Abstract

Flores Island, Indonesia, was inhabited by the small-bodied hominin species Homo floresiensis, which has an unknown evolutionary relationship to modern humans. This island is also home to an extant human pygmy population. Here we describe genome-scale single-nucleotide polymorphism data and whole-genome sequences from a contemporary human pygmy population living on Flores near the cave where H. floresiensis was found. The genomes of Flores pygmies reveal a complex history of admixture with Denisovans and Neanderthals but no evidence for gene flow with other archaic hominins. Modern individuals bear the signatures of recent positive selection encompassing the FADS (fatty acid desaturase) gene cluster, likely related to diet, and polygenic selection acting on standing variation that contributed to their short-stature phenotype. Thus, multiple independent instances of hominin insular dwarfism occurred on Flores.

Island Southeast Asia (ISEA) represents a key region for the study of hominin evolution and interaction. Several extinct hominin groups populated this region, and current inhabitants harbor both Neanderthal and Denisovan ancestry in their genomes. Fossil evidence indicates the presence of Homo erectus on Java from ~1.7 million years (Ma) ago to somewhere between 53 and 27 thousand years (ka) ago (1, 2), Homo floresiensis on Flores from 100 to 60 ka ago (3–5), and modern humans in Sulawesi by 40 ka ago (6). Furthermore, the highest Denisovan ancestry is found in this region, in people living east of Wallace’s Line (7), a stark faunal boundary representing the ancient and persistent deep-water separation of the Sunda and Sahul lands. Much of the genetic ancestry of modern ISEA groups derives from the Austronesian expansion, a demographic event that carried genes from mainland Asia 4 to 3 ka ago (8). However, it remains unclear how selection and admixture with archaic hominins in some remote island groups may be related to this expansion and contemporary populations in this region.

The history of hominin presence on Flores Island is particularly enigmatic. Found 400 km east of Wallace’s Line, Flores is home to skeletal remains of the diminutive species H.floresiensis (estimated height of ~106 cm) (3, 4), which inhabited this biogeographical setting from ~0.7 Ma ago until 60 ka ago (5, 9). Archaeological evidence indicates hominin presence on Flores by 1 Ma ago (10). More recent remains of short-statured humans have also been found at cave sites on the island (11). Current Flores inhabitants include a pygmy population living in the village of Rampasasa (12), near the Liang Bua cave where H. floresiensis fossils were discovered (3).

We collected DNA samples from 32 adult individuals from Rampasasa (average height of 145 cm) (Fig. 1A and table S1) (13) and generated genotype data for ~2.5 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (fig. S1). On the basis of family relationships and ancestry inferred from SNP data (table S2 and figs. S2 and S3), we selected 10 individuals for whole-genome sequencing (median depth of 37.8x; genotype concordance >99.8%) (table S3). The sequenced individuals include a trio to facilitate haplotype inference (13), but only nine unrelated individuals were considered for downstream analyses.

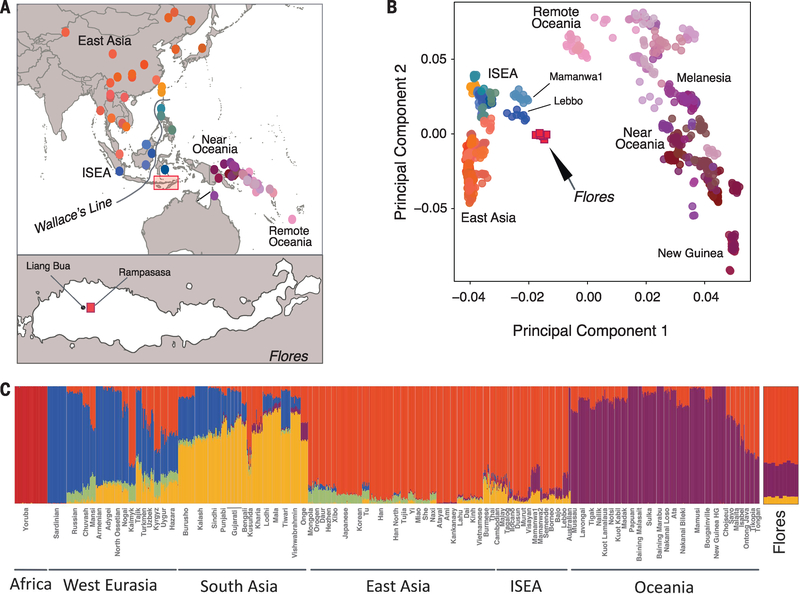

Fig. 1. Sampling location and genomic variation of the Flores pygmies.

(A) Location of Flores pygmy village and populations integrated into the analysis. The inset shows a subset of 85 populations from East Asia (EA), ISEA, and Oceania used for the PCA. The Rampasasa village (red square) is close to the Liang Bua cave, where H. floresiensis fossils were excavated. (B) PCA performed on 85 populations (13). (C) ADMIXTURE results for K = 6 clusters are shown for 96 worldwide populations (13).

To infer population relationships, we integrated our sequencing data with SNP array data from 2507 individuals spanning 225 worldwide populations, as well as sequencing data from Melanesia (13). A principal component analysis (PCA) places the Flores population in close proximity to a cluster of East Asian and ISEA samples, with a notable affinity toward Oceanic populations (Fig. 1B and table S4). Population structure inferred by ADMIXTURE shows that most of the ancestry in the Flores pygmies can be explained by an East Asian–related component and by a smaller New Guinean–related component, shared with Oceanic populations (Fig. 1C and fig. S4). The New Guinean component accounts for 23.2% of Flores ancestry (z-score > 85) (fig. S5) (13).

These results, along with multiple sequential Markovian coalescent inferences of effective population size and divergence times, analyses of inbreeding, and mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosome variation, indicate that the Flores pygmies likely trace their ancestry back to the ancestors of Near Oceanic populations and experienced a recent admixture event with populations of East Asian ancestry (figs. S6 to S11 and tables S4 and S5) (13).

We used a PCA projection method to describe the relationship between the Flores pygmies and archaic hominins (13). Flores individuals exhibit affinity to both Neanderthals and Denisovans, suggesting that they harbor ancestry from both archaic hominins (Fig. 2A). Using F4 ratio statistics, we estimated that the Flores pygmies harbor, on average, 0.8% Denisovan ancestry (z-score > 4) (13), which is higher than the amount for other ISEA populations but lower than that for Oceanic populations. Consistent with previous observations (7), the amount of inferred Denisovan ancestry is positively correlated with proportion of New Guinean ancestry (Pearson’s correlation = 0.97, P < 10−16) (fig. S12) (13).

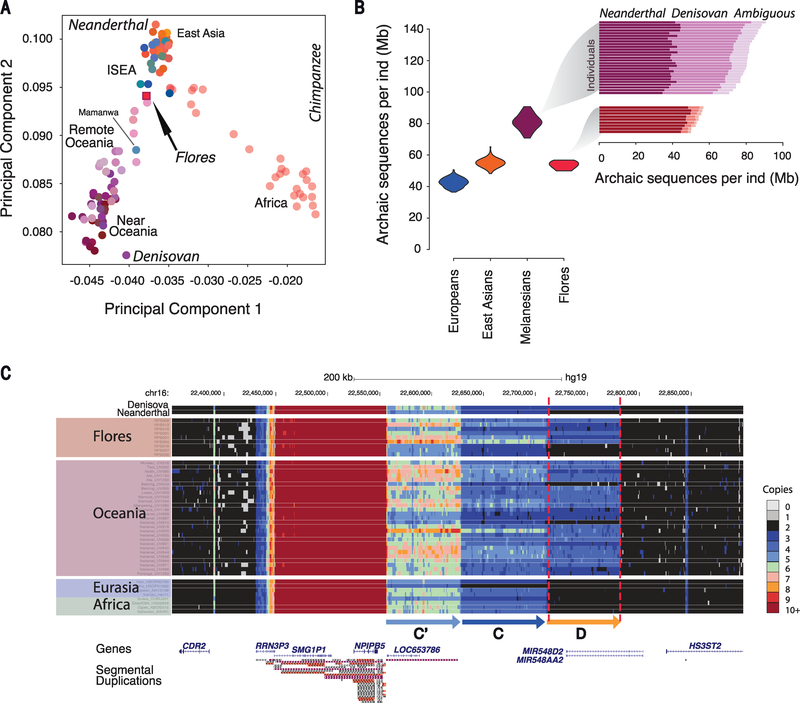

Fig. 2. Archaic hominin ancestry in the Flores pygmies.

(A) PCA to investigate genetic similarities of present-day humans and archaic hominins. Mean values for the top two principal components were plotted for each population. (B) Amounts of total archaic introgressed sequences in 9 Flores pygmies, 27 Melanesians, 103 East Asians, and 91 Europeans. The inset shows amounts of Neanderthal, Denisovan, and ambiguous sequences in Flores and Melanesian individuals. (C) The Denisovan D duplication is present only in Denisovan, Oceanic, and Flores individuals. A panel of worldwide populations is shown, along with the Denisovan and Neanderthal genomes (13). A copy number greater than two (four and three for light and dark blue, respectively) in region D (far right) indicates presence of the duplication.

We identified regions inherited from archaic hominins by applying the S* statistical framework (fig. S13) (13) to 9 Flores, 27 Melanesian, 103 East Asian, and 91 European genomes. On average, we retrieved 53.5 Mb of significant S* sequence in the Flores sample (false discovery rate ≤ 5%) (Fig. 2B). Of this, 47.5 and 4.2 Mb were assigned with high confidence to the Neanderthal and Denisovan groups, respectively, whereas 1.8 Mb were classified as “ambiguous” (for which Neanderthal or Denisovan status cannot be confidently distinguished) (Fig. 2B, inset, and fig. S14). The average amount of Neanderthal sequence per individual (47.5 Mb) among Flores pygmies is intermediate between that among East Asians (54.5 Mb) and Melanesians (40.2 Mb), whereas the average amount of Denisovan sequence was less than that identified in Melanesians (32 Mb) (fig. S14). These data suggest that the source of Denisovan ancestry was localized east of Wallace’s Line and that such ancestry was diluted in Flores by subsequent admixture with Asian populations carrying less (or no) Denisovan ancestry (14).

The S* statistic does not require information from an archaic reference genome and thus can potentially identify sequences from unknown hominin lineages. We searched for signatures of admixture with an unknown archaic hominin source by analyzing significant S* sequences that did not match the Neanderthal or Denisovan genomes (hereafter called “unknown” sequences) (fig. S14). We found no evidence that unknown sequences in Flores are enriched for older or more divergent lineages (figs. S15 and S16) (13), as would be expected if they contained lineages inherited from a more deeply divergent hominin group, such as H. floresiensis or H. erectus. Although it is difficult to exclude very low levels of admixture from such groups given current methodological limitations, our data are inconsistent with substantial levels of ancestry from a deeply divergent hominin lineage.

We analyzed copy number variation (CNV) in the Flores pygmies, along with a panel of diverse modern and archaic human genomes (figs. S17 to S24 and tables S6 and S7) (13). We found 1865 biallelic CNVs in Flores individuals, as well as a common [allele frequency (AF) = 50%], large segmental duplication block (>220 kilo–base pairs; chromosome 16p12.2) that to date has been observed only in Denisovan and Oceanic individuals (AF = 82.6%) (Fig. 2C and fig. S18). Previous work suggests this duplication introgressed from Denisovans into the ancestors of present-day populations in Oceania ~40 ka ago (15).

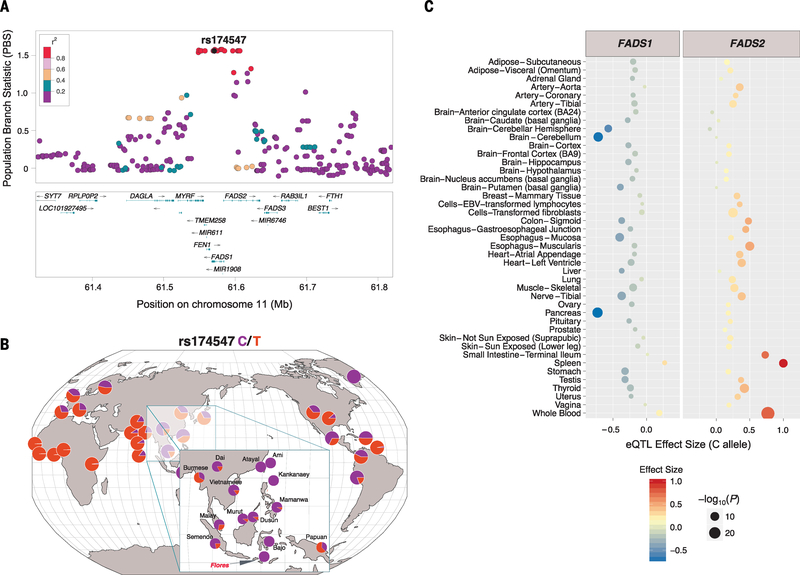

To test hypotheses of recent adaptation, we used the population branch statistic (PBS) to scan for alleles exhibiting strong population-specific structure (13). We identified 2 genomic windows in the top 0.001 percentile (PBS > 1.04) and 10 additional windows in the top 0.01 percentile (PBS > 0.78) of mean genome-wide PBS scores (fig. S25 and table S8). One of the top two regions encompasses the human leukocyte antigen gene complex, a well-known substrate of diversifying selection with a critical role in adaptive immunity (13). The strongest PBS signal, however, extends over a ~74-kb region of chromosome 11 that includes FADS1 and FADS2 (Fig. 3A). These genes encode fatty acid desaturase (FADS) enzymes that catalyze synthesis of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFAs) from plant-based medium chain (MC)–PUFA precursors. Notably, the Flores sample is nearly fixed for an ancestral haplotype (tagged by the C allele of SNP rs174547) in a pattern consistent with a recent selective sweep. In the larger Omni2.5-genotyped sample (n = 21 unrelated individuals), we confirmed a 95% frequency of the ancestral (C) allele of rs174547. Other Southeast Asian populations also carry high frequencies of the ancestral allele (Fig. 3B, inset), consistent with positive selection in their common ancestor, with drift and additional selection in ISEA populations subsequent to their divergence (13).

Fig. 3. Population genetic and functional signatures at the FADS locus.

(A) LocusZoom local Manhattan plot showing individual SNP PBS values spanning the FADS locus. Haplotype-defining SNP rs174547 is shown in dark gray, whereas other SNPs are colored according to pairwise linkage disequilibrium with rs174547 (from East Asian populations from the 1000 Genomes Project). (B) Geography of Genetic Variants map at rs174547. Data from Flores (n = 18 haplotypes), Melanesian (n = 54 haplotypes), and the Greenlandic Inuit (n = 4 haplotypes) populations are overlaid on populations from the 1000 Genomes Project. SNP array data from the Human Origin Dataset are shown in the inset. (C) Multitissue eQTL data from the GTEx (Genotype-Tissue Expression) Project, depicting associations between FADS1 and FADS2 expression and the rs174547 genotype. Effect size is displayed on the x axis and by color, whereas significance is indicated by point sizes.

Supporting functional differences, previous data demonstrate that SNPs defining this haplotype are strongly associated with circulating levels of fatty acids (16) (table S9) and a wide variety of blood phenotypes (17) (table S10). Furthermore, these variants are known expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) of both FADS1 and FADS2 (13, 18, 19). Specifically, the selected (C) allele of rs174547 is associated with up-regulation of FADS2 and down-regulation of FADS1 (20) (Fig. 3C), in turn predicting reduced efficiency of conversion from MC- to LC-PUFA.

Our data add to an emerging body of evidence suggesting that the ancestral and derived haplotypes at the FADS locus have been targeted by independent episodes of positive selection in geographically diverse populations (18, 21–23). Notably, an ancestral haplotype at FADS is nearly fixed in an Inuit population in Greenland (23), potentially in response to climate and a marine diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids. While mirroring our findings from Flores, the adaptive Green-landic Inuit haplotype extends over a broader downstream region encompassing FADS3, potentially reflecting distinct selection events or population-specific patterns of recombination (fig. S26). Although the global history of this locus remains to be clarified, current evidence points to a critical role of FADS as an evolutionary “toggle switch” in response to changing diet.

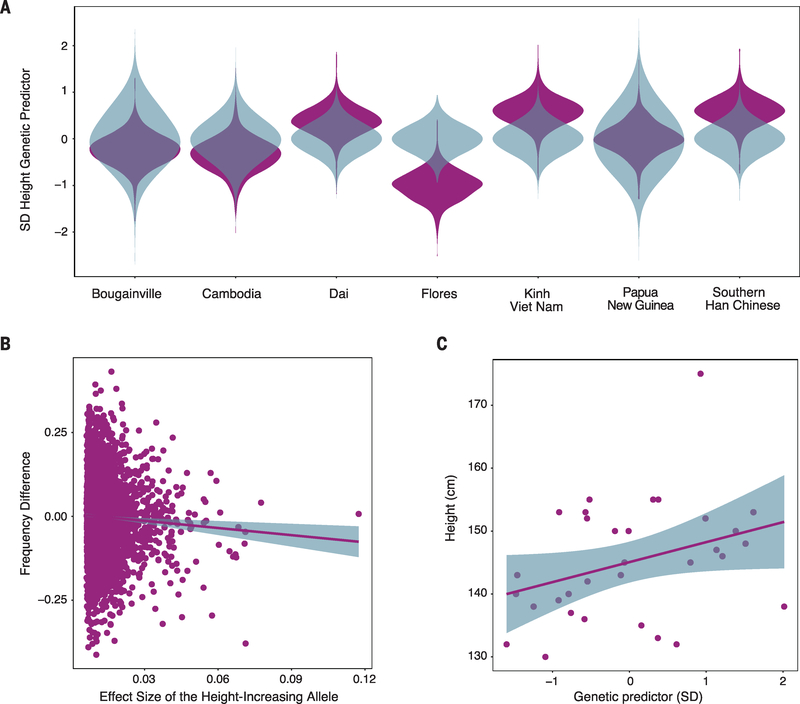

Body size reduction is one of the best-known responses to island environments and is common among mammalian taxa. Examples on Flores include H. floresiensis and the pygmy proboscidean Stegodon. We leveraged our data to test hypotheses about the genetic architecture and evolution of short stature in our Flores sample. If the short-stature phenotype on Flores was a consequence of polygenic selection acting on common variants, we would expect to see higher frequencies of alleles associated with reduced height in other populations (24). We thus performed mixed-linear model association analysis for height in 456,426 individuals of European ancestry to identify height-associated loci, unbiased of population stratification (13).

We find that European height-associated loci are significantly more differentiated between Flores and other neighboring populations than expected under random genetic drift (Fig. 4A). Moreover, the Flores sample is significantly enriched for height-decreasing alleles (test of population genetic differentiation across all SNP sets P < 0.001; correlation of AF differentiation and allele effect size at 4000 alleles of strongest height association: −0.71, t = −3.18, df = 4000, P = 0.002) (Fig. 4B). This result predicts a smaller height for Flores individuals from height-associated alleles discovered in an unrelated panel (Fig. 4A), and we estimate that 36.6% (95% confidence interval: 10.4 to 63.9%) of variation in a genome-wide genetic predictor of height is attributed to mean differences among the populations. Assuming the phenotypic standard deviation (SD) of height in this population is 6 cm and the full heritability is 0.7 (25), then one genetic SD = √0.7 × 6 = 5 cm. Because the genetic predictor explains 8.5% (SE: 3.8%) of phenotypic variance in Flores (Fig. 4C) and the Flores population is 1SD lower than the average of neighboring populations (Fig. 4A), we predict the Flores population to be ~2 cm (√0.085 × 6 = 1.75 cm) shorter in stature than populations in East Asia and Oceania and ~5 cm shorter if the genetic predictor explained 70% of the phenotypic variance. Collectively, these data provide evidence that polygenic selection acting on standing genetic variation was an important determinant of short stature in this Flores pygmy population.

Fig. 4. Polygenic selection for reduced stature in the Flores pygmies.

(A) Comparison of the genome-wide genetic predictor of height from observed genotypes (purple) versus the null model (blue). The Flores panel is significantly enriched for height-reducing alleles (P < 0.001) in a multivariate chi-square test of population genetic differentiation from the expectation under the null model. (B) Frequency differences between the Flores population and neighboring 1000 Genomes Project populations for 4000 genome-wide loci of the strongest association, with height plotted against effect size for the height-increasing allele. The regression slope shown in the figure between the height-increasing effect size and the frequency difference was −0.71 (t = −3.18, P = 0.002), reflecting height-increasing alleles being at lower frequency in the Flores population. (C) Association between height in the Flores population and a genetic predictor of height.

High-coverage genomes provide insights into the history of demographic changes and adaptation in a pygmy population on Flores Island (Indonesia). Although these individuals possess ancestry from both Neanderthals and Denisovans, we found no evidence of admixture with a deeply diverged hominin group. This observation, combined with the evidence that their short-stature phenotype resulted from polygenic selection acting on standing variation, suggests that insular dwarfism arose independently in two separate hominin lineages on Flores Island.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Akey, Green, and Barbujani laboratories, I. Mathieson, J. G. Schraiber, A. Manica, and S. Browning for helpful feedback related to this work. We acknowledge P. Kusuma and other members of the Eijkman Institute for Molecular Biology (EIMB) for providing logistical support in coordinating sample collection.

Funding: This work was supported in part by an NIH grant (R01GM110068) to J.M.A., Searle Scholars Program and Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation grants to R.E.G., Lewis and Clark Fellowship for Exploration and Field Research (American Philosophical Society) and Young Researcher Fellowships for the years 2013 and 2014 (University of Ferrara, Italy) to S.T., European Research Council ERC-2011-AdG_295733 grant (LanGeLin) to G.B., grants from the Australian Research Council (DP160102400) and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (1078037 and 1113400) to P.M.V., and a development grant from the Ministry of Research and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia to H.S. and G.A.P. The UK Biobank research was conducted under project 12514. E.E.E. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Competing interests: J.M.A. is a paid consultant of Glenview Capital. R.E.G. is a paid consultant of Dovetail Genomics and Claret Biosciences.

Data and methodss availability: Whole-genome sequence and SNP data have been deposited into dbGAP with the accession number phs001633.v1.p1. Materials were provided under a material transfer agreement. Individuals interested in obtaining the materials should contact the Eijkman Institute.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Swisher CC III et al. , Science 263, 1118–1121 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swisher CC III et al. , Science 274, 1870–1874 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown P et al. , Nature 431, 1055–1061 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morwood MJ et al. , Nature 431, 1087–1091 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutikna T et al. , Nature 532, 366–369 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aubert M et al. , Nature 514, 223–227 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reich D et al. , Am. J. Hum. Genet 89, 516–528 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu S, Pugach I, Stoneking M, Kayser M, Jin L; HUGO Pan-Asian SNP Consortium, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 109, 4574–4579 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van den Bergh GD et al. , Nature 534, 245–248 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brumm A et al. , Nature 464, 748–752 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verhoeven T, Anthropos 53, 229–232 (1958). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacob T et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 103, 13421–13426 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.See supplementary materials.

- 14.Cooper A, Stringer CB, Science 342, 321–323 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sudmant PH et al. , Science 349, aab3761 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacArthur J et al. , Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D896–D901 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sudlow C et al. , PLOS Med. 12, e1001779 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye K, Gao F, Wang D, Bar-Yosef O, Keinan A, Nat. Ecol. Evol 1, 0167 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buckley MT et al. , Mol. Biol. Evol 34, 1307–1318 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Consortium GTEx, Nature 550, 204–213 (2017).29022597 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathias RA et al. , PLOS ONE 7, e44926 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kothapalli KSD et al. , Mol. Biol. Evol 33, 1726–1739 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fumagalli M et al. , Science 349, 1343–1347 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson MR et al. , Nat. Genet 47, 1357–1362 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang J et al. , Nat. Genet 47, 1114–1120 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.