Abstract

Objective:

To determine if transfusing ABO compatible platelets has a greater effect on incremental change in platelet count as compared to ABO incompatible platelets in critically ill children.

Design:

Secondary analysis of a prospective, observational study. Transfusions were classified as either ABO compatible, major incompatibility or minor incompatibility. The primary outcome was the incremental change in platelet count. Transfusion reactions were analyzed as a secondary outcome.

Setting:

Eighty two pediatric intensive care units in 16 countries.

Patients:

Children (3 days to 16 years of age) were enrolled if they received a platelet transfusion during one of the predefined screening weeks.

Interventions:

None

Measurements and Main Results:

Five hundred and three children were enrolled and had complete ABO information for both donor and recipient, as well as laboratory data. 342 (68%) received ABO-identical platelets, 133 (26%) received platelets with major incompatibility, and 28 (6%) received platelets with minor incompatibility. Age, weight, proportion with mechanical ventilation or underlying oncologic diagnosis did not differ between the groups. After adjustment for transfusion dose, there was no difference in the incremental change in platelet count between the groups; the median (IQR) change for ABO-identical transfusions was 28 (8–68) x109 cells/L, for transfusions with major incompatibility 26 (7–74) x109 cells/L, and for transfusions with minor incompatibility 54 (14–81) x109 cells/L (p = 0.37). No differences in count increment between the groups were noted for bleeding (p=0.92) and non-bleeding patients (p=0.29). There were also no differences observed between the groups for any transfusion reaction (p=0.07).

Conclusions:

No differences were seen in the incremental change in platelet count nor in transfusion reactions when comparing major ABO incompatible platelet transfusions with ABO compatible transfusions in a large study of critically ill children. Studies in larger, prospectively enrolled cohorts should be performed to validate whether ABO matching for platelet transfusions in critically ill children is necessary.

Keywords: platelet transfusion, ABO compatibility, critical illness, pediatrics

INTRODUCTION

Platelet transfusions are frequently prescribed for critically ill children who are either bleeding (therapeutic transfusions) or at risk of bleeding (prophylactic transfusions). A recent large, international, observational study of both therapeutic and prophylactic transfusions in critically ill children demonstrated a high mortality rate (25%) for all children receiving a platelet transfusion for any indication, as well as an independent association between total platelet dose and mortality.1 In children receiving platelet transfusions, each additional dose 10 mL/kg of platelets received was associated with a 2% increase in mortality, after accounting for severity of illness represented by organ dysfunction scoring on the day of transfusion, bleeding and the use of extracorporeal life support. Any modifiable determinants of platelet transfusions should therefore be explored given the potential morbidity and mortality that may be associated with this therapy.

Providing ABO-identical platelet transfusions is not always considered necessary. The requirement for matching ABO blood group for platelets are not as stringent as those for RBC transfusions. Platelets express ABO blood group antigens2 and correspondingly the plasma found in platelet products may contain antibodies against A or B antigens, depending upon the ABO type of the donor, that may be reactive with the recipient’s antigens.3 The practice of ABO matching of platelet transfusions in blood banks is variable with no consensus guidelines; approximately 20% of hospitals have no institutional written guidelines on this topic.4 The proportion of critically ill children receiving ABO compatible platelet transfusions has not been reported. The transfusion of ABO incompatible platelets may have the benefit of effectively increasing the availability of platelet product options, which is considered a limited resource, especially in emergencies such as life-threatening hemorrhage. Increased availability also reduces waste of platelet products, given their short storage duration (5–7 days). However, ABO mismatching has been implicated in acute hemolysis5, increased fever and alloimmunization6, and reduced efficacy of platelet transfusions.7

Few studies have demonstrated the effects of ABO incompatibility in pediatric platelet transfusions8 and no previous studies have reported the results in critically ill children. Therefore, as the primary objective of this study, we sought to describe the efficacy of ABO compatibility on the incremental change in platelet count following platelet transfusions in critically ill pediatric patients. As a secondary objective, we evaluated associations between the receipt of ABO incompatible platelet transfusions and the occurrence of transfusion reactions. Lastly, we evaluated patient variables associated with the receipt of compatible versus incompatible platelet transfusions.

METHODS

This study, approved by the Institutional Review Board at Weill Cornell Medicine, is an a priori secondary analysis of a prospective, observational study examining the epidemiology of platelet transfusions in critically ill children (“Point Prevalence Study of Platelet Transfusions in Critically Ill Children,” otherwise known as P3T).1 Eighty-two sites from sixteen countries contributed data. Each site was assigned six random weeks (between September 2016 to April 2017) during which they screened subjects for eligibility and enrollment. A child was enrolled if he/she was between the ages of 3 days and 16 years of age and received a platelet transfusion prescribed by the intensive care medical team during one of the screening days. Patients were excluded if life expectancy was considered to be less than 24 hours, gestational age of the patient was less than 37 weeks at the time of admission, or the patient had already been enrolled in a previous screening week. In addition, they were excluded from this analysis if they received multiple pooled platelet units with different ABO compatibility or if they received several platelet transfusions in the interval between laboratory assessments. In total, 16,934 patients were screened and 559 eligible patients receiving platelet transfusions were enrolled. Data for the P3T study were recorded in the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) web data application and extracted for this secondary analysis. Data regarding ABO compatibility was collected around the platelet transfusion at time of enrollment but did not include all data from every platelet transfusion received during the subject’s PICU stay.

Data collected included patient demographics, reason for admission, any prior platelet transfusions during the current ICU admission, validated measures of organ dysfunction (PELOD-2 scoring)9, information regarding the platelet product (including the ABO type of the donor and recipient), and any adverse reactions that occurred during the transfusion. The adverse reactions documented included fever of ≥ 38.5C (or increase in temperature by 1 degree Celsius from baseline in a patient who was already febrile), hypotension, bronchospasm, urticaria, and hemolytic reactions. The total platelet count before and after the platelet transfusion was recorded if obtained as standard of care. The timing of the assays was determined by the medical team. The pre-transfusion platelet count was assayed within 36 hours of start of the transfusion and recorded according to the following time intervals: < 1 hour, 1–2 hours, 2–6 hours, 6–12 hours, 12–24 hours and 24–36 hours. The timing of the post-transfusion platelet count was recorded in relation to the completion of the transfusion of interest with the same time intervals as listed above.

ABO major incompatibility was defined as platelets from A, B or AB donors to O recipients, or from AB donors to A or B recipients. Transfusions with bidirectional incompatibility (A donor to B recipient or B donor to A recipient) were included in the major incompatibility group. Minor incompatibility was defined as platelets from O donors to A, B or AB recipients, or from A or B donors to AB recipients.

Demographic and clinical characteristics were described as counts and percentages or median and interquartile range (IQR) as appropriate. Categorical variables were compared using either Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test, depending on the size of the sample. Continuous variables were compared using Kruskal Wallis test. Two-sided p values below 0.05 were considered significant and there was no adjustment made for multiple comparisons. If the Kruskal Wallis test showed a statistical difference between groups, then one to one comparison was performed to determine which groups were significantly different. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Of the 559 subjects enrolled in P3T, five hundred and three (90%) had data on ABO compatibility and pre and post-transfusion platelet counts recorded. Of these, 342/503 (68%) were classified as ABO compatible, 133/503 (26%) had major incompatibility and 28/503 (6%) had minor incompatibility. Seven transfusions had bi-directional incompatibility and were classified along with the major incompatibility group.

The transfusions occurred across diverse locations: 351/503 (70%) in North America, 81/503 (16%) in Europe, 35/503 (7%) in Oceania, 21/503 (4%) in Asia, and 15/503 (3%) in the Middle East. There was variability in the percentage of compatible transfusions given in each region: 66% in North America, 70% in Europe, 71% in Oceania, 91% in Asia, and 67% in the Middle East (p< 0.001).

The demographics and clinical characteristics are described in Table 1. The groups were comparable across various characteristics except for median PELOD-2 scoring being slightly higher in the ABO minor incompatibility group as compared to ABO-identical transfusions or major incompatibility groups (p=0.04). For patients weighing less than 15kg, 161 (67%) received ABO compatible transfusions, 65 (27%) received transfusions with major incompatibility and 15 (6%) received transfusions with minor incompatibility. The admitting diagnoses of the subjects and the therapies they received are summarized in Table 2. There were no differences in admitting diagnoses (apart from those with septic shock and those with cardiac insufficiency not related to cardiac surgery), medications with antiplatelet effects, use of extracorporeal therapies, or median dose of platelet transfusions prior to enrollment in the study between the three groups. Patients received a median (IQR) platelet dose of 30 (13–86) mL/kg during their PICU admission prior to enrollment in the study. The total median (IQR) number of platelet transfusions received during their entire admission was 4 (2–11).

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Patients

| Patient Variable | Compatible (n = 342) |

Major Incompatibility ( n = 133) |

Minor Incompatibility (n = 28) |

p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr), median (IQR) | 4.5 (0.7–11.1) | 3.1 (0.4–10.3) | 3.1 (0.2–10.7) | 0.38 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 183 (54) | 85 (64) | 13 (46) | 0.07 |

| Weight (kg), median (IQR) | 16.8 (7.2–35.6) | 15.7 (5.4–32.2) | 13.0 (4.1–41.5) | 0.37 |

| Days since admission, median (IQR) | 3 (0–7) | 2 (0–7) | 2 (1–6) | 0.93 |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 224 (66) | 84 (63) | 22 (79) | 0.28 |

| Underlying oncologic diagnosis, n (%) | 148 (43) | 56 (42) | 12 (43) | 0.97 |

| PELOD-2 Score prior to transfusion, median (IQR) | 7 (4–9) | 7 (5–9) | 9 (6–10) | 0.04 |

| ABO blood type of recipient | ||||

| O | 155 (43) | 93 (70) | 0 (0) | |

| A | 127 (37) | 16 (12) | 14 (50) | |

| B | 43 (13) | 24 (18) | 6 (21) | |

| AB | 17 (5) | 0 (0) | 8 (29) | |

p-values comparing medians using Kruskal Wallis test and categorical variables using Chi-square test

Table 2.

Admitting Diagnoses and Therapies Received

| Admitting Diagnoses | Compatible (n = 342) |

Major Incompatibility ( n = 133) |

Minor Incompatibility (n = 28) |

p-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reason for PICU Admission, n (%): | ||||

| Organ Failure | ||||

| Respiratory insufficiency/failure | 141 (41) | 53 (40) | 10 (36) | 0.83 |

| Renal failure | 32 (9) | 16 (12) | 1 (4) | 0.36 |

| Hepatic failure | 18 (5) | 7 (5) | 1 (4) | 0.93 |

| Shock | ||||

| Septic shock | 88 (26) | 18 (14) | 7 (25) | 0.02 |

| Hemorrhagic shock | 21 (6) | 7 (5) | 1 (4) | 0.82 |

| Other shock | 15 (4) | 6 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.52 |

| Trauma | 8 (2) | 5 (4) | 0 (0) | 0.46 |

| Cardiac | ||||

| Cardiac surgery-bypass | 39 (11) | 18 (14) | 3 (11) | 0.80 |

| Cardiac surgery-no bypass | 6 (2) | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.50 |

| Cardiac – non-surgical | 27 (8) | 16 (12) | 6 (21) | 0.04 |

| Post-operative | ||||

| Emergency surgery | 14 (4) | 7 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.45 |

| Elective surgery | 14 (4) | 10 (8) | 0 (0) | 0.14 |

| Post-op liver transplant | 10 (3) | 2 (2) | 1 (4) | 0.64 |

| Neurosurgical | ||||

| Traumatic brain injury | 5 (2) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.65 |

| Intracranial bleed/intracranial hypertension | 9 (3) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.68 |

| Neurologic | ||||

| Seizure | 9 (3) | 2 (2) | 2 (7) | 0.23 |

| Encephalopathy | 29 (9) | 8 (6) | 2 (7) | 0.66 |

| Meningitis | 4 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.72 |

| Veno-occlusive disease | 4 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.80 |

| New leukemia/hyperleukocytosis | 14 (4) | 2 (2) | 2 (7) | 0.23 |

| Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis | 5 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.68 |

| Other | 25 (7) | 6 (5) | 4 (14) | 0.16 |

| Therapies Received, n (%) | ||||

| Medications | ||||

| Milrinone | 55 (16) | 26 (20) | 4 (14) | 0.62 |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories | 5 (2) | 5 (4) | 0 (0) | 0.20 |

| Aspirin | 9 (3) | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.66 |

| Devices | ||||

| Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation | 60 (18) | 18 (14) | 7 (25) | 0.29 |

| Continuous renal replacement therapy | 31 (9) | 18 (14) | 3 (11) | 0.36 |

| Intermittent hemodialysis | 3 (1) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.54 |

| Molecular adsorbent circulating system | 2 (0.6) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.26 |

| Median (IQR) dose (mL/kg) platelet transfusions received prior to enrollment | 30 (12–77) | 58 (22–108) | 19 (11–29) | 0.06 |

p-values calculated using Chi-squared for large samples and Fisher’s Exact for small samples

Table 3 describes the receipt of the three ABO compatibility for bleeding versus non-bleeding indications. The indication for the platelet transfusions (treatment of bleeding versus prophylaxis) differed between the three ABO compatibility groups (p=0.04). Thirty-two percent (110/342) of the ABO compatible transfusions were given to bleeding patients. Forty-two percent (56/133) of the transfusions with major incompatibility were given to bleeding patients and twenty-one percent (6/28) of the transfusions with minor incompatibility were given to bleeding patients. Table 4 illustrates the attributes of the platelet products transfused.

Table 3.

Distribution of ABO compatibility groups for bleeding versus non-bleeding indications

| Indication | Compatible (342) |

Major Incompatibility (133) |

Minor Incompatibility (28) |

p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bleeding | 110 (32) | 56 (42) | 6 (21) | 0.04 |

| Non-bleeding (prophylaxis) | 232 (68) | 77 (58) | 22 (79) | 0.04 |

p-values calculated variables using Chi-square test (or Fisher’s Exact for small samples).

Table 4.

Attributes of Platelet Products Transfused

| Transfusion Variable | Compatible (342) |

Major Incompatibility (133) |

Minor Incompatibility (28) |

p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apheresed platelets | 288 (84) | 128 (96) | 27 (96) | 0.001 |

| Whole blood derived platelets | 54 (16) | 5 (4) | 1 (4) | 0.001 |

| Leukoreduction | 320 (94) | 128 (96) | 27 (100) | 0.61 |

| Irradiation | 267 (78) | 111 (84) | 22 (79) | 0.39 |

| HLA-matched | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.87 |

| Volume reduced (washed) | 23 (7) | 11 (8) | 4 (15) | 0.19 |

| Pathogen inactivated | 16 (5) | 5 (4) | 2 (7) | 0.20 |

| Storage duration | 4 (3–5) | 5 (4–5) | 5 (4–5) | 0.10 |

All variables reported as n (%) except for storage duration which is reported as median (IQR). p-values comparing medians using Kruskal Wallis test and categorical variables using Chi-square test (or Fisher’s Exact for small samples). There was missing data on leukoreduction in 3 cases, irradiation in 6 cases, HLA matching in 17 cases, volume reduction in 46 cases, pathogen inactivation in 38 cases, and storage duration in 44 cases. For all analyses, complete-case analysis approach was applied.

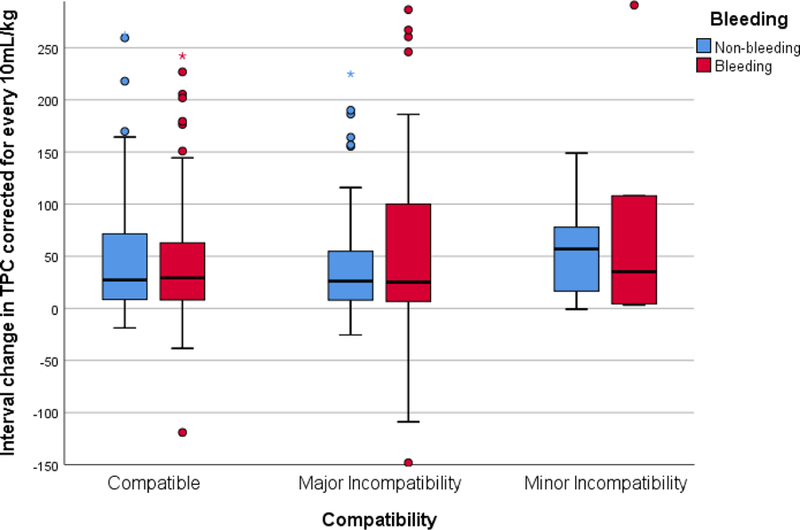

The breakdown of time intervals between the pre-transfusion platelet count and the start of the transfusion of interest are as follows (data was available for 501 transfusions): 36/501 (7%) within < 1 hour, 102/501 (20%) within 1–2 hours, 223/501 (44%) within 2–6 hours, 105/501 (21%) within 6–12 hours, 29/501 (6%) within 12–24 hours and 6/501 (<2%) within 24–36 hours. The breakdown of time intervals between the end of the transfusion of interest and the post-transfusion platelet count are as follows (data on timing is available in all of the transfusions): 43/503 (9%) within < 1 hour, 81/503 (16%) within 1–2 hours, 171/503 (34%) within 2–6 hours, 124/503 (25%) within 6–12 hours, 67/503 (13%) within 12–24 hours and 17/503 (<4%) within 24–36 hours. There was a wide variation in the interval changes in platelet count, corrected for a standard dose of 10 mL/kg, with the majority of interval changes occurring between −40 to +150 ×109 cells/L. For all transfusions, there was a median (IQR) interval rise of 28 (8–70) x109 cells/L for every 10 mL/kg transfused. Figure 1 shows the interval change for each ABO compatibility group. These results were consistent when bleeding and non-bleeding patients were analyzed separately. In bleeding patients, the median (IQR) interval rise was 29 (8–64) x109 cells/L for every 10 mL/kg transfused for ABO compatible transfusions, 23 (7–105) x109 cells/L for transfusions with major incompatibility, and 35 (4–108) x109 cells/L for transfusions with minor incompatibility (p=0.93). Similarly, for non-bleeding patients, the median (IQR) interval rise was 27 (8–70) x109 cells/L for every 10 mL/kg transfused for ABO compatible transfusions, 26 (8–55) x109 cells/L for transfusions with major incompatibility, and 57 (17–78) x109 cells/L for transfusions with minor incompatibility (p=0.29). Figure 2 demonstrates the interval changes in total platelet count in bleeding versus non-bleeding subjects by ABO compatibility group.

Figure 1.

Interval change in Total Platelet Count for each compatibility group

Figure 2.

Interval change in Total Platelet Count in bleeding versus non-bleeding subjects for each compatibility group

Given the possibility that the presence of extracorporeal support may bias the results since it is known to affect the incremental change in platelet count due to adherence or destruction, a subgroup analysis was performed excluding those patients on ECLS. The results were consistent. The median (IQR) interval rise was 28 (8–65) x109 cells/L for every 10 mL/kg transfused for ABO compatible transfusions, 22 (7–74) x109 cells/L for transfusions with major incompatibility, and 37 (4–78) x109 cells/L for transfusions with minor incompatibility (p=0.74).

Similarly, given the fact that subjects with an underlying oncologic diagnosis would have likely been exposed to more platelet transfusions and therefore have a less robust response in the incremental change in platelet count, we performed a subgroup analysis of the 295 subjects who did not have an underlying oncologic diagnosis. The results remained consistent. The median (IQR) interval rise was 36 (10–79) x109 cells/L for every 10 mL/kg transfused for ABO compatible transfusions, 34 (8–90) x109 cells/L for transfusions with major incompatibility, and 57 (37–81) x109 cells/L for transfusions with minor incompatibility (p=0.39).

Given the possibility of differences in those multiply transfused, a sub-group analysis was performed in the 92 subjects who had received ≥ 30 mL/kg of platelet transfusions during their admission, prior to enrollment in the study. In this group, 61/92 (66%) received ABO compatible transfusions, 27/92 (29%) received transfusions with major incompatibility, and 4/92 (5%) received transfusions with minor incompatibility. The median (IQR) interval rise in platelet count for every 10 mL/kg of platelets transfused for each group was as follows: 25 (9–68) x109 cells/L for ABO compatible transfusions, 28 (6–51) x109 cells/L for transfusions with major incompatibility and 61 (46–80) x109 cells/L for transfusions with minor incompatibility. There were no statistically significance differences between these median values (p=0.11).

Data on transfusion reactions were available in 493 subjects. Table 5 depicts the incidence of transfusion reactions. There was no significant difference in any transfusion reaction between the groups (p=0.07) or in any individual adverse event. There were no hemolytic reactions or septic reactions documented during any of the transfusions.

Table 5.

Transfusion Reactions

| Reactions | Compatible (332) | Incompatible (161) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any transfusion reaction n (%) | 25 (7) | 5 (3) | 0.07 |

| New fever | 9 (3) | 2 (1) | 0.36 |

| Increase in temp by 1C if already febrile | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 0.66 |

| Urticaria | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 0.99 |

| Bronchospasm | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0.99 |

| Hypotension | 12 (4) | 1 (0.6) | 0.07 |

| Transfusion stopped | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 0.99 |

All variables reported as n (%). There were no hemolytic reactions reported for any of the transfusions. p-values calculated using Chi-squared for large samples and Fisher’s Exact for small samples.

DISCUSSION

This study reports the count increment of platelet transfusions as it relates to ABO compatibility in the largest cohort of critically ill children published to date. It is the first study to report on the proportion of ABO compatible versus incompatible platelet transfusion received and the regional variability in practice. More than two-thirds of children received ABO-identical platelet transfusions. Though there were minor differences between the ABO compatibility groups regarding admitting diagnosis, the population represents a diverse cohort both in geography and pathophysiology. No patient characteristics were associated with the receipt of an ABO compatible platelet transfusion. No differences were seen in the incremental differences in platelet count following transfusion, between the compatibility groups. Likewise, no differences were seen in documented transfusion reactions, in any of the groups.

Our results should be interpreted in the context of ongoing uncertainty and controversy regarding reduced efficacy following the transfusion of ABO incompatible platelets. 10,11 Several adult studies have reported a benefit to providing ABO compatible platelet transfusions. Increased post-transfusion platelet count increments have been reported in platelet survival studies in both healthy subjects12 and adult hematology patients13–15 for those who received ABO compatible as compared to platelet transfusions with major incompatibility. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that the differential increments in platelet count post transfusion are most pronounced in patients who have received multiple doses of platelets (generally defined as > 3 separate transfusions).16 One hypothesis relates this to the development of high titer isoagglutinins, antibodies to human leukocyte antigens (HLA) or antibodies to human platelet antigens (HPA).17 One study of six platelet refractory patients reported that these patients who received ABO incompatible platelets have circulating immune complexes of ABO antigens and their corresponding antibodies for at least several days.18 Circulating ABO immune complexes have been shown to affect platelet function, red cell integrity and hemostasis in vitro.19 Unfortunately, there was no control group in this study to determine if ABO immune complexes also occur in patients who do not have platelet refractoriness. No studies have been reported in critically ill adults.

In comparison to these studies in adults, we did not detect significant differences in post-transfusion platelet count increments when comparing ABO compatible platelet transfusions to those with major or minor compatibility in critically ill children. There are very limited published reports on the efficacy of ABO compatibility for platelet transfusions in children. One study on this topic was published by Julmy and colleagues in 2009 and focused on fifty children with hematologic malignancies, solid tumors or aplastic anemia who were receiving platelet transfusions (primarily for prophylactic indications) and who were prospectively enrolled.19 The primary comparison was the post-transfusion platelet count (measured one hour after completion of the transfusion) between ABO-identical and major-mismatched groups. After comparing the laboratory results of 400 transfusions, the authors reported significantly worse efficacy of ABO major-mismatched transfusions as compared to matched transfusions. There was no analysis of clinical outcomes included in the study.

In comparison to the previously reported results in children, we did not detect significant differences in post-transfusion platelet count increments when comparing ABO compatible platelet transfusions to those with major or minor compatibility. Our subjects had generally been multiply transfused and our subgroup analysis showed no differences in platelet increment after transfusion for those who had received ≥ 30 mL/kg of platelet transfusions during their admission, prior to enrollment. In addition, in contrast to most other published studies, our population was quite diverse geographically and reports on regional differences. Since no accepted standard for ABO matching of platelet transfusions exists, practice varies significantly. In some European countries, the titers of antibodies to the A and B antigens are routinely measured in platelet units and then labeled as “high titer negative.”20 This allows for selection of these units specifically when incompatible platelets are transfused, thus theoretically minimizing the negative consequences. Similarly, there are regional differences in product preparation; for example, some platelet products are suspended in additive solution versus plasma.4 These variations may also affect the incremental changes in platelet counts observed.

Despite differences seen in platelet counts following transfusion of the ABO compatible versus ABO incompatible products, many argue that there is little evidence of differences in clinical outcomes shown in adults receiving platelet transfusions.9,10 A recently published systematic review evaluating both randomized controlled trials and observational studies regarding ABO incompatibility of platelet transfusions concluded that the clinical benefit of ABO matching was unclear since there is inconclusive data.21 Similarly, in a retrospective examination of the platelet transfusions administered during the Platelet Dose (PLADO) study, ABO matching was not predictive of the time to bleeding, if bleeding was to occur.22 We did not detect any differences in the rates of transfusion reactions between compatibility groups. An association between ABO compatibility and bleeding was not possible since our study did not include bleeding scores due to the lack of consensus regarding their value in children and the difficulty in obtaining these scores in an unfunded international study.

This study reports on ABO compatibility of platelet transfusions in the largest cohort of children to date. The analysis is the first to report the proportion of ABO compatible transfusions received in critically ill children. Additional strengths of our study relate to the population which represents a diverse cohort both in geography and pathophysiology. More than two-thirds of children received ABO-identical platelet transfusions. No patient characteristics were associated with the receipt of an ABO compatible platelet transfusion.

However, some limitations to our study exist. Although we reported on differences in the rates of transfusion reactions between compatibility groups, we did not assess for bleeding. Due to the inherent design of a point prevalence study, compatibility data was collected around one platelet transfusion and not around every platelet transfusion received by each enrolled subject during his/her admission; it is therefore unknown whether subjects received all ABO compatible versus a combination of compatible and incompatible transfusions. Some evidence suggests that ABO incompatible transfusions can affect the incremental platelet change following subsequent transfusions.23 As an observational study, post-transfusion platelet counts were assessed at the medical team’s discretion and thus not limited to a one hour post-transfusion assessment. We did not collect information on the variation of platelet count analyzers that was likely present between the hospitals. Additionally, each platelet transfusion contains a different number of platelets and we did not collect information on the number of platelets in each transfused aliquot. We also did not collect information on the ABO titer status of units transfused in Europe. We did not collect information on hemolysis (apart from acute hemolytic reactions during that transfusions) which may have occurred following the transfusion. Splenomegaly, an important clinical characteristic that can affect the post transfusion platelet counts, was not recorded.

CONCLUSIONS

In this large observational study in critically ill children, no differences were seen in incremental platelet count or transfusion reactions following the transfusion of ABO compatible platelets as compared to incompatible platelets. Because of limitations inherent to the study design, no definitive statement can be made. These results demonstrate that larger prospective studies must be performed to inform the need for ABO matching in critically ill children requiring platelet transfusions. Further confirmatory studies are needed that may require assessment of additional outcomes such as organ failure and clinical bleeding in critically ill children.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all the P3T investigators for their contribution, as well as the Clinical Translational Science Center (CTSC) at Weill Cornell Medical College

P3T investigators: Australia: Warwick Butt, Carmel Delzoppo (Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne); Simon Erickson, Elizabeth Croston, Samantha Barr (Princess Margaret Hospital, Perth); Elena Cavazzoni (Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney). Belgium: Annick de Jaeger (Princess Elisabeth Children’s University Hospital, Ghent). Canada: Marisa Tucci, Mary-Ellen French, Marion Ropars, Lucy Clayton (CHU Sainte-Justine, Montreal QC); Srinivas Murthy, Gordon Krahn (British Columbia Children’s Hospital, Vancouver, BC). China: Dong Qu, Yi Hui (Children’s Hospital Capital Institute of Pediatrics, Beijing). Denmark: Mathias Johansen, Anne-Mette Baek Jensen, Inge-Lise Jarnvig, Ditte Strange (Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen). India: Muralidharan Jayashree, Mounika Reddy (Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh); Jhuma Sankar, U Vijay Kumar, Rakesh Lodha (All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi). Israel: Reut Kassif Lerner, Gideon Paret (The Edmond and Lily Safra Children’s Hospital, Sheba Medical Center, Ramat Gan); Ofer Schiller, Eran Shostak, Ovadia Dagan (Schneider Children’s Medical Center, Petah Tikva); Yuval Cavari (Soroka University Medical Center, Beersheva). Italy: Fabrizio Chiusolo, Annagrazia Cillis (Bambino Gesu Children’s Hospital, Rome); Anna Camporesi (Children’s Hospital Vittore Buzzi, Milano). Netherlands: Martin Kneyber (Beatrix Children’s Hospital, Groningen); Suzan Cochius-den Otter, Ellen Van Hemeldonck (Erasmus MC- Sophia Children’s Hospital, Rotterdam). New Zealand: John Beca, Claire Sherring, Miriam Rea (Starship Child Health, Auckland). Portugal: Clara Abadesso, Marta Moniz (Hospital Prof. Dr. Fernando Fonseca, Amadora). Saudi Arabia: Saleh Alshehri (King Saud Medical City, Riyadh). Spain: Jesus Lopez-Herce, Irene Ortiz, Miriam Garcia (Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Maranon, Madrid); Iolanda Jordan (Institut de Recerca Hospital Sant Joan de Deu, Barcelona); J Carlos Flores Gonzalez (Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz); Antonio Perez-Ferrer, Ana Pascual-Albitre (La Paz University Hospital, Madrid). Switzerland: Serge Grazioli (University Hospital of Geneva, Geneva); Carsten Doell (University Children’s Hospital Zurich, Zurich). United Kingdom: Peter J. Davis (Bristol Royal Hospital for Children, Bristol); Ilaria Curio, Andrew Jones, Mark J. Peters (Great Ormond St Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London); Jon Lillie (Evelina London Children’s Hospital, London); Angela Aramburo, Medhat Shabana, Priya Ramachandran, Helena Sampaio (Royal Brompton Hospital, London); Kalaimaran Sadasivam (Royal London Hospital, Barts Health NHS Trust, London); Nicholas J Prince (St George’s Hospital, London); Hari Krishnan Kanthimathinathan (Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Birmingham); Ricardo Garcia Branco (Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Trust, Cambridge); Kim L. Sykes, Christie Mellish (University Hospital Southampton, Southampton); Avishay Sarfatti, James Weitz (Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford). United States: Ron C. Sanders Jr, Glenda Hefley (Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Little Rock, AR); Rica Sharon P. Morzov, Barry Markovitz (Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA); Anna Ratiu, Anil Sapru (Mattel’s Children’s Hospital, Los Angeles, CA); Allison S. Cowl (Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, CT); E. Vincent S Faustino (Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT); Shruthi Mahadevaiah (University of Florida Shands Children’s Hospital, Gainesville, FL); Fernando Beltramo (Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, Miami, FL); Asumthia S Jeyapalan, Mary K Cousins (University of Miami/Holtz Children’s Hospital, Miami, FL); Cheryl Stone, James Fortenberry (Children’s Hospital of Atlanta, Atlanta, GA); Neethi P. Pinto, Chiara Rodgers, Allison Kniola (The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL); Melissa Porter, Erin Owen, Kristen Lee, Laura J. Thomas (University of Louisville, Kosair Charities Pediatric Clinical Research Unit, and Norton Children’s Hospital, Louisville, KY); Melania M Bembea, Ronke Awojoodu (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD); Daniel Kelly, Kyle Hughes (Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA); Zenab Mansoor, Carol Pineda (Tufts Floating Hospital for Children, Boston, MA); Phoebe H Yager, Maureen Clark (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA); Scot T. Bateman (UMass Memorial Children’s Medical Center, Worcester, MA); Kevin W. Kuo, Erin F. Carlton (C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI); Brian Boville, Mara Leimanis (Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, Grand Rapids, MI); Marie E. Steiner, Dan Nerheim (University of Minnesota Masonic Children’s Hospital, Minneapolis, MN); Kenneth E. Remy, Lauren Langford, Melissa Schicker (Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO); Marcy N Singleton, J Dean Jarvis, Sholeen T Nett (Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH); Shira Gertz (Hackensack University Medical Center, Hackensack, NJ); Ruchika Goel (New York Presbyterian Hospital – Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY); James S. Killinger, Meghan Sturhahn (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY); Margaret M. Parker, Ilana Harwayne-Gidansky (Stony Brook Children’s Hospital, Stony Brook, NY); Laura A. Watkins (Cohen Children’s Medical Center, Northwell Health, Queens, NY); Gina Cassel, Adi Aran, Shubhi Kaushik (The Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, NY); Andy Y. Wen (NYU Langone Medical Center, NYU School of Medicine, New York, NY); Amanda B. Hassinger (Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo, Buffalo, NY); Caroline P. Ozment, Candice M. Ray (Duke Children’s Hospital and Health Center, Durham, NC); Michael C. McCrory, Andora L Bass (Wake Forest Brenner Children’s Hospital, Winston-Salem, NC); Michael T Bigham, Heather Anthony (Akron Children’s Hospital, Akron, OH); Jennifer A. Muszynski, Jill Popelka (Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH); Julie C. Fitzgerald, Susan Doney Leonard (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA); Neal J. Thomas, Debbie Spear (Penn State Hershey Children’s Hospital, Hershey, PA); Whitney E. Marvin (Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC); Arun Saini; Alina Nico West (University of Tennessee Health Science Center and Le BonHeur Children’s Hospital, Memphis, TN); Jennifer McArthur, Angela Norris, Saad Ghafoor, Ashlea Anderson (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN); Tracey Monjure, Kris Bysani (Medical City Children’s Hospital, Dallas, TX); LeeAnn M. Christie (Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, TX); Laura L Loftis (Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX); Andrew D. Meyer, Robin Tragus, Holly Dibrell, David Rupert (University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX); Claudia Delgado-Corcoran, Stephanie Bodily (University of Utah, Primary Children’s Hospital, Salt Lake City, UT); Douglas Willson (Children’s Hospital of Richmond at VCU, Richmond, VA); Leslie A. Dervan (Seattle Children’s, University of Washington, Seattle, WA); Sheila J. Hanson (Medical College of Wisconsin/ Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI); Scott A. Hagen, Awni M. Al-Subu (University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI).

Financial Support: This project was supported in part by funds from the Clinical Translational Science Center (CTSC), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) grant #UL1-TR000457.

Drs. Cushing and Spinella received funding from Cerus Corporation.

Footnotes

Copyright form disclosure: The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nellis ME, Karam O, Mauer E, et al. Platelet Transfusion Practices in Critically Ill Children. Critical Care Medicine 2018; 46(8):1309–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooling LL, Kelly K, Barton J, Hwang D, Koerner TA, Olson JD. Determinants of ABH expression on human blood platelets. Blood 2005; 96:3356–3364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Issitt PD, Anstee DJ. The ABO and H blood group system. Applied Blood Group Serology 4th ed. Durham, NC: Montgomery Scientific Publications; 1998:175–246. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lozano M, Heddle N, Williamson LM, Wang G, AuBuchon JP, Dumont LJ for the Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion (BEST) Collaborative. Transfusion 2010; 50: 1743–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooling L ABO and platelet transfusion therapy. Immunohematology 2007; 23:20–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henrichs KF, Howk N, Masel DS, et al. Providing ABO-identical platelets and cryoprecipitate to (almost) all patients: approach, logistics, and associated decreases in transfusion reaction and red blood cell alloimmunization incidence. Transfusion 2012; 52:635–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pavenski K, Warkentin TE, Shen H, et al. Post transfusion platelet count increments after ABO-compatible versus ABO-incompatible platelet transfusions in noncancer patients: an observational study. Transfusion 2010; 50:1552–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Julmy F, Ammann RA, Taleghani BM, Fontana S, Hirt A, Leibundgut K. Transfusion efficacy of ABO major-mismatched platelets (PLTs) in children is inferior to that of ABO-identical PLTs. Transfusion 2009; 49:21–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leteutre S, Duhamel A, Salleron J, et al. PELOD-2: an update of the Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction score. Crit Care Med 2013; 41:1761–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solves P, Carpio N, Balaguer A, et al. Transfusion of ABO non-identical platelets does not influence the clinical outcome of patients undergoing autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood Transfus 2015; 13:411–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin Y, Callum JL, Coovadia AS, Murphy PM. Transfusion of ABO non-identical platelets is not associated with adverse clinical outcomes in cardiovascular surgery patients. Transfusion 2002; 42:166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aster RH. Effect of anticoagulant and ABO incompatibility on recovery of transfused human platelets. Blood 1965; 26:732–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duguesnoy RJ, Anderson AJ, Tomasulo PA, Aster RH. ABO compatibility and platelet transfusions of alloimmunized thrombocytopenic patients. Blood 1979; 70:23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heal JM, Blumberg N, Masel D. An evaluation of cross-matching, HLA ad Abo matching for platelet transfusions to refractory patients. Blood 1987; 70:23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klumpp TR, Herman JH, Innis S, et al. Factors associated with response to platelet transfusion following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 1996; 17:1035–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heal JM, Rowe JM, Blumberg N. ABO and platelet transfusion revisited. Ann Hematol 1993; 66:309–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carr R, Hutton JL, Jenkins JA, Lucas GF, Amphlett NW. Transfusion of ABO-mismatched platelets leads to early platelet refractoriness. Br J Haematol 1990; 75:408–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heal JM, Masel D, Rowe JM, Blumberg N. Circulating immune complexes involving the ABO system after platelet transfusion. Br J Haematol 1993; 85:566–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zaffuto BJ, Conley GW, Connolly GC, et al. ABO-immune complex formation and impact on platelet function, red call structural integrity and haemostasis: an in vitro model of ABO non-identical transfusion. Vox Sang 2016; 110:219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maclennan S International Forum. Transfusion of apheresis platelets and ABO groups. Vox Sang 2005; 88:218–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shehata N, Tinmouth A, Naglie G, et al. ABO-identical versus non-identical platelet transfusion: a systematic review. Transfusion 2009; 49:2442–2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Triulzi DJ, Assmann SF, Strauss RG et al. The impact of platelet transfusion characteristics on post-transfusion platelet increments and clinical bleeding in patients with hypo-proliferative thrombocytopenia. Blood 2012; 23:5553–5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee EJ, Schiller CA. ABO compatibility can influence the results of platelet transfusion. Results of a randomized trial. Transfusion 1989; 29(5): 384–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]