Abstract

Aims

Eight years ago, a paper‐based survey was administered during the World Pharma 2010 meeting, asking about the challenges of implementing pharmacogenetics (PGx) in clinical practice. The data collected at the time gave an idea about the progress of this implementation and what still needs to be done. Since then, although there have been major initiatives to push PGx forward, PGx clinical implementation may still be facing different challenges in different parts of the world. Our aim was therefore to distribute a follow‐up international survey in electronic format to elucidate an overview on the current stage of implementation, acceptance and challenges of PGx in academic institutions around the world.

Methods

This is an online anonymous LimeSurvey‐based study launched on 11 November 2018. Survey questions were adapted from the initially published manuscript in 2010. An extensive web search for worldwide scientists potentially involved in PGx research resulted in a total of 1973 names. Countries were grouped based on the Human Development Index.

Results

There were 204 respondents from 43 countries. Despite the wide availability of PGx tests, the consistently positive attitude towards their applications and advances in the field, progress of the clinical implementation of PGx still faces many challenges all around the globe.

Conclusions

Clinical implementation of PGx started over a decade ago but there is a gap in progress around the globe and discrepancies between the challenges reported by different countries, despite some challenges being universal. Further studies on ways to overcome these challenges are warranted.

Keywords: global, implementation, pharmacogenetics, survey

What is already known about this subject

Despite major efforts, pharmacogenetic (PGx) clinical implementation may still be facing different challenges in different parts of the world.

The majority of the documented efforts are concentrated in the USA and Europe.

Not much information is available from other parts of the world, with few exceptions.

What this study adds

There is currently a wide availability of PGx tests.

There is a consistently positive attitude towards PGx applications and advances in the field.

Progress of the clinical implementation of PGx still faces many challenges all around the globe.

1. INTRODUCTION

The field of pharmacogenetics (PGx) was born in the 1960s and ever since many genes and molecular signatures have been shown to play a role in altering drug response.1, 2 With the proven benefits of a personalized approach to medicine, it is crucial that all institutions worldwide start adopting such an approach in day‐to‐day healthcare delivery.3, 4 As naturally expected, discrepancies have been noted, with some institutions leading the way in this field and some falling behind. This observation pushed us to administer a survey during the World Pharma 2010 meeting, asking about the challenges of implementing PGx in clinical practice. The data collected at the time gave an idea about the progress of this implementation and what still needs to be done.5

Since then, there have been major initiatives to push PGx forward especially relating to developing clinical guidelines that are accessible and understandable by clinicians, and integration of PGx clinical decision support (CDS) into the electronic medical records (EMRs).3, 6 For instance, the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) of the Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase (PharmGKB) and the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group have already contributed to guidelines and clinical annotation levels of evidence covering 100 gene–drug interactions, translating known genetic laboratory test results into concrete clinical decision‐making regarding drug prescribing.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 In addition, in 2015, the EU funded a large PGx implementation study that takes into consideration the large diversity of healthcare systems and languages of citizens across Europe.12

Despite these efforts, PGx clinical implementation may still be facing different challenges in different parts of the world.3, 13, 14, 15, 16 In addition, the majority of the documented efforts are concentrated in the USA and Europe,12, 15, 17 while not much information is available from other parts of the world, with few exceptions.18, 19 Therefore, the aim of this study was to administer a modified version of the 2010 survey,5 in an electronic format and on an international scale. The added benefit is being able to compare and contrast differences in implementation and obstacles of PGx in clinical practice in different parts of the world and to compare the progress in the field 8 years after the initial study.

2. METHODS

This is an online anonymous LimeSurvey (version 3.14, Hamburg, Germany) based study that was approved by the American University of Beirut Institutional Review Board.

2.1. Target population

An extensive web search for worldwide scientists potentially involved in PGx research was performed using the following steps: all researchers who identified themselves on Google Scholar as research experts in pharmacogenomics, pharmacogenetics or personalized medicine were retrieved. The resulting list of names was further expanded by accessing known PGx websites, societies or research groups. The order followed is shown in Figure S1 whereby names extracted from the former search were not duplicated. The final list included a total of 1973 names for whom 1500 emails were publicly available and 328 additional ones were retrieved by using the services of RocketReach.co (Mountain View, CA, USA). Of note, the list mainly included scientists who were affiliated with academic centres and fewer scientists who were connected with diagnostic laboratories offering PGx testing. In addition, finding the email contacts of the latter was more challenging than finding those of academic scientists.

2.2. Instrument

Survey questions were adapted from the initially published manuscript in 2010.5 In addition to the original questions on demographics, availability of PGx tests and challenges for the implementation of PGx into clinical practice, several questions on knowledge of and attitudes towards PGx testing were added. Respondents were also asked whether they perform certain PGx tests in their laboratory for clinical use.

The LimeSurvey was developed and stored on the American University of Beirut server. All questions were optional and were available in the English language only. The Institutional Review Board approved the email invitation script and informed consent preceded the questions. To ensure anonymity, participants were not asked to sign or provide any personal identifiers.

The script included a statement clarifying that the survey is limited to genetic testing rather than phenotypic determination. It was also stated that the survey related to hereditary variants that have been shown to be involved in drug response; i.e. it is not related to accompanied diagnostics in oncology.

2.3. Data collection and analysis

The survey was launched on 11 November 2018, with 3 reminders sent at least 1 week apart. Data collection stopped on 24 December 2018, after which responses were exported from the LimeSurvey to an Excel sheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), then to SPSS (v. 24, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) after cleaning, merging and coding.

The countries for which the participants belonged to were coded into groups based on the Human Development Index (HDI) of the United Nations Development Programme report in 2018 (http://hdr.undp.org/en/2018‐update). Countries with very high HDI were categorized into 3 separate groups: 1 for North America (USA and Canada); 1 for European countries; and 1 for the rest of the countries (other).

Answers concerning the available PGx tests were merged when there was >1 respondent from the same country. A test was considered available when ≥1 respondent said so even if others from the same country were unsure or thought that the test is not available. If 2 respondents from the same institution gave contradictory answers, then test availability was categorized under uncertain. As for insurance coverage, the it depends category was coined when contradictory answers were provided especially when respondents came from different institutions within the same country. This category was also used when reimbursement varied depending on the test.

Lists of the top 3 challenges for PGx implementation were carefully reviewed by 2 authors (E.A.D. and N.K.Z.) and tallied into frequencies.

Data are presented as numbers with frequencies in tables and figures as appropriate. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

2.4. Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY,20 and are permanently achieved in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/2018.21

3. RESULTS

Out of 1581 who received emails, 243 participants accessed the survey, 39 of whose responses were excluded due to only opening the survey link or just entering some demographics data on the first page. The final sample size was therefore 204 (Figure S1).

3.1. Baseline characteristics of the respondents

Respondents came from 43 countries. The majority were faculty with a PhD and/or MD degree working in an academic setting. Most importantly, the survey respondents adequately represent members of the PGx community since all but 18 (8.8%) attended or provided ≥1 educational talk on PGx over the past year with 117 (57.4%) having done so more than twice (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the respondents [n (%)]

| ALL | Very high HDI—North Americaa | Very high HDI—Europeb | Very high HDI—Otherc | High HDId | Medium HDIe | Low HDIf | No country information | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 204 | n = 69 | n = 43 | n = 15 | n = 20 | n = 21 | n = 3 | n = 33 | |

| Job | ||||||||

| Academic | 163 (79.9) | 64 (92.8) | 41 (95.3) | 15 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (95.2) | 3 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Nonacademic | 8 (3.9) | 5 (7.2) | 2 (4.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 33 (16.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 33 (100) |

| Position | ||||||||

| Faculty | 139 (68.1) | 55 (79.7) | 32 (74.4) | 11 (73.3) | 18 (90) | 20 (95.2) | 3 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Student | 19 (9.3) | 9 (13) | 4 (9.3) | 4 (26.7) | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other g | 13 (6.4) | 5 (7.3) | 7 (16.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 33 (16.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 33 (100) |

| Highest professional title | ||||||||

| PhD | 106 (52) | 36 (52.2) | 24 (55.8) | 10 (66.7) | 14 (70) | 12 (57.1) | 1 (33.3) | 9 (27.2) |

| MD | 23 (11.3) | 10 (14.5) | 4 (9.3) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (5) | 4 (19) | 0 (0) | 3 (9.1) |

| MD/PhD | 23 (11.3) | 4 (5.8) | 11 (25.6) | 2 (13.3) | 3 (15) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.1) |

| PharmD | 20 (9.8) | 11 (15.9) | 2 (4.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 6 (18.2) |

| PharmD/PhD | 9 (4.4) | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (12.1) |

| Master's | 14 (6.9) | 4 (5.8) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 3 (14.3) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (9.1) |

| Other h | 3 (1.5) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| Missing | 6 (2.9) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (15.2) |

| Attendance or provision of educational talks on pharmacogenetics over the past year | ||||||||

| None | 18 (8.8) | 6 (8.7) | 3 (7) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (5) | 4 (19) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (6.1) |

| One | 26 (12.7) | 9 (13) | 3 (7) | 0 (0) | 7 (35) | 3 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 4 (12.2) |

| Two | 34 (16.7) | 8 (11.6) | 6 (14) | 3 (20) | 5 (25) | 7 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 5 (15.2) |

| More than two | 117 (57.4) | 44 (63.8) | 31 (72.1) | 11 (73.3) | 7 (35) | 6 (28.6) | 1 (33.3) | 17 (51.5) |

| Missing | 9 (4.4) | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (33.3) | 5 (15.2) |

HDI: Human Development Index (2018).

USA (62), Canada (7).

Belarus (1), Bulgaria (1), Croatia (1), Denmark (1), Estonia (1), France (1), Germany (4), Iceland (1), Italy (9), New Zealand (1), Portugal (1), Slovenia (3), Spain (4), Sweden (2), Switzerland (2), The Netherlands (8), UK (2).

Argentina (1), Australia (2), Brunei (1), Malaysia (8), Saudi Arabia (1), Singapore (1), United Arab Emirates (1).

Brazil (6), Iran (2), Jordan (5), Kosovo (1), Lebanon (2), Mexico (2), Republic of Moldova (1), Turkey (1).

Bangladesh (2), India (13), Indonesia (3), Pakistan (1), Palestine (1), South Africa (1).

Eritrea (1), Nigeria (1), Sudan (1).

Chief Technology Officer (1), Chief Technology Officer and Chief Security Officer (1), Clinical Development Pharmacist (1), Manager (1), Researcher (3), Senior Research Fellow (1), Staff (3), Teaching Assistant (1), Visiting Scientist (1).

BSc (Bachelor of Sciences) (1), MD Candidate (1), Registered Pharmacist (1).

3.2. Availability and reimbursement of clinical PGx tests

As shown in Table 2, all listed PGx tests and many more are currently offered in North America and Europe, and most are so in the other very high HDI countries. This is, however, coupled with some unevenness as illustrated in the following comment:

“We have varying levels of implementation in our region and across our country. Leading healthcare institutions have been early adopters, but it has taken a long time for others to jump on board.” (Survey ID: 195; very high HDI—North America)

Table 2.

Listing of available clinical pharmacogenetic tests

| COUNTRY | Responses (n) | Institutions (n) | Insurance coverage | Pharmacogenetic tests listed in the survey | Additional tests | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C19 | CYP2C9 | CYP2D6 |

CYP3A4

CYP3A5 |

DPYD | HLA‐A*31:01 B*15:02 | SLCO1B1 | TPMT | UGT1A1 | |||||

| Low HDI | |||||||||||||

| Eritrea | 1 | 1 | N/A | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Nigeria | 1 | 1 | N/A | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Sudan | 1 | 1 | ? | ? | ? | √ | √ | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | |

| Medium HDI | |||||||||||||

| Bangladesh | 2 | 2 | N/A | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| India | 13 | 13 | It depends | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Indonesia | 3 | 3 | N/A | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Pakistan | 1 | 1 | N/A | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| High HDI | |||||||||||||

| Brazil | 6 | 5 | It depends | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Iran | 2 | 2 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | √ | ? | |

| Jordan | 5 | 3 | ? | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | √ | x | |

| Lebanon | 2 | 2 | ? | √ | √ | √ | x | x | x | x | √ | x | |

| Mexico | 2 | 2 | ? | x | √ | √ | √ | ? | √ | ? | ? | ? | |

| Republic of Moldova | 1 | 1 | N/A | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Turkey | 1 | 1 | ? | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Very high HDI—other | |||||||||||||

| Argentina | 1 | 1 | x | √ | √ | √ | √ | x | x | x | x | x | CYP2A6, CYP2B6, NAT2, ABCB1, OCT |

| Australia | 2 | 2 | x | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Brunei | 1 | 1 | N/A | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Malaysia | 2 | 2 | x | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | x | √ | √ | |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | 1 | ? | x | x | x | x | x | ? | x | ? | ? | |

| Singapore | 1 | 1 | x | √ | ? | ? | ? | √ | √ | √ | ? | √ | HLA‐B*5701, HLA‐B*5801 |

| United Arab Emirates | 1 | 1 | ? | ? | x | x | ? | ? | ? | x | √ | ? | |

| Very high HDI—Europe | |||||||||||||

| Belarus | 1 | 1 | x | √ | √ | √ | √ | ? | √ | √ | ? | √ | ABC |

| Croatia | 1 | 1 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | x | √ | √ | √ | ABCB1, ABCG2, NAT2 |

| Denmark | 1 | 1 | x | √ | √ | √ | √ | x | x | ? | ? | ? | |

| Estonia | 1 | 1 | ? | √ | √ | √ | √ | ? | ? | ? | √ | ? | |

| France | 1 | 1 | ? | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Germany | 3 | 3 | x | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ABCB1, ABCG2 |

| Iceland | 1 | 1 | N/A | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Italy | 5 | 4 | x | √ | ? | √ | √ | √ | √ | ? | √ | √ | |

| Slovenia | 3 | 1 | x | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | SLC19A1, SLC6A4, MTHFD1, ABCC2 |

| Spain | 4 | 4 | It depends | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | CYP2B6, VKORC1, HLA‐B*5701 |

| Sweden | 1 | 1 | x | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | VKORC1, NAT2, IL28B |

| Switzerland | 2 | 2 | It depends | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| The Netherlands | 8 | 5 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | HLA‐B*5701 |

| UK | 1 | 1 | ? | ? | √ | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | VKORC1 |

| Very high HDI—North America | |||||||||||||

| Canada | 6 | 6 | It depends | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | VKORC1, IL28B, OPRM1, UGT2B15 |

| USA | 59 | 41 | It depends | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | CYP2B6, CYP4F2, VKORC1, HLA‐B*5701, HLA‐B*5801, G6PD, OPRD1, OPRM1, GRIK1, GRIK4, INFL3, ITPA, NUDT15, RYR1, mt‐RNR1, CACNAIS, CFTR, ADR2A |

HDI: Human Development Index (2018). Number of responses does not total 204 due to missing answers. X = no; √ = yes; ? = uncertain.

As for test reimbursement, the situation is different in each country and many times depending on the institution or test. Importantly, it appears that several European countries face this challenge although the cost of the tests is relatively cheaper than that of the USA. For example, testing for VKORC1 genetic polymorphisms with vitamin K dependent oral anticoagulants costs about 50 USD in Spain (Survey ID: 159) and 80 USD in Sweden (Survey ID: 32) compared to 400 USD in the USA (Survey ID: 196). In all 3 cases, third‐party payers do not cover the test cost. Of note that data from this table should be considered carefully in the context of the number of respondents and institutions per country.

3.3. Knowledge and availability of PGx tests in own laboratory

The majority of participants from all country groups knew what each PGx test is used for, especially for CYP enzymes (Table S1). As shown in Table S2, a number of laboratories perform some of the PGx tests for clinical testing, especially those from North America and in most of the laboratories of respondents from European countries with very high HDI. Interestingly, HLA genotyping is among the least available tests, an expected result, since the most compelling PGx evidence emanates from non‐Caucasian populations from South‐East Asia.22 In addition, none of the respondents from the 3 low HDI countries offer these tests in their laboratory for clinical use.

3.4. Attitudes towards implementation of PGx testing

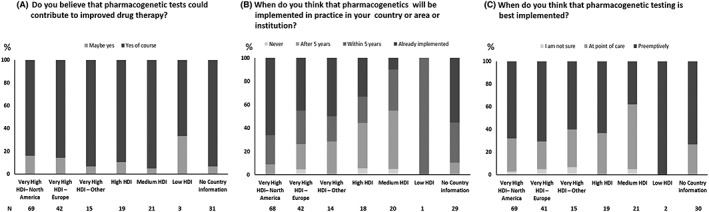

Almost all agreed that PGx tests could contribute to improved drug therapy (Figure 1A). As one would expect, clinical PGx testing is currently implemented in most very high HDI countries (Figure 1B). Nevertheless, one should be aware of the potential for a discrepancy between test availability and test implementation; as 1 participant commented:

“There is a difference between a test being orderable vs a test being implemented. In our health system, a couple genes are available through standard labs […] but I would not consider them to be implemented clinically.” (Survey ID: 184; very high HDI—North America)

Figure 1.

Attitudes (%) towards implementation of pharmacogenetic testing. HDI, Human Development Index

Finally, concerning the best timing for PGx implementation, there was no general consensus as to whether this should be done at point of care or pre‐emptively although a larger number of the respondents chose pre‐emptively (Figure 1C). One respondent commented:

“In a pre‐emptive testing model, it is more cost‐effective to order a pharmacogenetics panel than individual tests.” (Survey ID: 157; No country information)

Although another noted that reimbursement of the test may be a problem:

“Pre‐emptive testing: who will pay for it?” (Survey ID: 70; very high HDI—North America)

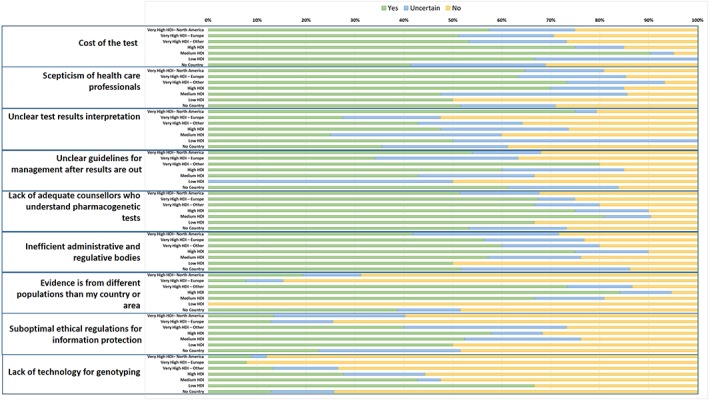

3.5. Challenges for bringing PGx into clinical practice

As shown in Figure 2, cost of the test, scepticism of health care professionals, unclear test results interpretation, unclear guidelines, and lack of adequate counsellors appeared to be relatively important challenges for all country groups, but with cost being perceived as most challenging in countries with high, medium and low HDI. Interestingly, administrative and regulative bodies were perceived to be inefficient mainly by countries with high HDI, and the challenges concerning evidence being from different populations, issues around information protection, and the lack of genotyping technologies ranked highest in countries with high, middle and low HDI, and those of very high HDI other than North America and Europe.

Figure 2.

Challenges (%) for bringing pharmacogenetics into clinical practiceThe country classification is based on the Human Development Index (HDI; 2018)Green: yes, blue: uncertain; orange: no

When asked to list the top 3 challenges for bringing PGx into clinical practice (Table 3) similar issues appeared among all country groups with cost and reimbursement being the most frequently cited challenge by respondents from countries with medium HDI. The need for educating physicians emerged as an important challenge in all country groups:

“Some clinicians may be unaware of the availability of PGx tests and their relevance.” (Survey ID: 214; very high HDI—Europe)

“Doctors need simple guidelines which translate genetic data into understandable medical reports.” (Survey ID: 22; very high HDI—Europe)

Table 3.

Top 3 challenges [n (%)] for bringing pharmacogenetics into clinical practice

| Very high HDI—North America | Very high HDI—Europe | Very high HDI—other | High HDI | Medium HDI | Low HDI | No country information | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of respondents | 62 | 32 | 12 | 19 | 16 | 2 | 27 |

| Challenges | 176 | 81 | 32 | 51 | 44 | 6 | 78 |

| Test cost and reimbursement | 39 (22.2) | 10 (12.3) | 6 (18.8) | 9 (17.6) | 13 (29.5) | 1 (16.7) | 13 (16.7) |

| Insufficient physician knowledge or awareness | 25 (14.2) | 13 (16.0) | 1 (3.1) | 3 (5.9) | 6 (13.6) | 1 (16.7) | 6 (7.7) |

| Physician scepticism or lack of interest | 15 (8.5) | 8 (9.9) | 6 (18.8) | 7 (13.7) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 9 (11.5) |

| Unclear test interpretation | 15 (8.5) | 6 (7.4) | 2 (6.3) | 2 (3.9) | 2 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 7 (9) |

| Limited evidence for clinical utility: clinical benefit and cost‐effectiveness | 14 (8) | 11 (13.6) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (2) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 4 (5.1) |

| Unclear or lack of guidelines | 9 (5.1) | 4 (4.9) | 1 (3.1) | 4 (7.8) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 12 (15.4) |

| Unavailability of test, technology, infrastructure, manpower or experts | 5 (2.8) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (6.3) | 4 (7.8) | 7 (15.9) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (5.1) |

| Lack of adequate counsellors or adequate communication of results | 3 (1.7) | 8 (9.9) | 1 (3.1) | 4 (7.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 6 (7.7) |

| Electronic medical records integration and clinical decision support | 17 (9.7) | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.8) |

| Data from different populations or ethnicities | 4 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 5 (15.6) | 6 (11.8) | 3 (6.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.8) |

| Insufficient public understanding or awareness | 3 (1.7) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (6.3) | 2 (3.9) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.6) |

| Lack of funding, investment or support | 0 (0) | 2 (2.5) | 3 (9.4) | 3 (5.9) | 3 (6.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Lack of legislative mandate or endorsement | 2 (1.1) | 4 (4.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.9) | 2 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Integration into clinical workflow | 7 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) |

| Turn‐around time and efficiency | 3 (1.7) | 3 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) |

| Suboptimal ethical regulations for information protection | 0 (0) | 4 (4.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (1.3) |

| Data management and bioinformatics | 3 (1.7) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.6) |

| Inefficient administrative and regulative bodies | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.9) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (2.6) |

| Lack of standardization of genotyping tests and results across laboratories | 5 (2.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Disconnect between clinical practitioners and researchers | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) |

| Patient expectations or concerns | 3 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Need for large‐scale genetic screening | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Unrealistic ideas to apply large‐scale genetic testing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) |

| Lack of alternative treatments | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Lack of parallel testing of drug levels | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Patient expectations or concerns | 3 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

HDI: Human Development Index (2018).

Number of respondents does not total 204 due to missing answers.

Number of challenges are less than the triple of the number of respondents due to unclassifiable answers such as knowledge, priority etc.

Nevertheless, an interesting challenge emerged concerning the potential disconnect between health care professionals and PGx experts and the need for collaboration; as 1 wrote:

“Missing link between clinical practitioners and active researchers in academia.” (Survey ID: 71; medium HDI)

Limited evidence for clinical utility mainly appeared in European countries with very high HDI, while challenges with EMR integration, CDS, data management and bioinformatics, integration with the clinical workflow, and lack of standardization of genotyping tests and results across laboratories were mostly limited to North America. In addition, data being from different populations or ethnicities and lack of funding, investment or support were mainly cited by respondents of countries with very high HDI other than North America and Europe. Inefficient administrative and regulative bodies were limited to high, medium and low HDI countries.

Public understanding, awareness and expectations were challenges of lesser importance. Interestingly, there were conflicting comments pertaining to whether there is a need for large‐scale genetic screening or whether this may actually complicate practice. Turn‐around time and lack of standardization of genotyping tests and results across laboratories may also contribute to this complexity, as 1 respondent commented:

“Many … labs start to offer PGx testing which is worrisome. The inconsistency of their genotyping platform and results is a foundation of the source of errors leading to variable interpretation.” (Survey ID: 162; very high HDI—North America)

4. DISCUSSION

This is a follow‐up international survey looking at the challenges of clinical implementation of PGx in different areas of the world. The initial evaluation conducted in 2010 was a paper survey confined to the attendees of World Pharma, whereas the current instrument is an international electronic survey directed to all PGx experts worldwide. As expected, the present data are richer, with 204 responses from 43 countries (as opposed to 53 responses from 28 countries in 2010).5 Interestingly, despite the wide availability of PGx tests and the consistently positive attitude towards their applications, the challenges impeding PGx clinical implementation did not change significantly, with cost and reimbursement, unawareness and scepticism of physicians, insufficient evidence, unclear guidelines and results' interpretation, and lack of adequate counsellors remaining relatively important challenges in all country groups. New challenges emerged especially in North America concerning data management and integration of CDS into EMR with lag in test turnaround time and interference with physician workflow. Lack of standardization of genotyping tests and results across laboratories also came out as a new challenge coupled with mixed feelings concerning large‐scale genetic screening and pre‐emptive genotyping. Unavailability of the test, infrastructure or manpower, lack of funding, and insufficient regulations including those revolving around information protection remained as important challenges impeding PGx implementation in countries with high, medium and low HDI.

4.1. Availability and reimbursement of clinical PGx tests

Many US and Canadian laboratories now offer PGx testing, which is becoming more broadly incorporated into clinical care.23, 24 In Europe, the number of laboratories offering PGx testing has significantly increased, and this has allowed broader access to PGx testing and more favourable turnaround time of test results.12 Other countries with lower HDI are still lagging behind as they need to overcome a number of barriers such as lack of funding, technology and infrastructure.

As for test reimbursement, it depends on the country and the institution, although there is a general agreement that cost is an important barrier, and that ideally it should be covered.14, 25 In order for a test to be covered by third‐party payers, test developers must demonstrate clinical utility.26 As such, the Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase has been aiming to clarify the level of action for pharmacogenomics biomarkers implied in each drug label as issued by the US Food and Drug Administration. It turned out that PGx levels in US labels were strongly associated with coverage of testing of pharmacogenomics biomarkers, with almost all labels with “Testing Required” having insurance coverage. Notably, in Japan, all labels listed as “Testing Required” were covered by the National Health Insurance.10

4.2. Knowledge and availability of clinical PGx tests in own laboratory

To our knowledge, this is the first survey to target participants who are PGx experts in the field as per inclusion criteria. Studies that are currently available in the literature have mainly addressed health care professionals including physicians and pharmacists and tackled different aspects of knowledge and practice with some overlap. For example in the USA, although the majority of the physicians who responded were aware of the value of PGx, those who have never ordered the test were not planning on doing so in the coming 6 months, mainly due to the lack of information they had about testing and about the genomic markers.14 More recently in Europe, Just et al.13 tested the knowledge of physicians and pharmacists concerning their own experience, knowledge about application, and interpretation of PGx testing. Most participants were familiar with classical genetics, pharmacology and drug metabolism, and the role of drug metabolizer phenotypes. However, less so in applying PGx tests, interpreting test results, and using them in therapeutic recommendations.13 Also, a study in Kuwait showed that “less than one‐fifth of [physicians and pharmacists] recognized that genetic determinants of drug responses do not change over a person's lifetime.”27

4.3. Attitudes towards implementation of PGx testing

All respondents hold a positive attitude when it comes to clinical implementation of PGx, which is in accordance with the findings in other studies such as from the USA,28 EU13 and Kuwait.27

When it comes to the best strategy for PGx testing, the lack of consensus could be due to the fact that the concept is relatively new and so far only limited to the USA and some European countries.29, 30 Emerging data have been supportive of the pre‐emptive PGx testing approach. By using EMRs and multi‐gene testing platforms, pre‐emptive genotyping is believed to provide an efficient mechanism to improve therapeutic decisions and outcomes based on PGx testing.29, 30, 31, 32 More efforts are ongoing to try and determine the most suitable strategy for PGx testing and to evaluate whether the pre‐emptive approach is cost‐effective in order to get buy‐in from third‐party payers.29

Concerning the timeframe of clinical implementation of PGx, results reflect the discrepancy between countries with very high HDI, which have already established infrastructure for clinical implementation of PGx for over a decade now,12, 15 and some countries with high, medium and low HDI, which are yet to reach that point. For example, in many European countries and the USA, and as noted above, academic centres are moving towards considerations and implementations of pre‐emptive genotyping.29, 30 Effort is being made in some other countries as summarized by a report in 2015.18 A 2016 study in Singapore has also shown that almost 30% of adverse drug reactions could have been prevented if PGx testing was pre‐emptively administered.33

4.4. Challenges for bringing PGx into clinical practice

Despite these success stories, there are still several challenges to overcome, some of which are universal, while others are more specific.

4.4.1. Challenges specific to countries with very high HDI

Challenges with EMR integration, CDS, data management and bioinformatics, and integration with the clinical workflow were mostly limited to countries with very high HDI especially North America, given its advanced healthcare system. EMRs can help facilitate the implementation and evaluation of PGx through point‐of‐care CDS,6 only as long as the electronic workflow is designed in a way that provides physicians with options to order specific tests depending on the case at hand, and also allows for result management. Currently, variations among health care record systems, coupled with problems such as lack of standardized genomic test results and interpretations, hinder interoperability and use of PGx testing in clinical practice. Several initiatives, such as CPIC and the Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Translating Genomic‐Based Research for Health, are working on creating standardized terminology that can be automatically uploaded into EMR's CDS, but it is likely that heterogeneity across systems will slow the process of implementation and development, at least initially.34

4.4.2. Challenges specific to countries with high, medium or low HDI

In addition to unavailability of or insufficient infrastructure, manpower, funding and regulations that are to be expected in countries with high, middle or low HDI, 2 additional challenges were notable. Those concerning ethical issues with information protection ranked highest. In an attempt to address these issues, review articles and recommendations from several groups have surfaced in the past years.35, 36, 37, 38, 39 The extent to which these guidelines are adopted by countries with high, medium or low HDI is mostly not known and hence necessitates further research.

Another problem in some countries is that the evidence for clinical utility applies to populations other than theirs, and hence it is unclear whether the choice of testing would be reproducible. For instance, less sequencing has been performed in non‐Caucasian populations.40 Also, data including all patterns of PGx variants in the Arab populations are scarce.27 More studies in different populations are therefore needed as they present opportunities for discovery that would be missed through the USA‐ or European‐only studies, and ensure that all populations and ethnicities benefit from PGx testing.41

4.4.3. Universal challenges

The need for educating physicians due to their insufficient knowledge or awareness emerged as an important challenge in all country groups. A nationwide survey conducted in the USA reported that despite knowing the impact of genetic profiles on drug response in patients, physicians admitted to lacking adequate knowledge to use PGx testing when prescribing drug therapy.14 More recently, in a 2018 survey of 285 physicians from 4 Implementing GeNomics In pracTicE (IGNITE) sites, only a third of the respondents agreed that their training prepared them to work with genetically high‐risk patients, and even fewer felt confident in their ability to use genetic results in practice.42 It is expected that physicians who receive some sort of formal training are more likely to be early users of PGx testing.14

Another challenge in this study was the lack of evidence for clinical utility. In fact, insufficient evidence for the clinical utility of testing was found to be a ubiquitous barrier to PGx implementation in practice.4, 14, 43 It is postulated that the more extensive the evidence is, the easier it would be to convince sceptical healthcare professionals and administrative and regulative bodies of the importance of implementing PGx testing. Nevertheless, this may not always hold true as there may still be a disconnect between what PGx experts perceive to be important for PGx testing and what physicians need, as beautifully stated by Stanek et al.: “PGx testing cannot be standard practice until physicians are comfortable with the science, believe in the clinical utility, understand when testing is clinically appropriate and know how to apply the results in practice.”14 As such, in the IGNITE survey, only 25% of physicians agreed that they could find and use reliable sources of information to understand and communicate genetic risk in the care of their patients.42 If PGx experts invest more in simplifying the evidence that is already available and presenting it in a manner that is friendlier to the medical community, they might contribute to lessening physician scepticism and enriching physician awareness. For instance, physicians can rely more on the evidence when it is translated into clinical practice guidelines, that inform them about the relevance of a given genotype in a specific clinical context.44 In other words, physicians would receive support from education, guidelines and computational tools, all integrated in 1 programme. An example is the translational pharmacogenomic programme led by St Jude Children's Research Hospital (St Jude, Memphis, TN, USA), where PG4KDS is a project aimed at evaluating PGx test results in children and selectively choosing the tests that have strong evidence and closely linking them to drug response, in order to incorporate them into patient medical records.45 Although other such initiatives are already in place, albeit only in countries with very high HDI,7, 8, 9, 10, 12 further collaborations and communications between PGx experts and healthcare professionals are needed.

“[Need] practice guidelines from physician organizations, i.e. generally trusted practice guidelines (not CPIC).” (Survey ID: 52; very high HDI—North America)

In addition to enhancing knowledge translation, bridging the gap between PGx experts and physicians may also indirectly address the challenge of result communication to patients, because a better‐informed physician would potentially be more comfortable in discussing results and choice of therapy with patients. Nevertheless, and since it is not always practical for physicians to integrate testing in their clinical workflow due to lack of time and poor EMR integration among other reasons (Table 3 ), the ideal would be to bridge both gaps in knowledge (of result interpretation) and practicality with a more adequate collaboration between physicians and counsellors who are also PGx experts. In fact, providing infrastructural support such as CDS and pharmacy consultation was found to be crucial as a first step, in order to set the stage for future healthcare education and training programmes in PGx.46 In cases where practitioners are not adequately trained, they would be assisted by a counsellor who understands and knows how to interpret PGx tests and results. In addition to physicians, multidisciplinary teams trained in PGx‐based drug selection and dosing can be of help in improving and disseminating PGx services offered to patients.12 For instance, the findings of a 2017 pilot study indicated that, in some clinical settings, pharmacists enhance the delivery of PGx testing by working with providers to interpret results appropriately.47

4.5. Limitations

The results of this study should be considered in light of some of the limitations that it holds. Even though the target population was larger than that of the previous study, the response rate was poor (13.5%), a rate that is to be expected with external online survey platforms.48 Nevertheless, the current data are more representative since country coverage is better than that of the initial survey.5 Additionally, since all survey questions were nonmandatory, 33 participants, unfortunately, chose not to reveal their country and institution. Furthermore, most of the targeted experts and respondents were scientists affiliated with academic institutions rather than connected to diagnostic PGx laboratories, and they were mainly PhDs, with a smaller proportion of MDs, hence giving valuable insight on the academic viewpoint of PGx knowledge and implementation, but not providing balanced clinical data in this regard. Finally, the survey questions did not address accompanied diagnostics in oncology; they also did not differentiate PGx test implementation from simple availability, a disparity that necessitates further exploration.

5. CONCLUSIONS

We have shown in this follow‐up study that, despite the wide availability of PGx tests, the consistently positive attitude towards their applications and advances in the field such as CDS integration into EMRs, progress of the clinical implementation of PGx still faces many challenges all around the globe. Efforts on standardization of PGx tests and their interpretation, and incorporation of CDS into EMRs should provide more common ground among heterogeneous health IT infrastructures and improve PGx integration in the clinical workflow.34 It is hoped that the rapid developments in next generation sequencing and machine learning lead to the further implementation of PGx in the clinic while still being practical and cost‐effective.49, 50, 51, 52

COMPETING INTERESTS

There are no competing interests to declare.

CONTRIBUTORS

E.A.D., R.Z., L.A.H. and N.K.Z. wrote the manuscript; I.C. and N.K.Z designed the research; E.A.D., R.Z., L.A.H. and N.K.Z. performed the research; E.A.D., R.Z., L.A.H. and N.K.Z. analysed the data.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Search strategy for the study participants

Table S1. Perceived knowledge [n (%)] concerning which drug(s) a particular pharmacogenetic test is for

Table S2. Availability [n (%)] of pharmacogenetics tests in own laboratory for clinical use

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank the participants who took the time to respond to the survey questions.

Abou Diwan E, Zeitoun RI, Abou Haidar L, Cascorbi I, Khoueiry‐Zgheib N. Implementation and obstacles of pharmacogenetics in clinical practice: An international survey. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85:2076–2088. 10.1111/bcp.13999

Elizabeth Abou Diwan, Ralph I. Zeitoun and Lea Abou Haidar contributed equally.

REFERENCES

- 1. Relling MV, Evans WE. Pharmacogenomics in the clinic. Nature. 2015;526(7573):343–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roden DM, Tyndale RF. Genomic medicine, precision medicine, personalized medicine: what's in a name? Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94(2):169–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cascorbi I. Significance of pharmacogenomics in precision medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;103(5):732–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bartlett G, Antoun J, Zgheib NK. Theranostics in primary care: pharmacogenomics tests and beyond. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2012;12(8):841–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ghaddar F, Cascorbi I, Zgheib NK. Clinical implementation of pharmacogenetics: a nonrepresentative explorative survey to participants of WorldPharma 2010. Pharmacogenomics. 2011;12(7):1051–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Osheroff JA, Teich JM, Middleton B, Steen EB, Wright A, Detmer DE. A roadmap for national action on clinical decision support. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14(2):141–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Relling MV, Klein TE. CPIC: clinical Pharmacogenetics implementation consortium of the pharmacogenomics research network. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89(3):464–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Swen JJ, Wilting I, de Goede AL, et al. Pharmacogenetics: from bench to byte. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83(5):781–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bank PCD, Caudle KE, Swen JJ, et al. Comparison of the guidelines of the clinical Pharmacogenetics implementation consortium and the Dutch Pharmacogenetics working group. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;103(4):599–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shimazawa R, Ikeda M. Pharmacogenomic biomarkers: interpretation of information included in United States and Japanese drug labels. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2018;43(4):500–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lennard L. Implementation of TPMT testing. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(4):704–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Swen JJ, Nijenhuis M, van Rhenen M, et al. Pharmacogenetic information in clinical guidelines: the European perspective. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;103(5):795–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Just KS, Steffens M, Swen JJ, Patrinos GP, Guchelaar HJ, Stingl JC. Medical education in pharmacogenomics‐results from a survey on pharmacogenetic knowledge in healthcare professionals within the European pharmacogenomics clinical implementation project ubiquitous pharmacogenomics (U‐PGx). Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73(10):1247–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stanek EJ, Sanders CL, Taber KA, et al. Adoption of pharmacogenomic testing by US physicians: results of a nationwide survey. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91(3):450–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Volpi S, Bult CJ, Chisholm RL, et al. Research directions in the clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics: an overview of US programs and projects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;103(5):778–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Waldman L, Shuman C, Cohn I, et al. Perplexed by PGx? Exploring the impact of pharmacogenomic results on medical management, disclosures and patient behavior. Pharmacogenomics. 2019;20(5):319–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lesko LJ, Schmidt S. Clinical implementation of genetic testing in medicine: a US regulatory science perspective. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(4):606–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mitropoulos K, Al JH, Forero DA, et al. Success stories in genomic medicine from resource‐limited countries. Hum Genomics. 2015;9(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Suarez‐Kurtz G, Aklillu E, Saito Y, Somogyi AA. Conference report: pharmacogenomics in special populations at WCP2018. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85(3):467–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harding SD, Sharman JL, Faccenda E, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY. Nucl Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D1091‐D1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alexander SP, Fabbro D, Kelly E, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174(Supp 1):S272–S359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Amstutz U, Shear NH, Rieder MJ, et al. Recommendations for HLA‐B*15:02 and HLA‐A*31:01 genetic testing to reduce the risk of carbamazepine‐induced hypersensitivity reactions. Epilepsia. 2014;55(4):496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moyer AM, Rohrer Vitek CR, Giri J, Caraballo PJ. Challenges in ordering and interpreting Pharmacogenomic tests in clinical practice. Am J Med. 2017;130(12):1342–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bousman CA, Zierhut H, Muller DJ. Navigating the labyrinth of pharmacogenetic testing: a guide to test selection. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019. 10.1002/cpt.1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ehmann F, Caneva L, Papaluca M. European medicines agency initiatives and perspectives on pharmacogenomics. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(4):612–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pezalla EJ. Payer view of personalized medicine. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(23):2007–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Albassam A, Alshammari S, Ouda G, Koshy S, Awad A. Knowledge, perceptions and confidence of physicians and pharmacists towards pharmacogenetics practice in Kuwait. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9):e0203033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lemke AA, Hutten Selkirk CG, Glaser NS, et al. Primary care physician experiences with integrated pharmacogenomic testing in a community health system. Per Med. 2017;14(5):389–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Roden DM, Van Driest SL, Mosley JD, et al. Benefit of preemptive Pharmacogenetic information on clinical outcome. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;103(5):787–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. van der Wouden CH, Cambon‐Thomsen A, Cecchin E, et al. Implementing pharmacogenomics in Europe: design and implementation strategy of the ubiquitous pharmacogenomics consortium. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;101(3):341–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dunnenberger HM, Crews KR, Hoffman JM, et al. Preemptive clinical pharmacogenetics implementation: current programs in five US medical centers. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;55(1):89–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. O'Donnell PH, Wadhwa N, Danahey K, et al. Pharmacogenomics‐based point‐of‐care clinical decision support significantly alters drug prescribing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;102(5):859–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chan SL, Ang X, Sani LL, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of adverse drug reactions at admission to hospital: a prospective observational study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(6):1636–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Overby CL, Kohane I, Kannry JL, et al. Opportunities for genomic clinical decision support interventions. Genet Med. 2013;15(10):817–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nuffield Council on Bioethics . Pharmacogenetics: ethical issues. 2004. www.nuffieldbioethics.org/fileLibrary/pdf/pharmacogenetics_report.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2019.

- 36. Wellcome Trust . Pharmacogenetics‐Ethical Issues Response of the Wellcome Trust. 2004. www.wellcome.ac.uk/stellent/groups/corporatesite/@policy_communications/documents/web_document/wtd002776.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2019.

- 37. European commission independent expert group . 25 recommendations on the ethical, legal and social aspects of genetic testing: research, development and clinical applications. 2004. http://europa.eu.int/comm/research/conferences/2004/genetic/pdf/recommendations_en.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2019.

- 38. European Commission . Polymorphic sequence variants in medicine: Technical, social, legal and ethical issues pharmacogenetics as an example (draft). 2004. www.eshg.org/ESHG‐IPTSPGX.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2019.

- 39. Department of Health and Human services. USA . Secretary's Advisory Committee on Genetics, Health, and Society. Realizing the Promise of Pharmacogenomics: Opportunities and Challenges (Report). 2007. https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/bitstream/handle/10822/510844/DHHS%20‐%20Promise%20of%20pharmacogenomics%20‐%20draft%20‐%20032307.pdf;sequence=1. Accessed January 30, 2019.

- 40. Cascorbi I, Tyndale R. Progress in pharmacogenomics: bridging the gap from research to practice. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;95(3):231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Perera MA, Cavallari LH, Johnson JA. Warfarin pharmacogenetics: an illustration of the importance of studies in minority populations. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;95(3):242–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Owusu OA, Fei K, Levy KD, et al. Physician‐reported benefits and barriers to clinical implementation of genomic medicine: a multi‐site IGNITE‐network survey. J Pers Med. 2018;8. pii: E24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Melzer D, Detmer D, Zimmern R. Pharmacogenetics and public policy: expert views in Europe and North America. Pharmacogenomics. 2003;4(6):689–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Amstutz U, Carleton BC. Pharmacogenetic testing: time for clinical practice guidelines. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89(6):924–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sing CW, Cheung CL, Wong IC. Pharmacogenomics‐‐how close/far are we to practising individualized medicine for children? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79(3):419–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Giri J, Curry TB, Formea CM, Nicholson WT, Rohrer Vitek CR. Education and knowledge in pharmacogenomics: still a challenge? Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;103(5):752–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Haga SB, Mills R, Moaddeb J, Allen LN, Cho A, Ginsburg GS. Primary care providers' use of pharmacist support for delivery of pharmacogenetic testing. Pharmacogenomics. 2017;18(4):359–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Blumenberg C, Barros AJD. Response rate differences between web and alternative data collection methods for public health research: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Public Health. 2018;63(6):765–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lauschke VM, Zhou Y, Ingelman‐Sundberg M. Novel genetic and epigenetic factors of importance for inter‐individual differences in drug disposition, response and toxicity. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;197:122–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhou Y, Fujikura K, Mkrtchian S, Lauschke VM. Computational methods for the Pharmacogenetic interpretation of next generation sequencing data. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rabbani B, Nakaoka H, Akhondzadeh S, Tekin M, Mahdieh N. Next generation sequencing: implications in personalized medicine and pharmacogenomics. Mol Biosyst. 2016;12(6):1818–1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Han SM, Park J, Lee JH, et al. Targeted next‐generation sequencing for comprehensive genetic profiling of pharmacogenes. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;101(3):396–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Search strategy for the study participants

Table S1. Perceived knowledge [n (%)] concerning which drug(s) a particular pharmacogenetic test is for

Table S2. Availability [n (%)] of pharmacogenetics tests in own laboratory for clinical use