Abstract

Background

Due to the widespread use of mobile phones, dietary mobile apps are promising tools for preventing diet-related noncommunicable diseases early in life. However, most of the currently available nutrition apps lack scientific evaluation and user acceptance.

Objective

The objective of this study was the systematic design of a theory-driven and target group–adapted dietary mobile app concept to promote healthy eating habits with a focus on drinking habits as well as consumption of fruits and vegetables in adolescents and young adults, especially from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Methods

The design process was guided by the behavior change wheel (BCW). The development process comprised 3 stages. In stage 1, the target behavior was specified, and facilitators and barriers were identified. Furthermore, important insights into target group interests, needs, and values in the field of nutrition and apps were revealed. To this end, 2 empirical studies were conducted with the target group. In stage 2, results of stage 1 were translated into behavior change techniques (BCTs) and, finally, into app functionalities and features. Consequently, in stage 3, the concept was evaluated and optimized through expert interviews.

Results

Facilitators and barriers for achieving the target behavior were psychological capabilities (eg, self-efficacy), reflective motivation (eg, fitness), automatic motivation, social support, and physical opportunity (eg, time). Target group interests, needs, and values in the field of nutrition were translated into target group preferences for app usage, for example, low usage effort, visual feedback, or recipes. Education, training, incentives, persuasion, and enablement were identified as relevant intervention functions. Together with the target group preferences, these were translated via 14 BCTs, such as rewards, graded tasks, or self-monitoring into the app concept Challenge to go (C2go). The expert evaluation suggested changes of some app features for improving adherence, positive health effects, and technical feasibility. The C2go concept comprises 3 worlds: the (1) drinking, (2) vegetable, and (3) fruit worlds. In each world, the users are faced with challenges including feedback and a quiz. Tips were developed based on the health action process approach and to help users gain challenges and, thereby, achieve the target behavior. Challenges can be played alone or against someone in the community. Due to different activities, points can be collected, and levels can be achieved. Collected points open access to an Infothek (information section), where users can choose content that interests them. An avatar guides user through the app.

Conclusions

C2go is aimed at adolescents and young adults and aims to improve their fruit and vegetable consumption as well as drinking habits. It is a theory-driven and target group–adapted dietary mobile intervention concept that uses gamification and was systematically developed using the BCW.

Keywords: adolescents, young adults, mobile phone, mobile apps, mHealth, health behavior, healthy eating, motivation

Introduction

Background

Globally, diet-related noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) are the leading cause of death and disease burden [1,2]. Numerous studies emphasize the association between a suboptimal diet and deaths due to NCDs such as stroke, heart disease, or type 2 diabetes [3-6]. Among dietary risk factors for NCDs are the low consumption of fruits and vegetables [7-9] and the high consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages [10-14].

German survey data highlights the high prevalence of overweight and obesity. Almost 60% of the population is overweight or obese (women 51% and men 66%) [15]. Among the younger population, about 16% of girls and 18.5% of boys in the age between 14 and 17 years are overweight or obese [16], likely due to a more sedentary lifestyle characterized by decreased physical activity and unbalanced dietary behavior [15]. Only 7% of the girls and boys in Germany in the age between 14 and 17 years follow the dietary recommendations for the consumption of 2 portions of fruits and 3 portions of vegetables each day. On average, 0.9 portion each of vegetables and fruits per day are consumed [17]. Nearly, 23% of boys and 17% of girls drink sugar-sweetened beverages daily [18], whereas recommended beverages are water and unsweetened teas [19]. Data from the United States also reveal similar results. American guidelines recommend 2.5 cups of vegetables and 2 cups of fruits per day (for a calorie level of 2000 kcal) as well as drinking water and reducing consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages [20]. However, less than 50% of children and adolescents meet dietary recommendations for any food group [21]. The level of education positively influences food consumption and, thus, the quality of the diet [22,23]. Higher school education and higher income result in a lower body mass index [15,16].

To summarize, nutrition surveys highlight that adolescents and young adults have unbalanced diets [17,24,25], especially adolescents and young adults in disadvantaged circumstances [17]. As adolescence is characterized by cutting ties with the parents’ household and the development of one’s own lifestyle, this could be a reasonable stage of life for behavior change interventions [26], in particular for focusing on adolescents and young adults with lower education levels.

Digitalization and Mobile Health

State-of-the-art mobile phones provide new possibilities for dietary interventions. Mobile health (mHealth) is an emerging field and describes various health services offered on portable devices. These include health apps in various areas, such as nutrition, fitness, wellness, diagnostics, and therapy [27], but systematic studies in the area of mHealth are scarce [28-30]. Studies also highlight missing user acceptance of nutrition apps, for which the relatively high usage effort might be a reason [31,32]. Rohde et al concluded that app usage in the long term is influenced by user- and app-related acceptance factors [32]. The former highlights the importance of knowing the target group for designing accepted mHealth interventions; the latter emphasizes the importance of considering different app characteristics, for example, implementing instructions or motivators for engagement and adherence in app-based interventions [32].

In the context of long-term adherence and acceptance of mHealth interventions, gamification is an emerging field. Gamification means that playful elements such as points or leaderboards are used in a context that is normally not played (for example using a quiz, where one can earn points, instead of just giving information) [33,34]. Gamification can be a motivational component of digital behavior change interventions by playfully making uninteresting topics interesting and, thereby, engage users in the long term [34].

Theory Guidance for Intervention Development

The behavior change wheel (BCW) is a framework for developing health interventions [35]. It proposes a systematic design process of behavior change interventions that helps to translate theory into practice [30].

The health action process approach (HAPA) is a health behavior model and, as a stage model, an interesting template for the theory-based development of dietary health messages that can be adapted to persons at different stages of the behavior change process [36]. It was successfully applied in several nutrition behavior change interventions [37-39].

Objective

The aim of this study was to describe the iterative concept development and the final concept of a theory-based and target group–adapted mobile app for motivating adolescents and young adults (aged 14-25 years), especially from disadvantaged backgrounds, to improve their dietary habits with respect to the consumption of fruits and vegetables, as well as drinking behavior.

Methods

Overview

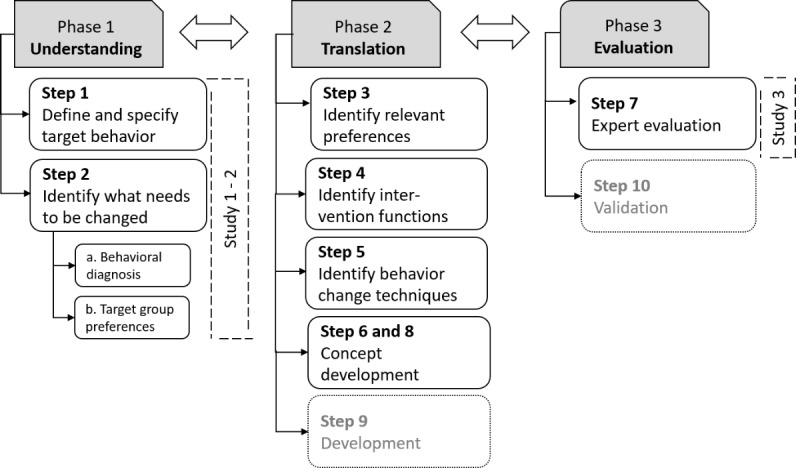

The app design process was guided by the BCW [40]. After defining the problem and the 3 target behaviors, the app design process followed 3 stages (Figure 1): Phase 1, specifying the target behavior and identifying what needs to change to achieve it; Phase 2, translating results into app functionalities and features; and Phase 3, expert evaluation of the concept. In total, 3 empirical studies were conducted to derive relevant app features and content as well as to optimize the concept.

Figure 1.

Systematic design process of the dietary mobile app for adolescents and young adults. Steps 1-7 (in black font) are discussed in the text; steps 9 and 10 (in grey font) are being or will be carried out.

Phase I: Understanding Behavior and Target Group Preferences

Step 1: Define and Specify Target Behavior

In total, 3 target behaviors were chosen by the author (AR) by identifying possible target behaviors through literature search and opinions of nutrition experts from the Friedrich Schiller University Jena. A list of potential target behaviors was shortened using the following criteria: Likely impact of the target behavior on outcome, ease of reaching target behavior, possible positive or negative spillover effects, and ease of measurement [40]. Each criterion was rated as unacceptable, unpromising but worth considering, promising, or very promising. Rating and selecting the target behavior were supported by empirical research (Step 2b). Upon selection of the most promising target behaviors, they were specified in detail and context: who, when, where, how often, and with whom will the target group perform the target behavior?

Step 2: Identify What Needs to Change to Reach Target Behavior

Behavioral Diagnosis

The capability-opportunity-motivation-behavior (COM-B) model was used to identify what needs to change for adolescents and young adults to achieve the target behavior. Evidence from the literature and empirical research informed this procedure by exploring target group’s capabilities, motivation, and opportunity to achieve the target behaviors (eg, which physical capabilities are needed to eat 2 portions of fruit per day?) and the need for change. Next, each capability, motivation, and opportunity was evaluated as feasible or not for implementing in a dietary mobile app.

Target Groups Preferences (Sampling From Empirical Studies 1 and 2)

Besides informing behavioral diagnosis, study results were also analyzed to explore the target group’s preferences for app characteristics, behavior change techniques (BCTs), features, and content. The ethics committee of the University noted no ethical concerns (processing number 4850-06/16).

Study 1: Nutrition and Apps From the Target Group’s Perspective

The objective of this study, conducted in 2016, was to get insights into nutrition habits, values, and needs, and to develop ideas as to how nutritional behavior and health among adolescents and young adults could be improved through mobile apps. Study participants (n=11) tested the German dietary mobile app Was ich esse [41] for 1 week before face-to-face, semistructured interviews. The participants were between 14 and 21 years old (average age: 18 years, SD 2.4) and mostly women (n=8). A total of 5 participants went to secondary school at the time of the study. Others were university students (n=3), trainees (n=1), volunteers (n=1), or were looking for an apprenticeship (n=1). The audio-recorded material was transcribed and analyzed by means of content analysis [42]. Data segments were coded into the following topics: (1) mobile phone and app usage, (2) test app experiences, (3) nutritional habits, (4) nutrition values, (5) nutritional improvement wishes and strategies, and (6) understanding of health. Additional information on recruitment, compensation, the interview guide, and the test app are provided in Multimedia Appendix 1.

Study 2: Nutrition and Mobile Phone Apps—Interests, Needs, and Values Among Adolescents and Young Adults

This study aimed for a better understanding of available mobile phone resources, app use, and needs as well as interests and values in the field of nutrition of adolescents and young adults. To this end, a questionnaire was developed and administered as a paper-pencil version. It included the following topics: mobile operating system, mobile phone rate, favorite apps, experiences with dietary mobile apps, importance of different app characteristics (eg, importance of customizability), and nutritional interests (eg, sports nutrition, health, and food waste) and values (eg, freshness of food and self-cooked meals). Data were analyzed descriptively. The inclusion criterion for participation was an age between 14 and 25 years. Teachers and social workers in Jena were contacted via mail to secure them as gatekeepers. In total, 210 participants from 5 different organizations took part (females n=99, males n=108, no information provided n=3). The average age was 18 years (n=208, SD 2.4; no information provided n=2). The youngest and oldest person was 15 and 25 years old, respectively. Participants went to vocational school (Berufs(fach)schule) (n=164). Others stated that they had participated in vocational preparation classes (n=27) or went to high school (Gymnasium) (n=11). One person each went to secondary school (Hauptschule) and regular school (Regelschule); 4 persons stated other (no information provided n=2). Additional information on recruitment, compensation, and the scales in the questionnaire are presented in Multimedia Appendix 1.

Phase II: Translation of Research Results Into App Content and Features

Step 3: Identify Relevant Target Group Preferences

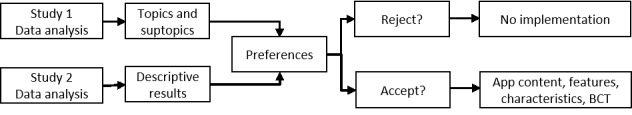

Results from studies 1 and 2 were compared and merged in target group preferences, and an acceptance-rejection process followed (Figure 2). Decisions of the author (AR) for rejection or acceptance of target group preferences were based on APEASE criteria [40]: Is the respective preference a ffordable, p racticable, e ffective, and a cceptable, are s ide-effects expected or offense against e quity? If all criteria are met or at least rated probably, the preference was accepted and further implemented as app content, app features, BCTs, or considered as important app characteristics (Steps 5 and 6).

Figure 2.

Process of identification of relevant target group preferences. BCT: behavior change technique.

Step 4: Identify Intervention Functions

This step aimed to move from understanding the behavior to selecting intervention functions. This was supported by a matrix of links between COM-B and intervention functions [40]. Appropriate intervention functions were selected by using the APEASE criteria.

Step 5: Identify Behavior Change Techniques

To choose which BCTs can deliver the intervention functions, a linking was used [40]. The list of candidate BCTs (n=118) was narrowed by APEASE criteria. The rating was supported by the evidence of effectiveness for promoting healthy food choices, and on the basis of target group preferences.

Step 6: Concept Development (Prototype I)

Together with target group preferences, the BCTs were translated into app features, content, and characteristics. Content development of feedback was guided by HAPA for preintender and intenders and gamification aspects were implemented to enhance user engagement with the app [30,34].

Phase III: Evaluation

Step 7: Expert Evaluation

The concept was evaluated and optimized using 3 evaluation criteria: (1) acceptance among target group, (2) positive health effects due to app use, and (3) technical feasibility. To this end, professionals with knowledge of the target group, app development or nutrition behavior were recruited. Recruitment took place via emails and later personally by telephone. Ultimately, 8 face-to-face interviews were conducted with experts of the following professions: Marketing, 2 social workers/teachers, dietician, app development, media psychology, psychotherapist, and a person of the target group itself. The interviews started with the presentation of the concept using mock ups. The semistructured interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data were evaluated with structured qualitative content analyses [42].1 The following 5 topics were discussed: (1) important features and needs of a dietary mobile app among the target group, (2) advantages of the concept, (3) disadvantages of the concept, (4) suggestions to improve the concept, and (5) technical feasibility.

In the next step, the recommendations for improving the concept were rated using APEASE criteria and were either accepted and implemented, or rejected and not implemented.

Step 8: Final Intervention (Prototype II)

On the basis of the evaluation, the concept was adapted by defining the final features and functionalities of the app.

Results

Phase I: Understanding Behavior and Target Group Preferences

Step 1: Defined and Specified Target Behavior

A range of target behaviors was listed, such as consumption of more vegetables, fruits, water, tea, fibers, or eating less saturated fatty acids. Following this, an important point in rating the ease of achieving the behavior was to avoid the feeling of waiver in nutritional terms, so that a target behavior does not forbid, but permits and increases, consumption of food [43].

Finally, 3 target behaviors, in line with German intake recommendations [19] were chosen: The consumption of (1) 2 portions of fruits per day, (2) 3 portions of vegetables per day, and (3) drinking 1.5 L or more of unsweetened beverages per day to decrease the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (only nonalcoholic beverages are considered). To achieve the target behaviors, adolescents and young adults have to eat and drink fruits, vegetables, and sugar-free drinks at mealtimes (or in between), and often enough to achieve the respective target behavior. They can do it anywhere and either by themselves or with others.

Step 2: Identified What Needs to Change to Reach Target Behavior

Behavioral Diagnosis

The results of the behavioral diagnosis revealed facilitators and barriers to the target behavior in the following COM-B components: psychological capabilities (eg, nutrition education, self-efficacy, and risk perception), reflective motivation (eg, weight loss, satiety, fitness, and illness prevention), automatic motivation, social support, and physical opportunity (eg, time and financial resources). An overview of the results with quotes from study participants and references is displayed in Multimedia Appendix 2.

Target Group Preferences: Empirical Study Results

Study 1

An excerpt of the results in 4 of the 6 main topics is presented in Table 1. In addition, Multimedia Appendix 3 presents a complete overview of the results.

Table 1.

Excerpt of results from study 1.

| Main topic, subtopics | Quotes (translated) | |

| Mobile phone and app usage |

|

|

|

|

Mobile phone is used for entertainment and when bored (eg, games and videos) | Jana: “I use my mobile phone when I'm bored or when I have to wait for the bus or something, then I play games.” |

| Nutritional values |

|

|

|

|

Cooking stands for independency | Caro: “Yeah, for later, if maybe I have a family and I cannot cook, that would be a bit ... And cooking is also important to me, so I do not always depend on someone.” |

|

|

Spending on food should be kept low | Leon: “We like to eat exotic fruits. But you always have to see how much money you have at your disposal.” |

| Nutritional improvement wishes and strategies |

|

|

|

|

Eating healthier | Jana: “I often wish that I ate healthier.” |

| Test app experiences |

|

|

|

|

High usage effort through tracking | Daria: “So, I did not continue using the app because it was very time-consuming tracking everything and properly. At the beginning it was a lot of fun, but eventually it got harder, because sometimes you do not think about tracking.” |

|

|

Visual feedback is used as consumption orientation and promotes self-control | Tino: “Through the app I've noticed that I do not eat enough vegetables. That's why I bought some cucumbers or tomatoes.” |

Study 2

The operating system most used was Android (Google) and most of the participants used a mobile flat rate. Among the participants’ favorite apps were communication and social media apps (WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram), video apps such as YouTube, and gaming apps such as Clash of Clans and Clash Royal. In all, 26% of the participants had experiences with apps in the area of nutrition, above all recipe apps. The most interesting subjects in the area of nutrition were health, cooking, and sports nutrition. Good taste, satiety, and freshness of food were the most important nutritional values. The most important app characteristics were free of charge, contact to friends/family, and fast use. Multimedia Appendix 3 gives a full insight into the results.

Phase II: Translation of Research Results Into App Contents and Features

Step 3: Identified Relevant Target Group Preferences

An excerpt of results of the process of the identification and selection of relevant target group preferences for app characteristics and features is presented in Table 2. For the derivation of the preferences, all subtopics of the topics (1) to (5) of study 1 were included as well as the most frequent answers of study 2. Results that were rated mostly not important and partly true with tendency to not important were not considered to derive preferences. For example, Nutrition habits of other cultures and Nutrition and skin were both mostly rated as partly interesting (n=91; n=95). The first was not considered to derive a preference because it shows a tendency toward not interesting (n=72). However, the latter showed a tendency toward interesting (n=65) and was therefore considered to derive a preference.

Table 2.

Excerpt of identified and selected target group preferences for app characteristics and features.

| Study 1 | Study 2 | Target group preferences for app characteristics and features, based on findings from studies 1 and 2 | Accept or reject | |

| Topic | Subtopic | Results |

|

|

| Mobile phone and app usage | Mobile phone is used for entertainment and when bored (eg, games) | Important app characteristics: Entertainment | Features for use when bored/individual time of usage | Accepta |

| Mobile phone and app usage | Listening to music | —b | Music | Rejectc,d |

| Test app experiences | Disadvantage: High usage effort through tracking (as a result not everything was tracked) | Important app characteristics: Fast use | Supporting low user effort and fast use | Accepta |

| Test app experiences | Advantage: Test-app use for comparison of visual feedback with others | Favorite apps are mostly communications apps | Social comparison | Accepta |

| Test app experiences | Improvement suggestion: More feedback through additional evaluation charts | — | Different evaluation charts | Rejectc,e |

aMaintain suspense and adherence.

bNot applicable.

cNot relevant for target behavior/not in line with target behavior.

dNot affordable as incentive.

eFocus shall be kept on portions not on calorie intake.

Step 4: Identified Intervention Functions

Candidate intervention functions were education, persuasion, incentivization, coercion, training, restriction, environmental restructuring, modeling, and enablement. The rating of theses for both fruits and vegetables, and drinking behavior led to the selection of education, persuasion, incentivization, training, and enablement.

Step 5: Identified Behavior Change Techniques

According to the APEASE criteria, 14 BCTs were derived to bring about behavior change (Table 3).

Table 3.

Intervention functions with capability-opportunity-motivation-behavior components and behavior change techniques (including evidence of effectiveness and target group preferences).

| Intervention functions | BCTsa with evidence from literature | Target group preferences |

| Education | Self-monitoring of behavior [44-46] | Tracking for promoting awareness of eating behavior |

| Education | Feedback on behavior [47-50] | Tips are motivational (low cost and easy tips) |

| Education | Information about health consequences [47,51,52] | —b |

| Education | Prompts/cues [53] | Support through reminder |

| Persuasion | Information about health consequences [47,51,52] | — |

| Persuasion | Feedback on behavior [47-50] | Tips are motivational (low cost and easy tips) |

| Persuasion | Verbal persuasion about capability [34] | — |

| Persuasion | Social comparison [49,54,55] | Social comparison |

| Incentivization | Feedback on behavior [47-50] | Tips are motivational (low cost and easy tips) |

| Incentivization | Self-monitoring of behavior [44-46] | Tracking for promoting awareness of eating behavior |

| Incentivization | Nonspecific incentive/reward (includes positive reinforcement) [49,56,57] | Gamification |

| Training | Instruction on how to perform a behavior | Tips are motivational (low cost and easy tips) |

| Training | Feedback on behavior [47-50] | Tips are motivational (low cost and easy tips) |

| Training | Self-monitoring of behavior [44-46] | Tracking for promoting awareness of eating behavior |

| Training | Graded tasks [58] | — |

| Enablement | Action planningc [44] | — |

| Enablement | Coping planningc [44] | — |

| Enablement | Goal setting (behavior) [59] | Goal setting |

| Enablement | Discrepancy between current behavior and goal [46] | Tracking for promoting awareness of eating behavior |

| Enablement | Self-monitoring of behavior [44-46] | Tracking for promoting awareness of eating behavior |

| Enablement | Graded tasks [58] | — |

| Enablement | Social support (unspecified) [55] | — |

aBCT: behavior change technique.

bNot applicable.

cBased on the health action process approach [36].

Step 6: Developed Preliminary Concept (Prototype I)

This step resulted in the development of the Challenge to go (C2go) app concept. Multimedia Appendix 4 shows how target group preferences and BCTs were matched and jointly translated into app features.

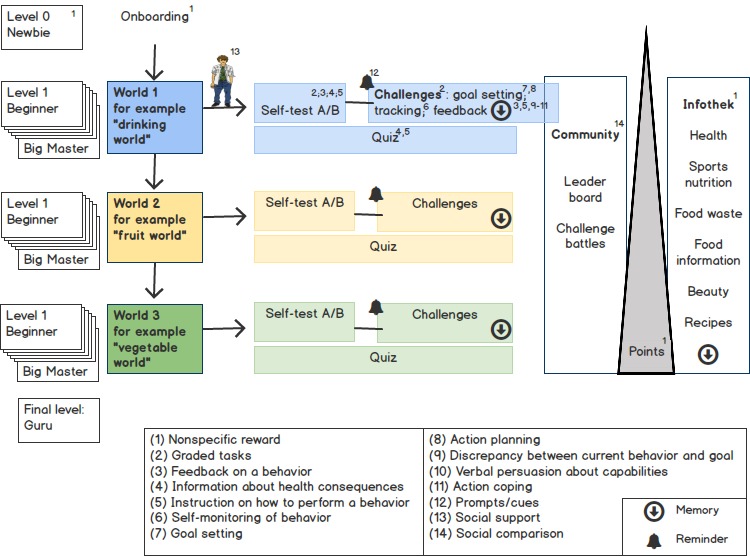

The following section gives an overview over the concept (Figure 3). After onboarding, the user can choose among 3 worlds: the drinking, the vegetable , or the fruit world. In each world, users can accept challenges and participate in a quiz. To get access to the challenges, users must go through self-tests. Consequently, in a challenge, the user must choose a behavioral goal from a list that he or she tries to achieve, for example, in the fruit world, one portion of fruit per day for 1 week. Challenges can be played alone or against someone else in the community. Different feedback is given to motivate and to empower the user to achieve his or her challenge goals, for example, the informative feedback after a lost challenge gives tips on how challenge goals can be reached. Each tip is stored and always accessible for the user. For further support, reminders can be set. Through different activities users earn points and achieve levels. The points open access to the Infothek, where users can choose content that is of their interest. The content received from the Infothek is stored and always accessible. A leaderboard compares user scores in the community, which is made up by other app users. Through passing challenges, users ascend in levels all the way up to Big Master. After completing a world, the next world can be selected. If the user has reached the highest level in every world, he or she becomes a Guru. Through the whole app, users are guided by an avatar.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of C2go.

Phase III: Evaluation

Step 7: Expert Evaluation

Data from expert evaluation and rating results suggested changes for the following app features: worlds, challenges, feedback, Infothek, and quiz. Furthermore, the issue of usage motivation was discussed (Table 4).

Table 4.

Concept changes after expert evaluation.

| App feature/characteristic | Prototype I | Prototype II |

| Challenges | Strict defined rules to reach goals | Easing the rules: More jokers for the users of the drinking world in the Big Master level |

| Feedback | Visual feedback | More visual feedback, for example, a smiling avatar for rewarding consumption of water |

| Feedback | Informative feedback (tips) | Optional extra button for more information, the user can choose if he/she wants more information concerning feedback |

| Feedback | —a | Reflective questions in feedback, for example, What are your best tips for a friend to encourage him to drink more water? |

| Feedback | — | Goal-orientated feedback: Asking an introductory question, linking the tips to the answer and thereby to the user’s goal |

| Usage motivation of app | Feedback development: Focus on preintender and intender | Informative feedback focuses on intenders only, preintenders are not considered. This decision was supported by literature, as health apps are more likely used by health-conscious people [31] |

| Worlds | — | Bonus worlds: Might be possible with an update of the app (menu button bonus worlds) |

| Worlds | Worlds are started one after the other | The worlds can be played simultaneously |

| Infothek | Point-related access or as a present | More frequently access: Through reduction of the distance of the points |

| Infothek | Information about healthy snacks/drinks | Including more information about healthy snacks and drinks |

| Infothek | Health, food waste, and beauty are topics | Content ideas for the following topics: (1) Health : Where does enjoyment of taste start and where does it end (start of addiction); mechanism of resorption of nutrients; food waste: Shelf life of food, seasonality of fruits and vegetables, environmental pollution; (2) Beauty: Cosmetics without any animal testing |

| Quiz | Answering question with yes/no; assigning answers | Answering questions with drag and drop mechanisms |

aNot applicable.

Step 8: Final Intervention (Prototype II)

The following sections describe the app features of Prototype II in detail. Further information regarding interventions functions, BCTs, and COM-B components are given in Multimedia Appendix 4.

Onboarding

Onboarding, that is, the way a user is introduced into the app content, is important to motivate the user for adherence [33]. As such, the app starts with an introductory question (Textbox 1).

Introductory question.

Where can Challenge 2 go support YOU the most?

Live healthier

Feeling good in my body

More fitness and performance

The introductory question is used to make users curious and motivate them to use the app through connecting his or her personal aim with app usage and selecting a question that can only be answered correctly, so that the user cannot lose and does not become demotivated [33]. Depending on the answer, a progress bar representing the guru status is implemented, and either titled Health Guru, Wellbeing Guru, or Performance Guru. A user reaches the Guru level after succeeding in all 3 worlds.

Consequently, a tutorial gives a brief overview of the app and how to use the app [32,33]. Afterwards, profile settings allow enhancement and customization of the app [33] and are associated with the selection of the avatar in terms of age and sex.

Self-Test

Each world starts with a self-test, which comprises 2 parts. The first part is a 24-hour dietary recall (eg, vegetables in the vegetable world). Results of this recall are used to divide users into HAPA stages—either intender, if dietary guidelines are not met, or actor, if guidelines are met [19]. The second part is a quiz, which serves as an introduction into the world concept and challenge rules and basics of nutrition education. The answer of each question is formulated depending on the HAPA stage of the user [36] and personal app aim (Textbox 2 for an example), which are stated by the user. After completing both parts of the self-tests, the user gets access to the challenges.

Example of a quiz question from the second part of the self-test. Example for a user whose personal aim is to live healthier.

How much should we drink at least a day?

0.5 L

1.5 L

1 L

3 L

Dissolution: Drinking (at least) 1.5 L per day of sugar-free drinks is good for you and helps you to get closer to your goal: to live healthier.

Challenges

The challenges are implemented for the user to reach self-imposed consumption goals, which can be chosen out of a list, for example, 3 servings of vegetables per day in the vegetable world or 3 portions of unsweetened beverages in the drinking world (level Adept in Table 5).

Table 5.

Levels in the drinking world of the app.

| Phase | Level |

| After selecting first world | Beginner |

| After completing self-test B | Climber |

| After the first challenge (24-hour-Challenge) | Adept |

| 3 portion challenge | Adept pro |

| 4 portion challenge | Expert |

| 5 portion challenge | Expert pro |

| 6 portion challenge | Master |

| 6 portion challenge + no sugary drinks | Big Master |

In the drinking world, a sugar mountain builds up additionally, while tracking sugar-sweetened beverages, which users must reduce through answering quiz questions before attacking the next challenge. In addition, in the fruit and vegetable world, it is not only quantity, but also quality, that counts. Users are motivated to eat as many colors as possible, as recommended in other studies [39,60]. In every world, the aim is to get better in behavioral terms from challenge to challenge up to the highest level, called Big Master, which meets the target behavior. To pass the challenges, users get support through feedback and tips. Before finishing a world successfully, every user must play the Big Master challenge, even if he or she is already carrying out the behavior and finishing the quiz.

Feedback and Community

Different feedback is implemented in the C2go app: visual, informative, motivational, evaluative, and competitive. An avatar, which is intended as social support [36], gives some visual and all informative, motivational, and evaluative feedback. The avatar rewards user’s desirable behavior with a facial expression (smiling face). Other visual feedback is given through progress bars for different features (self-test, challenges, quiz, and overall progress in app that represents the Guru Status) and a graph for an actual versus target feedback for the target behavior. Informative feedback contains messages relevant for intenders (based on HAPA [44]) by encouraging action coping (overcoming barriers, including reflexive questions) and action planning (when, how, where implementing behavior, including instructions on how to perform a behavior) to close the gap between intention and actual behavior [36,39]. Motivational feedback is given through encouraging messages that should sustain intention and self-efficacy [34,48]. Similarly, self-efficacy will be boosted by evaluative feedback [34,39]. When creating feedback, care was taken that this was formulated in a positive way [32,48] and using colloquial language [39]. For examples, refer to Table 6. Furthermore, competitive feedback is given through a leaderboard in the community [34]. In addition, challenges can be played alone or against other app user in the community to promote motivation for behavior change through social comparison and competition [54,61]. The community consists of all app users.

Table 6.

Feedback examples.

| Feedback type | Time point | Example |

| Motivational | During challenges | Great first 7 days! |

| Evaluative | After a challenge | Try again: the next level is already waiting for you! |

| Informative | After a challenge | Drink a portion of unsweetened beverage with each meal, for example, (mineral) water or herbal/fruit tea (warm or cold) |

Reminder

Reminders are push notifications and can be set to support users on the way to meeting their goals. Furthermore, they function as a re-engagement tool [53]. Types of different reminders are presented in Table 7. Every reminder can be switched off or on.

Table 7.

App reminders and time points.

| Reminder | Time point |

| Consumption of target behavior | From 9 am to 9 pm, every 3 hours |

| Tracking | 9 pm |

| Start of challenge | 9 am |

| End of challenge day | 9 pm, if necessary next day 7 am und 12 pm |

| End of a challenge | Immediately, if necessary 36 hours and 48 hours later |

| Infothek | If access has been granted |

Quiz

In terms of content, the quiz aims to provide knowledge about the health-related value of each target behavior and the national intake recommendations. To this end, each world has its own quiz, for example, the fruit world quiz contains questions regarding fruit intake recommendations and associated health benefits and risks (Textbox 3 for an example). All questions must be answered correctly to complete the respective world. Wrongly answered questions will be repeated later.

Example of quiz question.

How long can humans survive without liquid intake?

2-4 days

1 week

1 day

50 days

Dissolution: We (humans) can live without solid food for more than a month, but without drinking we die after 2-4 days!

Infothek

The Infothek is an information section where users get access to interesting information regarding 6 nutrition-related topics, which were derived from study results described above: health, food information, beauty, sports and food, food waste, and recipes. Users get access at certain scores to get motivated to app usage and reward it. Regardless of the score, once a week access to the Infothek is given to re-engage the user. Information is predominantly in written form (short messages). Also, short videos and podcasts are intended.

Gamification Approach

The C2go app implements severely playful elements, such as points, levels, leaderboard, challenges, onboarding, feedback, progress bars and customization, to engage users.

Discussion

Overview

Mobile phone-based interventions are increasingly used to promote a healthy lifestyle [30,62-65]. In this study, a mobile phone app was considered as a very acceptable tool for the delivery of a nutrition intervention for adolescents and young adults, as mobile phone usage is widespread across all education and income levels [66]. Furthermore, adolescents and young adults are at a stage of life where their own lifestyles, including eating styles, are developed and established. The empirical study results described above confirm the general openness for, and interest of adolescents and young adults in, a dietary mobile app. Next, other digital health interventions were rated as helpful and satisfactory by adolescents and young adults [57,67,68] and other age groups [69,70]. Studies by others have demonstrated that mobile phone apps are widely accepted by users for intervention delivery in the field of healthy eating [30,62,71]. Despite the growing interest in mHealth research, the development of a theory-driven app is not well described in the scientific literature [30]. Furthermore, to our knowledge, no dietary mobile app has been designed to meet the needs and interests of adolescents and young adults in Germany. Our study provides a step-by-step description of how evidence (eg, from empirical studies with the target group) and theory can be translated systematically into an app concept in the field of mHealth for contributing to the prevention of NCDs.

Systematic Design Process

The concept for the C2go app was designed along the BCW and based on the input of the target group as well as the literature analysis. The BCW has been used by other researchers to guide the development of mHealth interventions [30,72].

Effective interventions need theory guidance [36,73]: Using a framework helps design interventions systematically, deriving factors that need to be changed and avoiding intervention development based on personal experiences, favorite theories, or superficial analyses [40,73,74]. Besides this, theory-based interventions help to understand which, and how, techniques are effective, and results can be used to optimize theoretical concepts. Furthermore, using theory in research is also helpful for the communication between researches and disciplines [73]. Often, the use of underlying theories and concepts in intervention trials is not well described. Theories are only mentioned as frameworks but descriptions of how they were integrated into the scientific design process are often lacking [74]. In this study, the use of the BCW as a framework permitted the systematic and comprehensive design process, which was underpinned by a model of behavior change and a behavioral diagnosis of the target behavior, before starting the design process. However, it is necessary to expand the BCW regarding the derivation of empirical study results and its translation into BCTs and, finally, into mHealth app features [30]. This could minimize the influence of individual expertise, creativity, and reasonable decision of scientists on which features should actually be implemented in the app [30].

A major strength of this study was the examination of the behavior, interests, needs, and values of the target group, because digital interventions are most engaging when they are matched to the target group’s characteristics, needs, expectations, and skills [75]. Following this, other studies revealed that involving the target group throughout all phases of intervention development is important to make it more relevant to their life [30,63,68]. Our study therefore aimed at focusing on adults from disadvantaged backgrounds. Therefore, attempts were made to recruit study participants in (public) places with lower educational background in particular, for example, vocational school.

In total, 3 target behaviors were initially chosen, because concentrating on many or unspecified target behaviors (eg, whole nutritional intake) is assumed to be less effective than considering only a few and specified target behaviors (but then intensely) [76]. The selection of the target behaviors was indirectly confirmed by the target group, as beverages, fruit, and vegetables were voted as easy-to-track food. A further advantage of choosing the 3 target behaviors is that they focus on promotin g individual behaviors, for example, more fruits, instead of forbidding food (eg, eat only 1 piece of candy per day).

Altogether, study results along with literature searches were used to support the behavioral diagnosis, the identification of intervention functions, and BCTs. The behavioral diagnosis revealed that certain capabilities (eg, psychological capability: awareness of consumption), opportunities, and motivational aspects are needed to establish healthy eating habits. Furthermore, study results together with evidence from the scientific literature were used to identify 5 intervention functions and 14 BCTs. The latter were translated into features of the C2go app.

Final Intervention: The Challenge to Go App

The C2go app concept targets improved drinking habits as well as increased fruit and vegetable consumption among adolescents and young adults. To this end, users choose from 3 worlds: the drinking, the vegetable, or the fruit world. A core feature of the C2go app concept is the use of challenges. These consist of goal-setting and self-monitoring for target behavior. Both techniques were requested by participants and are supported by evidence from the literature [36,45,58,77,78]. Focusing on BCTs for effective behavior change interventions is important. Nevertheless, considering determinants of engagement is also crucial [75]. Therefore, the C2go app concept implements various game elements and process motivators, which reward the process of behavior change. Examples are points, levels for status gain, rankings, or engagement loops through challenges aiming at edutainment and loyalty [33,34]. Gamification approaches can provide motivation in settings where information only is not sufficient to bring about change [34]. Various other mHealth interventions used gamification for promoting user engagement successfully [30,43,63]. Concentrating on process motivators instead of long-term, logical outcome motivators (eg, prevention of NCDs) is proposed to influence self-efficacy for behavior change positively and more effectively [79].

The individual choice of worlds and, inter alia, the setting of individual goals support customization [33] to satisfy different needs and motivation for app use (engagement). Reminders were also implemented to increase user engagement [53]. Furthermore, the implementation of an avatar will improve user engagement and acceptance [80].

Different feedback was implemented to motivate app usage [54] and behavior change. Implemented informative feedback targets intenders. This serves to boost self-efficacy, thereby helping to overcome barriers and to achieve target behavior [36,51]. Visual feedback through progress bars was used to replace possible missing intrinsic motivation for behavior change [34]. Evaluative feedback, such as Congratulations if challenges are passed or encouraging feedback if challenges are not passed, were implemented to increase self-efficacy [43]. Motivating messages serve to increase self-efficacy in encouraging the idea that skills for succeeding are available [34]. Evaluative, informative, and motivating feedback is given through an avatar that was implemented for identification and positive learning effects [34]. When formulating this feedback, it was important to select positive language to increase the self-efficacy and satisfaction of the user [48]. Competitive feedback comes from the community and the leaderboard [34,43].

Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations must be considered when interpreting the findings of the present approach. First, the design, development, and implementation of mHealth concepts take time. Consequently, by the time of implementation, technology and target group interests may have evolved [30]. Second, regarding the target behaviors, the app focused on drinking and fruit and vegetable consumption only. Other food groups and nutrition behaviors (eg, snacking) could be targeted in the app at a later stage of development, along with physical activity. This provides opportunities for future research and extension of the app. Third, the participants who assisted in the app development were only from 1 region in Germany, and they may have had a bigger interest in nutrition or apps as nonparticipants. Future investigation should include a more diverse group of participants.

The next step is the validation of the C2go app concept to demonstrate its impact on drinking and fruit and vegetable consumption, as well as its usability in a controlled intervention trial. Moreover, financial opportunities for sustainable maintenance possibilities of scientific applications must be investigated.

Conclusions

C2go is a theory-based and target group–adapted mobile intervention that was systematically developed using the BCW. C2go aims to improve drinking habits and the consumption of vegetables and fruit among adolescents and young adults, especially from disadvantaged backgrounds, using a gamification approach.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted within the Competence Cluster for Nutrition and Cardiovascular Health Halle-Jena-Leipzig, which is supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research under grant no. 01EA1411C.

Abbreviations

- APEASE

affordable, practicable, effective, acceptable, side-effects, equity

- BCT

behavior change technique

- BCW

behavior change wheel

- C2go

Challenge to go

- COM-B

capability-opportunity-motivation-behavior

- HAPA

health action process approach

- mHealth

mobile health

- NCD

noncommunicable disease

Additional information on studies 1 and 2.

Behavioral diagnosis to derive what needs to be changed to achieve the target behavior and estimation of feasibility in a dietary mobile app.

Results of studies 1 and 2.

Bringing together behavior change techniques and target group preferences for derivation of app features.

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: AR designed studies 1, 2, and 3, developed the intervention, managed data collection and analysis of studies 1 and 2, and wrote the manuscript. AD codeveloped study 3, managed data collection and analysis of study 3, wrote the respective part of the manuscript, and provided feedback on the manuscript. CB, SL, JG, and CD contributed guidance and consultation throughout the studies and discussed study designs and results. They provided feedback on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. 2014. [2019-07-18]. Global Status Report On Noncommunicable Diseases 2014 https://tinyurl.com/yyxm5ym6.

- 2.Nichols M, Townsend N, Scarborough P, Rayner M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe 2014: epidemiological update. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 7;35(42):2950–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu299.ehu299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Micha R, Peñalvo JL, Cudhea F, Imamura F, Rehm CD, Mozaffarian D. Association between dietary factors and mortality from heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes in the United States. J Am Med Assoc. 2017 Dec 7;317(9):912–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0947. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28267855 .2608221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DGK – Leitlinien - Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kardiologie – Herz. 2012. [2019-07-18]. ESC Pocket Guidelines: Prävention von Herz-Kreislauf-Erkrankungen https://leitlinien.dgk.org/files/PL_Pr%c3%a4vention_Internet_13.pdf.

- 5.Umer A, Kelley GA, Cottrell LE, Giacobbi P, Innes KE, Lilly CL. Childhood obesity and adult cardiovascular disease risk factors: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2017 Dec 29;17(1):683. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4691-z. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-017-4691-z .10.1186/s12889-017-4691-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Global Atlas on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhupathiraju SN, Tucker KL. Coronary heart disease prevention: nutrients, foods, and dietary patterns. Clin Chim Acta. 2011 Aug 17;412(17-18):1493–514. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.04.038. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21575619 .S0009-8981(11)00256-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gan Y, Tong X, Li L, Cao S, Yin X, Gao C, Herath C, Li W, Jin Z, Chen Y, Lu Z. Consumption of fruit and vegetable and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Cardiol. 2015 Mar 15;183:129–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.01.077.S0167-5273(15)00104-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhupathiraju SN, Wedick NM, Pan A, Manson JE, Rexrode KM, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Hu FB. Quantity and variety in fruit and vegetable intake and risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013 Dec;98(6):1514–23. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.066381. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24088718 .ajcn.113.066381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown CM, Dulloo AG, Montani JP. Sugary drinks in the pathogenesis of obesity and cardiovascular diseases. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008 Dec;32(Suppl 6):S28–34. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.204.ijo2008204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bray GA. Energy and fructose from beverages sweetened with sugar or high-fructose corn syrup pose a health risk for some people. Adv Nutr. 2013 Mar 1;4(2):220–5. doi: 10.3945/an.112.002816. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/23493538 .4/2/220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Heart Association. 2017. [2019-07-18]. Diet Drinks and Possible Association With Stroke and Dementia; Current Science Suggests Need for More Research: American Heart Association Stroke Journal Report https://tinyurl.com/yxr65ups .

- 13.Nseir W, Nassar F, Assy N. Soft drinks consumption and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Jun 7;16(21):2579–88. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i21.2579. http://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i21/2579.htm . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2007 Apr;97(4):667–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.083782.AJPH.2005.083782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Max Rubner-Institut. 2008. Ergebnisbericht Teil 1: Nationale Verzehrsstudie Ii: Die Bundesweite Befragung Zur Ernährung Von Jugendlichen Und Erwachsenen https://tinyurl.com/yxg9adoh .

- 16.Schienkiewitz AK, Brettschneider SD, Schaffrath RA. [Overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence in Germany? Cross-section results from KiGGS Wave 2 and Trends] J Health Monit. 2018;3(1):16–23. doi: 10.17886/RKI-GBE-2018-005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borrmann A, Mensink GB, KiGGS Study Group [Fruit and vegetable consumption by children and adolescents in Germany: results of KiGGS wave 1] Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015 Sep;58(9):1005–14. doi: 10.1007/s00103-015-2208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mensink GB, Schienkiewitz A, Rabenberg M, Borrmann A, Richter A, Haftenberger M. Consumption of sugary soft drinks among children and adolescents in Germany. Results of the cross-sectional KiGGS wave 2 study and trends. J Health Monit. 2018;3(1) doi: 10.17886/RKI-GBE-2018-007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung. 2018. Vollwertig Essen Und Trinken Nach Den 10 Regeln Der DGE https://www.dge.de/ernaehrungspraxis/vollwertige-ernaehrung/10-regeln-der-dge/

- 20.Health.gov. 2015. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015-2020 https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/resources/2015-2020_Dietary_Guidelines.pdf .

- 21.Gu X, Tucker KL. Dietary intakes of the US child and adolescent population and their adherence to the current dietary guidelines: trends from 1999 to 2012. FASEB J. 2017;31(1):29.1. https://www.fasebj.org/doi/abs/10.1096/fasebj.31.1_supplement.29.1 . [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008 May;87(5):1107–17. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1107.87/5/1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heuer T, Krems C, Moon K, Brombach C, Hoffmann I. Food consumption of adults in Germany: results of the German national nutrition survey II based on diet history interviews. Br J Nutr. 2015 May 28;113(10):1603–14. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515000744. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25866161 .S0007114515000744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mensink GB, Kleiser C, Richter A. [Food consumption of children and adolescents in Germany. Results of the German health interview and examination survey for children and adolescents (KiGGS)] Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2007;50(5-6):609–23. doi: 10.1007/s00103-007-0222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mensink GB, Heseker H, Stal A, Richter A, Vohmann C, Koch R. Ernährungs-Umschau. 2007. Die Aktuelle Nährstoffversorgung Von Kindern Und Jugendlichen in Deutschland: Ergebnisse Aus Eskimo https://www.ernaehrungs-umschau.de/fileadmin/Ernaehrungs-Umschau/pdfs/pdf_2007/11_07/EU11_636_646.qxd.pdf.

- 26.Bartsch S. Ernährungs-Umschau. 2010. Jugendesskultur https://www.ernaehrungs-umschau.de/fileadmin/Ernaehrungs-Umschau/pdfs/pdf_2010/08_10/EU08_2010_432_438.qxd.pdf.

- 27.Albrecht UV. Federal Ministry of Health (Germany) 2016. Chancen und Risiken von Gesundheits-Apps (CHARISMHA) https://tinyurl.com/y66aspjr .

- 28.Dute DJ, Bemelmans WJ, Breda J. Using mobile apps to promote a healthy lifestyle among adolescents and students: a review of the theoretical basis and lessons learned. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016 May 5;4(2):e39. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3559. http://mhealth.jmir.org/2016/2/e39/ v4i2e39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lunde P, Nilsson BB, Bergland A, Kværner KJ, Bye A. The effectiveness of smartphone apps for lifestyle improvement in noncommunicable diseases: systematic review and meta-analyses. J Med Internet Res. 2018 Dec 4;20(5):e162. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9751. http://www.jmir.org/2018/5/e162/ v20i5e162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curtis KE, Lahiri S, Brown KE. Targeting parents for childhood weight management: development of a theory-driven and user-centered healthy eating app. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015 Jun 18;3(2):e69. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3857. http://mhealth.jmir.org/2015/2/e69/ v3i2e69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.König LM, Sproesser G, Schupp HT, Renner B. Describing the process of adopting nutrition and fitness apps: behavior stage model approach. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018 Mar 13;6(3):e55. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.8261. http://mhealth.jmir.org/2018/3/e55/ v6i3e55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rohde A, Lorkowski S, Dawczynski C, Brombach C. Dietary mobile apps: acceptance among young adults: a qualitative study. Ernahrungs Umschau. 2017;64(2):36–43. doi: 10.4455/eu.2017.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zichermann G, Cunningham C. Gamification By Design: Implementing Game Mechanics In Web And Mobile Apps. Sebastopol, California: O'Reilly Media; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berger V, Schrader U. Fostering sustainable nutrition behavior through gamification. Sustainability. 2016 Jan 12;8(1):67. doi: 10.3390/su8010067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011 Apr 23;6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 .1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwarzer R, Lippke S, Luszczynska A. Mechanisms of health behavior change in persons with chronic illness or disability: the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) Rehabil Psychol. 2011 Aug;56(3):161–70. doi: 10.1037/a0024509.2011-14571-001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin CY, Scheerman JF, Yaseri M, Pakpour AH, Webb TL. A cluster randomised controlled trial of an intervention based on the Health Action Process Approach for increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in Iranian adolescents. Psychol Health. 2017 Dec;32(12):1449–68. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2017.1341516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Storm V, Dörenkämper J, Reinwand DA, Wienert J, de Vries H, Lippke S. Effectiveness of a web-based computer-tailored multiple-lifestyle intervention for people interested in reducing their cardiovascular risk: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2016 Apr 11;18(4):e78. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5147. http://www.jmir.org/2016/4/e78/ v18i4e78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brookie KL, Mainvil LA, Carr AC, Vissers MC, Conner TS. The development and effectiveness of an ecological momentary intervention to increase daily fruit and vegetable consumption in low-consuming young adults. Appetite. 2017 Dec 1;108:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.09.015.S0195-6663(16)30463-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide To Designing Interventions. Croydon, England: Silverback Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Google Play. 2018. [2019-07-17]. Was ich esse App https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=de.aid.android.ernaehrungspyramide&hl=de .

- 42.Kuckartz U. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung. Dritte Edition. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Juventa; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mummah SA, King AC, Gardner CD, Sutton S. Iterative development of Vegethon: a theory-based mobile app intervention to increase vegetable consumption. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016 Aug 8;13:90. doi: 10.1186/s12966-016-0400-z. https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-016-0400-z .10.1186/s12966-016-0400-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou G, Gan Y, Miao M, Hamilton K, Knoll N, Schwarzer R. The role of action control and action planning on fruit and vegetable consumption. Appetite. 2015 Aug;91:64–8. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.03.022.S0195-6663(15)00124-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Achterberg T, de Waal GG, Ketelaar NA, Oostendorp RA, Jacobs JE, Wollersheim HC. How to promote healthy behaviours in patients? An overview of evidence for behaviour change techniques. Health Promot Int. 2011 Jun;26(2):148–62. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daq050. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20739325 .daq050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harkin B, Webb TL, Chang BP, Prestwich A, Conner M, Kellar I, Benn Y, Sheeran P. Does monitoring goal progress promote goal attainment? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol Bull. 2016 Feb;142(2):198–229. doi: 10.1037/bul0000025.2015-47216-001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dusseldorp E, van Genugten L, van Buuren S, Verheijden MW, van Empelen P. Combinations of techniques that effectively change health behavior: evidence from meta-CART analysis. Health Psychol. 2014 Dec;33(12):1530–40. doi: 10.1037/hea0000018.2013-41338-001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van de Ridder JM, Peters CM, Stokking KM, de Ru JA, ten Cate OT. Framing of feedback impacts student's satisfaction, self-efficacy and performance. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2015 Aug;20(3):803–16. doi: 10.1007/s10459-014-9567-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prestwich A, Kellar I, Parker R, MacRae S, Learmonth M, Sykes B, Taylor N, Castle H. How can self-efficacy be increased? Meta-analysis of dietary interventions. Health Psychol Rev. 2014;8(3):270–85. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2013.813729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poínhos R, van der Lans IA, Rankin A, Fischer AR, Bunting B, Kuznesof S, Stewart-Knox B, Frewer LJ. Psychological determinants of consumer acceptance of personalised nutrition in 9 European countries. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110614. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110614 .PONE-D-14-25910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Godinho CA, Alvarez M, Lima ML. Formative research on HAPA model determinants for fruit and vegetable intake: target beliefs for audiences at different stages of change. Health Educ Res. 2013 Dec;28(6):1014–28. doi: 10.1093/her/cyt076.cyt076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kessels LT, Ruiter RA, Brug J, Jansma BM. The effects of tailored and threatening nutrition information on message attention. Evidence from an event-related potential study. Appetite. 2011 Feb;56(1):32–8. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.11.139.S0195-6663(10)00686-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berkovsky S, Hendrie G, Freyne J, Noakes M, Usic K. The HealthierU portal for supporting behaviour change and diet programs. In: Georgiou A, Grain H, Schaper LK, editors. Driving Reform: Digital Health Is Everyone's Business: Selected Papers from the 23rd Australian National Health Informatics Conference. Amsterdam: IOS Press Incorporated; 2015. pp. 15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baranowski MT, Bower PK, Krebs P, Lamoth CJ, Lyons EJ. Effective feedback procedures in games for health. Games Health J. 2013 Dec;2(6):320–6. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2013.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brouwer W, Kroeze W, Crutzen R, de Nooijer J, de Vries NK, Brug J, Oenema A. Which intervention characteristics are related to more exposure to internet-delivered healthy lifestyle promotion interventions? A systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2011 Jan 6;13(1):e2. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1639. http://www.jmir.org/2011/1/e2/ v13i1e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Volpp KG, John LK, Troxel AB, Norton L, Fassbender J, Loewenstein G. Financial incentive-based approaches for weight loss: a randomized trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2008 Dec 10;300(22):2631–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.804. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19066383 .300/22/2631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chung AE, Skinner AC, Hasty SE, Perrin EM. Tweeting to health: a novel mhealth intervention using FitBits and Twitter to foster healthy lifestyles. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2017 Jan;56(1):26–32. doi: 10.1177/0009922816653385.0009922816653385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Samdal GB, Eide GE, Barth T, Williams G, Meland E. Effective behaviour change techniques for physical activity and healthy eating in overweight and obese adults; systematic review and meta-regression analyses. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017 Dec 28;14(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0494-y. https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-017-0494-y .10.1186/s12966-017-0494-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lara J, Evans EH, O'Brien N, Moynihan PJ, Meyer TD, Adamson AJ, Errington L, Sniehotta FF, White M, Mathers JC. Association of behaviour change techniques with effectiveness of dietary interventions among adults of retirement age: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC Med. 2014 Oct 7;12:177. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0177-3. https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-014-0177-3 .s12916-014-0177-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.König LM, Renner B. Colourful = healthy? Exploring meal colour variety and its relation to food consumption. Food Qual Prefer. 2018 Mar;64:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Werch CE, Moore MJ, Bian H, DiClemente CC, Ames SC, Weiler RM, Thombs D, Pokorny SB, Huang IC. Efficacy of a brief image-based multiple-behavior intervention for college students. Ann Behav Med. 2008 Oct;36(2):149–57. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9055-6. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/18800217 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mummah S, Robinson TN, Mathur M, Farzinkhou S, Sutton S, Gardner CD. Effect of a mobile app intervention on vegetable consumption in overweight adults: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017 Dec 15;14(1):125. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0563-2. https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-017-0563-2 .10.1186/s12966-017-0563-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.LeGrand S, Muessig KE, McNulty T, Soni K, Knudtson K, Lemann A, Nwoko N, Hightow-Weidman LB. Epic allies: development of a gaming app to improve antiretroviral therapy adherence among young HIV-positive men who have sex with men. JMIR Serious Games. 2016 May 13;4(1):e6. doi: 10.2196/games.5687. http://games.jmir.org/2016/1/e6/ v4i1e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hebden L, Cook A, van der Ploeg HP, Allman-Farinelli M. Development of smartphone applications for nutrition and physical activity behavior change. JMIR Res Protoc. 2012 Aug 22;1(2):e9. doi: 10.2196/resprot.2205. http://www.researchprotocols.org/2012/2/e9/ v1i2e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Duncan M, Vandelanotte C, Kolt GS, Rosenkranz RR, Caperchione CM, George ES, Ding H, Hooker C, Karunanithi M, Maeder AJ, Noakes M, Tague R, Taylor P, Viljoen P, Mummery WK. Effectiveness of a web- and mobile phone-based intervention to promote physical activity and healthy eating in middle-aged males: randomized controlled trial of the ManUp study. J Med Internet Res. 2014 Jun 12;16(6):e136. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3107. http://www.jmir.org/2014/6/e136/ v16i6e136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Google Services. 2015. [2019-07-19]. Global Connected Consumer Study - Ergebnisse Für Deutschlandine Studie Von TNS Infratest in Kooperation Mit Dem BVDW Und Google https://services.google.com/fh/files/misc/global-connected-consumer-studie-deutschland.pdf.

- 67.Dennison L, Morrison L, Conway G, Yardley L. Opportunities and challenges for smartphone applications in supporting health behavior change: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2013 Apr 18;15(4):e86. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2583. http://www.jmir.org/2013/4/e86/ v15i4e86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nollen NL, Hutcheson T, Carlson S, Rapoff M, Goggin K, Mayfield C, Ellerbeck E. Development and functionality of a handheld computer program to improve fruit and vegetable intake among low-income youth. Health Educ Res. 2013 Apr;28(2):249–64. doi: 10.1093/her/cys099. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22949499 .cys099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carter MC, Burley VJ, Nykjaer C, Cade JE. Adherence to a smartphone application for weight loss compared to website and paper diary: pilot randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2013 Apr 15;15(4):e32. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2283. http://www.jmir.org/2013/4/e32/ v15i4e32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mummah SA, Mathur M, King AC, Gardner CD, Sutton S. Mobile technology for vegetable consumption: a randomized controlled pilot study in overweight adults. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016 May 18;4(2):e51. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.5146. http://mhealth.jmir.org/2016/2/e51/ v4i2e51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee W, Chae YM, Kim S, Ho SH, Choi I. Evaluation of a mobile phone-based diet game for weight control. J Telemed Telecare. 2010;16(5):270–5. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.090913.jtt.2010.090913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Robinson E, Higgs S, Daley AJ, Jolly K, Lycett D, Lewis A, Aveyard P. Development and feasibility testing of a smart phone based attentive eating intervention. BMC Public Health. 2013 Jul 9;13:639. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-639. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-13-639 .1471-2458-13-639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Michie S, West R, Campbell R, Brown J, Gainforth H. ABC of Behaviour Change Theories: An Essential Resource for Researchers, Policy Makers and Practitioners. Croydon: Silverback Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Michie S, Prestwich A. Are interventions theory-based? Development of a theory coding scheme. Health Psychol. 2010 Jan;29(1):1–8. doi: 10.1037/a0016939.2010-00152-001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Short C, Rebar AL, Plotnikoff R, Vandelanotte C. Designing engaging online behaviour change interventions: a proposed model of user engagement. Eur Health Psychol. 2015;17(1):32–8. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Atkins L, Michie S. Designing interventions to change eating behaviours. Proc Nutr Soc. 2015 May;74(2):164–70. doi: 10.1017/S0029665115000075.S0029665115000075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pearson ES. Goal setting as a health behavior change strategy in overweight and obese adults: a systematic literature review examining intervention components. Patient Educ Couns. 2012 Apr;87(1):32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.018.S0738-3991(11)00385-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Burke LE, Conroy MB, Sereika SM, Elci OU, Styn MA, Acharya SD, Sevick MA, Ewing LJ, Glanz K. The effect of electronic self-monitoring on weight loss and dietary intake: a randomized behavioral weight loss trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011 Feb;19(2):338–44. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.208. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.208.oby2010208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Robinson TN. Stealth interventions for obesity prevention and control. In: Dube L, Bechara A, Drewnowski A, LeBel J, James P, Yada RY, editors. Obesity Prevention: The Role of Brain and Society on Individual Behavior. First Edition. Amsterdam: Academic Press; 2011. pp. 319–27. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lisetti C, Yasavur U, Leon C, Amini R, Rishe N, Visser U. Building an On-Demand Avatar-Based Health Intervention for Behavior Change. Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth International Florida Artificial Intelligence Research Society Conference; FLAIRS'12; May 23-25, 2012; Marco Island, Florida. 2012. pp. 175–80. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional information on studies 1 and 2.

Behavioral diagnosis to derive what needs to be changed to achieve the target behavior and estimation of feasibility in a dietary mobile app.

Results of studies 1 and 2.

Bringing together behavior change techniques and target group preferences for derivation of app features.