Abstract

The purpose of this work was to synchronously acquire proton (1H) and sodium (23Na) image data on a 3T clinical MRI system within the same sequence, without internal modification of the clinical hardware, and to demonstrate synchronous acquisition with 1H/23Na-GRE imaging with Cartesian and radial k-space sampling. Synchronous dual-nuclear imaging was implemented by: mixing down the 1H signal so that both the 23Na and 1H signal were acquired at 23Na frequency by the conventional MRI system; interleaving 1H/23Na transmit pulses in both Cartesian and radial sequences; and using phase stabilization on the 1H signal to remove mixing effects. The synchronous 1H/23Na setup obtained images in half the time necessary to sequentially acquire the same 1H and 23Na images with the given setup and parameters. Dual-nuclear hardware and sequence modifications were used to acquire 23Na images within the same sequence as 1H images, without increases to the 1H acquisition time. This work demonstrates a viable technique to acquire 23Na image data without increasing 1H acquisition time using minor additional custom hardware, without requiring modification of a commercial scanner with multinuclear capability.

Keywords: sodium, multinuclear imaging, metabolic imaging, radiofrequency coils, dual-nuclear mri

INTRODUCTION

Sodium (23Na) is the second most abundant NMR nucleus in human body after 1H. Sodium MRI is less sensitive than 1H-MRI, due to the relatively low in vivo 23Na concentrations, rapid bi-exponential signal decay1, and a low gyromagnetic ratio2. Despite these challenges, 23Na-MRI is currently being pursued as a complement to clinical 1H-MRI to enable better characterization and assessment of tumor viability3,4, cartilage health5–8, renal failure9,10, tissue damage following stroke11,12, and multiple sclerosis13.

A significant barrier to 23Na-MRI in clinical settings is the need for expensive and specialized hardware to enable non-proton imaging, in addition to the increased time requirements for obtaining both 23Na and 1H data that are typically acquired sequentially in separate MRI sequences3–13. By acquiring both datasets within a single pulse sequence, synchronous 1H/23Na imaging has the potential to obtain both 1H-MRI and 23Na information without increasing acquisition time, thereby improving the practicality of 23Na-MRI.

Synchronous multinuclear imaging (SMI), where images from more than one nuclei are acquired in a single pulse sequence, has been investigated on clinical 1.5T14, 3T15–21, and 7T17,22 MRI systems, imaging 1H synchronously with 23Na14–17, 19F18, 3He19, and 31P20,22 and obtaining synchronous triple-nuclei 1H/3He/129Xe images21. Although SMI was demonstrated initially in 198614,23, only recently has there been renewed interest in SMI on human research systems, with the majority of publications using a software-only method on Philips systems15,17–19,21, and additional hardware added to enable SMI on a Siemens system22.

The increased complexities in both hardware and pulse sequence have limited the application of SMI on clinical MRI systems, as typical clinical systems are capable of irradiating or receiving only at 1H frequency. Any system that is equipped with a broadband amplifier and that can demodulate both sodium and proton frequencies has the basic hardware capability to do SMI through interleaving proton and non-proton pulses and acquisition24. Even when a system has dual resonant 1H/23Na coils and multi-nuclear MR capability, SMI is still uncommon because: 1) non-proton imaging or spectroscopy on most human research systems is enabled by a switch that limits transmission to a single RF amplifier at any given time; and, 2) human research systems lack appropriate software and/or demodulation hardware that enables reception of two frequencies in a sequence. Our scanner is hard-coded such that it will not allow reception of two frequencies within the same sequence. However, the ability to transmit at two frequencies within a sequence by sequentially switching between RF transmission with the 1H RF amplifier and broadband RF amplifier, which is commonly done during non-proton spectroscopy, allows us to add additional receive hardware to acquire synchronous data by manipulating both 23Na and 1H spin systems within the same pulse sequence.

Previous implementations of SMI have demonstrated excitation, readout, and encoding occurring for two nuclei at exactly the same time (“simultaneous”)15,18 or interleaved with rapid succession of 1H and the non-proton steps (“interleaved”)14,19,21,23,24. One implementation demonstrated both interleaved and simultaneous imaging with the use of additional hardware22. Many of the SMI techniques used separate 1H and 23Na demodulation hardware channels to acquire the 1H/23Na signals at each respective frequency either internal to the scanner or through additional custom transmit/receive hardware. In order to avoid the need for two frequency demodulation channels, which require either completely custom acquisition software/hardware or internal modification of the MRI machine, our method down-converts the 1H signal to the 23Na frequency to acquire both nuclei on the system’s unmodified hardware. Our novel SMI technique uses our MRI system’s ability to do sequential 1H/23Na excitation, and enables dual-nuclear simultaneous receive by down-converting the proton signal to 23Na frequency during 1H/23Na readout.

In vivo 1H/23Na-SMI has been reported in the brain14, breast16, and knee15,17, with Cartesian gradient echo (GRE) imaging for both nuclei, which is inefficient for obtaining 23Na images that have a short T2* (~15 ms). de Bruin has also shown SMI with radial sampling using a software-based interleaved imaging approach17. In this manuscript, we present a novel technique for SMI to obtain synchronous 1H/23Na-GRE images with Cartesian sampling. We have also performed in vivo 23Na/1H-SMI with a 3D GRE sequence and simultaneous radial sampling, which greatly improves 23Na image quality by allowing for short TRs and sampling 23Na before significant T2* signal loss25.

METHODS

Hardware

Custom add-on hardware shown in Figs. 1&2 was developed and used with a 3T clinical MRI system (Tim-Trio, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany), equipped with multinuclear capability, to sample both 23Na and 1H MR signals within the same acquisition at the same carrier frequency. The stock multinuclear option equips the MRI system with an additional broadband RF amplifier, and a switch box that can switch between the 1H and broadband RF amplifiers. The broadband RF amplifier is used for non-proton RF transmission and the main baseband 1H RF amplifier is used for proton RF transmission. The baseband and broadband signals are combined into a single transmit channel that is supplied to the RF coil.

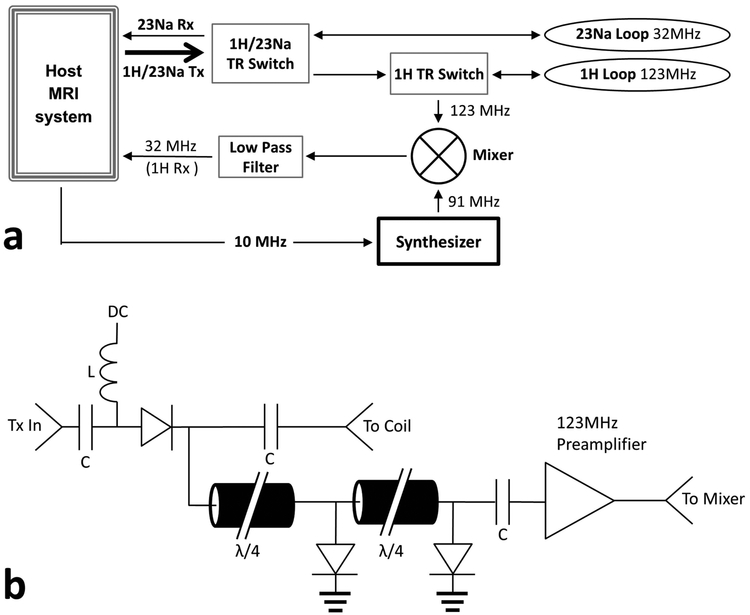

Fig. 1.

(a) Transmit/receive hardware for both 1H and 23Na. Arrows indicate transmit / receive pathways. The host system provided both 1H and 23Na transmit pulses through a single channel, which passed through a commercial 1H/23Na TR switch. The 23Na coil connected directly to the 1H/23Na TR switch; the 1H channel runs through a second 1H TR switch before connecting to the coil. The second 1H TR switch was necessary to redirect the 1H RF for mixing and down-conversion to 32MHz for simultaneous 1H/23Na reception. An attenuator is necessary due to the significant signal difference between 23Na and 1H. (b) TR switch schematic for 1H. The 1H signal is amplified at 123MHz before down-conversion to 32MHz.

Fig. 2.

(a) Linear sodium coil and linear proton coil concentric with each other and decoupled using traps. (b) Quadrature sodium coil (central circular loop and butterfly loop) and linear proton coil, each overlapped to minimize mutual inductive coupling.

Transmit switching for both 1H and 23Na channels uses a custom dual-resonant TR switch with passive traps to separate the 1H and 23Na transmit frequencies26. The TR switch contains two connectors for transmit/receive on both 1H and 23Na channels for standard non-synchronous single-frequency operation.

Because the dual-resonant TR switch is also intended for single-nuclear imaging of either nuclei, an additional 1H TR switch is placed between the 1H output of the dual-resonant TR switch (Fig. 1a) and coil. The 1H TR switch is to direct the 1H NMR signal toward a second 23Na receive channel, down-convert and receive the 1H signal at the carrier frequency of 32.6 MHz (the same frequency as 23Na) through the scanner, without modifying the current system hardware. The 1H TR switch incorporates standard TR switch circuitry, such as a serial PIN diode, quarter-wave cables that are connected by PIN diodes to ground for preamplifier protection, and an RF preamplifier (Fig. 1b). The host MRI system provides DC biasing that is software controlled to switch the 1H PIN diodes. During 1H transmission, a forward-bias current (+ 100mA) shorts the PIN diodes in the 1H TR switch (Fig. 1b) so that the 1H RF transmit can easily pass through, but is negatively biased (− 30V) during RF reception to ensure that the receive signal is directed to the 1H preamplifier (Fig. 1b). The inductance of the RF chokes (L in Fig. 1b) used to pass DC bias is 15 μH; the capacitor values (C in Fig 1b) to block the DC bias are 15 nF.

During 1H reception, the 1H signal is, (i) amplified by a 24 dB preamplifier (Advanced Receiver Research, Burlington, CT, USA), (ii) converted to 32.6 MHz using an RF mixer (ZAD-1, Mini-Circuit Inc., Brooklyn, NY) by mixing a 90.6 MHz sine wave from a precision frequency synthesizer (SG382, Stanford Research Systems, Sunnyvale, CA), which is synchronized using a 10 MHz clock signal from the host MRI system, and, (iii) filtered using a low-pass filter to pass the 32.6 MHz signal only (Fig. 1a). The frequency of the synthesizer is determined by subtracting the 23Na frequency from the 1H frequency, which is explained in Appendix A. The resultant 1H signal at the carrier frequency of 32.6 MHz is then (iv) fed into one of the 32Na receive channels20 of the MRI system.

Two custom-made 1H/23Na coils were used due to imaging samples with different dimensions. The first coil consists of a linear 23Na loop concentric with a linear 1H loop26 (Fig. 2a) on a 133 mm diameter tube, with the loops decoupled from each other using passive resonant traps (Fig. 2a). A second coil designed for knee imaging consists of a quadrature 23Na coil (a central circular loop that is spatially decoupled with an overlapped butterfly loop) and 1H linear coil (a butterfly loop spatially decoupled with the 23Na loops) (Fig. 2b).

Pulse Sequence

A dual-nuclei MRI pulse sequence (Fig. 3) was developed to manipulate both spin systems within the same pulse sequence, using the manufacturer’s pulse sequence development software (IDEA, Siemens Medical Solution, Erlangen, Germany). Sodium is selected as the main measurement nucleus and 1H as the second transmit nucleus.

Fig. 3.

Pulse sequence diagram for synchronous GRE imaging of 23Na and1H. Although the two frequencies share gradients, they are received on separate channels. RF and gradient pulses for 1H imaging are applied prior to the 23Na excitation RF pulse. All phase-encoding gradients are rewound (Grw) just before the acquisition of the phase reference echo. The 1H gradients before the 23Na pulse do not affect the 23Na signal, so that the 1H slice and phase encodes can be independent from 23Na slice and phase encodes. The method shown was used for both Cartesian and radial sampling. The phase reference pulse did not occur during GRE imaging, as there was sufficient 1H signal to enable phase correction without a reference pulse.

Synchronous 1H/23Na imaging was performed with a standard gradient-echo sequence (GRE) for 23Na with both 1H and 23Na transmit and receive occurring in the same sequence (Fig. 3). RF and gradient pulses for 1H imaging are added prior to the 23Na excitation RF pulse, so that the pulse sequence for 23Na imaging is not altered. The zeroth moment of the gradient pulses for 23Na slice-selection is compensated in the refocusing gradient of the 1H slice-selection. Sampling for both 1H and 23Na at the carrier frequency of 32.6 MHz was acquired simultaneously on two 23Na channels.

The pulse sequence in Fig. 3 had different k-space trajectories for either Cartesian or radial synchronous acquisition. During Cartesian acquisition, the sequence acquired a phase reference echo that is used to correct phase errors on the 1H Cartesian FIDs, as detailed later.

MRI Experiments

SMI was implemented for 3D Cartesian and 3D ultra-short TE (UTE) radial 1H/23Na-GRE. The Cartesian studies were performed to test SMI feasibility and SNR changes with a phantom. The radial studies tested in vivo image quality on a healthy human knee. The acquisition parameters are listed in Table I.

TABLE I.

Acquisition Parameters

| Column Name | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure | 4a,b | 5a | 4(c,)d,5b | 4,5,6a–f | 7a | 7b | 7c,d |

| Sample | Phantom | Phantom | Phantom | Phantom w/ MnCl |

Knee | Knee | Knee |

| Nuclei | 1H | 23Na | 1H/23Na | 1H/23Na | 1H | 23Na | 1H/23Na |

| Sampling | Cartesian | Cartesian | Cartesian | Cartesian | Radial | Radial | Radial |

| Coil | Quad | Quad | Quad | Linear | Quad | Quad | Quad |

| TR (ms) | 50 | 50 | 50/50 | 50/50 | 40 | 40 | 40/40 |

| TE (ms) | 9.51 | 2.45 | 9.51/2.45 | 7.27/2.25 | 0.70 | 0.27 | 0.70/0.27 |

| Flip Angle | 25 | 70 | 25/70 | 25°/70° | 25° | 70° | 25°/70° |

| FOV (mm) | 125 | 500 | 125/500 | 118/448 | 105 | 400 | 105/400 |

| Voxel Size (mm3) | 0.98 iso | 3.9 iso | 0.98/3.9 iso | 0.9/3.5 iso | 0.8 iso | 3.1 iso | 0.8/3.1 iso |

| Averages | 10 | 10 | (1) 10 | 5/5 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Acq. Matrix | 256×128×16 | 256×128×16 | 256×128×16 | 256×128×40 | 256×10240 | 256×10240 | 256×10240 |

| Image Time | 17 min | 17 min | 17 min | 21 min | 7 min | 7 min | 7 min |

| Readout Sampling | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 6/8 | - | - | - |

Acquisition parameters for the single and synchronous dual-nuclear GRE images shown in this paper. When two values are listed in a box, the first parameter is for the 1H parameters and the second for 23Na parameters in the pulse sequence.

The Cartesian phantom SMI studies were conducted with the linear and quadrature coil (Fig. 2) on a phantom that contains three cylindrical tubes with different concentrations of MnCl2 and NaCl (0.4 mM MnCl2 and 300 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM MnCl2 and 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM MnCl2 and 75 mM NaCl). Air surrounded the tubes when the quadrature coil was used, while liquid surrounded the tubes containing 0.2 mM MnCl2 and no NaCl during the experiment with the linear coil. The phantom study parameters are listed in Table IA–D.

Three sets of a healthy human knee images were acquired with 3D UTE radial sampling: a single-nuclear 1H acquisition, a single-nuclear 23Na acquisition, and a synchronous 1H/23Na acquisition. Radial SMI data was acquired with the quadrature coil (Fig. 2b) that conformed to the knee geometry. Imaging was conducted after informed consent and with approval of the local institutional review board.

For both Cartesian and radial studies, identical acquisition parameters (Table IA–C, IE–G) for each nucleus were used to compare single-nuclear imaging (SNI) and SMI image quality.

Post-processing Using Phase Reference Echoes:

Although the external synthesizer is synchronized with the host MRI system using a 10 MHz reference signal, the single stage mixing introduces a systematic and incremental phase-error into the 1H channel data, which may be due to the small difference in the frequency resolution between the scanner’s synthesizer and the mixer’s synthesizer. These small differences can be introduced during separate scan sessions when the sampling frequencies may occur after scanner calibration. For Cartesian imaging, this systematic phase-error is corrected using the 1H phase reference echoes after gradient rewinding (Grw in Figure 3), which are simultaneously acquired with each 23Na FID. Note that the 23Na phase reference echo is not useful for phase error correction because of its low SNR.

In order to correct this phase offset, the 1H image data is transferred to and processed on an offline computer. For each 1H imaging echo, the systematic phase error, θ, is estimated at the peak of the 1H phase reference echo during Cartesian imaging or by the first data point of each radial line, and subtracted from the 1H imaging echo by multiplying by .27,28 Offline reconstruction of the 1H radial data was done with a nearest-neighbor regridding algorithm, programmed using the Numpy package in Python programming language (Version 2.7, Python Software Foundation, https://www.python.org/). Nearest-neighbor was used due to the efficiency of implementation.

The single-nuclear 1H data was reconstructed using the same off-line reconstruction software for accurate comparison with the SMI 1H images. The single-nuclear 1H images were also constructed with and without phase correction to verify that the phase-correction process did not adversely affect 1H image quality. H image quality.

The 23Na data is reconstructed by the scanner for all images, as the additional 23Na hardware does not affect the scanner’s ability to reconstruct 23Na SNI or SMI radial data. The percent SNR difference is reported as the absolute value of the phase corrected image subtracted from the uncorrected image, all divided by the uncorrected image, and multiplied by 100. The SNRs were normalized by the noise along a similar region of image-space in registered images.

RESULTS

Synchronous 1H and 23Na images were obtained in both a phantom and in vivo (Figs. 4–7).

Fig. 4.

(a,b) Single-nuclear and (c,d) synchronously acquired proton images using Cartesian GRE reconstructed (a,c) without and (b,d) with phase correction from the reference echo. The images in (c,d) were obtained synchronously with sodium images in Fig. 5. (e) The SNR difference is shown between a registered single-nuclear image and phase-corrected synchronous image shows less than 10% SNR difference in the phantoms.

Fig. 7.

Single-nuclear (a,b) and synchronous multinuclear (c,d) knee images of a healthy volunteer. (a) and (b) were obtained in two 7 minute acquisitions for a total of a 14 minute scan time to acquire both nuclear images. (c) and (d) were obtained in a single 7 minute acquisition to obtain both nuclear images. The structure at the right of the proton images (a,c) is a plastic coil element that is visible because of the ultra-short TE acquisition.

Phantom Studies

Phase correction

The magnitude of a single-nuclear proton acquisition without and with phase correction is shown in Figs. 4(a) and 4(b), respectively. The percent difference between the single-nuclear data with and without phase correction was less than 10^(−9), which is near the precision error of the computer.

Phantom Proton Results

The proton data acquired synchronously with the sodium data without and with phase correction is shown in Figs. 4(c) and 4(d), respectively. Only the first average is shown in Fig. 4(c), as all ten averages would create a less coherent image. The proton image has significant artifact Fig. 4(c) that is removed with phase correction as shown in Fig. 4(d).

The synchronous data was shifted by 11 voxels in the readout direction and by 5 pixels in the phase-encode direction when compared to the single-nuclear data. After adjusting for image registration, the percent SNR difference, shown in Fig. 4(e), was 9±3% when measured over a similar region in either of the two brightest phantoms.

The data here demonstrates the effects of phase correction and the SNR difference using the different methods, although the proton images in Fig. 4 show susceptibility artifact.

Phantom Sodium Results

The sodium images acquired using both single-nuclear and synchronous acquisitions are shown in Figs. 5(a) and 5(b), respectively. The SNR difference is shown in Fig. 5(c), which is 6±3% as measured in the phantom.

Fig. 5.

(a) Single-nuclear and (b) synchronously acquired sodium images using Cartesian GRE. The sodium image in (b) was obtained synchronously with proton images in Fig. 4. (c) The SNR difference is shown between the shifted, registered single-nuclear image and the phase-corrected synchronous data shows less than 6% SNR difference in the phantoms. The full reconstructed sodium FOV is shown here, which is 3.8 times smaller than the proton FOV.

The image shown in 5(b) was acquired in the same acquisition as the image shown in 4(d), demonstrating the ability to acquire both proton and sodium data together for an overall reduced scan time. The full FOV is shown in Fig. 5(b), which is 3.8 times larger than the proton FOV. Because the 1H and 23Na signals are acquired using the same gradients for readout and phase-encoding, the 1H image data has a 3.8 times higher resolution and smaller FOV due to the ratio of the 1H and 23Na gyromagnetic ratios (= γ1H /γ23Na).

A much better phantom image is shown in Fig. 6, which sampled k-space more fully and had MnCl2 surrounding the tubes to reduce susceptibility artifact. This image was not acquired with the same SNR comparisons. The full FOV is shown in the 1H images in all planes in Fig. 6, while the sodium images were interpolated and reduced to a similar FOV.

Fig. 6.

(a-c) Proton and (d-f) sodium SMI images acquired during a single synchronous 21-minute 3D GRE Cartesian acquisition. Three orthogonal slices from a full 3D data set are shown for both (a-c) proton and (d-f) sodium images. Images are shown at the same physical scale showing the entire 1H FOV and ¼ of the 23Na FOV.

In Vivo Human Knee Study

Fig. 7 shows images from single-nuclear and synchronous 1H/23Na multi-nuclear radial acquisitions in a healthy human knee. The single-nuclear 1H and 23Na images were acquired in two 7-minute acquisitions, respectively, for a total acquisition time of 14 minutes. The synchronous 1H/23Na images were acquired in a single 7-minute acquisition, i.e., a total acquisition time of 7 minutes.

There were < 0.1% SNR differences between the 1H-SNI acquisition with and without phase correction, indicating that using phase correction of radial data by subtracting each k-space readout from its first data point remains accurate.

The SNR was similar for the synchronous and single-nuclear 23Na acquisitions. The 1H synchronous in vivo images had a ~ 6% SNR decrease when compared to the single-nuclear 1H images.

Both SNI and SMI 1H show the plastic structure that the coils were mounted on as a halo around the object. There is undersampling artifact in the lower portion of the knee image (Figs. 7(a,c)).

DISCUSSION

The overall result of this study is that both 1H and 23Na images were acquired in a single acquisition, demonstrating a novel method to acquire MRI/NMR data from an additional second nucleus without an increase of acquisition time, with minor to no loss (~ 6%) in 23Na-SNR and minor losses (~ 9%) in 1H-SNR. Without modification such as the method we presented, SMI would not have been possible on our system. This is similar to an approach used by Meyerspeer22 This study demonstrates a method for the substantial reduction of acquisition time for acquiring image data from both nuclear species. Typical single-nuclear acquisitions of both 1H and 23Na would require twice the acquisition time for two sequential acquisitions. As one of the major limitations of in vivo 23Na-MRI is its long acquisition time, SMI may greatly improve the practical applications of 23Na-MRI3–11,13,17,22, without requiring additional acquisition time. By acquiring both 1H and 23Na within the same readout, TRs can be kept low for efficient imaging. With future developments, SMI could make 23Na more attractive for clinical imaging by allowing it to be acquired simultaneously without impacting imaging times.

Our solution for SMI was performed without modifying the internal components of our MRI scanner by adding hardware to our non-proton setup, requiring an additional TR switch, a mixer, a frequency synthesizer, and a synchronous multi-nuclear pulse sequence. This work did not involve acquiring or transmitting both the 1H/23Na signals simultaneously, and therefore did not require significant scanner modifications required by previous work18. Our method relies on the unmodified scanner hardware for reception of both nuclear species, by down-converting and receiving the 1H signal through a second sodium channel. Interleaved methods that use software-defined switching of the RF amplifier and receiver frequencies were not possible here, so a modification to commercial hardware was required. This method could be permanently implemented within the system by modifying RF receive channel pathways. In this respect our implementation of SMI was different from previously described setups that modified internal system components14–16,18–21,23.

The introduction of SMI resulted in minor losses to the 1H-SNR (~ 9%) and minor losses (~ 6%) to 23Na-SNR. The 23Na signal pathways and sequence did not change, even with the introduction of SMI. Sufficient SNR was obtained to illustrate the benefits of obtaining simultaneous data from two nuclei in the same sequence, reducing the need for two separate imaging sessions. We attribute the minor losses on the 1H images during SMI (~10%) due to using a separate add-on preamplifier, from the possible introduction of noise in the mixing process, and from the very minor change in k-space acquisition. This work suggests that many 1H sequences could implement 1H/23Na-SMI without degradation of 1H imaging ability and obtain 23Na imaging data without image acquisition time cost.

We demonstrated that correcting data with a phase reference acquisition at the center of k-space allows the data to be reconstructed with near zero errors in a single-nuclear phantom experiment.

We demonstrated SMI with two k-space trajectories using similar GRE pulses, for an SNR comparison using Cartesian acquisition and for efficient 23Na sampling for in vivo imaging. This is a demonstration of 23Na SMI with truly simultaneous radial acquisition for obtaining high quality 23Na images.

Completely interleaved imaging allows more flexible sequences, such that the proton sequences could be nearly completely independent from the sodium sequences. However, truly simultaneous imaging offers the ability to reduce the readout time and TRs due to combined sampling.

As a result of simultaneous 1H/23Na acquisition, the 23Na-FOV is 3.8 times larger than the 1H-FOV, and the 1H voxel size is 3.8 times smaller than the 23Na resolution. Currently, our MRI system limits our FOV to a maximum of 500 mm, which means that the largest 1H-FOV that can be acquired without aliasing is 130 mm during down-sampled SMI. This FOV is sufficient for imaging moderate sized knees and breasts, or imaging with FOV-limiting local coils, but would require implementation of 1H slice selection or increased oversampling for imaging larger FOVs. This restriction is primarily software-related, as standard MRI systems have a much broader range of selectable FOVs that make use of higher gradient strengths than we used here. However, the difference in FOVs can be very practical and useful, as 1H imaging occurs at a typically higher resolution than 23Na imaging due to 23Na-SNR being much lower than the 1H-SNR. Increasing the 23Na-FOV by a factor of four doubles 23Na-SNR compared to the original FOV. The constraint on the ratio of 23Na to 1H FOV and resolution thus fits very naturally into the requirement for 23Na imaging to increase its SNR through use of larger voxel sizes than 1H imaging.

Although the current work has demonstrated flexibility in the selection of imaging parameters, some parameters must be identical using this setup, such as receiver bandwidth and FOV-ratio, because both NMR signals are simultaneously sampled within the same acquisition window. The FOVs can be completely independent by applying additional gradients prior to 23Na excitation, which adds or subtracts the phase-encoding gradient appropriate for the 1H-FOV. In addition, by using a 1H pulse before the 23Na pulse, accurate slice selection of the 1H data would be possible that could not occur with simultaneous 1H/23Na pulses. The restriction in other imaging parameters may be completely removed by interleaving the acquisitions between two nuclei with a minor cost in time efficiency.

In our current implementation, we use two of the 23Na receive channels of our MRI system. One channel receives the 23Na signal directly from a 23Na coil, while a second channel receives the 1H signal mixed down to the 23Na frequency. The SNR of the 23Na images can also be improved by the use of a 23Na phased array coil, as demonstrated in26, without any change to the SMI system. B1 maps of the coil for accurate 23Na quantitation could be acquired by altering the 23Na flip angle29 during SMI, without changing the 1H flip angle. It is also straightforward to acquire 1H/23Na-SMI data with multiple 1H channels, by duplicating the conversion box including the switching circuitry in Fig 1b.

The current mixing scheme for 1H-data in the receive data caused a consistent non-random phase error along the increasing FID numbers. This systematic phase-error was small as the synthesizer frequency is set to match the down-converted 1H signal to the carrier frequency. The systematic phase-error caused by down-conversion was straightforward to estimate and correct using the 1H phase reference signal during the post-processing. A higher performance synthesizer would result in reduced phase errors but would result in additional cost.

During the lengthy acquisitions that often occur for 23Na imaging, the subject may move, reducing the quality of 23Na data. In SMI, the 1H phase reference FID could be used to correct the phase error in 23Na FIDs that may be induced by motion, which is not possible using 23Na FIDs alone due to 23Na’s low intrinsic SNR. 1H/23Na-FID data with severe motion corruption subject’s motion can be identified using the 1H-FID and excluded from processing. By using this 1H phase reference echo in real-time self-gated 23Na-MRI, the phase and magnitude of the phase reference echo peak could be calculated and then compared to those of the reference echoes to determine if the 23Na and 1H imaging echoes are corrupted by the subject’s motion, which then would be rejected and reacquired30. This method requires accurate estimation of the systematic phase increment. The specific absorption rate (SAR) was calculated automatically by the scanner, using predetermined values in the coil-control files. The sequences used in this study were not pulse intensive and so did not result in SAR limitations of TR or flip angle. SMI implementations with other types of sequences (eg. turbo-spin echo) would have to consider SAR limitations more fully.

Our synchronous technique could be extended to study the NMR characteristics of other nuclei (13C, 19F, 31P), as well as extended to triple-nuclear imaging21 by converting and receiving multiple frequencies to a single frequency, provided that the scanner allows transmit on more than two frequencies in a sequence.

CONCLUSIONS

We have demonstrated synchronous 1H and 23Na MRI using an unmodified commercial scanner with multinuclear capability and additional hardware. We have shown in vivo synchronous acquisition of 1H and 23Na images of the knee in a 7 minute scan time, which is nearly equivalent to acquiring 1H and 23Na images with two separate conventional single-nuclear 7 minute scans. We have demonstrated the acquisition of synchronous 1H and 23Na GRE images with simultaneous Cartesian and simultaneous radial sampling, with a low and equal TR for both sodium and proton acquisitions. Our method allows the addition of 23Na imaging to conventional 1H imaging with little or no increase in total scan time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partly supported by NARSAD Independent Investigator Grants, NSF CBET 1133908, VA Merit Review Grant, Margolis Foundation, NMSS Research Grant NMSS RG 5233-A-2, NIH Research Grant R01-EB002524.

APPENDIX

A. Phase relationship during mixing

The mixer acts as a frequency multiplier between the 1H MR signal with a time-varying phase θH(t) and the synthesizer signal with an initial phase θSo:

| (1) |

After low-pass filtering, the converted signal becomes,

| (2) |

Equation (1) indicates that the new mixed frequency will be

| (3) |

Equation (2) also indicates that the converted 1H signal retains the same phase θH(t) as in the original 1H signal added to the synthesizer phase θSo, and the 1H signal is also modulated by the amplitude of the reference signal.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rooney WD, Springer CS. 1991. The molecular environment of intracellular sodium: 23Na NMR relaxation. NMR in Biomedicine;4(5):227–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weast RC, Astle MJ, Beyer WH. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics: CRC press Boca Raton, FL; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouwerkerk R, Bleich KB, Gillen JS, Pomper MG, Bottomley PA. 2003. Tissue sodium concentration in human brain tumors as measured with 23Na MR imaging. Radiology;227(2):529–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ouwerkerk R, Jacobs MA, Macura KJ, Wolff AC, Stearns V, Mezban SD, Khouri NF, Bluemke DA, Bottomley PA. 2007. Elevated tissue sodium concentration in malignant breast lesions detected with non-invasive 23Na MRI. Breast Cancer Res Treat;106(2):151–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borthakur A, Shapiro EM, Beers J, Kudchodkar S, Kneeland JB, Reddy R. 2000. Sensitivity of MRI to proteoglycan depletion in cartilage: comparison of sodium and proton MRI. Osteoarthr Cartilage;8(4):288–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy R, Insko EK, Noyszewski EA, Dandora R, Kneeland JB, Leigh JS. 1998. Sodium MRI of human articular cartilage in vivo. Magn Reson Med;39(5):697–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borthakur A, Shapiro EM, Akella SV, Gougoutas A, Kneeland JB, Reddy R. 2002. Quantifying sodium in the human wrist in vivo by using MR imaging. Radiology;224(2):598–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wheaton AJ, Borthakur A, Shapiro EM, Regatte RR, Akella SV, Kneeland JB, Reddy R. 2004. Proteoglycan loss in human knee cartilage: quantitation with sodium MR imaging--feasibility study. Radiology;231(3):900–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maril N, Rosen Y, Reynolds GH, Ivanishev A, Ngo L, Lenkinski RE. 2006. Sodium MRI of the human kidney at 3 Tesla. Magn Reson Med;56(6):1229–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen Y, Lenkinski RE. 2009. Sodium MRI of a human transplanted kidney. Acad Radiol;16(7):886–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thulborn KR, Davis D, Snyder J, Yonas H, Kassam A. 2005. Sodium MR imaging of acute and subacute stroke for assessment of tissue viability. Neuroimaging Clin N Am;15(3):639–53, xi-xii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neumaier‐Probst E, Konstandin S, Ssozi J, Groden C, Hennerici M, Schad LR, Fatar M. 2015. A double‐tuned 1H/23Na resonator allows 1H‐guided 23Na‐MRI in ischemic stroke patients in one session. International Journal of Stroke;10(A100):56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inglese M, Madelin G, Oesingmann N, Babb JS, Wu W, Stoeckel B, Herbert J, Johnson G. 2010. Brain tissue sodium concentration in multiple sclerosis: a sodium imaging study at 3 tesla. Brain;133(Pt 3):847–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SW, Hilal SK, Cho ZH. 1986. A multinuclear magnetic resonance imaging technique--simultaneous proton and sodium imaging. Magn Reson Imaging;4(4):343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stehning C, Keupp J, Rahmer J. Simultaneous 23Na/1H Imaging with Dual Excitation and Double Tuned Birdcage Coil. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med; 2011. p 1501. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaggie JD, Sapkota N, Jeong K, Shi X, Morrell GR, Bangerter NK, Jeong E-K. Synchronous 1H and 23Na dual-nuclear MRI on a clinical MRI system, equipped with a time-shared second transmit channel Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med;2014; Milan, Italy: p 1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruin PW, Koken P, Versluis MJ, Aussenhofer SA, Meulenbelt I, Börnert P, Webb AG. 2015. Time‐efficient interleaved human 23Na and 1H data acquisition at 7 T. NMR in Biomedicine;28(10):1228–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keupp J, Rahmer J, Grässlin I, Mazurkewitz PC, Schaeffter T, Lanza GM, Wickline SA, Caruthers SD. 2011. Simultaneous dual-nuclei imaging for motion corrected detection and quantification of 19F imaging agents. Magn Reson Med;66(4):1116–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wild JM, Ajraoui S, Deppe MH, Parnell SR, Marshall H, Parra-Robles J, Ireland RH. 2011. Synchronous acquisition of hyperpolarised 3He and 1H MR images of the lungs - maximising mutual anatomical and functional information. NMR Biomed;24(2):130–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeong E, Sapkota N, Kaggie J, Shi X. 2013. Simultaneous Dual-Nuclear 31P/1H MRS at a clinical MRI system with time-sharing second RF channel. Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med;21:2781. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wild JM, Marshall H, Xu X, Norquay G, Parnell SR, Clemence M, Griffiths PD, Parra-Robles J. 2013. Simultaneous imaging of lung structure and function with triple-nuclear hybrid MR imaging. Radiology;267(1):251–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyerspeer M, Magill AW, Kuehne A, Gruetter R, Moser E, Schmid AI. 2015. Simultaneous and interleaved acquisition of NMR signals from different nuclei with a clinical MRI scanner. Magn Reson Med; doi 10.1002/mrm.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schnall MD, Bolinger L, Renshaw PF, Haselgrove JC, Subramanian VH, Eleff SM, Barlow C, Leigh JS, Chance B. 1987. Multinuclear MR imaging: a technique for combined anatomic and physiologic studies. Radiology;162(3):863–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Bruin PW, Versluis MJ, Koken P, Aussenhofer SA, Meulenbelt I, Börnert P, Webb AG. Time-efficient interleaved 23Na and 1H acquisition at 7T Milan, Italy: Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med; 2014. p 0034. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boada FE, Gillen JS, Shen GX, Chang SY, Thulborn KR. 1997. Fast three dimensional sodium imaging. Magn Reson Med;37(5):706–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaggie JD, Hadley JR, Badal J, Campbell JR, Park DJ, Parker DL, Morrell G, Newbould RD, Wood AF, Bangerter NK. 2013. A 3 T sodium and proton composite array breast coil. Magn Reson Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klose U 1990. In vivo proton spectroscopy in presence of eddy currents. Magn Reson Med;14(1):26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helms G, Piringer A. 2001. Restoration of motion-related signal loss and line-shape deterioration of proton MR spectra using the residual water as intrinsic reference. Magn Reson Med;46(2):395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allen SP, Morrell GR, Peterson B, Park D, Gold GE, Kaggie JD, Bangerter NK. 2011. Phase‐sensitive sodium B1 mapping. Magnetic resonance in medicine;65(4):1125–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi X, Kim SE, Kholmovski E, Parker D, Jeong EK. 2009. Improvement of Accuracy of Diffusion MRI using Real-Time 2D Self-Gated Data Acquisition. NMR Biomed;22(5):545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]