Abstract

Pancreatic cysts are identified at an increasing frequency. Although mucinous cystic neoplasms represent a pre-malignant condition, the majority of these lesions do not progress to cancer. Over the last 10 years several societies have established guidelines for the diagnosis, initial evaluation and surveillance of these lesions. Here we provide an overview of five commonly used guidelines: 2015 American Gastroenterological Association, 2017 International Association of Pancreatology, American College of Gastroenterology 2018, European Study Group and American College of Radiology. We describe the similarities and differences between the methods used to formulate these guidelines, the population they target and their approaches towards initial evaluation and surveillance of cystic lesions.

Keywords: Pancreatic cyst surveillance, Cyst malignancy, Guidelines

Core tip: There are multiple different guidelines with the aim of establishing set guidelines for surveillance of pancreatic cysts. Our review article summarizes four of the most commonly used guidelines for pancreatic cyst.

INTRODUCTION

With the increasing utilization and resolution of cross-sectional imaging, the identification of pancreatic cysts has increased dramatically[1]. Even by conservative estimates, 3%-14% of all patients undergoing routine imaging are now incidentally found to have pancreatic cysts[2-6]. Multiple types of pancreatic cysts have been recognized, all with varying natural histories and malignant potentials. However, after excluding malignancies with cystic degeneration, mucinous cysts represent the predominant pre-malignant lesions, and these include main duct and branch duct intraductal papillary mucosal neoplasms (IPMNs), and mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs)[7]. Due to their prevalence and uncertain malignant potential, pancreas cysts may be a source of significant angst for both the patient and his/her provider[8,9]. Hence, guidelines have been formed to assist in clinical decision making with regards to pancreas cyst management and surveillance[10-12]. These guidelines serve two broad purposes: (1) To provide algorithms regarding a diagnostic work up or intervention at diagnosis or discovery of a pancreatic cyst and (2) To provide guidance regarding the method and timing of surveillance for those cysts that are potential precursors but without sufficient presumed risk to warrant intervention at diagnosis. In this review we have focused on the most recent update of the European Study Group guidelines, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) guidelines, the American College of Radiology and the International Association of Pancreatology guidelines[15-18]. As each guideline differs in its method of formulation, target population (i.e., all pancreatic cysts, mucinous cysts or IPMNs) and significant differences exist between the variables considered and timeline of surveillance recommended, our goal was to identify these differences and provide a practical overview to common clinical scenarios. Our focus was on the initial work-up and surveillance of cystic lesions by the guidelines, but it is important to note that some of the guidelines do make specific treatment recommendations (i.e., surgical approaches and post-operative surveillance) as well[13,14].

THE GUIDELINES

Here we will first consider each of the current guidelines with particular attention to the subset of cysts or cystic neoplasms they target, the mechanisms that led to the guideline formulation and their specific recommendations for initial management of cysts and surveillance of lower risk lesions. We have included the most broadly used guidelines developed in the last 5 years. For those guidelines that represent a revision of a prior version we discuss the differences or evolution of variables considered compared to prior iterations.

European based guidelines[15]

Target population: All pancreatic cystic neoplasms.

Method of formulation: These guidelines were formed by a multidisciplinary expert panel representing multiple different European associations. These guidelines differentiate pancreas cyst risk and surveillance based on the type of cyst defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) classification criteria, although do not offer specific upfront criteria to distinguish between and diagnose the different types of cysts [IPMN, MCN, serous cystic neoplasm (SCN), and undefined cysts].

Approach to initial risk stratification: These guidelines distinguish between absolute indications for surgery, where further work up is not recommended, and relative indications where “patients without significant comorbidity and one or more relative indications for surgery” are advised to undergo an operation.

(1) Suspected IPMN: Patients presenting with jaundice, an enhancing mural nodule ≥ 5 mm, solid mass, positive cytology, or a dilated main pancreatic duct (MPD) diameter measuring ≥ 10 mm meet the absolute indication. Relative indications for surgery are summarized in Table 1. Two features in these guidelines are notably unique: The inclusion of new onset diabetes and a cyst size cut-off of 4 cm (greater than the size criterion of 3 cm used in other guidelines). Notably, these guidelines include CA19-9 levels both as a relative indication and as a means of surveillance.

Table 1.

Variables considered in the initial evaluation of pancreatic cystic neoplasms

| European | ACG | AGA | IAP | ACR | ||

| Symptoms | Jaundice | AI | HR | HR | HR | HR |

| Pancreatitis | RI | HR | WF | |||

| Imaging based cyst characteristics | Main pancreatic duct dilation | > 10 mm AI 5-10 mm RI | > 5 mm HR | HR | > 10 mm HR 5-10 mm WF | > 10 mm HR 7-10 mm WF |

| Associated mass | HR | HR | HR | HR | ||

| Mural nodule | > 5 mm AI < 5 mm RI | HR | HR | > 5 mm HR < 5 mm WF | WF | |

| Cyst size | ≥ 4 cm RI | ≥ 3 cm HR | > 3 cm WF | > 3 cm WF | ||

| Parenchymal atrophy | WF | |||||

| Lymphadenopathy | WF | |||||

| Serum based | CA19-9 | RI | HR | WF | ||

| New onset diabetes | RI |

AI: Absolute indication; RI: Relative indication; HR: High risk; WF: Worrisome features.

(2) Suspected MCN: Patients with an MCN ≥ 40 mm, symptomatic from MCN or having risk factors such as mural nodules (irrespective of size) are also recommended surgery. Although these guidelines are unique in distinguishing MCNs and IPMNs, for lesions between 3 and 4 cm no clear guidance is provided. For lesions < 3 cm the IPMN guidelines apply.

(3) Suspected SCN: Asymptomatic patients should be followed for one year. After 1 year, symptom-based follow-up is recommended. Surgery is recommended in patients with symptoms related to compression of adjacent organs such as the bile duct or stomach.

(4) Undefined cysts: Patients with cysts of unclear etiology with no associated risk factors for malignancy, measuring < 15 mm are recommended to receive follow-up after one year. Patients with cysts ≥ 15 mm diameter are recommended to receive follow-up after six months. Follow up is recommended with MRI.

Approach to surveillance: (1) IPMN: Patients with a suspected IPMN that do not meet indication for surgery (indications mentioned above) are recommended to receive 6-month follow-up in the first year, and then yearly follow-up if no indications for surgery arise. The guidelines recommend continued surveillance so long as the patient remains surgically fit. Follow up surveillance is recommended with MRI and/or EUS (Table 2); (2) MCN: Patients with an MCN < 40 mm, in the absence of risk factors or symptoms, should undergo surveillance (MRI and/or EUS) every 6 mo for the first year, and then annually if no changes are observed; (3) Suspected SCN: Asymptomatic patients should be followed for one year. After 1 year, symptom-based follow-up is recommended; and (4) Undefined cysts: Cysts of unclear etiology measuring < 15 mm with no risk factors for malignancy should be re-examined after one year (MRI and/or EUS). If the cyst is stable for 3 years, follow-up may be extended to every two years. Cysts ≥ 15 mm, however, should receive follow-up annually after the first year.

Table 2.

Approach to surveillance of pancreatic cysts without high risk or worrisome features at diagnosis

| Size | IAP (Fukuoka) 2012 | IAP (Fukuoka) 2017 | ACG 2018 | ACR 2018 | European 2018 | AGA 2015 |

| < 1 cm | CT/MRI in 2-3 yr | CT/MRI in 6 mo then every 2 yr | MRI q 2 yr (lengthen after4) | MRI/CT q1 year for cysts < 1.5 cm and q6 mo for cysts 1.5-2.5 cm × 4 and then lengthen interval. Stop after stability over 10 yr1 | Surveillance q 6 mo × 2 with MRI and/or EUS, CA19-9. If stable lifelong surveillance is recommended with annual MRI/EUS, CA19-9. | MRI in 1 yr, then every 2 for 5 yr Stop if stable |

| 1-2 cm | CT/MRI annually × 2 yr, then lengthen interval if stable | CT/MRI in 6 m × 1 yr A Annually × 2 yr, then lengthen interval if stable | MRI q 1 yrs FOR 3 yr Then q 2 yr FOR 4 yr | |||

| 2-3 cm | EUS in 3-6 mo, then lengthen interval, alternate MRI with EUS as appropriate | EUS in 3-6 mo, then lengthen interval, alternate MRI with EUS as appropriate | EUS/MRI q 6mo for 3 yr then yearly for 4 yr | For cysts >2.5 cm q6 mo MRI/CT and then stop if stable for over 10 yr. For patients > 80 yr of age, q2 year imaging1. | ||

| > 3 cm | Alternate MRI/EUS every 3-6 mo | Alternate MRI/EUS every 3-6 mo | EUS/MRI q 6mo for 3 yr then yearly for 4 yr |

These guidelines use < 1.5 cm, 1.5-2.5 and > 2.5 as cut off values. CT: Computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; EUS: Endoscopic ultrasonography; ACG: American College of Gastroenterology; AGA: American Gastroenterological Association.

ACG guidelines for pancreatic cyst surveillance[16]

Target population: Patients who are found to have a pancreatic cyst but do not have a strong family history of pancreatic cancer or genetic mutations that predispose to pancreatic cancer.

Method of formulation: The guidelines were formed by an expert panel of gastroenterologists.

Approach to initial risk stratification: These guidelines are unique with respect to diagnosis of serous cystadenomas or pseudocysts and recommending cessation of surveillance. Although not included in the algorithms, the guidelines also consider solid pseudopapillary tumors and recommend surgery for these patients. An additional distinction of these guidelines is the central role symptoms (jaundice, pancreatitis) play. The guidelines do not focus on distinguishing high-risk stigmata beyond recommending a multidisciplinary evaluation of patients presenting with pancreatitis, jaundice or a mass. Those who do not have these features are stratified further by EUS if they have MPD dilation > 5 mm, parenchymal atrophy or a cyst size ≥ 3 cm. Smaller cysts without these features are surveyed by imaging. Again, the guidelines carefully specify that if EUS diagnosis of serous cystadenoma is achieved no further surveillance is indicated. Although CA19-9 levels are not incorporated into the algorithm, they are noted as a “high-risk” characteristic and therefore in patients in whom an IPMN or MCN is suspected and no other explanation of elevation of CA19-9 is found, a multidisciplinary evaluation is recommended. Finally, new onset DM is not included in the guidelines but is noted as a potential marker of a higher risk lesion.

Approach to surveillance: Patient with cysts measuring < 1 cm should undergo a shorter interval MRI in 2 years, whereas those with cysts 1-2 cm in one year and for cysts 2-3 cm in 6-12 mo. If the cyst remains stable, then a repeat MRI in one year is advised, after which providers are recommended to follow the surveillance guidelines based on cyst size (Table 1). Patients with cysts 1-2 cm with stable size and appearance after 3 years are recommended to undergo MRI every 2 years for the subsequent 4 years, and if the cyst remains stable, surveillance intervals may be lengthened further. Patient with cysts 1-2 cm with increase in cyst size (> 3 mm) should undergo shorter interval MRI or EUS/FNA within 6 mo. If the cyst is stable, then a repeat MRI in one year is recommended, followed by surveillance according to guidelines based on cyst size. Patients with cysts 2-3 cm and stable in size after 3 years should undergo MRI annually for 4 years, and if the cyst remains stable, surveillance intervals can be lengthened. Patients with cysts 2-3 cm with increase in cyst size (> 3 mm) should be referred to a multidisciplinary group with consideration of EUS/FNA.

AGA guidelines[17]

Target population: Patients with an asymptomatic pancreatic cystic neoplastic lesion. These guidelines specifically do not consider solid papillary neoplasms, cystic degeneration of adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors, and main duct IPMN without branch duct involvement.

Method of formulation: The guidelines were formed by the AGA Clinical Practice Guideline Committee, an expert panel of gastroenterologists. The authors developed a series of questions that would be addressed by the guidelines. The authors identified outcomes important for answering each question. The group then systematically reviewed and summarized the evidence for each outcome. The quality of evidence was divided into four categories rating from high to very low. The GRADE methodology was used with each question framed in the PICO format. Seven PICO questions were formed addressing initial imaging evaluation of cysts, surveillance of cysts, surgery for pancreatic cysts, surveillance after surgery, and when to discontinue surveillance.

Approach to initial risk stratification: No single clinical or radiologic feature was sufficient for the guidelines to recommend either EUS/FNA or consideration of resection. Patients identified as having two or more of the highest risk features (dilated MPD, ≥ 3 cm cyst size, or solid cystic component) are recommended to undergo EUS/FNA. Although the guidelines do not directly make recommendations for surgery it is stated that either the presence of a dilated PD and a mass or a positive cytology should be sufficient to recommend surgery. These guidelines do not differentiate an intermediate risk category. Patients with a cyst < 3 cm without a solid component or a dilated MPD should undergo surveillance.

Approach to surveillance: Patients with significant changes in the characteristic of the cyst including the development of a solid component, increasing size of the MPD, and cyst size ≥ 3 cm, are recommended to undergo EUS/FNA, and upon identification of any concerning cytology, be referred to surgery. These guidelines recommend against continued surveillance of pancreatic cysts if no significant changes have occurred over 5 years, or if the patient is deemed to no longer be a surgical candidate.

International Association of Pancreatology Guidelines 2017[18]

Target population: Patients with suspected IPMNs.

Method of formulation: These guidelines were formed by an expert multidisciplinary panel.

Approach to initial risk stratification: These guidelines categorize cysts into high risk, worrisome features, and low risk cyst groups. High-risk features include obstructive jaundice in a patient with a pancreatic head cyst, enhanced mural nodule ≥ 5 mm, or MPD ≥ 10 mm. These patients are advised to undergo surgery. Worrisome features include cyst ≥ 3 cm, enhancing mural nodules < 5 mm, thickened cyst walls, MPD 5-9 mm, abrupt change in the MPD with distal pancreatic atrophy, lymphadenopathy, elevated CA 19-9, or rapid cyst growth at a rate of > 5 mm over 2 years. These patients should be evaluated by EUS/harmonic EUS. If EUS reveals a definite mural nodule > 5 mm, main duct features suspicious for involvement, or cytology suspicious or positive for malignancy, these patients should be referred for surgery. In the absence of these features, cysts can be followed according to recommendations based on cyst size. However, the guidelines recommend strong consideration of resection for cysts > 3 cm in diameter in young fit patients who would otherwise require prolonged surveillance. All remaining cysts are stratified based on cyst size ranging from < 1 cm to 3 cm (Table 2).

Compared to the original guidelines released in 2012, the revised Fukuoka guidelines include the presence of a smaller (< 5 mm) enhancing mural nodule, lymphadenopathy, elevated CA 19-9, and increased growth rate of cyst in initial risk stratification.

Approach to surveillance: Surveillance guidelines are determined by cyst size (Table 2). The revised guidelines are more aggressive than those in 2012 and Sendai guidelines in 2006, with the recommendation for initial surveillance to occur at a shorter interval (within 6 mo for cysts < 2cm and within 3-6 mo for cysts 2-3 cm). This change emphasizes the potential significance of growth rate as a predictor of progression. Following initial risk stratification, cysts < 1 cm should be imaged every 2 years if there are no changes in the cyst. Cysts 1-2 cm should also be imaged every 2 years, whereas cysts 2-3 cm should undergo EUS or MRI yearly. As noted above, a size change alone (≥ 5 mm growth in 2 years), in addition to development of any worrisome features, is sufficient to recommend repeat EUS.

American College of Radiology 2017 White Paper[19]

Target population: Incidentally identified pancreatic cysts.

Method of formulation: These guidelines were formed by an expert multidisciplinary panel of Radiologists, Gastroenterologists and Surgeons.

Approach to initial risk stratification: The target “audience” for these guidelines is predominantly radiologists, and have certain unique features. For example, these guidelines rely on age as a determinant of the algorithm. A somewhat more conservative surveillance is recommended for patients > 80 years of age and for those between 65 and 80 with cysts < 1.5 cm. Similar to most other guidelines, high risk features include MPD > 10 mm, obstructive jaundice and enhancing solid component. Worrisome features include cysts > 3 cm, non-enhancing mural nodule, thickened enhancing cyst wall and a MPD > 7 mm. For cysts not meeting these criteria, size-directed short interval imaging is recommended.

Approach to surveillance: Patients with worrisome or high risk features during surveillance are recommended to undergo EUS. There are significant differences in the intensity of surveillance based on the age of the patient (for > 80 years of age re-imaging, every 2 years is recommended regardless of size) and baseline size (see Table 2). Notably, these guidelines recommend either contrast MRI or pancreas protocol CT as the preferred method of surveillance.

Comparison of guidelines and their performance

Differences in guideline development process: An expert, multidisciplinary panel consisting of gastroenterologists, surgeons, radiologists and pathologists formed the European guidelines, ACR and IAP/Fukuoka. The AGA guidelines were formed by a group of gastroenterologists after conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis. The ACG guidelines were also formed by a group of gastroenterologists after a literature review.

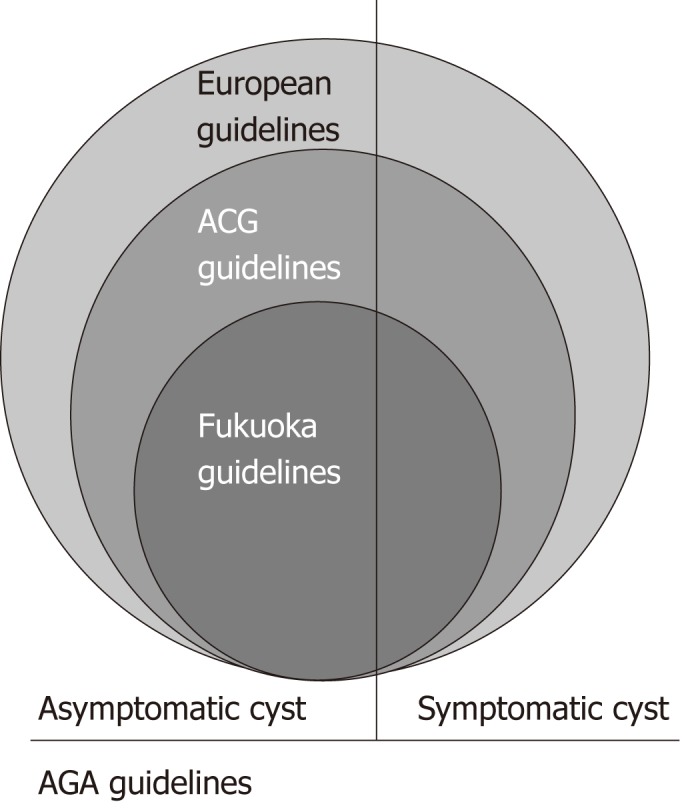

Differences in patient targets: The European guidelines are the most generalized, and applicable to all patients with pancreatic cystic neoplasms, asymptomatic or symptomatic. The AGA guidelines apply to patients with all types of cysts (although they must be asymptomatic) and exclude some very high-risk entities (such as MD IPMN). The ACR guidelines also pertain to all incidental cysts. The ACG guidelines apply to any type of pancreatic cyst (symptomatic and asymptomatic), and are the only guidelines that specifically exclude a possible genetic predisposition. Interestingly, none of the other guidelines alter their approach based on this association. The Fukuoka guidelines are the most specific, as they target only patients with IPMN (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Target populations. Although there is significant overlap between the guidelines this graph shows how the guidelines differ in the population they evaluate and make recommendations for. ACG: American College of Gastroenterology; AGA: American Gastroenterological Association.

Differences in variables: Clinical symptoms or presentation is only considered by the European, Fukuoka, and ACG guidelines. Specifically, the European and Fukuoka guidelines recommend symptomatic patients (e.g., jaundice, pancreatitis) be referred for surgery, while the ACG guidelines recommend symptomatic patients be referred for EUS/FNA and a multidisciplinary group discussion. Again, the AGA guidelines were not formed to address the management of symptomatic patients. No single clinical (or radiological feature) was sufficient for the AGA to recommend surgery or EUS/FNA, differentiating it from the other guidelines.

Cross-sectional or EUS imaging features are considered by all of the guidelines. All of the guidelines take into account cyst size and the size of the main pancreatic duct. Moreover, the European, ACG, and Fukuoka guidelines consider the presence of mural nodules. Increasing cyst size is also a variable considered by the European, Fukuoka, ACR and ACG guidelines. Lymphadenopathy and distal pancreatic atrophy is specifically considered in the Fukuoka guidelines only.

Biomarkers are considered (CA-19-9/cytology) by all of the guidelines. However, none of the guidelines considers molecular markers or fluid aspiration results.

The ACR white paper is the only set of guidelines that tailors its approach to the age of the patient (Table 1).

Differences in approach to initial surveillance: The AGA guidelines recommend that patients with 2 or more high risk features (enlarged MPD, solid cystic component, or > 3 cm cyst) should be referred for EUS/FNA. Positive cytology was considered in the European, Fukuoka, and ACG guidelines, and is an indication for referral to surgery in the European and Fukuoka guidelines, while the ACG guidelines recommended multidisciplinary referral and consideration of EUS/FNA. The presence of mural nodules is considered in the European, ACG, and Fukuoka guidelines. Specifically, patients with nodules > 5 mm are recommended for surgery in European and Fukuoka guidelines, while the ACG guidelines do not specify a size cut-off. The ACR guidelines define interval growth as > 20% change in greatest diameter. MPD size is another factor considered in all of the guidelines, although the European, ACG and Fukuoka guidelines have a size-cut off for what is high risk (> 5 mm in the ACG guidelines, > 10 mm in European and Fukuoka guidelines), while just the presence of an enlarged MPD is high risk in the AGA guidelines. It is important to note that the Fukuoka guidelines consider distal pancreatic atrophy, abrupt change in the MPD, and lymphadenopathy as “worrisome” criteria and therefore referral for EUS/FNA. The remaining initial surveillance criteria is determined by cyst size, with all of the guidelines outlining slightly different criteria (listed above) (Table 2).

Differences in long term surveillance: If there are no significant clinical or radiologic changes, lifelong surveillance (until the patient is no longer surgically fit) is recommended or suggested by most of the guidelines (European, ACG, and Fukuoka, with the exception of the AGA and ACR guidelines). The AGA recommends cessation of surveillance for cysts that do not show progression after 5 years, while the ACR recommends discontinuing surveillance after stability for 10 years (or sooner if the patients reaches 80 years of age after stability).

Differences in performance of guidelines: Performance of the surveillance guidelines is measured by their ability to identify patients with high-grade dysplasia or cancer. In a multicenter study comparing the performances of the AGA and Fukuoka guidelines across 4 patient cohorts, the sensitivity of the AGA guidelines ranged 7%-73% (7%, 28%, 56 % and 73%), and the specificity ranged 63%-93% (63%, 80%, 88% and 93%). The AGA guidelines demonstrated an accuracy ranging 75%-93%. The sensitivity of the Fukuoka guidelines ranged 28%-81% (28%, 58%, 73%, and 81%), and specificity ranged 34%-88% (34%, 45%, 79%, and 88%). The accuracy ranged from 49% to 84%[20]. These studies are difficulty to directly compare due to differences in methodology, criteria used for indication for resection (some have used only high-risk stigmata[21,22] and others both worrisome features and high-risk stigmata[20]), and differences in outcome (advanced neoplasia vs invasive cancer). However, they overall suggest that the Fukuoka guidelines likely will lead to a greater number of benign resections, but fewer missed cancers[20-22]. These results are summarized in Table 3. In an additional study comparing the final pathological outcome of surgically removed pancreatic cysts with the indications according to three guidelines (IAP, European Guidelines, and the AGA), surgery was found to be justfied (i.e., advanced neoplasia was found) in 54%, 53%, and 59% of patients who would have had surgery based on the IAP, European, and AGA guidelines, respectively. Furthermore, the AGA guidelines would have avoided resection the most, with the trade-off of 12% of patients with high grade dysplasia or maligancy being missed. Of note, neither the Fukuoka nor the European guidelines would have missed a case of advanced neoplasia in this cohort[23].

Table 3.

Comparison of performance between pancreatic cyst guidelines

| Studies | Comparisons | Outcome | Result | Performance |

| Sighinolfi et al[21], 2017 | Fukouka, AGA, and Sendai Criteria1 | Pancreatic Cyst with invasive cancer | AGA ROC 0.76, Fukouka ROC 0.78, Sendai ROC 0.65 (P < 0.001) | AGA and Fukuoka guidelines with higher diagnostic accuracy for neoplastic cysts compared to Sendai. |

| Xu et al[20], 2017 | AGA, Fukouka, and American College of Radiology1 | Advanced neoplasia (HGD or cancer) in resected pancreatic cysts | (Sen, Spec, PPV, NPV) AGA; 7.3%, 88.2%, 10%, and 84.1% Fukouka: 73.2%, 45.6%, 19.5%, 90.4% ACR: 53.7%, 61%, 19.8%, and 88% | AGA with higher specificity, but lower sensitivity than Fukuoka and ACR |

| Ma et al[22], 2016 | AGA and Fukouka2 | Advanced neoplasia (HGD or cancer) in resected pancreatic cysts | Fukouka: 28.2%, 95.8%, 74.1%, 75.9% AGA: 35.2.%, 94%, 71.4%, 77.5% | No significant difference between the two guidelines |

| Singhi et al, 2016 | AGA | Advanced neoplasia (HGD or cancer) | AGA: 62%, 79%, 57%, 82% | Low accuracy of AGA guidelines and continued surveillance of benign lesions (i.e., SCAs) |

| Lekkerkerker et al[23], 2017 | Fukuoka, AGA, European Guidelines | Advanced neoplasia (in patients with suspected IPMN) | Accuracy Fukuoka: 54% AGA: 59% European: 53% | AGA guidelines would have rec’d against surgery in most patients with benign lesions and would have missed significantly more HGD/CA |

These studies have considered high risk or worrisome features as sufficient for indication for resection (for example a cyst size > 3 cm would have qualified for an indication for surgery.

In these studies the presence of high risks stigmata or worrisome features with positive EUS/FNA were required. EUS: Endoscopic ultrasonography; ACG: American College of Gastroenterology; AGA: American Gastroenterological Association.

CONCLUSION

Management of pancreatic cystic lesions remains a significant challenge, and source of uncertainty and anxiety for providers and patients. The overall remarkable similarity between multiple guidelines is reassuring. However, as highlighted in our review, there are important and notable differences. Our goals was to identify and emphasize the differences that lead to the creation of these guidelines and assist the practicing clinician to navigate these guidelines to better care for patients with cystic neoplasms.

Unfortunately, there has not been a large, sufficiently powered study that compares these guidelines in a well-defined patient population. Therefore, it is difficult to recommend one guideline against another. However, we provide an overview of several studies that highlight the important differences between these guidelines.

We anticipate that over the next decade many more biomarkers and composite risk scores will be integrated into practice and it is our hope that these will become part of the standard of care and future guidelines. We anticipate that biomarkers and histologic diagnosis (for example, using mircorforceps biopsies) will enable greater precision in identifying pre-malignant cysts (i.e., IPMNs and MCNs) and allow the guidelines to primarily focus on these entities. Clearly, the greatest need will be for prognostic biomarkers that may help distinguish lesions at risk of progression from those that are not.

In summary, although surveillance of pancreatic cystic lesions offers a unique opportunity to recognize and prevent the development of pancreatic cancer, no current guideline has sufficient accuracy to definitively guide our diagnostic strategy. It is, however, likely that these guidelines are increasingly focusing our attention on relatively higher risk lesions and lessening the intensity of surveillance for low risk cysts.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: April 19, 2019

First decision: June 10, 2019

Article in press: July 19, 2019

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Barresi L, Crinò SF, Karstensen JG S-Editor: Ma RY L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Aws Hasan, Division of Digestive and Liver Diseases, Department of Medicine, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032, United States.

Kavel Visrodia, Division of Digestive and Liver Diseases, Department of Medicine, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032, United States.

James J Farrell, Division of Digestive Diseases, Department of Medicine, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520, United States.

Tamas A Gonda, Division of Digestive and Liver Diseases, Department of Medicine, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032, United States, tg2214@cumc.columbia.edu.

References

- 1.Lee HJ, Kim MJ, Choi JY, Hong HS, Kim KA. Relative accuracy of CT and MRI in the differentiation of benign from malignant pancreatic cystic lesions. Clin Radiol. 2011;66:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Jong K, Nio CY, Hermans JJ, Dijkgraaf MG, Gouma DJ, van Eijck CH, van Heel E, Klass G, Fockens P, Bruno MJ. High prevalence of pancreatic cysts detected by screening magnetic resonance imaging examinations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:806–811. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernández-del Castillo C, Targarona J, Thayer SP, Rattner DW, Brugge WR, Warshaw AL. Incidental pancreatic cysts: clinicopathologic characteristics and comparison with symptomatic patients. Arch Surg. 2003;138:427–423; discussion 433-434. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.4.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laffan TA, Horton KM, Klein AP, Berlanstein B, Siegelman SS, Kawamoto S, Johnson PT, Fishman EK, Hruban RH. Prevalence of unsuspected pancreatic cysts on MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:802–807. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brugge WR, Lauwers GY, Sahani D, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Warshaw AL. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1218–1226. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra031623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrell JJ. Prevalence, Diagnosis and Management of Pancreatic Cystic Neoplasms: Current Status and Future Directions. Gut Liver. 2015;9:571–589. doi: 10.5009/gnl15063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernández-del Castillo C, Adsay NV. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:708–713, 713.e1-713.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Correa-Gallego C, Ferrone CR, Thayer SP, Wargo JA, Warshaw AL, Fernández-Del Castillo C. Incidental pancreatic cysts: do we really know what we are watching? Pancreatology. 2010;10:144–150. doi: 10.1159/000243733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khannoussi W, Vullierme MP, Rebours V, Maire F, Hentic O, Aubert A, Sauvanet A, Dokmak S, Couvelard A, Hammel P, Ruszniewski P, Lévy P. The long term risk of malignancy in patients with branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farrell JJ. Pancreatic Cysts and Guidelines. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1827–1839. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4571-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandwani R, Allen PJ. Cystic Neoplasms of the Pancreas. Annu Rev Med. 2016;67:45–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-051914-022011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salvia R, Malleo G, Marchegiani G, Pennacchio S, Paiella S, Paini M, Pea A, Butturini G, Pederzoli P, Bassi C. Pancreatic resections for cystic neoplasms: from the surgeon's presumption to the pathologist's reality. Surgery. 2012;152:S135–S142. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spinelli KS, Fromwiller TE, Daniel RA, Kiely JM, Nakeeb A, Komorowski RA, Wilson SD, Pitt HA. Cystic pancreatic neoplasms: observe or operate. Ann Surg. 2004;239:651–657; discussion 657-659. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000124299.57430.ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meagher T, Armuss A. Pancreatic Cysts. J Insur Med. 2016;46:60–65. doi: 10.17849/0743-6661-46.2.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.European Study Group on Cystic Tumours of the Pancreas. European evidence-based guidelines on pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Gut. 2018;67:789–804. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elta GH, Enestvedt BK, Sauer BG, Lennon AM. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Pancreatic Cysts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:464–479. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2018.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vege SS, Ziring B, Jain R, Moayyedi P Clinical Guidelines Committee; American Gastroenterology Association. American gastroenterological association institute guideline on the diagnosis and management of asymptomatic neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:819–822; quize12-13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka M, Fernández-Del Castillo C, Kamisawa T, Jang JY, Levy P, Ohtsuka T, Salvia R, Shimizu Y, Tada M, Wolfgang CL. Revisions of international consensus Fukuoka guidelines for the management of IPMN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2017;17:738–753. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Megibow AJ, Baker ME, Morgan DE, Kamel IR, Sahani DV, Newman E, Brugge WR, Berland LL, Pandharipande PV. Management of Incidental Pancreatic Cysts: A White Paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:911–923. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu MM, Yin S, Siddiqui AA, Salem RR, Schrope B, Sethi A, Poneros JM, Gress FG, Genkinger JM, Do C, Brooks CA, Chabot JA, Kluger MD, Kowalski T, Loren DE, Aslanian H, Farrell JJ, Gonda TA. Comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of three current guidelines for the evaluation of asymptomatic pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e7900. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sighinolfi M, Quan SY, Lee Y, Ibaseta A, Pham K, Dua MM, Poultsides GA, Visser BC, Norton JA, Park WG. Fukuoka and AGA Criteria Have Superior Diagnostic Accuracy for Advanced Cystic Neoplasms than Sendai Criteria. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:626–632. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4460-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma GK, Goldberg DS, Thiruvengadam N, Chandrasekhara V, Kochman ML, Ginsberg GG, Vollmer CM, Ahmad NA. Comparing American Gastroenterological Association Pancreatic Cyst Management Guidelines with Fukuoka Consensus Guidelines as Predictors of Advanced Neoplasia in Patients with Suspected Pancreatic Cystic Neoplasms. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223:729–737.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lekkerkerker SJ, Besselink MG, Busch OR, Verheij J, Engelbrecht MR, Rauws EA, Fockens P, van Hooft JE. Comparing 3 guidelines on the management of surgically removed pancreatic cysts with regard to pathological outcome. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:1025–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]