Supplemental Digital Content is Available in the Text.

Keywords: access to health care, ambulatory care–sensitive conditions, diabetes, Medicaid, Medicaid expansion

Abstract

Among nonelderly adults with diabetes, we compared hospitalizations for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions from 2013 (pre-Medicaid expansion) and 2014 (post-Medicaid expansion) for 13 expansion and 4 nonexpansion states using State Inpatient Databases. Medicaid expansion was associated with decreases in proportions of hospitalizations for chronic conditions (difference between 2014 and 2013 −0.17 percentage points in expansion and 0.37 in nonexpansion states, P = .04), specifically diabetes short-term complications (difference between 2014 and 2013 −0.05 percentage points in expansion and 0.21 in nonexpansion states, P = .04). Increased access to care through Medicaid expansion may improve disease management in nonelderly adults with diabetes.

IN 2015, an estimated 9.4% of the overall US population (30.3 million people), and 6% of the 18- to 64-year-old population, had diabetes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). Low-income (≤138% of federal poverty level) nonelderly adults are disproportionately affected; diabetes prevalence was 13.4% among individuals who receive health care coverage through a government-subsidized program (including Medicaid) compared with 4.6% among the privately insured (American Diabetes Association, 2013). In this population, insurance coverage is fundamental to ensure access to care and the opportunity to manage this disease: lack of insurance coverage has been associated with poor diabetes management (Zhang et al., 2012). This has considerable consequences in terms of health and economic burden. Diabetes is expensive: health care costs in 2012 were estimated at $327 billion, with $71.1 billion spent specifically for hospitalizations (American Diabetes Association, 2018). Some of these hospitalizations can be avoided with appropriate access to care and better disease management. Diabetes is among the most common ambulatory care–sensitive conditions (ACSCs), that is, those conditions that can be managed through high-quality preventive care and treatment and for which expensive events such as hospitalizations for diabetes complications can be avoided (Bindman et al., 2008).

Medicaid expansion in 2014 created the opportunity for more low-income nonelderly adults to be insured in some states (Kaufman et al., 2015). Providing more individuals with Medicaid coverage could increase access to ambulatory care, potentially improve diabetes management, reduce preventable diabetes complications, and reduce the number of hospitalizations. In the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, a trial that randomly assigned Medicaid coverage through a lottery system, Medicaid was associated with a higher proportion of diabetes diagnoses and increased use of diabetes medications (Baicker et al., 2013). The Medicaid expansion was also associated with increases in diabetes screening and glucose testing along with increases in the proportion of Medicaid-insured adults diagnosed with diabetes (Kaufman et al., 2015; Sommers et al., 2016). Both Medicaid coverage and expansion have been associated with improved access to care and diabetes management as evidenced by a higher number of ambulatory care visits than those for uninsured populations (Christopher et al., 2016; Miller & Wherry, 2017). Currently, it is not clear whether the increased access to care resulting from the Medicaid expansion may have led to reduced ACSC hospitalizations among people with diabetes.

To address this knowledge gap, we compared 2013 and 2014 hospital discharge data for nonelderly adults with diabetes in 17 US states of which 13 had expanded Medicaid. We hypothesized that the Medicaid expansion would be associated with lower proportions of hospitalizations of uninsured patients and lower proportions of ACSC hospitalizations for uncontrolled diabetes, diabetes short-term complications, diabetes long-term complications, heart failure, hypertension, as well as acute and chronic composite conditions (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2015).

METHODS

This study consists of a retrospective analysis of 2013-2014 hospital discharge data for adults with diabetes. Data are summarized and compared by states that expanded and did not expand Medicaid. To examine how these states may differ, we obtained state population characteristics from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Data source and study populations

Health Care Costs and Utilization Project's State Inpatient Databases

Hospital discharge data were obtained from the Health Care Costs and Utilization Project's State Inpatient Databases (HCUP-SID) (AHRQ, n.d.). Data on all inpatient hospital discharges for 2013 and 2014 were obtained for 13 states in HCUP-SID that expanded their Medicaid program under the Affordable Care Act (Arizona, Colorado, Iowa, Kentucky, Michigan, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, and West Virginia) and 4 that did not (Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Wisconsin). Thirty states were excluded because data for the pre- and postexpansion years were not available when we began the study. Three expansion states with complete data (Hawaii, Nebraska, and South Dakota) were excluded because they had small populations and very high costs to acquire the data.

From the 17 selected states, we identified all hospital discharges for persons between the ages of 18 and 64 years where any of the diagnosis codes associated with the hospital stay included a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (see Table A in the Supplemental Material, available at: http://links.lww.com/JACM/A86). The final data set included 759 992 hospitalizations in 2013 and 765 990 hospitalizations in 2014 in expansion states and 526 867 hospitalizations in 2013 and 539 878 hospitalizations in 2014 in nonexpansion states.

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

Populations in the selected states were described using data from the BRFSS, which surveys the noninstitutionalized adult population in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. BRFSS survey weights account for the sampling scheme and nonresponse bias. Additional details about the BRFSS survey methodology can be found elsewhere (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). We used the BRFSS data to describe and compare the expansion and nonexpansion states because of their comprehensive nature; public health data are available for all states. We examined the data for nonelderly adult BRFSS respondents (aged 18-64 years) from years 2013 and 2014. The final data set included 210 353 respondents from the selected 13 expansion and 4 nonexpansion states.

Study outcomes

The outcomes of interest were the state proportion of total diabetes-related hospitalizations by insurance status (Medicaid, uninsured/self-paying, other insurance) and by ACSCs (Niefeld et al., 2003). ACSC hospitalizations were those with primary discharge diagnosis codes for uncontrolled diabetes, diabetes short-term complications, diabetes long-term complications, heart failure, and hypertension. These were identified using the AHRQ-formulated Prevention Quality Indicators (PQIs) framework. The PQIs are a set of indicators of quality and health care access in the community setting (AHRQ, 2015). We also obtained acute composite ACSCs, which included dehydration, bacterial pneumonia, and urinary tract infection, and the chronic composite ACSCs, which included diabetes short- and long-term complications, hypertension, heart failure, uncontrolled diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and asthma. The diagnosis codes we used are listed in Table B in the Supplemental Material (available at: http://links.lww.com/JACM/A86).

State demographics

From the BRFSS data, using BRFSS survey weights, we calculated the proportion of the state population by gender, race/ethnicity, age group, marital status, education, employment status, and annual household incomes. Furthermore, we obtained the proportion of the population in fair or poor health, as well as the proportion of the population that self-reported a diagnosis of diabetes, angina, or coronary disease or a history of myocardial infarction or stroke.

Statistical analysis

State demographics were compared by expansion status using the BRFSS data. We used the HCUP-SID data to compare the proportions of hospitalizations by insurance status and by preventable ACSCs between expansion and nonexpansion states for each year. For each state, we calculated the differences between 2013 and 2014 in the proportions of hospitalizations by insurance status and for each ACSC of interest. Then, we calculated the average differences separately for expansion and nonexpansion states. Finally, we compared these average differences in the proportions of hospitalizations by insurance status and for the ACSCs between expansion and nonexpansion states using t tests to determine statistical significance. Data management was conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina), and statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 14.2 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

The population in expansion states was more likely to be white and less likely to be black, to have annual household income of less than $25 000, and to have diabetes, compared with the population in nonexpansion states (Table). Expansion and nonexpansion states were similar on other demographics.

Table. Characteristics of Nonelderly Adults in Selected States by Medicaid Expansion Status, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

| Characteristics | Expansion Statesa | Nonexpansion Statesb |

|---|---|---|

| Population, n | ||

| Unweighted | 155 601 | 54 752 |

| Weighted | 92 209 552 | 55 716 192 |

| Female, % | 50.1 | 50.5 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 65.8 | 59.5 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 9.2 | 19.4 |

| Hispanic, any race | 16.0 | 16.0 |

| Other | 9.0 | 5.1 |

| Age, % | ||

| 18-29 y | 26.1 | 25.8 |

| 30-39 y | 20.5 | 20.0 |

| 40-49 y | 20.5 | 21.0 |

| 50-64 y | 32.9 | 33.2 |

| Married, % | 50.2 | 49.7 |

| Education, % | ||

| Did not graduate high school | 13.3 | 14.1 |

| High school graduate | 27.2 | 29.3 |

| Some college or college graduate | 59.5 | 56.6 |

| Employment status, % | ||

| Employed | 65.8 | 64.9 |

| Unemployed | 8.5 | 9.1 |

| Out of the workforce | 25.7 | 26.0 |

| Annual household income, % | ||

| <$25 000 | 24.3 | 27.9 |

| ≥$25 000 | 61.9 | 58.6 |

| Missing/refused | 13.8 | 13.5 |

| Fair/poor self-reported health, % | 15.6 | 16.9 |

| Self-reported diagnoses, % | ||

| Diabetes | 7.0 | 7.8 |

| Angina or coronary heart disease | 2.5 | 2.7 |

| History of myocardial infarction or stroke | 3.9 | 4.6 |

aArizona, Colorado, Iowa, Kentucky, Michigan, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, and West Virginia.

bFlorida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Wisconsin.

In 2013, about 22% and 7% of diabetes-related hospitalizations in expansion states were among Medicaid beneficiaries and uninsured patients, respectively, compared with about 20% and 10%, respectively, in nonexpansion states. Expansion and nonexpansion states had similar proportions of hospitalizations for ACSCs: these were less than 1% for uncontrolled diabetes and hypertension, and about 5% for diabetes short- and long-term complications. The proportion of hospitalizations with a heart failure diagnosis was higher in nonexpansion states (4.3%) than in expansion states (3.4%). Overall, about 9% of diabetes-related hospitalizations were for acute composite ACSCs and 19% for the chronic composite ACSCs (see Table C in the Supplemental Material, available at: http://links.lww.com/JACM/A86).

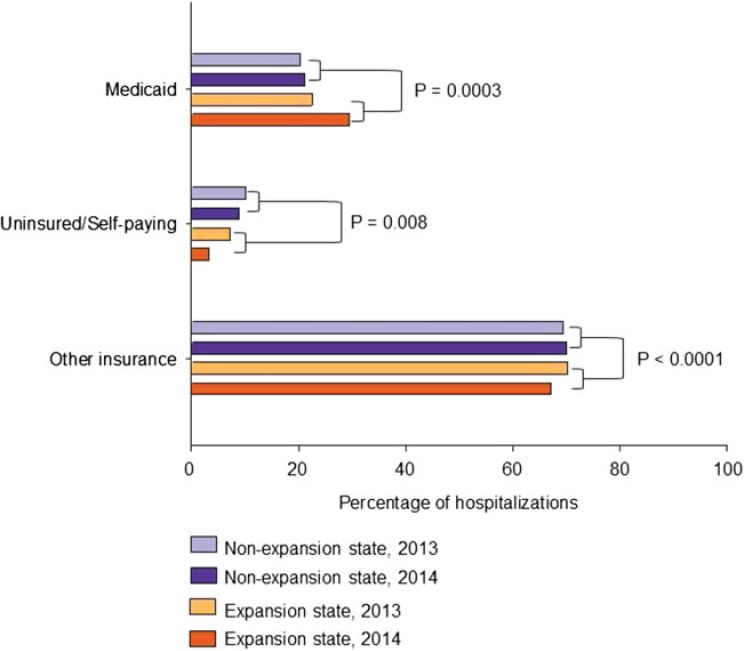

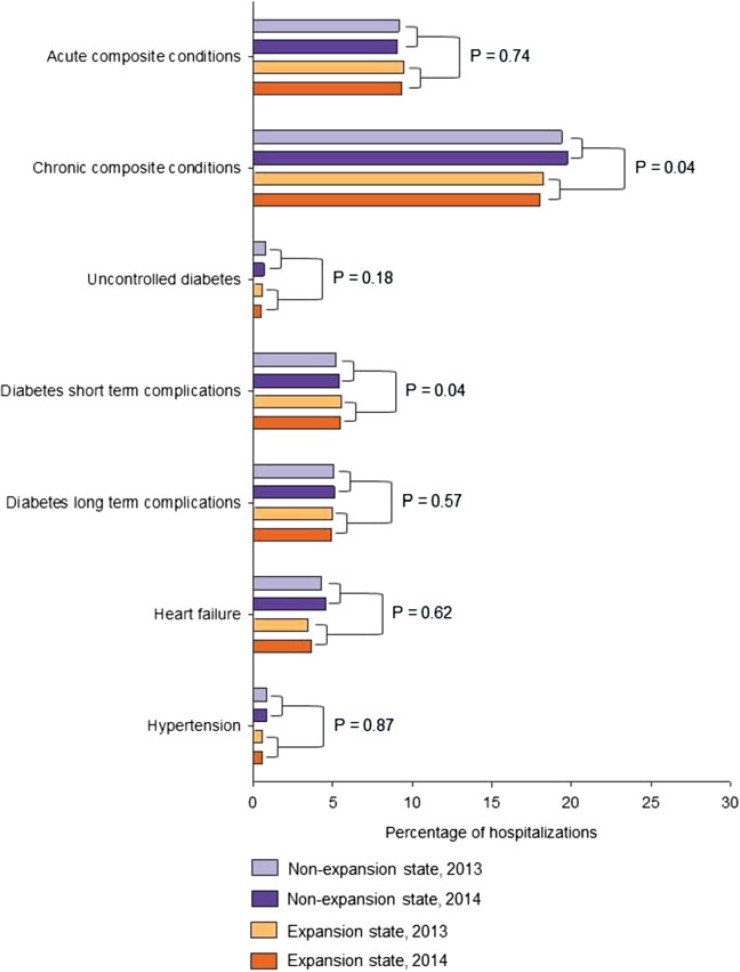

Medicaid expansion was associated with an increase in the proportion of hospitalizations that were Medicaid covered (difference between 2014 and 2013 was 7.04 percentage points [PP] in expansion states and 0.74 in nonexpansion states, P = .0003) and a decrease in the proportion of hospitalizations for uninsured/self-paying patients (difference between 2014 and 2013 was −4.01 PP in expansion states and −1.36 in nonexpansion states, P = .0008) (see Table C in the Supplemental Material, available at: http://links.lww.com/JACM/A86, and Figure 1). Medicaid expansion was associated with decreases in the proportion of hospitalizations for chronic composite ACSCs (difference between 2014 and 2013 was −0.17 PP in expansion states and 0.37 in nonexpansion states, P = .04) and specifically for diabetes short-term complications (difference between 2014 and 2013 was −0.05 PP in expansion states and 0.21 in nonexpansion states, P = .04) (see Table C in the Supplemental Material, available at: http://links.lww.com/JACM/A86, and Figure 2). Medicaid expansion was not associated with a statistically significant difference in the proportions of hospitalizations for other ACSCs examined (see Table C in the Supplemental Material, available at: http://links.lww.com/JACM/A86, and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Proportions of hospitalizations by insurance status among adults aged 18 to 64 years with diabetes in selected Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states before (2013) and after expansion (2014), Health Care Costs and Utilization Project State Inpatient Databases.

Figure 2.

Proportions of hospitalizations for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions among adults aged 18 to 64 years with diabetes in selected Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states before (2013) and after expansion (2014), Health Care Costs and Utilization Project State Inpatient Databases.

DISCUSSION

The current study found that in comparison with nonexpansion states, there was a statistically significant increase in the proportion of hospitalizations covered by Medicaid (∼34 000 admissions) and a reduction in the proportion of uninsured/self-paying hospitalizations (∼14 000 admissions) in expansion states. The findings also showed that Medicaid expansion was associated with a statistically significant reduction in the proportions of ACSC hospitalizations for chronic conditions (∼2900 hospitalizations) and specifically for diabetes short-term complications (∼1400 hospitalizations annually). However, there were no changes in the proportions of hospitalizations for other ACSCs including uncontrolled diabetes and acute composite conditions associated with Medicaid expansion.

The findings of this study are consistent with those of prior studies on the effects of Medicaid coverage among adults with diabetes. Lack of insurance and disruptions in Medicaid coverage are associated with poor glycemic control among individuals with diabetes and higher rates of hospitalizations for ACSCs (Bindman et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2012). Medicaid expansion has been associated with increased access to care, increased rates of diabetes diagnoses, and increased use of diabetes medications, although not with receiving American Diabetes Association–defined clinical diabetes care services (glycated hemoglobin tests twice yearly, annual eye examination, annual foot examination, and annual influenza shot) (American Diabetes Association, 2017; Baicker et al., 2013; Luo et al., 2018; Miller & Wherry, 2017; Sommers et al., 2012). Compared with no medical insurance, Medicaid coverage was associated with having at least one annual ambulatory care visit; however, Medicaid coverage was not associated with diabetes awareness or control (Christopher et al., 2016). These studies and ours suggest that, overall, Medicaid expansion has an important impact on increased access to care and potentially a reduction in avoidable hospitalizations among nonelderly adults with diabetes. Moreover, Medicaid expansion may improve outcomes in other chronic diseases as indicated by the significant impact we found for the composite ACSCs, which included diabetes complications as well as heart failure, hypertension, COPD, and asthma. In other studies, Medicaid expansion was associated with a reduction in the proportions of hospitalizations for major cardiovascular events in expansion states compared with nonexpansion states (Akhabue et al., 2018) and a reduction in 1-year mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease who initiated dialysis (Swaminathan et al., 2018).

The observed reduction in the proportions of hospitalizations for chronic composite conditions and specifically for diabetes short-term complications in Medicaid expansion states compared with nonexpansion states suggests that increased access to ambulatory care through Medicaid expansion may have resulted in improved disease management and a decrease in ACSCs. Because the increase in the proportion of Medicaid hospitalizations was larger than the decrease in the proportion of uninsured/self-pay hospitalizations, these data also suggest that there is some spillover effect, as people who were previously covered by other insurance are now covered by Medicaid. However, the magnitude of the differences indicates that the larger effect was to move people from no coverage to Medicaid coverage.

The strengths of the current study include representative data from inpatient hospital discharge data for the states included in the analysis. The current study should also be interpreted in light of its limitations. The statistically significant reduction in the proportions of ACSC hospitalizations for chronic conditions and diabetes short-term complications may be driven by the increase in the proportion of hospitalizations for these conditions in nonexpansion states and the corresponding decrease in the proportions of hospitalizations in expansion states. Since we had data on a small number of nonexpansion states, it is possible that the increase in the proportions of hospitalizations in nonexpansion states may be due to unknown events aside from Medicaid expansion that affected the outcome differentially between expansion and nonexpansion states over time. The use of ICD-9 (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision) codes to identify participants with the conditions of interest provides less detailed information than clinical data. In addition, we may have missed admissions for people with diabetes for whom a diagnosis code for diabetes was not listed in the discharge data. However, this should not be an extensive problem since diabetes is an important comorbidity that could affect the amount the hospital is paid for treating the patient. Furthermore, it is unlikely that the frequency of omitted codes would differ systematically in 2013 and 2014. The period of observation may have been too short to observe significant associations, especially between Medicaid expansion and the proportions of hospitalizations for uncontrolled diabetes and acute composite conditions. It is also possible that some of the differences observed between the expansion and nonexpansion states are due to the population of the nonexpansion states being largely southern, with the exception of Wisconsin. In comparison, the expansion states were largely nonsouthern. However, because our primary analysis compared within-state changes over time, it is unlikely that this would have a significant impact on the results. The current study had limited statistical power to detect an association between Medicaid expansion and the change in the proportion of hospitalizations for uncontrolled diabetes and acute composite conditions, as these diagnoses had a low overall prevalence in this population (Amin et al., 2014; Bergamin & Kiosoglous, 2017; Stookey et al., 2005). Data were not available for all US states, which may limit generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, we did not have data on ambulatory care utilization. It is possible that our assumption that Medicaid expansion increases ambulatory care utilization, which then results in a decrease in proportions of hospitalizations for diabetes-related ACSCs, may not be correct.

CONCLUSION

Medicaid expansion was associated with a decrease in the proportion of hospitalizations for chronic composite conditions and specifically for diabetes short-term complications among nonelderly adults with diabetes. This suggests that increased access to care through Medicaid expansion may improve disease management among people with diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

†Deceased October 17, 2018.

Author Contributions: F.L.M. contributed to the design of the study and wrote the manuscript. M.L.K. (deceased) contributed to the conception and design of the study, analyzed the HCUP-SID data, wrote part of the methods section, provided expertise on Medicaid expansion, and revised prior drafts of the manuscript for intellectually important content. J.P.S. analyzed the BRFSS data, wrote part of the methods section, and revised the manuscript for intellectually important content. E.B.L. contributed to the conception and design of the study, provided expertise on the analysis plan, and revised the manuscript for intellectually important content. L.H. contributed to the analysis of the HCUP-SID data and revised the manuscript for intellectually important content. K.R.R. contributed to the design of the study, provided expertise on the analysis plan, and revised the manuscript for intellectually important content. M.P. contributed to the design of the study, provided expertise on the analysis plan, and revised the manuscript for intellectually important content. Y.L. contributed to the design of the study and revised the manuscript for intellectually important content. J.M.B. provided expertise on the analysis plan, contributed to the design of the study, and revised the manuscript for intellectually important content. A.A. contributed to the design of the study and revised the manuscript for intellectually important content. A.L.C. contributed to the conception and design of the study, provided expertise on diabetes, led the study team, and revised the manuscript for intellectually important content. M.L.K. (deceased), L.H., and J.P.S. had full access to the data. L.H. and J.P.S. take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

All authors excluding M.L.K. (deceased) have approved the final article.

The study was supported by R18 DK109501 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. This work was also supported by American Heart Association Greater Southeast Affiliate Grant 16PRE29640015 (MONDESIR). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the American Heart Association.

M.L.K. (deceased) received research funding from Amgen. E.B.L receives research funding from Amgen, has consulted for Novartis, and has served on an advisory board for Amgen. A.L.C. receives research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim and is on the advisory board for Astra Zeneca. F.L.M., J.P.S., L.H., M.P., K.R.R, A.A., Y.L., and J.M.B. have no relationships to disclose.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (www.ambulatorycaremanagement.com).

REFERENCES

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2015). AHRQ Quality Indicators™—Prevention Quality Indicators (AHRQ Pub. No. 15-M053-3-EF). Retrieved from https://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/Downloads/Modules/PQI/V50/PQI_Brochure.pdf

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (n.d.). H-CUP databases. Retrieved August 7, 2017, from https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/databases.jsp

- Akhabue E., Pool L. R., Yancy C. W., Greenland P., Lloyd-Jones D. (2018). Association of state Medicaid expansion with rate of uninsured hospitalizations for major cardiovascular events, 2009–2014. JAMA Network Open, 1(4), e181296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association. (2013). Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care, 36(4), 1033–1046. 10.2337/dc12-2625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association. (2017). Standards of medical care in diabetes—2017. Diabetes Care, 40(Suppl. 1), S1–S135.27979885 [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association. (2018). Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2017. Diabetes Care, 41(5), 917–928. 10.2337/dci18-0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin A. N., Cerceo E. A., Deitelzweig S. B., Pile J. C., Rosenberg D. J., Sherman B. M. (2014). The hospitalist perspective on treatment of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia. Postgraduate Medicine, 126(2), 18–29. 10.3810/pgm.2014.03.2737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baicker K., Taubman S. L., Allen H. L., Bernstein M., Gruber J. H., Newhouse J. P. ... Oregon Health Study Group. (2013). The Oregon experiment—Effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. The New England Journal of Medicine, 368(18), 1713–1722. 10.1056/NEJMsa1212321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamin P. A., Kiosoglous A. J. (2017). Non-surgical management of recurrent urinary tract infections in women. Translational Andrology and Urology, 6(Suppl. 2), S142–S152. 10.21037/tau.2017.06.09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindman A. B., Chattopadhyay A., Auerback G. M. (2008). Interruptions in Medicaid coverage and risk for hospitalization for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions. Annals of Internal Medicine, 149(12), 854–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). The BRFSS data user guide. Atlanta, GA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). National diabetes statistics report: Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher A. S., McCormick D., Woolhandler S., Himmelstein D. U., Bor D. H., Wilper A. P. (2016). Access to care and chronic disease outcomes among Medicaid-insured persons versus the uninsured. American Journal of Public Health, 106(1), 63–69. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman H. W., Chen Z., Fonseca V. A., McPhaul M. J. (2015). Surge in newly identified diabetes among Medicaid patients in 2014 within Medicaid expansion states under the Affordable Care Act. Diabetes Care, 38(5), 833–837. 10.2337/dc14-2334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H., Chen Z. A., Xu L., Bell R. A. (2018). Health care access and receipt of clinical diabetes preventive care for working-age adults with diabetes in states with and without Medicaid expansion: Results from the 2013 and 2015 BRFSS. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. Advance online publication. 10.1097/phh.0000000000000832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S., Wherry L. R. (2017). Health and access to care during the first 2 years of the ACA Medicaid expansions. The New England Journal of Medicine, 376(10), 947–956. 10.1056/NEJMsa1612890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niefeld M., Braunstein J., Wu A., Saudek C., Weller W., Anderson G. (2003). Preventable hospitalization among elderly Medicare beneficiaries with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 26(5), 1344–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommers B. D., Baicker K., Epstein A. M. (2012). Mortality and access to care among adults after state Medicaid expansions. The New England Journal of Medicine, 367(11), 1025–1034. 10.1056/NEJMsa1202099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommers B. D., Blendon R. J., Orav E. J., Epstein A. M. (2016). Changes in utilization and health among low-income adults after Medicaid expansion or expanded private insurance. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(10), 1501–1509. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stookey J. D., Pieper C. F., Cohen H. J. (2005). Is the prevalence of dehydration among community-dwelling older adults really low? Informing current debate over the fluid recommendation for adults aged 70+ years. Public Health Nutrition, 8(8), 1275–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan S., Sommers B. D., Thorsness R., Mehrotra R., Lee Y., Trivedi A. N. (2018). Association of Medicaid expansion with 1-year mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease. JAMA, 320(21), 2242–2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Bullard K. M., Gregg E. W., Beckles G. L., Williams D. E., Barker L. E., Imperatore G. (2012). Access to health care and control of ABCs of diabetes. Diabetes Care, 35(7), 1566–1571. 10.2337/dc12-0081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.