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Drug Target. 2007;15:437–444. doi: 10.1080/10611860701453836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pal A, Gupta S, Jaiswal A, Dube A, Vyas SP. Development and evaluation of tripalmitin emulsomes for the treatment of experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Liposome Res. 2012;22(1):62–71. doi: 10.3109/08982104.2011.592495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Italia JL, Kumar MN, Carter KC. Evaluating the potential of polyester nanoparticles for per oral delivery of amphotericin B in treating visceral leishmaniasis. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2012;8(4):695–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmad A, Wei Y, Syed F, et al. Isatis tinctoria mediated synthesis of amphotericin B-bound silver nanoparticles with enhanced photoinduced antileishmanial activity: a novel green approach. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2016;161:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dube E, Oluwole DO, Nwaji N, Nyokong T. Glycosylated zinc phthalocyanine-gold nanoparticle conjugates for photodynamic therapy: effect of nanoparticle shape. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2018;203:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2018.05.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Almeida L, Terumi Fujimura A, Del Cistia ML, et al. Nanotechnological strategies for treatment of leishmaniasis–a review. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2017;13(2):117–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.WHO fact sheet. Leishmaniasis; 2018. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs375/en/. Accessed 17 April, 2019.

- 44.Turkevich J, Stevenson PC, Hillier J. A study of the nucleation and growth processes in the synthesis of colloidal gold. Discuss Faraday Soc. 1951;11:55–75. doi: 10.1039/df9511100055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turcu I, Zarafu I, Popa M, et al. Lipoic acid gold nanoparticles functionalized with organic compounds as bioactive materials. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2017;7(2):43. doi: 10.3390/nano7120458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barwal I, Kumar R, Kateriya S, Dinda AK, Yadav SC. Targeted delivery system for cancer cells consist of multiple ligands conjugated genetically modified CCMV capsid on doxorubicin GNPs complex. Sci Rep. 2016;22:37096. doi: 10.1038/srep37096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masood A, Khan MO. Toxicity, stability and pharmacokinetics of amphotericin B in immunomodulator tuftsin-bearing liposomes in a murine model. J Antimicrob Chem. 2006;58(1):125–131. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Das S, Roy P, Mondal S, Bera T, Mukherjee A. One pot synthesis of gold nanoparticles and application in chemotherapy of wild and resistant type visceral leishmaniasis. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;107:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.01.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tan TR, Hoi KM, Zhang P, Ng SK. Characterization of a Polyethylene glycol-amphotericin B conjugate loaded with free AMB for improved antifungal efficacy. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):0152112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh K, Ali V, Singh KP, et al. Deciphering the interplay between cysteine synthase and thiol cascade proteins in modulating Amphotericin B resistance and survival of Leishmania donovani under oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2017;12:350–366. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shadab M, Jha B, Asad M, Deepthi M, Kamran M, Ali N. Apoptosis-like cell death in Leishmania donovani treated with KalsomeTM10, a new liposomal amphotericin B. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):0171306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paquet V, Carreira EM. Significant improvement of antifungal activity of polyene macrolides by bisalkylation of the mycosamine. Org Lett. 2006;8(9):1807–1809. doi: 10.1021/ol060353o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dinesh N, Neelagiri S, Kumar V, Singh S. Glycyrrhizic acid attenuates growth of Leishmania donovani by depleting ergosterol levels. Exp Parasitol. 2017;176:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2017.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carnpanero MA, Espuelas MS, Azanza JR, Irache JM. Rapid determination of intramacrophagic amphotericin B by direct injection HPLC. Chromatographia. 2000;52:827–830. doi: 10.1007/BF02491013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mohamed-Ahmed AH, Seifert K, Yardley V, Burrell-Saward H, Brocchini S, Croft SL. Antileishmanial activity, uptake, and biodistribution of an amphotericin B and poly(α-Glutamic Acid) complex. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(10):4608–4614. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02343-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Samuelsen JT, Kopperud HM, Holme JA, Dragland IS, Christensen T, Dahl JE. Role of thiol‐complex formation in 2‐hydroxyethyl‐methacrylate‐induced toxicity in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2011;96A(2):395–401. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shinitzky M, Inbar M. Difference in microviscosity induced by different cholesterol levels in the surface membrane lipid layer of normal lymphocytes and malignant lymphoma cells. J Mol Biol. 1974;85:603–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]