Abstract

Background.

In the United States, alcoholic liver disease (ALD) has recently become the leading indication for liver transplantation.

Methods.

Using the United Network for Organ Sharing registry, we examined temporal trends in adult liver transplant waitlist (WL) registrants and recipients with chronic liver disease (CLD) due to ALD from 2007 to 2016.

Results.

From 2007 to 2016, ALD accounted for 20.4% (18399) of all CLD WL additions. The age-standardized ALD WL addition rate was 0.459 per 100000 US population in 2007; nearly doubled to 0.872 per 100000 US population in 2016 and increased with an average annual percent change of 47.56% (95% confidence interval, 30.33% to 64.72%).The ALD WL addition rate increased over twofold among young (18–39 years) and middle-aged (40–59 years) adults during the study period. Young adult ALD WL additions presented with a higher severity of liver disease including Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score compared to middle aged and older adults (≥60 years). The number of annual ALD WL deaths readily rose from 2014 to 2016, despite an overall annual decline in all CLD WL deaths. Severe hepatic encephalopathy, low body mass index (<18.5) and diabetes mellitus were significant predictors for 1-year WL mortality.

Conclusions.

Alcoholic liver disease-related WL registrations and liver transplantation have increased over the past decade with a disproportionate increase in young and middle-aged adults. These subpopulations within the ALD cohort need to be evaluated in future studies to improve our understanding of factors associated with these alarming trends.

Currently, alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is the leading indication for liver transplantation (LT) in the United States.1 Over the past 2 decades, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has been the leading indication for LT in the United States.2,3 The approval of efficacious second-generation direct-acting antiviral (DAA) agents in late 2013 has reduced the burden of HCV-related end-stage liver disease as reflected by a significant decline in liver transplant waitlist (WL) registrations and associated WL mortality in patients with the primary diagnosis of HCV.4 Despite this downtrend in HCV-related WL registrations, the number of annual WL registrants awaiting LT has continued to increase, largely explained by the recent rise in ALD WL registrants.1 Moreover, the number of annual WL registrants without ALD has remained unchanged due to a rise among nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) WL registrants negating the decline in HCV-related WL registrants.1 In 2016, both ALD and NASH surpassed HCV as the first and second leading indications for LT in the United States, respectively.1 ALD remains an orphan liver disease in the United States in terms of primary and secondary prevention and effective therapeutic options with the majority of focus on viral hepatitis and NASH. In this study, we aim to delineate the demographic characteristics associated with the rise in end-stage liver disease in the setting of ALD.

The recent surge in ALD-related LT in the United States is not unprecedented. National data from 2001 to 2013 have demonstrated that the prevalence of alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and alcohol use disorder were on the rise among both males and females across all age groups in the United States.5 These data forecasted an increase in alcohol-related comorbidities with rise in associated healthcare costs and expenditure.6 Among all chronic liver disease (CLD)-related deaths in the United States, more than 40% are attributed to ALD in both men and women.7 Age-specific mortality trends in CLD have demonstrated that young and middle-aged adults, ages 25 to 44 years, have been most affected, with over 70% of CLD-related deaths within this age group due to ALD.7 With the prevalence of ALD continuing to rise, we examined temporal trends in ALD-related age- and sex-specific changes in WL registrations and LT, and the impact of ALD-related LT in the United States.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source

Our study utilized national data on all liver transplant WL registrants and LT recipients in the United States using the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and United Network for Organ Sharing (OPTN/UNOS) registry. This study was exempt from Institutional Review Board at our institution.

Study Population

We performed a retrospective study analyzing adult (≥18 years) liver transplant WL registrants and recipients with CLD due to ALD over a 10-year time period from 2007 to 2016. The etiology of CLD leading to WL registration and LT was determined based on primary and secondary diagnosis codes in the OPTN/UNOS registry for alcoholic cirrhosis. ALD registrants with a concomitant primary or secondary diagnosis code for viral hepatitis including chronic hepatitis B virus infection and HCV or NASH were considered as CLD due to hepatitis B virus, HCV or NASH, and therefore were excluded from the primary ALD cohort.8 Due to variability in defining NASH in CLD registrants with cryptogenic cirrhosis as well as the inability to determine underlying alcohol use, patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis (n = 10514) were analyzed as a separate cohort entity.1,3 CLD registrants with NASH were identified using only primary or secondary diagnosis codes provided by OPTN/UNOS.1 In addition, registrants listed for acute liver failure, severe alcoholic hepatitis, hepato-cellular carcinoma, retransplantation, or simultaneous organ transplantation including those listed for liver and kidney transplant were also excluded from the analysis.

Study Outcomes

Annual trends and outcomes among WL registrants and liver transplant recipients were analyzed to determine the percentage or contribution due to ALD. Annual age-specific prevalence or incidence for WL registrants due to ALD was calculated from all CLD WL registrants. We initially grouped WL registrants in 5- and 10-year age groups in the sensitivity analysis. Due to the small number of young adult WL registrants, the age-specific cohorts were categorized as young adults (18–39 years of age), middle-aged adults (40–59 years of age) and older adults (≥60 years of age). In a subanalysis, we examined age- and sex-specific trends in ALD. WL additions were defined as new or initial WL registrations. WL registrants were defined as preexisting registrants awaiting LT plus new or initial WL additions. Clinical and demographic information at the time of WL registration included: age, sex, ethnicity or race, insurance status and type, education level, UNOS region of initial listing, diabetes mellitus, body mass index (BMI), laboratory Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, dialysis or renal replacement therapy, and portal hypertension-related complications including: (1) ascites, (2) spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), (3) severe hepatic encephalopathy (HE), and (4) portal venous thrombosis (PVT). However, the data for other complications associated with portal hypertension including esophageal varices, hepatorenal syndrome, and hepatopulmonary syndrome were not available within the OPTN/UNOS registry. In addition, laboratory MELD score at transplant and WL death were also collected.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic data and clinical characteristics were compared among ALD WL additions based on age groups. Demographic data and clinical characteristics of the study cohort were presented as numbers (proportions) for categorical variables and median (interquartile ratio) for continuous variables. Continuous variables were compared using either the Student t test or Mann Whitney U test for comparisons between 2 groups and 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis test for more than 2 group comparisons as appropriate.

Similar to previous liver transplant WL time trend analyses, age-standardized incidence rates were calculated for annual ALD WL additions and WL deaths.4 The number of ALD WL additions were listed annually were tabulated into age categories using the entire annual US population estimates as the denominator (http://www.census.gov/cps) and standardized to the 2000 US population (http://seer.cancer.gov/popdata/index/htm) using the direct method. We considered the ALD WL additions as count time series with linear trend and employed the generalized linear mode (GLM) methodology to model the observations. We fit the model to this time series for each age group using the function “tsglm” from package “tscount” in R version 3.3.3 (http://www.r-project.org). We chose the log-linear model with logarithmic link to account for negative covariate effects. To adjust for the distribution of age, we divided patients into 3 age groups (18–39 years of age, 40–59 years of age, and >60 years of age) and developed a model for each of the groups. In addition, we also adjusted for overall change in annual WL additions and percentage of males.

Cox regression models were constructed to evaluate independent predictors for 1-year WL mortality among the WL registrants with ALD with LT as a competing risk.9 The risk of WL mortality was modeled from the initial date of WL registration. Forward stepwise regression was performed with entry and exit criteria set to P = 0.10. Variables with biological plausibility for association with WL mortality (sex and portal vein thrombosis)10 were included in the multivariate analysis even if P value was above the threshold. WL mortality was modeled among WL additions from 2014 to 2016 to reduce the bias of HCV-related WL mortality before and after the introduction of DAA therapy in late 2013.

We compared baseline demographics and clinical characteristics among age-specific ALD cohorts as well as ALD, NASH and HCV WL additions during the last 5-years in the study period from 2012 to 2016. In our sensitivity analysis, this 5-year time-period was chosen over the entirety of the study period to accurately reflect the rapid rise and demographic shifts associated with the current landscape of ALD-related WL additions, which was observed to occur from 2012 onward. Patients with missing data on indication for LT and WL survival follow-up and outcomes accounted for <1% and were excluded from our regression analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS statistical package (version 9.4, Cary, NC) and R statistical package (version 3.3.3, http://www.r-project.org). Statistical significance was met with a P value <0.05.

RESULTS

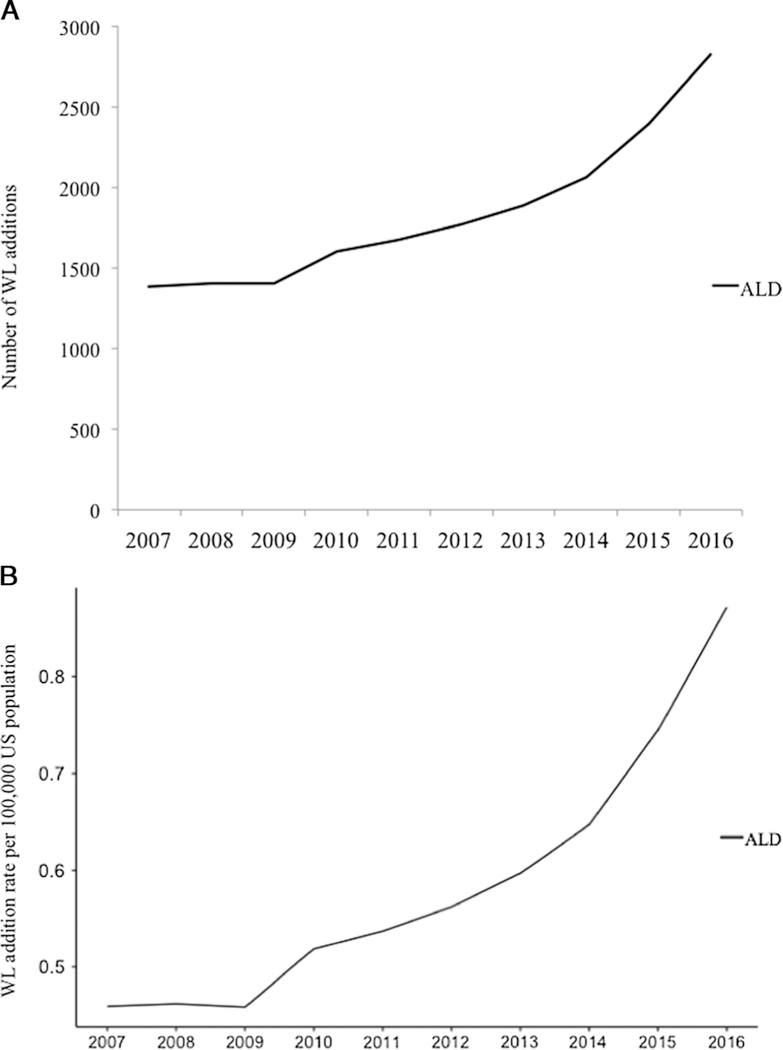

During the study period from 2007 to 2016, there were 90187 WL additions with CLD for LT, of which 18399 (20.4%) were due to ALD. The annual number of ALD WL additions doubled from 1384 in 2007 to 2819 in 2016, with a sharp rise observed from 2012 onward (Figure 1A). In 2016, ALD WL additions constituted 27.9% of all CLD WL additions (n = 10090).

FIGURE 1.

Annual trends in chronic liver disease WL registrants with alcoholic liver disease in the United States from 2007 to 2016. A, Annual number of alcoholic liver disease WL additions by listing year. B, Annual age-standardized alcoholic liver disease WL additions (initial) rate per 100000 United States population.

Baseline Demographics and Clinical Demographics

Age-specific Cohorts

Young (18–39 years), middle-aged (40–59 years) and older adults (≥60 years) constituted 6.8% (n = 1253), 61.8% (n = 11372) and 31.4% (n = 5774) of all ALD WL additions, respectively. Differences in demographics and clinical characteristics among young, middle-aged, and older adult ALD WL additions during the 5-year period from 2012 to 2016 are shown in Table 1. In our sensitivity analysis, this 5-year time-period was chosen over the entirety of the study period to reflect the rapid rise and demographic shifts associated with the current landscape of ALD-related WL additions, which was observed to occur from 2012 onward (Figure 1A). Caucasians accounted for over 70% of ALD WL additions among all 3 cohorts. Compared to middle-aged and older adults, young adults with ALD had a higher proportion of females (young adults, 34.3%; middle-aged adults, 28.5%; older adults 20.5%; P < 0.001) and those with Medicaid insurance (young adults, 39.6 %; middle-aged adults, 24.0%; older adults 8.6%; P < 0.001). Moreover, young adults presented at listing with a significantly higher severity of underlying liver disease compared to their older counterparts. Young adults with ALD presented with a higher median MELD scores (18–39 years, median MELD 25; vs. 40–59 years, median MELD 20; vs. ≥ 60 years, median MELD 19; P < 0.001) as well as a higher prevalence of patients with SBP (young adults, 12.9 %; middle-aged adults, 11.6%; older adults 8.5%; P < 0.001), severe HE (young adults, 11.4%; middle-aged adults, 8.4%; older adults 8.8%; P < 0.001) and need for renal replacement therapy (young adults, 18.4 %; middle-aged adults, 11.0%; older adults 8.2%; P < 0.001).

TABLE 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics among alcoholic liver disease WL additions by age group from 2012 to 2016

| Age groups, y | 18–39 (n = 855) | 40–59 (n = 6405) | ≥ 60 (n = 3020) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 293 (34.3) | 1823 (28.5) | 619(20.5) | <0.0001 |

| Male | 562 (65.7) | 4582 (71.5) | 2401 (79.5) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 625 (73.1) | 4859 (75.9) | 2399 (79.4) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 41 (4.8) | 230 (3.6) | 107 (3.5) | |

| Hispanic | 142 (16.6) | 1083 (16.9) | 432 (14.3) | |

| Asian | 24 (2.8) | 115(1.8) | 53 (1.8) | |

| Other | 23 (2.7) | 118(1.8) | 29 (1) | |

| Insurance type, n (%) | ||||

| Private | 413 (48.3) | 3857 (60.2) | 1430 (47.4) | <0.0001 |

| Medicaid | 339 (39.6) | 1539(24.0) | 259 (8.6) | |

| Medicare | 68 (8.0) | 784 (12.2) | 1199 (39.7) | |

| Other | ||||

| Median BMI (IQR) | 26.82 (23.30, 31.45) | 27.56(24.11,31.82) | 27.65 (24.55,31.24) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 52 (6.1) | 1153 (18.1) | 798 (26.5) | <0.0001 |

| Median initial MELD score (IQR) | 25 (18,34) | 20 (15, 29) | 18 (13, 24) | <0.0001 |

| Ascites, n (%) | 734 (85.9) | 5511 (86.1) | 2507 (83.0) | <0.0001 |

| SBP, n (%) | 109 (12.9) | 730 (11.6) | 255 (8.5) | <0.0001 |

| Severe encephalopathy, n (%) | 97 (11.4) | 539 (8.4) | 266 (8.8) | 0.0171 |

| Dialysis prior week, n (%) | 157 (18.4) | 705 (11.0) | 249 (8.2) | <0.0001 |

| Portal vein thrombosis, n (%) | 29 (3.4) | 290 (4.6) | 191 (6.4) | <0.0001 |

| Median time to transplant, in days (IQR) | 14(6, 55) | 32 (9, 127) | 47 (13, 146) | <0.0001 |

| Overall WL mortality, n (%) | 68 (8.0) | 622 (9.7) | 353 (11.7) | 0.0010 |

| Median time to WL death, in days (IQR) | 75 (12, 170) | 95 (25, 330) | 138 (40,330) | 0.0016 |

Alcoholic Liver Disease, NASH and HCV WL Registrants

Demographics and clinical characteristics were compared among ALD, HCV and NASH WL additions from 2012 to 2016. Compared to HCV and NASH WL additions, ALD WL additions were found to be significantly younger (ALD, median age 54; HCV, median age 60; NASH, median age 58; P < 0.001) with a higher prevalence of males (ALD, 73.6%; HCV, 71.8%; NASH, 51.1%; P < 0.001) seen in Table 2. In addition, patients with ALD presented with a higher severity of hepatic decompensation at listing, including median MELD score (ALD, median MELD 20; HCV, median MELD 15; NASH, median MELD 17; P < 0.001) and presence of severe HE (ALD, 8.9%; HCV, 6.0%; NASH, 7.1%; P <0.001) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of demographics and clinical characteristics in ALD, NASH, and HCV WL additions from 2012 to 2016

| ALD (n = 10384) | NASH (n = 7040) | HCV (n = 13723) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median initial age (IQR) | 54 (48–61) | 60 (54–65) | 58 (54–62) | <0.0001 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 2737 (26.4) | 3440 (48.9) | 3871 (28.2) | <0.0001 |

| Male | 7647 (73.6) | 3600 (51.1) | 9852 (71.8) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 7949 (76.6) | 5689 (80.8) | 9202 (67.1) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 382 (3.7) | 122 (1.7) | 1736 (12.7) | |

| Hispanic | 1689 (16.3) | 1007 (14.3) | 2225 (16.2) | |

| Asian | 192 (1.8) | 120 (1.7) | 371 (2.7) | |

| Other | 172 (1.7) | 102 (1.4) | 189 (1.4) | |

| Median BMI (IQR) | 27.47 (24.14–31.5) | 31.78 (27.81–36.19) | 27.85 (24.63–31.85) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 1999 (19.3) | 4129(58.9) | 3479 (25.4) | <0.0001 |

| Median initial MELD score (IQR) | 20 (14, 28) | 17(13, 23) | 15(10,21) | <0.0001 |

| SBP, n (%) | 1118(10.9) | 528 (7.6) | 1078 (7.9) | <0.0001 |

| Severe encephalopathy, n (%) | 920 (8.9) | 498 (7.1) | 826 (6.0) | <0.0001 |

| Dialysis prior week, n (%) | 1113(10.7) | 585 (8.3) | 1045 (7.6) | <0.0001 |

| Portal vein thrombosis, n (%) | 527 (5.1) | 627 (9.0) | 763 (5.6) | <0.0001 |

| Median time to transplant, in days (IQR) | 36 (10–143) | 82 (21–224) | 112 (26–288) | <0.0001 |

| Overall WL mortality, n (%) | 1043 (10.0) | 785 (11.2) | 1494 (10.9) | <0.0001 |

| Median time to WL death, in days (IQR) | 106 (27–328) | 149(53–387) | 180 (57–404) | <0.0001 |

Alcoholic Liver Disease WL Additions

The linear trend can be interpreted as a yearly increase or reduction of the number of ALD WL additions, after adjusting for age and total number of WL additions. We observed the overall age-standardized ALD WL addition rate to be 0.586 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.450 to 0.722) per 100 000 US population. The age-standardized ALD WL addition rate was 0.459 per 100000 US population in 2007; nearly doubled to 0.872 per 100000 US population in 2016 (Figure 1B) and increased annually with an average annual percent change (APC) of 47.56% (95% CI: 30.33% to 64.72%). Likewise, the overall annual age-standardized ALD WL registration (preexisting WL registrants and new WL additions) rate increased during the study (Figure S1, SDC, http://links.lww.com/TP/B640).

Age-specific Secular Trends

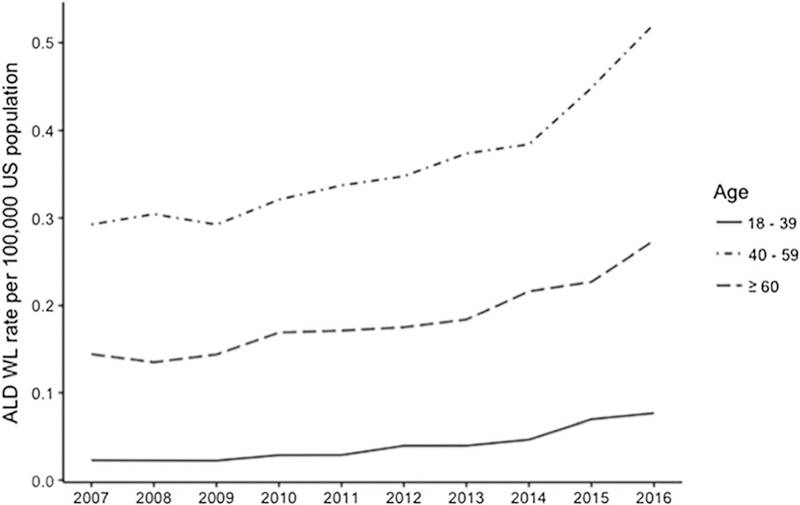

The annual number of young-adult ALD WL additions increased threefold from 2007 (n = 69) to 2016 (n = 247). Similarly, the annual number middle-aged and older adult ALD Wl additions doubled from 2007 (middle-aged adult n = 881; older adult n = 434) to 2016 (middle-aged adult n = 1686; older adult n = 886). From 2007 to 2016, ALD constituted 13.1%, 15.9% and 20.7% of young (18–39 years), middle-aged (40–59 years) and older adults with CLD added to the liver transplant WL. From 2007 to 2016, the annual percentage of CLD WL additions due to ALD increased over twofold among young and middle-aged adults.

Figure 2 demonstrates the ALD WL addition rate for young, middle-aged and older adults per 100000 US population. The ALD WL addition rate for young adults increased each year with an average APC of +10.99% (95% CI: +6.64% to +15.35%). Similarly, this rate also increased for middle-aged adults with an average APC of 9.03% (95% CI: 7.32% to 10.74%). Conversely, the ALD WL addition rate for older adults decreased by an average APC of −5.00% (95% CI: 4.87% to 15.65%) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Annual age-specific alcoholic liver disease WL addition (initial) rate per 100000 United States population from 2007 to 2016.

Gender-specific Secular Trends

Over the 10-year study period, there was a 3:1 distribution of males to females among ALD WL additions, which remained constant each year. However, the annual number of male and female ALD WL additions doubled from 2007 to 2016. In 2016, ALD accounted for over 35% of young adult and middle-aged males with CLD who were added to liver transplant WL, and 28% of young adult and middle-aged females with CLD who were added to WL. Overall, ALD accounted for 23% and 9% of older adult male and older adult female CLD WL additions, respectively.

WL Mortality in Alcoholic Liver Disease

From 2007 to 2016, there were 12481 WL registrants (preexisting and new WL additions) with CLD who died awaiting LT. ALD accounted for 20.0% (n = 2501) of these WL registrant deaths. From 2007 to 2014, the annual number of CLD-related WL registrant deaths increased 8.6% overall, followed by a sharp 21.4% decline from 2014 to 2016. However, the annual number of ALD WL registrant deaths continued to rise each year (Figure 3) and constituted 27% of CLD WL registrant deaths in 2016.

FIGURE 3.

Annual number of alcoholic liver disease WL registrant deaths from 2007 to 2016.

The overall age-standardized ALD WL registrant death rate was 0.080 (95% CI: 0.071 to 0.089) per 100000 US population. The ALD WL registrant death rate was 0.085 per 100000 US population in 2007 and increased to 0.089 per 100000 US population in 2016. After adjusting for the total number of WL registrants, the average APC was −2.62% (95% CI: −6.19% to +0.95%) with no statistical significance observed.

After adjusting for sex and the total ALD WL, we observed that the ALD WL registrant death rate for young adults had an average APC of 0.85% (95% CI: −14.78% to +16.50%). The average APC for WL death rate in middle-aged adults was −3.02% (95% CI: −6.92% to +0.89%) and +0.05% (95% CI: −0.01% to +10.82%) in older adults. The average APC for WL death rates for overall and age-specific ALD registrants did not demonstrate statistical significance as shown with the 95% CI.

In the Cox-regression multivariate analysis assessing for 1-year risk for WL mortality with LT as a competing risk, severe HE (hazard ratio [HR], 1.60, 95% CI: 1.34 to 1.91, P < 0.001), BMI <18.5 (HR 1.53, 95% CI: 1.14 to 2.05, P = 0.005), diabetes (HR 1.15, 95% CI: 1.03 to 1.25, P = 0.012), MELD score at listing (1.02, 95% CI: 1.02 to 1.03, P < 0.001), and increasing age (HR 1.02, 95% CI: 1.02 to 1.03, P < 0.001) were found to be the independent predictors for WL mortality among ALD registrants on the liver transplant WL (Table 3). Age was not a significant risk factor for WL mortality when modeled as a continuous variable (Table 3) or categorical model (young, middle-aged and older adult cohort). In a subanalysis, we analyzed 1-year WL mortality among ALD, HCV and NASH WL additions from 2014 to 2016. However, there was no statistical difference was noted in 1-year WL mortality among the 3 cohorts on univariate analysis (ALD reference, HCV, HR 0.94, [95% CI: 0.84 to 1.05], P = 0.42; NASH, HR 1.05, [95% CI: 0.93 to 1.19], P = 0.26).

TABLE 3.

Cox regression analysis assessing risk factors for 1-year WL mortality among WL registrants with alcohol liver disease in the United States from 2007 to 2016

| Univariate HR | P | Multivariate HR | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.02 (1.01–1.02) | <0.0001 | 1.02 (1.02–1.03) | <0.0001 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Male | 0.99 (0.90–1.10) | 0.8825 | 0.99 (0.89–1.10) | 0.8207 | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Black | 1.25 (1.00–1.56) | 0.0470 | 1.22 (0.97–1.54) | 0.0891 | ||

| Hispanic | 1.17 (1.04–1.31) | 0.0065 | 1.13 (1.00–1.28) | 0.0452 | ||

| Asian | 1.14 (0.82–1.57) | 0.4421 | 1.12 (0.81–1.56) | 0.4878 | ||

| Other | 1.22 (0.88–1.70) | 0.2356 | 1.34 (0.96–1.88) | 0.0859 | ||

| MELD score at listing | 1.02 (1.02–1.03) | <0.0001 | 1.02 (1.02–1.03) | <0.0001 | ||

| Diabetes | 1.18 (1.07–1.31) | 0.0015 | 1.15 (1.03–1.23) | 0.0115 | ||

| HE | ||||||

| None | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Moderate | 1.14 (1.03–1.25) | 0.0129 | 1.12 (1.01–1.26) | 0.0411 | ||

| Severe | 1.80 (1.54–2.10) | <0.0001 | 1.603 (1.34–1.91) | <0.0001 | ||

| Ascites | 1.22 (1.07–1.39) | 0.0025 | 1.11 (0.96–1.29) | 0.1457 | ||

| Portal vein thrombosis | 0.96 (0.78–1.20) | 0.7284 | 0.93 (0.75–1.16) | 0.5125 | ||

| Dialysis prior week | 1.34 (1.17–1.55) | <0.0001 | 0.90 (0.75–1.07) | 0.2124 | ||

| SBP | 1.14 (0.99–1.32) | 0.0684 | 1.00 (0.86–1.16) | 0.9968 | ||

| BMI at listing | 0.0343 | 0.0020 | ||||

| 18.5 to < 25 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| < 18.5 | 1.37 (1.03–1.82) | 0.0333 | 1.53 (1.14–2.05) | 0.0052 | ||

| 25 to < 30 | 0.93 (0.83–1.03) | 0.1599 | 0.91 (0.81–1.02) | 0.0927 | ||

| > 30 | 0.94 (0.84–1.05) | 0.2508 | 0.90 (0.80–1.01) | 0.0639 | ||

Liver Transplantation

From 2007 to 2016, there were 52574 CLD liver transplant surgeries performed, of which ALD compromised 18.0% (n = 9481) of these transplants. ALD comprised 24.7% of LT for CLD in 2016. The annual number of liver transplant surgeries performed for ALD increased from 2007 (n = 799) to 2016 (n = 1616). From 2007 to 2016, the annual number of the liver transplant surgeries performed for ALD doubled in young and middle-aged adults reaching 27% and 29% in 2016, respectively. In addition, ALD constituted over 30% of the young and middle-aged male and over 20% of the young and middle-aged female liver transplant surgeries performed for CLD.

The age-standardized ALD LT rate was 0.308 (95% CI: 0.217 to 0.387) per 100000 US population. The ALD LT rate was 0.265 per 100000 US population in 2007 and increased to 0.500 per 100000 US population in 2016 (Figure 4). After adjusting for sex and the total ALD WL, we observed that ALD LT rate for young adults had an average APC of +5.15% (95% CI: −0.38% to 10.67%). The average APC for ALD LTrate in middle-aged adults was −3.03% (95% CI: −6.44% to +0.38%) and −12.12% (95% CI: −18.18% to 6.06%) in older adults. The average APC for LT rates for age-specific ALD registrants did not demonstrate statistical significance as shown with the 95% CI.

FIGURE 4.

Annual age-standardized alcoholic liver disease LT rate per 100000 United States population.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that the annual number of ALD-related CLD WL additions have doubled during this period. Importantly, we noted disproportionate increase in young and middle-aged adults with ALD who demonstrated a two-fold increase in WL additions. Liver transplant surgeries in older adults with ALD were observed to decline during the study period, whereas LT increased in young and middle-aged adults In 2016, 1 in 3 young-adult males and 1 in 5 young-adult females underwent LT for CLD related to ALD. Interestingly, the rise in the proportion of ALD-related WL additions coincided with the introduction of DAA agents and the subsequent decline in HCV-related WL additions. Patients with ALD had a higher severity of hepatic decompensation (ascites, SBP, and severe HE) and higher median MELD scores at listing compared with WL additions with HCV and NASH. Our results showed that ALD WL registrants with severe HE and DM are more likely to die awaiting LT.

Over the past several decades, HCV has been the leading indication for LT in the developed countries including the United States. Recent breakthroughs in antiviral therapy for HCV following the introduction of DAA agents has led to dramatic improvement in pre and postliver transplant outcomes related to HCV.4,11 With the decline in HCV-related disease burden, the focus has now shifted toward developing novel screening strategies and effective therapeutic modalities for NASH.12,13 In contrast, therapeutic options for ALD remain elusive, and abstinence has remained the cornerstone of treatment for the last 5 decades.14 Due to social stigma attached to drinking and other socio-economic factors, ALD patients generally do not seek medical care until very late in the disease course, resulting in higher disease severity at presentation. Compared to those with HCV and NASH, the registrants with ALD presented with a higher disease severity. In addition, providing access to care is a major challenge and remains a serious unmet need in this subpopulation, with only 10% of patients with alcohol misuse disorder receiving appropriate care.15 From 2006 to 2010, there were 88000 alcohol-related annual deaths in the United States, accounting for 10% of all deaths in adults aged 20–64. Although the recent surge in opioid-related deaths has resulted in public outcry and gained attention of our government, ALD remains an orphan disease despite the fact that alcohol-related deaths surpassed opioid-related deaths in 2015.16 Early intervention and increased efforts on preventative measures, linkage to care and access to rehabilitation/substance abuse treatment are critical for changing the natural history of ALD in the United States.

Socio-demographic disparities associated with the treatment gap may be contributing to the rise in ALD. We observed that young and middle-aged male and female WL additions have doubled. Although predominantly associated with males, data has shown an increase in alcohol misuse among females. Compared to males, females with ALD are more susceptible to the hepatotoxic injury at lower levels of consumption. 17 In addition, females face several barriers leading to a lower likelihood of receiving access to substance abuse treatment.18 Young-adults and adults with Medicaid insurance, who are shown to have higher prevalence of ALD than other etiologies of CLD, have lower substance abuse treatment utilization rates, which may be reflected in the observed increase in the number of ALD registrants awaiting LT. Lower treatment utilization rates and acute on chronic liver disease may explain the higher severity of disease.19,20 As high as 90% individuals who consume excessive amount of alcohol have steatosis which is clinically silent and reversible with abstinence.21 However, continued drinking will result in advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis in 10–20% of patients. Therefore, a high degree of suspicion and screening are paramount in early detection of and decreasing the progression of ALD to advanced stages and subsequent need for LT.22,23

In this study, we were unable to evaluate the impact of NASH on ALD. About 1-third of US population is estimated to have nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and 2-thirds of them consume alcohol, with significant proportion consuming moderate amounts.24,25 Although available evidence is not very strong, observational studies have shown that moderate alcohol consumption may decrease fibrosis and NASH progression, but heavy episodic alcohol consumption results in accelerated progression of NASH to cirrhosis.26 Furthermore, exposure to excessive amounts of alcohol for prolonged periods promotes insulin resistance, which is an underlying mechanism in NASH.27 Our data supports higher WL mortality among those with DM. Therefore, alcohol use should be avoided in the setting of NASH until comprehensive data become available.

Our study is limited by its retrospective design, inability to evaluate recidivism, alcohol use in other etiologies of CLD and medical therapy, and variation in policies at liver transplant centers in the United States for ALD as an indication for LT. In addition, we were unable to accurately assess the prevalence of acute on chronic hepatic decompensation or underlying severe alcoholic hepatitis in patients who were listed with a diagnosis of ALD. Our analysis evaluated only CLD related to ALD and excluded patients with concomitant diagnosis of HCV, NASH or hepatocellular carcinoma, as well those listed for severe alcoholic hepatitis; therefore, the reported impact of ALD on LT in the United States based on our study is a conservative estimate.

However, if we included WL registrants listed with a primary diagnosis of severe alcoholic hepatitis, this subcohort would account for less than <1 % of all registrants listed for alcohol-related liver disease.28 Currently, there is no consensus policy within the United States for 6 months of abstinence for patients with ALD. However, there has been recent center-specific variation in policies that have allowed carefully selected patients with alcoholic liver disease whose severity of illness does not allow them to attain 6-months of abstinence listing for LT provided they have limited psychiatric or medical comorbidities and have appropriate psycho-social support.29 Early data in the United States from pilot centers transplanting patients for severe alcoholic hepatitis have shown favorable outcomes.30 The recent surge in listing may also reflect the change in WL selection criteria for ALD.31,32 These recent center-specific trends may also account for the increase in listings for ALD-related LT as well as the high severity of illness and associated high WL mortality when these patients present for LT evaluation. Despite an increase in WL in ALD for LT and higher rate of ALD-related LT, the overall ALD-related mortality continues to rise in the United States.8

In conclusion, our results highlight the changing demographic landscape of LT in the United States as it relates to ALD and other leading indications. Our results demonstrated that ALD-related WL registrations and liver transplant surgeries in the United States have risen over the past decade with a disproportionate increase noted in young adults and middle-aged adults. Despite the higher MELD score and severe hepatic decompensation at presentation compared to NASH and HCV, ALD patients had similar WL outcomes. With this alarming rise of ALD in young adults, especially young females, our study also underscores the critical need for mobilizing resources toward increased screening practices, early detection, providing linkage to care and access to substance abuse treatments to prevent advancement to end-stage liver disease. Furthermore, newer therapeutic interventions in addition to abstinence should be explored.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by Health Resources and Services Administration contract 234-2005-37011C. The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

All authors approved the final version of the article submitted and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The authors declare no funding or conflicts of interest.

G.C. was responsible for study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the article, critcal revision of the article for important intellectual content and statistical analysis. C.G., E.R.Y., B.B.D., A.A.L., K.W., M.H., and D.K. were responsible for study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the article for important intellectual content and statistical analysis, and approval of the final draft article. A.A. was responsible for study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the article for important intellectual content and supervision of research project.

Supplemental digital content (SDC) is avaiiable for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital fiies are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.transplantournal.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Cholankeril G, Ahmed A. Alcoholic liver disease replaces hepatitis C virus infection as the leading indication for liver transplantation in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:1356–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cholankeril G, Wong RJ, Hu M, et al. Liver transplantation for nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in the US: temporal trends and outcomes. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:2915–2922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong RJ, Aguilar M, Cheung R, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:547–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flemming JA, Kim WR, Brosgart CL, et al. Reduction in liver transplant wait-listing in the era of direct-acting antiviral therapy. Hepatology. 2017; 65:804–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001 −2002 to 2012–2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. JAMA Psychiat. 2017;74:911–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prevalence of alcohol consumption from the National Survey on drug use and health, 2015, for estimating indirect AAFs for liver cancer. http://nccd.cdc.gov/DPH_ARDI/Default/Default.aspx. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- 7.Yoon YH, Chen CM. Surveillance report #105: liver cirrhosis mortality in the United States: national, state, and regional trends, 2000–2013. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim D, Li AA, Gadiparthi C, et al. Changing trends in Etiology-based annual mortality from chronic liver disease, from 2007 through 2016. Gastroenterology. Published online August 31, 2018. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim WR, Therneau TM, Benson JT, et al. Deaths on the liver transplant waiting list: an analysis of competing risks. Hepatology. 2006;43: 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Englesbe MJ, Kubus J, Muhammad W, et al. Portal vein thrombosis and survival in patients with cirrhosis. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cholankeril G, Li AA, March KL, et al. Improved outcomes in HCV patients following liver transplantation during the era of direct-acting antiviral agents. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:452–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Younossi ZM, Loomba R, Anstee QM, et al. Diagnostic modalities for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) and associated fibrosis. Hepatology. 2018;68:349–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Younossi ZM, Loomba R, Rinella ME, et al. Current and future therapeutic regimens for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2018;68:361–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh S, Osna NA, Kharbanda KK. Treatment options for alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2017; 23:6549–6570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt LA, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, et al. Ethnic disparities in clinical severity and services for alcohol problems: results from the National Alcohol Survey. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CDC. Estimated liver disease deaths include deaths with the underlying cause of death coded as alcoholic liver disease (K70), liver cirrhosis, unspecified (K74.3–K74.6, K76.0, K76.9), liver cancer (C22), or other liver diseases (K71, K72, K73, K74.0–K74.2, K75, and K76.1–K76.8). Number of deaths from Multiple Cause of Death Public-Use Data File, 2015. http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd.html. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- 17.Becker U, Deis A, Sorensen TI, et al. Prediction of risk of liver disease by alcohol intake, sex, and age: a prospective population study. Hepatology. 1996;23:1025–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuchman E Women and addiction: the importance of gender issues in substance abuse research. J Addict Dis. 2010;29:127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrews C, Abraham A, Grogan CM, et al. Despite resources from the ACA, most states do little to help addiction treatment programs implement health care reform. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34:828–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.SAMHSA. Receipt of Services for Behavioral Health Problems: results from the 2014 National Survey on drug use and health. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DR-FRR3-2014/NSDUH-DR-FRR3-2014/NSDUH-DR-FRR3-2014.htm. Accessed December 23, 2017.

- 21.Lieber CS, Jones DP, Decarli LM. Effects of prolonged ethanol intake: production of fatty liver despite adequate diets. J Clin Invest. 1965;44: 1009–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sorensen TI, Orholm M, Bentsen KD, et al. Prospective evaluation of alcohol abuse and alcoholic liver injury in men as predictors of development of cirrhosis. Lancet. 1984;2:241–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teli MR, Day CP, Burt AD, et al. Determinants of progression to cirrhosis or fibrosis in pure alcoholic fatty liver. Lancet. 1995;346:987–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams CD, Stengel J, Asike MI, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among a largely middle-aged population utilizing ultrasound and liver biopsy: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, et al. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology. 2004;40:1387–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ajmera VH, Terrault NA, Harrison SA. Is moderate alcohol use in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease good or bad? A critical review. Hepatology. 2017; 65:2090–2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang L, Sebastian BM, Pritchard MT, et al. Chronic ethanol-induced insulin resistance is associated with macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue and altered expression of adipocytokines. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31 : 1581–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puri P Cholankeril G, Myint TY, et al. Early liver transplantation is a viable treatment option in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis. Alcohol Alcohol. Published online August 7, 2018. DOI: 10.1093/alcalc/agy056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bangru S, Pedersen M, Singal AG, et al. Survey of liver transplantation practices for severe acute alcoholic hepatitis. Liver Transpl. Published online August 23, 2018. DOI: 10.1002/lt.25285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee BP, Mehta N, Platt L, et al. Outcomes of early liver transplantation for patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;155: 422–430 e421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siddiqui MS, Charlton M. Liver transplantation for alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Pretransplant selection and Posttransplant management. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1849–1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinrieb RM, Van Horn DH, Lynch KG, et al. A randomized, controlled study of treatment for alcohol dependence in patients awaiting liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:539–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.