Abstract

Objective: Health care providers and patients in the United States have limited experience with acupuncture. A 2007 U.S. Health survey showed that 6.5% of people reported ever using acupuncture and that most them sought relief from pain. Yet, acupuncture was also used as a preventive modality to promote overall health. This study was conducted to determine if a single training session of Battlefield Acupuncture (BFA) was effective and how the session influenced residents' opinions on incorporating BFA training into residency programs.

Materials and Methods: This study was conducted at a single, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation residency program with 18 PGY2–PGY4 level residents. They were given 3-hour didactic lecture by a certified BFA instructor and then a hands-on demonstration. During the demonstration, each participant verified that he or she knew how to place 5 BFA needles. The participants were also surveyed about incorporating BFA training into residency programs.

Results: After the training, 12 of the 18 participants responded to the survey. A majority of those who responded disagreed that their choice for a specific residency program would be affected by whether the program offered BFA certification. More participants than not recommended incorporating BFA into other residency program curricula. Most participants stated that that a one-time didactic and training session was adequate for learning BFA.

Conclusions: Resident-physicians training in BFA techniques is effective. Residents had favorable attitudes toward this treatment and a minority intended to use the technique in their practice. BFA training can be incorporated easily in residency curricula.

Keywords: Battlefield Acupuncture, auriculotherapy, auricular acupuncture

Introduction

Acupuncture has been utilized for millennia as a treatment modality for a variety of medical conditions.1 Although acupuncture is more common in Asia and parts of Europe, Western medicine had not embraced acupuncture's value until around the mid-twentieth century, when this modality became more commonplace in the armamentarium of the practicing physician.1 Along with health care providers, patients in the United States have limited experience with acupuncture. A 2007 U.S. Health survey indicated that 6.5% of people had reported ever using acupuncture and that most of these individuals were seeking relief from pain. However, acupuncture was also being used as a preventive modality to promote overall health.2

Auricular therapy or auriculotherapy and its principles are both based on Traditional Chinese Medicine and acupuncture, along with neurologic reflex therapy, which were discovered in Europe.3 The origins of auriculotherapy go back thousands of years to the early Chinese and were based on the presence of specific acupuncture points located on the ear that, when treated, gave relief to patients who had a variety of medical illnesses.3

Auricular acupuncture was first popularized by a French physician, Paul Nogier, MD, in the 1950s, when he was able to work out a complete cartography of the ear, establishing auricular zones that corresponded to specific body areas. Dr. Nogier's findings began with his observation of successful treatment of sciatica in patients who underwent cauterization of the lower root of each patient's ear antihelix. He confirmed the findings after cauterizing his own ear and later suggested that the antihelix specifically corresponded with the spinal region of the human body.4 Dr. Nogier then went on to treat specific points on the ear with acupuncture and described an intricate mapping of the ear—based on neuroanatomy, experimentation, and embryology—that has been a cornerstone in the advancement of auricular acupuncture.4

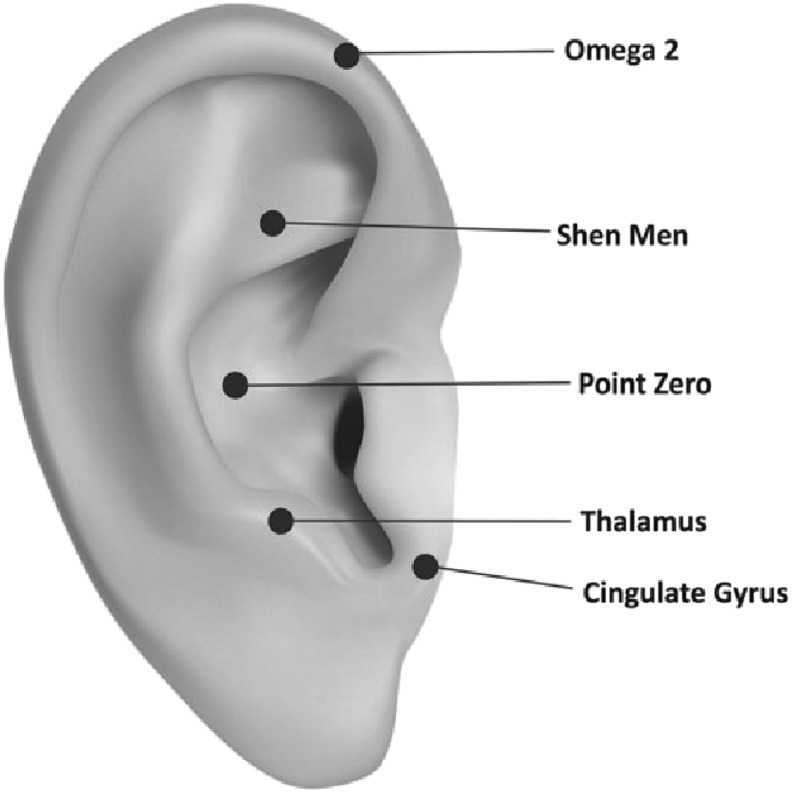

In 2001 Richard C. Niemtzow, MD, PhD, MPH, a U.S. Air Force radiation oncologist, adapted the technique of auricular acupuncture to be used as a method of rapid pain relief on the battlefield, giving rise to the term Battlefield Acupuncture (BFA).5 BFA technique uses Aiguille Semipermanente® (ASP®) needles that are placed on ear acupoints and that can remain in the ear for upward of 3–4 days.5 BFA points used for placement are thought to interfere with pain processing in the central nervous system. These areas include the thalamus, hypothalamus, cingulate gyrus, cerebral cortex, and other important structures.6

The BFA technique has been taught successfully and utilized by many physicians, especially as an emerging technique for treating pain.5 BFA is currently, to the current authors' knowledge, not taught in physical medicine and rehabilitation residency programs and is extremely limited in the formal training programs of other medical residencies in the United States.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted at a single, physical medicine and rehabilitation (PM&R) residency program with 18 PGY2–PGY4-level residents. Training consisted of a 3-hour didactic lecture from a certified BFA instructor, followed a by hands-on demonstration. The BFA instructor had been trained under Dr. Niemtzow at the Air Force Acupuncture Center. The didactic session focused on specifics of the BFA protocol, including safety, proper needle technique, patient selection, and needle care.7 During the hands-on demonstration, each participant verified his or her knowledge of the correct placement of 5 BFA needles per the BFA protocol (Fig. 1). This demonstration was first practiced with silicone ears followed by placement of needles into the other participant-residents. Gold ASP needles were used during this training.

FIG. 1.

Battlefield Acupuncture (BFA) protocol. BFA locations.

Post-training, each participant was asked to fill out a 5-point Likert scale survey in which 4 main questions were addressed:

-

(1)

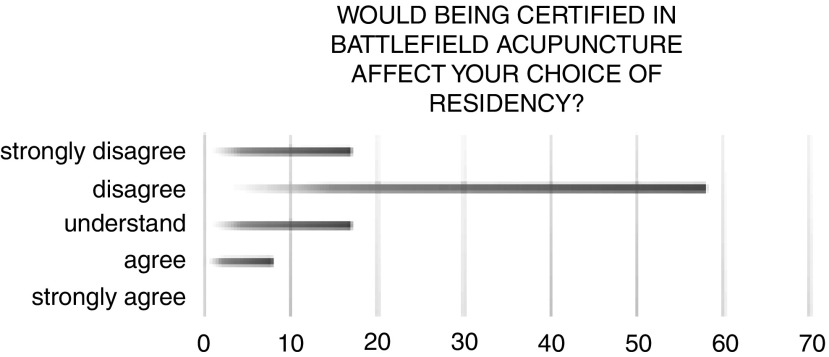

“Would being certified in Battlefield Acupuncture affect your choice of residency?” (Fig. 2)

-

(2)

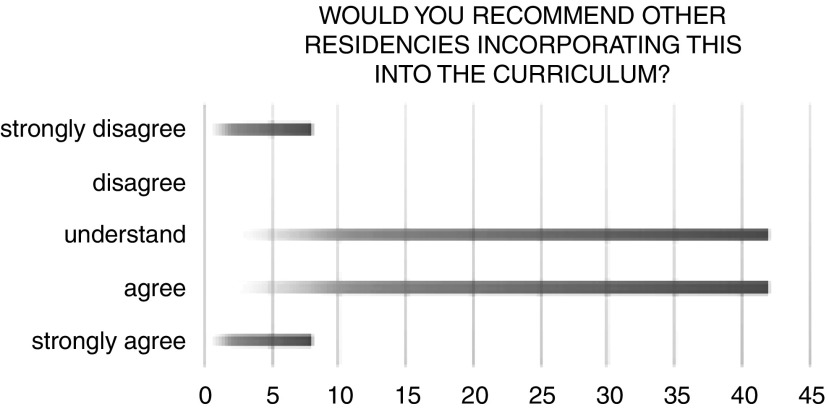

“Would you recommend other residencies incorporating this into the curriculum?” (Fig. 3)

-

(3)

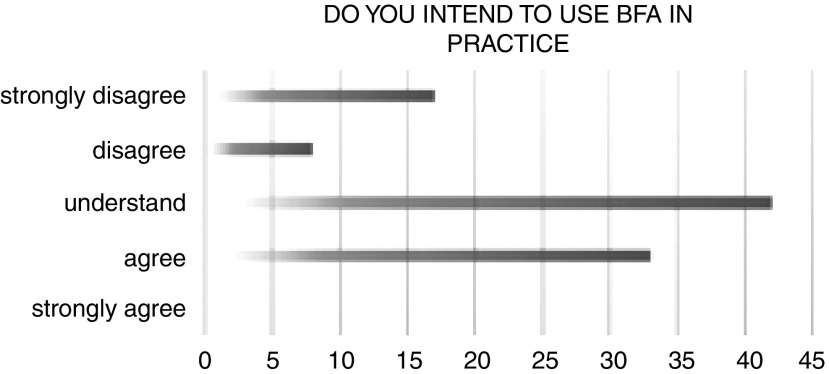

“Do you intend to use BFA in your practice?” (Fig. 4)

-

(4)

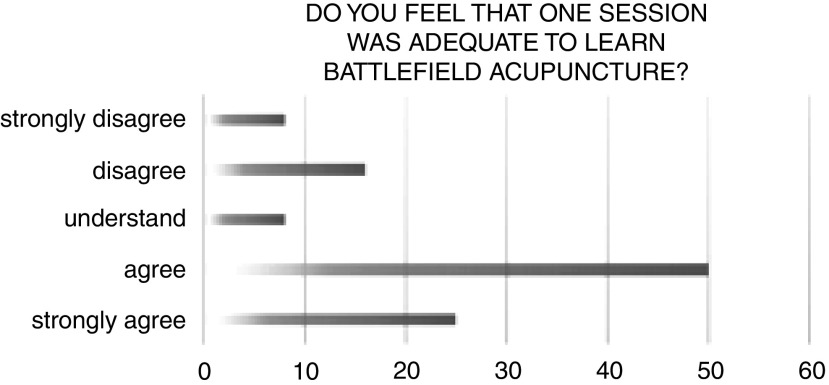

“Did you feel that one session was adequate to learn Battlefield Acupuncture?” (Fig. 5)

FIG. 2.

Choice of residency. Residents who said that being certified in Battlefield Acupuncture would affect their choices of residency.

FIG 3.

Battlefield Acupuncture (BFA) curriculum. Residents who would recommend incorporating BFA training into a residency curriculum.

FIG. 4.

Battlefield Acupuncture (BFA) in practice. Residents who intend to use BFA in their practices.

FIG. 5.

Adequate training. Residents who felt one training session was adequate to learn Battlefield Acupuncture.

Given the educational setting of this training and anonymous feedback of the participants, this survey was considered institutional review board–exempt according to criteria under common rule.

Results

After training, 12 of 18 participants responded to the survey. A majority of those who responded disagreed that their choice in a specific residency program would be affected by whether the program offered BFA certification. More participants than not recommended incorporating BFA into program curriculums. Most participants felt that a one-time didactic and training session was adequate to learn BFA.

Discussion

The use of acupuncture can be considered a fragment of the bigger picture in complementary and integrative health. Auriculotherapy by a trained practitioner can open the doorway to the use of other modes of complementary and integrative medicine (CIM) that patients might not have otherwise been exposed to. The use of CIM—specifically yoga, meditation, and chiropractic—has increased from 2012 to 2017 with most of these patients being women and people who are between the ages of 18 and 44.8

Acupuncture, in general, is considered very safe. Although rare, there have been case reports of complications. Auricular acupuncture is considered to have even far less risk of complications, given the absence of large blood vessels supplying the ear and its lack of proximity to vital organs or structures.3 However, the reality of potential complications with all kinds of acupuncture magnifies the importance of proper training.

After the National Institutes of Health Consensus Statement in 1997,9 which supported the use of acupuncture for nausea, vomiting, and post-operative pain, acupuncture has become increasingly practiced in the United States.10 Despite the demand and benefits from acupuncture in the clinical setting, its utilization and restriction varies from state to state. Some states such as Hawaii, Montana, and New Mexico require physicians to acquire licenses to practice acupuncture through the same process as those who are not physicians.10 In addition, states differ on how many acupuncture training hours are required clinically to be considered practicing within their respective scopes.

Regardless of specialty, physicians from most areas of practice are faced with the management of patients suffering from acute or chronic pain. Given auricular acupuncture's ease of use, low cost, and very low complication risk, its relevance in medicine today is clear. Implementation of BFA training in the curricula of medical residency programs, especially those with training that revolves around quality of life, pain control, and function of patients, would be most beneficial.

Some limitations to this survey most certainly exists, including that it was only one PM&R program surveyed, it had a small sample size, and a nonresponse bias. First, the high nonresponse rate to the survey could be disinterest secondary to limited hands-on exposure to BFA in a true clinical setting. This could be said as well for the more than 40% responding residents who said that they were undecided if they would use BFA in their practices (Fig. 4). Ample exposure and observation of actual patient responses to the BFA protocol after training could possibly change this indecisiveness among residents. With that said, this initial study could be expanded to survey residents' responses to BFA's usefulness and clinical utility after it has been implemented throughout training in residencies.

Conclusions

Resident-physicians training in BFA techniques is effective and well-received. Residents had favorable attitudes toward this treatment, and a minority intended to use it in their practices (Fig. 4). Further studies with larger sample sizes and follow-up of residents' inclination to use BFA in clinical settings after implementing it in residency training could prove to be a more-reliable indicator of BFA's training potential and use in a residency training program that can be incorporated in a curriculum easily on an annual or biannual basis.

Acknowledgments

The current authors would like to thank Drs. Schulman and Drake for their time and effort in instructing residents about this topic.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

References

- 1. Helms JM. Acupuncture Energetics: A Clinical Approach for Physicians. Berkeley, CA: Medical Acupuncture Publishers; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang Y, Lao L, Chen H, Ceballos R. Acupuncture use among American adults: What acupuncture practitioners can learn from National Health Interview Survey 2007? Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:710750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bonakdar RA, Sukiennik AW. Integrative Pain Management. New York: Oxford University Press; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nogier R. How Did Paul Nogier Establish the Map of the Ear? Med Acupunct. 2014;26(2):76–83 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Niemtzow RC. Battlefield Acupuncture. Med Acupunct. 2007;19(4):225–228 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Niemtzow RC, Belard J, Nogier R. Battlefield Acupuncture in the U.S. military: A pain-reduction model for NATO. Med Acupunct. 2015;27(5):344–348 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Armstrong KA, Gokal R, Durant J, Todorsky T, Chevalier A, FaShong B. Detailed Autonomic Nervous System Analysis of Microcurrent Point Stimulation Applied to Battlefield Acupuncture Protocol. Semantic Scholar; 2017. Online document at: www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Detailed-Autonomic-Nervous-System-Analysis-of-Point-Armstrong-Gokal/30ce600a6ec8eff0c800995fc738c777dab4051c Accessed February19, 2019

- 8. Clarke TC, Barnes PM, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Nahin RL. Use of Yoga, Meditation, and Chiropractors Among U.S. Adults Aged 18 and Over [NHCS Data Brief No. 325]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; November 2018. Online document at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db325-h.pdf Accessed March4, 2019 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. The National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Program: Acupuncture. Online document at: https://consensus.nih.gov/1997/1997Acupuncture107html.htm Accessed August2, 2019

- 10. Lin K, Tung C. The regulation of the practice of acupuncture by physicians in the United States. Med Acupunct. 2017;29(3):121–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]