Abstract

Background

Although the survival of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has improved, irreversible organ damage remains a critical concern. We aimed to characterize damage accrual and its clinical associations and causes of death in Swedish patients.

Methods

Accumulation of damage was evaluated in 543 consecutively recruited and well-characterized cases during 1998−2017. The Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC)/American College of Rheumatology damage index (SDI) was used to estimate damage.

Results

Organ damage (SDI ≥ 1) was observed in 59%, and extensive damage (SDI ≥ 3) in 25% of cases. SDI ≥ 1 was significantly associated with higher age at onset, SLE duration, the number of fulfilled SLICC criteria, neurologic disorder, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, depression and secondary Sjögren's syndrome (SS). In addition, SDI ≥ 3 was associated with serositis, renal and haematological disorders and interstitial lung disease. A multiple regression model identified not only well-known risk factors like APS, antihypertensives and corticosteroids, but pericarditis, haemolytic anaemia, lymphopenia and myositis as being linked to SDI. Malignancy, infection and cardiovascular disease were the leading causes of death.

Conclusions

After a mean SLE duration of 17 years, the majority of today's Swedish SLE patients have accrued damage. We confirm previous observations and report some novel findings regarding disease phenotypes and damage accrual.

Keywords: Damage accrual, immunosuppressants, mortality, SLE phenotypes, Sweden, systemic lupus erythematosus

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease with diverse clinical manifestations and an unpredictable disease course, often including periods of increased disease activity followed by remission. Long-standing inflammation, drug-related side effects and comorbidities may eventually cause permanent organ damage in many patients, and such acquired damage is tightly linked to mortality.1–3

Since the 1950s, the 5-year survival rate in SLE has increased significantly from approximately 50% to almost 95% in the 2000s.4,5 The improved survival rate has been linked to increased awareness, including identification of cases with milder disease, earlier diagnosis and more efficient clinical care.6 Yet age-related mortality remains significantly higher among patients with SLE compared to the general population, mainly due to disease activity, infections, thromboembolic events and cardio- or cerebrovascular disease.7–9 Despite progress in the understanding of SLE pathogenesis and development of more targeted therapies, data suggest that survival rates have plateaued since the mid-1990s.6,10 In addition, differences in accrual of damage and survival rates have been identified between high- and low-income countries, which may reflect diverse access to healthcare, the socio-economy and ethnicity.6, 11

The Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) and American College of Rheumatology (ACR) damage index (SDI) is the only validated tool to quantify accumulated irreversible organ damage.12 Attribution of organ damage to SLE is not mandatory. The SDI comprises 12 organ systems; damage that has occurred since the onset of SLE is recorded when it has persisted for 6 months.12 Absence of an SDI increase is a measure of well-controlled or mild disease ,3,13 whereas increasing SDI scores are associated with increased risk of further damage as well as a higher age-related risk of mortality.1,3,13,14 Furthermore, damage accrual has been associated with patient-reported outcome measures, such as quality of life and activity limitations.15

Several studies have identified risk factors for the development, or progression, of organ damage using the SDI but recent reports on the Swedish SLE population are lacking. The age at onset of SLE plays an important role for expression of disease manifestations and outcomes, including mortality risks.16 Late-onset SLE can be milder, but may nevertheless accumulate irreversible damage over time.16 Other factors associated with organ damage include disease duration, male gender, recurrent flares, hypertension, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) and the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL).17,18 Regarding treatments, use of cyclophosphamide and high accumulated doses of corticosteroids have been associated with higher SDI scores, whereas antimalarials seem to be protective.1,17,19,20 Given the heterogeneous clinical and immunological nature of SLE, in-depth knowledge of specific disease variables associated with accrual of damage and severe outcomes is indeed essential.

We primarily aimed to characterize accumulated organ damage and describe causes of death in two Swedish cohorts of well-characterized SLE cases. Secondly, we examined factors associated with damage accrual according to the SDI, including demographics, disease manifestations, medical therapies and autoantibody specificities.

Materials and methods

Cohorts

Swedish healthcare is public, tax-funded and offers universal access. This study was carried out in two separate geographical areas of Sweden. The University Hospital in Linköping serves the Östergötland region (n = 457,000) and Uppsala Akademiska Hospital serves the Uppsala region (n = 369,000) with rheumatological care. Five hundred and forty-three consecutively recruited and longitudinally followed SLE cases diagnosed at the rheumatology units in Linköping (n = 296) and Uppsala (n = 247) were included. The Linköping cohort was launched in 2008 and has previously been described in detail.21 It includes more than 95% of the expected SLE cases in Linköping and ≥98% of all known SLE cases in the region.22 The Uppsala cohort was launched in 1998 and has an estimated coverage of 84% in the area.23 All patients met the 1982 ACR (ACR-82) and/or 2012 SLICC classification criteria (SLICC-12),24,25 and were included as prevalent or incident cases until 31 December 2017.

Variables

Background variables such as age, gender, ethnicity, disease duration and age at diagnosis were available for all cases from SLE diagnosis to 31 December 2017, or death. The numbers of fulfilled ACR-82 and SLICC-12 criteria, as well as data on smoking habits (ever/never) were recorded at the data extraction time point in each cohort. Clinical data on APS, secondary Sjögren's syndrome (SS), lymphoma and comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, interstitial lung disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, depression, myositis and hypothyroidism were collected through review of medical records (definitions in Supplementary Table 1). Cause of death was recorded according to death certificates.

The use of antirheumatic drugs, including antimalarials and other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, glucocorticoids, biologics (rituximab and belimumab), antihypertensives, statins, levothyroxine and antidepressants were registered. Damage accrual was evaluated at the end of 2017 using the SDI, including detailed information on organ damage in each separate domain.12 In accordance with Gonçalves et al.,26 comparisons of cases without damage (SDI = 0) and with damage (SDI ≥ 1), as well as with extensive damage (SDI ≥ 3) were performed. In addition, we evaluated time to first and second damage in relation to each variable.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between groups, for example, cases without damage (SDI = 0) vs. cases with damage (SDI ≥ 1) or cases with extensive damage (SDI ≥ 3), were performed for frequency distributions and measures on interval-/ratio scales. Comparisons of frequency distributions were performed using chi-square tests of homogeneity (or Fisher's exact test when assumptions were not fulfilled) with the phi coefficient as a measure of effect size (ES). The comparisons of measures on interval-/ratio scales were performed using independent t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests (when assumptions were not fulfilled) with r as a measure of ES. Comparisons between groups with different SDI scores and disease duration were carried out with the Kruskal–Wallis test.

The associations between variables and organ damage (SDI ≥ 1) were examined using Poisson regression. First, univariate associations were examined in simple Poisson regression models. All variables in Table 1 (except for diabetes and interstitial lung disease/pulmonary fibrosis since they constitute parts of the SDI) as well as subgroups of ACR-82 and SLICC-12 were included in the analysis. Second, associations were examined while controlling for age at diagnosis and disease duration (each variable was tested for, while also including age at diagnosis and disease duration in the model). Finally, all variables showing univariate associations with organ damage were combined in a multiple Poisson regression model followed by backward elimination of non-significant variables.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 543 systemic lupus erythematosus cases

| Background variables (n = cases with available data) | Total (n = 543) | Linköping (n = 296) | Uppsala (n = 247) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females, n (%) | 465 (85.6%) | 254 (85.8%) | 211 (85.4%) | NS |

| Caucasian ethnicity, n (%) | 491 (90.4%) | 260 (87.8%) | 231 (93.5%) | 0.04 |

| Ever smoker (former or current), n (%) n = 524 | 215 (41.0%) | 125 (44.5%) | 90 (37.0%) | NS |

| Deceased at time point for data extraction, n (%) | 54 (9.9%) | 31 (10.5%) | 23 (9.3%) | NS |

| Disease variables | ||||

| Age at diagnosis, mean years (range years) | 36.6 (3–85) | 39.7 (3–85) | 32.8 (3–78) | <0.0001 |

| Disease duration, mean years (range years) | 16.7 (0–63) | 15.5 (0–55) | 18.1 (0–63) | 0.02 |

| Recent-onset disease (diagnosis 2017) | 24 (4.4%) | 21 (7.1%) | 3 (1.2%) | 0.002 |

| Meeting ACR-82 criteria, n (%) | 491 (90.4%) | 252 (85.1%) | 239 (96.8%) | <0.0001 |

| Meeting SLICC-12 criteria, n (%) | 523 (96.3%) | 282 (95.3%) | 241 (97.6%) | NS |

| Number of fulfilled ACR-82 criteria, mean (range) | 5.2 (3–10) | 4.8 (3–9) | 5.7 (3–10) | <0.0001 |

| Number of fulfilled SLICC-12 criteria, mean (range) | 6.5 (3–14) | 6.0 (3–13) | 7.1 (3–14) | <0.0001 |

| SLICC/ACR damage index, mean (range) | 1.7 (0–11) | 1.8 (0–11) | 1.7 (0–11) | NS |

| Clinical SLE phenotypes (ACR-82 defined), n (%) | ||||

| 1) Malar rash | 292 (53.8%) | 118 (39.9%) | 174 (70.4%) | <0.0001 |

| 2) Discoid rash | 108 (19.9%) | 49 (16.6%) | 59 (23.9%) | 0.04 |

| 3) Photosensitivity | 318 (58.6%) | 150 (50.7%) | 168 (68.0%) | <0.0001 |

| 4) Oral ulcers | 111 (20.4%) | 36 (12.2%) | 76 (30.8%) | <0.0001 |

| 5) Arthritis | 406 (74.8%) | 223 (75.3%) | 183 (74.1%) | NS |

| 6) Serositis | 211 (38.9%) | 112 (37.8%) | 99 (40.1%) | NS |

| 7) Renal disorder | 156 (28.7%) | 82 (27.7%) | 74 (30.0%) | NS |

| 8) Neurologic disorder | 35 (6.4%) | 16 (5.4%) | 19 (7.7%) | NS |

| 9) Haematologic disorder | 342 (63.0%) | 180 (60.8%) | 162 (65.6%) | NS |

| 10) Immunologic disorder | 324 (60.0%) | 160 (54.1%) | 164 (66.4%) | 0.005 |

| 11) Antinuclear antibody (IF-ANA)a | 535 (98.5%) | 292 (98.6%) | 243 (98.4%) | NS |

| Serology, n (%) | ||||

| Anti-dsDNA antibody (anti-dsDNA), n = 542 | 300 (55.4%) | 148 (50.0%) | 152 (61.8%) | 0.009 |

| Anti-Smith antibody (anti-Sm), n = 542 | 58 (10.7%) | 21 (7.1%) | 37 (15.0%) | 0.005 |

| Anti-Sjögren's syndrome A (Ro/SSA), n = 542 | 238 (43.9%) | 118 (39.9%) | 120 (48.8%) | NS |

| Anti-Sjögren's syndrome A (Ro52/TRIM21), n = 541 | 191 (35.3%) | 104 (35.1%) | 87 (35.5%) | NS |

| Anti-Sjögren's syndrome A (Ro60), n = 519 | 218 (42.0%) | 108 (39.3%) | 110 (45.1%) | NS |

| Anti-Sjögren's syndrome B (La/SSB), n = 542 | 140 (25.8%) | 84 (28.4%) | 56 (22.8%) | NS |

| Anti-snRNP, n = 542 | 181 (33.4%) | 106 (35.8%) | 75 (30.5%) | NS |

| aPLb, n = 535 | 260 (48.6%) | 163 (55.1%) | 97 (40.1%) | 0.0003 |

| Lupus anticoagulant, n = 457 | 117 (25.6%) | 77 (31.0%) | 39 (18.7%) | 0.005 |

| Low complement, n = 525 | 309 (58.6%) | 149 (50.5%) | 160 (69.6%) | 0.001 |

| Treatment, at last visit, n (%) | ||||

| Antimalarials, n = 541 | 342 (63.2%) | 198 (66.9%) | 144 (58.8%) | 0.05 |

| Glucocorticoids, n = 537 | 344 (64.1%) | 194 (65.5%) | 150 (62.2%) | NS |

| Methotrexate, n = 541 | 40 (7.4%) | 23 (7.8%) | 17 (6.9%) | NS |

| Cyclosporine/sirolimus, n = 539 | 12 (2.2%) | 10 (3.4%) | 2 (0.8%) | NS |

| Azathioprine, n = 541 | 65 (12.0%) | 20 (6.8%) | 45 (18.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil, n = 541 | 74 (13.7%) | 39 (13.2%) | 35 (13.9%) | NS |

| Antihypertensives, n = 543 | 259 (47.7%) | 149 (50.3%) | 110 (44.5%) | NS |

| Statins, n = 543 | 86 (15.8%) | 56 (18.9%) | 30 (12.1%) | 0.04 |

| Treatment, ever, n (%) | ||||

| Cyclophosphamide, n = 536 | 119 (22.2%) | 42 (14.2%) | 77 (32.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Biologics, n = 530 | 73 (13.8%) | 56 (18.9%) | 17 (7.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Levothyroxine treatment, n = 513 | 82 (16.0%) | 45 (15.3%) | 37 (17.4%) | NS |

| Antidepressants, n = 496 | 99 (18.2%) | 40 (13.5%) | 59 (29.5%) | 0.003 |

| Comorbidites, n (%) | ||||

| Raynaud, n = 532 | 165 (31.0%) | 73 (24.7%) | 92 (39.0%) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes mellitusc, n = 543 | 30 (5.5%) | 17 (5.7%) | 13 (5.3%) | NS |

| Lymphomac, n = 533 | 9 (1.7%) | 2 (0.7%) | 7 (3.0%) | NS |

| SSc, n = 536 | 129 (24.1%) | 64 (21.3%) | 65 (27.1%) | NS |

| Interstitial lung diseasec, n = 520 | 17 (3.3%) | 10 (3.4%) | 7 (3.1%) | NS |

| Myositisc, n = 518 | 10 (1.9%) | 3 (1.0%) | 7 (3.2%) | NS |

| APSc, n = 542 | 91 (16.8%) | 60 (20.3%) | 31 (12.6%) | 0.02 |

| Combined APS and SS, n = 535 | 18 (3.4%) | 13 (4.4%) | 5 (2.1%) | NS |

Positive by immunofluorescence microscopy.

Defined according to immunological SLICC classification criterion.

See supplementary table for definitions.

ACR: American College of Rheumatology; aPL: antiphospholipid antibodies; APS: antiphospholipid antibody syndrome; NS: not significant; SLICC: Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics; snRNP: small nuclear ribonucleoproteins; SS: secondary Sjögren's syndrome.

P-values < 0.05 were considered significant, but since this is an exploratory study, significances should be interpreted in association with the reader's knowledge of what hypotheses can be posed (it would not be possible to list every hypothesis for each association examined in this study). For informative purposes, the exact p-values are provided.

Ethics

Oral and/or written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study protocols were approved by the regional ethics review boards in Linköping (M75-08/2008) and Uppsala (2016/155 EPN Uppsala 00-227).

Results

As postulated in Table 1, mean age at diagnosis was 37 years, mean disease duration at data extraction was 17 years and 86% were women. More than 90% of patients were of Caucasian ethnicity whereas the majority of the remainder of patients were Asian, Hispanic or Middle Eastern in origin. The SLE duration of non-Caucasian patients was significantly shorter compared with Caucasians (11 vs. 17 years, p = 0.0006). The majority of cases had an established disease at data extraction (31 December 2017) and only 4% had recent-onset SLE with less than 1 year's disease duration. The most common ACR-82 criterion was arthritis (75%), followed by haematologic disorder (63%), photosensitivity (59%) and malar rash (54%). Renal involvement (ACR-82) was observed in 29% and neurologic disorder (ACR-82) in 6% of cases. A positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) test was detected in 99% and aPL (SLICC-12) in 49% of patients at least once during their disease course.

When comparing the cohorts of Linköping and Uppsala, gender, percentage of fulfilled SLICC-12 criteria and the mean SDI scores as well as the majority of clinical manifestations, including renal and neurological involvement, were similar (Table 1). The Uppsala cohort comprised more cases with malar rash, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, anti-dsDNA and anti-Sm. The Linköping cohort included older patients with shorter disease duration and had a lower percentage of cases meeting ACR-82, whereas the presence of aPL and APS was more frequent compared to Uppsala (Table 1). However, as the differences between the cohorts were considered negligible further statistical analyses were performed on merged data.

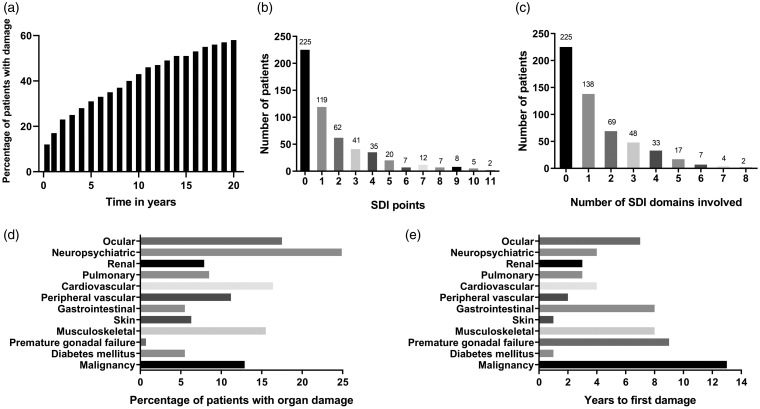

In total, the study population consisted of 543 patients, of whom the majority had accrued damage from SLE onset and onwards (Figure 1a). At the time point of data extraction, 59% (n = 318) had accrued ‘any damage’ (SDI>0; Figure 1b). Among the 318 cases with any damage, extensive damage with an SDI score of ≥3 (n = 137, 25%, mean disease duration 26 years) was most common, followed by an SDI score of 1 (n = 119, 22%, mean disease duration 14 years) and an SDI score of 2 (n = 62, 11%, mean disease duration 19 years, p < 0.0001). Subsequently, involvement of one organ domain (n = 138, 25%) was most common, but some individuals were affected by severe impairment involving several domains (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Figure 1a indicates the accumulation of organ damage in the study population from SLE onset and onwards. Figure 1b shows the distribution of points according to the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology damage index (SDI), whereas 1c illustrates number of involved SDI domains. Figure 1d demonstrates the frequencies (%) of involved separate organ domains in all 543 cases. Figure 1e presents the median time to the first damage in relation to organ domain involvement.

The distribution of damage in each organ domain is demonstrated in Figure 1d. Of patients with SDI ≥ 1, involvement of the neuropsychiatric (25%), ocular (18%), cardiovascular (16%), musculoskeletal (16%) and malignancy (13%) domains were most prevalent (Figure 1d). A binary comparison of damage vs. no damage in these five most commonly affected organ domains did not identify further variables of predictive importance.

Figure 1e illustrates time to first damage for each separate domain. The skin domain (median time 9 months) and diabetes mellitus (12 months) showed shortest time from SLE onset to first damage, followed by peripheral vascular (2 years), renal and pulmonary domains (both 3 years). The malignancy domain had the longest time to first damage (median time 13 years). Time to first damage was shorter for men compared with women (median 2 vs. 6 years, p < 0.001) and for lupus anticoagulant (LA) positive patients compared with LA negatives (median 3 vs. 6 years, p = 0.005). APS was borderline significant (median 4 vs. 5 years, p = 0.07) and cases with combined APS/SS did not significantly differ in time to first damage compared with the others (p = 0.75). Conversely, time to first damage was longer for anti-La/SSB antibody positive patients (median 8 years vs. 4 years, p = 0.006), patients with malar rash (7 years vs. 3 years, p < 0.001) and patients treated with levothyroxine (10 vs. 4 years, p = 0.002) or antidepressants (8 vs. 4 years, p = 0.03). Second damage was acquired earlier in cases who were deceased at the time of data extraction (9 vs. 14 years, p = 0.03) and for those who had been treated with biologics (8 vs. 14 years, p = 0.02). A positive LA test almost met statistical significance regarding earlier second damage (10 vs. 14 years, p = 0.06). Patients with malar rash showed longer disease duration until second damage (15 years vs. 10 years, p = 0.009).

Patients with SDI ≥ 1 were older at diagnosis (mean age 39 vs. 33 years), had a longer disease duration (mean 20 vs. 12 years), were of Caucasian ethnicity (93% vs. 87%) and fulfilled a higher number of SLICC-12 criteria (6.7 vs. 6.2) (Table 2). Similarly, neurologic disorder (SLICC-12), aPL (SLICC-12), positive IgG anti-β2-glycoprotein-I, positive LA test as well as APS, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, depression and SS were more common in patients with any damage (Table 2). At follow-up, all 18 patients with combined APS/SS had accrued damage and a majority (n = 11) of these cases had extensive damage (SDI ≥ 3). A positive anti-La/SSB antibody test was associated with absence of damage. Regarding therapies, cyclophosphamide, ciclosporin and mycophenolate mofetil were more commonly used in patients with acquired damage, whereas ongoing antimalarial therapy was less frequent (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic, clinical characteristics and medication in SLE cases with and without organ damage

| Feature | Patients without damage, SDI = 0 (n = 225) | Patients with damage, SDI ≥ 1 (n = 318) | P-value | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background variables (n = cases with data available) | ||||

| Females, n = 543 | 201 (89.3%) | 264 (83.0%) | 0.05 | |

| Age at diagnosis (mean years, SD) | 33.4 ± 15.2 | 38.8 ± 18.3 | <0.001 | 0.16 |

| Disease duration (mean years, SD) | 11.6 ± 8.9 | 20.3 ± 12.7 | <0.001 | 0.37 |

| Caucasians, n = 543 | 195 (86.7%) | 296 (93.1%) | 0.02 | 0.11 |

| Ever smoker, n = 524 | 82 (37.6%) | 133 (43.5%) | 0.2 | |

| Number of SLICC-12 criteria | 6.2 ± 2.0 | 6.7 ± 2.2 | 0.008 | 0.12 |

| Number of ACR-82 criteria | 5.2 ± 1.5 | 5.3 ± 1.5 | 0.4 | |

| Clinical phenotypes (ACR-82 definitions) | ||||

| Malar rash, n = 543 | 110 (48.9%) | 182 (57.2%) | 0.07 | |

| Discoid rash, n = 543 | 37 (16.4%) | 71 (22.3%) | 0.1 | |

| Photosensitivity, n = 543 | 137 (60.9%) | 181 (56.9%) | 0.4 | |

| Oral ulcers, n = 543 | 47 (20.9%) | 64 (20.1%) | 0.9 | |

| Arthritis, n = 543 | 171 (76.0%) | 235 (73.9%) | 0.7 | |

| Serositis, n = 543 | 76 (33.8%) | 135 (42.5%) | 0.05 | |

| Renal disorder, n = 543 | 60 (26.7%) | 96 (30.2%) | 0.4 | |

| Neurologic disorder, n = 543 | 7 (3.1%) | 28 (8.8%) | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Haematologic disorder, n = 543 | 136 (60.4%) | 206 (64.8%) | 0.4 | |

| Immunologic disorder, n = 543 | 135 (60.0%) | 189 (59.4%) | 1.0 | |

| ANA, n = 543 | 221 (98.2%) | 314 (98.7%) | 0.2† | |

| Immunoserology | ||||

| aPL, n = 535 | 90 (40.7%) | 170 (54.1%) | 0.003 | 0.13 |

| aCL IgG, n = 523 | 47 (22.0%) | 83 (26.9%) | 0.2 | |

| aCL IgM, n = 489 | 22 (10.8%) | 37 (12.9%) | 0.6 | |

| β2GP1 IgG, n = 506 | 29 (14.1%) | 68 (22.7%) | 0.02 | 0.11 |

| β2GP1 IgM, n = 371 | 17 (10.7%) | 24 (11.3%) | 1.0 | |

| RF, n = 301 | 30 (22.9%) | 50 (29.4%) | 0.3 | |

| Ro/SSA, n = 542 | 101 (44.9%) | 137 (43.2%) | 0.8 | |

| La/SSB, n = 542 | 69 (30.7%) | 71 (22.4%) | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| Anti-snRNP, n = 542 | 72 (32.4%) | 108 (34.1%) | 0.8 | |

| Low complement, n = 525 | 133 (60.5%) | 176 (57.7%) | 0.6 | |

| Direct Coombs' test, n = 267 | 45 (41.3%) | 74 (46.8%) | 0.4 | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension, n = 543 | 72 (32.0%) | 187 (58.8%) | <0.001 | 0.26 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n = 543 | 16 (7.1%) | 70 (22.0%) | <0.001 | 0.20 |

| Hypothyroidism, n = 513 | 28 (13.1%) | 54 (18.1%) | 0.2 | |

| Depression, n = 496 | 31 (14.9%) | 68 (23.6%) | 0.02 | 0.11 |

| Other characteristics | ||||

| Interstitial lung disease, n = 520 | 3 (1.4%) | 14 (4.6%) | 0.08 | |

| Lupus anticoagulant, n = 457 | 36 (18.8%) | 81 (30.6%) | 0.006 | 0.13 |

| Lymphoma, n = 533 | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (2.9%) | ∞ | |

| SS, n = 536 | 38 (17.0%) | 91 (29.2%) | 0.002 | 0.14 |

| APS, n = 542 | 12 (5.4%) | 79 (24.8%) | <0.001 | 0.26 |

| Combined APS and SS, n = 535 | 0 (0%) | 18 (3.4%) | ∞ | |

| Myositis, n = 518 | 5 (2.3%) | 5 (1.6%) | 0.2† | |

| Raynaud, n = 532 | 72 (32.1%) | 93 (30.2%) | 0.7 | |

| Antirheumatic treatment at last visit | ||||

| Antimalarials, n = 541 | 174 (77.7%) | 168 (53.0%) | <0.001 | 0.25 |

| Corticosteroids, n = 537 | 141 (63.5%) | 203 (64.4%) | 0.9 | |

| Other immunosuppressant drugs | ||||

| Azathioprine, n = 541 | 22 (9.8%) | 42 (13.6%) | 0.2 | |

| Biologics* (rituximab/belimumab), n = 543 | 29 (12.9%) | 44 (13.8%) | 0.9 | |

| Cyclophosphamide*, n = 536 | 28 (12.7%) | 91 (28.9%) | <0.001 | 0.19 |

| Ciclosporin, n = 539 | 1 (0.4%) | 11 (3.5%) | 0.01† | 0.10 |

| Methotrexate, n = 541 | 17 (7.6%) | 23 (7.3%) | 1.0 | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil, n = 541 | 22 (9.8%) | 52 (16.4%) | 0.04 | 0.09 |

ACR: American College of Rheumatology; ANA: antinuclear antibodies; aCL: anticardiolipin; aPL: antiphospholipid antibodies; APS: antiphospholipid antibody syndrome; β2GP1: beta-2-glycoprotein-1; RF: rheumatoid factor; SD: standard deviation; SLICC: Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics; SS: secondary Sjögren's syndrome.

Fisher's exact test.

Medication ever.

We further compared patients with extensive damage to those without any damage. All significant variables in the comparison of no damage vs. any damage (Table 2) remained significantly associated with extensive damage (Table 3). In addition, IgG anticardiolipin, serositis, haematological and renal disorders, and interstitial lung disease were associated with extensive organ damage (Table 3).

Table 3.

Demographic, clinical characteristics and medication in cases without and with severe damage

| Feature | Patients without damage, SDI = 0 (n = 225) | Patients with damage, SDI ≥ 3 (n = 137) | P-value | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background variables (n = cases with data available) | ||||

| Age at diagnosis (mean years, SD) | 33.4 ± 15.2 | 39.7 ± 19.6 | 0.002 | 0.20 |

| Disease duration (mean years, SD) | 11.6 ± 8.9 | 25.8 ± 12.5 | <0.001 | 0.62 |

| Caucasians, n = 363 | 195 (86.7%) | 132 (96.4%) | 0.005 | 0.16 |

| Number of SLICC-12 criteria | 6.2 ± 2.0 | 7.2 ± 2.2 | <0.001 | 0.26 |

| Clinical phenotypes (ACR-82 definitions) | ||||

| Serositis, n = 363 | 76 (33.8%) | 67 (48.9%) | 0.006 | 0.15 |

| Renal disorder, n = 363 | 60 (26.7%) | 51 (37.2%) | 0.05 | 0.11 |

| Haematologic disorder, n = 363 | 136 (60.4%) | 100 (73.0%) | 0.02 | 0.13 |

| Immunoserology | ||||

| aPL, n = 357 | 90 (40.7%) | 85 (63.0%) | <0.001 | 0.22 |

| aCL IgG, n = 350 | 47 (22.0%) | 44 (32.8%) | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| β2GP1 IgG, n = 339 | 29 (14.1%) | 33 (25.2%) | 0.02 | 0.14 |

| La/SSB, n = 362 | 69 (30.7%) | 22 (16.2%) | 0.003 | 0.16 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension, n = 363 | 72 (32.0%) | 107 (78.1%) | <0.001 | 0.45 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n = 363 | 16 (7.1%) | 47 (34.3%) | <0.001 | 0.35 |

| Depression, n = 331 | 31 (14.9%) | 36 (29.5%) | 0.002 | 0.18 |

| Interstitial lung disease, n = 348 | 3 (1.4%) | 12 (9.0%) | 0.002 | 0.18 |

| Other characteristics | ||||

| APS, n = 362 | 12 (5.4%) | 46 (33.6%) | <0.001 | 0.37 |

| Lupus anticoagulant, n = 307 | 36 (18.8%) | 36 (31.6%) | 0.02 | 0.15 |

| SS, n = 359 | 38 (17.0%) | 37 (27.8%) | 0.02 | 0.13 |

| Combined APS and SS, n = 535 | 0 (0%) | 11 (2.1%) | ∞ | |

ACR: American College of Rheumatology; aCL: anticardiolipin; aPL: antiphospholipid antibodies; APS: antiphospholipid antibody syndrome; β2GP1: beta-2-glycoprotein-1; SD: standard deviation; SLICC: Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics; SS: secondary Sjögren's syndrome

Next, we performed regression analyses with the quantitative global SDI score at data extraction. In the first univariate Poisson model, a number of factors (n = 52) were significantly associated with organ damage. However, the number of significant variables was reduced (n = 43) when we adjusted for age and disease duration. Table 4 shows only factors with a significant impact on SDI scores in all models plus gender, ethnicity, LA, antimalarial therapy and combined APS/SS as some of these variables have previously been associated with damage accrual.1,17,27 In the final model, age at diagnosis, SLE duration, pericarditis, haemolytic anaemia, lymphopenia, neurologic disorder, antihypertensive treatment, statin treatment, APS, myositis, cyclophosphamide treatment (ever), daily prednisolone ≥ 7,5mg (ongoing) and ciclosporin treatment (ongoing) remained as independent risk factors (Table 4). Pericarditis is indeed included in the cardiovascular domain of SDI, but only 4 out of 150 patients in our study population who fulfilled the ACR-82 pericarditis criterion, were recorded as irreversible damage. The overall pseudo R2 was 0.517, indicating that > 50% of the total variation of global SDI scores can be explained by the factors included in the multiple model. Male gender and LA positivity were significant in the univariate models but did not remain so in the multiple model. Similarly, ongoing antimalarial therapy showed a protective effect in the univariate models only.

Table 4.

Poisson regression models to establish empirical relations with organ damage accrual (global SDI score)

| Univariate models |

Controlling for age at diagnosis and disease

duration |

Multiple model

(n = 471) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR* | 95% CI | Pseudo R2 | OR | 95% CI | ΔPseudo R2† | OR | 95% CI | |

| Gender | 1.26 | 1.07–1.50 | 0.004 | 1.30 | 1.09–1.55 | 0.005 | ||

| Age at diagnosis | 1.01 | 1.01–1.01 | 0.024 | – | – | 1.05 | 1.04–1.06 | |

| Disease duration | 1.04 | 1.04–1.05 | 0.193 | – | – | 1.03 | 1.03–1.04 | |

| Caucasian origin | 2.36 | 1.72–3.24 | 0.024 | 1.21 | 0.87–1.68 | |||

| Pericarditis | 1.49 | 1.30–1.70 | 0.023 | 1.34 | 1.18–1.54 | 0.015 | 1.29 | 1.11–1.51 |

| Haemolytic anaemia | 1.76 | 1.46–2.12 | 0.020 | 1.83 | 1.51–2.20 | 0.030 | 1.71 | 1.35–2.16 |

| Lymphopenia | 1.40 | 1.23–1.60 | 0.017 | 1.46 | 1.28–1.66 | 0.028 | 1.18 | 1.02–1.37 |

| Neurologic disorder (SLICC-12 defined) | 1.70 | 1.44–2.01 | 0.071 | 1.59 | 1.35–1.88 | 0.024 | 1.35 | 1.13–1.62 |

| Antihypertensives (ongoing) | 2.77 | 2.41–3.20 | 0.145 | 1.75 | 1.50–2.04 | 0.049 | 1.35 | 1.13–1.63 |

| Statins (ongoing) | 2.67 | 2.33–3.06 | 0.116 | 1.60 | 1.39–1.85 | 0.035 | 1.41 | 1.20–1.66 |

| Antidepressants# | 1.51 | 1.30–1.76 | 0.154 | 1.32 | 1.13–1.53 | 0.010 | 1.40 | 1.18–1.66 |

| APS | 2.17 | 1.89–2.50 | 0.072 | 1.65 | 1.43–1.91 | 0.041 | 1.56 | 1.33–1.82 |

| Myositis | 1.71 | 1.18–2.47 | 0.075 | 1.87 | 1.29–2.70 | 0.006 | 1.74 | 1.14–2.67 |

| Cyclophosphamide# | 1.86 | 1.63–2.13 | 0.065 | 1.93 | 1.67–2.23 | 0.073 | 1.56 | 1.31–1.85 |

| Daily prednisolone dose ≥ 7.5mg (ongoing) | 1.49 | 1.29–1.71 | 0.037 | 1.64 | 1.42–1.88 | 0.041 | 1.40 | 1.19–1.64 |

| Antimalarials (ongoing) | 0.41 | 0.36–0.47 | 0.125 | 0.67 | 0.58–0.77 | 0.029 | ||

| Ciclosporin (ongoing) | 1.78 | 1.28–2.48 | 0.020 | 1.52 | 1.09–2.13 | 0.002 | 1.69 | 1.18–2.40 |

| Lupus anticoagulant | 1.36 | 1.16–1.58 | <0.001 | 1.64 | 1.36–1.98 | 0.014 | ||

| Combined APS and SS | 2.47 | 1.94–3.14 | 0.058 | 1.47 | 1.15–1.87 | 0.005 | ||

| Total Pseudo R2 (multiple model) | 0.517 | |||||||

Note: Pseudo R2 is different from the R2 used in ordinary least-squares regression models. However, it will give an approximation of how well the independent variables are related with the outcome (sum of global SDI).

Univariate models test for univariate relations and those were also tested for while controlling for age at diagnosis and disease duration. Factors significantly associated with damage accrual (when controlling for age at diagnosis and disease duration) were combined into a multiple model where factors were stepwise removed until there were only factors with p < 0.05 remaining.

Shows the explanatory value after age at diagnosis and disease duration has been considered: age at diagnosis and disease duration had together pseudo R2 = 0.32.

Medication ever.

The odds ratios (OR) can be interpreted as follows: an increase of 1 year of disease duration is associated with a 4% higher score (OR = 1.04) in the number of SDI points, and ongoing treatment with antimalarials in the legend is associated with a 59% lower score (OR = 0.41, 1 − 0.41 = 0.59) in the sum of global SDI score compared to those not having ongoing treatment with HCQ. Variables entered into the multiple model, before backward deletion, were all variables shown in Table 1, including subgroups of the ACR criteria

ACR: American College of Rheumatology; APS: antiphospholipid antibody syndrome; CI: confidence interval; SLICC: Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics; SS: secondary Sjögren's syndrome.

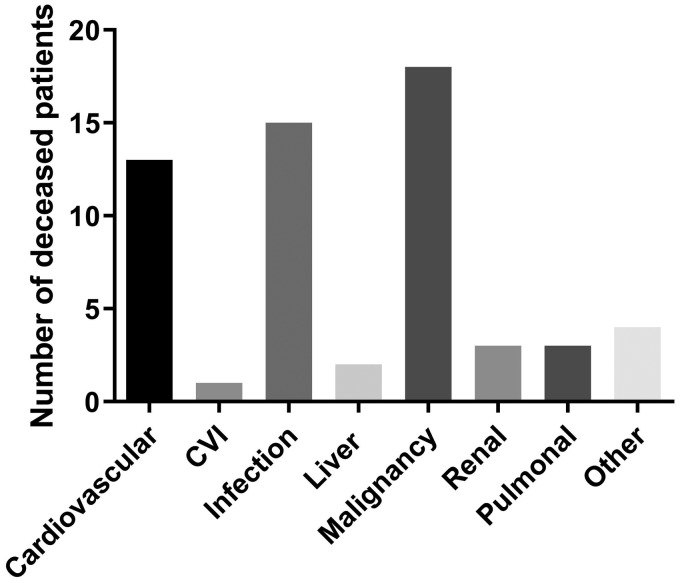

At the end of follow-up, 54 patients (10%) were deceased, 7 of which were included in our cohorts as incident cases. Ten of the 54 cases died before the age of 60, including five from malignancies. The mean age at death among the 54 cases was 70 years (range 27–96) and the mean SLE duration was 20 years (range 2–63). The causes of death are presented in Figure 2. Malignancy (n = 18; whereof five were haematological malignancies and five lung cancer) was the leading cause of death, followed by infections and cardiovascular disease. The deceased cases had a significantly higher SDI score compared with patients alive at follow-up (SDI 5.3 vs. 1.3, p < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Cause of death according to death certificates among the 54 deceased cases at the time point of data extraction (31 December 2017). CVI: cerebrovascular insult.

Discussion

In this Swedish SLE population with a mean disease duration of 17 years, more than half of the cases (59%) had acquired organ damage involving at least one organ domain. Studies of European populations with comparable follow-up and a similar distribution of ethnicity have shown a prevalence of organ damage between 36 and 69%.14,18,26,28 In the SLICC cohort, including patients with approximately 50% Caucasian ethnicity, 51% were already presenting with organ damage after 6 years' disease duration.1 The corresponding percentage in the present study in the sixth year was 38%, and this is essentially in line with older observations from Sweden (Lund University), Spain and the United Kingdom.9,13,14

The most frequently affected organ domains among the Swedish SLE cases herein were the neuropsychiatric, ocular, cardiovascular, musculoskeletal and malignancy domains. Similar results were found in a Portuguese study26 with exceptions including higher frequencies of pulmonary, renal and musculoskeletal damage, whereas malignancies and cardiovascular damage were slightly more common in our study. Divergent findings could reflect genetic variation as well as differences in coverage of the study population, a shorter follow-up time, and the cross-sectional design of the Portuguese study.

As previously shown by others, we demonstrate that age, disease duration and a higher number of fulfilled ACR-82 classification criteria are associated with global damage.9,18,19,26 As the SDI does not demand attribution to SLE, factors like comorbidities and increased susceptibility to drug adverse effects in the elderly are also of importance. One should bear in mind that certain types of damage, such as osteoporosis, cataracts and cerebrovascular accident, in general are more common in the older population and may thus not only be explained by raised activity, long disease duration or corticosteroid side-effects.1

Persistent proteinuria and/or renal disorder have been associated with a more aggressive SLE.4,9,11 17,26 This was confirmed here, as renal disorder was more common in patients with extensive damage compared to patients without damage. Patients with African-American, Asian and Hispanic heritage have been shown to be afflicted by damage earlier during their disease course than other ethnicities, and they also have an increased risk of renal involvement and a worse outcome overall.17,29,30 Although socio-economics can contribute, increased genetic burden and a higher number of ANA subspecificities may contribute to more severe disease phenotypes in non-Caucasians.17,29,31 However, differences with regard to ethnicity were not observed in the present study. Possibly, this could be explained by the longer SLE duration of Caucasians as well as by the low percentage of non-Caucasians included, albeit comparable with the numbers of other Scandinavian cohorts.32,33

Antidepressant therapy was more prevalent in patients with any damage as well as extensive damage and remained a risk factor in the multiple regression model. Whether this is directly related to SLE, or if it constitutes a consequence of high disease burden, remains to be clarified. Furthermore, SS was more frequent among patients with any damage and extensive damage, which is in line with the observation by Gonçalves et al.26 Similar to our findings, a frequency of approximately 20% of SS in SLE has been reported.34,35 One study observed worse outcomes including more damage and increased mortality in patients with additional autoimmune diseases, such as SS.27 In addition, SS was shown to be more common among Caucasians than among other ethnicities.27 These results corroborate our observation of considerable organ impairment in SLE cases with combined APS and SS. Importantly however, hypothyroidism was not associated with damage in the present study. With La/SSB and aPL as exceptions, we did not identify associations between damage accrual and specific autoantibodies, which corroborates most previous observations.1,18,28,36 Thus, we could not confirm the association between damage accrual and anti-dsDNA that was reported from the Hopkins Lupus cohort.17

In the multiple regression model, well established risk factors such as APS and hypertension were associated with damage accrual.9,11,26 Antihypertensive therapy could also be a proxy for nephritis as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors are renoprotective and are used to reduce proteinuria. Regarding SLE manifestations, we identified haemolytic anaemia, lymphopenia, neurologic disorder (SLICC-12), pericarditis and myositis to be significantly associated with global SDI scores (Table 4). Neurologic involvement has been suggested as a risk factor for damage, but the other manifestations described above (haemolytic anaemia, lymphopenia, pericarditis and myositis) have not been, to our knowledge, previously reported in association with SDI.26 Myositis in SLE has been associated with a more active disease, which could explain the association with SDI.37 In addition, haematological disorder, interstitial lung disease, serositis and aPL (IgG anticardiolipin, anti-β2-glycoprotein-I and LA) were more common among patients with extensive organ damage (Table 3). Possibly, this could reflect the frequent and long-term usage of high doses of corticosteroids in manifestations such as severe cytopenias, serositis and pulmonary involvement where other immunosuppressants occasionally may be insufficient.38,39 Regarding antirheumatic drugs, cyclophosphamide and corticosteroid doses corresponding to ≥7.5 mg prednisolone daily (at last visit) as well as ciclosporin were significant in the multiple regression model for SDI (Table 4). It is conceivable that drugs like cyclophosphamide and ciclosporin are more commonly used in patients with severe lupus (e.g. neuropsychiatric involvement or proliferative nephritis) or as a late alternative treatment in cases who have already acquired damage. An association between use of cyclophosphamide and SDI has been reported, and premature gonadal failure can also be a consequence of this treatment.19

Use of antimalarials was associated with absence of damage (Table 2) and was potentially protective against accrual of damage (Table 4), which is in line with observations of other studies.1,40 Antimalarials remain the cornerstone of SLE treatment since they not only reduce flares and are efficient for skin and joint manifestations, but they also improve the blood lipid profile and glucose levels, as well as contributing to antithrombotic effects.41 A Canadian study showed a stronger cholesterol-lowering effect of antimalarials in steroid-treated patients, and other authors have reported lower incidence of osteoporosis following use of antimalarials.42,43 However, patients with highly active or severe SLE are more likely to receive glucocorticoids and other immunosuppressants in addition to antimalarials, whereas the milder cases are more likely to receive antimalarials as monotherapy (i.e. confounding by indication). In this cohort, only 63% of the patients were still taking antimalarials at last visit. As antimalarials are important for inhibiting interferon-signalling in SLE, it will be important to develop alternative treatments for patients unable to tolerate hydroxychloroquine in order to target this pathway and reduce the long-term risk of damage accrual.1,2,40

As previously demonstrated, our data support that male gender and a positive LA test are associated with a shorter time to first damage.28,44 Somewhat surprisingly, diabetes was among the domains with shortest time to first damage. One reason for this could be the increased attention due to the SLE diagnosis, which is often followed by consecutive blood and urine sampling, combined with high doses of glucocorticoids during the first year of disease. The reason for a significantly longer time to first damage in patients with malar rash, depression, hypothyreosis and La/SSB antibodies is not apparent but these factors may constitute markers of milder disease.22 Of note, all these four factors were more common among female compared to male SLE cases and could thus to some extent explain the gender difference of SDI.

Since the 1950s survival rates have improved, but during the last decades mortality rates have stagnated and unfortunately remain higher than in the general population.6,10 In our cohort, 10% were deceased at the data extraction time point. Malignancy was the leading cause of death, followed by infections and cardiovascular disease. This is partly in line with previous reports, of which some have shown higher rates for ‘active disease’, thrombotic events and cerebrovascular disease.14,33,45,46 A plausible explanation for this is an underestimation of the SLE-related causes of death in Sweden, which was recently highlighted by Falasinnu et al.47 Among the malignancies, lung and haematological cancers (including malignant lymphomas) were the most common, each constituting almost one third of the malignancy-related deaths in our cohort. Similar observations were made both in a large international SLE cohort study in which hepatobiliary cancer was also found to be overrepresented, as well as in a recent meta-analysis.45,48 Infection, which was the second most common cause of death, has been identified as a frequent cause of death in early SLE and can be linked to high disease activity, high doses of corticosteroids, immunosuppressive therapy and hospitalization.46,49 Early cardiovascular disease has frequently been reported as being overrepresented in SLE, especially in women, and remains a prevailing cause of death, also corroborated in this study.14,50

The large size and well-characterized population as well as the patients' universal access to healthcare constitute strengths of the present study. This, together with our university hospitals being tertiary referral centres, resulted in a high coverage of cases and a subsequent low risk of selection bias. The low number of non-Caucasians and the lack of data on accumulated corticosteroid doses are limitations that may hinder generalization to other parts of the world.

To conclude, despite Swedish healthcare being tax-funded and offering universal access, the majority of patients are still affected by irreversible organ damage over time. We confirmed previously established associations between variables and damage accrual in this study. In addition, SS was associated with (extensive) damage, whereas pericarditis, haemolytic anaemia, lymphopenia and myositis were linked to global SDI in a multiple regression model. Among the modifiable factors, a judicious use of corticosteroids seems to be very important as well as surveillance and prevention of cardiovascular disease and vigilance for malignancies to prevent damage and premature mortality.

Supplementary Material

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Rheumatism Association, the County Council of Östergötland and Uppsala, the Swedish Society of Medicine and Ingegerd Johansson donation, the Selander foundation, the King Gustaf V's 80-year Anniversary foundation and the King Gustaf V and Queen Victoria's Freemasons foundation.

References

- 1.Bruce IN, O'Keeffe AG, Farewell V, Hanly JG, Manzi S, Su L, et al. Factors associated with damage accrual in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: results from the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) Inception Cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74: 1706–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bengtsson AA, Ronnblom L. Systemic lupus erythematosus: still a challenge for physicians. J Intern Med 2017; 281: 52–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahman P, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Hallett D, Tam LS. Early damage as measured by the SLICC/ACR damage index is a predictor of mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2001; 10: 93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mak A, Cheung MW, Chiew HJ, Liu Y, Ho RC. Global trend of survival and damage of systemic lupus erythematosus: meta-analysis and meta-regression of observational studies from the 1950s to 2000s. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2012; 41: 830–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urowitz MB, Gladman DD, Tom BD, Ibanez D, Farewell VT. Changing patterns in mortality and disease outcomes for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2008; 35: 2152–2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tektonidou MG, Lewandowski LB, Hu J, Dasgupta A, Ward MM. Survival in adults and children with systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review and Bayesian meta-analysis of studies from 1950 to 2016. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76: 2009–2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, Sebastiani GD, Gil A, Lavilla P, et al. Morbidity and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus during a 5-year period. A multicenter prospective study of 1,000 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1999; 78: 167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee YH, Choi SJ, Ji JD, Song GG. Overall and cause-specific mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus: an updated meta-analysis. Lupus 2016; 25: 727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruiz-Irastorza G, Egurbide MV, Ugalde J, Aguirre C. High impact of antiphospholipid syndrome on irreversible organ damage and survival of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164: 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jorge AM, Lu N, Zhang Y, Rai SK, Choi HK. Unchanging premature mortality trends in systemic lupus erythematosus: a general population-based study (1999–2014). Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018; 57: 337–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stoll T, Seifert B, Isenberg DA. SLICC/ACR Damage Index is valid, and renal and pulmonary organ scores are predictors of severe outcome in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Rheumatol 1996; 35: 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gladman D, Ginzler E, Goldsmith C, Fortin P, Liang M, Urowitz M, et al. The development and initial validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology damage index for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1996; 39: 363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nived O, Jonsen A, Bengtsson AA, Bengtsson C, Sturfelt G. High predictive value of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology damage index for survival in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2002; 29: 1398–1400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chambers SA, Allen E, Rahman A, Isenberg D. Damage and mortality in a group of British patients with systemic lupus erythematosus followed up for over 10 years. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009; 48: 673–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjork M, Dahlstrom O, Wettero J, Sjowall C. Quality of life and acquired organ damage are intimately related to activity limitations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2015; 16: 188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sohn IW, Joo YB, Won S, Bae SC. Late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: Is it “mild lupus”?. Lupus 2018; 27: 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petri M, Purvey S, Fang H, Magder LS. Predictors of organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus: the Hopkins Lupus Cohort. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64: 4021–4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conti F, Ceccarelli F, Perricone C, Leccese I, Massaro L, Pacucci VA, et al. The chronic damage in systemic lupus erythematosus is driven by flares, glucocorticoids and antiphospholipid antibodies: results from a monocentric cohort. Lupus 2016; 25: 719–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutton EJ, Davidson JE, Bruce IN. The systemic lupus international collaborating clinics (SLICC) damage index: a systematic literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2013; 43: 352–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frodlund M, Vikerfors A, Grosso G, Skogh T, Wettero J, Elvin K, et al. Immunoglobulin A anti-phospholipid antibodies in Swedish cases of systemic lupus erythematosus: associations with disease phenotypes, vascular events and damage accrual. Clin Exp Immunol 2018; 194: 27–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ighe A, Dahlstrom O, Skogh T, Sjowall C. Application of the 2012 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria to patients in a regional Swedish systemic lupus erythematosus register. Arthritis Res Ther 2015; 17: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frodlund M, Dahlstrom O, Kastbom A, Skogh T, Sjowall C. Associations between antinuclear antibody staining patterns and clinical features of systemic lupus erythematosus: analysis of a regional Swedish register. BMJ Open 2013; 3: e003608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leonard D, Svenungsson E, Sandling JK, Berggren O, Jonsen A, Bengtsson C, et al. Coronary heart disease in systemic lupus erythematosus is associated with interferon regulatory factor-8 gene variants. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2013; 6: 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcon GS, Gordon C, Merrill JT, Fortin PR, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64: 2677–2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1982; 25: 1271–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goncalves MJ, Sousa S, Ines LS, Duarte C, Borges J, Silva C, et al. Characterization of damage in Portuguese lupus patients: analysis of a national lupus registry. Lupus 2015; 24: 256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chambers SA, Charman SC, Rahman A, Isenberg DA. Development of additional autoimmune diseases in a multiethnic cohort of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus with reference to damage and mortality. Ann Rheum Dis 2007; 66: 1173–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taraborelli M, Leuenberger L, Lazzaroni MG, Martinazzi N, Zhang W, Franceschini F, et al. The contribution of antiphospholipid antibodies to organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2016; 25: 1365–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis MJ, Jawad AS. The effect of ethnicity and genetic ancestry on the epidemiology, clinical features and outcome of systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 2017; 56: 67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danchenko N, Satia JA, Anthony MS. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of worldwide disease burden. Lupus 2006; 15: 308–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rees F, Doherty M, Grainge MJ, Lanyon P, Zhang W. The worldwide incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017; 56: 1945–1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gustafsson JT, Gunnarsson I, Kallberg H, Pettersson S, Zickert A, Vikerfors A, et al. Cigarette smoking, antiphospholipid antibodies and vascular events in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74: 1537–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lerang K, Gilboe IM, Steinar Thelle D, Gran JT. Mortality and years of potential life loss in systemic lupus erythematosus: a population-based cohort study. Lupus 2014; 23: 1546–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nossent JC, Swaak AJ. Systemic lupus erythematosus VII: frequency and impact of secondary Sjogren's syndrome. Lupus 1998; 7: 231–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baer AN, Maynard JW, Shaikh F, Magder LS, Petri M. Secondary Sjogren's syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus defines a distinct disease subset. J Rheumatol 2010; 37: 1143–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prasad R, Ibanez D, Gladman D, Urowitz M. Anti-dsDNA and anti-Sm antibodies do not predict damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2006; 15: 285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liang Y, Leng RX, Pan HF, Ye DQ. Associated variables of myositis in systemic lupus erythematosus: a cross-sectional study. Med Sci Monit 2017; 23: 2543–2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheema GS, Quismorio FP Jr. Interstitial lung disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2000; 6: 424–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levine AB, Erkan D. Clinical assessment and management of cytopenias in lupus patients. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2011; 13: 291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akhavan PS, Su J, Lou W, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Fortin PR. The early protective effect of hydroxychloroquine on the risk of cumulative damage in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2013; 40: 831–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wallace DJ. Antimalarial agents and lupus. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1994; 20: 243–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rahman P, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Yuen K, Hallett D, Bruce IN. The cholesterol lowering effect of antimalarial drugs is enhanced in patients with lupus taking corticosteroid drugs. J Rheumatol 1999; 26: 325–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lakshminarayanan S, Walsh S, Mohanraj M, Rothfield N. Factors associated with low bone mineral density in female patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2001; 28: 102–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan TC, Fang H, Magder LS, Petri MA. Differences between male and female systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic population. J Rheumatol 2012; 39: 759–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bernatsky S, Boivin JF, Joseph L, Manzi S, Ginzler E, Gladman DD, et al. Mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54: 2550–2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cervera R, Khamashta M, Hughes G. The Euro-lupus project: epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus in Europe. Lupus 2009; 18: 869–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Falasinnu T, Rossides M, Chaichian Y, Simard JF. Do death certificates underestimate the burden of rare diseases? The example of systemic lupus erythematosus mortality, Sweden, 2001–2013. Public Health Rep 2018; 133: 481–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Song N, Xu X, Lu Y. The risks of cancer development in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther 2018; 20: 270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hou C, Jin O, Zhang X. Clinical characteristics and risk factors of infections in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol 2018; 37: 2699–2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schoenfeld SR, Kasturi S, Costenbader KH. The epidemiology of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease among patients with SLE: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2013; 43: 77–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.