Abstract

The purpose of this review is to propose a conceptual framework using objectification theory and intersectionality theory to examine social media’s influence on body image and its effect on eating disorder predictors among Latina adolescents. To examine and explore how these effects from social media usage can result in mental health disparities that affect this group, emphasis was placed on how Latina ethnic identity mediates body image. Implications for clinicians and researchers include using strengths-based and culturally specific approaches as protective factors for Latina adolescents to strengthen ethnic identity.

Keywords: eating disorders, social media, Latina adolescents, ethnic identity, intersectionality

Women and girls are disproportionately affected by eating disorders which are often triggered by body dissatisfaction (Ackard, Croll, & Kearney-Cooke, 2002; Cooley, 2001; Stice, 2002; Stice & Shaw, 2002; Velez, Campos, & Moradi, 2015). Eating disorders are prevalent among Latinas, making prevention a priority for this group (Franko et al., 2012). Media portrays beauty ideals that can affect self-body image, eating behaviors, and self-esteem among adolescent Latinas (de Casanova, 2004; Haines, Kleinman, Rifas-Shiman, Field, & Bryn Austin, 2010; Haines & Neumark-Sztainer, 2006). As media use rapidly evolves and social media (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) have become dominant platforms for male and female youth, mainstream beauty production and a consumption culture are available for repetitive access. More research is needed to discern the impact of social media on body image (Andsager, 2014; Fardouly & Vartanian, 2016; Perloff, 2014; Stokes, Clemens, & Rios, 2016). R. J. Williams and Ricciardelli (2014) specifically highlighted the lack of insight into the influence social media has on body image and view of oneself.

Latinx are the largest and fastest growing minority group in the United States however, limited research on eating disorders addresses this group. Despite the belief that Latinx cultures and communities are more accepting of curvier female body types (e.g., Cheney, 2010; Viladrich, Yeh, Bruning, & Weiss, 2009), many U.S. Latinas seek to be thinner (Cheney, 2010). Although a majority of literature on body dissatisfaction focuses on White adolescent girls, research focusing specifically on Latina adolescent girls is increasing. Latinas and White women have similar rates of body dissatisfaction (Cachelin, Veisel, Barzegarnazari, & Striegel-Moore, 2000; Cheney, 2010; Schooler & Daniels, 2014; Shaw, Ramirez, Trost, Randall, & Stice, 2004; Velez et al., 2015). Low self-esteem is reciprocally predictive of body dissatisfaction and perceptions of negative body image, which may lead to eating disorders among adolescent girls and women (Edwards George & Franko, 2010; Xanthopoulos et al., 2011).

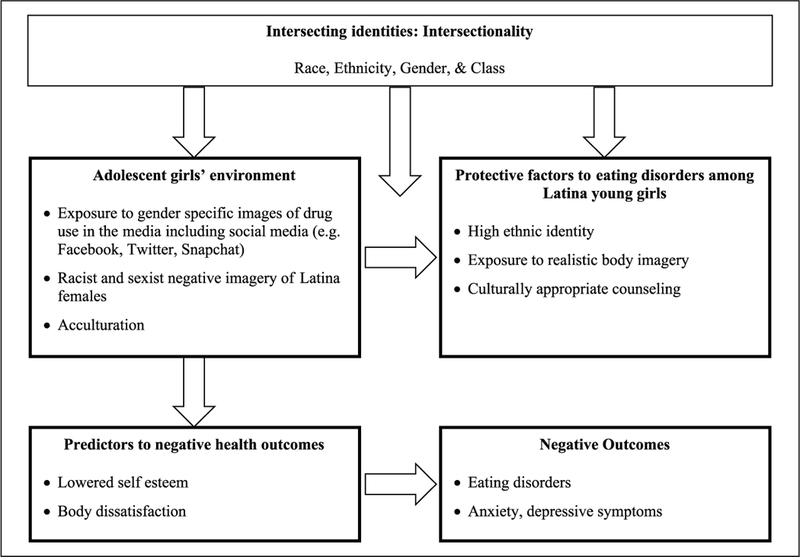

Due to multiplicative social identities of being female and a member of racial/ethnic minorities, Latina adolescents experience intersecting forms of oppression leading to poorer preventable health outcomes. Due to their marginalized status, researchers often ignore Latina adolescents and minimize their outcomes. Here, we provide a conceptual framework that can guide prevention researchers and clinicians in how to address body dissatisfaction among Latina girls. First, we discuss key indicators of eating-disorder symptomatology and address possible causes of symptoms. We then present a conceptual model, guided by objectification and intersectionality theories, which we recommend be used for intervention development in addressing body dissatisfaction among Latina adolescent girls. Objectification theory documents the links of sexual objectification with body imagery and psychological symptomatology among girls. Intersectionality highlights the racial and sexist ideologies that contribute to overly sexualized imagery of girls of color and promotes ethnic identity as a key factor in the relationship between body image and eating disorders among Latina adolescent girls and women.

Theoretical Framework

Objectification Theory

Fredrickson and Roberts (1997) first proposed objectification theory as a framework to understand the experiential consequences of being female in a culture that sexually objectifies the female body. Self-objectification begins when women begin viewing themselves as objects to be looked at and evaluated on the basis of their appearance (Carr & Szymanski, 2011; Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). The theory assumes that, due to women’s gender-role socialization, women’s unhealthy culture manifests in a variety of internalized mental health issues (Levesque, 2011). Objectification theories explain mental health and body dissatisfaction issues with women of color and women from marginalized groups including African American women (e.g., Watson, Ancis, White, & Nazari, 2013) and Muslim American women (Tolaymat & Moradi, 2011). Although objectification theory research with Latina girls and women is limited, findings support explaining sexual objectification among this population.

Research on media studies highlighted the risks of women’s self-objectification because various forms of media offer unrealistic perspectives on the average person’s appearance (Levesque, 2011). Internalization of unrealistic perspectives can cause girls and women to judge their appearances, manifesting in anxiety, body shaming, drug use, and eating disorders (Levesque, 2011). Two studies with Latina women supported the interrelationship of internalization, body surveillance, body shaming, and eating-disorder symptomatology (Boie, Lopez, & Sass, 2013), which did not differ significantly between Latinx and European American participants (Boie et al., 2013). Latina women have the same levels of body dissatisfaction and eating-disor-der symptomatology as White women, although researchers primarily focused on White women (Kimber, Couturier, Georgiades, Wahoush, & Jack, 2015).

Intersectionality Theory

Intersectionality theory aids in understanding the multiplicative identities of Latinas that contribute to disparities in eating-disorder symptomatology. Intersectionality theory examines multiple dimensions of identities and social locations and how they intersect (Crenshaw, 1991). Intersectionality theory specifically acknowledges people’s social location that places them at risk, describing how multiple forms of oppression can affect individuals and families, leading to barriers in achieving positive health outcomes (Brooks, Bowleg, & Quina, 2010; Dhamoon, 2011). Researchers often view salient contextual variables—race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status/class, education level, and ability— as separate sociocultural demographic variables that rarely influence one another. Researchers suggested that an individual’s multiple identities interact and intersect to shape personal experiences and form “intersecting oppressions … that work together to produce injustice” (Collins, 2000, p. 18).

Eating Disorders

Perceptions of an ideal body can vary by age, but body-image dissatisfaction among adolescents is a strong predictor of dysfunctional eating behaviors such as dieting, purging, and binge eating (Ayala, Mickens, Galindo, & Elder, 2007). Eating disorders consistently affect several million people, but mostly affect women between 12 and 35 (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2017). The three most common eating disorders are anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and binge-eating disorder. People are diagnosed with AN when they weigh at least 15% less than the normal healthy weight expected for their height (APA, 2017). Typical behaviors associated with AN include limiting food intake, intense fear of gaining weight, problems with body image, and denial of low body weight. Individuals with BN may go unnoticed because signs are not as physically noticeable as with AN. Individuals with BN can be slightly underweight, normal weight, or overweight (APA, 2017). Individuals with BN binge eat frequently, and the fear of weight gain prompts them to purge by vomiting or using a laxative. They tend to repeat this cycle several times a week or, in serious cases, several times a day.

Unlike with BN, individuals with a binge-eating disorder tend not to purge after they eat. Binge-eating disorder involves a high frequency of overeating during a specific period (at least once a week for 3 months). Those individuals who suffer from binge-eating disorder along with overeating also experience a lack of control, associated with three or more of the following: eating more rapidly than normal, eating until feeling uncomfortably full, eating large amounts of food when not feeling physically hungry, eating alone because of feeling embarrassed by how much one is eating, or feeling disgusted with oneself, depressed, or guilty (APA, 2017).

Eating Disorders Among Young Latina Adolescents

Eating-related problems were lower among ethnic-minority females than Whites (Cachelin, Phinney, Schug, & Striegel-Moore, 2006; Cheney, 2010), though few studies examined eating disorders among diverse populations (e.g., Ayala et al., 2007; Cachelin et al., 2000; Granillo, Jones-Rodriguez, & Carvajal, 2005; Wildes, Emery, & Simons, 2001); researchers found significant differences in types of eating disorders among ethnic minorities. A higher percentage of Latinas suffered from BN (29% compared with 12% among Caucasians, 17% among African Americans, and 5% among Asians; Cachelin et al., 2000). Adult Latina women are equally as likely as White women to develop eating disorders (Wildes et al., 2001). Furthermore, Latina adolescent girls report more diuretic and laxative use than girls from all other ethnic groups (Ayala et al., 2007). However, little has been revealed to guide clinicians on how to identify risk and protective factors among this group.

Body Image

Body image means the physical attributes an individual possesses and their perception of those attributes in comparison of those around them (Williams & Currie, 2000). Attitudes toward and representations of physical attributes often influence adolescents’ body image, central to their developing self-concept and significantly impacting adjustment (Williams & Currie, 2000). Body image is a multidimensional construct influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors (Borzekowski & Bayer, 2005). Body imagery can form perceptual attitudes among individuals, often influenced by historical, civilizing, societal, individual, and genetic factors in a population (Manzoor & Shahed, 2015).

Similar to African American girls (Opara, 2018), the media often portrays Latina female adolescents and women as overly sexual beings (Velez et al., 2015). Due to this misconception, stereotypes form and negatively affect the views of Latina adolescents. Latina girls and women are often expected to be voluptuous, with large breasts (Romo, Mireles-Rios, & Hurtado, 2015). Such imagery often aligns with being overly sexual, whereas the thin ideal White body frame is often view as innocent and modelesque (Romo et al., 2015). This conflict in media imagery can be detrimental for Latina girls who must negate imagery that views them negatively while admiring unrealistic and sometimes unattainable body imagery. Exposure to sexually objectifying media aligns with poorer body image among Latina adolescents (e.g., Schooler & Daniels, 2014). Because the Internet is easily accessible, young women may be consistently exposed to images that portray mainstream beauty (Williams & Ricciardelli, 2014). Because realistic and unrealistic images are fully accessible, young women may become desensitized to imagery and normalized to the notion of aspiring to obtain unrealistic images of beauty (Williams & Ricciardelli, 2014).

Body Image and Social Media

Adolescent girls are more likely to cite specific celebrities as having their ideal body image, although young women acknowledge they possess different bodies than their beauty role models (Grogan, 2012). When adolescent girls make unfavorable comparisons with media images, they are less satisfied with how they look and have lower self-esteem and increased body dissatisfaction (Cheney, 2010; Grogan, 2012; Stice & Shaw, 2002). Social media, unlike traditional media, offers an online environment filled with celebrities and pictures of contemporary and everyday peers found in TV programs and magazines (Williams & Ricciardelli, 2014). Social media is “the media of one’s peers” (Perloff, 2014), comprising an online environment that allows followers to experience many opportunities to compare themselves with their peers. The extent and effects of these comparisons have not yet been thoroughly examined, along with their effects on Latina identity, body image, eating disorders, and psychological outcomes. Furthermore, media representations of Latina women, family emphasis on weight, and typical foods eaten may constitute unique risk factors for body dissatisfaction and dysfunctional eating in this group (Edwards George & Franko, 2010).

Conceptual Model for Latina Adolescents

Eating-Disorder Predictors

Understanding eating-disorder symptomology among Latinas is essential to ensure disparities diminish. Our conceptual framework (see Figure 1) high-lights three key risk factors for eating disorders: self-esteem, body dissatisfaction, and social media.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model of eating-disorder symptomatology outcomes for Latina female adolescents.

Self-esteem.

Self-esteem is a psychological concept referencing a person’s evaluation of self-worth (Martin-Albo, Nunez, Navarri, & Grijalvo, 2007). A person with low self-esteem may feel their life is not worthwhile or may lack pride. Someone with low self-esteem, who has a negative view of themselves, will be more likely to negatively evaluate their body and may experience body dissatisfaction.

Body dissatisfaction.

Body dissatisfaction refers to negative subjective evaluations of one’s physical body, such as figure, weight, stomach, and hips (Stice & Shaw, 2002). Individuals with high body dissatisfaction will be at higher risk of eating disorders because they are likely to seek changes to their bodies by taking extreme measures: reducing calorie intake or participating in self-induced purging (Kwan, Gordon, & Minnich, 2018; Stice & Shaw, 2002; Thompson & Stice, 2001). Body dissatisfaction should not be confused with body distortion, which occurs when one views their body as significantly larger it is (Stice & Shaw, 2002; Thompson & Stice, 2001). Despite the belief that Latinx cultures and communities are more accepting of women’s curvier body types (e.g., Franko, Becker, Thomas, & Herzog, 2007; Viladrich et al., 2009), many young Latinas nonetheless seek to be thinner (e.g., Viladrich et al., 2009). Latina and European American women experience comparable levels of body dissatisfaction and eating-disorder symptomatology (Frederick, Forbes, Grigorian, & Jarcho, 2007; Grabe & Hyde, 2006; Shaw et al., 2004).

Social media, self-esteem, and body dissatisfaction.

Among social-media users, self-esteem may directly relate to the valence of responses received about information posted on one’s personal social-media page (i.e., positive feedback led to positive self-esteem and negative feedback led to negative self-esteem). Individuals with a negative-feedback-seeking style who received a high number of comments on Facebook were more likely to report dysfunctional eating attitudes and weight/shape concerns (Hummel & Smith, 2015).

During the developmental phase of adolescence, where self-esteem is integral, negative perceptions of one’s body image link to lower self-esteem (O’Dea, 2012; Williams & Currie, 2000). Body dissatisfaction is a risk factor for low self-esteem that can lead to eating disturbances (Smolak, 2012). Extreme discontentment with one’s body may accompany dysfunctional eating patterns and pathways toward depression (Borzekowski & Bayer, 2005).

Acculturation.

Contextualizing adolescent Latina body-image development requires an understanding of mainstream body ideals and an understanding of Latinx cultural values and the process by which Latina girls navigate between them (Schooler, 2008). Acculturative stress references the strain many minority groups experience as a result of inconsistencies between expectations of their own ethnic culture and that of the dominant group. Acculturation levels span the borders between mainstream body ideals and Latinx cultural values (Cachelin et al., 2006; Cachelin et al., 2000; Kwan et al., 2018; Schooler & Daniels, 2014). Acculturative stress may occur when one is attempting to learn the language and social norms of the dominant culture. Those who are not acculturated may experience greater acculturative stress because as they learn the cultural patterns of the new society, they realize how different they are from their own (Cachelin et al., 2006; Cachelin et al., 2000; Kwan et al., 2018; Schooler & Daniels, 2014; Umana- Taylor, Diversi, & Fine, 2002). Latina girls who are more acculturated into Western culture may internalize the dominant thin ideal (Schooler, 2008). Because this ideal is largely unattainable for girls of all ethnicities, girls who are more acculturated may feel worse about their own bodies than those who endorse a Latinx body ideal.

Ethnic Identity as a Protective Factor

Ethnic identity.

Ethnic identity refers to self-identification with a specific ethnic group; the sense of belonging and attachment to such a group; the perceptions, behaviors, and feelings one has, due to such membership; and involvement in the cultural and social practices of the group (Phinney, 1996). Latinas often use their immediate social environments to form opinions, ideas, and views about themselves when forming their own identity (Acevedo-Polakovich, Chavez-Korell, & Umana-Taylor, 2013; Padilla & Perez, 2003). Ethnic identity is the awareness and knowledge of an individual’s ethnic membership that may combine with shared values and attitudes of other members of one’s ethnic group (Phinney, 1996). Researchers are identifying an inverse association between ethnic identity and risky behavior. Thus, strengthening ethnic identity in Latina young women may be an effective strategy to promote healthy and positive behaviors.

Body dissatisfaction and self-esteem strongly correlate, especially during the adolescence developmental phase (Smolak, 2012; Williams & Currie, 2000). Although findings on the effect of acculturation on body image have been mixed, findings on positive ethnic-identity development do serve as a buffer for higher self-esteem (Umana-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen, & Guimond, 2009). Identity development is crucial during adolescence. Ethnic identity is a significant protective factor for minority youth.

Ethnic identity and eating disorders.

Latina women and girls with high ethnic identity can be protected against eating disorders, low self-esteem, and body dissatisfaction because of their ethnic-group acceptance of larger body shapes (Cachelin et al., 2006; Cachelin et al., 2000; Schooler, 2008; Schooler & Daniels, 2014; Umana-Taylor et al., 2002). Latinas may experience acculturative stress as a result of discrepancies between their own ethnic body ideal and the body ideal of U.S. dominant society. Furthermore, acculturative stress increases eating-disorder predictors such as low-self-esteem and body dissatisfaction.

In Latina adolescents, it is essential to view social media and its association with eating-disorder symptomatology in the context of ethnic identity. Cultural norms and body imagery favor a thin White female (McCracken, 2014). A focus on ethnic identity references how beauty production and consumption reinforce the “virtual economy of beauty privilege; an exclusive set of beauty standards that have been shaped by years of global and regional racial and national privilege culture and power” (McCracken, 2014).

Implications

Future studies should explore intersectional frameworks to understand unique attributes, risks, and protective factors of specific populations. An intersectional approach and language for clinicians and researchers will avoid the notion of homogeneous treatment options and Eurocentric intervention modalities that solely focuses on eating-disorder symptomatology among White women. Eating problems are not only “gendered experiences of appearance” but are a coping strategy for various traumas including “sexual abuse, racism, classism, sexism, heterosexism and poverty” (Thompson, 1992). Future researchers should study the intersectionality of race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status/class, education level, and ability, often viewed as separate sociocultural demographic variables. Eating-disorder researchers should consider the implications of exposure to unrealistic and unattainable in social media and how they affect young girls. As such images become more prevalent, young women may become increasingly desensitized and pay less attention to the content of such messages, causing little effect (Williams & Ricciardelli, 2014). Researchers should consider such exposure in conjunction with intersectional variables to understand body image, eating-disorder pathology, effective health promotion, help-seeking behaviors, and treatment options for the Latinx community.

Quantitative and qualitative researchers can seek to understand experiences of Latina girls and women that contribute to their marginalized status and their susceptibility to eating disorders based on body distortion. Using social media as a prevention method can encourage researchers to engage in content analysis, allowing researchers to visually quantify the daily images to which Latina girls are exposed while online. Qualitative tools like PhotoVoice are useful in giving Latina girls a platform and voice to discuss their experiences and interactions with body distortions and social media. Often, eating-disorder-prevention programs that exist typically target reducing eating disorders without acknowledging societal views of Latinas and how visuals can negatively affect their view. Extant prevention programs build on etiologic models that propose sociocultural pressure lead to internalization of the thin ideal, resulting in body dissatisfaction, dieting, and negative affect, thereby increasing eating-disorder risk. Through an intersectional lens, clinicians need to be aware of cultural values that are important to Latinas. Latinx families promote traditional and conservative values (e.g., respect, religion, and spirituality) and specific cultural values (e.g., familismo), which emphasize the centering of family. Because Latinas and their families are culturally diverse and are not a homogeneous group, clinicians should incorporate family-based and culture-specific modes of intervention when working with young Latina women who are at risk of dysfunctional eating. Examination of diverse yet unique cultural values among Latinas and their families is essential to understand the risk factors that may contribute to the development of body dissatisfaction and eating disorders (Diaz, Mainous, & Pope, 2007).

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The first author with funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse T 32 Training Grant (5T32 DA07233).

Author Biographies

Ijeoma Opara, PhD, MSW, MPH, is an assistant professor of Social Work at Stony Brook University and a visiting faculty fellow at Yale University School of Public Health. Her research interests predominately focuses on gender and race-specific gender disparities, HIV/AIDS and substance abuse prevention among Black and Hispanic female adolescents.

Noemy Santos is a social work coordinator at Columbia University College of Dental Medicine. She received her master’s degree in Social Work concentrating in Advanced Social Work Practice from Columbia University. She also holds a Master’s of Science in Integrated Marketing Communications from Lasell College, in Newton, MA. Her research interests focuses on health and mental health care advocacy and access for minority communities.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note

Points of view, opinions, and conclusions in this paper do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Government.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Acevedo-Polakovich ID, Chavez-Korell S, & Umana-Taylor AJ (2013). U.S. Latinas/os’ ethnic identity: Context, methodological approaches, and considerations across the life span. The Counseling Psychologist, 42, 154–169. doi: 10.1177/0011000013476959 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ackard DM, Croll JK, & Kearney-Cooke A (2002). Dieting frequency among college females: Association with disordered eating, body image, and related psychological problems. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 52, 129–136. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00269-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2017). What are eating disorders? Retrieved from https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/eating-disorders/what-are-eating-disorders

- Andsager JL (2014). Research directions in social media and body image. Sex Roles, 71, 407–413. doi: 10.1007/s11199-014-0430-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala GX, Mickens L, Galindo P, & Elder JP (2007). Acculturation and body image perception among Latino youth. Ethnicity & Health, 12, 21–41. doi: 10.1080/13557850600824294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boie I, Lopez AL, & Sass DA (2013). An evaluation of a theoretical model predicting dieting behaviors: Tests of measurement and structural invariance across ethnicity and gender. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 46, 114–135. [Google Scholar]

- Borzekowski DLG, & Bayer AM (2005). Body image and media use among adolescents. Adolescent Medicine Clinics, 16, 89–313. doi: 10.1016/j.adme-cli.2005.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks KD, Bowleg L, & Quina K (2010). Minority sexual status among minorities In Loue S (Ed.), Sexualities and identities of minority women (pp. 41–63). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM, Phinney JS, Schug RA, & Striegel-Moore RH (2006). Acculturation and eating disorders in a Mexican American community sample. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 340–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00309.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM, Veisel C, Barzegarnazari E, & Striegel-Moore RH (2000). Disordered eating, acculturation, and treatment-seeking in a community sample of Hispanic, Asian, Black, and White women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24, 244–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb00206.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carr ER, & Szymanski DM (2011). Sexual objectification and substance abuse in young adult women. The Counseling Psychologist, 39, 39–66. doi: 10.1177/0011000010378449 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney A (2010). “Most girls want to be skinny”: Body (dis)satisfaction among ethnically diverse women. Qualitative Health Research, 21, 1347–1359. doi: 10.1177/1049732310392592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH (2000). Gender, black feminism, and black political economy. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 568, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley E (2001). Body image and personality predictors of eating disorder symptoms during the college years. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 30, 28–36. doi: 10.1002/eat.1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women. Stanford Law Review, 43, 1241–1299. de [Google Scholar]

- Casanova EM (2004). “No ugly women”: Concepts of race and beauty among adolescent women in Ecuador. Gender & Society, 18, 287–308. doi: 10.1177/0891243204263351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhamoon RK (2011). Considerations on mainstreaming intersectionality. Political Research Quarterly, 64, 230–243. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz VA, Mainous AG III, & Pope C (2007). Cultural conflicts in the weight loss experience of overweight Latinos. International Journal of Obesity, 31, 328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards George JB, & Franko DL (2010). Cultural issues in eating pathology and body image among children and adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 35, 231–242. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fardouly J, & Vartanian LR (2016). Social media and body image concerns: Current research and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 9, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franko DL, Becker AE, Thomas JJ, & Herzog DB (2007). Cross-ethnic differences in eating disorder symptoms and related distress. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40, 156–164. doi: 10.1002/eat.20341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franko DL, Coen EJ, Roehrig JP, Rodgers RF, Jenkins A, Lovering ME, & Cruz SD (2012). Considering J. Lo and Ugly Betty: A qualitative examination of risk factors and prevention targets for body dissatisfaction, eating disorders, and obesity in young Latina women. Body Image, 9, 381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick DA, Forbes GB, Grigorian KE, & Jarcho JM (2007). The UCLA Body Project I: Gender and ethnic differences in self-objectification and body satisfaction among 2,206 undergraduates. Sex Roles, 57, 317–327. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, & Roberts T (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental helth risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grabe S, & Hyde JS (2006). Ethnicity and body dissatisfaction among women in the United States: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 622–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granillo T, Jones-Rodriguez G, & Carvajal SC (2005). Prevalence of eating disorders in Latina adolescents: Associations with substance use and other correlates. Journal of Adolescent Health, 36, 214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan S (2012). Body image development In Cash TF (Ed.), Encyclopedia of body image and human appearance (pp. 201–206). London, England: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haines J, Kleinman KP, Rifas-Shiman SL, Field AE, & Bryn Austin S (2010). Examination of shared risk and protective factors for overweight and disordered eating among adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 164, 336–343. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines J, & Neumark-Sztainer D (2006). Prevention of obesity and eating disorders: A consideration of shared risk factors. Health Education Research, 21, 770–782. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel AC, & Smith AR (2015). Ask and you shall receive: Desire and receipt of feedback via Facebook predicts disordered eating concerns. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48, 436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber M, Couturier J, Georgiades K, Wahoush O, & Jack SM (2015). Ethnic minority status and body image dissatisfaction: A scoping review of the child and adolescent literature. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 17, 1567–1579. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0082-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan MY, Gordon KH, & Minnich AM (2018). An examination of the relationships between acculturative stress, perceived discrimination, and eating disorder symptoms among ethnic minority college students. Eating Behaviors, 28, 25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque RJR (2011). Objectification theory In Levesque RJR (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 24–38). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor H, & Shahed S (2015). Gender differences in young adults’ body image and self-esteem. Pakistan Journal of Women’s Studies, 22, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Albo J, Núñez JL, Navarro JG, & Grijalvo F (2007). The rosenberg self-esteem scale: Translation and validation in university students. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 10, 458–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken AB (2014). The beauty trade: Youth, gender, and fashion globalization. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dea JA (2012). Body image and self-esteem In Cash TE (Ed.), Encyclopedia of body image and human appearance (pp. 141–147). Oxford, UK: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Opara I (2018). Examining African American parent-daughter HIV risk communication using a Black feminist-ecological lens: Implications for intervention. Journal of Black Studies, 49, 134–151. doi: 10.1177/0021934717741900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla AM, & Perez W (2003). Acculturation, social identity, and social cognition: A new perspective. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25, 35–55. doi: 10.1177/0739986303251694 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perloff RM (2014). Social media effects on young women’s body image concerns: Theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research. Sex Roles, 71, 363–377. doi: 10.1007/s11199-014-0384-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS (1996). Understanding ethnic diversity: The role of ethnic identity.American Behavioral Scientist, 40, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Romo LF, Mireles-Rios R, & Hurtado A (2015). Cultural, media, and peer influences on body beauty perceptions of Mexican American adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Research, 31, 474–501. doi: 10.1177/0743558415594424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schooler D (2008). Real women have curves: A longitudinal investigation of TV and the body image development of Latina adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 23, 132–153. doi: 10.1177/0743558407310712 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schooler D, & Daniels EA (2014). “I am not a skinny toothpick and proud of it”: Latina adolescents’ ethnic identity and responses to mainstream media images. Body Image, 11, 11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw H, Ramirez L, Trost A, Randall P, & Stice E (2004). Body image and eating disturbances across ethnic groups: More similarities than differences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18, 12–18. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolak L (2012). Risk and protective factors in body image problems: Implications for prevention In McVey GL, Levine MP, Piran N, & Ferguson HB (Eds.), Preventing eating-related and weight-related disorders: Collaborative research, advocacy, and policy change (pp. 39–46). Waterloo, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E (2002). Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 825–848. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.128.5.825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, & Shaw HE (2002). Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: A synthesis of research findings. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53, 985–993. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00488-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes DM, Clemens CF, & Rios DI (2016). Brown beauty: Body image, Latinas, and the media. Journal of Family Strengths, 16, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson BW (1992). “A way outa no way”: Eating problems among African- American, Latina, and White Women. Gender & Society, 6, 546–561. doi: 10.1177/089124392006004002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J, & Stice E (2001). Thin-ideal internalization: Mounting evidence for a new risk factor for body-image disturbance and eating pathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 181–183. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tolaymat LD, & Moradi B (2011). U.S. Muslim women and body image: Links among objectification theory constructs and the hijab. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Diversi M, & Fine MA (2002). Ethnic identity and self-esteem of Latino adolescents: Distinctions among the Latino populations. Journal of Adolescent Research, 17, 303–327. [Google Scholar]

- Umana-Taylor A, Gonzales-Backen M, & Guimond A (2009). Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity: Is there a developmental progression and does growth in ethnic identity predict growth in self-esteem? Child Development, 80, 391–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01267.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velez BL, Campos ID, & Moradi B (2015). Relations of sexual objectification and racist discrimination with Latina women’s body image and mental health. The Counseling Psychologist, 43, 906–935. doi: 10.1177/0011000015591287 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viladrich A, Yeh M, Bruning N, & Weiss R (2009). “Do real women have curves?” Paradoxical body images among Latinas in New York City. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 11, 20–28. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9176-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson LB, Ancis JR, White DN, & Nazari N (2013). Racial identity buffers African American women from body image problems and disordered eating. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37, 337–350. [Google Scholar]

- Wildes JE, Emery RE, & Simons AD (2001). The roles of ethnicity and culture in the development of eating disturbance and body dissatisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 21, 521–551. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00071-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM, & Currie C (2000). Self-esteem and physical development in early adolescence: Pubertal timing and body image. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 20, 129–149. doi: 10.1177/0272431600020002002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RJ, & Ricciardelli LA (2014). Social media and body image concerns: Further considerations and broader perspectives. Sex Roles, 71, 389–392. doi: 10.1007/s11199-014-0429-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulos MS, Borradaile KE, Hayes S, Sherman S, Vander Veur S, Grundy KM, … Foster GD (2011). The impact of weight, sex, and race/ ethnicity on body dissatisfaction among urban children. Body Image, 8, 385–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]