SUMMARY

Systems consolidation is a process by which memories initially require the hippocampus for recent long-term memory (LTM) but then become increasingly independent of the hippocampus and more dependent on the cortex for remote LTM. Here we study the role of phosphodiesterase 11A4 (PDE11A4) in systems consolidation. PDE11A4, which degrades cAMP and cGMP, is preferentially expressed in neurons of CA1, the subiculum, and the adjacently connected amygdalohippocampal region. In male and female mice, deletion of PDE11A enhances remote LTM for social odor recognition and social transmission of food preference (STFP) despite eliminating/silencing recent LTM for those same social events. Measurement of a surrogate marker of neuronal activation (i.e., Arc mRNA) suggests the recent LTM deficits observed in Pde11 knockout mice correspond with decreased activation of ventral CA1 relative to wild-type littermates. In contrast, the enhanced remote LTM observed in Pde11a knockout mice corresponds with increased activation and altered functional connectivity of anterior cingulate cortex, frontal association cortex, parasubiculum, and the superficial layer of medial entorhinal cortex. The apparent increased neural activation observed in prefrontal cortex of Pde11a knockout mice during remote LTM retrieval may be related to an upregulation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits NR1 and NR2A. Viral restoration of PDE11A4 to vCA1 alone is sufficient to rescue both the LTM phenotypes and upregulation of NR1 exhibited by Pde11a knockout mice. Together our findings suggest remote LTM can be decoupled from recent LTM, which may have relevance for cognitive deficits associated with aging, temporal lobe epilepsy or transient global amnesia.

Keywords: transient amnesia, cyclic nucleotide, phosphodiesterase, system consolidation, systems consolidation, retrieval, social, remote memory, cAMP, cGMP, consolidation, protein synthesis, glutamate, Kamin effect, memory lapse

eTOC Blurb:

Is memory linear? Must a recent long-term memory form in order to manifest a remote long-term memory for that same event? Pilarzyk et al. show that deleting PDE11A4 from ventral CA1 of hippocampus strengthens social memories 7 days after training despite causing amnesia 24 hours after training. Interestingly, non-social memories remain unaffected.

INTRODUCTION

Systems consolidation is a process by which long-term memories (LTMs) for certain types of information initially require the hippocampus (i.e., “recent” LTM) but then become increasingly independent of the hippocampus and more dependent on the cortex (i.e., “remote” LTM), arguably at the expense of the memory losing some detail [1, 2]. Studies of contextual fear conditioning suggest elements of a memory are initially encoded simultaneously within both the hippocampus and cortex; however, only the hippocampal trace is sufficiently mature to support retrieval of a recent memory [3]. Hippocampus-mediated “replay” of the recent memory to the cortex is then required to permanently mature the cortical engram to the point of sustaining remote retrieval, at which time the hippocampus trace is erased/silenced [1-3]. This suggests that the transition from recent LTM to remote LTM is a serial process; that is, you must have recent LTM in order to have remote LTM. Although it has been suggested that the dynamics of systems consolidation described above for fear memories should extrapolate to other episodic-like memories [2], we show here it is possible to exhibit enhanced remote LTM for social experiences in absence of any recent LTM for those same events.

Our lab focuses on an enzyme called phosphodiesterase 11A (PDE11A) and its role in the neurobiological substrates of social memory and other social behaviors. Lesioning of ventral CA1 (vCA1) and ventral subiculum impairs the formation of social memories [4, 5] as does ventral hippocampal knock down of cAMP response element binding protein [6]. Further, optogenetic studies have shown that vCA1 projections to the nucleus accumbens are required for social memory [7]. Given that PDE11A is mostly highly expressed in vCA1/subiculum, regulates cyclic nucleotide signaling, and is expressed in neurons that project from vCA1 to accumbens, it is perhaps not surprising that PDE11A appears to play a critical role in the formation of social memories [8, 9].

Previously, we showed that Pde11a knockout mice show normal short-term memory (STM) for social experiences but impaired recent LTM apparently due to impaired protein synthesis [8, 9]. Interestingly, recent LTM impairments caused by the selective/preferential loss of protein synthesis in the hippocampus can be transient (c.f., [10]). Further, transient global amnesia has been reported in patients treated with drugs known to have off-target activity at PDE11A [11, 12]. As such, we determined if deletion of Pde11a actually produces transient amnesia for social memories as opposed to permanent memory loss. Surprisingly, we show that deletion of Pde11a paradoxically improves remote LTM for social experiences in adult mice despite impairing recent LTM for those same events.

RESULTS

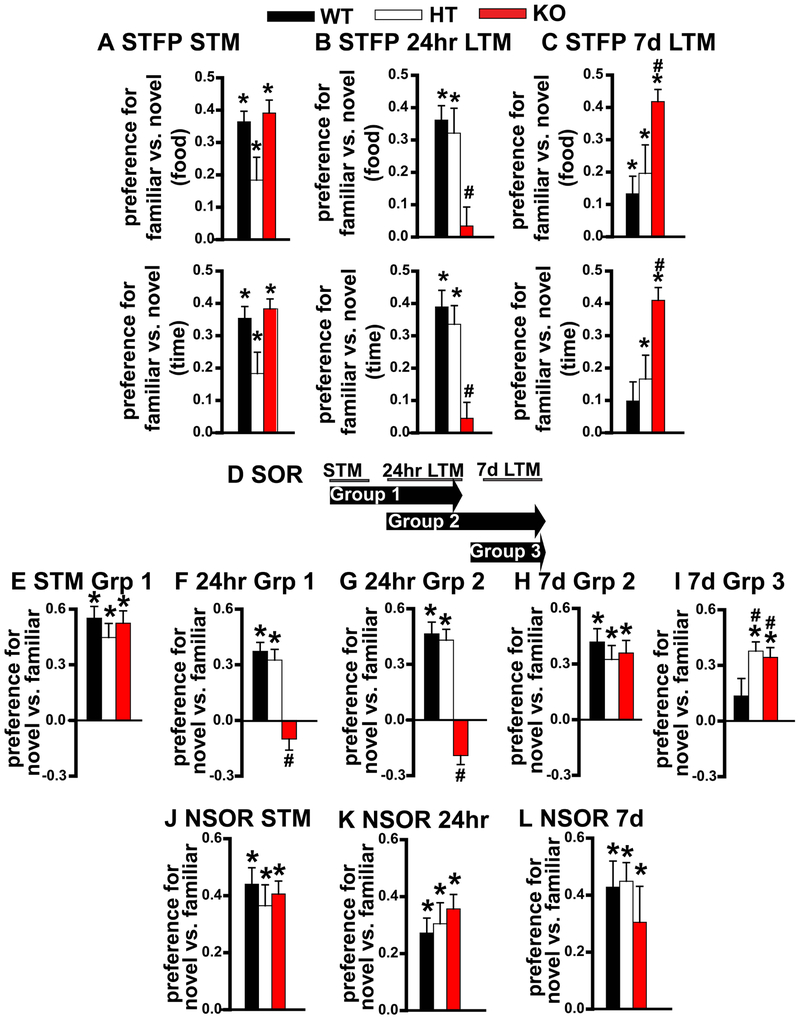

Deletion of PDE11A produces transient amnesia for social transmission of food preference (STFP) in adult mice.

To determine if PDE11A deletion differentially affects recent vs. remote LTM, we trained mice on STFP (Figure S1A). STFP requires subjects to make an association between the odor of food laced with a household herb/spice (i.e., a non-social odor) and pheromones in the breath of their cage mate (i.e., a social odor). A composite analysis of multiple cohorts of mice (see Figure S2 for breakdown of each cohort) shows that adult Pde11a knockout mice showed intact STM, impaired recent LTM and enhanced remote LTM for STFP, the latter apparently by virtue of some weakening of the memory in adult wild-type mice (Figure 1A-B and S3A-C). In select cohorts, adult Pde11a heterozygous mice also exhibited a transient deficit, with somewhat weaker STM relative to wild-type littermates; however, this effect did not remain significant when all cohorts were combined. In each study, there was no difference between genotypes in terms of the total amount of food eaten. Thus, adult Pde11a mutant mice exhibit transient amnesia for social associative memories.

Figure 1. Deletion of PDE11A produces transient amnesia for social transmission of food preference (STFP) and social odor recognition (SOR) but not non-social odor recognition (NSOR) in adult female and male mice.

A) Pde11a knockout (KO) mice (n=37) showed intact short-term memory (STM) for STFP (see Figure S1 for method detail), whereas, Pde11a heterozygous (HT) mice (n=33) showed a trend toward impaired STM relative to adult wild-type (WT) mice (n=32) (both failed equal variance; food: H(2)=5.51, P=0.063; time: H(2)=5.04, P=0.081). B) Pde11a heterozygous mice (n=24) showed strong recent long-term memory (LTM, 24 hours after training) relative to adult wild-type littermates (food, n=27; time, n=25); however, Pde11a knockout mice (food, n=30; time, 29) showed no recent LTM for STFP (food: F(2,75)=9.61, P=0.0002; time: F(2,72)=13.04, P=<0.0001). C) Despite these deficits at earlier time points, adult Pde11a heterozygous (n=24) and particularly adult Pde11a knockout mice (food, n=41; time, n=36) showed improved remote LTM for STFP (i.e., 7 days after training) relative to adult wild-type littermates (food, n=35; time, n=28) due to an apparent weakening of the memory in wild-type mice (failed equal variance; food: H(2)=13.48, P=0.0011; time: F(2,78)=8.84, P=0.0003). See Figure S2 for details regarding testing/retesting in STFP. D) STM, recent memory LTM, and remote LTM for SOR were assessed in 3 groups of mice. Group 1 was retested for 24 hour LTM on the same day Group 2 was retested for 7 day LTM. Mice in group 3 were trained/tested at a completely separate time. E) Group1 Pde11a knockout mice that showed normal STM (n=20/genotype; F(2,54)=0.61, P=0.55) went on to demonstrate F) impaired recent LTM (failed normality; H(2)=24.59, P<0.0001). G) Group 2 Pde11a knockout mice (n=21) tested for the first time 24 hours after training similarly showed impaired recent LTM relative to Pde11a heterozygous and wild-type littermates (n=20 each; failed normality; H(2)=31.17, P<0.0001), yet H) normal remote LTM (F(2,55)=0.43, P=0.65); see Figure S5 for replication). I) Surprisingly, Group 3 Pde11a heterozygous (n=13) and knockout mice (n=15) tested for the first time 7d after training actually showed slightly stronger remote LTM relative to wild-type mice (n=15; F(2,37)=3.60, P=0.037). In contrast, J) Pde11a deletion did not affect 2-bead NSOR memory (see Figure S5 for replication with 3-bead NSOR). Adult Pde11a wild-type, heterozygous and knockout mice showed equally strong STM (WT and KO, n=19; HT, n=11; F(1,43)= 0.258, P=0.774), K) recent LTM (WT, n=12; HT, n=10; KO, n=11; F(2,30)= 0.553, P=0.581) and L) remote LTM for NSOR (n=18/genotype, effect of bead: F(1,24)=22.55, P<0.001). Note, NSOR and STFP memories were only tested once. For NSOR, each cohort was naïve. See Table S1 for one-sample t-tests, Table S2 for other post hoc analyses, Figure S3 for novel vs. familiar plotted as a % of total (as previously reported [8]), and Figure S4 for total sniffing time that revealed a sex effect in SOR but no genotype effect. *significantly >0 (=memory), P<0.04-0.0001; Post hoc, #vs. WT, P≤0.035-0.0001. Data plotted as means ±SEMs.

Deleting PDE11A produces transient amnesia for social odor recognition (SOR) in adult mice.

Next we determined if Pde11a deletion also produces transient amnesia for social recognition memories using SOR (Figure S1B). As we previously published [8], Pde11a knockout mice showed normal STM for SOR (Figure 1E and S3E), but those same mice went on to show no recent LTM 24 hours after training (Figure 1F and S3F). A second cohort of Pde11a knockout mice that were tested for the first time at 24 hours similarly showed no recent LTM (Figure 1G and S3G; see Figure S5A-E for replicate study) but went on to demonstrate strong remote LTM 7 days after training (Figure 1H and Figure S3H). Importantly, the ability of Pde11a knockout mice to recover remote SOR LTM did not require a previous memory test. When adult mice were tested for the first time 7 days after training, Pde11a heterozygous and knockout mice showed slightly enhanced remote LTM for SOR relative to wild-type littermates (Figure 1I). In contrast, adult Pde11a wild-type, heterozygous and knockout littermates demonstrated equally strong STM, recent LTM and remote LTM for non-social odor recognition (NSOR, Figure S1C; Figure 1J-L and Figure S6F-J for replicate study). Although males typically spent less total time investigating the social odors than the females, there was not a consistent difference between the sexes in terms of total time spent investigating the non-social odors (Figure S4), and there was no significant effect of genotype in any experiment. Together, these studies show that Pde11a deletion is not simply affecting all olfactory-based or recognition memories, but rather is specifically producing transient amnesia for recognition and associative memories involving social stimuli.

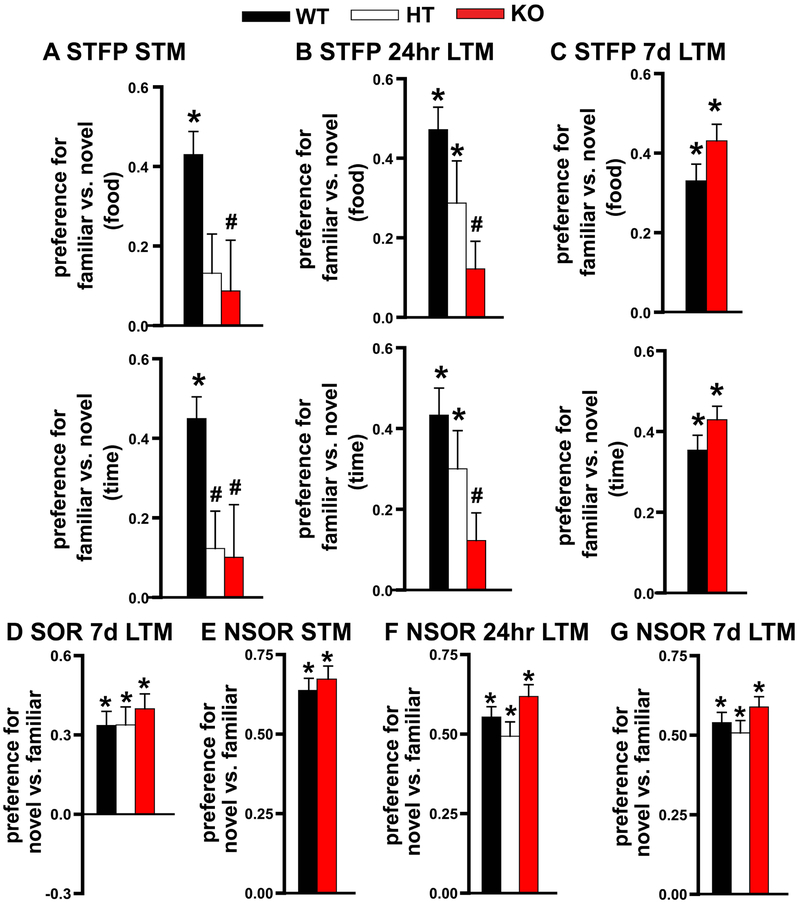

Deleting PDE11A also produces transient amnesia for social memories in adolescent mice.

Previously, we reported that PDE11A4 expression dramatically increases between postnatal days 7 and 28, and that adolescent Pde11a knockout mice demonstrate recent LTM deficits for SOR and STFP 24 hour following training [8]. Therefore, we tested here if memory deficits that appear in the adolescent mice are transient like those observed in the adult mice. As observed in adult mice, Pde11a heterozygous and knockout mice exhibit transient amnesia for STFP (Figure 2A-C). That said, performance of adolescent Pde11a knockout mice 7 days after training was not significantly better than wild-type littermates (food post hoc: P=0.095), as it had been in the adults. Adolescent Pde11a knockout mice tested for the first time similarly demonstrate transient amnesia for SOR but not NSOR (Figure 2D-G, see [8] for 24-hour SOR deficit). Thus, both adult and adolescent Pde11a mutant mice exhibit transient amnesia for social memories; however, these groups differ with regard to the timing of deficits and the degree of improvement possibly due to the differential maturational state of relevant circuits.

Figure 2. Deletion of PDE11A produces transient amnesia for STFP and SOR but not NSOR in adolescent male and female mice.

A) Adolescent Pde11a heterozygous (n=15) and knockout mice (n=14) showed impaired STM for STFP (see Figure S1 for method detail) relative to adolescent wild-type littermates (n=16; food: F(2,39)=3.64, P=0.036; time: F(2,39)=4.13, P=0.023). B) This deficit recovers by 24 hours in adolescent Pde11a heterozygous mice (n=16) but not adolescent Pde11a knockout mice (n=24; WT, n=17; (both fail normality) food: H(2)=9.32, P=0.0094; time: H(2)=9.96, P=0.0069). Data represented in 2B top was previously reported in a different format in [8]. C) 7d after training, however, adolescent Pde11a knockout mice (n=26) showed intact remote LTM for STFP (WT, n=26; food: F(1,48)=2.17, P=0.148; time: F(1,48)=1.89, P=0.175). Although 7d STFP performance was slightly elevated in the adolescent knockout mice relative to wild-type littermates, the difference between genotypes was not statistically significant (e.g. food post hoc, P=0.095). The fact that adult Pde11a knockout mice showed significantly stronger 7d LTM for STFP relative to wild-type mice but adolescent mice did not may be due to the fact that performance of the adolescent wild-type mice did not weaken to the same extent as was seen in the adults (see Figure 1C). The weakening in adults is consistent with the fact that STFP memories are highly vulnerable to age-related decline in rodents [84]. D) Previously [8], we showed that adolescent Pde11a knockout mice also show no recent LTM for SOR; however, here we show adolescent Pde11a knockout mice (n=26) tested for the first time 7 days after training show remote LTM for SOR that is equivalent to that observed in heterozygous (n=32) and wild-type littermates (n=25; fails normality, H(2)=0.03, P=0.99). E) Separate cohorts of adolescent Pde11a wild-type, heterozygous and knockout mice also show equivalent NSOR when tested for short-term memory (n=18/genotype; F(1,32)=0.23, P=0.63), F) recent LTM 24 hr after training (WT, n=24; HT, n=17; KO, n=16; F(1,51)=2.01, P=0.15), and G) remote LTM 7 days after training (WT, n=17; HT, n=24; KO, n=18; F(1,56)=1.33, P=0.27). See Table S1 for one-sample t-tests, and Table S2 for other post hoc analyses. *significantly >0 (=memory), P<0.02-0.0001; Post hoc, #vs. WT, P=0.032-0.005. Data plotted as means ±SEMs.

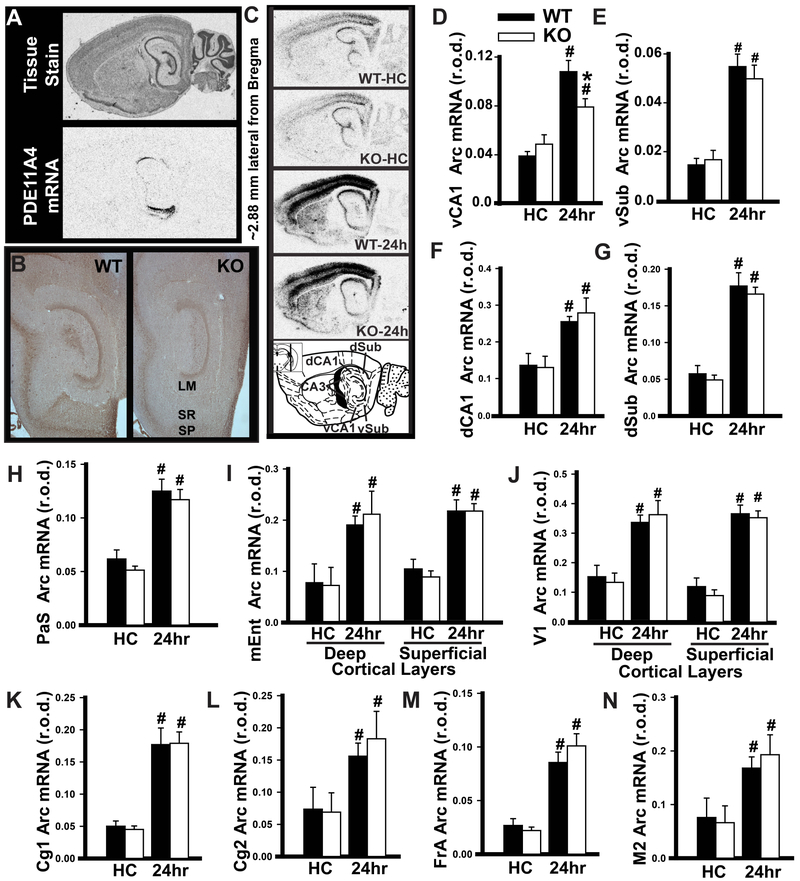

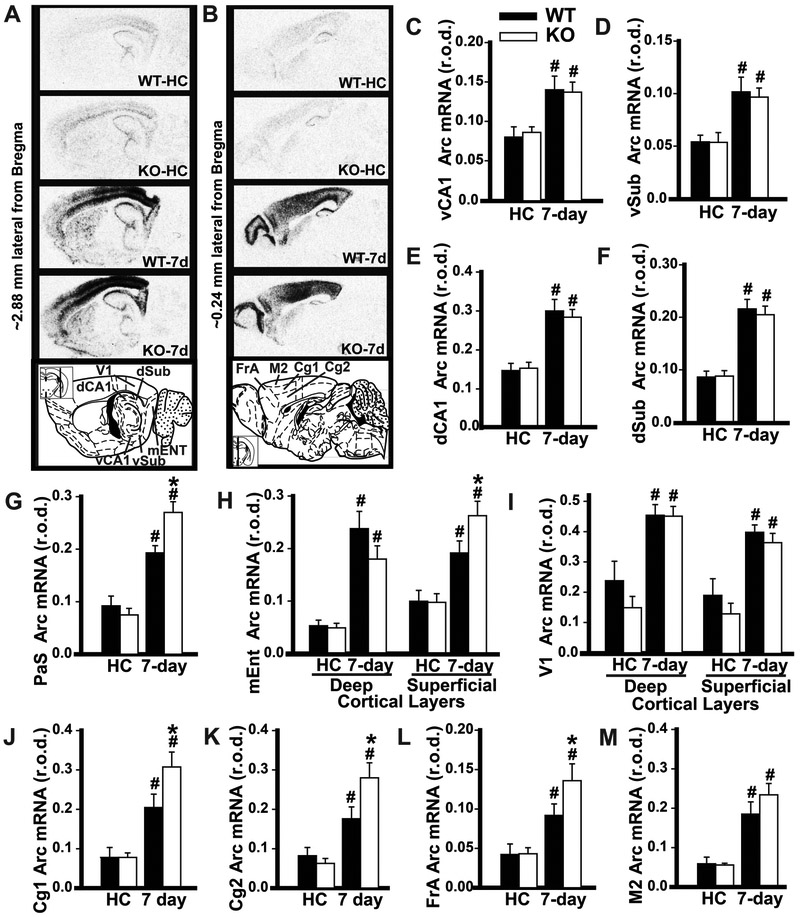

Adult PDE11A knockout mice show altered neural activation and connectivity during the retrieval of an STFP LTM.

To identify possible differences in brain activation patterns in Pde11a wild-type vs. knockout mice, mice were tested on recent vs. remote LTM for STFP and brains were labeled for the immediate early gene activity-regulated cytoskeleton associated protein (Arc; Figure S6). A similar experiment was also attempted to image activity underlying SOR retrieval. Unfortunately, the 2-minute SOR memory test was insufficiently long to differentiate Arc levels between trained and home-caged mice using our autoradiographic technique, which is a limitation of the present study. Our analyses focused on brain regions known to play a role in systems consolidation of STFP or other hippocampus-dependent tasks, namely the PDE11A4-expressing hippocampal subfields (i.e., CA1 and subiculum), parasubiculum, anterior cingulate cortex, frontal association cortex as a subsection of medial prefrontal cortex, and the superficial layers of medial entorhinal cortex. To determine if genotype effects were selective for these systems consolidation-related brain regions, we also measured Arc expression in motor and visual cortex. Relative to Pde11a wild-type mice, Pde11a knockout mice showed reduced expression of Arc in vCA1 during the retrieval of a recent STFP LTM, but no changes elsewhere (Figure 3). During the retrieval of a remote STFP LTM, Pde11a knockout mice showed equivalent hippocampal Arc expression relative to wild-type littermates, but increased Arc expression in parasubiculum, the superficial layers of medial entorhinal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and frontal association cortex. These differences in extra-hippocampal Arc expression appear to be specific as there was no genotype effect in visual nor motor cortex (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Relative to adult wild-type littermates, Pde11a knockout mice show reduced activation of ventral CA1 (vCA1) during the retrieval of a recent LTM for STFP.

A) Pde11a4 mRNA and B) protein expression are restricted to CA1 stratum pyramidale (SP) and radiatum (SR), the subiculum (Sub), and the amygdalohippocampal area (just below CA1). Note the absence of PDE11A4 protein in CA2/CA3 as well as the lacunosum moleculare (LM). C) Autoradiographs for activity-regulated cytoskeleton associated protein (Arc) mRNA in home-caged controls (HC) and mice retrieving a 24hr STFP LTM (24hr, n =12/group; see Figure S6 for method detail). D) Pde11a knockout mice showed lower retrieval-induced Arc expression in vCA1 relative to wild-type littermates (F(3,41)=19.35, FDR-P<0.0001), but equivalent expression in E) ventral subiculum (vSub, F(3,44)=22.63, FDR-P<0.0001), F) dCA1 (F(3,44)=6.33, FDR-P=0.0002), G) dorsal subiculum (dSub, F(3,44)=46.05, FDR-P<0.0001), H) parasubiculum (PaS, F(3,44)=18.89, FDR-P<0.0001), I) the deep (H(3,44)=25.01, FDR-P=0.0002) and superficial layers (H(3,44)=28.38, FDR-P=0.0002) of medial entorhinal cortex (mEnt), J) the deep (H(3,44)=24.35, FDR-P=0.0004) and superficial layers (F(3,44)=33.20, FDR-P<0.0001) of visual cortex (V1), K,L) anterior cingulate subfields 1 and 2 (Cg1, H(3,42)=30.94, FDR-P<0.0001, Cg2: H(3,42)=20.23, FDR-P=0.0032), M) frontal association cortex (FrA, H(3,43)=28.64, FDR-P=0.0002), and N) motor cortex (M2, H(3,43)=22.20, FDR-P=0.003). See Table S2 for individual post hoc analyses. Post hoc, #vs. home cage within genotype (HC), P<0.01-0.001; Post hoc,*vs WT within behavioral group, P=0.002. Brightness and contrast of autoradiographic images adjusted for graphical clarity. Data plotted as means ±SEMs.

Figure 4. Relative to adult wild-type littermates, Pde11a knockout mice show enhanced activation of extrahippocampal systems consolidation-related brain regions during retrieval of a remote LTM for STFP.

A,B) Arc mRNA autoradiographs (see Figure S6 for method detail) home-cage controls (HC) (n=7/genotype) and mice retrieving of a 7 day STFP LTM (7d, n =8/genotype). Relative to Pde11a wild-type mice, knockout mice showed equivalent retrieval-induced Arc expression in C) vCA1 (F(3,19)=7.82, FDR-P=0.001), D) vSub (F(3,19)=12.20, FDR-P=0.0001), E) dCA1 (F(3,19)=25.55, FDR-P<0.0001), and F) dSub (F(3,19)=29.84, FDR-P<0.0001). Relative to Pde11a wild-type mice, knockout mice showed significantly stronger retrieval-induced Arc expression in G) parasubiculum (PaS, F(3,29)=29.05, FDR-P<0.0001) and H) the superficial layer of medial entorhinal cortex (mEnt, F(3,29)=30.37, FDR-P<0.0001), but not the deep layers of Ent (F(3,19)=14.95, FDR-P<0.0001) nor I) visual cortex (V1, F(3,19)=17.48, FDR-P<0.0001). Relative to Pde11a wild-type mice, knockout mice also showed significantly stronger retrieval-induced Arc expression in J) anterior cingulate 1 (Cg1, F(3,29)=16.16, FDR-P<0.0001), K) Cg2 (F(3,29)=13.47, FDR-P<0.0001), and L) frontal association cortex (FrA, F(3,29)=10.15, FDR-P=0.0004), but not M) motor cortex (M2, F(3,19)=11.69, FDR-P=0.0002). See Table S2 for individual post hoc analyses. Post hoc, #vs HC within genotype, P<0.025-0.001; Post hoc, *vs WT within behavioral group, P=0.037-0.003. Brightness and contrast of autoradiographic images adjusted for graphical clarity. Data plotted as means ±SEMs.

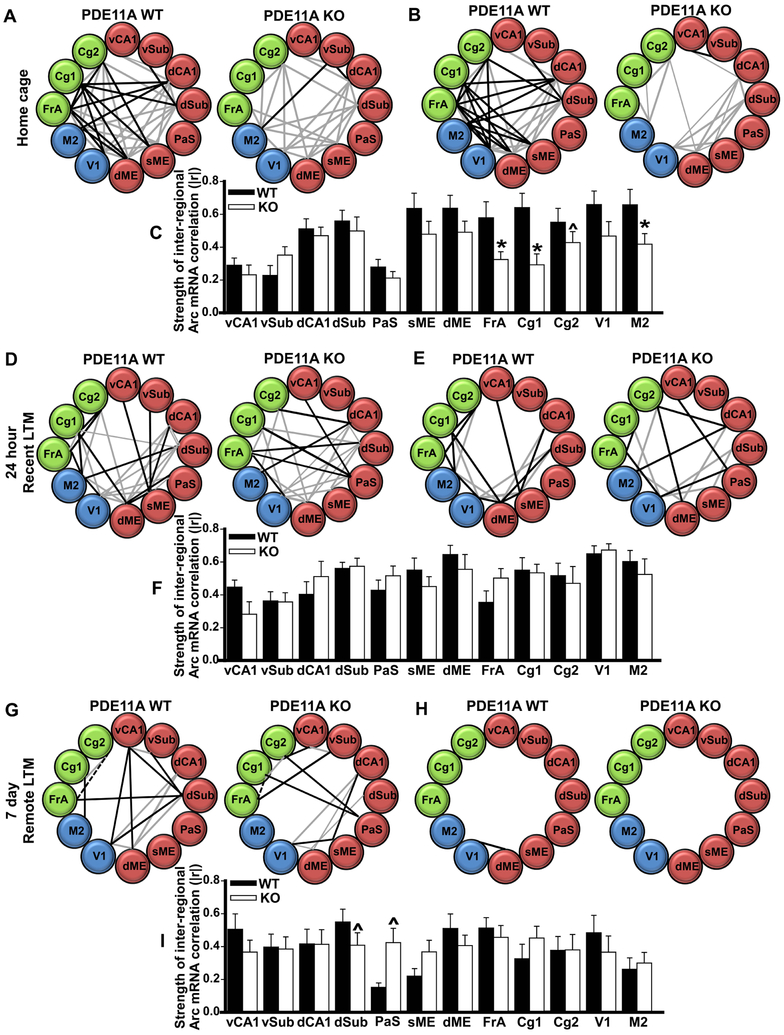

Social memory formation is not only associated with increased activity within discrete brain regions, but also a shift in the degree to which activity across brain regions is correlated [13]. This correlation of activity across brain regions is referred to as “functional connectivity” and can arise from immediate or remote neurophysiological events [14]. Correlational analyses of activity-regulated immediate-early gene expression is used to assess functional connectivity in rodents (e.g., [15]). Therefore, we assessed functional connectivity by correlating Arc mRNA levels between brain regions and determining if the strength of those correlations differed between Pde11a wild-type versus knockout mice (Data S1). Graphic representation of significant correlations between brain regions shows a distinct reduction in functional connectivity in frontal cortical regions of home-caged Pde11a knockout mice relative to wild-type littermates (Figure 5A-C). Interestingly, such a global reduction in functional connectivity in the Pde11a knockout mice relative to wild-type mice is not observed during the retrieval of either a recent or remote LTM for STFP. Instead, there appears to be a shift in the pattern of connectivity between genotypes (Figure 5D-I). Together, these data suggest that deletion of Pde11a is not only changing how information is processed within the hippocampus, but also how information is processed across circuits as a whole.

Figure 5. Patterns of functional connectivity differ by both memory-retrieval period and Pde11a genotype in adult mice.

Correlational analyses were conducted comparing Arc expression between brain regions (see Figure S6 for method detail and Data S1 for each r and P-value). A,B,D,E,G,H) Black lines indicate significant correlations unique to that genotype, whereas, gray lines indicate correlations that are shared between genotypes for the same retrieval period (thick lines indicate P<0.05, thin lines indicate P=0.051-0.079—only shown when correlation reaches P<0.05 in other genotype). Solid lines indicate positive correlations, dashed lines indicate negative correlations. A,D,G) represent significant raw P-values as reported in [13] (with 66 inter-regional correlations per group and a significance cutoff of P<0.05, 3-4 false positives per group can be expected); whereas, B,E,H) represent only P-values that remain significant following FDR correction for multiple comparisons. C,F,I) represent a comparison of the strength of all inter-regional correlations for a given brain region and are graphed as mean ±SEM of the absolute value of the raw r (|r|). A-B) In the home cage, Pde11a knockout mice showed far less functional connectivity relative to wild-type mice, particularly in C) FrA (t(10)=3.15, raw-P=0.01 and FDR-P=0.04), Cg1 (t(10)=5.11, raw-P=0.0005 and FDR-P=0.0055), Cg2 (t(10)=2.37, raw-P=0.039; FDR-P=0.117) and M2 (t(10)=3.23, raw-P=0.009 and FDR-P=0.04). D-F) In striking contrast, there was not an overall reduction in functional connectivity in the PDE11A knockout versus wild-type mice when undergoing STFP retrieval 24 hours after training. Rather, there appears to be a shift in the functional connectivity of brain regions. For example, in wild-type mice, vCA1 correlates with sME; whereas, in knockout mice, vCA1 correlates with PaS. G-H) A similar shift in retrieval-induced functional connectivity is also seen between PDE11A knockout vs. wild-type mice 7 days after training, with some suggestion of a change in the functional connectivity of I) PaS (t(10)=2.72, raw-P=0.022 and FDR-P=0.26) and dSub (t(10)=2.36, raw-P=0.04 and FDR-P=0.37). vCA1—ventral CA1, vSub—ventral subiculum, dCA1—dorsal CA1, dSub—dorsal subiculum, PaS—parasubiculum, sME—superficial layer of medial entorhinal cortex, dME—deep layer of medial entorhinal cortex, V1—visual cortex, M2—motor cortex, FrA—frontal association cortex, Cg1—anterior cingulate cortex subfield 1, Cg2-- anterior cingulate cortex subfield 2. *both raw- and FDR-P≤0.04, ^only raw-P≤0.04.

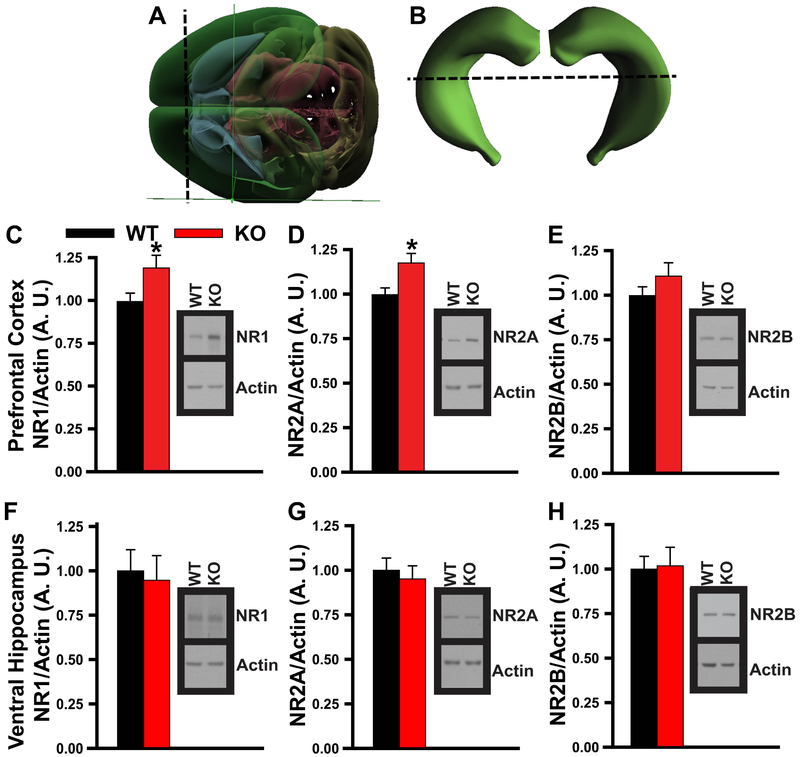

Deletion of PDE11A increases N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit expression in prefrontal cortex but not the ventral hippocampal formation (VHIPP) in adult mice.

Little has been characterized of the molecular mechanisms underlying systems consolidation, but several studies have implicated N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor signaling (c.f., [1]). Previous findings suggest that PDE11A4 may control pools of cyclic nucleotides that are upstream and/or downstream of this receptor. Pde11a knockout mice exhibit altered sensitivity to MK-801, an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, and PDE11A4 expression in rodent hippocampus correlates with phosphorylation of CaMKIIα, an enzyme that is downstream of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors [9, 16]. As such, we determined if increased expression of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits could account for the phenotypes observed in Pde11a knockout mice. Guided by the Arc data (Figures 3-4), we focused on prefrontal cortex and VHIPP. We focused on the NR1, NR2A and NR2B subunits as NR1 is required for the maintenance of remote memories [17] and NR2A and NR2B are required for synaptic plasticity in prefrontal cortex (e.g., [18]). Pde11a knockout mice showed higher expression of both NR1 and NR2A in prefrontal cortex relative to wild-type littermates but no change in VHIPP (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Deletion of PDE11A increases expression of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subunits in prefrontal cortex but not ventral hippocampus of adult mice.

A) For purposes of this experiment, prefrontal cortex was defined as cortical tissue anterior to the caudate-putamen (brain shown from above; dissection indicated by perforated black line). B) Ventral hippocampus was defined as the lower 40-45% (hippocampus shown in the caudal plane and dissection indicated by the perforated black line). In prefrontal cortex, Pde11a knockout (KO) mice show C) increased expression of the NR1 (WT, n=36, KO, n=37, F(1,69)=4.67, P=0.034) and D) NR2A subunits (n=43/genotype, failed normality, Rank Sum Test, T(43,43)=1610, P=0.025) relative to wild-type littermates, but E) no change in expression of the NR2B subunit (WT, n=39, KO, n=40). In VHIPP, there was no difference between Pde11a knockout mice vs. wild-type littermates in terms of F) NR1 (n=17/genotype), G) NR2A (WT, n=30, KO, n=31), nor H) NR2B (WT, n=18, KO, n=19). *vs WT, P=0.034-0.025. See Figure S7 for images of full blots. Brightness and contrast of blot images adjusted for graphical clarity. Data plotted as means ±SEMs. Images in panels A and B from Allen Institute for Brain Sciences http://connectivity.brain-map.org./3d-viewer.

Restoring PDE11A4 expression to VHIPP of adult Pde11a knockout mice is sufficient to reverse phenotypes.

The imaging study above suggests that vCA1 is key to the transient amnesia exhibited by Pde11a mutant mice. To determine if restoring PDE11A4 expression preferentially to vCA1 alone would be sufficient to rescue phenotypes exhibited by Pde11a knockout mice, we virally expressed emerald green fluorescent protein (eGFP) or eGFP-tagged Pde11a4 (Figure 7A) using coordinates that preferentially target CA1 in both dorsal hippocampus and VHIPP or VHIPP alone. Both constructs express well in the hippocampus (Figure 7B-C and S7H). Further, eGFP-PDE11A4 increased phosphorylation of the ribosomal protein S6 in VHIPP (Figure 7D) and attenuated expression of NR1 (Figure 7E)—but not NR2B (Figure 7F)—in the prefrontal cortex, suggesting engagement of relevant signal transduction cascades and circuits. Relative to eGFP-infected knockout mice, eGFP-Pde11a4-infected knockout mice showed improved STFP memory 24h after training (Figure 7G), impaired STFP memory 7 days after training (Figure 7H), and improved SOR memory 24 hours after training (Figure 7I). In contrast, restoration of PDE11A4 expression had no effect on NSOR 24h (Figure 7J-K) or 7d after training (Figure 7L). We did not assess Arc expression in virally-treated animals nor include an eGFP-treated wild-type group, which are limitations of the study. That said, behavioral performance of eGFP-Pde11a4-infected knockout mice (Figure 7G-L) appears to be comparable to that of unsurgerized Pde11a wild-type mice (e.g., Figure 1B-C), suggesting restoration of PDE11A4 completely reversed the effects of Pde11a deletion. Together, both viral and knockout studies suggest PDE11A4 regulates social but not non-social memories.

Figure 7. Restoration of PDE11A4 in vCA1 of adult Pde11a knockout mice is sufficient to reverse social memory phenotypes without altering non-social memory.

A) Schematic of the custom lentiviral transfer vector used to drive expression of either eGFP-Pde11a4 or eGFP alone (green star = site of construct insertion). B) Expression in dorsal (DHIPP) and ventral hippocampus (VHIPP) of Pde11a knockout mice was confirmed by Western blot. C) Immunofluorescence 2 months following injection shows eGFP-PDE11A4 appropriately traffics throughout dendrites of stratum radiatum (SR) in CA1 (also see Figure S7). D) Relative to eGFP alone, eGFP-PDE11A4 expression significantly increases phosphorylation of the ribosomal protein S6 at residues 235/236 in VHIPP of Pde11a knockout mice (n=4/virus, t(6)=2.74, P=0.034), suggesting engagement of relevant signal transduction cascades [8]. E) Restoring eGFP-PDE11A4 expression also attenuates NR1 expression in PFC of Pde11a knockout mice (+eGFP, n=11, +eGFP-PDE11A4, n=10, F(1,17)=5.06, P=0.038) without changing F) NR2B expression, suggesting engagement of relevant circuits. G) Control knockout mice (n=20 GFP-treated + 1 sham) showed no recent LTM for STFP as expected (t(19)=1.55, P=0.14); however, PDE11A4-infected Pde11a knockout mice (vCA1+dCA1, n=16; vCA1 only, n=11) did show recent LTM (vCA1+dCA1: t(14)=5.54, P<0.0001; vCA1-only: t(10)=2.11, P=0.031). H) Also as expected, control Pde11a knockout mice (n=13) regained memory 7 days after training (t(12)=2.82, P=0.008); whereas, PDE11A4-infected Pde11a knockout mice (vCA1+dCA1, n=12, vCA1-only, n=6) acted like PDE11A wild-type mice showing no remote LTM for STFP (vCA1+dCA1: t(11)=0.67, P=0.26; vCA1-only: t(5)=0.53, P=0.69). I) Surprisingly, control knockout mice (n=20) showed a significant SOR LTM 24 hours after training (t(20)=4.86, P<0.0001), suggesting surgery partially rescued the SOR deficit normally observed in unsurgerized knockout mice (e.g., Figure 1G). That said, expression of eGFP-PDE11A4 in vCA1+dCA1 (n=20) or vCA1 alone (n=12) produced preference ratios that were twice as strong as that measured in the control group (failed normality; H(2)=16.92, P=0.0002) and nearly identical to those observed in wild-type mice (e.g., Figure 1G), suggesting a full rescue. It is not yet clear why surgerized knockouts here show a significant SOR memory 24 hours after training when unsurgerized knockouts do not. This effect may be related to severing of some vital circuit upon insertion of the needle or exposure to the anesthesia, but is not related to GFP expression as mock-surgerized knockout mice show a similar weak memory (see Figure S7I). To verify that viral expression of PDE11A4 affected only those behaviors impacted by genetic deletion, we lastly tested mice on NSOR. As expected, there was no effect of virus on recent LTM for NSOR using either the J) 3-bead protocol or K) 2-bead protocol. L) There was also no effect of the virus on remote LTM for NSOR. M) Schematic of working hypothesis. Deletion of PDE11A4 relocates memories to the cortex ahead of schedule at the expense of prematurely erasing/silencing the hippocampal trace, which temporarily “misplaces” the memory because retrieval vectors are not similarly updated in an expedited manner. The green arrow pointing from the hippocampus (in blue) to the prefrontal cortex along with the emergence of green coloration in prefrontal cortex indicates systems consolidation within the cortex, while the red line drawn from prefrontal cortex towards hippocampus and red coloration of the ventral hippocampus indicates silencing/erasure. Timing of retrieval vector updating is based on lesion studies summarized elsewhere [1]). See Table S1 for one-sample t-tests, and Table S2 for other post hoc analyses. LTR—long terminal repeat (*=mutated), HIV—human immunodeficiency virus, PGKp—phosphoglycerate kinase 1 promoter, eGFP—emerald green fluorescent protein, WPRE—woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element, Amp-R—ampicillin resistance cassette, LM—lacunosum moleculare, SO—stratum oriens. Post hoc, #vs. GFP/control, P=0.034-0.0008; *significantly >0 (=memory), P≤0.03-0.0001. Data plotted as means ±SEMs.

DISCUSSION

Here, we show that remote LTM for social experiences can be decoupled from recent LTM when PDE11A4 is deleted from vCA1. Importantly, there is no need for additional reminders, retrievals, training sessions nor pharmacological manipulations to elicit the recovered/improved remote LTM that is observed in adolescent and adult Pde11a mutant mice (Figures 1-2, S2-3 and S5). Our findings build on previous studies showing equivalent or improved recent LTM in absence of short-term or intermediate memory, respectively [19, 20]. They also build on findings showing spontaneous recovery–but not improvement–of remote LTM following recent LTM deficits caused by selective/preferential loss of protein or norepinephrine synthesis in the hippocampus [10, 21]. The fact that protein synthesis inhibitors can cause transient amnesia for LTMs under select training conditions is quite interesting in the context of the present findings because Pde11a knockout mice exhibit reduced hippocampal expression of the protein synthesis biomarker phosphorylated-S6 [8]. Not only do these results identify a novel molecularly-defined population of cells regulating remote social LTMs (namely PDE11A4-expressing neurons in vCA1), they also illustrate the importance of assessing the effects of LTM manipulations well beyond a time point at which an initial memory deficit is noted.

Systems consolidation processes may differ between social and fear memories. It has been suggested that the processes underlying systems consolidation are the same for all episodic-like memory types [2]; however, our results here suggest this may not be the case. Studies of contextual fear conditioning show hippocampus-mediated “replay” of the recent memory engram to the cortex is required to permanently mature the cortical engram to the point of sustaining remote retrieval [3], suggesting you must have recent LTM in order to have remote LTM. Here, we show it is possible to exhibit enhanced remote LTM for social experiences in absence of any demonstrable recent LTM for those same events (Figure 1 and 7). Further, correlations of retrieval-induced immediate-early gene expression across hippocampal and cortical subregions suggests functional connectivity of these subregions is far stronger when retrieving a remote vs. recent contextual fear conditioning LTM [22]; however, we see the opposite pattern with retrieval of an STFP LTM (Figure 5). Finally, lesion studies suggest systems consolidation of contextual fear conditioning starts around 15 days post training, whereas, systems consolidation of STFP is complete 7-10 days after training [1]. Notably, although Pde11a knockout mice demonstrate impaired social memories 24 hours following training, they show intact contextual fear conditioning [9].

PDE11A4 molecularly defines an exceptionally discrete hippocampal circuit, connecting subiculum, CA1, and the adjacently connected amygdalohippocampal area, with greater expression in VHIPP than dorsal hippocampus (Figure 3A-B). We speculate that the decoupling of recent vs. remote LTM that is observed in Pde11a knockout mice is directly related to this unique expression pattern. For example, information stored in CA1, as compared to other hippocampal subfields, appears to more quickly and completely undergo systems consolidation in both humans and rodent studies [23, 24]. Further, both our imaging and rescue experiments suggest that it is the loss of PDE11A4 specifically from vCA1 that causes transient amnesia for social LTMs in mice, which is consistent with CA1 deficits associated with transient global amnesia in humans [25]. PDE11A4 is the only PDE whose expression in brain is restricted to the hippocampal formation [16]. As such, we may not expect the lost function of other PDEs to yield transient amnesia because cyclic nucleotide signaling would be modified in an entirely different circuit, both within and outside of the hippocampus. Indeed, inhibition of PDE2A, PDE5A, PDE9A, and PDE10A are all reported to improve recent social LTMs [26-29]. The characterization of other PDE knockout mice will be of strong interest to future studies—as will be revisiting other mutant mouse lines where recent LTM deficits have been noted but remote LTM never tested.

In addition to impacting overall levels of neuronal activity within systems consolidation-related brain regions, deletion of PDE11A changed the functional connectivity underlying recent vs. remote LTM retrieval (Figure 5). It should not be surprising that deletion of a hippocampus-specific gene could influence the activity and functional connectivity of extrahippocampal brain regions. CA1 projects not only to subiculum and entorhinal cortex, but also anterior cingulate, retrosplenial, orbitofrontal, and numerous other cortical regions (e.g., [30, 31]). Indeed, pharmacological inactivation of the hippocampus decreases Arc expression not only in the hippocampus but also in cortical regions to which the hippocampus projects (e.g., [32]). Further, electrical abnormalities within the hippocampus can interfere with storage of STFP memories within the cortex [33], which raises the interesting possibility that enhanced hippocampus-cortex communication could promote storage in the cortex.

While elements of a hippocampus-dependent memory are thought to be initially encoded simultaneously within both the hippocampus and cortex, only the hippocampal trace is sufficiently mature to support retrieval of a recent memory [3]. The standard systems consolidation model suggests that hippocampus-mediated “replay” of the memory to the cortex is required to permanently mature the cortical engram to the point of sustaining retrieval, at which time the hippocampal trace is erased/silenced [1, 3]. To reconcile our findings with that of the standard systems consolidation theory, we hypothesize that deletion of PDE11A triggers changes in hippocampus neuronal activity that mimic aspects of memory rehearsal, thus, expediting systems consolidation within the cortex at the expense of prematurely erasing/silencing the trace in the hippocampus (Figure 7M). For example, Pde11a deletion may increase cAMP-PKA signaling in noradrenergic circuits, which would promote the frequency and amplitude of sharp wave ripples [34]. Sharp wave ripples are high frequency oscillatory events thought to represent hippocampal replay of memories to the cortex during systems consolidation (e.g.,[35]). In this context, it is interesting to note that the loss of norepinephrine synthesis in the hippocampus results in transient amnesia of hippocampus-dependent memories (although not stronger remote LTM) [21]). Imaging of Arc mRNA does suggest that deletion of PDE11A4 alters functional connectivity between the hippocampus and systems consolidation-related cortical regions. For example, area 2 of anterior cingulate cortex (Cg2) tends to be uniquely functionally connected to other frontal cortical regions in Pde11a wild-type mice but hippocampal/parahippocampal regions in Pde11a knockout mice (Figure 5). We hypothesize that PDE11A deletion only mimics certain aspects of memory rehearsal because, of course, rehearsal usually leads to strengthening of both recent and remote LTM. While deletion of PDE11A may be sufficient to expedite systems consolidation, we believe it is not sufficient to update retrieval vectors in the way true memory rehearsal does. This would temporarily “misplace” the memory because the origin and destination of retrieval vectors change with time [3, 36] (Figure 7M). Indeed, such a temporary “blackout” is seen with normal memories as they transition from short-term to intermediate memory or intermediate to LTM—the so-called “Kamin effect” (c.f., [37]).

Moving beyond the standard theory of systems consolidation, alternative explanations may explain the transient amnesia that is observed following Pde11a deletion. For example, Pde11a deletion may produce transient amnesia by promoting schema formation in the cortex while activating forgetting pathways in the hippocampus. Information more quickly undergoes system consolidation when acquired in the context of a pre-existing framework of knowledge (i.e., a schema) [38]. Perhaps Pde11a deletion promotes the formation of schema in the prefrontal cortex as a consequence of upregulating NR1 and NR2A subunits (Figure 6; [39]). That said, there does not appear to be a systematic difference between animals who were tested on their first versus second STFP memory (Figure S2), which might argue against a role for PDE11A in schema formation. At the same time, Pde11a deletion may promote active forgetting pathways in the hippocampus. For example, Pde11a deletion would be expected to increase cAMP-PKA activity [9], which could increase phosphorylation of cofilin (e.g., [40]) and, thus, promote forgetting [41]. In addition, Pde11a deletion would be expected to increase cGMP [42] and reduce phosphorylation of CamKIIα [16], both of which could lead to synaptic depotentiation or a failure to maintain long-term changes in synaptic plasticity (c.f., [43]).

Our working hypothesis is based on the premise that the hippocampus/hippocampal formation (i.e., hippocampus plus subiculum) is required for the initial formation and/or system consolidation of social memories. This premise is based on a large number of studies using a variety of approaches (i.e., lesions, transcription/translation blockade, perturbed neurotransmission, etc.) (e.g., [1, 4-7, 13, 44-77]). That said, contrary reports have been published [75-80], and one study suggests that hippocampal formation lesions prevent the transition from recent to remote LTM due to the generation of aberrant electrical activity within the hippocampus that interferes ongoing system consolidation elsewhere in the brain [33]. If social memories do not require the hippocampus, we can entertain the hypothesis that PDE11A4 deletion produces transient amnesia by generating pathological activity patterns in the hippocampus that then interfere with processing in cortical circuits. Looking to our Arc data, there is a suggestion of altered neuronal activity in vCA1 of knockouts during the retrieval of a recent LTM; however, there was no corresponding change in cortical Arc expression and differential vCA1 expression was not seen during the retrieval of the remote LTM. Further, if deletion of PDE11A4 causes aberrant activity in the hippocampus similar to that explored by Thapa et al. [33], we might then expect to see an impairment in both recent and remote long-term social memories; however, Pde11a knockouts mice show enhanced remote memory.

Perhaps it is possible that recent long-term social memories are stored in one cortical region but remote longterm social memories undergo system consolidation in a separate cortical region via synaptic reentry reinforcement (c.f., [10]). If so, then perhaps the ventral hippocampal formation normally suppresses system consolidation (c.f. [81]) or promotes decay of remote memories within that secondary cortical region (c.f., [82]), and PDE11A4 deletion prevents this suppression/decay. This would be consistent with Pde11a knockout mice exhibiting enhanced remote memory. That said, several studies discussed above argue against such a role for the hippocampus in social memory. Hippocampus +/− subiculum lesions performed prior to training and/or 1-2 days immediately following acquisition resulted in weaker, not stronger, remote long-term social memories [44, 45, 48, 75-77, 83]. One may suggest the “aberrant electrical activity” proposed by Thapa et al. [33] interferes with the ability to visualize the removal of hippocampal-mediated suppression/decay. However, when Thapa et al. lesioned while suppressing that activity, memory at 9 days was only equivalent to controls, it was not improved [33]. Taken together, our data in combination with the literature to not appear to readily conform to the suggestion that the hippocampal formation is not required for the storage of social LTMs.

Parsimoniously, our findings appear to support the theory that the hippocampal formation—and PDE11A4 therein—is critical to the long-term storage of social memories. Given the location and signaling pathway involved here, our findings may have particular relevance for the abnormally strong remote LTMs found in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder and/or the cognitive deficits observed with aging (because PDE11A4 expression increases with age [16] and social associative memories are particularly vulnerable to age-related cognitive decline [84, 85]), temporal lobe epilepsy (i.e., transient amnesia, accelerated long-term forgetting, etc. [86]), or transient global amnesia [25].

STAR METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY.

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Dr. Michy Kelly (Michy.Kelly@uscmed.sc.edu). Breeding pairs from the Pde11a mutant mouse line can be made available; however, a license must first be obtained from Deltagen and a material transfer agreement signed with the University of South Carolina. Plasmids used in these studies can be made available upon request following the signing of a material transfer agreement with the University of South Carolina. New batches of lentivirus can be generated by the Viral Vector Lab of the University of South Carolina for a fee following the signing of a material transfer agreement with the University of South Carolina.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Pde11a knockout mice were originally developed by Deltagen (San Mateo, CA), and are maintained on a mixed C57BL/6J (86.6%)-C57BL/6N (12.4%)-129S6 (1%) background (background confirmed by Transnetyx genetic monitoring service, Cordova TN), as previously described [8, 9, 87, 88]. All isoforms of Pde11a are deleted by virtue of targeting the catalytic domain (note: PDE11A4 is the only isoform expressed in brain [89]). Pde11a mice were bred onsite in heterozygous x heterozygous trio matings (2 females/1male), with same-sex wild-type, heterozygous, and knockout littermates (defined as any mice born at the same time to either dam) weaned together in groups of 3-5 mice, with the exception of knockout mice that were designated for surgery experiments that were housed with other knockout mice and 1 heterozygous mice to act as a demonstrator (see STFP protocol below). A given litter typically provides 1 mouse/genotype, but on occasion may provide more than 1 mouse/genotype if numbers can be roughly balanced by another litter. Littermates that are weaned together are then tested in the same experiment. Pde11a heterozygous mice were not included in select behavioral studies due to a lack of availability at the time of the study (e.g., needing to set up a large number of heterozygous x heterozygous matings), and heterozygous mice were not included in the Arc studies as we can only accommodate 4 brains in a sectioning block (see Figure 6S). The lack of heterozygous mice in these select experiments is acknowledged as a limitation of the study. Of further note, Pde11a heterozygous mice show a 50% reduction in PDE11A4 mRNA but an 80% reduction in PDE11A4 protein in both ventral and dorsal hippocampus [87]. Therefore, we might not expect to observe a truly intermediate phenotype in the Pde11a heterozygous mice. Adult mice were tested between 2-12 months of age and adolescent mice were tested between postnatal day 28 and 42, for consistency with our previous report [8]. Note, only studies in Figure 2 used adolescent mice; all other experiments described herein employed adult mice. There is essentially no concern of litter effects as 1) experiments were repeated in multiple cohorts and 2) any given litter typically contributes n=1-2 mice/genotype and, at most, parents contribute 2 litters to a cohort (i.e., a total of 2-4 mice/genotype). Animals are housed on a 12:12 light:dark cycle and generally allowed ad lib access to food and water (exception applies when training/testing for social transmission of food preference—see below). As previously described [8], some cohorts of mice were tested in multiple assays (social odor recognition then non-social odor recognition then social transmission of food preference with at least 1 week between tests), whereas, some cohorts were tested in only 1 assay. There was no apparent effect of testing history. See Figure Legends for experimental n’s (approximately equal numbers of males and females used). In all experiments, genotypes were counterbalanced across technical variables (e.g., bead position, spice combination and placement, position on gel, etc.). Experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Pub 85-23, revised 1996) and were fully approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of South Carolina.

METHODS DETAILS

Social transmission of food preference (STFP) was conducted as previously described [8] (Figure S1A). Briefly, access to food was restricted to 1 hour/day for 2 days and then a designated “demonstrator” mouse (a wild-type or heterozygous) was fed powdered food laced with 1 of 2 household spices (e.g., 1% cardamom vs. 1% mint, 1.5% thyme vs. 4.5% turmeric, 4% marjoram vs. 1% cumin, or 2% basil vs. 2% ginger, 5% orange vs. 0.5% anise, or 2% basil vs. 1.5% thyme). The “observer” subject mice then interact with the demonstrator and make an association between the non-social odor (i.e., a household spice) and pheromones in the demonstrator’s breath [90, 91]. To be clear, simply smelling a food laced with a given spice is not sufficient to produce a food preference, there must be an association made between the odor of that spiced food and pheromones in the saliva of a live rodent [90, 91]. The memory of this association becomes a safety signal that lets the observer know a food is safe to eat. Therefore, when presented with 2 differently spiced foods at testing (15 minutes, 24 hours, or 7 days later, Figure S1A), observers that formed and retrieved the memory will eat more of the food laced with the spice eaten by their demonstrator vs. the food that is laced with a novel spice. Within each experiment, assignment of a given spice as trained vs. novel is counterbalanced across subjects. A given STFP memory—the memory that a given odor indicates a food is safe to eat based on its association with a cage mate’s breath—can only be tested once because testing changes the nature of the memory from one of the odor association to one of having actually eaten the food. That said, we were able to test multiple retrieval intervals in the same mice by training and then testing select cohorts on a second set of odors (see Figure S2 for further details). Therefore, some cohorts underwent training with different spice combinations in order to test the same mice on more than 1 retrieval interval (STM, 15 minutes after; recent LTM, 24 hours after training; remote LTM, 7 days after training), with other cohorts tested only once (Figure S2). 7 days was chosen as the remote LTM time point based on lesion studies showing STFP memories become independent of the hippocampus 5-10 days after training (c.f.,[1]). The spice combinations used were counterbalanced across cohorts as were the order of the tests. For example, one cohort could be tested at 24hr with basil vs. ginger and 7d with cardamom vs. mint while another cohort could be tested on STM with basil vs. ginger and 24hr with cardamom vs. mint. The food jars were weighed before and after the test to measure the total amount of food eaten. An experimenter, blind to genotype and food status, manually scored the time spent eating each food for 1 min every 10 min in all experiments except the “7d Arc experiment” (which also included 2 pairs of wild-type/knockout littermates tested at 24 hours, see Figure S2) and those involving the surgerized mice due to lack of available personnel at the time of the study. STFP memory is operationally defined as subjects demonstrating stronger preference for the trained vs the novel food. Mice had to eat at least 0.25 gm of food total and have been observed eating >5 seconds to be included in analyses. Because there is significant variability among mice within a group in terms of the total amount of food eaten or the total time spent investigating the odorized beads, data are normalized. To normalize data, a preference ratio was calculated = (novel-familiar)/(novel+familiar) for statistical analysis [20]. Note, this stands in contrast to our previous report in which we normalized data by reporting the amount of each food eaten or the amount of time spent eating each food as a percent of the total amount of food or time [8]. To enable direct comparison of our previous work with our current findings, data from Figure 1 is also shown graphed as per our previous method (Figure S3).

Odor recognition was conducted as previously described [8] (Figure S1B). Briefly, mice were habituated to 1” round wooden beads (Woodworks) placed in the home cage for 7-14 days. These beads become saturated with the scent of the subjects (home-cage odor). Training consisted of 3 trials. For the 1st trial, mice were presented with 3 of their own home-cage beads for a 3-min habituation trial. Then, for the 2nd and 3rd 3-minute trial (5 minute inter-trial interval), mice were presented with 2 of their own home-cage beads and 1 scented bead. In the case of social odor recognition, the scented bead came from the cage of another mouse strain (same-sex C57BL/6J Jax #000664, BALB/cJ Jax #000651, or 129S6/ SvEv Taconic #129SVE). In the case of non-social odor recognition, the scented bead came from a bag of bedding that was never exposed to a mouse but rather was saturated with a household spice (basil, ginger, or thyme). Beads from different mouse strains are used as social odor donors, as opposed to beads from other mice within the colony, because we previously found that it is possible for individual mice from the same inbred strain to not smell different from each other [8]. Memory was tested 1 hour (short-term memory, STM), 24 hours (recent long-term memory, recent LTM) or 7 days later (remote LTM). 7 days was chosen as the remote LTM time point based on lesion studies showing social memories become independent of the hippocampus 5-10 days after training (c.f.,[1]). Testing for SOR consisted of a single 2-min trial in which the mouse was presented 1 home-cage bead, 1 bead from the strain experienced during training (i.e., familiar odor), and 1 bead from a 2nd novel mouse strain (i.e., novel odor). For NSOR, testing similarly consisted of a single 2-min trial in which the mouse was presented 1 bead from the spice experienced during training (i.e., familiar odor) and 1 bead from a 2nd novel spice (i.e., novel odor), with a home cage bead included in some cohorts (to mirror testing conditions of SOR) but not others (to better mirror the 2-spice testing conditions of STFP, see below). Assignment of a strain/spice as ‘familiar’ or ‘novel’ is varied across sets of littermates, to ensure memory phenotypes are not specific for 1 particular odor. The amount of time, in seconds, that the mice spent investigating the beads was manually recorded by an experimenter blind to genotype and novelty of the beads. Mice must spend at least 3 seconds investigating the beads for inclusion (mice not reaching threshold/total number of mice tested: Figure 1L, 1/54; Figure 2E 4/41; Figure 2F, 11/57; Figure 2G, 1/60). Social odor recognition memory is operationally defined as subjects spending significantly more time exploring the novel vs familiar scent. Because there is significant variability among mice within a group in terms of the total time spent investigating the odorized beads, data are normalized. This variability is not related genotype, although it is related to sex in the case of time spent investigating the social—but not the non-social—odor beads (Figure S4). To normalize data, a preference ratio was calculated = (novel-familiar)/(novel+familiar) for statistical analysis [20]. Note, this stands in contrast to our previous report in which we normalized data by reporting the time spent investigating each bead as a percent of the total time exploring all beads [8]. To enable direct comparison of our previous work with our current findings, data from Figure 1 is also shown graphed as per our previous method (Figure S3).

Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

Biochemistry and molecular biology experiments were conducted as previously described [8, 9, 15, 16, 92] (See Figure S6 for workflow). Animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. For the Arc study, mice were sacrificed from the home cage, to identify any basal effects of genotype on Arc expression, or 45 minutes into an STFP memory test 24 hour or 7 days following training. Frozen tissue was stored at −80° C until processing. For in situ hybridization, brains were embedded and cryosectioned in blocks of 4, with each block/slide including a wild-type-home cage, knockout-home cage, wild-type-tested, and knockout-tested brain. Autoradiographic in situ hybridization for Arc mRNA was conducted using the following antisense oligonucleotide probe: GCAGCTTCAGGAGAAGAGAGGATGGTGCTGGTGCTGG. Specificity was confirmed with a sense probe. Relative optical densities (r.o.d.’s) for brain regions (defined as per [93]) were quantified using the MCID system by an experimenter blind to genotype and training condition. Arc was preferred here over other immediate-early genes because 1) it is induced by plasticity-related increases in cGMP and cAMP [94, 95] — both of which are PDE11A4 substrates, 2) its induction has been more closely tied to memory-related processing than other IEGs (e.g., [96-98]) and 3) we have a long history of using this technique for mapping learning/memory-related neuronal activity (e.g., [92, 99, 100]). Our analyses focused on brain regions known to play a role in systems consolidation of STFP or other HIPP-dependent tasks, namely the PDE11A4-expressing hippocampal subfields (i.e., CA1 and subiculum), parasubiculum [101], anterior cingulate cortex [13, 102-110], frontal association cortex as a subsection of medial prefrontal cortex [3, 108, 111-113], and the superficial layers of medial entorhinal cortex [101, 112, 114, 115]. Raw optical densities and correlations of those densities were analyzed (see Figure S6 for visualization of work flow), with raw r and P values from correlations reported in Data S1 and means and SEMs for all figures reported in Data S2.

For Western blot experiments, mice were sacrificed from the home cage, individual brain regions were dissected and immediately cryopreserved at −80. Freshly-frozen tissue was sonicated in boiling lysis buffer (50 mM NaF/1% SDS), and 33 μg total protein for each sample was separated by gel electrophoresis using Invitrogen 4-12% Bis-Tris gels (Life technologies). Following transfer, nitrocellulose membranes were probed with primary antibodies (PDE11A4, “#1” custom antibody from Aves, 1:20,000 [8]; GFP, sc8334 from Santa Cruz, 1:2000; S6, #2217S from Cell Signaling, 1:200; pS6-235/236, #4856S from Cell Signaling, 1:2500; pS6-240/244 #4838S from Cell Signaling, 1:500; NR1, #05-432 from Upstate, 1:5000; NR2A, #612286 from BD Transduction, 1:2500; NR2B, sc-1469 from Santa Cruz, 1:1000; actin, Sigma #A2066, 1:10,000; and a species-appropriate HRP-tagged secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch, 1:10,000. All antibodies except S6 were developed using Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermoscientific; #34078); whereas, S6 was developed using Westernsure Premium Chemiluminescent Substrate (Licor; #926-95000). Multiple film exposures were taken to ensure data were collected within the linear range. Westerns were quantified using Image J (NIH) by an experimenter blind to genotype. Images of exemplar full blots for each antibody are shown in Figure S7A-G.

Surgery.

Stereotaxic surgery was performed using the NeuroStar motorized stereotaxic and drill and injection robot (Tubingen, Germany). Mice were anesthetized using inhaled isoflurance (3% induction, 1-1.5% maintenance). Upon verification of a lack of reflexes, the scalp was shaved, swabbed with betadine, and then cut open. The skull was swabbed with sterile saline and allowed to air dry. Small holes were drilled using the robotic drill as per the following coordinates relative to Bregma (dCA1 AP, −1.7, dCA1 ML, +/− 1.6, vCA1 AP, − 3.5, vCA1 ML, +/−3.0). 30 seconds after the Hamilton syringe needle (custom needle #7804-04: 26s gauge, 1” length, 25 degree bevel) reached the following depths relative to Bregma (dCA1 DV, − 1.3, vCA1 DV, −4.4), 0.5 μl of lentivirus (titers: eGFP-only, ~10×106 TU/μl; eGFP-PDE11A4 7.4×106, see details below) suspended in 0.2M sucrose/42 mM NaCl/0.84 mM KCl/2.5 mM Na2HPO4/0.46 mM KH2PO4/0.35 mM EDTA was infused using the injection robot at an infusion rate of 0.167 μl/minute. 2 minutes after completion of the delivery, the needle was removed using the lowest speed setting. The scalp was closed using glutures and the animal was allowed to recover for at least 2 weeks prior to behavioral testing. Viral expression did not appear to trigger gross morphological damage/toxicity in cells (either in vivo in the brain or in vitro in COS-1 cells) and virally-injected animals appeared normal and healthy following recovery from the surgery.

A lentivirus was used to restore expression of PDE11A4, as opposed to an adeno-associated virus-due to the large size of the gene (over 3kB). The lentiviruses use a custom replicant-deficient backbone created by the Viral Vector Core of the University of South Carolina. This backbone lacks the HIV envelope protein, the packaging sequence, as well as the essential rev gene, and the second long terminal repeat (LTR) is truncated. To generate an infectious lentivirus, HEK293T cells are transfected with 4 plasmids: 1) the viral transfer vector containing either eGFP or eGFP-tagged PDE11A4 [88], 2) a plasmid containing the essential rev gene, 3) a plasmid containing the vesicular stomatitis virus envelope gene, and 4) a transfer vector containing a complete LTR and a short viral sequence containing the packaging signal. The transducing unit was determined by realtime PCR using the genomic DNA of the infected cells as a template.

The phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK) promoter is used to drive expression of emerald green fluorescent protein (eGFP) or an eGFP-tagged PDE11A4 [88]. Although PGK is a ubiquitous promoter, in our experience (and those of our colleagues using the same custom SPW lentiviral backbone) it very much preferentially infects neurons--particularly CA1 neurons as opposed to subiculum neurons—for reasons that are not well understood. The catalytic activity of the GFP-tagged PDE11A4 was verified in COS-1 cells (cAMP levels (fold GFP): GFP-only 1.0 ±0.06 vs GFP-PDE11A4 0.57 ±0.08, t (28)=4.29, P<0.001, cGMP levels (fold GFP): GFP-only 1.0 ±0.08 vs GFP-PDE11A4 0.64 ±0.1, t (20)=2.87, P=0.009, measured using Cayman Chemical ELISA kits (Ann Arbor, MI) as previously described [29]). Viral expression was verified in each animal either by Western blot or sectioning and direct visualization of the GFP signal with a wide-field fluorescent microscope. The control group included all mice treated with the GFP-only virus as well as 1 mouse treated with the GFP-PDE11A4 virus that failed to express the recombinant protein (i.e., a sham control).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Experimental n’s for each group and statistics are noted in each Figure legend (note: approximately equal numbers of male and female subjects were used throughout, except in the case of the vCA1 surgery group that was mostly female). Statistical analyses were conducted using Sigmaplot 11.0, Statistica 9.0, or R. When data passed normality (Shapiro-Wilk) and equal variance (Levene’s mean test), data were analyzed by parametric statistics. For analysis of multiple groups/factors, ANOVA (F) or repeated measures ANOVA (F) was used, as appropriate, followed by Least-significant Difference Tests (LSD, only for post hoc analyses of difference scores; e.g., [20, 26, 27, 116, 117]) or Student-Newman Keuls Method (for all other analyses, per our previous work, e.g., [8, 15]). Although LSD tests are generally considered too liberal/weak, protected LSD post hoc tests (i.e, conducted only following an ANOVA with P<0.05 using the pooled variance) actually perfectly control family wise error rates in the special condition of analyzing 3 groups, even when n’s are not balanced. We have applied these post hoc tests to analyses including 3 groups (e.g., wild-type, heterozygous, knockout) only following a significant overall ANOVA; thus, correction of the post hoc P-values reported herein for LSD tests is not warranted in this special case. That said, Benjamini-Hochberg false-detection rate (FDR) [118] corrected P-values are shown in Table S2. It is also largely argued that Student Newman Keuls post hoc tests are similarly protected by an overall ANOVA with P<0.05 and some correction for multiple comparisons is already built into their formulation. That said, again, FDR-corrected P-values are shown in Table S2 for analyses where differences between genotypes are noted. To compare 2 groups, Student’s 2-tailed t-test (t) was used. One-sample t-tests were used to compare preference ratios to 0, and results are listed in Table S1 with raw and FDR-corrected P-values. Where data failed normality or equal variance, the nature of the failure was noted and, instead, a Mann Whitney Rank Sum test (U), Wilcoxon Signed Rank Sum test (Z) or Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA on Ranks (H), the latter followed by a Dunn’s post hoc test (listed in Table S2). Behavioral data were analyzed for effect of genotype, behavioral parameter (e.g., bead, food, etc), and sex for experiments with at least 6/sex/genotype [8, 9, 16]). Western blot data were similarly analyzed for effect of genotype and sex, with the exception of the pS6/S6 data that included too few subjects for an analysis of sex. Arc data were analyzed for effect of group with repeated measures by block (see Figure S6), but again sex was not included as a factor due to limited n. P-values resulting from these Arc data analyses (i.e., each regional RM ANOVA) were corrected for multiple comparisons by applying an FDR. Arc expression data were also analyzed by Pearson Product Moment Correlations (r) to assess the functional connectivity of brain regions. To be clear, the term “functional connectivity” does not imply cause and effect but, rather, allows for the fact that correlations can arise from remote neurophysiological events [14]. Correlational analyses of activity-regulated immediate-early gene expression have been used by us [15] and others [13, 119-126] to assess functional connectivity in rodents. To determine if genotype impacted the overall connectivity of a given brain region, the absolute value of each r score was z transformed and then these transformed scores for each brain region were compared between genotypes via paired t-test or Wilcoxon Signed Rank test if normality failed [13]. Note, however, it is the absolute strength of the untransformed r score (|r|) that is represented in graph form [13]. Previous reports employing this technique did not correct for multiple comparisons (e.g., [13]); therefore, we have reported both the raw P-values (to enable direct comparison of results between studies) and FDR-corrected P-values (see Figure 5 and Data S1). Statistical outliers (data points above or below 2 standard deviations from the mean; see Table S2 for enumeration of outliers/group) were removed from analyses, as previously described [15, 16, 127]. Significance was determined as P≤ 0.05 and data are plotted as means ±SEMs, which are listed in Data S2. For the most part, data were collapsed across sexes for sake of clarity because the effect of genotype did not differ as a function of sex in any experiment (see exception in Figures S4).

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

No code was generated during this study. Data for Figures 3-4 are available at Mendeley Data v2http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/4zwsgtk4m9.2DOI and data for Figure 5 is posted here in Data S1. Means and SEMs are posted here in Data S2; however, raw data sets other than those mentioned above are not posted but are available upon request.

Supplementary Material

Data S1. Pearson Product Moment Correlation coefficients (r) correlating Arc staining between brain regions in home cage (HC) mice or mice tested 24 hours or 7 days after training on social transmission of food preference. Related to Figure 5 and STAR Methods. vCA1--ventral CA1; vSub--ventral subiculum; dCA1--dorsal CA1; dSub--dorsal subiculum; PaS--parasubiculum; s-Ment--superficial layer medial entorhinal cortex; d-Ment--deep layer medial entorhinal cortex; FrA--frontal association cortex; Cg1--cingulate 1; Cg2--cingulate 2; V1--primary visual cortex; M2--motor cortex; WT-Pde11a WT-mice; KO-Pde11a knockout mice. Raw and false rate detection (FDR)-corrected P-values shown.

Data S2. Enumeration of mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) for data shown in graph form. Related to STAR Methods.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Chicken polyclonal anti-PDE11A | Aves [9] | Custom |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP | Santa Cruz | Cat#: sc8334; RRID:AB_641123 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-S6 | Cell Signaling | Cat#: 2217S; RRID:AB_331355 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-pS6235/236 | Cell Signaling | Cat#: 4856S; RRID:AB_2181037 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-pS6240/244 | Cell Signaling | Cat#: 4838S; RRID:AB_659977 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-NR1 | Upstate (Millipore) | Cat#: 05–432; RRID:AB_390129 |

| Mouse monoclonal anit-NR2A | BD Transduction | Cat#: 612286; RRID:AB_399603 |

| Goat polyclonal anti-NR2B | Santa Cruz | Cat#: sc-1469; RRID:AB_670229 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Actin | Sigma- Aldrich | Cat#: A2066; RRID:AB_476693 |

| Peroxidase AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Goat IgG (H+L) | Jackson Immunoresearch | Cat#: 705–035-147; RRID:AB_2313587 |

| Peroxidase AffiniPure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) | Jackson Immunoresearch | Cat#: 115–035-146; RRID:AB_2307392 |

| Peroxidase AffiniPure Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) | Jackson Immunoresearch | Cat#: 111–035-144; RRID:AB_2307391 |

| Cy™3 AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Chicken IgY (IgG) (H+L) | Jackson Immunoresearch | Cat#: 703–165-155; RRID:AB_2340363 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Lentivirus: SPW-eGFP | Viral Vector Core, University of South Carolina [90] | Custom |

| Lentivirus: SPW-eGFP-tagged PDE11A4 | Viral Vector Core, University of South Carolina [90] | Custom |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate | Thermoscientific; | Cat# 34078 |

| Westernsure Premium Chemiluminescent Substrate | Licor | Cat# #926–95000 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Cayman Chemical cAMP ELISA kit | Cayman Chemical Company | Cat# 581001 |

| Cayman Chemical cGMP ELISA kit | Cayman Chemical Company | Cat# 581021 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Analyzed Data | Mendeley Data | http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/4zwsgtk4m9.2DOI |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Cell Line: HEK293T | ATCC [90] | ATCC CRL-11268 |

| Cell Line: COS-1 | ATCC [90] | ATCC CRL-1650 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: Pde11a−/− (C57BL/6J-C57BL/6N-129S6/SvEvTac-Pde11a) | Deltagen [9, 10, 89, 90] | N/A |

| Mouse: C57BL/6J | The Jackson Laboratory/ In-house | Cat# 000664 |

| Mouse: BALB/cJ | The Jackson Laboratory/ In-house | Cat# 000651 |

| Mouse: 129S6/ SvEv | Taconic/ In-house | Cat# 129SVE |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| antisense probe: Arc: GCAGCTTCAGGAGAAGAGAGGATGGTGCTGGTGCTGG |

[24–26] | NM_018790.3 |

| antisense probe: Pde11a: CCACCAGTTCCTGTTTTCCTTTTCGCATCAAGTAATC |

[10,69,91] | NM_001081033.1 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| ImageJ | National Institute of Health (NIH) | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

| Sigmaplot 11.1 | Systat Software | N/A |

| Statistica 9.0 | Tibco | N/A |

| R-Project | R Foundation for Statistical Computing | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| Other | ||

| Invitrogen NuPAGE Novex 4–12% Bis-Tris | LifeTechnologies | Cat# NP0322BOX |

| Nitrocellulose Blotting Membranes | GE Helathcare Life Sciences | Cat# 10600008 |

| Neurostar Stereotax/Drill and Injection Robot | NeuroStar | https://robot-stereotaxic.com/drill-injection-robot/ |

| Hamilton Syringe | Hamilton | Cat #7804–04 (26s gauge, 1” length, 25 degree bevel) |

| 1” Wooden Beads | Woodworks Ltd. | Cat# RB1000 |

| 2-oz glass jar | Fisher Scientific | Cat# 02–911-773 |

Highlights.

Pde11a KO mice show no social memory at 24 hours yet stronger social memory at 7 days

This transient amnesia correlates with alterations in functional connectivity and NR1

Restoration of PDE11A to ventral CA1 is sufficient to reverse phenotypes

Long-term memory is not linear; remote memory can be decoupled from recent

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

The authors would like to Ms. Shweta Hegde for technical support and Drs. Steven Wilson and Seungjin Shen and the USC Viral Vector Laboratory for generation of the lentiviruses. Research supported by a Research Starter Grant in Pharmacology & Toxicology from the PhRMA Foundation, an ASPIRE award from the Office of the Vice President for Research from the University of South Carolina, a Research Development Fund Award from the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, 1R01MH101130 from NIMH, 1R01AG061200 from NIA, and a NARSAD Young Investigator Award from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (all awards to MPK) as well as a Magellan Scholar Award and SURF fellowship form the Office of the Vice President for Research and the Honors College of the University of South Carolina (to JK).

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS: The authors declare no competing interests

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Frankland PW, and Bontempi B (2005). The organization of recent and remote memories. Nat Rev Neurosci 6, 119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tonegawa S, Morrissey MD, and Kitamura T (2018). The role of engram cells in the systems consolidation of memory. Nat Rev Neurosci 19, 485–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitamura T, Ogawa SK, Roy DS, Okuyama T, Morrissey MD, Smith LM, Redondo RL, and Tonegawa S (2017). Engrams and circuits crucial for systems consolidation of a memory. Science 356, 73–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tseng KY, Chambers RA, and Lipska BK (2009). The neonatal ventral hippocampal lesion as a heuristic neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia. Behav Brain Res 204, 295–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kogan JH, Frankland PW, and Silva AJ (2000). Long-term memory underlying hippocampus-dependent social recognition in mice. Hippocampus 10, 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brightwell JJ, Smith CA, Countryman RA, Neve RL, and Colombo PJ (2005). Hippocampal overexpression of mutant creb blocks long-term, but not short-term memory for a socially transmitted food preference. Learn Mem 12, 12–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okuyama T, Kitamura T, Roy DS, Itohara S, and Tonegawa S (2016). Ventral CA1 neurons store social memory. Science 353, 1536–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hegde S, Capell WR, Ibrahim BA, Klett J, Patel NS, Sougiannis AT, and Kelly MP (2016). Phosphodiesterase 11A (PDE11A), Enriched in Ventral Hippocampus Neurons, is Required for Consolidation of Social but not Nonsocial Memories in Mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 41, 2920–2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly MP, Logue SF, Brennan J, Day JP, Lakkaraju S, Jiang L, Zhong X, Tam M, Sukoff Rizzo SJ, Platt BJ, et al. (2010). Phosphodiesterase 11A in brain is enriched in ventral hippocampus and deletion causes psychiatric disease-related phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 8457–8462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amaral OB, Osan R, Roesler R, and Tort AB (2008). A synaptic reinforcement-based model for transient amnesia following disruptions of memory consolidation and reconsolidation. Hippocampus 18, 584–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machado A, Rodrigues M, Ribeiro M, Cerqueira J, and Soares-Fernandes J (2010). Tadalafil-induced transient global amnesia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 22, 352t e328–352 e328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schiefer J, and Sparing R (2005). Transient global amnesia after intake of tadalafil, a PDE-5 inhibitor: a possible association? Int J Impot Res 17, 383–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanimizu T, Kenney JW, Okano E, Kadoma K, Frankland PW, and Kida S (2017). Functional Connectivity of Multiple Brain Regions Required for the Consolidation of Social Recognition Memory. J Neurosci 37, 4103–4116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friston KJ (2011). Functional and effective connectivity: a review. Brain Connect 1, 13–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pathak G, Ibrahim BA, McCarthy SA, Baker K, and Kelly MP (2015). Amphetamine sensitization in mice is sufficient to produce both manic- and depressive-related behaviors as well as changes in the functional connectivity of corticolimbic structures. Neuropharmacology 95, 434–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly MP, Adamowicz W, Bove S, Hartman AJ, Mariga A, Pathak G, Reinhart V, Romegialli A, and Kleiman RJ (2014). Select 3’,5’-cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases exhibit altered expression in the aged rodent brain. Cell Signal 26, 383–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]