Abstract

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) is responsible for non-shivering thermogenesis and is an attractive therapeutic target for combating obesity and related diseases. Human BAT activity has been evaluated by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18FDG-PET/CT) under acute cold exposure, but the method has some serious limitations, including radiation exposure. Infrared thermography (IRT) may be a simple and less-invasive alternative to evaluate BAT activity. In the present study, to establish an optimal condition for IRT, using a thermal imaging camera, skin temperature was measured in the supraclavicular region close to BAT depots (Tscv) and the control chest region (Tc) in 24 young healthy volunteers. Their BAT activity was assessed as the maximal standardized uptake value (SUVmax) by 18FDG-PET/CT. Under a warm condition at 24–27°C, no significant correlation was found between the IRT parameters (Tscv, Tc,, and the difference between Tscv and Tc,, Δtemp) and SUVmax, but 30–120 min after cold exposure at 19°C, Tscv and Δtemp were significantly correlated with SUVmax (r = 0.40–0.48 and r = 0.68–0.76). Δtemp after cold exposure was not affected by mean body temperature, body fatness, and skin blood flow. A lower correlation (r = 0.43) of Δtemp with SUVmax was also obtained when the participant’s hands were immersed in water at 18°C for 5 min. Receiver operating characteristic analysis revealed that Δtemp after 30–60 min cold exposure can be used as an index for BAT evaluation with 74% sensitivity, 92% specificity, and 79% diagnostic accuracy. Thus, IRT may be useful as a simple and less-invasive method for evaluating BAT, particularly for large-scale screening and longitudinal repeat studies.

Introduction

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) is responsible for non-shivering thermogenesis (NST) and is therefore involved in the regulation of whole-body energy expenditure and body fatness [1]. In humans, the current gold standard method to assess BAT is 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–positron emission tomography (PET) in combination with computed tomography (CT) and cold exposure, which uses cold-activated glucose uptake as an index of BAT activity [2]. However, this 18FDG-PET/CT method has some serious drawbacks such as radiation exposure, the need for cold exposure, and the high cost of the device, which have limited its frequent use in both experimental and clinical studies. Although several alternative methods to overcome these limitations have been developed, including magnetic resonance imaging [3], near-infrared time-resolved spectroscopy [4], and contrast-enhanced ultrasound [5], they are also relatively expensive and not yet soundly confirmed for their validity and reliability [6].

There have been reports to assess the thermogenic activity of BAT by monitoring the temperature of the skin (Tsk) overlying BAT depots. A few studies using a wire-less thermistor probe revealed that cold-induced changes in Tsk of the supraclavicular region (Tscv) close to BAT depots positively correlated with the activity and volume of BAT estimated by 18FDG-PET/CT [7,8]. Infrared thermography (IRT) can also be used to evaluate Tsk with visualization by measuring the infrared radiation emitted from the body surface. Jang et al. showed by IRT that differences between Tsk in a control chest region and Tscv (Δtemp) were greater in subjects having higher BAT activities after a 2-h cold exposure [9]. Furthermore, a significant relationship between the IRT method and 18FDG-PET/CT also has been confirmed [9,10]. However, during the cold exposure experiments of these studies, Tsk was measured before and after a 2-h cold exposure protocol, where the subjects with light-clothing were kept in a room at 19°C (cold exposure) or on mattresses perfused with cooled water at ~17°C; these protocols may not induce muscle shivering, but are apparently uncomfortable, stressful, and intolerable for most individuals, particularly those with cardiovascular diseases. Therefore, less invasive and easier protocols are needed for frequent assessment of BAT, in both experimental and clinical studies.

Symonds et al. [11] and Ang et al. [12] tested the feasibility of IRT as a non-invasive method by monitoring the changes in Tscv 5 min after placing the hand and/or feet of the participant in water at 20°C. This hand immersion protocol is apparently much less invasive and is easily applicable in various experimental and clinical settings; however, they did not validate the correlation of their data with the BAT activity assessed by 18FDG-PET/CT. In the present study, to establish optimal conditions for IRT assessment of human BAT, we monitored the response of Tsk to cold exposure for 10–120 min, in healthy subjects with a wide range of BAT activity. We also examined Tsk response after 5-min hand immersion in the same subjects, and compared the two protocols. Our results revealed that Δtemp, only after 30-min exposure to cold at 19°C, correlated well with the BAT activity assessed by 18FDG-PET/CT, indicating that this protocol can be used for BAT evaluation with an accuracy of approximately 80%.

Methods

Twenty-four healthy male volunteers (age: 23.5 ± 3.6 years; body mass index [BMI]: 21.6 ± 2.5 kg/m2) participated in this study in winter from December 2017 to March 2018. This study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (Fortaleza 2013). The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of Kyoto Medical Center (no. 15–092) and was registered at the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) center (UMIN000029206). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

18FDG-PET/CT

After overnight fasting for ~12 h, subjects were exposed to cold by being kept in an air-conditioned room at 19°C with standardized light clothing (a patient gown), with intermittent placement of their feet on an ice block wrapped in cloth for ~4 min at 5-min intervals to avoid cooling-associated pain [13]. After 1 h under these cold conditions, each subject was intravenously injected with 18F-FDG (1.66–5.18 mega [106] Becquerel (MBq)/kg body weight) and kept under the same cold conditions. At 1 h after the 18F-FDG injection, 18FDG-PET/CT scans were obtained with a PET/CT system (Aquiduo; Toshiba Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan). BAT activity in both the right and left supraclavicular regions was quantified based on the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax), defined as the radioactivity per ml within the region of interest divided by the injected dose in mBq/g body weight. BAT was defined as tissue with Hounsfield units −300 to −10 on CT with an SUV ≥ 1.5. PET and CT images were co-registered and analyzed using VOXBASE workstation (J-MAC System, Sapporo, Japan).

IRT

IRT was carried out using a thermal imaging camera (DE-TC1000T; D-eyes Inc., Osaka, Japan) fastened to a tripod. The thermal resolution was 160 × 120. The Tscv of both the right and left sides was measured from each image. The Tsk of the chest region (Tc) immediately lateral to the sternum approximating the second intercostal space, which is apart from the underlying BAT depots, was simultaneously measured as a control [13]. The subjects fasted for ~12 h, wore a light patient gown (about 0.2 clo), and underwent IRT successively for the following two tests: 5-min hand immersion into 18°C water and 120-min cold exposure at 19°C, as described below. IRT images were analyzed using a modified (D-eyes Inc.) version of ThermalCam v.1.1.0.9 software (Laon People Inc., Seoul, Korea).

Cold exposure test

Cold exposure was performed using two adjacently located rooms controlled at 27°C and 19°C, respectively, with 40% relative humidity. The coefficient of variance (CV) was 2.5% in the 27°C room and 1.1% in the 19°C room. Subjects were seated in an upright position looking straight ahead for ~30 min in the 27°C room and underwent IRT and other measurements including skin blood flow (SkBF), then moved to the 19°C room and underwent IRT at 10–30 min intervals for 120 min.

Hand immersion test

For the hand immersion test, the ambient room temperature and water temperature were 24°C and 18°C, respectively, with 40% relative humidity. The water temperature in a tank was maintained using a thermostatic water circulator (LV-200; Toyo Roshi Kaisha, Tokyo, Japan), and the CV of water temperature was 5.4%. After more than 30 min of rest, the subjects immersed both hands into the water tank for 5 min [11,12].

Anthropometric parameters and others

BMI was calculated as body weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters, and body fat mass was estimated by the multifrequency bioelectric impedance method (Karada Scan HBF-701; Omron, Kyoto, Japan). Visceral and subcutaneous fat areas at the abdominal level of L4–L5 were estimated from the CT images. Total abdominal fat area was calculated as the sum of visceral and subcutaneous fat areas.

Tympanic and sublingual temperature was measured using an earphone type infrared tympanic thermometer (CET-101; Nipro, Osaka, Japan) and an electronic thermometer before and after 2-h cold exposure (MC-172L; Omron Healthcare Co., Kyoto, Japan), respectively. A small disc-type temperature data logger (Thermochron SL; KN Laboratories, Osaka, Japan) was used to monitor Tsk on the forehead, left upper chest, non-dominant ventral forearm, non-dominant ventral middle finger, left shin, and left instep as reported previously [8]. The mean Tsk was calculated according to a modified Hardy and DuBois’s equation [14].

SkBF in the supraclavicular region and back (left scapula) was measured using a laser tissue blood flowmeter (FLO-N1; Omegawave, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Data were sampled using an A/D converter and recorded at 1-s intervals using a personal computer. In the subsequent analysis, artifacts observed in the raw data were eliminated using a 10-s median filter [15]. Before and after 2-h cold exposure, subjects were asked to rate shivering according to a modified version of a previously used scale [16] consisting of four levels: 1 = no shivering, 2 = slight shivering, 3 = moderate shivering, and 4 = heavy shivering. Cold sensation [17] and discomfort [18] were also assessed before and after 2-h cold exposure.

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Two-way analysis of variance with repeated measures was used to test interactions (group × time) and main effects (group, time). If there was a significant interaction or main effect, time or group differences in variables between baseline and after the test, were analyzed with the paired and unpaired t tests, respectively. The relationship between the data of IRT and 18FDG-PET/CT was analyzed by Pearson’s correlation analysis, where SUVmax was log-transformed because of the non-normal distribution determined with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Values were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to evaluate the area under the ROC curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, and the accuracy of IRT parameters. Then the AUC of after cold exposure was compared to that of 27°C. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v.19 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and Easy R software (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan) [19].

Results

18FDG-PET/CT revealed that 5 of 24 subjects showed undetectably low BAT activity (SUVmax < 1.5), and thus, were defined as BAT-negative, whereas the remaining 19 subjects showed a detectable activity (SUVmax = 1.8~26.8), and thus, were defined as BAT-positive. There was no significant difference in the anthropometric parameters between the two subject groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of study subjects.

| Measurement | All | BAT-positive | BAT-negative | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 24 | 19 | 5 | - |

| Age, years | 23.5 ± 3.6 | 23.8 ± 3.8 | 22.4 ± 2.2 | 0.44 |

| Height, cm | 172.1 ± 4.6 | 172.6 ± 5.0 | 170.2 ± 1.7 | 0.53 |

| Weight, kg | 64.0 ± 8.6 | 65.4 ± 8.9 | 58.9 ± 5.6 | 0.24 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21.6 ± 2.5 | 21.9 ± 2.6 | 20.3 ± 1.9 | 0.29 |

| Body fat, % | 16.6 ± 4.4 | 17.4 ± 4.4 | 13.7 ± 3.4 | 0.22 |

| Skeletal muscle, kg | 35.6 ± 1.8 | 35.3 ± 1.8 | 36.6 ± 1.5 | 0.29 |

| Visceral fat area, cm2 | 42.8 ± 31.6 | 45.0 ± 33.9 | 34.6 ± 21.3 | 0.47 |

| Subcutaneous fat area, cm2 | 88.7 ± 54.4 | 94.3 ± 56.4 | 67.4 ± 44.9 | 0.34 |

| Total abdominal fat area, cm2 | 131.5 ± 72.7 | 139.3 ± 74.5 | 102.0 ± 63.5 | 0.31 |

| SUVmax | 7.0 ± 6.9 | 8.1 ± 6.1 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | < 0.01 |

Values represent mean ± standard deviation. BAT, brown adipose tissue; BMI, body mass index; SUVmax, maximal standardized uptake value.

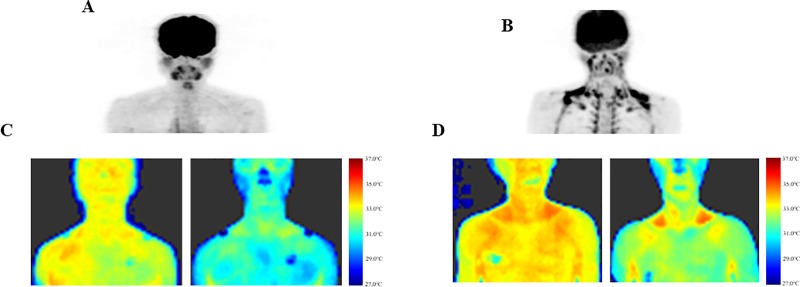

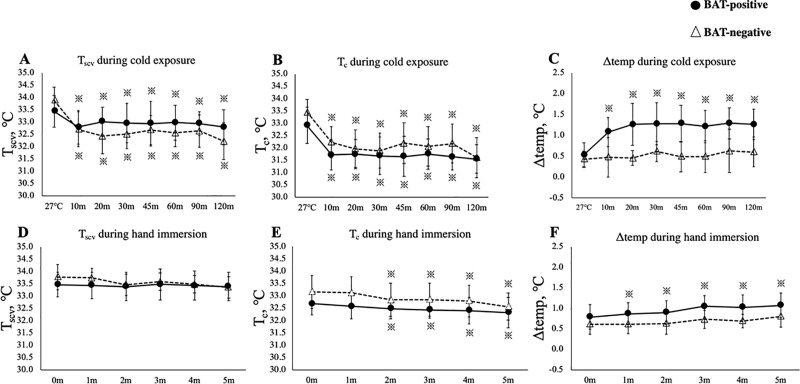

Fig 1 shows typical images of IRT and 18FDG-PET/CT at 27°C and 2 h after cold exposure. Tsk was considerably different between the two subjects, both under warm (27°C) and cold (19°C) conditions. Despite the individual differences, as summarized in Fig 2A and 2B, under the warm condition at 27°C, Tscv was insignificantly higher than Tc in both BAT-negative and positive groups. After cold exposure, Tscv and Tc seemed slightly higher and lower, respectively, in the BAT-positive group. Although neither Tc nor Tscv was significantly different between the two groups at any time point during the 2-h cold exposure, the cold-induced drop in Tscv was significantly smaller (P < 0.05) in the BAT-positive group (0.7 ± 0.6°C) than in the BAT-negative group (1.7 ± 1.1°C), while the drop in Tc was comparable in the two groups (1.4 ± 0.7°C vs. 1.8 ± 1.0°C; P = 0.16).

Fig 1. Typical images of 18FDG-PET/CT and IRT.

Typical images of 18FDG-PET/CT in BAT-negative (A) and positive subjects (B). Typical images of IRT method in BAT-negative (C) and positive subjects (D) before (left) and after 2-h cold exposure (right).

Fig 2. Skin temperature changes after cold exposure and hand immersion.

Tscv, skin temperature of the supraclavicular region; Tc, skin temperature of the chest region; Δtemp, differences between Tscv and Tc. Tscv (A), Tc (B), and Δtemp (C) during cold exposure. Tscv (D), Tc (E), and Δtemp (F) during hand immersion. * vs 27°C or 0 m.

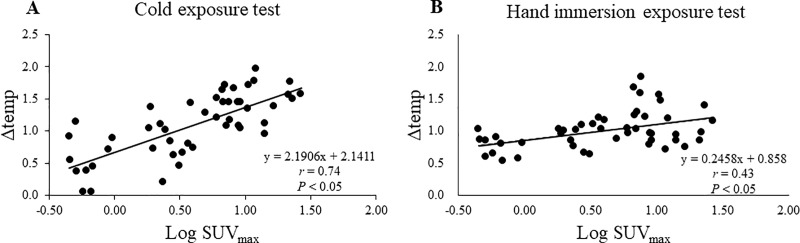

To confirm the effect specific to the supraclavicular region, the difference between Tscv and Tc was calculated and expressed as Δtemp. As shown in Fig 2C, Δtemp in the BAT-positive group was 0.5 ± 0.3°C at 27°C, rose remarkably and significantly 10 min after cold exposure, reached a steady level of 1.3 ± 0.5°C at 30 min, and was maintained at high levels of 1.2~1.3°C thereafter. In contrast, Δtemp in the BAT-negative group showed no significant change after cold exposure, being 0.5~0.6°C, which was significantly lower (P < 0.05) than that of the BAT-positive group. Thus, cold-induced change in Δtemp was observed only in the BAT-positive group. As the supraclavicular region, but not the control chest region, is close to the underlying BAT depots, Δtemp after cold exposure is likely to reflect the thermogenic activity of BAT and would serve as a BAT-specific index. Consistent with this idea, a fairly positive correlation (r = 0.74) was observed between the Δtemp at 2-h cold exposure and the BAT activity expressed as log SUVmax (Fig 3). Significant correlations with SUVmax were also found in Tscv itself and the cold-induced Tscv change (Tscv-time), but with lower correlation coefficients (r = 0.48 and r = 0.59, Table 2). In contrast, neither Tscv nor Δtemp at 27°C correlated with SUVmax. Comparative positive correlations between IRT parameters and log SUVmax were also observed even at 30 min after cold exposure, including those for Tscv (r = 0.40), Δtemp (r = 0.68) and Tscv-time (r = 0.57).

Fig 3.

Relationship between log SUVmax and Δtemp in the cold exposure test (A) and the hand immersion test (B). Δtemp, difference between skin temperature on the supraclavicular region (Tscv) and that on the chest region (Tc); SUVmax, maximal standardized uptake value. The correlation coefficient in the cold exposure test (r = 0.74) was significantly higher than that in the hand immersion test (r = 0.42) (P < 0.05). Data were obtained from both the right and left sides in 24 subjects.

Table 2. Correlation coefficients between IRT parameters and SUVmax in the cold exposure test.

| 27°C | 19°C (30 min) | 19°C (120 min) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tscv | -0.24 | 0.40* | 0.48* |

| Tc | -0.25 | 0.08 | -0.002 |

| Δtemp | 0.16 | 0.68* | 0.74* |

| Tscv-time | - | 0.57* | 0.59* |

| Tc-time | - | -0.14 | 0.22 |

SUV, standardized uptake value; Tscv, skin temperature on the supraclavicular region; Tc, skin temperature on the chest region; Δtemp, differences between Tscv and Tc; Tscv-time, difference in Tscv between 19°C and 27°C; Tc-time, difference in Tc between 19°C and 27°C.

*P < 0.05 (Pearson’s correlation analysis).

We also examined the effects of 2 h-cold exposure on tympanic and sublingual temperatures and skin temperature in various regions including the forehead, forearm, hand, finger, calf, and foot. Similar to the supraclavicular and chest regions, skin temperature in these regions dropped, showing the mean Tsk from 33.1°C ± 0.4°C to 29.7°C ± 0.3°C (P < 0.01), but no notable difference was found between the BAT-positive and -negative groups (data not shown). The effects of cold-exposure on SkBF were also examined. After 2 h-cold exposure, SkBF decreased by 15.6% (P < 0.05) in the back, whereas it did not change in the supraclavicular region (P = 0.51), and no difference was found between the BAT-positive and -negative groups. We also investigated the relationship between possible confounding factors and Tsk (Table 3). The % body fat was negatively correlated with Tscv and Tc at 27°C. The mean Tsk was positively correlated with Tscv and Tc at 27°C and Tscv at 19°C. The SkBf was positively correlated with Tc at 27°C and Tscv and Tc at 19°C. However, Δtemp did not correlate with any of the parameters or temperatures (Table 3). There was no perceived shivering either before (0.3 ± 0.5) or after (-0.3 ± 0.5) cold exposure, while cold sensation was -2.1 ± 1.0 (-2 = cool) and discomfort was −1.0 ± 0.8 (−1 = uncomfortable) at the end of cold exposure.

Table 3. The correlation coefficient between Δtemp and possible confounding factors.

| 27°C | 19°C 30 min | 19°C 120 min | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Body fat | Tscv | -0.38* | -0.24 | -0.09 |

| Tc | -0.39* | -0.35* | -0.26 | |

| Δtemp | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.20 | |

| Mean Tsk | Tscv | 0.31* | 0.37* | 0.40* |

| Tc | 0.36* | 0.39* | 0.39* | |

| Δtemp | -0.21 | -0.02 | 0.10 | |

| SkBf | Tscv | 0.07 | - | 0.56* |

| Tc | 0.34* | - | 0.36* | |

| Δtemp | -0.12 | - | 0.22 |

Tsk, skin temperature; skBf, skin blood flow; Tscv, Tsk on the supraclavicular region; Tc, Tsk on the chest region; Tscv, differences between Tscv and Tc; Δtemp, changes in Tscv; ΔTc, changes in Tc. The body fat was used as baseline data. The mean Tsk was calculated according to a modified Hardy and DuBois’s equation. The skBf was evaluated in the supraclavicular and control regions at 27°C and 19°C.

*P < 0.05 (Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation analysis).

We also examined the effects of hand immersion in water for the same subjects participating in the above-described cold exposure test. As shown in Fig 2D and 2E, during 5-min hand immersion, Tc significantly decreased (P < 0.05), while Tscv did not change. The calculated Δtemp was increased after the 5-min hand immersion only in the BAT-positive group (P < 0.05). A significant positive correlation between Δtemp and log SUVmax was found, but the correlation coefficient (r = 0.43) was lower than that after cold exposure (Fig 3, Table 4).

Table 4. Correlation coefficients between IRT parameters and SUVmax in the hand immersion test.

| Before | After (5 min) | |

|---|---|---|

| Tscv | -0.01 | 0.14 |

| Tc | -0.12 | -0.11 |

| Δtemp | 0.27 | 0.43* |

| Tscv-time | - | 0.17 |

| Tc-time | - | 0.04 |

SUV, standardized uptake value; Tscv, skin temperature on the supraclavicular region; Tc, skin temperature on the chest region; Δtemp, differences between Tscv and Tc; Tscv-time, difference in Tscv between before and after hand immersion; Tc-time, difference in Tc between before and after hand immersion.

*P < 0.05 (Pearson’s correlation analysis).

The ROC analysis between Δtemp and log SUVmax revealed that AUCs were 0.80 and 0.85 after 30-min and 120-min cold exposure, respectively, but 0.59 at 27°C and 0.77 after 5-min hand immersion. As summarized in Table 5, the cut-off value of Δtemp and accuracy seemed to reach plateau levels 30 min after cold exposure. When the cut-off value for detecting BAT-positive subject was set as 1.01°C for Δtemp after 30-min cold exposure, the sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy were 74.3%, 92.3%, and 79.2%, respectively, which were comparable with those after 120-min cold exposure.

Table 5. Accuracy for brown adipose tissue activity during cold exposure.

| Cut-off value,°C |

Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Accuracy, % | AUC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27°C | 0.78 | 28.6 | 100 | 47.9 | 0.59 |

| 19°C 30 min | 1.01 | 74.3 | 92.3 | 79.2 | 0.80* |

| 19°C 60 min | 1.03 | 85.7 | 84.6 | 85.4 | 0.89* |

| 19°C 120 min | 0.96 | 80.0 | 76.9 | 79.2 | 0.85* |

*P < 0.05, vs. 27°C

Discussion

In this study, to investigate the optimal index for assessing BAT thermogenic activity using the IRT method, healthy volunteer subjects were exposed to the cold for 2 h, and the skin temperature of the supraclavicular region close to BAT depots (Tscv) was compared with the metabolic activity (SUVmax) assessed by the standard 18FDG-PET/CT method. Our results showed that the cold-induced response of Δtemp, reflecting the difference between Tscv and a control chest region apart from BAT depots (Tc), was the most relevant index of SUVmax.

Human BAT is mainly present in the supraclavicular region, which has been the focus of most studies measuring the temperature response by the IRT method or using wire-less thermistors. In a previous thermistor study, a correlation coefficient of r = 0.52 was found between Tscv after cold exposure and SUVmax [7], which is similar to our result (r = 0.48). However, the Tsk value itself may be affected by various factors such as the subcutaneous fat thickness [20,21], SkBF, and possibly other thermogenic tissues. Therefore, to minimize the influence of these factors, we calculated Δtemp as the difference between Tscv and Tc, and found a higher correlation coefficient (r = 0.74). In fact, Tscv and Tc correlated with body fatness (% body fat), mean body temperature, and SkBf, while Δtemp showed no significant correlation with these parameters.

Previous reports have shown that BAT activity could be evaluated by the IRT method using thermoneutral conditioning [9,21] or the 5-min hand immersion test [11,12]. These methods are simple and less invasive, and thus would be useful in clinical settings. However, these methods have not been validated in relation to the BAT activity assessed by 18FDG-PET/CT. In our study, under a thermoneutral condition without cold exposure, no correlation of Tscv and Δtemp with SUVmax was found. In the hand immersion test, however, Δtemp correlated with SUVmax, but with a lower correlation coefficient (0.43) than found in the cold exposure test (r = 0.74). Thus, the hand immersion test may be feasible only for subjects with relatively high BAT activity.

In most previous human studies, BAT was assessed after 2 h or longer cold exposure, regardless of the 18FDG-PET/CT or IRT method [1, 9]. In this study, we monitored Tsk responses to cold exposure at 10~30-min intervals for 120 min, finding that the response in Δtemp reached a steady level after 30 min and was maintained thereafter. In fact, comparative positive correlations between the IRT parameters and SUVmax were observed even at 30 min after cold exposure, including that for Δtemp (r = 0.68). Accordingly, the ROC analysis for the data after 30-min cold exposure revealed that the sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy were similar after a 120-min cold exposure. Thus, 120-min cold exposure, as applied in the previous studies, is not necessary. Our easier protocol of 30-min cold exposure is sufficient for BAT evaluation by the IRT method.

One of the limitations of this study is that all our participants were young and non-obese males. To confirm the overall feasibility of our IRT method, it should also be tested in other groups, particularly in female and/or obese individuals. They have more subcutaneous fat which is insulating, and may influence Δtemp depending on the mass/thickness of the fat. Moreover, Δtemp may not only be influenced by heat directly transmitted from underlying BAT, but also from blood flow in the carotid and subclavian arteries. Further studies are needed to examine the possible confounding effects of these factors.

In conclusion, Δtemp calculated from IRT after 30-min cold exposure highly correlated with SUVmax assessed by 18FDG-PET/CT. Thus, the IRT method may be useful as a simple and less-invasive alternative for evaluating BAT, particularly for large-scale screening and longitudinal repeat studies.

Supporting information

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the volunteers who participated in this study.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (17J11622, 26291099, 18K11013) and Kao Research Council for the study of Healthcare Science. D-eyes provided support in the form of salaries for authors TH, but did not have any additional role in the study design, data curation and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The specific roles of these authors are articulated in the ‘author contributions’ section.

References

- 1.Kajimura S, Saito M. A new era in brown adipose tissue biology: molecular control of brown fat development and energy homeostasis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2014;76:225–249. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen KY, Cypess AM, Laughlin MR, Haft CR, Hu HH, Bredella MA, et al. Brown adipose reporting criteria in imaging studies (BARCIST 1.0): Recommendations for standardized FDG-PET/CT experiments in humans. Cell Metab, 2016;24:210–222. 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu HH, Wu TW, Yin L, Kim MS, Chia JM, Perkins TG, et al. MRI detection of brown adipose tissue with low fat content in newborns with hypothermia. Magn Reson Imaging. 2014; 32:107–117. 10.1016/j.mri.2013.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nirengi S, Homma T, Inoue N, Sato H, Yoneshiro T, Matsushita M, et al. Assessment of human brown adipose tissue density during daily ingestion of thermogenic capsinoids using near-infrared time-resolved spectroscopy. J Biomed Opt. 2016;21:91305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flynn A, Li Q, Panagia M, Abdelbaky A, MacNabb M, Samir A, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound: A novel noninvasive, nonionizing method for the detection of brown adipose tissue in humans. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1247–1254. 10.1016/j.echo.2015.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chondronikola M, Beeman SC, Wahl RL. Non-invasive methods for the assessment of brown adipose tissue in humans. J Physiol. 2018;596:363–378. 10.1113/JP274255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boon MR, Bakker LE, van der Linden RA, Pereira Arias-Bouda L, Smit F, Verberne HJ, et al. Supraclavicular skin temperature as a measure of 18F-FDG uptake by BAT in human subjects. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98822 10.1371/journal.pone.0098822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anouk AJJ, van der Lans AA, Vosselman MJ, Hanssen MJ, Brans B, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD. Supraclavicular skin temperature and BAT activity in lean healthy adults. J Physiol Sci. 2016;66:77–83. 10.1007/s12576-015-0398-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang C, Jalapu S, Thuzar M, Law PW, Jeavons S, Barclay JL, et al. Infrared thermography in the detection of brown adipose tissue in humans. Physiol Rep. 2014;2:e12167 10.14814/phy2.12167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Law J, Morris DE, Izzi-Engbeaya C, Salem V, Coello C, Robinson L, et al. Thermal imaging is a noninvasive alternative to PET/CT for measurement of brown adipose tissue activity in humans. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:516–522. 10.2967/jnumed.117.190546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Symonds ME, Henderson K, Elvidge L, Bosman C, Sharkey D, Perkins AC, et al. Thermal imaging to assess age-related changes of skin temperature within the supraclavicular region co-locating with brown adipose tissue in healthy children. J Pediatr. 2012;161:892–898. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.04.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ang QY, Goh HJ, Cao Y, Li Y, Chan SP, Swain JL, et al. A new method of infrared thermography for quantification of brown adipose tissue activation in healthy adults (TACTICAL): A randomized trial. J Physiol Sci. 2017;67:395–406. 10.1007/s12576-016-0472-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saito M, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Matsushita M, Watanabe K, Yoneshiro T, Nio-Kobayashi J, et al. High incidence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue in healthy adult humans: Effects of cold exposure and adiposity. Diabetes. 2009;58:1526–1531. 10.2337/db09-0530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardy JD, Dubois EF. The technique of measuring radiation and convection. J Nutr. 1938; 15:461–475. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wakabayashi H, Wijayanto T, Kuroki H, Lee JY, Tochihara Y. The effect of repeated mild cold water immersions on the adaptation of the vasomotor responses. Int J Biometeorol. 2012;56:631–637. 10.1007/s00484-011-0462-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nielsen R, Endrusick TL. Sensations of temperature and humidity during alternative work/rest and the influence of underwear knit structure. Ergonomics. 1990;33:221–234. 10.1080/00140139008927112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gagge AP, Stolwijk JA, Hardy JD. Comfort and thermal sensations and associated physiological responses at various ambient temperatures. Environ Res. 1967;1:1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu Z, Li N, Cui H, Peng J, Chen H, Liu P. Using upper extremity skin temperatures to assess thermal comfort in office buildings in Changsha, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:E1092 10.3390/ijerph14101092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanda K. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software 'EZR' for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:452–458. 10.1038/bmt.2012.244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarasniemi JT, Koskensalo K, Raiko J, Nuutila P, Saunavaara J, Parkkola R, et al. Skin temperature may not yield human brown adipose tissue activity in diverse populations. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2018:e13095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gatidis S, Schmidt H, Pfannenberg CA, Nikolaou K, Schick F, Schwenzer NF. Is it possible to detect activated brown adipose tissue in humans using single-time-point infrared thermography under thermoneutral conditions? impact of BMI and subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151152 10.1371/journal.pone.0151152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.