Abstract

Objective.

As anti-amyloid therapeutic interventions shift from enrolling patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia to individuals with pre-clinical disease, the need for sensitive measures that allow for non-invasive, fast, disseminable and cost-effective identification of preclinical status increases in importance. The recency ratio (Rr) is a memory measure that relies on analysis of serial position performance, which has been found to predict cognitive decline and conversion to early mild cognitive impairment (MCI). The aim of this study was to test Rr’s sensitivity to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of the core AD biomarkers in individuals with MCI-AD and controls.

Methods.

Baseline data from 126 (110 controls and 16 MCI-AD) participants from the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center were analysed. Partial correlations adjusting for demographics were carried out between CSF measure of amyloid beta (Aβ40, Aβ42 and the 40/42 ratio) and tau (total and phosphorylated), and memory measures (Rr, delayed recall and total recall) derived from the Rey’s Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

Results.

Results indicated that Rr was the most sensitive memory score to Aβ42 levels in MCI-AD, while no memory score correlated significantly with any biomarker in controls.

Conclusions.

This study shows that Rr is a sensitive cognitive index of underlying Amyloid β pathology in MCI-AD.

Keywords: A/T/N biomarkers, Amyloid β, Alzheimer’s disease, Recency ratio

Introduction

The recency ratio (Rr) [1–3] is a novel measure of memory performance that aims to identify individuals at risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and neurodegeneration. Sensitivity of Rr is based on the observations that individuals with AD, compared to controls, when asked to learn and recall information, present a typical pattern whereby: a) immediate recall of the most recently presented information (i.e., recency words – last few learned) is higher relative to earlier presented information, and to controls; whereas b) the delayed recall of recency words is usually very poor [4]. Therefore, we postulated that the ratio between immediate and delayed recency would be higher in individuals with more AD pathology. Consistent with this assertion, we have shown that higher (i.e., worse) Rr scores predict subsequent cognitive decline [1], and are linked with greater risk of preclinical (early) mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [3]. Moreover, initial, unpublished evidence suggests Rr scores are substantially higher in AD than in other types of dementia, such as dementia with Lewy bodies [5]. However, the relationship between Rr and AD biomarkers is yet to be examined.

In the current study, we set out to test the hypothesis that Rr is sensitive to conventional biomarkers of AD by assessing the relationship between Rr and CSF levels of Amyloid Beta 1–42 (Aβ42), total tau (T-tau), and phosphorylated tau (P-tau), in addition to Amyloid Beta 1–40 (Aβ40), and the Aβ40/Aβ42 ratio. The first three biomarkers provide the basis for the objective, biomarker-based (A/T/N; 6) classification of AD cases. Disturbances in Aβ42 dynamics emerge early in the pathophysiology of AD and decades before the appearance of pathological cognitive decline [7]. Aβ42 plays a central role in the formation of senile plaques resulting from the peptide’s misfolding to form oligomers and fibrils. In contrast, alterations in T-tau and P-tau have been reported to be more proximal to clinical symptoms, and generally thought to reflect later neuropathology associated with AD [8], including increases in neurofibrillary tangles formation, and synaptic and neuronal degeneration. Unlike with tau, CSF Aβ42 levels are reduced when the amyloid burden is higher in the brain [9], probably due to reduced clearance. Therefore, we would expect a cognitive marker sensitive to early AD pathology would be associated with lower CSF Aβ42 levels, indicating increased amyloid load in the brain. In contrast, a cognitive marker sensitive to progressed disease burden would measure neuronal dysfunction and tau dysmetabolism that may relate to neurodegeneration and tangle formation, i.e., CSF T-tau and P-tau levels. We also examined whether Rr showed a stronger relationship with CSF markers than either traditional AVLT summary score (total recall across learning trials and delayed recall).

To test whether Rr was sensitive to AD biomarkers, we carried out cross-sectional analyses using data obtained from the University of Wisconsin – Madison’s Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC). As individuals with MCI-AD and cognitively healthy controls are distinct clinical entities, we conducted separate analyses within each group. Individuals with MCI-AD are at greater risk of AD than controls, but conversion to dementia is not inevitable. Discerning those likely to convert from those whose impairment is stable would allow for targeted and cost-effective interventions. Presently, methods to assess likelihood of conversion are invasive and resource intense, e.g., CSF collection from lumbar puncture or PET imaging of amyloid and tau. It is critical, therefore, to develop measures that allow a non-invasive, disseminable, and cost-effective identification of who is most likely to progress to the dementia stage of AD, especially in at-risk cohorts.

Methods

Participants.

Participants were recruited from Wisconsin ADRC. All participants provided informed consent for participation and use of their data for research. The study was approved by the University of Wisconsin – Madison IRB, and by Liverpool John Moores University Ethics panel. Data were analysed cross-sectionally (baseline) from 126 participants fulfilling the following criteria: a) diagnosis of MCI-AD or classification as cognitively normal; b) complete Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test data; and c) available CSF Aβ40, Aβ42, T-tau and P-tau levels collected within 12 months of cognitive data. The cognitive status (MCI-AD, cognitively healthy) was determined via a consensus conference, during which cognitive data, Clinical Dementia Rating collateral reports, and medical history were reviewed by a team of neuropsychologists, neurologists, geriatricians and nurse practitioners. MCI-AD here refers to participant characteristics consistent with National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) criteria of early cognitive deficits on path to AD, without reaching the threshold for a full diagnosis of dementia [10]. Overall, 110 individuals were controls, and 16 participants had MCI-AD.

Aβ and Tau.

CSF Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels were measured using the MSD Abeta Triplex assay (Meso Scale Discovery, Rockville, MD), as described by the manufacturer. Tau levels were analyzed using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) methods (INNOTEST assays, Fujirebio, Ghent, Belgium). All analyses were performed by board-certified laboratory technicians blinded to clinical information.

Procedure.

Lumbar punctures for CSF collection were performed by trained clinicians using Sprotte 25-gauge spinal needles, inserted between L4 and L5, after administration of 1% lidocaine s.c.. Polypropylene tubes were used for both collection and storage. Approximately 22ml of CSF were collected, immediately processed, divided into 0.5 ml aliquots and stored at −80°C for future assays. Samples were then shipped to the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, for determination. Average time between CSF collection and neuropsychological assessment was 0.19 years (SD=0.18) for controls, and 0.20 years (SD=0.13) for individuals with MCI-AD.

The Rey’s Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) was used to assess learning and memory performance. In the AVLT, a list of 15 semantically unrelated words is presented verbally to the participants once, after which they are asked to free recall as many words as possible. Subsequently, this presentation-test routine (learning trials) is repeated four more times. A total recall score is determined by adding the number of recalled items for the five learning trials. After presentation of a distractor list and a delay of approximately 20 minutes, participants are asked to freely recall items from the original word list. A delayed recall score is then derived from this test. The verbatim recall was recorded for all learning and delayed recall trials.

Recency ratio.

Recency was defined as the last four items presented in the AVLT word list. Rr was calculated by dividing the recency scores in the first recall test (trial 1 of the AVLT), by the corresponding scores in the very last recall test (delayed trial). An Rr score was calculated for each participant. As customary [3], a correction was applied ((immediate recency score + 1) / (delayed recency score + 1)) to avoid missing data due to zero scores.

Design and Analysis.

Partial Bivariate Pearson’s correlations, controlling for age, years of education and gender, were carried out separately for the controls and individuals with MCI-AD. Correlated variables were (natural log) transformed Rr, the AVLT total recall score, the AVLT delayed recall score, and (natural log) transformed Aβ40, Aβ42, the 40/42 ratio, T- and P-tau, all of which distributed normally or close to it. Bootstrapping (1000 samples) was also performed, and false discovery rate (FDR; 11) p-values were calculated for each set of analyses (controls and MCI-AD) separately to control for multiple tests.

Results

Table 1 reports demographics data for the study participants. Participants with MCI-AD were generally older and performed more poorly at memory tests. CSF Aβ42 levels and ratio scores were lower and higher, respectively, in individuals with MCI-AD, suggesting increased brain amyloid load. However, although T-tau was higher in individuals with MCI-AD, P-tau was not, despite high correlations between T- and P-tau in both participants groups (R≥0.890).

Table 1.

Demographics. N = number of participants included in the analysis who were either cognitively normal or had a diagnosis of MCI-AD; Age in years (mean, standard deviation, and range); Gender (number of females and percentage); Education in years (mean, standard deviation, and range); Aβ40, Aβ42, Aβ40/42 ratio, total tau (T-tau) and hyperphosphorylated tau (P-tau) (means and standard deviations in pg/mL); AVLT total recall score (mean and standard deviation); AVLT delayed recall score (mean and standard deviation); and Rr score (mean and standard deviation). The last column reports p values for t-tests or Fisher’s exact test (Females).

| Cognitively Normal | MCI-AD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 110 (87%) | 16 (13%) | Significance |

| Age at baseline | 62.5 (9.2; 45–85) | 72.7 (7.1; 60–83) | p<0.001 |

| Females | 79 (72%) | 4 (25%) | p<0.001 |

| Years of education | 16.1 (2.5 ; 8–21) | 16.2 (2.9 ; 12–20) | p=0.847 |

| CSF Aβ40 | 10243.8 (3367.7) | 8843.9 (2662.9) | p=0.112a |

| CSF Aβ42 | 1052.5 (393.5) | 683.0 (218.1) | p<0.001a |

| 40/42 ratio | 10.3 (2.9) | 14.2 (5.4) | p<0.001a |

| CSF T-tau | 326.9 (178.4) | 471.4 (263.6) | p=0.007a |

| CSF P-tau | 43.6 (16.8) | 51.9 (28.1) | p=0.186a |

| AVLT total recall | 48.5 (8.8) | 32.8 (5.5) | p<0.001 |

| AVLT del. recall | 2.2 (1.2) | 0.6 (0.6) | p<0.001 |

| Rr | 1.2 (0.7) | 2.3 (0.9) | p<0.001a |

The analyses were carried out using natural log-transformed scores

MCI-AD group.

As anticipated, Rr was negatively correlated with CSF Aβ42 in individuals with MCI after partialling out age, education and sex, (R=−0.762, p=0.002; bootstrapped 95% confidence interval −0.952 to −0.198). This result suggests that higher Rr scores were associated with increased brain amyloid load. In contrast, neither total (p=0.357) nor delayed recall (p=0.107) were significantly correlated with CSF Aβ42 levels. None of the three memory scores appeared to be sensitive to CSF Aβ40 levels (p > 0.490 for all three tests), or T- and P-tau levels (p > .15 for all six tests). Rr was significantly correlated with the 40/42 ratio score (R=0.624, p=0.023), but bootstrapped 95% confidence interval were not of the same sign: −0.021 to 0.906. See Table 2 for partial correlation coefficients, p-values, FDR-adjusted p-values, and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals.

Table 2.

Partial correlation coefficients, p-values, FDR-adjusted p-values, and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals for analyses, divided by controls and MCI-AD. Significant correlations are reported in bold. If still significant after FDR-adjustment, also italicized.

| Coefficient | −0.020 | 0.058 | 0.000 | 0.024 | ||

| p-value | 0.841 | 0.551 | 1.000 | 0.803 | ||

| 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||

| Lower | −0.211 | −0.171 | −0.179 | −0.165 | ||

| Upper | 0.186 | 0.276 | 0.167 | 0.195 | ||

| Coefficient | −0.007 | −0.032 | −0.086 | −0.096 | ||

| p-value | 0.946 | 0.741 | 0.380 | 0.323 | ||

| 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||

| Lower | −0.200 | −0.243 | −0.261 | −0.267 | ||

| Upper | 0.190 | 0.171 | 0.085 | 0.088 | ||

| Coefficient | 0.057 | 0.012 | 0.100 | 0.135 | ||

| p-value | 0.557 | 0.902 | 0.305 | 0.164 | ||

| 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||

| Lower | −0.131 | −0.166 | −0.090 | −0.085 | ||

| Upper | 0.246 | 0.187 | 0.276 | 0.334 | ||

| Coefficient | 0.279 | −0.276 | −0.232 | −0.398 | ||

| p-value | 0.357 | 0.361 | 0.445 | 0.178 | ||

| 0.548 | 0.548 | 0.556 | 0.445 | |||

| Lower | −0.486 | −0.811 | −0.778 | −0.845 | ||

| Upper | 0.8 | 0.35 | 0.446 | 0.265 | ||

| Coefficient | 0.467 | −0.405 | −0.309 | −0.403 | ||

| p-value | 0.107 | 0.170 | 0.305 | 0.172 | ||

| 0.445 | 0.445 | 0.548 | 0.445 | |||

| Lower | −0.32 | −0.926 | −0.873 | −0.884 | ||

| Upper | 0.863 | 0.347 | 0.417 | 0.271 | ||

| Coefficient | −0.762 | 0.624 | 0.274 | 0.239 | ||

| p-value | 0.002 | 0.023 | 0.365 | 0.431 | ||

| 0.030 | 0.173 | 0.548 | 0.557 | |||

| Lower | −0.952 | −0.021 | −0.386 | −0.361 | ||

| Upper | −0.198 | 0.906 | 0.744 | 0.735 | ||

Cognitively intact group.

In cognitively unimpaired controls, correlation coefficients were much smaller than in the MCI-AD group, and none of the relationships between memory and CSF measures were significant after adjusting for age, education and sex (p>16; see Table 2).

Rr and adjusted CSF Aβ42 in both groups.

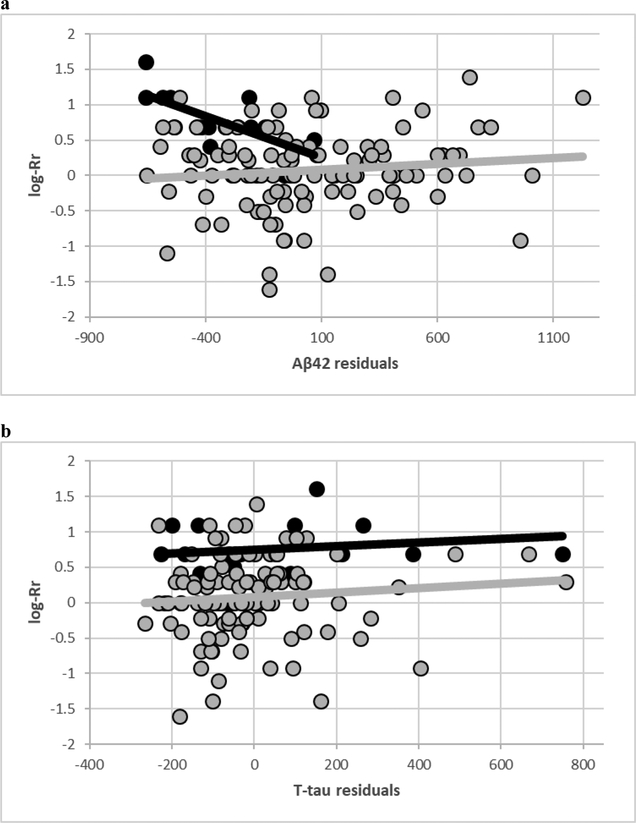

Figure depicts the correlations between CSF Aβ42 (adjusted for age, education and sex) and log-transformed Rr in MCI-AD and controls. Notably, MCI-AD subjects tend to cluster around higher Rr scores and lower CSF Aβ42 levels, respectively, consistent with the differences reported in Table. We also report the same plot with T-tau for comparison.

Figure.

a) Plot of CSF Aβ42 unstandardized residuals (age, education and sex; X-axis) by log-transformed Rr (Y-axis). Black represents individuals with MCI-AD, and grey represents healthy controls.

b) Plot of CSF T-tau unstandardized residuals (age, education and sex; X-axis) by log-transformed Rr (Y-axis). Black represents individuals with MCI-AD, and grey represents healthy controls.

Discussion

The results of the cross-sectional analysis on baseline data, collected from participants enrolled in the Wisconsin ADRC Clinical Core, show that Rr is a sensitive measure of CSF Aβ42 levels in individuals with MCI-AD, performing significantly better than standard neuropsychological measures of memory, such as AVLT total and delayed recall. In contrast, no memory score was sensitive to CSF Aβ42 levels in controls, nor any score correlated significantly with Aβ40, the 40/42 ratio, T- or P-Tau levels in either cohort.

The basis for the association between Rr and CSF Aβ42 is not known. Increased amyloid burden in AD tends to develop first in default mode network (DMN) areas, leading to reduced connectivity within these areas, and between the DMN and the frontoparietal network [12]. In contrast, early tau pathology has been detected primarily in the medial temporal lobe [13]. Therefore, it is possible that Rr may be sensitive to the adverse effects of early brain amyloid deposition, and specifically as it affects connectivity in and around the DMN. It is also to note that increases in Amyloid β oligomers and deposition in the neocortex have been associated with a disruption of the glutamatergic-gabaergic balance, and widespread abnormal increases in neuronal activity, which can extend to the hippocampus [14–16]. Hippocampal neuronal hyperactivity has been reported in MCI, and is implicated in cognitive dysfunction [17; see also 18 for a wider discussion on hyperactivity]. Therefore, future studies with appropriate neuroimaging techniques including PET indices of Amyloid burden and fMRI should be conducted to determine the role, if any, that these factors may have in the modulation of Rr.

A clear limitation of this study is the low sample size in the MCI-AD group, which totalled at 16 individuals. Additionally, brain AD biomarkers were not examined. Nonetheless, further research is needed to confirm these findings. Another possible limitation is that the time interval between CSF and cognitive measurements was roughly two months. While cognitive ability is not expected to change significantly during such a short time period, as cognitive change, even in MCI-AD, is expected to be rather slow, CSF biomarkers may turn over faster than two months. However, there is typically more concern about diurnal shifts in CSF proteins than month to month changes (19), and it is generally accepted that changes in CSF biomarkers levels reflecting brain changes will also progress slowly. Therefore, two months should represent a broadly acceptable interval length.

Rr represents a non-invasive, cost-effective, rapid and accessible test, which can be easily calculated from common neuropsychological test batteries of recall performance, including the AVLT, as long as learning items are not semantically related. Due to its sensitivity to CSF Aβ42 levels in MCI-AD, as well as its usefulness to predict pre-clinical MCI (3) and CSF glutamatergic abnormalities (2), we recommend that it is considered as part of screening batteries for early-stage therapeutic trials in AD. Moreover, as we have argued in the past, we recommend that serial position data for recall tests are included in databases for the study of AD and neurodegeneration.

Key points:

This paper confirms that the recency ratio is a valuable cognitive index, and shows its sensitivity to CSF levels of Aβ42 in MCI-AD.

Acknowledgments

The authors report no conflicts of interests. This research was funded by the Swedish Alzheimer Foundation (Grant #AF-742881), the Torsten Söderberg Foundation at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Research Council, Sweden (Project #2017–00915), and Hjärnfonden, Sweden (project # FO2017–0243). This research was also supported by funding from the NIA-NIH (P50 AG033514; R01 AG054059), as well as the Madison VA GRECC. This is GRECC Manuscript number 006–2018.

References

- 1.Bruno D, Reichert C, Pomara N. The recency ratio as an index of cognitive performance and decline in elderly individuals. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2016; 38:967–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruno D, Nierenberg J, Cooper TB, Marmar CR, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Hashimoto K, Pomara N. The recency ratio is associated with reduced CSF glutamate in late-life depression. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2017. May 1;141:14–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruno D, Koscik RL, Woodard JL, Pomara N, Johnson SC. The recency ratio as predictor of early MCI. International psychogeriatrics. 2018. April:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlesimo GA, Sabbadini M, Fadda L, Caltagirone C. Different components in word-list forgetting of pure amnesics, degenerative demented and healthy subjects. Cortex. 1995. December 1;31(4):735–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruno D, Busse’ C, Cagnin A. Effective discrimination between Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies with the recency ratio Conference paper, Meeting of the International Neuropsychology Society, Prague, Czech Republic, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Feldman HH, Frisoni GB, Hampel H, Jagust WJ, Johnson KA, Knopman DS, Petersen RC. A/T/N: An unbiased descriptive classification scheme for Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Neurology 2016; 87:539–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Goate A, Fox NC, Marcus DS, Cairns NJ, Xie X, Blazey TM, Holtzman DM. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012. August 30;367(9):795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Musiek ES, Holtzman DM. Three dimensions of the amyloid hypothesis: time, space and’wingmen’. Nature neuroscience. 2015. June;18(6):800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blennow K, Hampel H, Weiner M, Zetterberg H. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma biomarkers in Alzheimer disease. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2010. March;6(3):131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Snyder PJ. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2011. May 1;7(3):270–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the royal statistical society. Series B (Methodological). 1995. January 1:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmqvist S, Schöll M, Strandberg O, Mattsson N, Stomrud E, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Landau S, Jagust W, Hansson O. Earliest accumulation of β-amyloid occurs within the default-mode network and concurrently affects brain connectivity. Nature Communications. 2017. October 31;8(1):1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho H, Choi JY, Hwang MS, Lee JH, Kim YJ, Lee HM, Lyoo CH, Ryu YH, Lee MS. Tau PET in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2016. July 26;87(4):375–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Busche MA, Konnerth A. Impairments of neural circuit function in Alzheimer’s disease. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2016. August 5;371(1700):20150429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Busche MA, Chen X, Henning HA, Reichwald J, Staufenbiel M, Sakmann B, Konnerth A. Critical role of soluble amyloid-β for early hippocampal hyperactivity in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012. May 29;109(22):8740–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lei M, Xu H, Li Z, Wang Z, O’Malley TT, Zhang D, Walsh DM, Xu P, Selkoe DJ, Li S. Soluble Aβ oligomers impair hippocampal LTP by disrupting glutamatergic/GABAergic balance. Neurobiology of disease. 2016. January 1;85:111–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bakker A, Krauss GL, Albert MS, Speck CL, Jones LR, Stark CE, Yassa MA, Bassett SS, Shelton AL, Gallagher M. Reduction of hippocampal hyperactivity improves cognition in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuron. 2012. May 10;74(3):467–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pomara N, Bruno D. Pathological Increases in Neuronal Hyperactivity in Selective Cholinergic and Noradrenergic Pathways May Limit the Efficacy of Amyloid-β-Based Interventions in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease Reports. 2018. (Preprint):1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bateman RJ, Wen G, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. Fluctuations of CSF amyloid-β levels: implications for a diagnostic and therapeutic biomarker. Neurology. 2007;68:666–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]