Abstract

Purpose of Review:

E-cigarettes are available in a variety of flavors not found in traditional tobacco products (i.e., “nontraditional flavors”), which is a commonly-cited reason for e-cigarette use. This review examines the prevalence of nontraditional-flavored e-cigarette use, mechanisms through which flavorings enhance product appeal, use of nontraditional-flavored e-cigarettes for smoking cessation, and differences in these findings between youth and adults.

Recent Findings:

Nontraditional-flavored e-cigarettes are used at e-cigarette initiation by the majority of youth. These flavors enhance the appeal of e-cigarettes by creating sensory perceptions of sweetness and coolness and masking the aversive taste of nicotine. Use of nontraditional-flavored e-cigarettes is higher among youth and young adults (vs. older adults) and among nonsmokers (vs. combustible cigarette smokers).

Summary:

Nontraditional-flavored e-cigarettes are popular among youth, but may be less common among older adults and combustible cigarette smokers. Further research is needed to determine whether use of e-cigarettes in nontraditional flavors affects smoking cessation.

Keywords: electronic cigarette, vaping, flavored, flavor, appeal

INTRODUCTION

Traditional tobacco products (e.g., combustible cigarettes, smokeless tobacco) were previously available in a variety of flavors that were disproportionately used in the initiation of tobacco product use among youth (1–6). To combat this threat, regulatory agencies (e.g., U.S. Food and Drug Administration, European Parliament and the Council of the European Union) banned tobacco products with any characterizing flavors other than traditional tobacco flavor or menthol (7). However, the prohibition of flavors in these products does not currently apply to new alternative tobacco products such as electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) in the United States and in other countries across the world.

The growing popularity of e-cigarettes among youth (8) has raised concern over the public health impact of flavored e-cigarettes (9, 10). E-cigarettes are available in a wide range of flavorings not found in combustible cigarettes (11). E-cigarettes are currently the most commonly used tobacco product among U.S. youth (8, 12), and the majority of youth report use of e-cigarettes in nontraditional flavors such as fruit or candy (13). Adolescent e-cigarette users (vapers) cite the availability of e-cigarettes in these nontraditional flavors as a key reason for e-cigarette use (14). Additionally, there is concern that use of nontraditional-flavored e-cigarettes could expose youth to aerosols containing compounds of known and unknown respiratory toxicity (15).

Since e-cigarettes do not involve the combustion of tobacco and are believed by experts to be less harmful than combustible cigarettes (16), they may have the potential to be a lower risk substitute and putative harm reduction measure for cigarette smokers (17–20). Evidence from a recent clinical trial indicates that e-cigarettes may be more effective than nicotine-replacement therapies at helping smokers quit smoking (21), although earlier trials and observational studies are less conclusive (21–23). Preliminary reports also indicate that the presence of flavorings could augment the effectiveness of e-cigarettes as smoking reduction or cessation aids by encouraging their use among smokers (24).

Effective tobacco control and regulatory policies require consideration of the risks and benefits to the population as a whole (i.e., users and nonusers of tobacco products) in order to protect youth nonusers from tobacco product initiation and encourage existing combustible tobacco users to quit or reduce their use (25, 26). However, it is unknown whether the risk flavored e-cigarettes pose to youth is balanced by their potential to aid in tobacco harm reduction among adult combustible cigarette smokers (27).

The current manuscript reviews and synthesizes the extant empirical literature on e-cigarettes to: (a) document the prevalence of flavored e-cigarette use among youth and adults; and (b) identify mechanisms through which flavorings enhance product appeal; (c) assess whether flavored e-cigarettes may aid adult combustible cigarette smokers in smoking reduction and cessation; and (d) examine cross-population differences (i.e., smoking status, age, gender, race) in the use and appeal of flavored e-cigarettes.

METHODS

Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

To identify studies for inclusion in the current review we searched PubMed, Medline, Google Scholar and PsycINFO beginning in September 2016 and continuing through October 2018 using combinations of the following key words: electronic cigarette, e-cigarette, vapor, vape, vaper, flavor, flavoring, flavour, sweet, fruit, candy, appeal, like, liking, attractiveness and attractive. No publication date limits were imposed for included articles. This search resulted in a total of 287 journal articles whose abstracts were evaluated for inclusion. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (a) the study was peer-reviewed and written in English; (b) the study assessed flavored e-cigarette use (i.e., flavors other than tobacco, including menthol) or appeal among human subjects; (c) the study included original data and was conducted within the United States, or if it was an online survey it contained a portion of U.S. residents; (d) the study differentiated between e-cigarettes and other flavored tobacco products (e.g., combustible cigarettes, cigars) and (e) the study provided the age of participants. Youth were defined as those under the age of 18; young adults were defined within each study using various definitions of young adults, ranging in age from 18 to 34 years of age. Because of the variability in definitions of young adults, and because some studies of adults did not distinguish between young adults and adults, results from young adults are presented with those of all adults. This review was restricted to studies based in the United States in order to define the scope of the review given the wide variation in regulatory environments in different countries. For the purposes of this review, the term ‘flavored e-cigarettes’ is used to refer to e-cigarette products that contain any non-tobacco flavoring, including menthol, with the exception of flavorless (unflavored) solutions. The term ‘sweet-flavored e-cigarettes’ refers to those labeled by the manufacturer with a confectionary characterizing flavor (e.g., candy, fruit), and excludes menthol, mint and other non-sweet flavorings (e.g., spice or alcohol) (28, 29).

Data Extraction and Synthesis

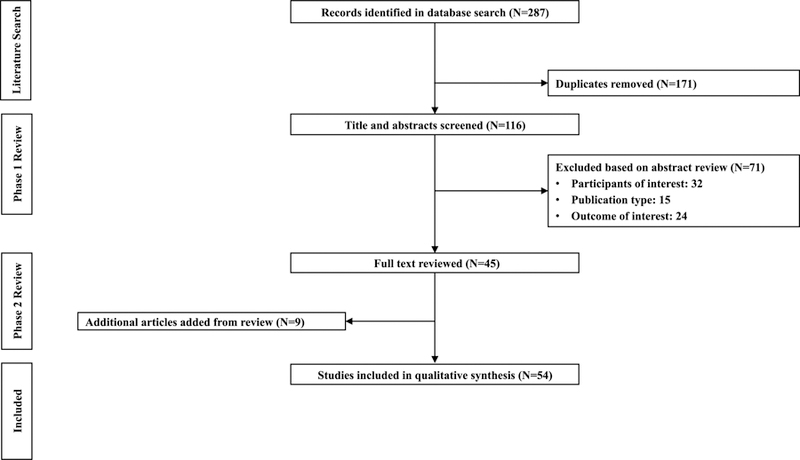

The above eligibility criteria resulted in a total of 45 eligible articles (see Figure 1). To identify additional articles for inclusion, we conducted a manual search of the references in each of the included articles. After searching the references, 9 additional articles were included in this review, resulting in a total of 54 articles. Author NG extracted data and conducted a qualitative synthesis of all included studies.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for search and inclusion of reviewed studies Note. Exclusion for participants of interest = Sample did not include US particpants. Exclusion for publication type = Not orginal data, not peer-reviewed, not english language. Exclusion for outcome of interest = Study did not assess flavored e-cigarettes.

RESULTS

Prevalence of Flavored E-Cigarette Use among Youth

Several U.S. cross-sectional surveys have documented the prevalence of flavored e-cigarette use among youth (age ≤18; Table 1). Data from wave 1 (2013–2014) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study demonstrate that flavored e-cigarettes are frequently used by youth (12–17 years old) at e-cigarette initiation, as 81.0% of e-cigarette ever-users and 85.3% of past 30-day e-cigarette users reported that the first e-cigarette they used was flavored (30), and 80% of youth who vaped before age 15 used flavored e-cigarettes (31). In the 2014 National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS), 63.3% of adolescent past 30-day vapers (aged 11–18) reported using flavored e-cigarettes (a weighted national estimate of 1.58 million flavored e-cigarette users) (32). The results of regional studies support and extend these findings; in a 2015 study of Texas youth aged 12 to 17 years old, nearly all of current vapers (97.9%) reported using flavored e-cigarettes and initiating vaping with a flavored e-cigarette (98.6%) (33).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Flavored E-Cigarette Use among Youth and Adults

| Citation | Population | Study Design | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of Flavored E-Cigarette Use among Youth | |||

| Ambrose et al. (2015) | 13,651 youth M age (SD) = 14.5 (0.02) |

Cross-Sectional Survey National Study (PATH) | 81.0% of ever-vapers reported using a flavored e-cigarette at initiation 85.3% of past 30-day vapers reported currently using flavored e-cigarettes |

| Bold et al. (2016) | 340 youth ever-vapers M age (SD) = 15.6 (1.2) |

Longitudinal Survey Connecticut | Initial use e-cigarettes due to the presence of “good” flavorings predicted continued e-cigarette use and more frequent past 30-day e-cigarette use at 6-month follow-up |

| Chen et al. (2017) | 18,392 youth Age 11–18 |

Cross-Sectional Survey National Study (NYTS) | Flavored e-cigarette use was associated with increased susceptibility to combustible cigarette smoking among non-smoking youth (aOR=3.8; p < 0.0001) |

| Corey et al. (2014) | 22,007 youth Age 11–18 |

Cross-Sectional Survey National Study (NYTS) | 63.3% of current vapers used flavored e-cigarettes An estimated 1.58 million high school and middle school students used a flavored e-cigarette in 2014 |

| Dai et al. (2016) | 2,017 adolescents Past 30-day vapers Age 11–18 |

Cross-Sectional Survey National Study (NYTS) | 60.9% of past 30-day vapers reported using flavored e-cigarettes Flavored e-cigarette use was associated with increased intentions to initiate combustible cigarette use among never-smokers (aOR = 5.7; p < 0.0001) Flavored e-cigarette use was associated with reduced intentions to quit tobacco use among smokers (aOR = 0.6; p = .006) |

| Harrell et al. (2016) | 3,907 Youth Age 12–17 |

Cross-Sectional Survey Texas | 97.9% of ever-vapers reported using flavored e-cigarettes 98.6% of vapers initiated e-cigarette use with a flavored e-cigarette |

| Morean et al. (2018) | 396 high school vapers M age (SD) = 16.18 (1.2) 42.2% smokers |

Cross-Sectional Survey Connecticut | Preferences for fruit- and dessert-flavored e-cigarettes were significantly associated with increased frequency of past 30-day e-cigarette use (ps < 0.007). |

| Schneller et al. (2018) | 415 youth vapers Age 12–17 |

Cross-Sectional Survey National Study (PATH) | 79.3% of youth reported using flavored e-cigarettes |

| Villanti et al. (2017) | 13,651 youth Age 12–17 |

Cross-Sectional Survey National Study (PATH) | 81% of youth reporting using a flavored e-cigarette at first use 80% of youth who vaped before age 15 used a flavored e-cigarette |

| Prevalence of Flavored E-Cigarette Use among Adults | |||

| Berg (2016) | Vapers and Smokers Age 18–34 59.3% smokers |

Cross-Sectional Survey Online | 67% of current vapers used sweet flavored e-cigarettes 60.2% used e-cigarettes because, “They come in appealing flavors” 59.5% used e-cigarettes because, “I like experimenting with various flavors” |

| Bonhomme et al. (2016) | 3,434 adult vapers Age 18–65+ |

Cross-Sectional Survey | 68.2% of adult vapers used flavored e-cigarettes |

| Chen et al. (2018) | 12,383 young adults Age 18–34 |

Prospective Survey National Study (PATH) | 69.9% of young adult vapers used flavored e-cigarettes |

| Dawkins et al. (2013) | 1,347 vapers Age M (SD) = 43.4 (12.0) 16% smokers |

Online Survey | Tobacco (53%) was the most commonly used flavoring, followed by fruit (33%), menthol (28%) and chocolate/sweet (18%) |

| Etter (2016) | 2,807 vapers Age Median (IQR) = 41 (31–50) 80% former smokers |

Online Survey | Tobacco was the most commonly used flavor (35%) followed by fruit (18%), menthol (14%) Tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes were used by 44% of recent vapers (vaped 0–3 months) and 25% of long-term vapers (vaped ≥ 4-months) |

| Etter et al. (2011) | 20.6% US residents 3,587 vapers 70% former smokers Age Median (IQR) = 41 (31–50) |

Online Survey | 39% used tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes 15% used menthol-flavored e-cigarettes 14% used fruit-flavored e-cigarettes |

| Farsalinos et al. (2013) | 4,618 adult vapers Age Median (IQR) = 40 (32–49) 91.2% former smokers 48.5% US residents |

Online Survey | Fruit- (69.4) and sweet-flavored (61.4%) e-cigarettes were the most commonly used by current vapers Tobacco (69.1%) was the most common flavor used at e-cigarette initiation |

| Harrell et al. (2016) | 5,482 young adults age 18–29 6,051 adults (age ≥ 30) |

Cross-Sectional Survey | 96.7% of young adults used flavored e-cigarettes 95.2% initiated e-cigarette use with a flavored e-cigarette Fruit flavors were the most popular (83%) followed by candy/dessert (52%) and tobacco (23%) 74.0% of adult vapers reported using a flavored e-cigarette |

| McQueen et al. (2011) | 210 adult vapers Age: 18+ |

Qualitative Interviews Midwest | New vapers generally initiated e-cigarette use with tobacco or menthol flavored nicotine solutions |

| Nonnemaker et al. (2016) | 365 adult vapers Age 19–65+ |

Cross-Sectional Survey Florida | 60.4% of current e-cigarette users used menthol-flavored e-cigarettes 56.6% used candy-flavored e-cigarettes 31.8% used tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes |

| Russell et al. (2018) | 20,676 adult frequent e-cigarette users Age M (SD) = 42.5 (11.6) 15.2% ≤ 25 years of age |

Online Survey USA | In 2011, 44.8% of first e-cigarette purchases were tobacco-flavored In 2011, 17.9% of first e-cigarette purchases were fruit-flavored In 2016 20.8% of first e-cigarette purchases were tobacco-flavored In 2016 36.6% of first e-cigarette purchases were fruit-flavored |

| Schneller et al. (2018) | 2,123 adult past 30-day vapers Age 18+ |

Cross-Sectional Survey National Study (PATH) | 64.6% of adults reported using a flavored e-cigarette |

| Smith et al. (2016) | 1,443 adult tobacco users Age 18+ |

Telephone Survey | 51% of participants reported current use of flavored e-cigarettes 45% initiated vaping with flavored e-cigarettes |

| Tackett et al. (2015) | 215 adult vapers M age (SD) = 36.23 (12.97) |

Cross-Sectional Survey Midwestern States | 46.7% vaped fruit-flavored e-cigarettes 23.7% vaped candy- or dessert-flavored e-cigarettes 18.6% vaped tobacco-flavored 9.0% vaped menthol-flavored e-cigarettes |

| Villanti et al. (2017) | 3,887 young adult vapers (ages 12–17) 7,635 adult vapers (ages 18+) |

Cross-Sectional Survey National Sample (PATH) | 61% of young adult vapers used flavored e-cigarettes 46% of adult vapers used flavored e-cigarettes |

| Villanti et al. (2013) | 4,196 young adults Age 18–34 |

Cross-Sectional Survey National sample | 70 participants (1.7%) used e-cigarettes during the past 30-days 17% of past 30-day vapers used flavored e-cigarettes |

| Yingst et al. (2015) | 4,421 ever-vapers M age (SD) = 40.1 (12.7) |

Online survey | 53.5% used flavored e-cigarettes |

Note. Citations are presented in alphabetical order. MTF = Monitoring the Future. NYTS = National Youth Tobacco Survey. PATH = Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. NATS = National Adult Tobacco Survey. OR = Odds ratio. aOR = Adjusted odds ratio. Vaper = E-cigarette user. Youth < 18 years of age. Adults ≥ 18 years of age.

Preliminary evidence suggests that use of flavored e-cigarettes among youth may be associated with increased frequency and persistence of vaping following initiation. In a cross-sectional study of adolescents taken from 5 different high schools in Connecticut (aged ≤18), preference for sweet-flavored e-cigarettes was cross-sectionally associated with increased frequency of past 30-day vaping (34). Additionally, longitudinal data from this sample suggest that use of e-cigarettes due to the presence of appealing flavorings may be associated with continued e-cigarette use at a 6-month follow-up assessment (35).

Prevalence of Flavored E-Cigarette Use Among Adults

Epidemiological evidence suggests that flavored e-cigarette use has increased among adults (aged ≥ 18 years old) since 2010 (36). A 2010 qualitative study found that adult vapers ranging in age from 20–69 years typically initiated e-cigarette use with tobacco- or menthol-flavored e-cigarettes (37), and in a 2012 national survey of young adult vapers (18–34 years), only 17% reported using flavored e-cigarettes during the past 30-days (38). A series of online surveys (conducted between 2010 and 2012) found that tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes were most commonly used among adults aged 18 and older (39–41), and that vapers who used tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes were more likely to be recent vapers who started vaping within the past 3-months (vs. long-term users who had vaped for 4-months or longer) (40). In a 2012 online survey of e-cigarette ever-users, 53.5% of vapers (Mean age [M] = 40.1, standard deviation [SD] = 12.7 years) currently used flavored e-cigarettes (42), and in a 2013 telephone survey, 51% of participants (aged 18+) reported current use of flavored e-cigarettes and 45% of e-cigarette ever-users reported using a flavored e-cigarette when they initiated vaping (43).

More recent data suggests that the prevalence of flavored e-cigarette is increasing among adults and may have surpassed that of tobacco- and menthol-flavored e-cigarettes. Data from the 2014–2015 PATH study demonstrate that 64.6% of adult past 30-day vapers (aged ≥ 25) and 69% of young adults (aged 18–24) used flavored e-cigarettes (31, 44), and in the 2014 National Adult Tobacco Survey (NATS) 68.2% of past 30-day vapers (aged 18+) used flavored e-cigarettes (a weighted estimate of 10.2 million adults) (45). In two online surveys conducted between 2013 and 2014, over 67% of adults (aged 18+) used sweet-flavored e-cigarettes (46, 47), and in a 2015 national study 74% of young adults (ages 18–29) and 47% of older adults (age ≥ 30) reported using flavored e-cigarettes (33). Regional studies support this trend: in two 2013 surveys 68.2% and 81.4% of Florida and Midwestern adult vapers (aged 18+), respectively, used flavored e-cigarettes (48, 49). By 2015, 96.7% of Texas young adult e-cigarette users (18–29 years old) reported currently using flavored e-cigarettes and 95.2% initiated e-cigarette use with flavored e-cigarettes (33).

Appeal of Flavored E-Cigarettes among Youth

Data from surveys and focus groups with adolescents (12–18 years old) indicate that flavored e-cigarettes are appealing due to their pleasant taste and attractive sensory characteristics (Table 2) (30, 31, 50, 51). In a national survey of adolescent e-cigarette users (12–17 years old), 81.5% stated they used e-cigarettes, “Because they come in flavors I like” (30), and among a national sample of high school students, the second most common reason for e-cigarette use (after experimentation) was because of their good taste (51). In a 2016 survey of U.S. middle and high school e-cigarette ever-users, the second most commonly selected reason for using e-cigarettes (after use by friends or family members) was, “They are available in flavors, such as mint, candy, fruit, or chocolate” (52). In a survey of Texas youth aged 12–17 years, 72.9% reported using e-cigarettes because of the availability of appealing flavorings (33), with fruit (76%) and candy (57%) being the most commonly used flavorings (33). Importantly, 78% of flavored youth e-cigarette users in this sample stated that they would no longer vape if flavored e-cigarettes were not available (53).

Table 2.

Appeal/Risk Perceptions of Flavored E-Cigarettes among Youth and Adults

| Citation | Population | Study Design | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appeal and Risk Perceptions of Flavored E-Cigarettes among Youth | |||

| Ambrose et al. (2015) | 13,651 youth M age (SD) = 14.5 (0.02) |

Cross-Sectional Survey National Study (PATH) | 81.5% of vapers cited appealing flavors as a reason for e-cigarette use |

| Cooper et al. (2016) | 3,907 Youth 5,482 young adults 32.1% 6th graders 34.5% 8th graders 33.4% 10th graders |

Cross-Sectional Survey Texas | Youth who currently used e-cigarettes had higher odds of describing flavored (vs. non-flavored) e-cigarettes as “less harmful” (aOR = 2.84, 95% CI: 1.91, 4.21) |

| Harrell et al. (2017) | 2,483 youth Age 12–17 |

Cross-Sectional Survey Texas | 78% of youth said they would no longer use e-cigarettes if flavorings were not available |

| Harrell et al. (2016) | 3,907 youth Age 12–17 |

Cross-Sectional Survey | 72.9% of vapers used e-cigarettes because they, “Come in flavors I like” Fruit flavors were the most popular (76%), followed by candy/dessert, (57%) and tobacco (13%) |

| Kong et al. (2015) | 5,405 middle, high school and college students MS M age (SD) = 12.2 (0.9) HS M age (SD) = 15.6 (1.2) College M age (SD) = 22.1 (5.5) |

Cross-Sectional Survey Focus Groups | 43.8% of ever-vapers cited the availability of appealing flavorings as a key reason for experimentation with e-cigarettes |

| Krishnan-Sarin et al | 60 adolescent and young adult vapers M age (SD) = 18.8 (.8) |

Laboratory Study | Significant main effect of menthol on appeal (p=0.006), with 3.5% menthol (M=43.4) rated higher than 0% menthol (M=34.3). Significant main effect of menthol on improved taste (p=0.006), with 3.5% menthol (M=18.52) and 0.5% menthol (M=21.40) rated higher than 0% menthol (M=5.07) Significant main effect of menthol on sensory coolness (p<0.0001), perceived coolness increased at each successive increase in menthol concentration |

| Patrick et al. (2016) | 4,066 high school students (8th, 10th, 12th grades) | Cross-Sectional Survey National Study (MTF) | Good taste was the second most common reason for e-cigarette use among ever-vapers (37.2%) Good taste was the most common reason for vaping among frequent users |

| Pepper et al. (2016) | 1,125 adolescents M age (SD) = 15.1 (1.4) 4% smokers 5% vapers |

Experimental Survey | Adolescents stated they were more likely to try menthol-flavored (OR=4.00; p <0.01) candy-flavored OR=4.53; p < 0.01) or fruit-flavored e-cigarettes (OR=6.49, p < 0.001) than tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes Adolescents perceived fruit-flavored e-cigarettes to be less harmful than tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes (p < 0.05) Harm perceptions were partially explained (mediated) the relationship between flavor type and interest in trying e-cigarettes (p < 0.01) |

| Tsai et al. (2018) | 1,061 middle school ever-vapers 2,988 high school ever-vapers |

Cross-Sectional Survey National Study (NYTS) | 31.0% of participants cited the availability of, “flavors such as mint, candy, fruit, or chocolate” as a reason for vaping 41.1% of past 30-day e-cigarette-only users and 46.0%, of dual users used e-cigarettes because, “they are available in flavors, such as mint, candy, fruit, or chocolate” |

| Villanti et al. (2017) | 13,651 youth Age 12–17 |

Cross-Sectional Survey National Study (PATH) | “Comes in flavors that I like” was the most highly ranked reason for e-cigarette use among vapers |

| Wagoner et al. (2016) | 21 adolescents Age 13–17 |

Focus Group | The wide variety of available sweet e-cigarette flavors are appealing Pleasant orosensory (gustatory) sensations are a primary reason for flavored e-cigarette use |

| Appeal of Flavored E-Cigarettes among Adults | |||

| Amato et al. (2016) | 9,301 Adults Age 18+ |

Cross-Sectional Survey Minnesota | Current vapers (vs. former vapers) cited the availability of sweet- and menthol-flavored e-cigarettes as reasons for use |

| Audrain-McGovern et al. (2016) | 32 smokers Age M (SD) = 25.0 (3.0) 56% menthol smokers |

Laboratory study | Sweet-flavored e-cigarettes were rated as more rewarding (p = 0.001) Participants were willing to work harder to earn puffs from a sweet-flavored e-cigarette than flavorless (p < 0.0001) and took more puffs from the sweet-flavored e-cigarettes during ad-lib vaping (IRR = 2.03; p = 0.01) |

| Berg et al. (2014) | 36 smokers Age M (SD) = 36.1 (15.3) |

Longitudinal study | Flavorings are an appealing element of e-cigarettes Flavors differentiate e-cigarettes from other nicotine replacement products The availability of appealing flavors was a commonly cited reason for e-cigarette use |

| Chen et al. (2018) | 12,383 young adults Age 18–34 |

Prospective Survey National Study (PATH) | Participants who perceived e-cigarettes as less harmful than cigarettes were more likely to use flavored e-cigarettes (aOR [95% CI] = 1.59 [1.15–2.19] p = 0.005) |

| Cheney et al. (2016) | 30 young adult vapers Age M (SD) = 25 (3.8) 77% current smokers |

In-Person Interviews | Vapers cite flavored e-cigarettes were a primary attraction and reason for vaping |

| Etter et al. (2011) | 3,587 vapers Age Median (IQR) = 41 (31–50) 70% former smokers |

Online Survey | Tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes were rated as less satisfying than sweet and menthol flavorings (p < 0.01) |

| Farsalinos et al. (2013) | 4,618 adult vapers Age Median (IQR) = 40 (32–49) 91.2% former smokers |

Online Survey | Fruit (69.4%) and sweet (61.4%) flavors were the most commonly used at the time of the survey Tobacco (69.1%) was the most commonly used flavor at initiation |

| Farsalinos et al. (2015) | 7,060 vapers Age Median (IQR) = 38 (30–46) |

Online Survey | 38.6% of vapers listed the variety of flavorings in e-cigarettes as a reason for initiating vaping |

| Goldenson et al. (2016) | 20 young adult vapers Age M (SD) = 26.3 (4.6) 80% smokers |

Laboratory Study | Sweet-flavored solutions produced greater subjective appeal and perceptual sweetness than non-sweet (tobacco and menthol) e-cigarettes (ps < 0.0001). Sensory sweetness was positively associated with appeal across all flavorings (ps < 0.0001) |

| Harrell et al. (2017) | 4,326 young adults Age 18–29 |

Cross-Sectional Survey Texas | 73.5% of young adults said they would no longer use e-cigarettes if flavorings were not available |

| St Helen et al. (2018) | 14 adult vapers Age M (SD) = 32.3 (13.8) |

Laboratory Study | Average puff duration was significantly longer when using a strawberry e-liquid (M [SD] = 3.2 [1.3] s) compared to the tobacco e-liquid M [SD] = (2.8 [1.1] s) |

| Kim et al. (2016) | 35 adult vapers Age 18–65 65% smokers |

Focus group | Flavor is an exciting and fun e-cigarette product feature Favorite flavors included fruits, sweet/dessert and menthol/mint E-cigarette-only Fruit and sweet/dessert flavors reduce the harshness of nicotine The enjoyment of flavored e-cigarettes was associated with use of recent-generation e-cigarette devices (e.g., advanced personal vaporizers, mods) |

| Kim et al. (2016) | 31 e-cigarette users Age M (SD) =33.6 (10.9) 61% smokers |

Laboratory Study | Sweet-flavored solutions produced greater subjective appeal (p < 0.05) Appeal was positively correlated with sensory sweetness and coolness (ps < 0.0001) Appeal was inversely correlated with bitterness (p <0.01) Menthol was significantly cooler than the sweet and tobacco flavorings (p < 0.01) |

| Litt et al. (2016) | 88 smokers Age 18–55 |

Laboratory Study Field Study (cessation trial) | Menthol (32%) was rated as the most appealing flavor followed by cherry (30%) tobacco (24%), chocolate (10%) and flavorless (4%) |

| McDonald et al. (2015) | 87 young adults Age 18–27 32% vapers 66% smokers |

Focus Groups Semi-Structured Interviews | Flavored e-cigarettes are attractive to vapers and non-vapers Flavored e-cigarettes encourage e-cigarette initiation |

| Nonnemaker et al. (2016) | 365 adult vapers Age 19+ |

Cross-Sectional Survey Florida | Among vapers and cigarette smokers, the absence of flavors significantly reduced the price participants were willing to pay for e-cigarettes |

| Pokhrel et al. (2015) | 62 young adults M age (SD) = 25.1 (5.5) |

Focus Group | Flavorings and sensory satisfaction (i.e., pleasant smell and taste) contribute to the appeal of e-cigarettes |

| Rosbrook et al. (2016) | 32 adult smokers Age 18–45 81% menthol-smokers 16%−38% vapers |

Laboratory study | Menthol increased appeal independently of nicotine (p < 0.0001) Menthol increased perceived coolness (p < 0.0001) Menthol reduced airway irritation/harshness produced by nicotine (p < 0.0001) |

| Soule et al. (2016) | 46 adult vapers Age M (SD) = 35.1 (10.6) |

Concept Mapping Mixed-Method | “Increased satisfaction and enjoyment” and “better feel and taste than [combustible] cigarettes” were the two most commonly cited reasons for flavored e-cigarette use Flavored e-cigarette solutions increase sensory satisfaction, mask the aversive taste of nicotine and increase the reward of e-cigarettes |

| Wagoner et al. (2016) | 56 young adults Age 18–25 |

Focus Group | The variety of available flavors are appealing Good smell is a reason for flavored e-cigarette use |

| Yingst et al. (2015) | 4,421 vapers M age (SD) = 40.1 (12.7) |

Online survey | 85.4% described variety of flavor choices as important |

Note. Citations are presented in alphabetical order.

MTF = Monitoring the Future. PATH = Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. NATS = National Adult Tobacco Survey. OR = Odds ratio. aOR = Adjusted odds ratio. Vaper = E-cigarette user. Youth < 18 years of age. Adults ≥ 18 years of age.

Dual user = Concurrent e-cigarette and combustible cigarette user.

A controlled laboratory study of adolescent and young adult vapers (16–20 years of age) assessed the appeal and rewarding effects of menthol and nicotine in e-cigarettes (54). Sixty current vapers (M age = 18.8; SD = 0.8) self-administered e-cigarettes at three different menthol concentrations (0%, 0.5% or 3.5% menthol) at a single randomly-assigned nicotine condition (0, 6 or 12 mg/ml) and then rated the appeal and sensory effects of each condition. There was a significant main effect of menthol, with the highest menthol concentration (3.5%) significantly increasing e-cigarette appeal, compared to 0% menthol. Both menthol concentrations (0.5% and 3.5%) significantly improved taste and enhanced perceived coolness (54).

Perceived Harm of Flavored E-Cigarettes among Youth

Research also suggests that adolescents perceive flavored e-cigarettes as less harmful than unflavored e-cigarettes (Table 2). In a school-based survey conducted among 6th, 8th, and 10th graders, current vapers were more likely to describe flavored e-cigarettes as less harmful than tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes (55). A telephone survey that randomly assigned adolescents (M age =15.1, SD = 1.4) to one of five flavor conditions (i.e., tobacco, alcohol, menthol, candy, fruit), found that participants perceived sweet- and menthol-flavored e-cigarettes as significantly less harmful than tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes, and were significantly more likely to express interest in trying candy- (OR [95% CI] = 4.53 [1.67, 12.31]), fruit- (OR [95% CI] = 6.49 [2.48, 17.01]) and menthol-flavored e-cigarettes (OR [95% CI] = 4.00, [1.46, 10.97]), compared to tobacco flavored cigarettes (56). Subsequent mediation analyses revealed that perceived harmfulness explained a significant portion of the association between flavorings and interest in trying e-cigarettes (56).

Appeal of Flavored E-Cigarettes among Adults

Qualitative evidence demonstrates that the pleasurable taste, pleasant smell and ability of flavorings to reduce the harshness of nicotine contribute to the appeal of flavored e-cigarettes among adults over the age of 18 (Table 2; 50, 58–63). In focus groups and interviews, adult and young adult vapers note that flavored e-cigarettes encourage initiation of vaping (60, 64), and a concept mapping approach (grouping answers to prompts into clusters representing common themes) identified: (a) “Increased satisfaction and enjoyment;” and (b) “Better feel and taste than [combustible] cigarettes” as the two most common reasons for flavored e-cigarette use (65). In surveys, adult vapers (Median age = 41.0, interquartile range [IQR] = 32–49 years) rated sweet- and menthol-flavored e-cigarettes as more satisfying than tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes (39), and 85.4% of vapers (M age = 40.1, SD = 12.7) described the variety of flavor choices as an important reason for vaping (42). Additionally, adult smokers aged 19 years and above stated they would pay more money for flavored (vs. unflavored) e-cigarettes (48).

Research suggests that flavored e-cigarettes may be particularly important for young adults. In a survey of young adults residing in Texas (aged 18–29), 73.5% of flavored e-cigarette users stated they would no longer use e-cigarettes if flavored products were not available (53). Additionally, in a national prospective survey of young adults (18–34 years old), perceptions of e-cigarettes as less harmful than combustible cigarettes was prospectively associated with flavored e-cigarette use, compared to tobacco- and menthol-flavored e-cigarettes (57).

Controlled laboratory evidence demonstrates that e-cigarettes are appealing and reinforcing among adults. In two e-cigarette administration experiments that utilized similar methodologies, current vapers (M age = 26.3 and 33.6 years; 61% and 80% smokers, respectively) rated the subjective appeal and sensory effects (i.e., sweetness and bitterness) of flavored and unflavored e-cigarettes (66, 67). Fruit- and candy-flavored e-cigarettes (vs. tobacco-, menthol- and flavorless e-cigarettes) were significantly more appealing, and were rated as being subjectively sweeter (66, 67). Across all flavorings, appeal was positively associated with perceived sweetness and inversely correlated with bitterness (66, 67).

In a laboratory study designed to identify flavor preferences for a subsequent smoking reduction trial, 88 non-treatment-seeking adult smokers (M age = 25.0, SD = 3.0) administered tobacco, menthol, chocolate and cherry-flavored e-cigarettes; menthol and cherry were rated as more appealing than the tobacco-flavor (69). Another laboratory study of e-cigarette-naïve smokers (aged 18–55) found that sweet-flavored e-cigarettes (i.e., fruit and chocolate) were rated as significantly more rewarding than an unflavored (i.e., flavorless) e-cigarette (68). These subjective ratings were supported by two behavioral tasks: (a) in a progressive ratio task (i.e., task designed to assess willingness to work for a reward) participants worked nearly six-times harder for the sweet-flavored (vs. flavorless) e-cigarettes; and (b) in a 90-minute ad-lib vaping period participants self-administered the sweet-flavored e-cigarette nearly twice as frequently than the flavorless control (69). An additional experimental study suggests that sweet-flavorings may affect vaping topography, as vapers (M age = 32.3, SD = 13.8) took longer puffs when using sweet-flavored (vs. tobacco-flavored) e-cigarettes (70).

Laboratory studies have also focused specifically on the sensory effects of menthol-flavored e-cigarettes. Vapers aged 18 and above (61% smokers) rated menthol as significantly “cooler” than e-cigarettes with sweet and tobacco flavorings, and coolness was positively associated with appeal (67). In a study of adult smokers (18–45 years old; 16%−38% vapers) that manipulated menthol and nicotine concentrations, e-cigarettes with higher menthol concentrations enhanced perceptions of coolness and decreased the harshness of nicotine (71), and menthol significantly enhanced the intensity of the overall sensory experience, particularly at lower nicotine concentrations (71).

Use of Flavored E-Cigarettes for Smoking Reduction and Cessation among Adult Smokers

Data from observational and qualitative studies suggest that flavored e-cigarettes may aid adult smokers in smoking reduction and cessation efforts (Table 3). Former smokers cite the wide variety of available flavorings and superior taste of e-cigarettes as factors that aid smoking cessation (40, 46, 61), and note that restricting the availability of flavorings would make the vaping less enjoyable and reduce the appeal of e-cigarettes (46, 72). In a study of adult vape store customers (M age = 36.23, SD = 12.97), flavored e-cigarette users (vs. unflavored users) were more likely to have quit smoking (49), and in an online cross-sectional survey adult e-cigarette users (M age = 42.5, SD =11.6), who had switched from smoking cigarettes to vaping were more likely to have initiated e-cigarette use with non-tobacco flavors (36). A longitudinal cohort study of adult smokers (age ≥ 18 years) found that use of flavored e-cigarettes was associated with lower self-reported daily intensity (i.e., cigarettes/day) of cigarette smoking (73), and in a national sample of 18 to 34 year-old young adult smokers, use of flavored (vs. tobacco-flavored) e-cigarettes was prospectively associated with self-reported smoking reduction or cessation (74).

Table 3.

Use of Flavored E-Cigarettes for Smoking Reduction and Cessation among Adult Smokers

| Citation | Population | Study Design | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barbeau et al. (2013) | 11 vapers Age 18–64 |

Focus group | Flavorings were related to smoking reduction and cessation |

| Buu et al. (2018) | 2,727 smokers Age 18+ |

Prospective Survey National Study (PATH) | Use of flavored e-cigarettes was associated with lower daily quantity of cigarette smoking at 1-year follow-up (B = −2.89; p < 0.05) |

| Chen et al. (2018) | 4,645 young adult smokers (age 18–34) | Prospective Survey National Study (PATH) | Use of flavored e-cigarettes (aOR [95% CI] = 2.5 [1.6, 3.8]; p < 0.001) and use of multiple flavorings (aOR [95% CI] = 3.0 [2.1, 4.3]; p < 0.001) were associated with smoking reduction or cessation, compared to no e-cigarette use. |

| Cheney et al. (2016) | 30 young adult vapers Age M (SD) = 25 (3.8) 77% current smokers |

In-Person Interviews | Former smokers cited flavorings as a primary reason for e-cigarette use |

| Etter (2016) | 2,807 vapers Age Median (IQR) = 41 (31–50) 80% former smokers |

Online Survey | 80% of participants stated that flavors helped them quit or reduce cigarette smoking Former smokers expressed a preference for fruit or menthol flavors and cited flavored e-cigarettes as helpful in reducing and quitting smoking |

| Farsalinos et al. (2013) | 4,618 adult vapers Age Median (IQR) = 40 (32–49) 91.2% former smokers 48.5% US residents |

Online Survey | 68.9% reduced availability of flavored e-cigarettes would make vaping less enjoyable Flavored e-cigarettes “very important” for reducing or quitting smoking 39.7% the reduced availability of flavored e-cigarettes would make reducing or quitting smoking less likely Former smokers noted that restricting the availability of flavorings could make smoking cessation and reduction more difficult |

| Litt et al. (2016) | 88 smokers Age 18–55 |

Laboratory Study Smoking reduction trial | Menthol-flavored e-cigarettes resulted in the greatest decrease in cigarette consumption (p < 0.05) Participants vaped tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes most frequently (p < 0.001) |

| Russell et al. (2018) | 20,676 adult frequent e-cigarette users Age M (SD) = 42.5 (11.6) 15.2% ≤ 25 years of age |

Cross-sectional online survey | Switchers, dual users, and former smoker (vs. never-smokers) were significantly less likely to initiate e-cigarette use with sweet-flavored e-cigarettes (ORs = 0.41 – 0.58; ps < 0.001) and to currently use sweet flavors (ORs = 0.64 – 0.70; ps < 0.001) |

| Tackett et al. (2015) | 215 vapers M age (SD) = 36.23 (12.97) |

Cross-Sectional Survey Midwest | Vapers who used sweet-flavored e-cigarettes were more likely to have quit smoking (OR [95% CI] = 2.4 [1.07, 5.53]; p = 0.035) |

Note. Citations are presented in alphabetical order. OR = Odds ratio. aOR = Adjusted odds ratio. Vaper = E-cigarette user. Adults ≥ 18 years of age.

In the sole smoking reduction trial that utilized flavored e-cigarettes, smokers aged 18–55 were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions for a six-week period according to a flavor (i.e., tobacco vs. menthol vs. sweet [cherry or chocolate]) × nicotine (i.e., 0 mg/ml vs. 18 mg/mL) design and smoking and vaping behavior was assessed with a timeline follow-back method, daily interactive voice response recordings and weekly breath carbon monoxide readings (68). Participants assigned to the menthol conditions experienced the greatest reduction in daily smoking, followed by cherry and tobacco, while those assigned to chocolate condition experienced the smallest reduction in smoking (68). However, participants in the tobacco-flavored e-cigarette condition vaped most frequently (12.3 vaping episodes per day), and participants assigned to the chocolate-flavored e-cigarette displayed the lowest intensity of daily vaping (8.6 episodes per day).

Factors that Moderate the Use and Appeal of Flavored E-Cigarettes

Differences in Flavored E-Cigarette Use by Combustible Cigarette Smoking Status

Evidence suggests that use of flavored e-cigarettes may be associated with combustible cigarette smoking among youth (Table 4). In a cross-sectional survey, use of flavored e-cigarettes by never-smokers was associated with increased susceptibility to combustible cigarette smoking (75, 76), and smokers who used flavored e-cigarettes were less likely to report intentions to quit smoking, compared to youth smokers who used unflavored e-cigarettes and non-users (76). Smokers may also be more likely to use e-cigarettes with traditional flavorings, as suggested in a recent study that found a greater proportion of Connecticut high school students who were current smokers reported preferring tobacco- (7.1%) and menthol-flavored (18.6%) e-cigarettes as compared to never-smokers (0.5% tobacco, and 3.5% menthol). However, a greater proportion of current smokers also preferred sweet-flavors (62.0%) vs. never-smokers (52.1%) suggesting more positive endorsement of any flavors (traditional or nontraditional) among the group of current cigarette smokers (77).

Table 4.

Factors that Moderate the Use of Flavored E-Cigarettes among Youth and Adults

| Citation | Population | Study Design | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differences in Flavored E-Cigarettes Use by Smoking Status | |||

| Berg (2016) | Vapers and Smokers Age 18–34 832 current vapers 468 former vapers 267 never-vapers |

Online survey | Current smokers used menthol-flavored e-cigarettes the most frequently (36.4%), followed by never-smokers (34.7%) and past smokers (22.8%) More current cigarette smokers (27.4%) than never-smokers (6.1%) or former smokers (15.4%) used tobacco flavors |

| Bonhomme et al. (2016) | 3,434 adult vapers Age 18+ |

Cross-sectional Survey National Adult Tobacco Survey (NATS) | Never-smokers (84.8%) had the highest proportion of flavored e-cigarette use, followed by recent former smokers (78.1%), long-term former smokers (70.4%) and current cigarette smokers (63.2%). |

| Chen et al. (2017) | 18,392 youth Age 11–18 |

Cross-Sectional Survey National Study (NYTS) | Flavored e-cigarette use was associated with increased susceptibility to combustible cigarette smoking among non-smoking youth (aOR=3.8; p < 0.0001) |

| Dai et al. (2016) | 2,017 adolescents Past 30-day vapers Age 11–18 |

Cross-Sectional Survey National Study (NYTS) | 60.9% of past 30-day vapers reported using flavored e-cigarettes Flavored e-cigarette use was associated with increased intentions to initiate combustible cigarette use among never-smokers (aOR = 5.7; p < 0.0001) Flavored e-cigarette use was associated with reduced intentions to quit tobacco use among smokers (aOR = 0.6; p = .006) |

| Dawkins et al. (2013) | 1,347 adult vapers Age M (SD) = 43.4 (12.0) |

Online Survey | More combustible cigarette smokers (61%) used tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes than former smokers (51%; p = 0.012) |

| Etter et al. (2011) | 3,587 vapers Age Median (IQR) = 41 (31–50) 70% former smokers |

Online Survey | Current smokers were more likely to use tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes (p < 0.01) |

| Farsalinos et al. (2013) | 4,618 adult vapers Age Median (IQR) = 40 (32–49) |

Online Survey | More current smokers (53.0%) than former smokers (43.1%) used tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes (p<0.001) More former smokers (30.4%) than current smokers (24.1%) initiated e-cigarette use with sweet-flavored e-cigarettes (p=0.009) |

| Harrell et al. (2016) | 5,482 young adults (age 18–29) 6,051 adults nationwide (age ≥ 30) |

Cross-Sectional Survey Texas | Use of tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes was more common among dual users than exclusive e-cigarette users (p < 0.05) |

| Kim et al. (2016) | 35 adult vapers Age 18–65 65% smokers |

Focus Group | E-cigarette-only users (vs. dual users) preferred using fruit or sweet/dessert flavors |

| Krishnan-Sarin et al. (2014) | 3,614 high school students 1,166 middle school students HS M age (SD) = 15.6 (1.2) MS M age (SD) = 12.2 (0.9) |

Cross-Sectional Survey Connecticut | A greater proportion of current smokers (12.2%) preferred tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes than never-smokers (4.7%) A greater proportion of current smokers (62.0%) preferred menthol-flavored e-cigarettes than never-smokers (52.1%) |

| Nonnemaker et al. (2016) | 379 dual users 268 smokers 13 exclusive vapers Age 19+ |

Cross-Sectional Survey Florida | The absence of flavorings reduced the price exclusive vapers (vs. smokers and dual-users) would be willing to pay for e-cigarettes |

| Patel et al. (2016) | 2,295 smokers 153 nonsmokers Age 18+ |

Cross-Sectional Survey Online | Lighter smokers (vs. heavier smokers) expressed a preference for sweet-flavored e-cigarettes |

| Schneller et al. (2018) | 2,123 adult vapers (age 35–54) 415 youth vapers (age 12–17) 80.4% youth between the ages of 15–17 years |

Cross-Sectional Survey National Study (PATH) | Youth (vs. adults) were significantly more likely use fruit-flavored e-cigarettes (OR [95% CI] = 2.11 [1.55, 2.87]) Youth (vs. adults) were significantly less likely to use menthol/mint-flavored e-cigarettes (OR [95% CI] = 0.14 [0.06, 0.32]) Youth (vs. adults) were significantly more likely to report using 1 flavoring compared to tobacco or unflavored e-cigarette (OR [95% CI] = 2.83 [1.99, 4.03]) Youth were more likely to report using 2+ flavorings (OR [95% CI] = 5.26 [3.60, 7.68]) |

| Differences in Flavored E-Cigarettes Use by Age | |||

| Bonhomme et al. (2016) | 3,434 adult vapers Age 18+ |

Cross-sectional Survey National Adult Tobacco Survey (NATS) | Younger age was associated with flavored e-cigarette use 85.2% of 18–24 year olds used flavored e-cigarettes 51.8% of 45–64 year olds used flavored e-cigarettes |

| Chen et al. (2018) | 12,383 young adults Age 18–34 |

Prospective Survey National Study (PATH) | Younger age was associated with flavored e-cigarette use (aOR [95% CI = 1.28, [1.37, 2.41]; p < 0.001) |

| Etter (2016) | 2,807 vapers Age Median (IQR) = 41 (31–50) 80% former smokers 20.6% US residents |

Online Survey | Young adults (vs. older adults) emphasized the ability to experiment with multiple flavors as key reasons for e-cigarette use |

| Harrell et al. (2016) | 3,907 youth (age 12–17) 5,482 young adults (age 18–29) 6,051 adults (age ≥ 30) |

Cross-Sectional Survey Texas | 72.9% of youth cited flavorings as a reason for e-cigarette use 57.4% of young adults cited flavorings as a reason for e-cigarette use 47.5% of older adults used tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes at initiation 21.0% of young adults used tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes at initiation |

| Kim et al. (2016) | 35 adult vapers Age 18–65 65% smokers |

Focus Group | Younger participants (aged 18–34) were more likely to prefer flavored e-cigarettes Older adults (aged 45–65) preferred tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes |

| Kong et al. (2015) | 5,405 middle, high school and college students MS M age (SD) = 12.2 (0.9) HS M age (SD) = 15.6 (1.2) College M age (SD) = 22.1 (5.5) |

Cross-Sectional Survey Focus Groups | High school students (vs. college students) were more likely to cite flavorings as a reason for experimentation with e-cigarettes (47.0% vs. 32.8%; p < 0.001) |

| Patel et al. (2016) | 2,295 smokers 153 nonsmokers Age 18+ |

Cross-Sectional Survey Online | Younger e-cigarette users were more likely to cite flavorings as a reason for use |

| Smith et al. (2016) | 1,443 adult tobacco users Age 18+ |

Telephone Survey | Younger age (i.e., being 18–24 years old) was associated with increased odds of using flavored tobacco products at initiation |

| Villanti et al. (2017) | 23,208 adults (age 25–65+) 9,112 young adults (age 18–24) 13,651 youth (age 12–17) |

Cross-sectional surveyPATH Study | Prevalence of current flavored e-cigarette use was higher among youth (31.2%) than young adults (13.6%) and adults (7.0%) |

| Gender and Race Differences in Flavored E-Cigarette Use | |||

| Baumann et al. (2015) | 944 hospitalized smokers White age: M (SD) = 44.7 (13.2) Black age: M (SD) =46.8 (12.4) 43.0% Black 55.3% male |

Cross-sectional survey | There were race differences in flavored e-cigarette use (p < 0.001) A higher proportion of Blacks (71%) used menthol-flavored e-cigarettes compared to Whites (34%) More Whites (61%) than Blacks (3%) used tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes |

| Chen et al. (2018) | 12,383 young adults (aged 18–34) 50.6% male 72.5% White |

Prospective Survey National Study (PATH) | Female gender was associated with flavored e-cigarette use (aOR [95% CI] = 1.81 [1.33, 2.46]; p < 0.001) Black participants (vs. white) were more less likely to use flavored e-cigarettes (aOR = 0.64 [0.42, 0.99]; p = 0.04) |

| Dawkins et al. (2013) | 1,347 vapers Age M (SD) = 43.4 (12.0) 30% female 96% White |

Online Survey | Males preferred tobacco flavored e-cigarettes (p < 0.001) More females used sweet-flavored e-cigarettes (p < 0.001) |

| Kistler et al. (2017) | 34 vapers Age M (SD) = 41 (18) 56% female 68% White |

Focus group | Females (vs. males) mentioned flavor more often and preferred the variety of flavors |

| Oncken et al. (2016) | 20 adult vapers Age M (SD) = 42.2 (9.7) 45% female 70% White |

Laboratory study | Significant flavor × sex interaction (p < .01) Females (vs. males) rated e-cigarettes as significantly less appealing when using their non-preferred e-cigarette flavor |

| Patrick et al. (2016) | 4,066 high school students (8th, 10th, 12th grades) | Cross-Sectional Survey National Study (MTF) | Significantly more White (38.9%) than Black (31.9%) and Hispanic (29.6%) students reported vaping, “Because it tastes good” |

| Piñeiro et al. (2016) | 1,815 e-cigarette users M age (SD) = 39.82 (13.10) 37.5% age 30–44 33.2% female 92.1% White |

Online survey | Significant sex differences in flavored e-cigarette use (p = 0.009) 81.2 of males used flavored e-cigarettes vs. 86.1% of females 18.8% of males used tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes vs. 13.9% of females |

| Rosbrook et al. (2016) | 32 adult smokers Age 18–45 50% male 81% menthol-smokers 16%−38% vapers |

Laboratory study | Females (vs. males) rated the overall sensory effects of menthol higher in the low menthol condition (0.5% menthol) without nicotine Males (vs. females) rated irritation/harshness higher in the high-menthol (3.5%) low nicotine condition Females (vs. males) rated irritation/harshness lower at the highest nicotine concentration |

Note. Citations are presented in alphabetical order. NYTS = National Youth Tobacco Survey. PATH = Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. NATS = National Adult Tobacco Survey. OR = Odds ratio. aOR = Adjusted odds ratio. Vaper = E-Cigarette user.

Data also indicate that adult smokers (aged 18+) may use tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes at higher rates than nonsmokers (Table 4) (41, 45–47, 58). In online surveys, few adult never-smokers (6.1%) used tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes, and current smokers used tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes at higher rates than former smokers (39, 46, 47). Additionally, concurrent users of e-cigarettes and combustible cigarettes (dual users) initiated vaping with tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes at higher rates than exclusive e-cigarette users (33). Smokers and dual-users (vs. nonsmokers) also report that they would pay less money for flavored e-cigarettes (48), and heavier smokers (vs. lighter smokers) expressed a preference for tobacco-flavored (vs. flavored) e-cigarettes (78).

Differences in Flavored E-Cigarette Use by Age

Studies demonstrate that younger age is associated with higher rates of flavored e-cigarette use (31, 45, 78). A larger proportion of young adults (compared to older adults) report current flavored e-cigarette use (31, 33, 45), and younger age has been shown to be associated with increased odds of using flavored e-cigarettes at vaping initiation (33, 43). In wave 1 of the PATH study (2013–2014), flavored e-cigarette use was highest among youth (85.3%), followed by young adults (83.4%) and was lowest in adults over 25 years of age (63.2%) (31). Furthermore, among young adults (aged 18–34) younger age was associated with flavored e-cigarette use (56), and youth (12–17 years old) were significantly more likely than adults to report using fruit-flavored e-cigarettes and less likely to report using menthol- or mint-flavored e-cigarettes (44). Similarly, more Texas youth (72.9%) than young adults (57.4%) cited flavorings as a reason for e-cigarette use (33), and in a sample of Connecticut youth, 47.0% of high school students, compared to 32.8% of college students, cited flavorings as a reason for experimentation with e-cigarettes (13). In qualitative studies, young adult vapers (aged 18–45) emphasize the importance of sweet flavorings and their ability to reduce the harshness of nicotine (45, 58, 65), while older adult vapers (aged 45–65) express a preference for the taste of tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes (58).

Gender and Race Differences in Flavored E-Cigarette Use

Data suggest that the use, appeal and sensory effects of flavored e-cigarettes, particularly menthol, may also vary by gender. Qualitative interviews and observational surveys of adults (18+) suggest that more females (vs. male) vapers use flavored e-cigarettes (41, 57, 80, 81). An experiment with menthol-flavored e-cigarettes found a three-way interaction between menthol, nicotine content and female gender, with females (18–45 years of age) preferring menthol-flavored e-cigarettes, particularly in the absence of nicotine (71). In a separate study of non-treatment seeking smokers (M age = 42.2, SD = 9.7) female menthol smokers (vs. males) vaped less and rated e-cigarettes as less rewarding when presented with a tobacco-flavored e-cigarette (79).

Several studies have examined race differences in flavored e-cigarette use. In a cross-sectional survey of students in 8th, 10th, and 12th grade, significantly more White (38.9%) than Black (31.9%) and Hispanic (29.6%) students reported vaping, “Because it tastes good” (51). A prospective study of young adults aged 18–34 found that Black participants were less likely (adjusted OR [95% CI] = 0.64 [0.42, 0.99]) than White participants to use flavored e-cigarettes (57). A cross-sectional study of 944 hospitalized smokers aged 19–80 years old (55.3% male, 43.0% Black) found that Black participants (71%) used menthol-flavored e-cigarettes at higher rates than White participants (34%), whereas more White (61%) than Black participants (3%) used tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes (82).

DISCUSSION

This review demonstrates that flavored e-cigarettes are commonly used by adolescent and young adult vapers at e-cigarette initiation and during regular use following initiation. Qualitative and experimental evidence indicate that flavored e-cigarettes are appealing due to their pleasurable sensory qualities, which may suppress the aversive sensory effects of nicotine. Epidemiological evidence suggests that the prevalence of flavored e-cigarette use may differ by age and smoking status, with older adults and smokers using flavored e-cigarettes at lower rates than youth and nonsmokers.

The chemosensory science literature demonstrates that children and adolescents (vs. adults) have a strong preference for sweet flavorings in general (6), and tobacco industry documents have found that adolescents and young adults are particularly susceptible to flavored tobacco products (3, 4). Observational evidence suggests that restricting the availability of flavored combustible cigarettes in the U.S. may have reduced youth tobacco use, of both flavored and unflavored products (83). Given evidence that: (a) youth perceive flavored e-cigarettes to be less harmful than tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes; (b) flavored e-cigarettes encourage experimentation with e-cigarettes and may maintain use following initiation; and (c) flavored e-cigarette use may increase risk of combustible tobacco product use, flavored e-cigarettes may pose risks to the public health of youth.

Qualitative reports and observational evidence suggest that flavored e-cigarettes (vs. tobacco flavors) may aid adult smokers in smoking reduction and cessation efforts (73, 74). However, there is only one extant smoking reduction trial that assessed the efficacy of flavored e-cigarettes to date (68). More clinical, laboratory and epidemiological research is needed to determine whether flavored e-cigarettes, compared to tobacco flavors, can help adult smokers quit or reduce smoking.

This review extends previous research on flavored tobacco products by focusing specifically on flavored e-cigarettes. By synthesizing the extant observational and experimental data on flavored e-cigarettes, this review highlights the growing prevalence of flavored e-cigarette use among youth and adults and identifies mechanisms through which flavorings enhance the appeal of e-cigarettes. Additionally, the examination of interindividual differences (e.g., age, smoking status, gender, race) suggest that the appeal of flavored e-cigarettes may vary in different segments of the population.

In several places throughout this review we have identified gaps in the literature. A number of the studies did not distinguish between sweet, menthol and other flavorings, thus it was not possible to assess the ways in which specific flavorings differ from one another and may affect e-cigarette use. While experimental studies have examined the appeal of sweet-flavored e-cigarettes in adult and young adult populations, it is unknown if flavorings have the same effects among e-cigarette-naïve adolescents. Few prospective studies have examined trajectories of flavored e-cigarette use over time, and longitudinal data is needed to understand the impact of flavorings on developmental patterns of e-cigarette use as well as progression to or reduction of combustible tobacco product use.

Strengths of the review include the integration of epidemiological and experimental evidence and focus on specific mechanisms through which flavorings enhance e-cigarette product appeal. This review did not include studies conducted solely outside the U.S., non-English language articles or studies that did not involve human subjects (e.g., e-liquid toxicology assays, analyses of social media posts, studies focused on marketing and advertising). Additionally, while we included only articles from peer-reviewed journals, we did not assess individual study quality.

Conclusions

The majority of adolescent and young adult vapers use flavored e-cigarettes, while older adults and combustible cigarette smokers may use flavored e-cigarettes at lower rates than youth and nonsmokers. Additional data is needed to determine whether use of flavored (vs. unflavored) e-cigarettes may improve cessation outcomes among adult smokers. Systematic approaches are necessary to fully characterize the public health impact of flavored e-cigarettes and to inform evidence-based regulatory policies.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

AL, KS, JBT declare no conflicts of interest. NG accepted a job with JUUL Labs on February 10, 2019 and did not contribute to the paper after that date.

Human and Animal rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lewis MJ, Wackowski O. Dealing with an innovative industry: a look at flavored cigarettes promoted by mainstream brands. Am J Public Health 2006;96(2):244–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feirman SP, Lock D, Cohen JE, Holtgrave DR, Li T. Flavored Tobacco Products in the United States: A Systematic Review Assessing Use and Attitudes. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18(5):739–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Connolly GN. The role of sensory perception in the development and targeting of tobacco products. Addiction 2007;102(1):136–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Pauly JL, Koh HK, Connolly GN. New cigarette brands with flavors that appeal to youth: tobacco marketing strategies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(6):1601–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang L-L, Baker HM, Meernik C, Ranney LM, Richardson A, Goldstein AO. Impact of non-menthol flavours in tobacco products on perceptions and use among youth, young adults and adults: a systematic review. Tob Control 2017;26(6):709–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.*Hoffman AC, Salgado RV, Dresler C, Faller RW, Bartlett C. Flavour preferences in youth versus adults: a review. Tob Control 2016;25(S2):ii32–ii39.This systematic review details the extant chemosensory science literature regarding flavorings used in tobacco products, finding that children and adolescents (vs. adults) prefer sweet flavorings (e.g., cherry, candy, strawberry).

- 7.Carvajal R, Clissold D, Shapiro J. Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act: An Overview. The. Food & Drug LJ 2009;64:717. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang TW, Gentzke A, Sharapova S, Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Jamal A. Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2011–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67(22):629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murthy VH. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Major Public Health Concern. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171(3):209–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drazen JM, Morrissey S, Campion EW. The Dangerous Flavors of E-Cigarettes. N Engl J Med 2019; 10.1056/NEJMe1900484. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Zhu S-H, Sun JY, Bonnevie E, Cummins SE, Gamst A, Yin L, et al. Four hundred and sixty brands of e-cigarettes and counting: implications for product regulation. Tob Control 2014;23(S3):iii3–iii9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE & Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use: 1975–2017: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan, 2018.

- 13.Hong H, McConnell R, Liu F, Urman R, Barrington-Trimis JL. The impact of local regulation on reasons for electronic cigarette use among Southern California young adults. Addict Behav 2019. April;91:253–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong G, Morean ME, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S. Reasons for electronic cigarette experimentation and discontinuation among adolescents and young adults. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;17(7):847–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barrington-Trimis JL, Samet JM, McConnell R. Flavorings in electronic cigarettes: an unrecognized respiratory health hazard? JAMA 2014;312(23):2493–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Academies of Sciences E, and Medicine. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes Washington, DC: 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goniewicz ML, Knysak J, Gawron M, Kosmider L, Sobczak A, Kurek J, et al. Levels of selected carcinogens and toxicants in vapour from electronic cigarettes. Tob Control 2014;23(2):133–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goniewicz ML, Gawron M, Smith DM, Peng M, Jacob P 3rd, Benowitz NL. Exposure to Nicotine and Selected Toxicants in Cigarette Smokers Who Switched to Electronic Cigarettes: A Longitudinal Within-Subjects Observational Study. Nicotine Tob Res 2017;19(2):160–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abrams DB, Glasser AM, Pearson JL, Villanti AC, Collins LK, Niaura RS. Harm Minimization and Tobacco Control: Reframing Societal Views of Nicotine Use to Rapidly Save Lives. Annu Rev Public Health 2018;39:193–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nutt DJ, Phillips LD, Balfour D, Curran HV, Dockrell M, Foulds J, et al. Estimating the harms of nicotine-containing products using the MCDA approach. Eur Addict Res 2014;20(5):218–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hajek P, Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, Pesola F, Myers Smith K, Bisal N, et al. A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy. N Engl J Med 2019; 10.1056/NEJMoa1808779. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Hartmann-Boyce J, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Begh R, Stead LF, Hajek P. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. The Cochrane Library 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Kalkhoran S, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2016;4(2):116–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russell C, Dickson T, McKeganey N. Advice from former-smoking e-cigarette users to current smokers on how to use e-cigarettes as part of an attempt to quit smoking. Nicotine Tob Res 2018; 20(8):977–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gottlieb S, Zeller M. A nicotine-focused framework for public health. N Engl J Med 2017;377(12):1111–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Food, Drug Administration H. Deeming Tobacco Products To Be Subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as Amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; Restrictions on the Sale and Distribution of Tobacco Products and Required Warning Statements for Tobacco Products. Final rule. Federal register 2016;81(90):28973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polosa R, Rodu B, Caponnetto P, Maglia M, Raciti C. A fresh look at tobacco harm reduction: the case for the electronic cigarette. Harm reduction journal 2013;10(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yingst JM, Veldheer S, Hammett E, Hrabovsky S, Foulds J. A method for classifying user-reported electronic cigarette liquid flavors. Nicotine Tob Res 2017;19(11):1381–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krüsemann EJZ, Boesveldt S, de Graaf K, Talhout R. An E-liquid Flavor Wheel: A Shared Vocabulary based on Systematically Reviewing E-liquid Flavor Classifications in Literature. Nicotine Tob Res 2018. 10.1093/ntr/nty101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Ambrose BK, Day HR, Rostron B, Conway KP, Borek N, Hyland A, et al. Flavored tobacco product use among us youth aged 12–17 years, 2013–2014. JAMA 2015;314(17):1871–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.**Villanti AC, Johnson AL, Ambrose BK, Cummings KM, Stanton CA, Rose SW, et al. Flavored Tobacco Product Use in Youth and Adults: Findings From the First Wave of the PATH Study (2013–2014). Am J Prev Med 2017;53(2):139–151.This is an important epidemiological study that suggests that there is an inverse relation between sweet-flavored e-cigarette use (vs. tobacco and menthol flavors) and age, with younger age associated with greater rates of sweet-flavored e-cigarette use.

- 32.Corey CG, Ambrose BK, Apelberg BJ, King BA. Flavored Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;64(38):1066–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.**Harrell M, Weaver S, Loukas A, Creamer M, Marti C, Jackson C, et al. Flavored e-cigarette use: Characterizing youth, young adult, and adult users. Prev Med Rep 2016;5:33–40.This important cross-sectional survey demonstrates that flavored e-cigarettes are widely used by youth at e-cigarette initiation and during regular use. The prevalence of flavored e-cigarette use is markedly lower among adult vapers.

- 34.**Morean M, Butler E, Bold K, Kong G, Camenga D, Cavallo D, et al. Preferring more e-cigarette flavors is associated with e-cigarette use frequency among adolescents but not adults. PloS one 2018;13(1):e0189015-e.This cross-sectional study presents some of the first data that suggests that use of flavored e-cigarettes and a greater total number of e-cigarette flavorings is associated with increased frequency of past 30-day vaping among youth.

- 35.**Bold KW, Kong G, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S. Reasons for trying e-cigarettes and risk of continued use. Pediatrics 2016;138(3):e20160895.This prospective study presents novel longitudinal evidence that preference for flavored e-cigarettes may be associated with persistent e-cigarette use following initiation among youth.

- 36.Russell C, McKeganey N, Dickson T, Nides M. Changing patterns of first e-cigarette flavor used and current flavors used by 20,836 adult frequent e-cigarette users in the USA. Harm Reduct J 2018;15(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McQueen A, Tower S, Sumner W. Interviews with “vapers”: implications for future research with electronic cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res 2011;13(9):860–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Villanti AC, Richardson A, Vallone DM, Rath JM. Flavored tobacco product use among US young adults. Am J Prev Med 2013;44(4):388–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Etter JF, Bullen C. Electronic cigarette: users profile, utilization, satisfaction and perceived efficacy. Addiction 2011;106(11):2017–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Etter JF. Characteristics of users and usage of different types of electronic cigarettes: findings from an online survey. Addiction 2016;111(4):724–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dawkins L, Turner J, Roberts A, Soar K. ‘Vaping’ profiles and preferences: an online survey of electronic cigarette users. Addiction 2013;108(6):1115–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yingst JM, Veldheer S, Hrabovsky S, Nichols TT, Wilson SJ, Foulds J. Factors associated with electronic cigarette users’ device preferences and transition from first generation to advanced generation devices. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17(10):1242–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith DM, Bansal-Travers M, Huang J, Barker D, Hyland AJ, Chaloupka F. Association between use of flavoured tobacco products and quit behaviours: findings from a cross-sectional survey of US adult tobacco users. Tob Control 2016;25(S2):ii73–ii80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schneller LM, Bansal-Travers M, Goniewicz ML, McIntosh S, Ossip D, O’Connor RJ. Use of flavored electronic cigarette refill liquids among adults and youth in the US—Results from Wave 2 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study (2014–2015). PloS one 2018;13(8):e0202744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bonhomme MG, Holder-Hayes E, Ambrose BK, Tworek C, Feirman SP, King BA, et al. Flavoured non-cigarette tobacco product use among US adults: 2013–2014. Tob Control 2016;25(S2):ii4–ii13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farsalinos KE, Romagna G, Tsiapras D, Kyrzopoulos S, Spyrou A, Voudris V. Impact of flavour variability on electronic cigarette use experience: an internet survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013;10(12):7272–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berg CJ. Preferred flavors and reasons for e-cigarette use and discontinued use among never, current, and former smokers. Int J Public Health 2016;61(2):225–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nonnemaker J, Kim AE, Lee YO, MacMonegle A. Quantifying how smokers value attributes of electronic cigarettes. Tob Control 2016;25(e1):e37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tackett AP, Lechner WV, Meier E, Grant DM, Driskill LM, Tahirkheli NN, et al. Biochemically verified smoking cessation and vaping beliefs among vape store customers. Addiction 2015;110(5):868–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wagoner KG, Cornacchione J, Wiseman KD, Teal R, Moracco KE, Sutfin E. E-cigarettes, hookah pens and vapes: Adolescent and young adult perceptions of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18(10):2006–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patrick ME, Miech RA, Carlier C, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE. Self-reported reasons for vaping among 8th, 10th, and 12th graders in the US: Nationally-representative results. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;165:275–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsai J, Walton K, Coleman BN, Sharapova SR, Johnson SE, Kennedy SM, et al. Reasons for Electronic Cigarette Use Among Middle and High School Students — National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2016. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2018;67(6):196–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.**Harrell MB, Loukas A, Jackson CD, Marti CN, Perry CL. Flavored tobacco product use among youth and young adults: what if flavors didn’t exist? Tob Regul Sci 2017;3(2):168–73.In this survey 78% of adolescent vapers reported that they would no longer use e-cigarettes if they were not available in flavored varieties; this data suggests that the availability of flavored e-cigarettes may be an important factor that contributes to youth vaping.

- 54.*Krishnan-Sarin S, Green BG, Kong G, Cavallo DA, Jatlow P, Gueorguieva R, et al. Studying the interactive effects of menthol and nicotine among youth: An examination using e-cigarettes. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;180:193–199.This is one of the few laboratory experiments to assess the effects of flavored e-cigarettes among youth. E-cigarettes with high concentrations of menthol (3.5%) were found to increase product appeal and enhance taste and sensory coolness.

- 55.Cooper M, Harrell MB, Pérez A, Delk J, Perry CL. Flavorings and Perceived Harm and Addictiveness of E-cigarettes among Youth. Tob Regul Sci 2016;2(3):278–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pepper J, Ribisl K, Brewer N. Adolescents’ interest in trying flavoured e-cigarettes. Tob Control 2016;25(S2):ii62–ii66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen JC, Green KM, Arria AM, Borzekowski DLG. Prospective predictors of flavored e-cigarette use: A one-year longitudinal study of young adults in the U.S. Drug alcohol depend 2018;191:279–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim H, Davis AH, Dohack JL, Clark PI. E-Ciga Use Behavior and Experience of Adults: Qualitative Research Findings to Inform E-Cigarette Use Measure Development. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;19(2):190–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pokhrel P, Herzog TA, Muranaka N, Fagan P. Young adult e-cigarette users’ reasons for liking and not liking e-cigarettes: A qualitative study. Psychol Health 2015;30(12):1450–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McDonald EA, Ling PM. One of several ‘toys’ for smoking: young adult experiences with electronic cigarettes in New York City. Tob Control 2015;24(6):588–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cheney MK, Gowin M, Wann TF. Electronic Cigarette Use in Straight-to-Work Young Adults. Am J Health Behav 2016;40(2):268–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Amato MS, Boyle RG, Levy D. How to define e-cigarette prevalence? Finding clues in the use frequency distribution. Tob Control 2016;25(e1):e24–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berg CJ, Barr DB, Stratton E, Escoffery C, Kegler M. Attitudes toward e-cigarettes, reasons for initiating e-cigarette use, and changes in smoking behavior after initiation: a pilot longitudinal study of regular cigarette smokers. Open J Prev Med 2014;4(10):789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Farsalinos KE, Romagna G, Voudris V. Factors associated with dual use of tobacco and electronic cigarettes: A case control study. Int J Drug Policy 2015;26(6):595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Soule EK, Rosas SR, Nasim A. Reasons for electronic cigarette use beyond cigarette smoking cessation: A concept mapping approach. Addict Behav 2016;56:41–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goldenson NI, Kirkpatrick MG, Barrington-Trimis JL, Pang RD, McBeth JF, Pentz MA, et al. Effects of Sweet Flavorings and Nicotine on the Appeal and Sensory Properties of e-Cigarettes Among Young Adult Vapers: Application of a Novel Methodology. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;168:176–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim H, Lim J, Buehler SS, Brinkman MC, Johnson NM, Wilson L, et al. Role of sweet and other flavours in liking and disliking of electronic cigarettes. Tob Control 2016;25(Suppl 2):ii55–ii61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]