Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to examine the severity of suicidal ideation of the older adults according to the amount of involvement in grandchild care. Data for this research were drawn from a cross-sectional study conducted on community-dwelling adults aged 65 years or older. The 922 participants were divided into three groups according to their involvement in grandchild care: 18.5% had provided daily care, 12.4% had provided occasional care, and 69.1% had never cared for their grandchildren. ANCOVA analysis showed that the scores for depression was significantly lower in the group which took care of their grandchildren occasionally compared to the other two groups. The scores for suicidal ideation was significantly higher in the group which had never taken care of their grandchildren compared to the other two groups. Current study suggests that grandparenting may have a positive effect on suicidal ideation of the older adults.

Keywords: Suicidal ideation, Older adults, Grandchild care, Grandparenting

INTRODUCTION

Due to increasing life expectancy and growing length of shared lifespan across multiple generations, grandparenting has become a very important matter in the aging population. While grandparents providing care for their grandchildren are increasing, reasons and patterns of grandparenting vary across cultural and ethnic backgrounds. In the United States, grandparents caring for grandchildren usually refer to custodial grandparents taking care of their grandchildren due to their dysfunctional adult children, associated with substance abuse, child abuse and neglect, intimate partner violence, parental incarceration, and etc [1]. In Europe, most grandparents provide care for their grandchildren complementary to parental care with no legal responsibilities for their grandchildren [2]. In China, grandparents caring for grandchildren have been influenced by the one-child policy and the dramatic increase in urban migration [3]. In South Korea, increasing number of mothers in full-time employment is the major cause of grandparents involved in grandchild care. It has been reported that Korean grandmothers were mostly providing care for their working daughter’s children [4].

While grandparents caring for their grandchildren could be beneficial for the parents, the children, and the society, these benefits may come at the cost of grandparent’s well-being. A large literature suggests the possible risks of grandchild care, especially custodial care, on elder’s mental and physical health. Grandparents providing extensive grandchild care may suffer from depression, isolation, disruption of social activities, declines in self-rated health, alternations in family relationships, increased level of stress, and financial difficulties [1,5,6]. On the contrary, recent studies revealing evidence of the possible positive impact of grandchild care on elder’s health are also increasing, especially those who do not provide extensive or primary grandchild care. Grandparenting have been related to less depression and loneliness, as well as better cognitive function [7,8].

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the prevalence of grandparents providing grandchild care in a South Korean population and examine the severity of depression and suicidal ideation of the older adults according to the amount of involvement in grandchild care.

METHODS

Subjects

Data for this research were drawn from the communitybased cross-sectional study conducted by Bucheon Mental Health Welfare Center and Soonchunhyang University Hospital Bucheon. The target population was community-dwelling adults aged 65 years or older living in Bucheon, a city in South Korea. People who visited the public facilities in Bucheon between October and December 2017 were enrolled in the study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Soonchunhyang University Hospital Bucheon (2017-10-009). For this research, participants without any grandchildren were excluded from the analysis.

Measurements

Through face-to-face interviews, information on the participants’ age, gender, marital status, education level, economic status, and living arrangement were collected. Suicidal ideation was asked with the question “Do you think about committing suicide?” 5-point Likert scale was used which 0 was “Never” and 4 was “Always.”

Participants were asked whether they had cared for their grandchildren. Participants were categorized into three groups according to the amount of involvement in grandchild care: “daily,” “occasionally,” and “never.” “Occasionally” was defined as more than once a month on a regular basis.

Short form of Geriatric Depression Scale (SGDS), a 15-item questionnaire, was used to measure the severity of depressive symptom of the participants [9]. The Korean version has been validated [10], and 8 was suggested as the optimal cut-off score for screening elderly depression [11].

Statistical analysis

Participants were categorized into three groups according to the amount of involvement in grandchild care. The sociodemographic variables between the three groups were compared by χ2-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA). To analyze the level of depression and suicidal ideation according to the groups, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with post-hoc analysis was used, with adjustment for age, gender, marital status, education level, economic status, and living arrangement. The depression score was also adjusted in the analysis for suicidal ideation of the groups. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20 and statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Among the 922 participants with grandchildren, 171 (18.5%) reported that they had cared for their grandchildren daily. 114 (12.4%) reported that they had cared for their grandchildren care occasionally, and 637 (69.1%) had never taken care of their grandchildren.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the three groups. Posthoc Bonferroni comparisons showed that the groups showed significant differences in age, gender, marital status, education level, economic status, and living arrangement. Participants were oldest in the group which had never taken care of their grandchildren and youngest in the group which provided occasional care. The group which didn’t provide grandchild care had higher percentage of participants with lower education level and poorer economic status than the other two groups. Percentage of participants who were separated/divorced or widowed, and those who were living alone were also higher compared to the other groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population according to the amount of involvement in grandchild care (N=922)

| Daily (N=171) | Occasional (N=114) | Never (N=637) | F or χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 74.5 (5.49) | 73.9 (6.50)a | 75.6 (6.02)b | 4.95† | 0.007 |

| Gender, N (%) | 8.66* | 0.013 | |||

| Male | 45 (26.2) | 46 (40.7) | 238 (37.4) | ||

| Female | 126 (73.8) | 68 (59.3) | 399 (62.6) | ||

| Education level, N (%) | 30.12‡ | 0.000 | |||

| <12 years | 102 (59.6) | 50 (43.9) | 420 (65.9) | ||

| ≥12 years | 69 (40.4) | 64 (56.1) | 217 (34.1) | ||

| Economic status, N (%) | 37.46‡ | 0.000 | |||

| Fair | 118 (69.0) | 82 (71.9) | 316 (49.6) | ||

| Poor | 53 (31.0) | 32 (28.1) | 321 (50.4) | 13.07* | 0.011 |

| Marital status, N (%) | |||||

| Married | 106 (62.0) | 79 (69.3) | 346 (54.3) | ||

| Separated/divorced | 5 (2.9) | 3 (2.6) | 42 (6.6) | ||

| Widowed | 60 (35.1) | 32 (28.1) | 249 (39.1) | ||

| Living arrangement, N (%) | 17.34‡ | 0.000 | |||

| Alone | 37 (21.6) | 29 (25.4) | 235 (36.9) | ||

| With other (s) | 134 (78.4) | 85 (74.6) | 402 (63.1) | ||

| SGDS score, M (SD) | 6.1 (1.98)b | 5.5 (1.74)a | 6.0 (1.95)b | 4.29* | 0.014 |

| Suicidal ideation, M (SD) | 1.3 (0.77)a | 1.5 (0.79)a | 1.7 (0.96)b | 11.25‡ | 0.000 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

a<b: post hoc analysis. SD: standard deviation, SGDS: short form of Geriatric Depression Scale

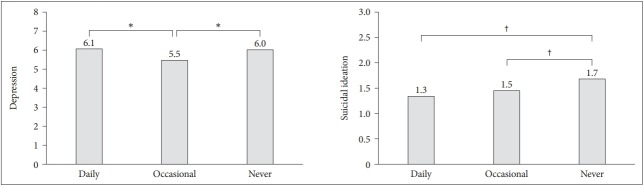

After adjusting for sociodemographic variables including age, gender, marital status, education level, economic status, and living arrangement, the ANCOVA analysis showed that the scores for depression was significantly lower in the group which took care of their grandchildren occasionally compared to the other two groups. After adjusting for sociodemographic variables and the depression score, the ANCOVA analysis showed that scores for suicidal ideation was significantly higher in the group which had never taken care of their grandchildren compared to the other two groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of adjusted means of depression and suicidal ideation of the participants according to the amount of involvement in grandchild care. *p<0.05, †p<0.001.

DISCUSSION

In this study, 30.9% of the participants cared for their grandchildren, in which 18.5% were providing daily care and 12.4% were providing occasional care. In a longitudinal study from 2006 to 2012 in Korea, among 1,948 grandmothers, 11.9% had cared for their grandchildren [12]. In a 2012 study, 13% of the grandparents participated in grandchild care and contributed an average of 52 hours per week to grandchild care [4]. The relatively higher prevalence rate of grandparents providing grandchild care in this study could be because the participants are all from an urban area. Also, it could reflect the fact that the number of caregiving grandparents are continuously increasing for the past few years. The maternal employment may be increasing, whereas public support for child care is still minimal in the Korean society. The result that participants were oldest in the group which had never taken care of their grandchildren also supports the fact that more grandparents are involved in grandchild care in recent years.

In demographic factors, the proportion of female was largest in those who took daily care of their grandchildren which would imply that grandmothers are more involved in grandchild care compared to grandfathers. Participants who had never taken care of their grandchildren had a more tendency to be undereducated, economically poor, divorced and to live alone. Providing care for their grandchildren is a very burdensome task and those who are more in a stable and fair circumstances could have had enough energy to spare for their grandchildren.

Participants who provided grandchild care occasionally had the lowest scores for depression compared to those who provided grandchild care daily and those who did not provide grandchild care. Our findings were consistent with the previous studies that grandparents providing occasional childcare are more likely to report better physical and psychological health, and higher quality of life compared to grandparents with primary care responsibility for a grandchild or those not involved in childcare at all. Grandparents providing grandchild care may benefit from the emotional rewards and gratification, reinforcing meaning in later life [13,14]. It could be assumed that providing care for their grandchildren may have a positive impact on the depressive symptoms of the older adults, only to the extent which does not become demanding and exceed one’s physical and psychological capacity.

Scores for suicidal ideation were higher in the participants who had not been involved in grandchild care than those who had been involved in grandchild care. According to the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide, thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness play a great role in one’s desire to die by suicide [15,16]. Thwarted belongingness includes lack of social connectedness and loneliness, which have been reported to be contributors to higher level of suicidal ideation in older adults [17]. By taking care of their grandchildren, older individuals can maintain a closer relationship with their adult children and grandchildren, feeling more connected and less lonely. Perceived burdensomeness is the belief that one is a burden to his or her loved ones and that one’s death would be worth more than one’s life to others [18]. Older individuals caring for their grandchildren may feel a sense of usefulness, competence, and self-worthy since they are contributing greatly to the family. Those providing daily care could be under a lot of stress, resulting in more depressive symptoms, but their significant role and presence in the family could prevent them from feeling worthless and developing suicidal ideation.

This study has several limitations. First, causal relationship cannot be inferred due to its cross-sectional design. Second, the characteristics and intensity of the participants’ involvement in grandchild care were not thoroughly evaluated. Third, physical health status, which is a very important factor affecting depression and suicidal ideation of the older adults, was not considered. Fourth, the results relied on self-reports.

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this is the first study that has investigated the association of grandchild care and suicidal ideation of the older adults. Future studies should adopt longitudinal analysis to increase our understanding of the impact of grandchild care on the suicidal ideation of the older adults, considering important factors such as physical health, reason for providing care, tasks and activities performed, presence of financial compensation and more.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Bucheon Mental Health Welfare Center and Soonchunhyang University Research Fund.

Footnotes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Jeewon Lee. Data curation: Doeun Lee. Formal analysis: Areum Lee. Funding acquisition: Han-young Jung. Investigation: Doeun Lee. Methodology: Shin-gyeom Kim. Project administration: Jeewon Lee. Resources: Soyoung Irene Lee. Software: Areum Lee. Supervision: Soyoung Irene Lee. Validation: Jeewon Lee. Visualization: Jeewon Lee. Writing—original draft: Jeewon Lee. Writing—review & editing: Soyoung Irene Lee.

REFERENCES

- 1.Choi M, Sprang G, Eslinger JG. Grandparents raising grandchildren: A synthetic review and theoretical model for interventions. Fam Community Health. 2016;39:120–128. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karsten Hank, Isabella Buber. Grandparents caring for their grandchildren: findings from the 2004 survey of health, ageing, and retirement in Europe. J Fam Issues. 2008;30:53–73. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ko PC, Hank K. Grandparents caring for grandchildren in China and Korea: findings from CHARLS and KLoSA. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;69:646–651. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee J, Bauer JW. Profiles of grandmothers providing child care to their grandchildren in South Korea. J Comp Fam Stud. 2010:455–475. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler FR, Zakari N. Grandparents parenting grandchildren: Assessing health status, parental stress, and social supports. J Gerontol Nurs. 2005;31:43–54. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20050301-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker LA, Silverstein M. Depressive symptoms among grandparents raising grandchildren: the impact of participation in multiple roles. J Intergener Relationsh. 2008;6:285–304. doi: 10.1080/15350770802157802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burn K, Szoeke C. Grandparenting predicts late-life cognition: results from the Women’s healthy ageing project. Maturitas. 2015;81:317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai FJ. The maintaining and improving effect of grandchild care provision on elders’ mental health–evidence from longitudinal study in Taiwan. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;64:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bae JN, Cho MJ. Development of the Korean version of the Geriatric Depression Scale and its short form among elderly psychiatric patients. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park JH, Kim KW, Kim M-H, Kim MD, Kim BJ, Kim SK, et al. A nationwide survey on the prevalence and risk factors of late life depression in South Korea. J Affect Disord. 2012;138:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung S, Park A. The longitudinal effects of grandchild care on depressive symptoms and physical health of grandmothers in South Korea: a latent growth approach. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22:1556–1563. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1376312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Gessa G, Glaser K, Tinker A. The health impact of intensive and nonintensive grandchild care in Europe: new evidence from SHARE. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2015;71:867–879. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen F, Liu G. The health implications of grandparents caring for grandchildren in China. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2016;71(5):867–879. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joiner T. Why People Die by Suicide. 2005. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Gordon KH, Bender TW, Joiner Jr TE. Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: Tests of the interpersonalpsychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:72–83. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanderhorst RK, McLaren S. Social relationships as predictors of depression and suicidal ideation in older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9:517–525. doi: 10.1080/13607860500193062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanley IH, Hom MA, Rogers ML, Hagan CR, Joiner Jr TE. Understanding suicide among older adults: a review of psychological and sociological theories of suicide. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20:113–122. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1012045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]