Abstract

Objective: Needling technique is an important factor contributing to the efficacy of an acupuncture point. In previous studies, Sanyinjiao (SP 6) had an immediate analgesic effect on primary dysmenorrhea (PD) with strengthened acupuncture stimulation. Transverse needling without De Qi is accepted more easily by patients who dislike De Qi. This kind of needling also has certain effects on some conditions. This study compared the immediate analgesic effect of perpendicular De Qi needling with transverse non–De Qi needling at SP 6 in patients with PD.

Materials and Methods: Twenty-six participants with PD were randomly allocated to a perpendicular needling group (Group A; n = 13) or a transverse needling group (Group B; n = 13). Visual analogue scale (VAS; 0–100 mm) pain levels and skin-temperature measurements were determined at 4 acupuncture points before and after the interventions.

Results: Severity of dysmenorrhea was significantly decreased at 30 minutes after the interventions and at 10 minutes after needle removal in both groups (Group A: 35.77 mm and 39.62 mm less pain, respectively, on VAS; P < 0.001; Group B: 22.69 mm and 30.38 mm less pain, respectively, on VAS; P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in VAS-P [VAS for pain] scores after the interventions between the 2 groups (P > 0.05). Skin temperature at CV 4 was significantly increased after the intervention in group A only (P = 0.001).

Conclusions: Both perpendicular and transverse needling at SP 6 had an immediate analgesic effect on primary dysmenorrhea. Proper needling techniques may be applied according to the tolerance of patients.

Keywords: perpendicular needling, transverse needling, primary dysmenorrhea, SP 6, VAS, skin temperature

Introduction

Dysmenorrhea is one of the main problems during menstruation among women of reproductive age.1 The condition has two subcategories: primary and secondary dysmenorrhea. Symptoms of primary dysmenorrhea (PD) include spasmodic pain that usually occurs before, during, or after of menstruation; this pain is usually felt in the lower abdomen and occasionally radiates to the back and thighs. Dysmenorrhea causes muscle tension and vasoconstriction, reduces blood flow, and induces ischemia in target organs; this process affects skin temperature.2 Studies have shown a strong relationship between PD and uterine contractions. There is also correlation between minimal endometrial blood flow and maximal colicky pain. This phenomenon favors the idea that ischemia due to hypercontractility causes primary dysmenorrhea.3,4

There are various techniques available to treat PD. In Western Medicine (WM), therapies commonly focus on pain control by relaxing uterine muscle contractions with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or oral contraceptive pills (OCPs).5,6 However, these drugs are only effective for relieving pain temporarily and should not be taken repeatedly, as their concentrations in the blood decrease over time. NSAIDs can produce side-effects on some organs and/or the endocrine system, and also cause dependency.

In ancient Chinese acupuncture books and in modern acupuncture books and articles, studies have shown the effectiveness of acupuncture for treating dysmenorrhea.7,8 Acupuncture treatment for PD has been progressing, mostly, in the last 10 years. First, studies focused on how to select points for treatment; then compared the effects of different acupoints7–9 and compared the effectiveness of NSAIDs and OCPs with acupuncture.6,10 There were also studies on the effectiveness of acupuncture for treating patients whose conditions were resistant to conventional biomedical treatments.8 Then, studies paid attention to the complex influences of various factors on acupuncture efficacy, such as the number of needles, point locations, needling retention, intervals of acupuncture sessions, and exact times to start treatment (before/during the cycle).11–13

Moreover, body acupuncture, ear acupuncture, a combination of body and ear acupuncture,14 and body acupuncture; and tu'ina,15 herbs and moxibustion,16–18 and injections in acupoints19,20 have been compared in studies.

The term De Qi, translated as “the arrival of Qi,” which is a benchmark for acupuncture, is used widely.21 Ancient Chinese acupuncture books and most acupuncturists believe that De Qi plays an important role in the therapeutic effects of acupuncture.22,23

According to classical Chinese acupuncture theory, needling technique—particularly the depth, angle, and direction of the needling—is an essential factor that can contribute to the results of acupuncture. The anatomical structure and physiologic features of acupoints and the treatment purpose always help an acupuncturist choose the direction, angle, and depth of needle insertion at any specific point.

In body acupuncture, the current authors have used a transverse needling technique in many parts of the body (e.g., in thinly muscled areas). Transverse needling occurs when the degree of the needle's angle is <15°. There are different usages of transverse needling for treatments, such as wrist–ankle acupuncture (WAA), floating needling, dermal and intradermal needling, etc. Transverse needling, such as WAA, is widely applied to induce acupuncture analgesia with satisfactory effects.24 These techniques are characterized by needling at the superficial layer of the body, without producing—or with producing very a gentle—needling sensation. This approach has an obvious difference with standard acupuncture, which emphasizes producing the De Qi sensation. The transverse needling technique has the advantage of reducing the suffering of patients during treatment and vanquishing their fears. The technique is accepted easily by patients.

A previous study showed that perpendicular deep needling at Sanyinjiao (SP 6) with De Qi sensation had a more satisfactory immediate analgesic effect for PD, compared to the effects produced by perpendicular superficial needling without inducing De Qi.25 However, the effect of traverse superficial needling at SP 6 with the same length of needle embedded inside the point, compared to perpendicular deep needling, had not been investigated.

Therefore, this study was conducted to compare the immediate analgesic effect of perpendicular deep needling and transverse superficial needling at SP 6 in patients who have PD. Considering that menstrual pain is usually assessed by a visual analogue scale (VAS)26,27 and might relate to skin temperature,2 VAS and skin-temperature changes were measured at specific acupoints related to the Uterus to investigate the effect of different needling techniques at SP 6 on menstrual pain.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Approval

All trial procedures placed each participant's benefit as the highest priority. The present study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine (BUCM; number: 2014BZYLL0302). All study participants voluntarily provided written informed consents before randomization.

Design and Setting

A pilot prospective randomized controlled clinical trial was designed and performed at BUCM.

Participants were enrolled between March 2017 and March 2018. Participants selected from the ones who were on the campus of BUCM. On the day of the inclusion visit, informed consent was obtained from each participant.

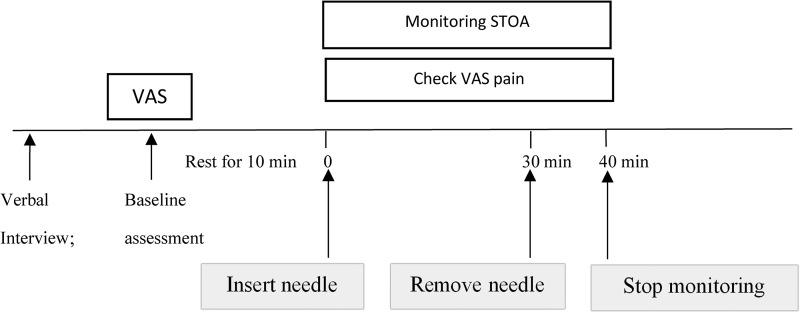

At the baseline assessment, participants completed questionnaires, including information on age, height, weight, menses, and differentiation pattern of disease. Each participant's tongue and pulse were checked and her pain was assessed with a VAS for abdominal pain. The intensity of abdominal pain was assessed before and after the needling with a 0–100 mm VAS. Skin temperature was monitored for ∼50 minutes in total, from 10 minutes before needling to 10 minutes after needle removal. The entire study design is shown in Figure 1.

FIG. 1.

Study design. STOA, skin temperature of acupoints; VAS, visual analogue scale; min, minutes.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Each participant was chosen according to the following criteria: age from 18 to 40; normal menstrual cycle (28 ± 7 days) during the last 6 months; diagnosed with PD28; diagnosed with the Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) Cold–Dampness Stagnation pattern,29; a menstrual pain score of >40 mm on the VAS; willingness to participate in the trial; no current participation in other trials; and agreement with all procedures in this trial (by signing a written informed consent form).

Participants with one or more following conditions were excluded: secondary dysmenorrhea caused by endometriosis; uterine myomas, pelvic inflammatory disease or other gynecologic problems; ages <18 or >40; irregular menstrual cycles; pregnancy and lactating; serious contraindications (e.g., life-threatening conditions or progressive central nervous disorders), and/or any other situations that the investigator judged were not suitable conditions for the study. These include uncontrolled diagnosed psychiatric disorders; histories of using antidepressants, anti-serotonin agents, barbiturates, or psychotropic drugs 2 weeks prior; and/or histories of receiving treatment for PD within the last 3 months.

Sample Size and Randomization Procedure

Among the 59 participants with PD who were invited to the study, 45 were diagnosed as having the Cold–Dampness Stagnation pattern during their visits. Nineteen patients were then excluded due to: VAS below 40 (n = 10); use of analgesic medications (n = 3); cycle irregularity (n = 3); and personal circumstances (n = 3). The final number of participants who remained in the study was 26 (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Flow chart of the study. VAS, visual analogue scale; VAS-P, VAS for pain; min, minutes.

The participants who had completed baseline evaluations were randomly classified into 2 groups at the ratio of 1:1 by random numbers generated with SPSS software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY): treatment group A “perpendicular needling with the De Qi sensation”; and treatment group B “transverse needling with a direction toward the abdomen without the De Qi sensation.”

Blinding

Participants were blinded to treatment. Only the acupuncturist was aware of the allocation. Each patient used an eye shield and, regardless of group assignment, was asked about the De Qi sensation. The assessors who recorded the results of scale assessments and skin temperature measurements were also blinded to treatment allocations.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Acupuncture interventions for both treatment groups were performed by the same acupuncturist throughout the entire study. This acupuncturist had 10 years of clinical experience in an acupuncture clinic. A supervisor monitored the performance of the protocols throughout the study. All the data collection researchers and the therapist had been trained by a supervisor—a professor with more than 20 years of clinical experience—to increase their comfort (mainly related to accuracy and conforming to standard and unified practice). These personnel were given handbooks containing detailed study protocols and standard operating procedures for the main trial.

Intervention

For each participant, the intervention was carried out when the VAS score of menstrual pain was >40 mm on the first day of menstruation and was performed only once. Prior to being needled, she was told to lie down while the acupuncturist clarified the locations of the SP 6, SP 8, SP 10, and CV 4 acupoints. Then each woman was allowed ∼10 minutes to calm her mind. Acupuncture points were determined according to the standards determined by the World Health Organization.30

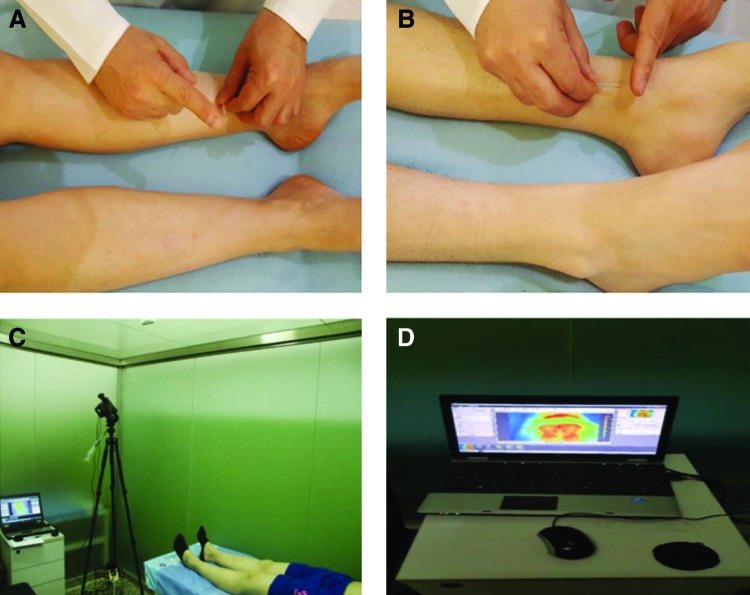

In group A, acupuncture needles were inserted perpendicularly to SP 6 bilaterally to a depth of 1–1.2 cun to induce the needling sensation with an even method (Fig.3A). Huatuo brand disposable acupuncture needles (size: 0.25 × 40 mm) were used. The needles were retained for 30 minutes. In group B, needles with the same characteristics were inserted in SP 6 transversely 1–1.2 cun toward the abdomen without inducing the De Qi sensation, and the needles were also retained for 30 minutes (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Tube needling and skin temperature monitoring. (A) Tube needling at SP 6 perpendicularly in group A. (B) Tube needling at SP 6 transversely in group B. (C) Infrared thermal camera and (D) monitoring participants. Color images are available online.

Rationale for Selection of Acupoints

The most-common causes of dysmenorrhea in TCM are Cold–Damp Stagnation and Blood Stasis in the Uterus. SP 6 is one of the most commonly used points in clinical practice for treating dysmenorrhea and conducting research on this condition.

There were several reasons to select SP 6 for this study. First, in terms of anatomy, SP 6 is controlled by the L-4–S-3 nerves, which also control the Uterus; therefore, needling SP 6 can increase the flow in the uterine artery.31 Second, SP 6 had been found to be more sensitive during dysmenorrhea.32,33 Third, SP 6 is good for treating PD caused by the Cold–Damp Stagnation pattern,34 given that, for a different pattern, a therapist should use different points7,35 according to TCM theory. Finally, SP 6 is the intersecting point of the Spleen, Liver, and Kidney channels,36 and it regulates and harmonizes Qi and Blood in the meridians to improve nourishment of Chong Mai (the Thoroughfare Vessel) and Ren Mai (the Conception Vessel) as well as the Uterus.31 Thus, SP 6 is a specific point for addressing PD.

Outcome Measures

Severity of Dysmenorrhea

The intensity of dysmenorrhea was measured with the VAS-P [VAS for pain]. The scores ranged from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 100 mm (0 = no pain and 100 = extreme pain), as participants were asked to report the severity of their pain from 0 to 100. The VAS was checked before needling (baseline measurements), 30 minutes after needling (needle removal), and 10 minutes after removing the needles.

Skin Temperature

A forward-looking infrared (FLIR) camera uses a thermographic camera that senses infrared radiation. The camera detects infrared energy (heat) and converts it into an electronic signal, which is then processed to produce a thermal image on a video monitor and perform temperature calculations. An infrared thermal camera—(FLIR SC640, FLIR system, Stockholm, Sweden; Fig.3, C and D) <F3C&D> with wide temperature ranges from −40°C to 2000°C and a thermal sensitivity of 0.1°C—was used to measure the skin temperatures. This camera had the ability to record temperature simultaneously at all 7 points. When the thermal camera captured the images, the room temperature was 27 ± 1°C with a humidity of 30% ± 5%. The camera, which was placed at a consistent distance near the participant—then recorded the skin temperatures of CV 4, SP 6, SP 8, and SP 10 at baseline without needling, 30 minutes (until needle removal), and 10 minutes after needle removal (Fig 4).

FIG. 4.

Skin temperatures of acupoints in the 2 groups. min, minutes. Color images are available online.

The process of the trial was as follows: (1) Each eligible participant was assessed for her baseline characteristics. (2) VAS values were measured on the first day of her menstrual period, when the VAS was ≥40 mm, and her skin temperatures at SP 6, SP 8, SP 10, and CV 4 were monitored with the thermal camera 10 minutes before the intervention. The temperatures just before needling were recorded. (3) SP 6 was needled perpendicularly ∼1–1.2 cun and an even method was used for ∼1 minute to induce De Qi if the participant was in group A. SP 6 was needled transversely ∼1–1.2 cun without manipulation to avoid inducing De Qi if the participant was in group B. The needles were retained for 30 minutes. During this needle retention, skin temperatures were monitored and the values were recorded, respectively, at 30 minutes after needling (needle removal) and 10 minutes after needle removal. Meanwhile, VAS values were measured, respectively, at those 2 timepoints. Figure 1 illustrates the recruitment, intervention, and measurement-taking.

Statistical Analysis

Final data analysis was performed by a separate specialist analyzer in from the Tehran University of Iran and by using SPSS software, version 23. The data were expressed as means and standard deviations. All data were analyzed based on the protocol for the subjects, given that all of the subjects completed the follow-up. A two-sample t-test (as a parametric test) or a Mann–Whitney-U test (as a nonparametric test) was performed for comparing patients' features between the 2 groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), repeated measures, was applied after parametric assumptions were established. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Of the 59 patients diagnosed with PD who were screened, 26 participants completed the study.

Baseline Characteristics

All baseline values were comparable between the 2 groups (Table 1). No significant differences (P > 0.05) between the 2 groups at baseline were found for demographic or clinical characteristics.

Table 1.

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics Between the 2 Groups (Mean ± SD)

| Characteristics | Group A (N = 13) | Group B (N = 13) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 26.62 ± 4.65 | 25.00 ± 4.42 | 0.373* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.66 ± 2.29 | 21.45 ± 2.69 | 0.830* |

| Age at menarche (years) | 12.46 ± 1.45 | 12.92 ± 1.18 | 0.383* |

| Age at disease onset (years) | 15.84 ± 3.36 | 16.53 ± 2.90 | 0.579* |

| Menstrual cycle (days) | 28.15 ± 3.13 | 28.76 ± 1.74 | 0.542* |

| Menstrual days (days) | 5.61 ± 1.71 | 5.61 ± 0.96 | 0.990* |

| Menstrual pain (VAS-P scores) | 51.54 ± 10.08 | 46.92 ± 7.51 | 0.264** |

Group A = perpendicular needling with De Qi.

Group B = transverse needling without De Qi.

P-value from between-groups comparisons using an independent sample test; **P-value from between-groups comparisons using a Mann–Whitney-U test.

SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; VAS-P, visual analogue scale for pain.

Dysmenorrhea Severity

The comparisons of VAS-P at baseline, at 30 minutes, and at 40 minutes after the intervention are given in Table 2. The severity of these patients' dysmenorrhea was decreased significantly at 30 minutes after the intervention and at 10 minutes after needle removal in both groups (Group A: 35.77 mm and 39.62 mm less pain, respectively; P < 0.001; and Group B: 22.69 mm and 30.38 mm less pain, respectively; P < 0.001). Between-group comparisons showed that there were no differences at each timepoint (at 30 minutes, P = 0. 091 and at 40 minutes, P = 0. 057).

Table 2. Comparison of VAS-P at Baseline, 30 Min and 40 Min After Intervention in Each Group, Separately and Between the 2 Groups at Each Timepoint (Mean ± SD)

| Groups | Before | 30 min | 40 min | *P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A (N = 13) | 51.54 ± 10.08 | 15.77 ± 19.67 | 11.92 ± 19.21 | < 0.001 |

| Group B (N = 13) | 46.92 ± 7.51 | 24.23 ± 12.05 | 16.54 ± 10.28 | < 0.001 |

| **P-value | 0.264 | 0.091 | 0.057 | – |

Group A = perpendicular needling with De Qi.

Group B = transverse needling without De Qi.

Bolding denotes significant results.

P-value from within-group comparisons by using repeated measures analysis of variance; **P-value from between-groups comparisons by using an independent sample test.

VAS-P, visual analogue scale for pain; min, minutes; SD, standard deviation.

Skin Temperatures

Skin Temperature at CV 4

Within-group comparison showed that skin temperature at CV4 at baseline, at 30 minutes; and at 40 minutes after the intervention were significantly increased in group A (P = 0.001), while in group B there was no significant change (P = 0.067). Between-group comparison showed that there was no significant change in temperature at CV4 (at 30 minutes; P = 0.594 and at 40 minutes, P = 0.902). See Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of Skin Temperature on CV 4 at Baseline, 30 Min and 40 Min After Intervention in Each Group, Separately and Between the 2 Groups at Each Timepoint (Mean ± SD)

| Groups | Before | 30 min | 40 min | *P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A (N = 13) | 32.75 ± 1.76 | 33.44 ± 1.59 | 33.76 ± 1.36 | 0.001 |

| Group B (N = 13) | 33.50 ± 1.39 | 33.77 ± 1.44 | 33.83 ± 1.47 | 0.067 |

| **P-value | 0.244 | 0.594 | 0.902 | – |

Group A = perpendicular needling with De Qi.

Group B = transverse needling without De Qi.

Bolding denotes a significant result.

P-values from within-group comparisons by using a repeated measures analysis of variance; **P-values from between-groups comparisons by using an independent samples test.

min, minutes; SD, standard deviation.

Skin Temperatures at 3 points on the Spleen Channel

The skin temperature changes at SP 6, SP 8, and SP 10 in both groups at 3 different timepoints are presented in Table 4 and Figure 5, respectively. In a within-group cross-sectional analysis, there were significant raises in body temperature at Left-SP 8 and at Left-and-Right–SP 10 in both groups (P < 0.05; see Table 4 and Fig. 5). However, a test of between-group effects of repeated-measures ANOVA showed that skin temperatures at SP 6, SP 8, and SP 10 in both groups were not significantly changed, neither in a time-dependent manner (P > 0.05) nor in a intervention × time interaction (P > 0.05) (see Table 5).

Table 4.

Changes of Skin Temperature on SP 6, SP 8, and SP 10 at 3 Timepoints (Mean ± SD)

| Side needled | Group | Before | 30 min | 40 min | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lt-SP 6 | Group A | 30.78 ± 1.96 | 31.35 ± 2.13 | 31.00 ± 2.04 | 0.138 |

| Group B | 30.79 ± 2.19 | 30.72 ± 0.88 | 30.86 ± 2.27 | 0.864 | |

| Rt-SP 6 | Group A | 30.67 ± 1.77 | 30.84 ± 1.82 | 30.88 ± 1.82 | 0.290 |

| Group B | 31.19 ± 1.68 | 31.29 ± 1.71 | 31.21 ± 1.64 | 0.290 | |

| Lt-SP 8 | Group A | 31.72 ± 2.14 | 32.00 ± 2.20 | 32.00 ± 2.25 | 0.025 |

| Group B | 32.13 ± 1.89 | 32.78 ± 1.83 | 32.79 ± 1.82 | < 0.001 | |

| Rt-SP 8 | Group A | 31.61 ± 2.02 | 31.80 ± 1.98 | 31.78 ± 1.93 | 0.156 |

| Group B | 32.11 ± 1.93 | 32.43 ± 1.73 | 32.44 ± 1.74 | 0.071 | |

| Lt-SP 10 | Group A | 31.30 ± 2.02 | 32.06 ± 2.28 | 32.05 ± 2.23 | 0.008 |

| Group B | 31.79 ± 2.13 | 32.40 ± 2.19 | 32.55 ± 2.19 | < 0.001 | |

| Rt-SP 10 | Group A | 31.35 ± 1.61 | 32.07 ± 1.67 | 32.14 ± 1.68 | 0.019 |

| Group B | 31.91 ± 2.15 | 32.36 ± 2.09 | 32.45 ± 2.07 | 0.012 |

Group A = perpendicular needling with De Qi.

Group B = transverse needling without De Qi.

Bolding denotes significant results.

P-values are from within-group comparisons by using repeated measures analysis of variance.

SD, standard deviation; min, minutes; Lt, left; Rt, right.

FIG. 5.

Changes of skin temperature at acupoints on the Spleen channel at three timepoints. All data are showed as mean ± standard deviation. (1) Group A–left side. (2) Group A–right side. (3) Group B–left side. (4) Group B–right side. min, minutes; LT, left; RT, right. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Table 5.

Effects of Time and Intervention on Changes of Skin Temperature at SP 6, SP 8, and SP 10

| Intervention | Time × intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Side needled | F | P-value | F | P-value |

| Lt-SP 6 | 0.031 | 0.861 | 2.274 | 0.114 |

| Rt-SP 6 | 0.403 | 0.532 | 0.791 | 0.405 |

| Lt-SP 8 | 0.693 | 0.413 | 3.112 | 0.083 |

| Rt-SP 8 | 0.693 | 0.424 | 0.349 | 0.590 |

| Lt-SP 10 | 0.275 | 0.605 | 0.394 | 0.563 |

| Rt-SP 10 | 0.277 | 0.603 | 1.179 | 0.300 |

P-values from a 2-factor measurement by analysis of variance.

F statistic from repeated measurement by 1-way analysis of variance.

Lt, left; Rt, right.

Safety of Acupuncture

No adverse effects of acupuncture were documented during the study.

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that both perpendicular deep De Qi needling and transverse superficial non–De Qi needling at SP 6 had a significant immediate effect on menstrual pain. However, there was no difference in the results produced by the two needling techniques. Perpendicular deep needling at SP 6 significantly increased the tendency toward increasing the skin temperature at CV 4. Both needling techniques significantly increased skin temperatures at SP 8 and SP 10. No significant changes in skin temperatures at the CV 4 and the 3 acupoints on the Spleen channel occurred between the two needling techniques.

Acupuncture is based on the theory of TCM that developed over years, and inducing De Qi during needling treatment is one of the main ways to produce a positive result. In modern acupuncture clinical practice, transverse superficial needling without inducing this needling sensation also produces stratified effect, particularly for patients who dislike the De Qi sensation.

The current study results showed that transverse needling without inducing De Qi produced an immediate analgesic effect that was similar to perpendicular needling that induces the De Qi sensation.

According to TCM, a person's state of health reflects the state of balance in Yin and Yang and the Qi and Blood in that person's body. One of the mechanisms of pain is obstruction of Qi and Blood in the affected body region. Pathogenic factors, such as Blood Stasis, Qi Stagnation, Phlegm, Dampness, and other conditions, can be mentioned as causative factors in the blockage. Thus, the basic therapeutic goal is removing energetic blocks that lead to Stagnation, increasing circulation and reducing localized substances, which helps reduce associated pain. The results of this study revealed that both needling techniques at SP 6 are good for relieving menstrual pain by dredging the channels.

In terms of modern biomedicine, increasing the intensity of stimulation of acupuncture might contribute to better effects by activating more neural and neuroactive components of the body.37 Generally, increasing the intensity of acupuncture stimulation can be achieved by using stronger manipulation; or by increasing the depth of needling, size of the needles, and number of needles, etc. However, a previous study showed that deep needling at SP 6 had produced a better result than superficial needling.25 In the present study, the needle was inserted transversely with the same length of the needle embedded inside each acupoint as deep needling, instead of superficial perpendicular needling, showing that the stimulation area of the two techniques is similar. Therefore, these findings suggest that, in order to take the advantage of the lower needling sensation induced by superficial needling and improve the effect simultaneously, transverse needling might be a good choice by increasing the stimulation area.

In the current study, changes in skin temperature before and after the intervention were monitored by using thermal-camera technology to provide objective evidence of the microcirculation and movement of energy induced by needling.

During menstruation, as endometrial cells are destroyed, prostaglandins and other inflammatory mediators in the uterus will be decreased. This can induce rhythmic hypercontractility in uterine muscle with vasoconstriction and finally result in uterine ischemia that causes the changes in skin temperatures.38

Acupuncture stimulation has increased blood flow in local tissue in animals39 and humans.40 Acupuncture effects influence neural, endocrinologic, cardiovascular, and immunologic functions. One of the cardiovascular effects acupuncture stimulation elicits is enhanced muscle-blood flow via peripheral vasodilatation. Increased blood flow after acupuncture can be attributable to the C-fiber–mediated axon reflex41 that results from noxious mechanical stimulation. Noninvasive methodologies, such as laser Doppler flowmetry and thermography, could primarily be used to measure and evaluate a superficial skin blood-flow response. In vivo near-infrared spectroscopy is a noninvasive technology for measuring muscle-blood volume and oxygenation responses,42 a technique that is suitable for assessing the effect of acupuncture on the blood flow of deep-tissue and metabolic responses.

Increased temperature, in turn, improves circulation, oxygen supply, and cell metabolism, reducing the level of inflammatory or toxic substances.

The present study investigated the influence of needling techniques on the PD-ameliorating effect of SP 6. The results support those of other studies on the effectiveness of using SP 6 to alleviate dysmenorrhea38,43,44 and also confirm the relationship between SP 6 and the pattern of PD.34 Based on the theory of classical acupuncture, dysmenorrhea could be mainly attributed to Spleen, Thoroughfare, and Conception Vessel disorders. Skin temperatures on the abdomen and its related acupoints in women with dysmenorrhea have been reported to be lower than in women without menstrual pain.39,40,45

The SP 6 factor was its being an intersecting point of the Liver, Kidney, and Spleen channels; thus, it is a specific point for PD. SP 8 is the Xi-cleft point and is used for diagnosis and treating Blood disorders and acute pain. SP 10 is a Sea of Blood and is used to regulate menstruation. Conception Vessels are closely related to the Uterus and CV 4 crosses the point of Conception Vessel with the Spleen, Liver, and Kidney channels. This point is in the lower abdomen and is used for addressing irregular menstruation. In the perpendicular De Qi needling group, skin temperature was significantly increased at CV 4 after needling, suggesting the relationship between deep perpendicular needling and its target organ. However, in transverse non–De Qi needling at SP 6, raising the skin temperature in the Spleen channel was more significant than the CV 4 effect. These phenomena could suggest different mechanisms and pathways according to theory of channels and layers for relieving pain. Further studies with larger sample sizes should be carried out.

Strengths and Limitations

This study was the first pilot randomized trial comparing the effects of different needling techniques at SP 6 for relieving pain caused by dysmenorrhea. As an exploratory trial, certain limitations have to be considered. The sample size of this study was small, because this was a pilot study, so the small sample size might have lowered the statistical power of the study.

Improving the validity and reliability of this research and evaluating different types of needling and their mechanisms requires the following: (1) increasing sample size and (2) using more laboratory and imaging procedures.

Conclusions

This study showed that, both perpendicular and transverse needling at SP 6 had an immediate analgesic effect on pain caused by PD. Proper needling techniques may be applied according to the tolerance of patients. Here is a recommendation to acupuncturists: If patients dislike the strong needling sensation, a transverse non-De Qi needling method can be used.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the participants in this trial.

Funding was provided by the Research Development Foundation of the BUCM (2018-ZXFZJJ-010 and 2016-ZXFZJJ-086).

Author Disclosure Statement

No financial conflicts exist.

References

- 1. Yang J, Chen J, Lao L, et al. Effectiveness study of moxibustion on pain relief in primary dysmenorrhea: Study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:434978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Park MK, Watanuki S. Specific physiological responses in women with severe primary dysmenorrhea during the menstrual cycle. J Physiol Anthropol Appl Hum Sci. 2005;24(6):601–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yu YP, Ma LX, Ma YX, et al. Immediate effect of acupuncture at Sanyinjiao (SP6) and Xuanzhong (GB39) on uterine arterial blood flow in primary dysmenorrhea. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(10):1073–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Altunyurt S, Göl M, Sezer O, Demir N. Primary dysmenorrhea and uterine blood flow: A color Doppler study. J Reprod Med. 2005;50(4):251–255 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iorno V, Burani R, Bianchini B, Minelli E, Martinelli F, Ciatto S. Acupuncture treatment of dysmenorrhea resistant to conventional medical treatment. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2008;5(2):227–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sriprasert I, Suerungruang S, Athilarp P, Matanasarawoot A, Teekachunhatean S. Efficacy of acupuncture versus combined oral contraceptive pill in treatment of moderate-to-severe dysmenorrhea: A randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:735690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sun J, Wang Y, Zhang Z, et al. Efficacy of filiform needle manipulation on primary dysmenorrhea: A systematic review [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2017;37(8):887–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu YQ, She YF, Zhu J, et al. Discussion about TCM causes and pathogenesis of moderate and severe PD based on questionnaire investigation among female college students [in Chinese]. Zhong Hua Zhong Yi Yao Za Zhi. 2012;27(1):54–56 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Armour M, Smith CA. Treating primary dysmenorrhoea with acupuncture: A narrative review of the relationship between acupuncture “dose” and menstrual pain outcomes. Acupunct Med. 2016;34(6):416–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pouresmail Z, Ibrahimzadeh R. Effects of acupressure and ibuprofen on the severity of primary dysmenorrhea. J Tradit Chin Med. 2002;22(3):205–210 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ru S, Zhang P, Li J, et al. Clinical trials for observing the influence of acupuncture needle-stimulation induced sharp pain on curative effect in primary dysmenorrhea patients [in Chinese]. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 2016;41(2):154–158 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bu YQ. Observation on therapeutic effect of acupuncture at Shiqizhui (Extra) for primary dysmenorrhea at different time [sic; in Chinese]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2011;31(2):110–112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang S, Lu D, Li Y. Observation on therapeutic effect of acupoint application on dysmenorrhea of Excess syndrome and effect on prostaglandins [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2009;29(4):265–268 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Asher GN, Jonas DE, Coeytaux RR, Reilly AC, Loh YL, Motsinger-Reif AA, Winham SJ. Auriculotherapy for pain management: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(10):1097–1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lin LL, Liu CZ, Huang BY. Clinical observation on treatment of primary dysmenorrhea with acupuncture and massage [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2008;28(5):418–420 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang S, Li X, Zhang L, Xu Y, Li Q. Clinical observation on medicine-separated moxibustion for treatment of primary dysmenorrhea and study on the mechanism [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2005;25(11):773–775 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hsu CS, Yang JK, Yang LL. Effect of “Dang-Qui-Shao-Yao-San” a Chinese medicinal prescription for dysmenorrhea on uterus contractility in vitro. Phytomedicine. 2006;13(1–2):94–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yang M, Chen X, Bo L, et al. Moxibustion for pain relief in patients with primary dysmenorrhea: A randomized controlled trial. PloS One. 2017;12(2):e0170952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huang QM, Liu L. Wet needling of myofascial trigger points in abdominal muscles for treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea. Acupunct Med. 2014;32(4):346–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang L, Cardini F, Zhao W, Regalia AL, Wade C, Forcella E, Yu J. Vitamin K acupuncture point injection for severe primary dysmenorrhea: An international pilot study. MedGenMed. 2004;6(4):45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhao JS. A Glossary of Basic Concepts and Terms in Acupuncture [in Chinese]. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ren YL, Guo TP, Du HB, et al. A survey of the practice and perspectives of Chinese acupuncturists on Deqi. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:684708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yuan HW, Ma LX, Zhang P, et al. An exploratory survey of Deqi sensation from the views and experiences of Chinese patients and acupuncturists. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:430851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang HB, Zhao S, Li X, Ma SX, Li QI, Cui JM. Efficacy observation on wrist–ankle needle for primary dysmenorrhea in undergraduates [in Chinese]. Zhong Guo Zhen Jiu. 2013;33(11):996–999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhao MY, Zhang P, Li J, et al. Influence of De Qi on the immediate analgesic effect of SP6 acupuncture in patients with primary dysmenorrhoea and Cold and Dampness Stagnation: A multicenter randomised controlled trial. Acupunct Med. 2017;35(5):332–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gallagher EJ, Bijur PE, Latimer C, Silver W. Reliability and validity of a visual analog scale for acute abdominal pain in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20(4):287–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bijur PE, Silver W MA, Gallagher EJ. Reliability of the visual analog scale for measurement of acute pain. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(12):1153–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lefebvre G, Pinsonneault O, Antao V, et al. ; Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. Primary dysmenorrhea consensus guideline [in English and French]. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2005;27(12):1117–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. The Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China. Consensus Guideline About Trial for Primary Dysmenorrhea with New Chinese Herbs, 1st ed. Beijing: The Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China; 1993:263–266 [Google Scholar]

- 30. World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for the Western Pacific. WHO Standard Acupuncture Point Locations in the Western Pacific Region. Manila: WHO; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ma YX, Ma LX, Liu XL, et al. A comparative study on the immediate effects of electroacupuncture at Sanyinjiao (SP6), Xuanzhong (GB39) and a non-meridian point, on menstrual pain and uterine arterial blood flow, in primary dysmenorrhea patients. Pain Med. 2010;11(10):1564–1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang C, Huang X, Luo Y, Jing J, Wan L, Wang L. Reflection of dysmenorrhea in acupoint Sanyinjiao (SP 6) region [in Chinese]. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 2014;39(5):401–405 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. She YF, Ma LX, Qi CH, et al. Do changes in electrical skin resistance of acupuncture points reflect menstrual pain? A comparative study in healthy volunteers and primary dysmenorrhea patients. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:836026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu YQ, Ma LX, Xing JM, et al. Does Traditional Chinese Medicine pattern affect acupoint specific effect? Analysis of data from a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial for primary dysmenorrhea. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19(1):43–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yu S, Yang J, Yang M, et al. Application of acupoints and meridians for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea: A data mining–based literature study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:752194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maciocia G. Spleen Channel. In: The Foundations of Chinese Medicine; A Comprehensive Text, 3rd ed. Edinburgh, UK: Elsevier; 2015:995–1006 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang ZJ, Wang XM, McAlonan GM. Neural acupuncture unit: A new concept for interpreting effects and mechanisms of acupuncture [review article]. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:429412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhan C. Treatment of 32 cases of dysmenorrhea by puncturing Heguand Sanyinjiao acupoints. J Tradit Chin Med. 1990;10(1):33–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yuan HW, Ma LX, Qi DD, Zhang P, Li CH, Zhu J. The historical development of Deqi concept [sic] from classics of Traditional Chinese Medicine to modern research: Exploitation of the connotation of Deqi in Chinese medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:639302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jun EM, Chang S, Kang DH. Effects of acupressure on dysmenorrhea and skin temperature changes in college students: A non-randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(6):973–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nishijo K, Mori H, Yosikawa K, Yazawa K. Decreased heart rate by acupuncture stimulation in humans via facilitation of cardiac vagal activity and suppression of cardiac sympathetic nerve. Neurosci Lett. 1997;227(3):165–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hamaoka T, McCully KK, Quaresima V. Near infrared spectroscopy/imaging for monitoring muscle oxygenation and oxidative metabolism in healthy and diseased humans. J Biomed Optics. 2007;12(6):062105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen MN, Chien LW, Liu CF. Acupuncture or acupressure at the Sanyinjiao (SP6) acupoint for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea: A meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:493038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Smith CA, Crowther CA, Petrucco O, Beilby J, Dent H. Acupuncture to treat primary dysmenorrhea in women: A randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:612464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yang JM, Shen XY, Zhang L, et al. The effect of acupuncture to SP6 on skin temperature changes of SP6 and SP10: An observation of “Deqi.” Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:595963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]