Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Epigenetics play a significant role in brain pathologies. We currently evaluated the role of a recently discovered CNS-enriched epigenetic modification known as 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) in regulating transcriptomic and pathogenic mechanisms following focal ischemic injury.

Methods:

Young and aged male and female mice were subjected to transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) and the peri-infarct region was analyzed at various times of reperfusion. Two days prior to MCAO, siRNA against an isoform of the 5hmC producing enzyme ten-eleven translocase (TET) was injected intracerebrally. Ascorbate was injected intraperioneally (i.p.) at 5 min, 30 min, or 2 h reperfusion. Motor function was tested with rotorod and beam-walk test.

Results:

Focal ischemia rapidly induced the activity of ten-eleven translocase (TET), the enzyme that catalyzes the formation of 5hmC and preferentially increased expression of the TET3 isoform in the peri-infarct region of the ischemic cortex. Levels of 5hmC were increased in a TET3-dependent manner, and inhibition of TET3 led to wide-scale reductions in the post-ischemic expression of neuroprotective genes involved in antioxidant defense and DNA repair. TET3 knockdown in adult male and female mice further increased brain degeneration following focal ischemia, demonstrating a role for TET3 and 5hmC in endogenous protection against stroke. Ascorbate treatment following focal ischemia enhanced TET3 activity and 5hmC enrichment in the peri-infarct region. TET3 activation by ascorbate provided robust protection against ischemic injury in young and aged mice of both sexes. Moreover, ascorbate treatment improved motor function recovery in both male and female mice.

Conclusions:

Collectively, these results indicate the potential of TET3 and 5hmC as novel stroke therapeutic targets.

Keywords: Epigenetics, ascorbate, oxidative stress, neuroprotection, focal ischemia

INTRODUCTION

Ischemic stroke is a leading cause of both death and long-term disability in the adult population1. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying secondary brain damage after stroke are not yet completely understood which has limited the development of effective stroke therapies. Mounting evidence over the last two decades indicates that epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation and histone acetylation regulate gene expression and therefore significantly influence functional outcome after an ischemic injury2. In particular, DNA methylation (methylcytosine; 5mC) is known to suppress gene expression and exacerbate secondary brain damage after stroke3, 4. The TET isoforms (TET1-3) convert 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), which is a brain-enriched epigenetic modification that appears to derepress genes silenced by methylation5–7. TETs can further oxidize 5hmC to sequentially produce 5-fluorocytosine (5fC) and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC) modifications (Fig. 1A), which can be directly excised resulting in an unmethylated cytosine8–10. However, TET enzymes show substrate preference for 5mC making 5hmC less susceptible to further oxidation10, 11. Thus, formation of 5hmC has been identified as both a stable epigenetic modification and a mechanism for the demethylation of DNA.

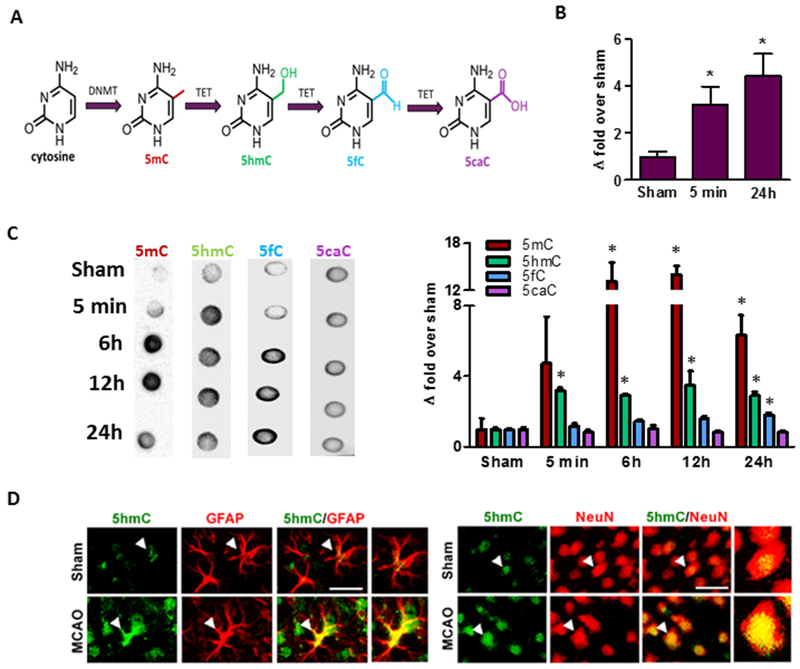

Fig. 1: Focal ischemia increased Tet activity and 5hmC levels in the cortical peri-infarct area.

The cytosine of DNA is converted to 5mC by isoforms of DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) and is sequentially oxidized to 5hmC, 5fC and 5caC by TETs (A). Transient MCAO in adult mice significantly increased TET activity at 5 min (n = 4/group) and 24 h (n = 5 to 8/group) of reperfusion (B) and increased levels of 5mC and 5hmC (C) between 6h to 24h of reperfusion compared to sham. 5fC was significantly induced at 24h of reperfusion, while 5caC levels did not change (C) (n = 4 to 5/group) *p<0.05. Increased 5hmC was localized in both neurons (NeuN+) and astrocytes (GFAP+) (C) in the peri-infarct area of the ischemic cortex at 24h reperfusion following transient MCAO (n = 3/group). Scale bars, 30 μm.

TETs and 5hmC have been shown to promote neuronal survival by enhancing the expression of protective genes under adverse conditions5, 12–14. Alterations in 5hmC patterning have been observed in several neurodegenerative diseases, but its specific role in these diseases is not clear15. In vitro studies from various cells lines have shown that hypoxic conditions lead to the induction of TET activity and increased global 5hmC levels16. Recent reports suggest that 5hmC and TETs may be associated with protecting endothelial and neuronal cells following vascular injury and hypoxic stress17–19. However, the role of 5hmC in the peri-infarct region (the region surrounding the irreversibly damaged core and capable of recovery) or as a therapeutic target in stroke has not been investigated. In the current study, we evaluated the molecular significance and therapeutic potential of 5hmC modulation in the post-stroke brain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Mice:

All animal protocols were approved by the Research Animal Resources and Care Committee of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and animals were cared for in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Publication 86-23, revised). Young adult male (12-13 weeks; 25-28g), young adult female (12-13 weeks; 18-21g), aged male (64-68 weeks; 35-40g) and aged female (64-68 weeks; 30-38g) C57Bl/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory) were used for experiments. Mice were housed with free access to chow and water in a pathogen-free environment.

Focal ischemia:

Focal ischemia was induced under isoflurane anesthesia by transient MCAO using the intraluminal suture method with a 6-0 silicon coated nylon monofilament (Doccol). The MCA was occluded for 60 min in young adult mice and 40 min in aged mice followed by reperfusion as described previously20. Regional cerebral blood flow and physiological parameters were monitored (pH, PaO2, PaCO2, hemoglobin, and blood glucose) and rectal temperature was maintained at 37.0°C. Cohorts of mice were euthanized under isoflurane anesthesia at various time points of reperfusion as needed by different experiments. In some experiments, ascorbate or saline (vehicle) was injected (500 mg/Kg; intraperitoneal; i.p.) at either 5 min, 30 min or 2 h of reperfusion following transient MCAO.

TET3 knockdown:

TET3 was knocked down by stereotaxic injection of a cocktail of three in vivo grade siRNAs targeting non-overlapping regions of TET3 (ThermoFisher Scientific; 8nmol in 3.2μl buffer + 0.8μl invivofectamine) into the cerebral cortex (from bregma −0.2 mm posterior, 1.5 mm dorsoventral and 3.0 mm lateral) at 0.5μl/min 48 h prior to MCAO as described previously21, 22. A non-targeting negative control siRNA was used as a control (ThermoFisher Scientific; 8nmol in 3.2μl buffer + 0.8μl invivofectamine) which had no effect on infarct size following MCAO (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Statistics:

Mann Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis test (Dunn’s post hoc) were used to compare differences between two groups or multiple groups, respectively. Repeated measures ANOVA (Sidak’s post hoc) was used to compare differences over time within the same group. Values shown are mean ± SEM and p<0.05 was used for significance cut-off. An investigator blinded to the study groups performed the histological and infarct analyses.

Additional materials/methods located in the Supplementary Information.

RESULTS

5hmC and TET3 are increased after stroke

Following transient MCAO in adult mice, TET activity was induced significantly at 5 min and remained sustained up to 24h of reperfusion in the peri-infarct cortex compared to sham (by 3.2- to 4.4-fold, respectively; p<0.05) (Fig. 1B). The peri-infarct area is highly susceptible to progressive necrosis following the initial injury, but is capable of recovery with treatment, and thus represents a major therapeutic target after stroke. DNA dot blot analyses showed significant induction of 5mC (by 6- to 13-fold; p<0.05) and 5hmC (by 3-fold; p<0.05) (Fig. 1C) between 5 min to 24 h reperfusion following transient MCAO compared to sham. Levels of 5fC were minimally increased (1.8-fold) at 24h reperfusion, while 5caC levels did not show any significant change after focal ischemia (Fig. 1C). Immunohistochemical analysis showed that 5hmC is colocalized with the neuronal nuclear antigen (NeuN; mature neuronal nuclear marker) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; astrocyte marker) in the peri-infarct cortex at 24h reperfusion following transient MCAO (Fig. 1D), although 5hmC was more abundant in the neuronal cells.

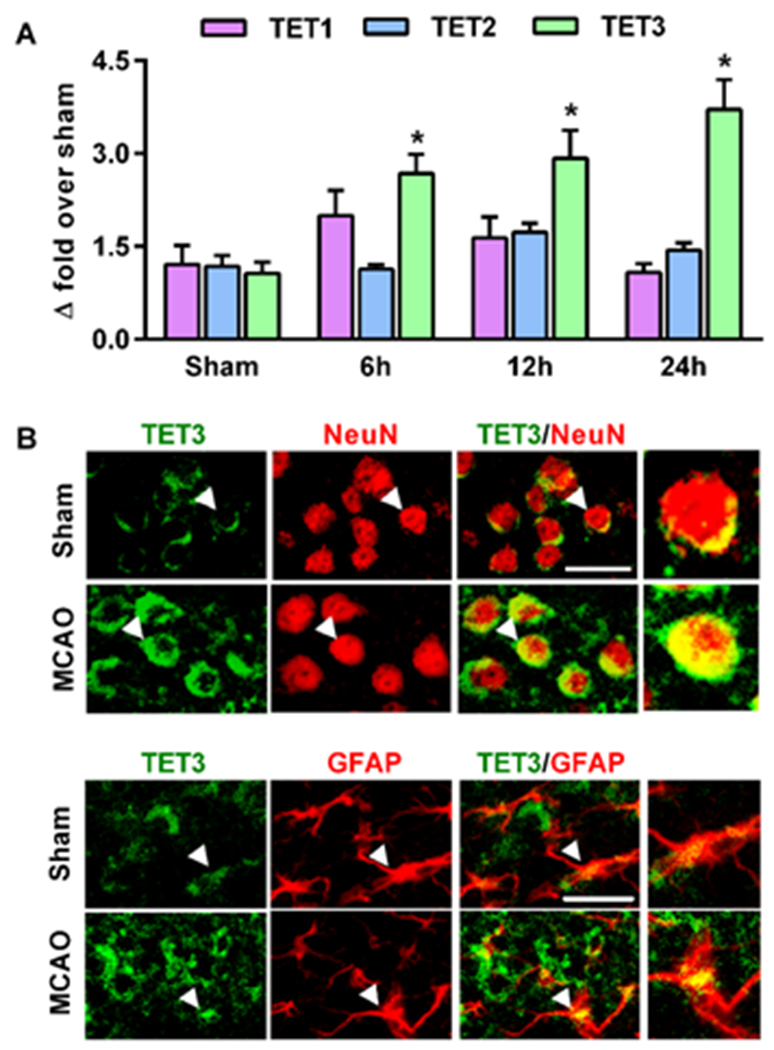

To evaluate whether changes in post-ischemic TET expression accompanied the increased levels of 5hmC and TET activity, we assessed expression of the three mammalian TET isoforms (TET1-3). TET3 mRNA levels increased significantly at 6h to 24h of reperfusion following transient MCAO compared to sham (by 2.7 to 3.7-fold; p<0.05), while TET1 and TET2 mRNA remained unaltered (Fig. 2A). Immunohistochemical analysis showed that the increased TET3 expression is localized in both NeuN+ neurons and GFAP+ astroglia of the peri-infarct cortex at 24h of reperfusion following transient MCAO compared to sham (Fig. 2B), although TET3 was more abundant in the neuronal cells.

Fig. 2: TET3 expression is increased following focal ischemia.

In mice subjected to transient MCAO, mRNA levels of TET3, but not TET1 and TET2, increased significantly compared to sham (A), *p<0.05. TET3 protein was colocalized in both neurons (NeuN+) (B) and astrocytes (GFAP+) (C) in the peri-infarct cortex. Scale bars, 30 μm.

TET3 knockdown decreased 5hmC levels and exacerbated ischemic brain damage

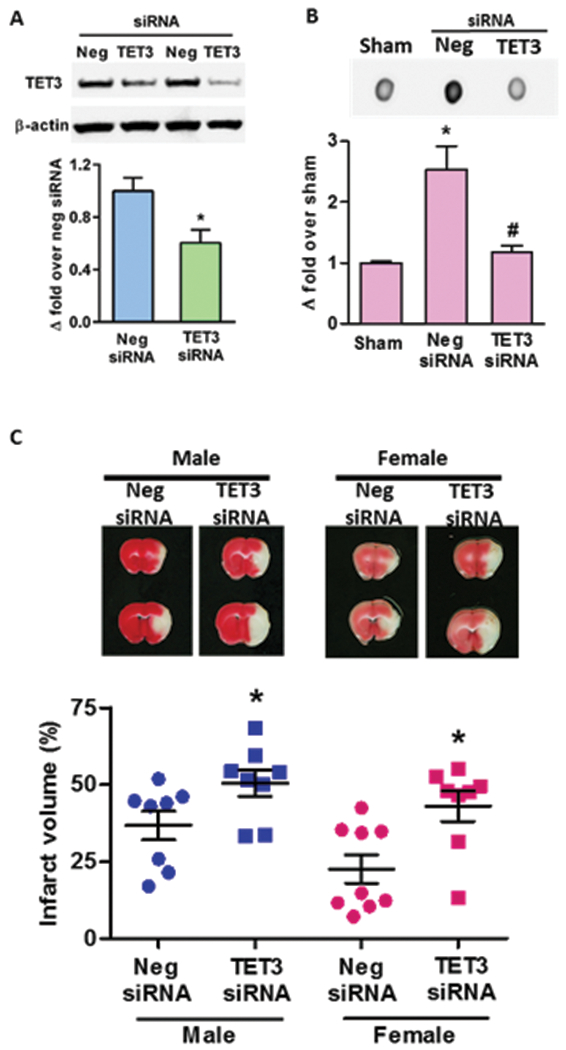

Since TET3 levels were increased in the peri-infarct cortex after focal ischemia, we determined whether TET3 is involved in regulating post-stroke 5hmC levels and secondary brain injury. Treatment with a TET3 siRNA cocktail two days prior to MCAO knocked-down TET3 protein in the ipsilateral cortex by 38% compared to negative control siRNA (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, TET3 mRNA levels were 73% lower in the TET3 siRNA treated mice compared to negative control siRNA treated mice at 6h of reperfusion following transient MCAO (Supplementary Fig. 2A). TET1 and TET2 mRNA were not affected by TET3 siRNA compared to negative control siRNA (Supplementary Fig. 2A). The mammalian TET3 exists in three isoforms due to alternative splicing. A full length TET3 (TET3-FL) that contains a DNA binding domain (CXXC), a short TET3 (TET3-s) which lacks the CXXC domain and a TET3-o that is exclusively expressed in oocytes during development23, 24. Both TET3-FL and TET3-s isoforms are known to be expressed predominantly in neurons and were observed to be reduced with TET3 siRNA treatment by 63% and 58%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2B).

Fig. 3: TET3 knockdown reduces 5hmC levels and aggravates secondary brain injury following transient MCAO.

Intracerebral injection of TET3 siRNA in adult mice significantly reduced the cortical TET3 protein levels at 2 days after treatment compared with negative control siRNA (Neg siRNA)-treated cohort (n = 3) (A). TET3 siRNA treatment decreased infarct size in mice of both sexes subjected to transient MCAO and 1 day of reperfusion (C). TTC-stained serial brain sections are from representative mice of each group (n = 8 to 9/group). *p<0.05 compared to sham and #p<0.05 compared to Neg siRNA.

DNA Dot blot analyses showed that 5hmC in the peri-infarct cortex was decreased by 54% in TET3 siRNA group compared to negative control siRNA group at 6h of reperfusion (Fig. 3B), demonstrating that TET3 is a major regulator of 5hmC in the peri-infarct cortex after focal ischemia. To assess the role of TET3 and 5hmC on ischemic brain damage, we subjected cohorts of mice to transient MCAO following treatment with either TET3 siRNA or negative control siRNA. The TET3 siRNA treated male and female mice exhibited exacerbated infarction (by 37% and 90%, respectively; p<0.05) compared to sex-matched negative control siRNA treated cohorts at 1 day of reperfusion following transient MCAO (Fig. 3C). This demonstrates the importance of TET3 as an endogenous neuroprotective mechanism against ischemic injury. There was no significant difference in mortality at 1 day of reperfusion between TET3 siRNA and negative control siRNA groups (Supplementary Fig. 3).

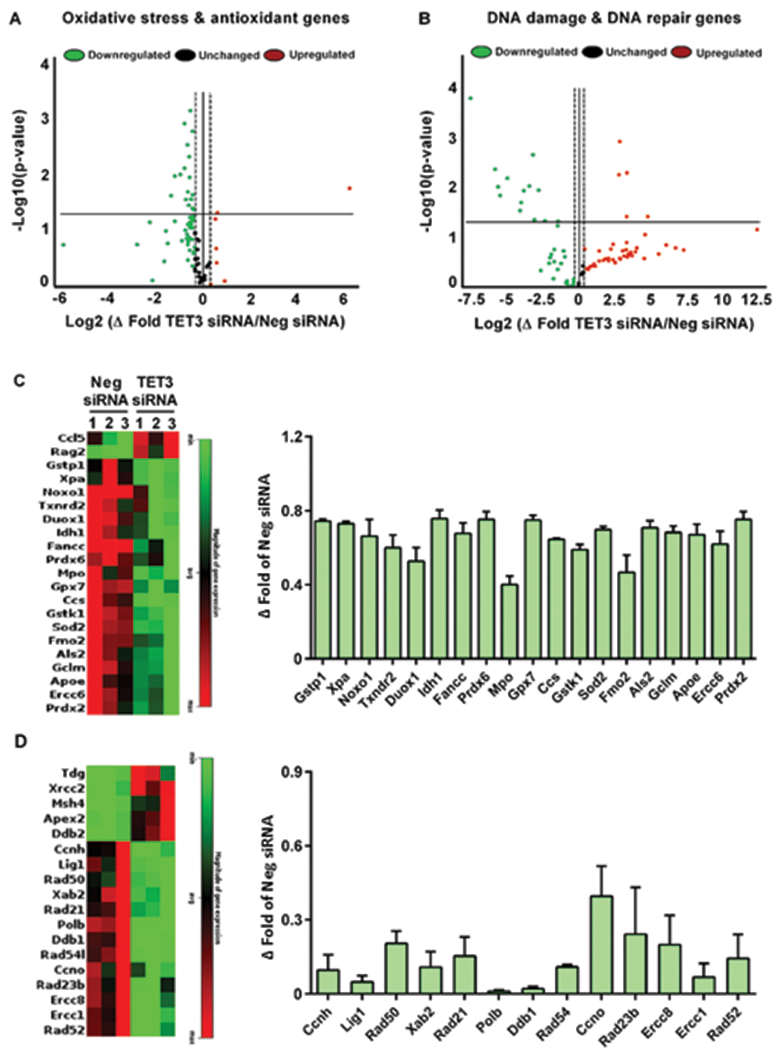

5hmC controls the post-ischemic expression of antioxidant and DNA repair genes

The 5hmC modification has been previously shown to be associated with the expression of protective genes in the brain13, 18. In particular, 5hmC has been linked to pathways that modulate oxidative stress and DNA repair, which are major pathogenic mechanisms involved in stroke pathophysiology25, 26. Therefore, we examined whether TET3/5hmC is involved in regulating the expression of ischemia-responsive genes that relate to these mechanisms. We profiled 84 genes related to oxidative stress and 84 genes related to DNA damage in the peri-infarct cortical tissue at 6h of reperfusion following transient MCAO using PCR arrays. TET3 knockdown significantly altered the post-ischemic expression of 21 oxidative-stress related genes, of which 19 were decreased and two were increased compared to the negative control siRNA group (Fig. 4A and C). While two of the decreased genes myeloperoxidase (MPO) and NADPH oxidase organizer 1 (Noxo1) are involved in neurodegeneration, the majority of the rest such as the glutathione-related enzymes and superoxide dismutase 2 (Sod2), play roles in antioxidant defense and have been previously shown to protect the brain against oxidative stress (Supplementary Table 1). TET3 knockdown also significantly altered the post-ischemic expression 18 DNA damage-related genes, of which 13 were decreased and 5 were increased compare to negative control siRNA group (Fig. 4B and D). The downregulated genes, such as the RAD homologs are DNA repair genes are known to prevent neuronal death in response to stress (Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 4: TET3 knockdown reduced the post-ischemic expression of genes that protect against oxidative stress and DNA damage.

Mice treated with TET3 siRNA showed significant alterations in oxidative stress/antioxidant-related genes (A and C) and DNA damage/DNA repair-related genes (B and D) compared with Neg siRNA group at 6h of reperfusion following transient MCAO. All values in C and D are significant (*p<0.05) compared to the Neg siRNA group. Ccl5, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5; Rag2, recombination activating gene 2; Gstp1, glutathione S-transferase Pi 1; Xpa, xeroderma pigmentosum group A; Noxo1, NADPH oxidase organizer 1; Txnrd2, thioredoxin reductase 2, mitochondrial; Duox1, dual oxidase-1; Idh1, isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (NADP+); Fancc, Fanconi anemia, complementation group C; Prdx6, peroxiredoxin 6; Mpo, myeloperoxidase; Gpx7, glutathione peroxidase 7; Ccs, copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase; Gstk1, glutathione S-transferase kappa 1; Sod2, superoxide dismutase 2; Fmo2, flavin containing monooxygenase 2; Als2, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 2 (juvenile) homolog; Gclm, glutamate-cysteine ligase, modifier subunit; Apoe, apolipoprotein E; Ercc6, excision repair cross-complementing rodent repair deficiency, complementation group 6; Prdx2, peroxiredoxin 2; Tdg, thymine DNA glycosylase; Xrcc2, X-ray repair complementing defective repair in Chinese hamster cells 2; Msh4, MutShomolog 4 (E.coli); Apex2, apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 2; Ddb2, damage specific DNA binding protein 2; Ccnh, cyclin H; Lig1, ligase I; Rad50, RAD50 homolog; Xab2, XPA binding protein 2; Rad21, RAD21 homolog; Polb, polymerase (DNA-directed) beta; Ddb1, damage-specific DNA binding protein 1; Rad54l, RAD54 like; Ccno, cylcin O; Rad23b, RAD23b homolog; Ercc1,8; excision repair cross-complementing rodent repair deficiency, complementation group 1,8; Rad52, RAD52 homolog.

Ascorbate enhances TET3 activity and 5hmC levels after stroke

Ascorbate has been previously implicated as a potential therapeutic agent against various neurological disorders due to its antioxidant properties27. More recently, it has been shown that ascorbate acts as a TET cofactor and increases TET catalytic activity28. Ascorbate treatment (intraperitoneal; i.p.) at 5 min of reperfusion following transient MCAO increased TET activity at 6h reperfusion in the peri-infarct cortex beyond induction with MCAO alone, which was abrogated with TET3 knockdown (Fig. 5A). Ascorbate treatment also increased 5hmC levels beyond induction by MCAO alone at 1 day of reperfusion in a TET3-dependent manner (Fig. 5B). This indicates that ascorbate specifically increases 5hmC by inducing TET3 catalytic activity in the post-stroke cortex.

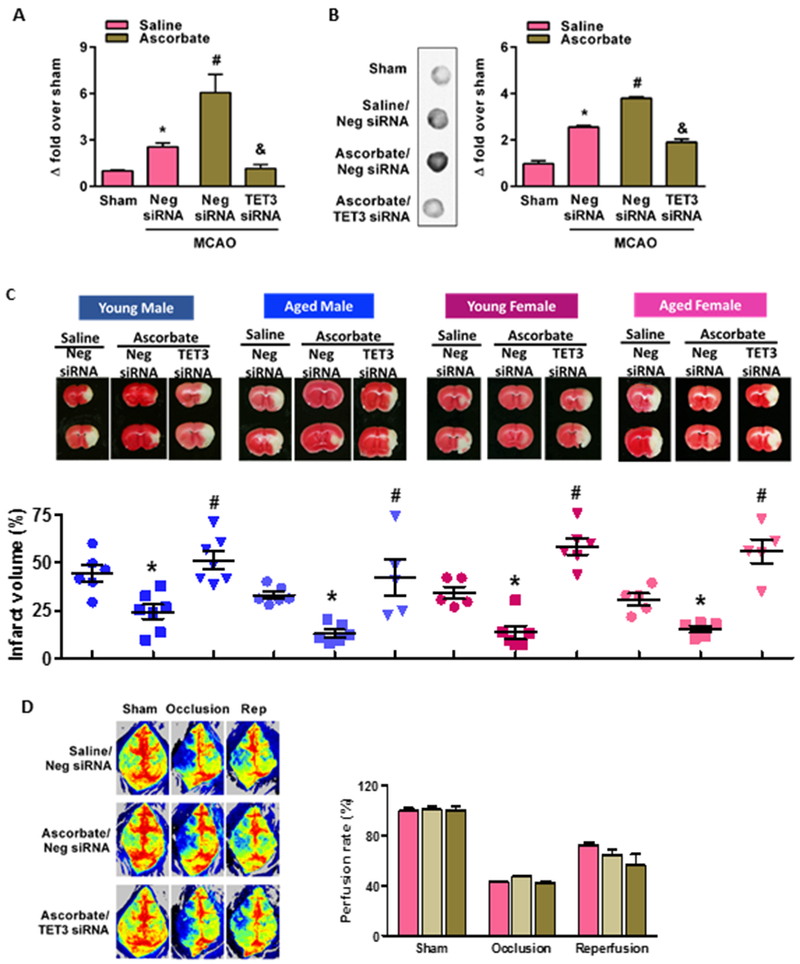

Fig. 5: Post-stroke ascorbate treatment increased TET3 activity and decreased infarction after focal ischemia.

Ascorbate (500 mg/Kg; i.p.) treatment significantly increased TET catalytic activity at 6 h reperfusion (A) and 5hmC levels at 24h reperfusion (B) compared with saline treated cohorts. TET3 siRNA treatment prevented post-ischemic ascorbate induced TET activity and 5hmC levels compared with negative control siRNA treated mice (A and B) (n = 5 to 8/group). *p<0.05 compared to sham/saline treatment, #p<0.05 compared to negative control siRNA/MCAO/saline treatment and &p<0.05 compared to negative control siRNA/MCAO/ascorbate treatment. Ascorbate treated young and aged male and female mice subjected to transient MCAO showed significantly smaller infarcts (C). Treatment with TET3 siRNA significantly prevented the ascorbate-induced neuroprotection compared to negative siRNA treated controls in both sexes and age groups. The TTC stained brain sections are from representative mice of each group (n = 5 to 7/group). *p<0.05 compared to neg siRNA/saline group and #p<0.05 compared to TET3 siRNA/ascorbate group. Laser speckle imaging showed that treatment with siRNA (TET3 or negative control) and/or ascorbate or saline had no significant effect on rCBF measured at baseline or during MCAO or at 24h reperfusion following transient MCAO in young adult male mice (D). The laser speckle images shown are from representative mice of each group (n = 3 to 4/group).

TET3 activation protects the brain after stroke

In both young and aged male and female mice, ascorbate treatment (i.p.) at 5 min of reperfusion following transient MCAO significantly decreased the infarct volume at 1 day of reperfusion compared to saline control (Fig. 5C). Importantly, treatment with TET3 siRNA abrogated the ascorbate-induced neuroprotection compared to negative control siRNA cohort in both sexes and at both ages (Fig. 5C). No effect of ascorbate treatment on mortality was observed at 1 day of reperfusion (Supplementary Fig. 4). This satisfies the Stroke Translational and Industry Roundtable (STAIR) criteria that stipulates preclinical therapeutic testing in both sexes, and more importantly in both young and aged animals subjected to stroke. As altered regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) can modulate ischemic brain damage, we confirmed that the neuroprotection afforded by ascorbate and its abrogation by TET3 knockdown is not due to altered rCBF either before or after MCAO, or during reperfusion (Fig. 5D).

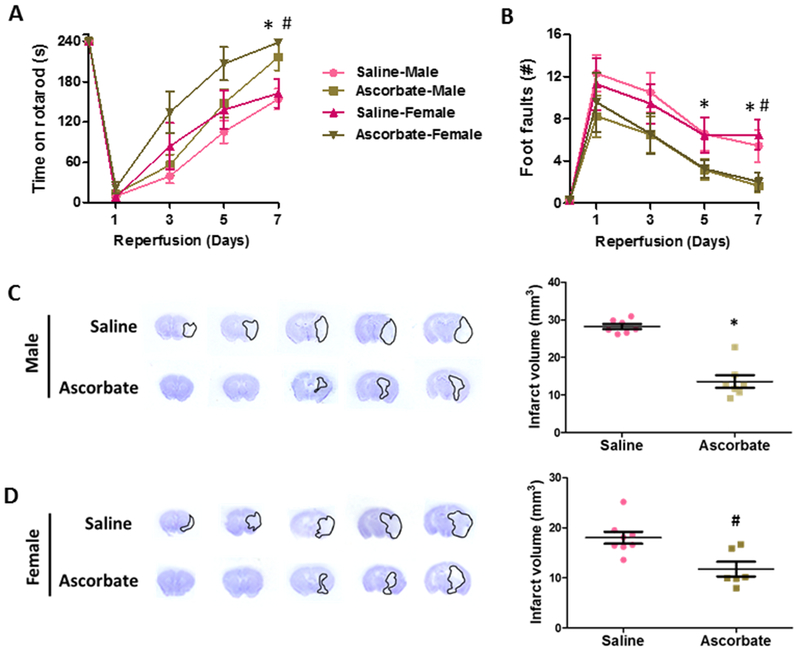

Delayed ascorbate treatment improved motor function recovery after transient MCAO

The above data showed that ascorbate treatment at 5 min of reperfusion following transient MCAO provided robust protection against ischemic injury at 24h reperfusion. Ascorbate treatment at 30 min or 2 h of reperfusion following transient MCAO also decreased infarct volume in young adult male mice compared to saline controls at 3 days of reperfusion (Supplementary Fig. 5 A and B). In order to determine whether delayed ascorbate treatment modulates functional recovery after focal ischemia, we treated a cohort of young adult male and female mice with ascorbate at 30 min reperfusion and tested motor function from 1 to 7 days of reperfusion. Ascorbate treatment significantly improved motor function recovery as identified by rotarod test (Fig. 6A) and beam-walk test (Fig. 6B) at 7 days of reperfusion compared with saline treated controls. As expected, in this cohort ascorbate treatment at 30 min of reperfusion also decreased infarction in both male and female mice estimated at 7 days of reperfusion (Fig. 6 C and D).

Fig. 6: Delayed ascorbate treatment promoted better motor function recovery.

Adult male and female mice treated with ascorbate (500 mg/Kg; i.p.) at 30 min of reperfusion following transient MCAO, showed significantly better motor function on rotarod test (A) and beam-walk test (B) and decreased infarct volume at 7 days of reperfusion compared to saline control (C,D). *p<0.05 in male mice # p<.05 in female mice.

DISCUSSION

TET3 was previously shown to play roles in neurodevelopment and maintenance of adult neuronal function26, 29, 30. However, the direct role of TET3 in neurological disorders, and more importantly conditions with acute brain damage was not assessed. We presently show that TET3 is a major regulator of 5hmC in the post-stroke brain and a putative mediator of endogenous protection against ischemic injury. Furthermore, we demonstrate that TET3 activation by ascorbate may be useful as a therapeutic intervention against focal ischemia.

Epigenetic modifications that mediate gene repression (i.e. DNA methylation, histone methylation, histone deacetylation) have been shown to regulate vascular mechanisms and pathways involved in neuronal survival following cerebral ischemia2. For example, previous studies showed that DNA methylation is robustly induced following focal ischemia3, 4, but treatment with DNMT inhibitors and demethylating agents decreased infarct volume and promoted functional recovery following transient MCAO4, 31. Similarly, pharmacological inhibition of histone deacetylases prevented neurodegeneration and improved functional outcome after focal ischemia32. The repressor element-1 silencing transcription factor (REST) mediates global gene repression by forming a complex with chromatin-modifying proteins that promote histone deacetylation of target genes33. We recently showed that REST knockdown de-represses neuroprotective genes and ameliorates ischemic brain injury22. Furthermore, disruption of REST scaffolding through inhibition of the lncRNA FosDT reduced infarct volume and improved motor function recovery after focal ischemia21. While epigenetic factors like DNA methylation involved in gene repression have been shown to worsen outcome after focal ischemia, this is the first study to show that therapeutic induction of DNA hydroxymethylation involved in stimulating gene expression is beneficial and promotes recovery after stroke.

The 5hmC modification was discovered several decades ago in bacteria34. However, 5hmC as an epigenetic mark has only been studied within the last 10 years with the discovery of high levels of 5hmC in the mammalian CNS and the identification of TET enzymes as mediators of the conversion of 5mC to 5hmC5, 7. Since then, 5hmC has been shown to be enriched at transcription factor binding sites, promoter regions and gene bodies, and is proposed to promote gene expression by modulating the accessibility of chromatin to transcriptional machinery35. 5hmC levels are known to be modulated temporally in embryonic stem cells and neural progenitor cells during various stages of CNS development36. Whereas in the mature brain, 5hmC can be regulated in a cell type-specific manner37. For example, in the CNS 5hmC modification is present at higher levels in neurons compared to astrocytes and microglia38. We observed that 5hmC is increased after stroke in both neurons and astrocytes, despite low levels of 5hmC staining in astrocytes. Interestingly, TETs show preference for 5mC, versus 5fC and 5caC, making 5hmC 10- to 100-fold more enriched than other oxidized methylcytosines10. The current study extrapolated this by showing robust upregulation of 5hmC levels compared to 5fC and 5caC levels after focal ischemia.

Hypoxic conditions have previously been shown to induce TET activity and increase global 5hmC levels16, 19. The 5hmC modification was shown to accumulate at canonical hypoxia response genes as well as hypoxia response elements that promote demethylation of DNA and hypoxia-inducible factor binding16. A previous study using a type-1 diabetic mouse model showed a significant decrease in global 5hmC levels in ischemic tissue after MCAO/reperfusion, but the role of 5hmC or TETs in protection or injury was not evaluated39. The differences observed in 5hmC enrichment following MCAO may be the result of the pathophysiological characteristics of the tissue area sampled (i.e. total hemisphere or ischemic core regions). In the current study, we focused on the peri-infarct region that contains viable ischemia-affected cells that are susceptible to subsequent cell death, but may be rescued by intervention. Vascular injury has been shown to result in reduced levels of 5hmC, but restoration of 5hmC diminished the pathogenic mechanisms including autophagy and inflammation17, 40. Similarly, intracerebral hemorrhage led to a global decrease in 5hmC and specifically reduced 5hmC in regulatory regions of known pro-survival genes18, indicating the therapeutic potential of 5hmC to protect brain after hemorrhagic stroke as well. Alterations in 5hmC levels have also been associated with pathways involved in neurodegenerative disorders such as Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease, but the specific role of 5hmC in these diseases is not yet understood15, 35, 41, 42.

TET3 is primarily found in neuronal cells23, 24 and has previously been shown to regulate pathways necessary for maintenance of cellular functions and stress-responsive pathways. For example, TET3 promotes a kinase-dependent DNA repair mechanism (Ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related) that is critical for maintaining genomic stability25. Knockdown of TET3 was shown to inhibit expression of genes important in the BER pathway of DNA repair23, 26. TET3 has also been implicated in hippocampal memory formation and is critical for appropriate glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the hippocampus26, 43. TET3 may also play a role in CNS regeneration as TET3 alters several genes involved in axon regeneration and retinal neurogenesis13, 44.

Ascorbate is an antioxidant and an enzyme cofactor that is known to reduce oxidative stress and thus protects the brain under adverse conditions27, 45, 46. Recent identification of ascorbate as an inducer of TET activity indicates its ability to modulate epigenetic regulation28, 47. Here, we show that TET3 is the major TET isoform targeted by ascorbate and that TET3 is critical for ascorbate-mediated protection against cerebral ischemia. Importantly, ascorbate treatment protected the brain even when treatment was delayed and also promoted better motor recovery after stroke. Due to its ability to act as an antioxidant and cofactor for other enzymes, ascorbate may also have TET3-independent roles in promoting neuroprotection. However, when TET3 was knocked-down, ascorbate-induced post-stroke neuroprotection was curtailed indicating that the major actions of ascorbate might be mediated by TET3 and 5hmC.

Epigenetics has revolutionized our understanding of the mechanisms involved in neurological disorders including post-stroke brain damage. The results of this study expand our knowledge in the molecular mechanisms regulating 5hmC and demonstrate that TET3 provides endogenous neuroprotection against cerebral ischemia. Furthermore, we identified that TET3/5hmC modulation can be developed as a stroke therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This study was funded in part by National Institute of Health grants R21 NS095192, R01 NS099531, R01 NS101960, R01 NS109459 and Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Wisconsin.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Authors declare no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Donnan GA, Fisher M, Macleod M, Davis SM. Stroke. Lancet. 2008;371:1612–1623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qureshi IA, Mehler MF. Emerging role of epigenetics in stroke: Part 1: Dna methylation and chromatin modifications. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:1316–1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Endres M, Meisel A, Biniszkiewicz D, Namura S, Prass K, Ruscher K, et al. Dna methyltransferase contributes to delayed ischemic brain injury. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3175–3181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Endres M, Fan G, Meisel A, Dirnagl U, Jaenisch R. Effects of cerebral ischemia in mice lacking dna methyltransferase 1 in post-mitotic neurons. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3763–3766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. The nuclear dna base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in purkinje neurons and the brain. Science. 2009;324:929–930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellen M, Ayata P, Dewell S, Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. Mecp2 binds to 5hmc enriched within active genes and accessible chromatin in the nervous system. Cell. 2012;151:1417–1430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian dna by mll partner tet1. Science. 2009;324:930–935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He YF, Li BZ, Li Z, Liu P, Wang Y, Tang Q, et al. Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by tdg in mammalian dna. Science. 2011;333:1303–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.An J, Rao A, Ko M. Tet family dioxygenases and dna demethylation in stem cells and cancers. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49:e323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ito S, Shen L, Dai Q, Wu SC, Collins LB, Swenberg JA, et al. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science. 2011;333:1300–1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu L, Lu J, Cheng J, Rao Q, Li Z, Hou H, et al. Structural insight into substrate preference for tet-mediated oxidation. Nature. 2015;527:118–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mi Y, Gao X, Dai J, Ma Y, Xu L, Jin W. A novel function of tet2 in cns: Sustaining neuronal survival. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:21846–21857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loh YE, Koemeter-Cox A, Finelli MJ, Shen L, Friedel RH, Zou H. Comprehensive mapping of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine epigenetic dynamics in axon regeneration. Epigenetics. 2017;12:77–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang H, Xu Z, Zhong P, Ren Y, Liang G, Schilling HA, et al. Cell cycle and p53 gate the direct conversion of human fibroblasts to dopaminergic neurons. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Mahdawi S, Virmouni SA, Pook MA. The emerging role of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in neurodegenerative diseases. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mariani CJ, Vasanthakumar A, Madzo J, Yesilkanal A, Bhagat T, Yu Y, et al. Tet1-mediated hydroxymethylation facilitates hypoxic gene induction in neuroblastoma. Cell Rep. 2014;7:1343–1352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng J, Yang Q, Li AF, Li RQ, Wang Z, Liu LS, et al. Tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2 inhibits atherosclerosis via upregulation of autophagy in apoe−/− mice. Oncotarget. 2016;7:76423–76436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang Y, Han S, Asakawa T, Luo Y, Han X, Xiao B, et al. Effects of intracerebral hemorrhage on 5-hydroxymethylcytosine modification in mouse brains. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:617–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miao Z, He Y, Xin N, Sun M, Chen L, Lin L, et al. Altering 5-hydroxymethylcytosine modification impacts ischemic brain injury. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:5855–5866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakka VP, Lang BT, Lenschow DJ, Zhang DE, Dempsey RJ, Vemuganti R. Increased cerebral protein isgylation after focal ischemia is neuroprotective. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:2375–2384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehta SL, Kim T, Vemuganti R. Long noncoding rna fosdt promotes ischemic brain injury by interacting with rest-associated chromatin-modifying proteins. J Neurosci. 2015;35:16443–16449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris-Blanco KC, Kim T, Bertogliat MJ, Mehta SL, Chokkalla AK, Vemuganti R. Inhibition of the epigenetic regulator rest ameliorates ischemic brain injury. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56:2542–2550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin SG, Zhang ZM, Dunwell TL, Harter MR, Wu X, Johnson J, et al. Tet3 reads 5-carboxylcytosine through its cxxc domain and is a potential guardian against neurodegeneration. Cell Rep. 2016;14:493–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu N, Wang M, Deng W, Schmidt CS, Qin W, Leonhardt H, et al. Intrinsic and extrinsic connections of tet3 dioxygenase with cxxc zinc finger modules. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang D, Wei S, Chen F, Zhang Y, Li J. Tet3-mediated dna oxidation promotes atr-dependent dna damage response. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:781–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu H, Su Y, Shin J, Zhong C, Guo JU, Weng YL, et al. Tet3 regulates synaptic transmission and homeostatic plasticity via dna oxidation and repair. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:836–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrison FE, May JM. Vitamin c function in the brain: Vital role of the ascorbate transporter svct2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:719–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minor EA, Court BL, Young JI, Wang G. Ascorbate induces ten-eleven translocation (tet) methylcytosine dioxygenase-mediated generation of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:13669–13674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li T, Yang D, Li J, Tang Y, Yang J, Le W. Critical role of tet3 in neural progenitor cell maintenance and terminal differentiation. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;51:142–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li X, Wei W, Zhao QY, Widagdo J, Baker-Andresen D, Flavell CR, et al. Neocortical tet3-mediated accumulation of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine promotes rapid behavioral adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:7120–7125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dock H, Theodorsson A, Theodorsson E. Dna methylation inhibitor zebularine confers stroke protection in ischemic rats. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6:296–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langley B, Brochier C, Rivieccio MA. Targeting histone deacetylases as a multifaceted approach to treat the diverse outcomes of stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:2899–2905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang Y, Myers SJ, Dingledine R. Transcriptional repression by rest: Recruitment of sin3a and histone deacetylase to neuronal genes. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:867–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wyatt GR, Cohen SS. A new pyrimidine base from bacteriophage nucleic acids. Nature. 1952;170:1072–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song CX, Szulwach KE, Fu Y, Dai Q, Yi C, Li X, et al. Selective chemical labeling reveals the genome-wide distribution of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:68–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan L, Xiong L, Xu W, Wu F, Huang N, Xu Y, et al. Genome-wide comparison of dna hydroxymethylation in mouse embryonic stem cells and neural progenitor cells by a new comparative hmedip-seq method. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nestor CE, Ottaviano R, Reddington J, Sproul D, Reinhardt D, Dunican D, et al. Tissue type is a major modifier of the 5-hydroxymethylcytosine content of human genes. Genome Res. 2012;22:467–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coppieters N, Dieriks BV, Lill C, Faull RL, Curtis MA, Dragunow M. Global changes in dna methylation and hydroxymethylation in alzheimer’s disease human brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:1334–1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalani A, Kamat PK, Tyagi N. Diabetic stroke severity: Epigenetic remodeling and neuronal, glial, and vascular dysfunction. Diabetes. 2015;64:4260–4271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu R, Jin Y, Tang WH, Qin L, Zhang X, Tellides G, et al. Ten-eleven translocation-2 (tet2) is a master regulator of smooth muscle cell plasticity. Circulation. 2013;128:2047–2057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villar-Menendez I, Blanch M, Tyebji S, Pereira-Veiga T, Albasanz JL, Martin M, et al. Increased 5-methylcytosine and decreased 5-hydroxymethylcytosine levels are associated with reduced striatal a2ar levels in huntington’s disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2013;15:295–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bernstein AI, Lin Y, Street RC, Lin L, Dai Q, Yu L, et al. 5-hydroxymethylation-associated epigenetic modifiers of alzheimer’s disease modulate tau-induced neurotoxicity. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25:2437–2450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kremer EA, Gaur N, Lee MA, Engmann O, Bohacek J, Mansuy IM. Interplay between tets and micrornas in the adult brain for memory formation. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seritrakul P, Gross JM. Tet-mediated dna hydroxymethylation regulates retinal neurogenesis by modulating cell-extrinsic signaling pathways. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allahtavakoli M, Amin F, Esmaeeli-Nadimi A, Shamsizadeh A, Kazemi-Arababadi M, Kennedy D. Ascorbic acid reduces the adverse effects of delayed administration of tissue plasminogen activator in a rat stroke model. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;117:335–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ranjan A, Theodore D, Haran RP, Chandy MJ. Ascorbic acid and focal cerebral ischaemia in a primate model. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1993;123:87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yin R, Mao SQ, Zhao B, Chong Z, Yang Y, Zhao C, et al. Ascorbic acid enhances tet-mediated 5-methylcytosine oxidation and promotes dna demethylation in mammals. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:10396–10403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.