Abstract

BACKGROUND:

In pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), right ventricular (RV) failure is the main cause of mortality. Non-invasive estimation of ventricular-vascular coupling ratio (VVCR), describing contractile response to afterload, could be a valuable tool for monitoring clinical course in children with PAH. This study aimed to test two hypotheses: VVCR by cardiac magnetic resonance (VVCRCMR) correlates with conventional VVCR by right heart catheterization (VVCRRHC) and both correlate with disease severity.

METHODS AND RESULTS:

Twenty-seven patients diagnosed with idiopathic and associated PAH without post-tricuspid shunt, who underwent RHC and CMR within 17 days at two specialized centers for paediatric PAH were retrospectively studied. Clinical functional status and hemodynamic data were collected. Median age at time of MRI was 14.3 years (IQR: 11.1–16.8), median PVRi 7.6 WU×m2 (IQR: 4.1–12.2), median mPAP 40 mmHg (IQR: 28–55) and median WHO-FC 2 (IQR: 2–3). VVCRCMR, defined as stroke volume/end-systolic volume ratio was compared to VVCRRHC by single-beat pressure method using correlation and Bland-Altman plots. VVCRCMR and VVCRRHC showed a strong correlation (r=0.83, p<0.001). VVCRCMR and VVCRRHC both correlated with clinical measures of disease severity (pulmonary vascular resistance index [PVRi], mean pulmonary artery pressure [mPAP], mean right atrial pressure [mRAP], and World Health Organization functional class [WHO-FC]; all p≤0.02).

CONCLUSIONS:

Non-invasively measured VVCRCMR is feasible in paediatric PAH and comparable to invasively assessed VVCRRHC. Both correlate with functional and haemodynamic measures of disease severity. The role of VVCR assessed by CMR and RHC in clinical decision-making and follow-up in paediatric PAH warrants further clinical investigation.

Keywords: paediatric pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular function, cardiac magnetic resonance, right heart catheterization, ventricular-vascular coupling ratio

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a progressive disease with high morbidity and mortality. PAH is characterized by remodelling of the pulmonary vasculature, leading to increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and artery pressure (PAP), and thus the afterload seen by the right ventricle (RV). When the increased afterload exceeds the RV adaptation capacity, progressive ventricular failure and eventual death in PAH will occur(1,2). Accordingly, parameters describing RV afterload or RV function and structure have been shown to be important indicators of disease severity and prognosis in PAH(3–11).

Heart catheterization (HC) yields prognostic measurements describing ventricular and pulmonary hemodynamics, including PVR. However, HC is an invasive procedure, in pediatrics often requires general anaesthesia and is associated with not negligible risks in this vulnerable population(12). Non-invasive echocardiography provides cardiac function parameters and estimation of several pulmonary hemodynamic characteristics. Yet, operator dependency and patient body habitus restrictions hamper objective quantification, accuracy and reproducibility and limit its use both in clinical decision making and as end point in clinical trials. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) provides non-invasive, reference standard volume- and flow measurements with high spatial resolution and is less prone to limitations encountered with echocardiography. Furthermore, CMR has shown promising results in pediatric PAH in distinguishing disease from controls. However, its wide accessibility may be limited by the required infrastructure and expertise(13).

A conceptual limitation of the conventional evaluation in PAH is that they separately describe cardiac function by echo and pulmonary vascular characteristics by HC. Since RV performance is directly dependent on its pulsatile and resistive afterload, there is growing interest in the ventricular-vascular coupling ratio (VVCR), a variable that incorporates ventricular contractility and vascular afterload and that quantifies their interaction as a measure of the efficiency of cardiovascular performance.

A growing body of literature has investigated the role of VVCR in understanding the pathophysiology of PAH(14–16). VVCR, however, is difficult to measure safely in pediatric clinical practice as multiple pressure-volume loops must be generated with varying preloads(17). Therefore, estimations of VVCR have been described using the single-beat method (VVCRRHC) by RHC, and recently non-invasively by volumetric data obtained with CMR (VVCRCMR)(15,18). VVCRRHC and VVCRCMR have been demonstrated to be predictive of RV failure and survival in adults with pulmonary hypertension (14,15,19). However, to assess the clinical value of VVCR as a potential marker of disease severity in pediatric PH, a larger multi-cohort study was required in which both estimations of VVCR would be correlated with expanded measures of disease severity. Patients with PAH only, treated at different centers, would be needed in order to study a population with a spectrum of disease severities from a homogenous underlying pathophysiology.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the role of VVCR as a clinical tool to assess disease severity in PAH children from two major PAH referral centers. We hypothesize that VVCRCMR will correlate with VVCRRHC and that VVCRCMR and VVCRRHC correlate to conventional parameters of disease severity.

METHODS

Study population

Patient data were collected retrospectively from medical records at two major referral centers for pediatric PAH: Children’s Hospital Colorado (CHC), Denver, Colorado, USA and University Medical Center Groningen/Beatrix Children’s Hospital (UMCG), Groningen, the Netherlands. We identified consecutive patients referred to the centers from January 2009 to March 2016, with an established PAH diagnosis before age 18 years and determined by HC using standard criteria(20,21). We included patients who had undergone an RHC and a CMR study within 30 days of one another. Clinical disease severity was assessed by World Health Organization functional class (WHO-FC), PVRi, mPAP and mean right atrial pressure (mRAP)(4,10,22). Excluded were patients with anatomical RV obstruction, abnormal RV volume loading, or with conditions possibly interfering with normal myocardial responses, namely: 1) pulmonary valve or pulmonary arterial stenosis; 2) previous surgical or catheter-intervention on the pulmonary valve or pulmonary arteries; 3) previous right ventriculotomy; 4) congenital heart disease more complex than simple atrial septal defect; 5) more than mild pulmonary insufficiency; and 6) presence of arrhythmias and 7) unavailability of a RV pressure tracing. The study was carried out with the approval of each centers’ Institutional Review Board and in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

VVCR estimation

VVCR represents the ratio of contractility to afterload and reflects the ability of the ventricle to alter contractility in response to changes in afterload, in order the maintain cardiac output. VVCR has been represented in the literature as the ratio of Ees/Ea or Ea/Ees. End-systolic elastance (Ees) is an index of myocardial contractility and is a generally accepted measure independent of pre- or afterload(23). Arterial elastance (Ea) is a validated reference measure of afterload encountered by the right ventricle(24).

Right heart catheterization and VVCRRHC

By institutional convention, all HC procedures were performed under general anaesthesia. A balloon wedge catheter was inserted through the femoral vein or internal jugular vein and advanced through the right heart to the pulmonary arteries by standard methods. Hemodynamic measures obtained included mean, systolic and diastolic pulmonary artery pressures, systolic and end-diastolic RV pressures, mRAP and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP). Systemic and pulmonary flows were calculated by the Fick equation using assumed oxygen consumption(25). Cardiac index, PVRi, SVRi and mPAP/mSAP were calculated using standard formulas. RHC-derived RV pressure tracings were analysed by one investigator (MD) using Matlab (The Mathworks, Natick, MA) to calculate VVCRRHC by single-beat method modified by Truong et al. (Fig. 1a)(16,18,26). In this method, end- systolic pressure (Pes) is estimated as the pressure 30 ms before minimum dP/dt (P30ms)(27).

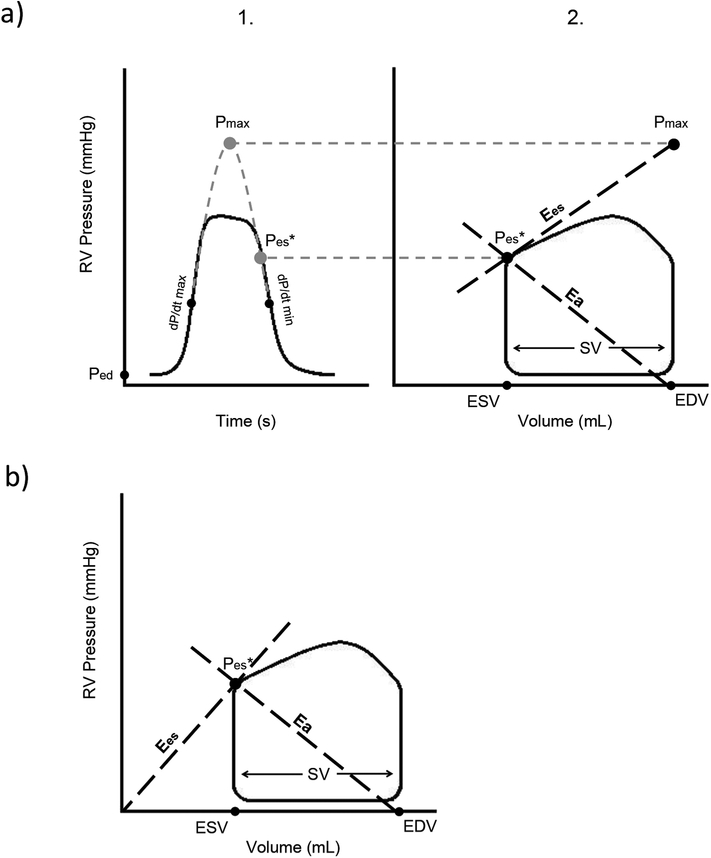

Figure 1:

Schematic overview of a) the single-beat method of determining VVCRRHC and b) the volume method of estimating VVCRCMR. a) At 1., theoretical maximum pressure of the right ventricle (Pmax) is estimated by fitting a sinusoid from early systolic (end-diastolic pressure (Ped) to maximum dP/dt) and early diastolic (minimum dP/dt to pressure equal to Ped) portion of the RV pressure tracing. This Pmax would occur in isovolumic contraction and is therefore located at end-diastolic volume in the pressure-volume loop. End-systolic pressure (Pes) is estimated as the pressure 30 ms before minimum dP/dt (P30ms). At 2., end-systolic elastance (Ees) is estimated by the ratio of Pmax minus Pes, to stroke volume (SV). Arterial elastance (Ea) is estimated as the ratio of Pes to SV. b) In the volume method, Ees is estimated as the ratio of Pes to end-systolic volume (ESV), in which volume at zero pressure (V0) is neglected. Ea is, similar to the single-beat method, estimated as the ratio of Pes to SV.

Cardiac magnetic resonance and VVCRCMR

All CMR studies were performed using a 1.5 Tesla Siemens Avanto or Aera (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlanger, Germany) or a 1.5 Tesla Philips Achieva (Philips Medical Systems, Best, Netherlands) scanner. Standard short-axis and horizontal long-axis SSFP cine images were obtained with breath holding during expiration using a retrospectively gated steady-state free precession sequence. Depending on the size of a subject, the parameters ranged from slice thickness of 4–10 mm, number of averages 1–3, TE 1.1–1.5, TR 2.8–3.5, and resolution 1.2–1.4 mm. The endocardial border was traced at end-systole and end-diastole using Qmass 7.6 software (Medis, Leiden, The Netherlands), and volumes were determined. Absolute volumetric measurements were indexed for body surface area (BSA) using the calculation of Haycock (28). Sanz’ approach was used to calculate VVCRCMR to represent Ea/Ees(Fig. 1b)(15). In our study, VVCRCMR is defined as SV/ESV(15) to represent Ees/Ea.

Statistical analysis

Categorical values are presented as absolute numbers and percentages and continuous variables as median and range. Normality was evaluated by Shapiro-Wilk tests. Relations between demographic data, age at diagnosis, age at CMR, age at RHC and PAH etiology with VVCRCMR and VVCRRHC were explored using Spearman correlation coefficients for continuous variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for categorical variables. To compare VVCRCMR to VVCRRHC, Spearman correlation coefficients were used. A Bland-Altman plot, which allows for comparison of two methods in the absence of the gold standard, was made to illustrate the difference between the two measurement methods. For the relationships between VVCRCMR, VVCRRHC and disease severity, Spearman correlation coefficients were used. All tests were two-tailed and a p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows (V23; IBM, Armonk, New York, NY).

RESULTS

Clinical data

A total of 27 consecutive patients with PAH were identified who had had both a RHC and CMR study ranging between 0 to 17 days in between. Patient characteristics, including hemodynamic and volumetric data, stratified by etiology, are presented in Table 1. PAH etiologies included idiopathic or heritable PAH (iPAH/hPAH) in 66.7%, PAH associated with congenital heart disease (PAH-CHD) 18.5% and PAH associated with other conditions (APAH) 14.8%. The latter conditions included connective tissue disease, drugs- or toxins, schistosomiasis and portal hypertension. Medication types included PDE5-inhibitors, endothelin antagonists, prostacyclin analogues and calcium channel blockers. There were no patients with monotherapy of prostacyclin analogues.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, volumetric and hemodynamic data of the patients, stratified by diagnosis

| Characteristics | All patients n=27 |

iPAH/hPAH n=18 |

PAH-CHD repaired, n=5 |

APAH-non-CHD n=4 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic/clinical | |||||

| Age at diagnosis, years | 9.3 (3.7–14.0) | 11.0 (3.9–14.3) | 4.6 (2.2–9.9) | 9.9 (2.3–13.8) | |

| Age at CMR study, years | 14.3 (11.1–16.8) | 14.4 (11.5–15.6) | 12.3 (6.3–19.4) | 14.7 (2.8–19.8) | |

| Time Dx enrolment, months | 46 (0–111) | 16 (0–124) | 92 (23–141) | 34 (6–96) | |

| Incident (Dx-enrolment < 3m) | 10 (37) | 8 (44) | 1 (20) | 1 (25) | |

| Time Dx enrolment, months | 0 (0–0) | ||||

| Prevalent (Dx-enrolment > 3m) | 17 (63) | 10 (56) | 4 (80) | 3 (75) | |

| Time Dx enrolment, months | 92 (47–139) | ||||

| Female | 16 (59) | 13 (72) | 2 (40) | 1 (25) | |

| Weight, kg | 50.0 (33.6–62.0) | 54.3 (32.5–62.5) | 46.0 (24.5–59.5) | 51.5 (15.4–64.5) | |

| BSA, m2 | 1.5 (1.2–1.7) | 1.6 (1.1–1.7) | 1.4 (0.9–1.6) | 1.5 (0.6–1.7) | |

| WHO-FC† | |||||

| I–II | 13 (59) | 8 (44) | 4 (80) | 1 (25) | |

| III–IV | 9 (41) | 6 (33) | 1 (20) | 2 (50) | |

| Treatment during CMR/RHC | |||||

| None | 3 (11) | 1 (6) | 1 (20) | 1 (25) | |

| Monotherapy by oral route | 8 (30) | 8 (44) | 0 | 0 | |

| Double therapy by oral route | 9 (33) | 5 (28) | 2 (40) | 2 (50) | |

| Combination therapy using prostacyclin analogue | 7 (26) | 4 (22) | 2 (40) | 1 (25) | |

| Days between CMR and catheterization | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–3) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–7) | |

| Hemodynamic data (RHC) | |||||

| Mean RAP, mmHg | 6 (4–8) | 6 (4–8) | 6 (6–12) | 6 (4–10) | |

| Mean PAP, mmHg | 40 (28–55) | 41 (27–57) | 35 (26–54) | 51 (28–54) | |

| Systolic PAP, mmHg‡ | 58 (44–78) | 67 (42–81) | 55 (40–74) | 65 (39–78) | |

| Diastolic PAP, mmHg‡ | 28 (17–37) | 30 (19–37) | 22 (13–41) | 26 (16–38) | |

| Systolic RVP, mmHg | 63 (42–79) | 63 (41–80) | 57 (41–79) | 73 (48–87) | |

| End-Diastolic RVP, mmHg* | 7 (6–10) | 7 (6–10) | 8 (8–12) | 6 (3–6) | |

| PCWP, mmHg | 9 (7–10) | 9 (7–10) | 9 (9–9) | 10 (8–13) | |

| Mean SAP, mmHg | 62 (52–69) | 65 (52–73) | 59 (52–62) | 64 (58–73) | |

| Mean PAP/Mean SAP, ratio | 0.7 (0.5–0.8) | 0.7 (0.4–0.9) | 0.6 (0.6–1.1) | 0.8 (0.4–0.9) | |

| PVRi, Wood units × m2 | 7.6 (4.1–12.2) | 7.6 (4.0–15.8) | 5.8 (3.2–16.4) | 10.3 (4.4–11.1) | |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 83 (70–91) | 81 (67–88) | 85 (67–152) | 93 (75–98) | |

| RVCI, l/min/m2 | 4.1 (3.3–4.5) | 4.0 (3.3–4.6) | 4.4 (2.7–5.6) | 4.1 (3.6–4.2) | |

| VVCRRHC | 1.1 (0.9–1.2) | 1.1 (0.9–1.2) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | |

| VVCR as Ea/Emax (RHC) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.8 (0.7–1.2) | |

| Volumes (CMR) | |||||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 84 (67–99) | 85 (69–99) | 77 (63–93) | 98 (61–146) | |

| RVEDVi, ml/m2 | 114 (100–148) | 107.4 (95.8–139.8) | 134.9 (108.1–173.6) | 133.6 (89.5–174.6) | |

| RVESVi, ml/m2 | 58 (45–79) | 56.7 (43.1–80.5) | 65.4 (46.2–111.7) | 68.2 (48.6–108.7) | |

| RVSVi, ml/m2 | 52 (45–62) | 51.3 (45.2–55.4) | 62.2 (52.8–74.5) | 63.3 (40.9–67.9) | |

| RV EF, % | 49 (35–53) | 48.8 (34.1–53.1) | 51.5 (36.9–57.4) | 44.6 (37.2–50.6) | |

| RVCI, l/min/m2 | 4.1 (3.6–5.5) | 4.0 (3.5–5.0) | 3.9 (3.7–6.8) | 5.8 (3.6–6.8) | |

| LVEDVi, ml/m2 | 85 (67–93) | 78.9 (66.2–93.1) | 96.1 (66.4–113.7) | 85.4 (80.9–85.9) | |

| LVESVi, ml/m2 | 35 (29–41) | 34.4 (25.9–41.1) | 40.9 (28.5–47.8) | 41.0 (35.2–55.2) | |

| LVSVi, ml/m2 | 48 (38–56) | 47.6 (39.8–54.5) | 61.6 (33.1–67.4) | 41.5 (28.6–50.7) | |

| LV EF, % | 58 (55–61) | 58.7 (55.4–62.7) | 57.9 (50.4–62.5) | 50.0 (34.3–59.0) | |

| LV CI, l/min/m2 | 3.8 (2.7–4.6) | 3.8 (2.8–4.7) | 3.9 (3.0–4.7) | 3.7 (2.6–5.3) | |

| Qp/Qs | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 1.0 (1.0–2.2) | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) | |

| VVCRCMR | 1.0 (0.5–1.1) | 1.0 (0.5–1.1) | 1.1 (0.7–1.4) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | |

| VVCR as Ea/Emax (CMR) | 1.0 (0.9–1.8) | 1.1 (0.9–1.9) | 0.9 (0.7–2.1) | 1.2 (1.0–1.7) | |

n = 22

n = 24

n = 26

Continuous data is shown as median (interquartile range) and categorical data as no. (%). BSA, body surface area; iPAH, idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension; hPAH, hereditary pulmonary arterial hypertension; PAH-CHD, pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease; APAH-non-CHD, associated pulmonary arterial hypertension non-congenital heart disease; RAP, right atrial pressure; PAP, pulmonary arterial pressure; RVP, right ventricular pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; SAP, systemic arterial pressure; PVRi, pulmonary vascular resistance index; SVRi, systemic vascular resistance index; RV CI, right ventricular cardiac index; VVCRRHC, catheterization-derived ventricular vascular coupling ratio; RVEDVi, right ventricular end-diastolic volume index; RVESVi, right ventricular end-systolic volume index; RVSVi, right ventricular stroke volume index; RV EF, right ventricular ejection fraction; LVEDVi, left ventricular end-diastolic volume index; LVESVi, left ventricular end-systolic volume index; LVSVi, left ventricular stroke volume index; LV EF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LV CI, left ventricular cardiac index; Qp/Qs, ratio of pulmonary flow to systemic flow; VVCRCMR, CMR-determined ventricular-vascular coupling ratio.

VVCRCMR versus VVCRRHC

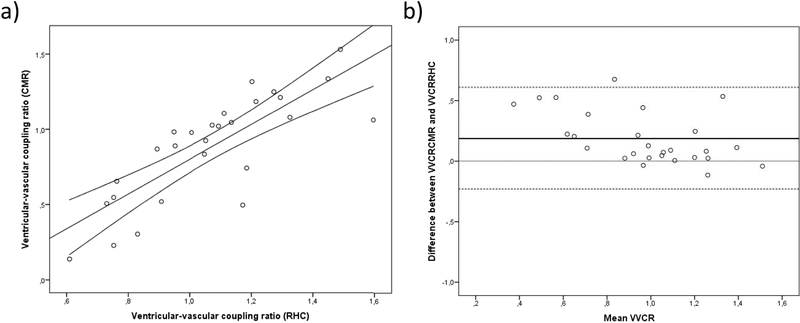

As shown in Fig. 2a, VVCRCMR (median 1.0; IQR 0.5–1.0) and VVCRRHC (median 1.1; IQR 0.9–1.2) were strongly correlated (r=0.83, p<0.001). A mean difference was demonstrated between VVCRCMR and VVCRRHC of 0.19 (95%-CI: −0.23–0.61) (Fig. 2b). Neither VVCRCMR nor VVCRRHC was found associated with gender or etiology of PAH, or correlated with age at diagnosis, age at CMR, age at catheterization or BSA (data not shown). Of note, there were no significant differences in heart rate (p=0.77) or RV CI (p=0.24) during RHC and CMR. Furthermore, both measures of VVCR correlated similarly with RVEDVi (VVCRCMR 0.65, p<0.01; VVCRRHC 0.63, p<0.01).

Figure 2:

a) correlation and 95% confidence interval between catheterization-derived (VVCRRHC) and CMR-derived ventricular-vascular coupling ratio (VVCRCMR). b) Bland-Altman plot demonstrating the differences between VVCRRHC and VVCRCMR. Mean ventricular-vascular coupling ratio (VVCR) is calculated as (VVCRCMR + VVCRRHC)/2. Mean difference between VVCRCMR and VVCRRHC (middle black line) is 0.19 with a 95% interval of −0.23 to 0.61 (dashed lines).

VVCRCMR versus VVCRRHC; disease severity

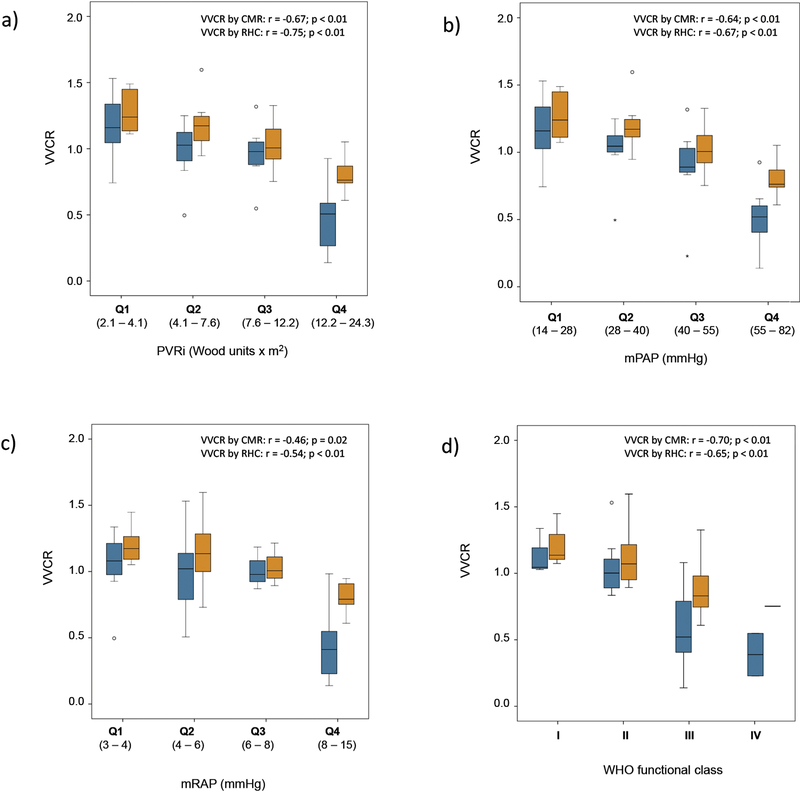

Both coupling measures correlated negatively with the clinical measures of disease severity PVRi, mPAP, mRAP and WHO-FC (all p ≤ 0.02). The relationship between VVCRCMR and VVCRRHC and the parameters of disease severity in quartiles is demonstrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3:

CMR- and RHC-derived ventricular-vascular coupling ratio (VVCRCMR, blue; VVCRRHC, orange) to a) Pulmonary vascular resistance, indexed (Wood units × m2), b) Mean pulmonary artery pressure (mmHg), c) Mean right atrial pressure (mmHg) and d) WHO functional class; all in quartiles. The boxes represent the middle 50% of the studied population, with the black line being the median, and the whiskers represent 25% each. The cutoff points for quartiles were 4.1, 7.6, 12.2 Wood Units×m2 for PVRi; 4, 6 and 8 mmHg for mRAP and 28, 40 and 55 mmHg for mPAP.

DISCUSSION

This early descriptive study demonstrates that, in pediatric PAH, non-invasively measured VVCRCMR correlates well with the more established, invasively measured VVCRRHC. Furthermore, both correlate comparably well with currently used conventional parameters of disease severity. We describe the values of VVCRCMR and VVCRRHC in the largest study of pediatric PAH patients, by combining cohorts of two major referral centers for pediatric PAH. We are the first to correlate both measures of VVCR with multiple conventional measures of disease severity.

Currently, in children with PAH, tools for assessing disease severity and for defining prognosis or treatment targets are critical. The tools used in adult PAH are often not feasible in young children. Compared to adults, RHC for monitoring hemodynamics has higher risks in children associated with general anaesthesia or sedation. The risk for adverse events including death increases as age decreases(29,30). Non-invasive parameters such as the 6-minute walk distance or cardiopulmonary exercise test are not feasible nor reliable in young children due to insufficient compliance. Therefore, it is imperative that new diagnostic parameters are established and validated as tools to guide treatment strategies in this population.

Recent insights tend to shift the focus from examination of the right ventricle and the pulmonary vasculature separately towards the investigation of its interaction within the integrated cardiovascular system (31). As PAH is a typical example of a cardiac load-increasing disease in which there is a complex interaction between the vasculature and the ventricle, quantification of the right ventricular-vascular coupling ratio may be of additional value in the evaluation and clinical monitoring of PAH.

The findings in this study regarding VVCR are congruent with the theoretical framework and earlier studies. VVCR (as Ees/Ea) is theoretically optimal at 1.5–2, but in progressive load-increasing diseases associated with failing ventricular function such as PAH, VVCR eventually decreases (32). As expected, the values of VVCR found in this study, a median VVCRCMR of 1.0 (IQR 0.5–1.1) and a median VVCRRHC of 1.1 (IQR 0.9–1.2), suggest overall abnormal coupling between the RV and pulmonary vasculature in our study population. In comparison to earlier studies in adult PH, the values in our pediatric population suggest a more energy-efficient coupling. In a study of Vanderpool et al. in which 50 PH adults were evaluated by CMR and HC, mean VVCRCMR (as SV/ESV) was 0.8 and mean VVCRRHC values were 2.3 and 1.4 (depending on variations in method)(14). These authors found that after controlling for right atrial pressure, mPAP and SV, VVCRCMR was the only independent predictor of transplant-free survival. Furthermore, VVCRCMR was a stronger predictor than RV EF. In a study with 124 adult PH patients, VVCR was acquired as Ea/Emax(15). A mean VVCRCMR of 1.8 was found and a mean VVCRRHC of 1.3. In our patient population, VVCR as Ea/Emax would be respectively 1.0 by CMR and 0.9 by RHC. As there are no methodological differences in estimating VVCRCMR in these studies, the worse VVCRCMR values in both adult PH studies might be explained by impaired RV function in the subjects of those studies, indicated by an RV EF of 39% and 37% versus 49% in the pediatric population in the current study(14–15). When comparing VVCRRHC values between studies, methodological differences must be considered as explanation, as discussed below.

However, it is the relationship of VVCR with progressing disease severity that can eventually be of clinical significance. VVCR is thought to decrease little in early stages of load-increasing disease such as PAH, as SV is maintained by augmented RV contractility. In late stages of disease, the RV fails to adapt and a further decrease in VVCR is expected. In the current study, both VVCRCMR and VVCRRHC correlated well with conventional functional and hemodynamic parameters of disease severity. These findings are also congruent with those reported in adults with PAH(14,15). Impaired right ventricular-vascular coupling in PAH is likely to be a gradual and progressive feature and serial imaging could guide the clinician in this process. The typical decremental pattern of VVCR was distinct in this study, although more evident in VVCRCMR than in VVCRRHC. Hence, VVCRCMR may be more consistent with the theoretical concepts of decoupling in worse disease states and therefore more accurate in assessing disease severity. Further, during the timeframe of this study, one patient in this cohort died and one underwent a lung transplantation. VVCR values in the course of their disease were in the third and fourth quartile of the cohort. However, a gap in time of up to three years existed between the VVCR studies and the adverse events. A prospective study with long-term follow-up and well-defined outcome end points could describe the prognostic value of VVCR measured either by CMR or RHC more clearly.

As there is no gold standard to measure VVCR, in this study, two methods are compared which pertain most to the physiological systolic function (as Ees) and afterload (as Ea), and thus to the most physiologically sound VVCR. Both methods estimate VVCR as Ees/Ea but use partly different assumptions. Ees is a broad accepted measure of contractility, but in the single-beat method Pes is necessary. By using only standard protocol catheterization data, estimations for Pes are used as end- systole is not clearly distinguishable. For example, Vanderpool. et al, acquired different values of VVCRRHC by estimating Pes as mPAP or sRVP(14). However, mPAP was recently shown to be unfit as a surrogate for Pes when evaluating RV-arterial coupling in adult patients with PAH(33). When using pressure data only, the best estimation of Pes would be the pressure 30 milliseconds prior to minimum dP/dt(27). Nevertheless, as there is a constant timeframe in this method, different heart rates between subjects make this method sensitive to bias. In the volume method, Ees is simplified from Pes/(ESV-V0) to Pes/ESV. The neglect of V0 is physiologically incorrect as V0 is dependent on RV dilation in patients with PAH(19). The implication of this possible bias in this study is small, as RVEDVi correlated equally with both measures of VVCR. Furthermore, in both methods, Ea as Pes/SV is a limited representation of afterload. Pes/SV does compare well to the effective arterial elastance parameter, calculated with the three-element Windkessel model. Yet, in that model the resistive components of afterload are still simplified in comparison to the afterload measured by arterial input impedance spectrum. Moreover, because Pes/SV is used instead of (Pes – PCWP)/SV, PCWP is assumed to be negligible. It has been shown that incorporating PCWP in this formula makes Ea a physiologically more accurate surrogate for the actual effective arterial elastance(24).

An often-noticed point of discussion is the similarity of EF (SV/EDV) and VVCRCMR (SV/ESV). Indeed, VVCRCMR is clearly related to EF(15). Analysing both formulas closely, VVCRCMR can be described in terms of EF as VVCRCMR=1/([1/EF]-1). However, EF is more load-dependent than VVCRCMR, as EDV changes more than ESV per increase in venous return, as can be seen in the relationship between EDV and ESV (equal to the relationship of EF and VVCRCMR) which is positive but not linear. Therefore, in the regions of the curve with higher values of EDV and ESV, as in RV failure, ESV increases more than EDV. So, in that stage, each unit increase in EDV is accompanied by a larger than one unit increase in ESV. This also means that VVCRCMR changes more than EF in RV failure where RV dimensions increase. Therefore, VVCRCMR may be a more sensitive method of detection of RV failure. In addition, in this cohort, VVCRCMR was more normally distributed than EF, making it better suited for statistical analysis. These advantages of VVCRCMR, together with the fact that VVCRCMR is a reflection of both vascular and ventricular function, rather than EF with only reflects ventricular function, make VVCRCMR a more complete measure of disease progression than EF.

LIMITATIONS

This study has some limitations associated with its retrospective nature and the limited number of patients. CMR and RHC were not performed simultaneously. However, with a median time of 1 day (IQR: 1–2) between both investigations, both conditions were assumed to be representative for a similar disease state in the individual patient. Differences between VVCRCMR and VVCRRHC values could be further affected by methodological differences. During RHC, institutional standards calls for general anesthesia, while unsedated CMR is often attempted in children older than 7 years to avoid anesthesia. CMR also requires breath-holding to limit motion artifact, which is not necessary during RHC. The technical determination of VVCRRHC by Matlab was limited in that three different types of pressure tracings were analysed; 2 types were image-based and the third was digitized data. The image-based types required image processing, which may account for minor differences within Pes and Pmax calculations between image types. We would have liked to demonstrate the prognostic importance of VVCRCMR and VVCRRHC as the adult PH study showed (14); however, the rates of transplant and death are thankfully too low in the pediatric population to perform survival analysis even with combined data from two large pediatric pulmonary hypertension centers. Larger studies involving combined data from multiple centers will be necessary to accomplish this. Finally, we acknowledge that VVCRCMR is not a direct measurement of ventricular vascular coupling, rather an estimation. That does not, however, mean it cannot be used in clinical care. The non-invasive nature of CMR and its safety profile make it an important tool for monitoring disease severity, risk stratification, and therapeutic management in children.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings in the current study indicate that in pediatric PAH, VVCR estimated noninvasively using CMR correlates well with VVCR measured at RHC, and that VVCR estimated by either method correlates well with clinical parameters of disease severity in children with PAH and may be an early predictor of RV failure. Therefore, VVCR may potentially be used for assessment of disease severity, risk stratification, timing of interventions and treatment decisions. Although both VVCRCMR and VVCRRHC are estimates of true physiologic ventricular-vascular coupling, this does not have to imply an obstacle to clinical implementation as both estimates were shown to correlate well with both hemodynamic and clinical parameters of disease severity in this study and thus may be of clinical value in monitoring patients with PAH. Also, despite the theoretical simplification for estimating VVCRCMR, studies in adult PH have shown VVCRCMR to be of prognostic value and thus of potential clinical use (14,15).

Future studies in pediatric PAH patients are required to assess the prognostic value of VVCR and compare this to other currently used prognostic parameters. Also, the prognostic value of treatment-induced changes in VVCR should be studied in order to establish VVCR as a treatment goal in pediatric PAH.

Highlights.

Ventricular-vascular coupling ratio (VVCR) is known to predict survival in adult PH.

In this multicenter study of pediatric PAH, VVCR by CMR correlates with VVCR by RHC.

VVCR by CMR and by RHC correlate well with established markers of disease severity.

Noninvasive VVCR by CMR warrants further studies to assess its prognostic value.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the CCTSI Maternal and Child Pilot Grant, the Children’s Hospital Colorado Research Scholar Award, Actelion ENTELLIGENCE Award, Jayden Deluca Foundation, the Frederick and Margaret Weyerhaeuser Foundation, the Sebald Fund and the National Institutes of Health NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR002535.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.D’Alonzo GE, Barst RJ, Ayres SM, Bergofsky EH, Brundage BH, Detre KM, et al. Survival in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Results from a national prospective registry. Ann Intern Med.1991;115(5):343–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tonelli AR, Arelli V, Minai OA, Newman J, Bair N, Heresi GA, et al. Causes and circumstances of death in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(3):365–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raymond RJ, Hinderliter AL, Iv PWW, Ralph D, Caldwell EJ, Williams W, et al. Echocardiographic predictors of adverse outcomes in primary pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(7):1214–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ploegstra MJ, Roofthooft MT, Douwes JM, Bartelds B, Elzenga NJ, van de Weerd D, et al. Echocardiography in pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension: early study on assessing disease severity and predicting outcome. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(1). pii: e000878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brierre G, Blot-Souletie N, Degano B, Tetu L, Bongard V, Carrie D. New echocardiographic prognostic factors for mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010;11(6):516–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghio S, Pazzano AS, Klersy C, Scelsi L, Raineri C, Camporotondo R, et al. Clinical and Prognostic Relevance of Echocardiographic Evaluation of Right Ventricular Geometry in Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(4):628–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Wolferen SA, Marcus JT, Boonstra A, Marques KM, Bronzwaer JG, Spreeuwenberg MD, et al. Prognostic value of right ventricular mass, volume, and function in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Hear J. 2007;28(10):1250–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baggen VJ, Leiner T, Post MC, van Dijk AP, Roos-Hesselink JW, Boersma E, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance findings predicting mortality in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2016;26(11):3771–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blalock S, Chan F, Rosenthal D, Ogawa M, Maxey D, Feinstein J. Magnetic resonance imaging of the right ventricle in pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2013;3(2):350–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ploegstra MJ, Zijlstra WM, Douwes JM, Hillege HL, Berger RM. Prognostic factors in pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2015;184:198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douwes JM, Roofthooft MT, Bartelds B, Talsma MD, Hillege HL, Berger RM. Pulsatile haemodynamic parameters are predictors of survival in pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J Cardiol.2013;168(2):1370–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beghetti M, Berger RMF, Schulze-Neick I, Day RW, Pulido T, Feinstein J, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of pediatric pulmonary hypertension in current clinical practice. Eur Respir J. 2013;42(3):689–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moledina S, Pandya B, Bartsota M, Mortensen KH, McMillan M, Quyam S, et al. Prognostic Significance of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Children With Pulmonary Hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(3):407–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanderpool RR, Pinsky MR, hc D, Naeije R, Deible C, Kosaraju V, et al. Right Ventricular-Pulmonary Arterial Coupling Predicts Outcome in Patients Referred for Pulmonary Hypertension. Heart. 2015;101(1):37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanz J, Garcia-Alvarez A, Fernandez-Friera L, Nair A, Mirelis JG, Sawit ST, et al. Right ventriculo-arterial coupling in pulmonary hypertension: a magnetic resonance study. Heart. 2012;98(3):238–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Truong U, Patel S, Kheyfets V, Dunning J, Fonseca B, Barker AJ, et al. Non-invasive determination by cardiovascular magnetic resonance of right ventricular-vascular coupling in children and adolescents with pulmonary hypertension. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2015;17(1):81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suga H, Sagawa K, Shoukas AA. Load independence of the instantaneous pressure-volume ratio of the canine left ventricle and effects of epinephrine and heart rate on the ratio. Circ Res. 1973;32(3):314–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takeuchi M, Igarashi Y, Tomimoto S, Odake M, Hayashi T, Tsukamoto T, et al. Single-beat estimation of the slope of the end-systolic pressure-volume relation in the human left ventricle. Circulation. 1991;83(1):202–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trip P, Kind T, van de Veerdonk MC, Marcus JT, de Man FS, Westerhof N, et al. Accurate assessment of load-independent right ventricular systolic function in patients with pulmonary hypertension. J Hear Lung Transpl. 2013;32(1):50–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simonneau G, Robbins IM, Beghetti M, Channick RN, Delcroix M, Denton CP, et al. Updated Clinical Classification of Pulmonary Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(1):S43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ivy D Advances in pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2012;27(2):70–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ploegstra MJ, Douwes JM, Roofthooft MT, Zijlstra WM, Hillege HL, Berger RM. Identification of treatment goals in pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1616–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Westerhof N. Describing right ventricular function. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(6):1419–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morimont P, Lambermont B, Ghuysen A, Gerard P, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, et al. Effective arterial elastance as an index of pulmonary vascular load. Am J Physiol Hear Circ Physiol. 2008;294(6):H2736–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaFarge CG, Miettinen OS. The estimation of oxygen consumption. Cardiovasc Res. 1970;4(1):23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brimioulle S, Wauthy P, Ewalenko P, Rondelet B, Vermeulen F, Kerbaul F, et al. Single-beat estimation of right ventricular end-systolic pressure-volume relationship. Am J Physiol Hear Circ Physiol. 2003;284(5):H1625–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alyono D, Larson VE, Anderson RW. Defining end systole for end-systolic pressure-volume ratio. J Surg Res. 1985;39(4):344–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haycock GB, Schwartz GJ, Wisotsky DH. Geometric method for measuring body surface area: a height-weight formula validated in infants, children, and adults. J Pediatr. 1978;93(1):62–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Byrne ML, Glatz AC, Hanna BD, Shinohara RT, Gillespie MJ, Dori Y, et al. Predictors of Catastrophic Adverse Outcomes in Children With Pulmonary Hypertension Undergoing Cardiac Catheterization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(11):1261–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beghetti M, Schulze-Neick I, Berger RMF, Ivy DD, Bonnet D, Weintraub RG, et al. Haemodynamic characterisation and heart catheterisation complications in children with pulmonary hypertension: Insights from the Global TOPP Registry (tracking outcomes and practice in pediatric pulmonary hypertension). Int J Cardiol. 2016;203:325–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Champion HC, Michelakis ED, Hassoun PM. Comprehensive Invasive and Noninvasive Approach to the Right Ventricle-Pulmonary Circulation Unit: State of the Art and Clinical and Research Implications.Circulation. 2009;120(11):992–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sagawa K, Maughan L, Suga H, Sunagawa K. Cardiac Contraction and the Pressure-Volume Relationship. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tello K, Richter MJ, Axmann J, Buhmann M, Seeger W, Naeije R, et al. More on Single-Beat Estimation of Right Ventriculo-Arterial Coupling in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2018;rccm.201802–0283LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]