Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent cells able to differentiate into multiple cell types, including adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes. The role of adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) in cancers is significantly relevant. They seem to be involved in the promotion of tumour development and progression and relapse processes. For this reason, investigating the effects of breast cancer microenvironment on ADSCs is of high importance in order to understand the relationship between tumour cells and the surrounding stromal cells. With the current study, we aimed to investigate the specific characteristics of human ADSCs isolated from the adipose tissue of breast tumour patients. We compared ADSCs obtained from periumbilical fat (PF) of controls with ADSCs obtained from adipose tissue of breast cancer- (BC-) bearing patients. We analysed the surface antigens and the adipogenic differentiation ability of both ADSC populations. C/EBPδ expression was increased in PF and BC ADSCs induced to differentiate compared to the control while PPARγ and FABP4 expressions were enhanced only in PF ADSCs. Conversely, adiponectin expression was reduced in PF-differentiated ADSCs while it was slightly increased in differentiated BC ADSCs. By means of Oil Red O staining, we further observed an impaired differentiation capability of BC ADSCs. To investigate this aspect more in depth, we evaluated the effect of selective PPARγ activation and nutritional supplementation on the differentiation efficiency of BC ADSCs, noting that it was only with a strong differentiation stimuli that the process took place. Furthermore, we observed no response in BC ADSCs to the PPARγ inhibitor T0070907, showing an impaired activation of this receptor in adipose cells surrounding the breast cancer microenvironment. In conclusion, our study shows an impaired adipogenic differentiation capability in BC ADSCs. This suggests that the tumour microenvironment plays a key role in the modulation of the adipose microenvironment located in the surrounding tissue.

1. Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are used in regenerative medicine for the treatment of tissue damage after specific pathological processes, such as graft versus host disease, articular cartilage, and other bone injuries [1]. MSCs can be efficiently derived from different tissues such as the bone marrow, the adipose tissue, the skin, and the muscle [2]. They are multipotent cells with the ability to differentiate into various cell types, such as adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes [3]. The adipose tissue is an important endocrine and metabolic organ characterized by different functions, ranging from hormone secretion to heat production. It contains different cell types such as stromal vascular cells, which include adipose stem cells (ADSCs), and endothelial progenitor cells [4]. ADSCs have proangiogenic, antiapoptotic, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory effects, through paracrine secretion of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors [5, 6]. These functions make them optimal candidates for cellular therapy in regenerative medicine [7]. Even so, ADSCs are also involved in promoting tumour development and progression, as well as relapse processes in different cancer types [8]. Recent studies focused on the interaction between the stromal resident cells, such as ADSCs, cancer-associated fibroblasts, and cells deriving from primary tumour [9]. Several evidences indicate that the cellular functions associated with invasion and metastasis are not produced by carcinoma cells, but they are a transient response to signals that tumour cells receive from their stromal microenvironment [10, 11]. Indeed, human breast cancer cells mixed with bone marrow-derived human MSCs, injected subcutaneously, in a mouse model recruit murine MSCs and the further circulating human cancer cells, also stimulating the de novo secretion of the chemokine CCL5. This suggests that invasion and metastasis of cancer cells from the primary site are driven by signals released from the stroma of the primary tumour [10]. Indeed, the interaction of human breast carcinoma cells with bone marrow-derived human MSCs significantly increases metastatic potency. Moreover, the interaction of cancer cells and MSCs induces the transformation of MSCs into cancer-associated fibroblasts through the production of CCL5 and osteopontin, promoting tumour progression [12].

For these reasons, investigating the effects of breast cancer (BC) microenvironment on ADSCs could be of crucial importance in order to understand the interaction between the tumour and its microenvironment. Indeed, it is known that stromal cells located near the BC microenvironment may develop into mammary carcinogenesis [13]. Interestingly, even if the adipose tissue is the most abundant stromal constituent in the breast, little is known about the involvement of resident ADSCs in the BC development. BC is a frequent carcinoma in postmenopausal women [14] and is classified in different groups based on the gene expression profile: luminal A, luminal B, HER2, and basal-like breast cancer (BLBC) [15]. Increased adiposity and obesity are associated with an elevated risk of the onset of the most prevalent form of BC [16]. Clinical experiences have sustained that BC often develops in close association with fat [9]; moreover, age is a risk factor, since during the aging process the mammary tissue becomes richer in fat and less dense [17]. Adipose tissue can be easily isolated in abundant quantities from many sites, such as the abdomen and breast [18]. The adipogenic process conducted by ADSCs is subsequent to the activation of PPARγ, the receptor responsible for the induction of this process [19]. PPARγ's expression has been reported to be deregulated in breast cancer patients, along with other cancer types [20, 21]. Furthermore, multiple studies are investigating the therapeutic potential of PPARγ modulators as innovative cancer therapy [22, 23]. The role that nutrition and especially low- versus high-fat diets play in breast cancer outcomes becomes even more highlighted [24–28]. Indeed, studies demonstrated that a low-fat diet is associated with a significant improvement in overall survival [24]. Multiple protocols use lipid mixtures in in vitro cultures to mimic a high-fat diet and investigate cellular responses [29]. Moreover, in murine experimental models, it has been demonstrated that obesity is associated with increased survival and persistence of residual tumour cells [26]. Furthermore, dietary fat could modulate the homeostasis of the adipose tissue acting on processes such as autophagy and apoptosis [30].

The aim of our study was to investigate whether ADSCs isolated from the adipose tissue of BC-bearing patients have specific cellular and functional characteristics that may be influenced, in a bidirectional manner, by the BC microenvironment and by the tumour itself. Indeed, there could be differences in qualitative and quantitative characteristics of these ADSC populations, in terms of their adaptation to extended culture and multipotency, or their response to specific stimuli, which ultimately relates to practical considerations regarding also their possible clinical use.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Tissues were isolated within the Surgery Unit of San Paolo Hospital. Patients gave their informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Milan of San Paolo Hospital (n. 11698; July 06, 2016). The study participants were 20 female patients with breast cancer (BC; Table 1) and 8 women who underwent surgery for the removal of umbilical hernia or epigastric hernia (CTRL; periumbilical fat (PF)). All patients enrolled in this study had a normal BMI (18.5 ≤ BMI ≤ 24.9). In BC patients, a sample of breast fat was taken 5 cm away from the cancer lesion. Control fat samples were collected from the subcutaneous tissue of the abdomen of patients affected with elective benign, noninflammatory, and noninfectious diseases, namely, umbilical and epigastric hernias. Control subjects and BC carriers belonged to the same age group (median 62.3 controls and 63.5 years BC). Subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue is rich in stem cells and is commonly used for breast lipofilling for its affinity to breast fat.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the 20 breast cancer-affected patients enrolled in the present study.

| N | Age | Histology | Grading | ER | PR | Ki67 (%) | Her2/neu | TNM | Stage | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 56 | LIC | G2 | + | + | 10 | - | pT1b, N0(sn) | IA | QDR+SNB |

| 2 | 69 | DIC | G2 | + | + | 25 | - | pT1b, Nx | IA | QDR |

| 3 | 75 | DIC | G2 | + | - | 8 | + | pT1c, N1mi(sn) | IB | QDR+SNB |

| 4 | 82 | DIC | G3 | + | - | 35 | + | pT2, pN1a | IIB | QDR+AND |

| 5 | 54 | DIC | G3 | + | - | 25 | + | pT1c, pN0(sn) | IA | QDR+SNB |

| 6 | 48 | DIC | G2 | + | + | 40 | + | pT2, N1a | IIB | QDR+AND |

| 7 | 63 | DIC | G3 | + | + | 25 | + | pT1c, N0(sn) | IA | QDR+SNB |

| 8 | 66 | DIC | G2 | + | + | 10 | - | pT1b, N0(sn) | IA | QDR+SNB |

| 9 | 64 | DIC | G2 | + | + | 8 | + | pT1c, pN0(sn) | IA | QDR+SNB |

| 10 | 78 | DIC | G2 | + | + | 12 | + | pT1c, pN0(sn) | IA | QDR+SNB |

| 11 | 47 | DIC∗ | G2 | + | + | 8 | + | pT1c, pN1mi | IB | QDR+SNB |

| 12 | 69 | DIC | G2 | + | + | 15 | - | pT1c, pN0(sn) | IA | QDR+SNB |

| 13 | 44 | DIC | G1 | + | + | 12 | + | pT1c, pN1mi | IB | QDR+SNB |

| 14 | 52 | DIC | G3 | - | - | 85 | - | pT1c, pN1a | IIA | QDR+AND |

| 15 | 66 | DIC | G2 | + | + | 18 | + | pT2, pN0(sn) | IIA | QDR+SNB |

| 16 | 58 | LIC | G2 | + | + | 10 | - | pT2, pN3a | IIIC | QDR+AND |

| 17 | 68 | DIC | G1 | + | + | 5 | + | pT1b, pN0(sn) | IA | QDR+SNB |

| 18 | 76 | DIC | G3 | + | + | 55 | + | pT2, pN1a(sn) | IIB | QDR+AND |

| 19 | 65 | DIC | G2 | + | + | 12 | + | pT1b, pN0(sn) | IA | QDR+SNB |

| 20 | 63 | LIC | G2 | + | + | 10 | + | pT2, pN1mi(sn) | IIB | QDR+SNB |

ER: estrogen receptors; PR: progesterone receptors; TNM: according to AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer)/UICC (Union for International Cancer Control) classification: release 2017; LIC: lobular infiltrating carcinoma; DIC: ductal infiltrating carcinoma; DIC∗: ductal infiltrating carcinoma, papillary variant; QDR: standard quadrantectomy; SNB: sentinel node biopsy; AND: axillary node dissection; sn: sentinel node; mi: node micrometastasis.

2.2. Primary Cell Culture

Primary cell cultures, obtained from PF and from mammary fat of patients with BC, were cultured following previously published protocols [31]. The cells were cultured in Minimum Essential Media α medium (MEMα; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 15% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS; JRH Bioscience, Lenexa, KS, USA) and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. After 15 days, the medium and the tissues were removed and adherent cells were maintained in culture. The medium was changed every 3 days until the cells reached confluence (85%). To avoid spontaneous differentiation, cells were maintained at a subconfluent culture level. When the cells reached 85% confluence, they were detached with 0.05% trypsin/EDTA solution (Thermo Fisher), collected by centrifugation (1200 rpm × 5 min) and expanded in culture or cryopreserved at −80°C in the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; 10%, FBS 90%). All in vitro experiments were performed in 5 isolates of each group (PF ADSCs and BC ADSCs) with similar results. All reported images are representatives of what was observed in the 5 isolates. Immunofluorescence and Oil Red O quantifications were determined as the mean of 3 fields/isolate for 5 isolates.

2.3. Proliferation

Cellular proliferation was analysed by cumulative population doubling (CPD). Cells were plated at a density of 7000 cells/cm2 and counted by using trypan blue (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) at 85% confluence. Curves were obtained calculating the population doubling (PD) with the following:

| (1) |

where NS is the cell number at seeding (7000 cells/cm2) and NH is the cell number at harvest. To calculate the CPD, the PD determined for each passage is then added to the CPD of the previous passage. Cells were incubated for 5 min with 0.1% trypan blue (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), examined by light microscopy with a minimum of 100 total cells counted per slide, and scored as able (live) or unable to exclude the dye (apoptotic).

2.4. Immunophenotypic Characterization

Cultures of PF ADSCs and BC ADSCs at different passages (lower than passage 4) were phenotypically characterized following reference guidelines [32, 33]. ADSCs obtained from PF- or BC-bearing patients were detached with 0.05% trypsin/EDTA (Thermo Fisher), washed with PBS, and 100000 cells were resuspended in 250 μL of PBS without Ca2+ and Mg+ (Euroclone, Pero, Italy) and incubated with antibodies directed against specific surface markers. Cells were incubated on ice for 30 minutes with antibodies anti-CD44 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), anti-CD90 (Millipore, Massachusetts, USA), anti-CD34 (Miltenyi Biotec, Calderara di Reno, BO, Italy), anti-CD45 (BD Biosciences), anti-CD146 (Biocytex, USA), anti-CD31 (Miltenyi Biotec), anti-CD56 (Miltenyi Biotec), anti-CD105 (Serotec, Bio-Rad, Segrate, MI, Italy), anti-CD144 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), anti-CD166 (BD Biosciences), anti-CD133/2 (Miltenyi Biotec), anti-CD73 (BD Biosciences), and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor 2 (VEGFR2; R&D Systems). Cells were pelleted, washed, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 minutes. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis was performed on a FACSVerse flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), equipped with the Cell Sweet software for data analysis.

2.5. Immunofluorescence Staining

After seeding and differentiation (3500 cells/cm2) onto glass slides, cells were grown until 85% confluence. They were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich). After saturation and permeabilization (4% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.3% Triton X-100 (VWR International, Radnor, PA, USA)), cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against PPARγ (1 : 100; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), C/EBPβ (1 : 100; Cell Signaling Technology), C/EBPδ (1 : 100 Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA), FABP4 (1 : 100 Cell Signaling Technology), leptin R (1 : 100; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and adiponectin (1 : 100 Abcam). Cells were rinsed and then probed for 45 minutes with secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (2 μg/mL in PBS; Sigma-Aldrich), and glasses were mounted with FluorSave™ (Millipore). Images were taken using a Leica SP2 confocal microscope with He/Kr and Ar lasers (Heidelberg, Germany). In negative control experiments, primary antibodies were replaced with equivalent concentrations of unrelated IgG of the same subclass. The quantification of positive cells was performed by considering a minimum of nine independent fields (three fields/three coverslips/treatment) captured with a 20x objective. The number of positive cells was expressed as the percentage to the total cell number given by DAPI nuclear staining.

2.6. Adipogenic Differentiation and Oil Red O Staining

PF and BC ADSCs were seeded (6000 cells/cm2) in adipogenic medium consisting of DMEM high glucose (Euroclone, MI, Italy) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 μmol/L dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methyl-xanthine (Sigma-Aldrich), and 10 μM insulin (Sigma-Aldrich) [34, 35]. Alternatively, BC ADSCs were also differentiated with standard adipogenic medium supplemented with 1 μg/mL troglitazone (Sigma-Aldrich), a potent PPARγ activator [36, 37], or with a 10% lipid mixture (Sigma-Aldrich) in order to mimic a high-fat diet [29]. The final lipidic concentration in this last reagent was thus 200 ng/mL arachidonic acid; 1 μg/mL linoleic, linolenic, myristic, oleic, palmitic, and stearic acids; 22 μg/mL cholesterol; and 7 μg/mL tocopherol acetate. The differentiation potential was assessed also after the supplementation with the potent and selective PPARγ antagonist T0070907 (1 μM) [38]. After 7 days in culture, a sufficient time for adipocyte differentiation and lipid droplet formation [39–41], cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 1 h and stained with Oil Red O (Sigma-Aldrich). Total counts of positive cells were performed, and the number of positive cells was expressed as the percentage to the total cells. To quantify the intracellular lipid accumulation of Oil Red O, the stained lipid droplets were eluted with 100% isopropanol for 10 min. The optical density was measured at 520 nm by a spectrophotometer [41]. These evaluations were performed by means of the software ImageJ (NIH).

2.7. RNA Extraction and Real-Time PCR

For gene expression analysis, cells were plated at a density of 6000 cells/cm2 and induced to differentiate for 7 days. Total RNA was extracted using a TRIZOL® reagent (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer's instructions and then quantified (NanoPhotometer® NP80, Implen). Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real-Time PCR was performed with the StepOnePlus™ Real-Time RT-PCR System (Thermo Fisher) using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Primers were designed using the NCBI's Primer-BLAST and are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Gene expression was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method, and GAPDH was used as a housekeeping gene.

2.8. Statistics

Results are expressed as the means ± SD and analysed using GraphPad Prism software (version 5.0, GraphPad Software, San Diego, California). Two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test was used to analyse normally distributed data. When three or more value sets were compared, one-way ANOVA was used followed by Tukey's posttest applied. The statistical significance was accepted for a p value < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Proliferation

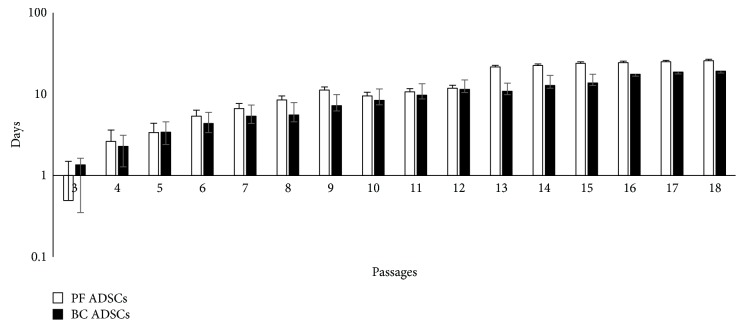

BC ADSC and PF ADSC proliferation was studied with cumulative population doubling (CPD) curves (Figure 1). The cellular proliferative activity gradually increased with the progression in the number of passages reaching a plateau at around passage 13 in PF ADSCs and around passage 16 in BC ADSCs. This indicates that BC and PF ADSCs have a similar proliferating activity.

Figure 1.

Long-term multipassage cultures of BC ADSCs and PF ADSCs. The graph shows a cumulative population doubling (CPD) across multiple consecutive passages (mean ± SD; n = 5). The cells were plated at a density of 7000 cell/cm2 and counted in triplicate by trypan blue exclusion at 85% confluence.

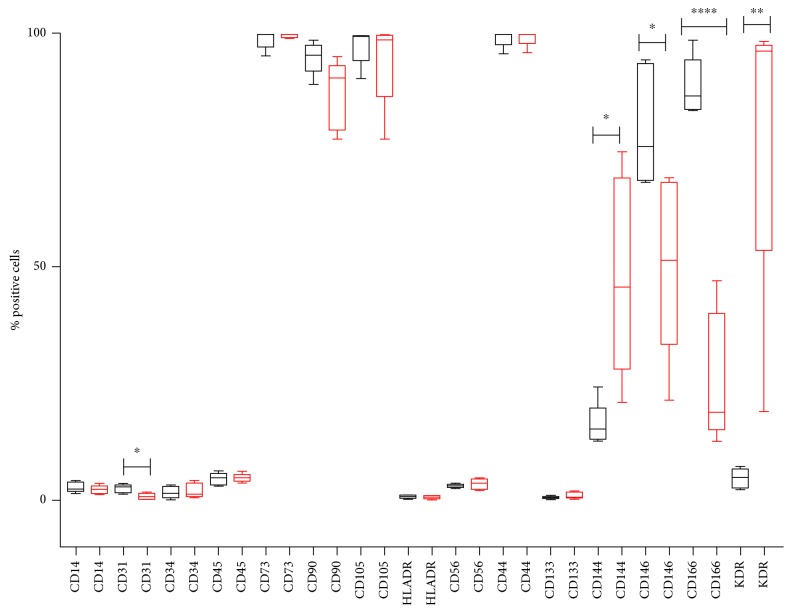

3.2. Phenotypic Characterization of PF and BC ADSCs

To evaluate the phenotypic features of the primary cultures, flow cytometry analysis of the two cellular populations was performed. We evaluated the expression of mesenchymal surface markers (CD73, CD90, and CD105), hematopoietic markers (CD14, CD45, CD56, and CD133), D-related human leukocyte antigen (HLA-DR), endothelial markers (CD31 and CD34), adhesion surface markers (CD144, CD44, CD146, and CD166), and receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor 2 (VEGFR2 also known as KDR). The evaluation was performed in triplicate at passage 4 for all investigated isolates (Supplementary Figure 1). Figure 2 shows the characterization of surface markers restricted to five isolates for each group, PF and BC ADSCs, which were used for all the in vitro experiments. PF and BC ADSCs strongly express the mesenchymal markers CD73 and CD105, with similar levels (close to 100%), and CD90, which is slightly less present in BC ADSCs. Few cells in both groups were positive to the hematopoietic markers CD14, CD45, and CD56; to the endothelial markers CD31 and CD34; and to HLA-DR and CD133. The percentage of cells positive to CD44 was very high (close to 100%), in both cell types. The adhesion surface marker CD144 and the receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor 2 (KDR) were significantly more expressed in BC ADSCs. On the contrary, CD146 and CD166 (adhesion surface markers) were significantly more expressed in PF ADSCs than BC ADSCs.

Figure 2.

Cell surface phenotype of 5 PF ADSCs (black boxes) and 5 BC ADSCs (red boxes). All percentages were obtained by flow cytometry analysis. Results were obtained from three independent experiments for each isolate. The statistical significance was determined by Student's t-test; ∗∗∗∗ p < 0.0001, ∗∗ p < 0.01, and ∗ p < 0.05 vs. PF ADSCs.

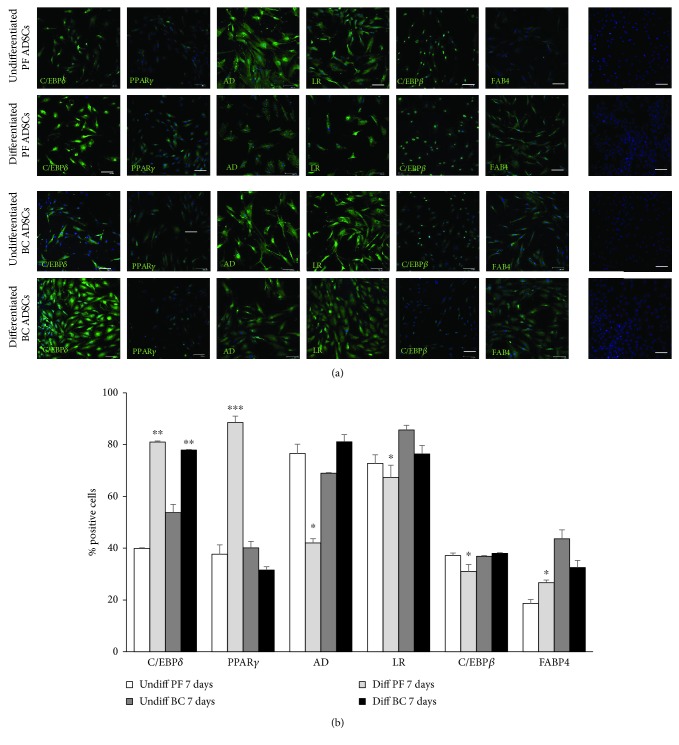

3.3. Expression of Adipogenic Markers in BC and PF ADSCs

PF and BC ADSCs were induced to differentiate with adipogenic medium for 7 days and then compared to nondifferentiated cells (cells grown in standard maintenance medium). After 7 days of adipogenic induction, the expression of differentiation markers was investigated by immunofluorescence with specific antibodies. A statistically significant increase of C/EBPδ expression, a marker of preadipocyte stages, was observed in both PF and BC ADSCs induced to differentiate compared to cells grown in control medium (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)). Localization of C/EBPδ was greatly increased in the nuclei of both differentiated ADSCs. Adipogenic differentiation caused the increase of PPARγ expression, an active modulator of lipid metabolism, only in PF ADSCs. The levels of this factor in BC under adipogenic stimulation were comparable to control standard culture conditions (undifferentiated cells). The expression of adiponectin was reduced in PF-differentiated ADSCs while it was slightly increased in BC ADSCs induced to differentiate. Leptin receptor and C/EBPβ expression in PF-differentiated ADSCs was decreased compared to the same cells maintained in control conditions. No significant variation was found for the leptin receptor and C/EBPβ in BC ADSCs induced to differentiate compared to control BC ADSCs. The levels of FABP4, a regulator of fatty acid, increased in differentiated PF ADSCs whereas its expression decreased in differentiated BC ADSCs. Together, these results suggest an impairment in adipogenic differentiation capabilities of BC ADSCs compared to PF ADSCs.

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescence analysis of ADSC marker expression after 7 days of culture in standard medium (undifferentiated ADSCs) and in adipogenic differentiation medium (differentiated ADSCs). (a) Immunofluorescence assay for C/EBPδ, PPARγ, adiponectin (AD), leptin receptor (LR), C/EBPβ, and FAB4 (green labelling) which are markers of adipogenesis progression. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue labelling). Negative control isotype staining was performed using normal goat serum in place of the primary antibody. Scale bars: 50 μm. (b) Quantification of cell positivity to adipogenic markers. The number of positive cells, expressed as the percentage to the total cell number given by DAPI nuclear staining, was calculated as an average of 15 different fields for each marker (3 fields/isolate). Error bars represent the SEM for three experiments. The statistical significance was determined by Student's t-test; ∗ p < 0.05 vs. undifferentiated ADSCs; ∗∗ p < 0.01 vs. undifferentiated ADSCs; ∗∗∗ p < 0.001 vs. undifferentiated ADSCs.

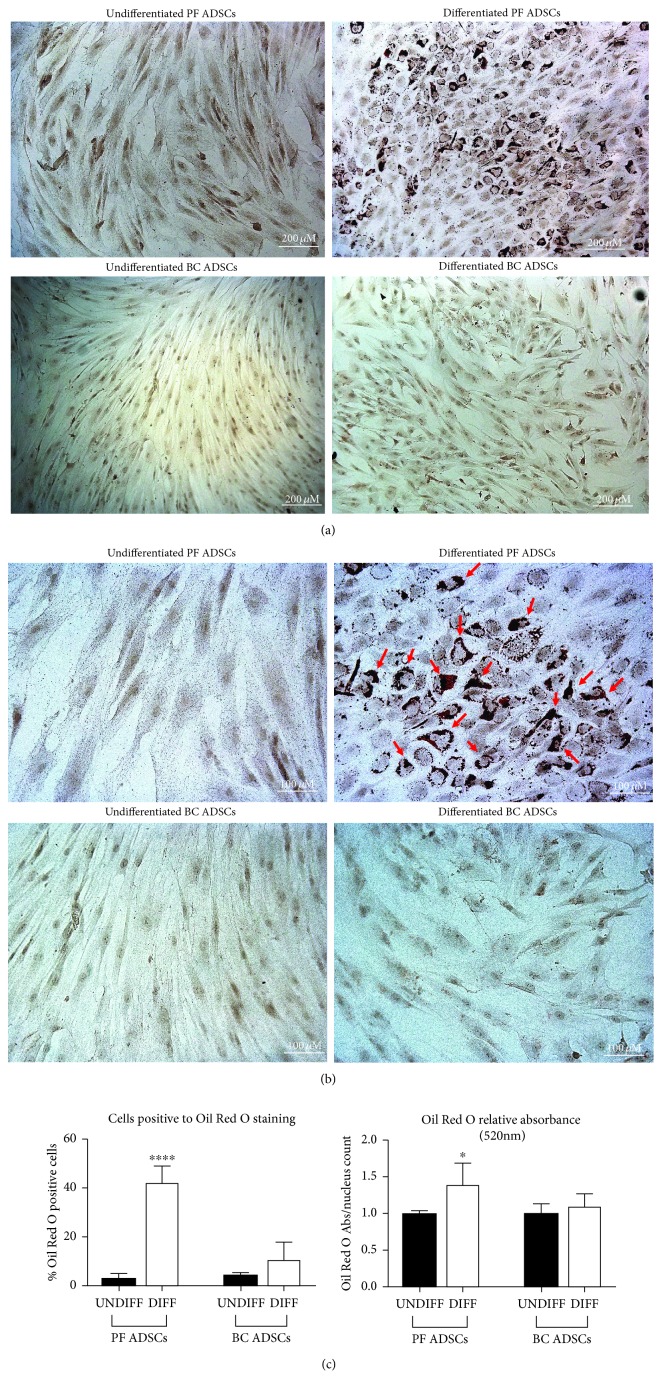

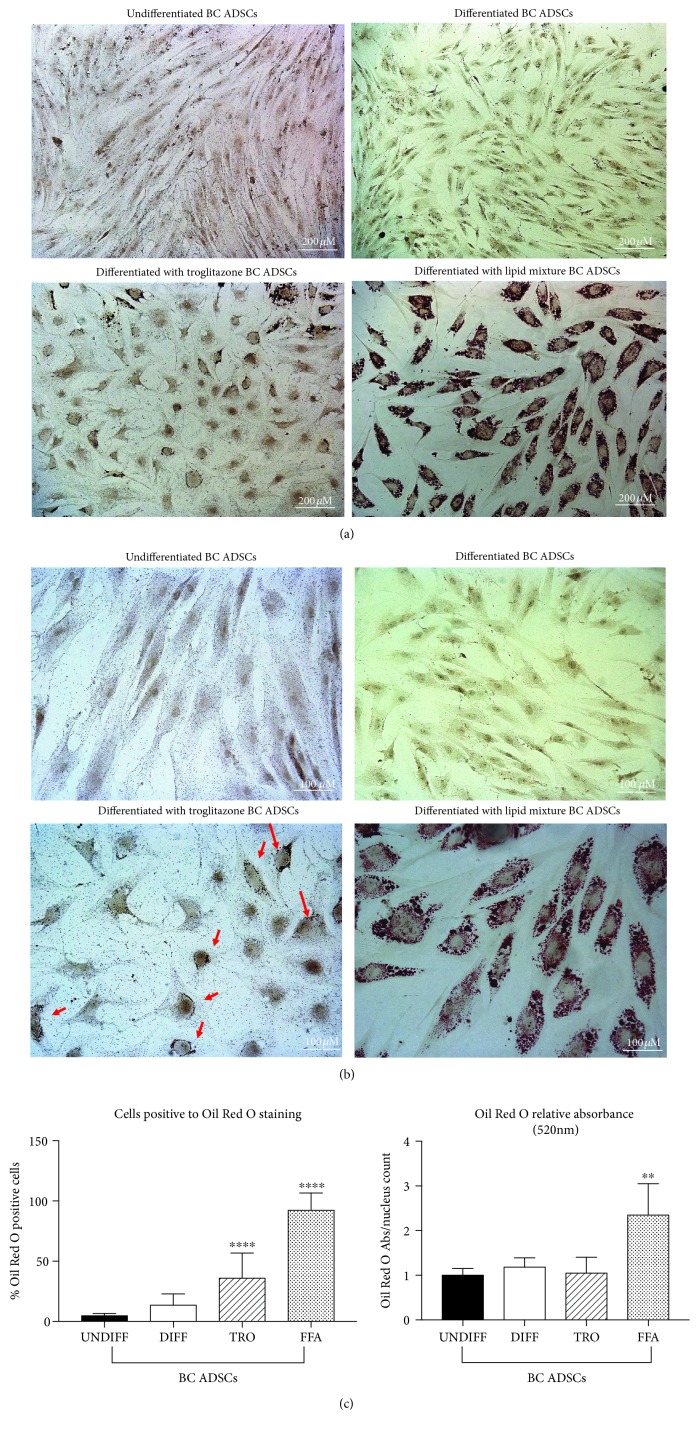

To investigate further the possible impairment of BC ADSC adipogenesis, the efficiency of the process was evaluated with Oil Red O staining in order to examine the lipid droplet formation. Indeed, Oil Red O staining (red colour) accumulated in lipid droplets in PF ADSCs, indicating a successful differentiation (Figures 4(a) and 4(b)). The quantification of both Oil Red O-positive cells and optical density after its extraction was analysed. As expected, PF ADSCs differentiated and presented a higher lipid accumulation compared to the control (Figure 4). More than 45% of differentiated PF ADSCs resulted positive to the Oil Red O staining. The quantification of lipid accumulation obtained by measuring the absorbance at 520 nm after the extraction procedure confirmed these observations. Interestingly, the BC ADSCs induced to differentiate did not present lipid droplet accumulation, suggesting that the standard adipogenic medium is insufficient to ensure successful differentiation (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Adipogenesis was revealed by Oil Red O staining for lipid droplet accumulation. (a) Representative images of PF ADSCs and BC ADSCs in control conditions and after adipogenic differentiation for 7 days (differentiated ADSCs). Scale bars: 200 μm. Data are representatives of five different isolates. (b) Magnifications of (a) images of PF ADSCs and BC ADSCs in control conditions and after adipogenic differentiation for 7 days (differentiated ADSCs). Accumulation of lipid droplets, stained with Oil Red O, is highlighted with red arrows. Scale bars: 100 μm. Data are representatives of five different isolates. (c) Percentage of cells positive to Oil Red O staining and quantification of Oil Red O extracted from lipid droplets measured at 520 nm normalized over nucleus counts. Data are reported as the mean ± SD of 5 different isolates. The statistical significance was determined by Student's t-test; ∗∗∗∗ p < 0.0001 and ∗ p < 0.05 vs. UNDIFF PF ADSCs.

3.4. Effect of PPARγ Stimulation and Nutritional Supplementation on BC ADSC Differentiation Capabilities

The observation that BC ADSCs seem to present a different and reduced differentiation ability compared to PF ADSCs led us to investigate whether the process can be stimulated by exogenous factors such as situations when the adipogenic differentiation was exacerbated. To do so, we adopted two different differentiation protocols: the culture medium was supplemented in the first protocol with troglitazone (1 μg/mL; TRO), a potent PPARγ activator [36, 37], and in the second one with a lipid mixture of free fatty acids (10% v/v; FFA), used to mimic a high-fat diet [29]. The rationale is that there could be an altered PPARγ modulation, in line with literature reports indicating an alteration in PPARγ expression in breast cancer cells [20]. Furthermore, we wished to preliminarily identify a potential mechanism for the obesity correlation with breast cancer [25–28]. The accumulation of lipid droplets, investigated by Oil Red O staining, was increased in both conditions, and this is significantly relevant when the lipid mixture was added (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of PPARγ activation and FFA supplementation on BC ADSC differentiation. (a) Adipogenesis was revealed by Oil Red O staining for lipid droplets. (a) shows representative images of BC ADSCs in control conditions and after adipogenic differentiation for 7 days with three different protocols (differentiated BC ADSCs, differentiated BC ADSCs with troglitazone, and differentiated BC ADSCs with lipid mixture). Data are representatives of 5 different isolates. Scale bars: 200 μm. (b) Magnifications of (a) images of BC ADSCs in control conditions and after adipogenic differentiation for 7 days with three different protocols (differentiated BC ADSCs, differentiated BC ADSCs with troglitazone, and differentiated BC ADSCs with lipid mixture). Minimal lipid droplet accumulation after troglitazone supplementation is highlighted by red arrows. Data are representatives of 5 different isolates. Scale bars: 100 μm. (c) Percentage of cells positive to Oil Red O staining and quantification of Oil Red O extracted from lipid droplets measured at 520 nm normalized over nucleus counts. Data are reported as the mean ± SD of 5 different isolates; the statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. ∗∗∗∗ p < 0.0001 and ∗∗ p < 0.01 vs. UNDIFF BC ADSCs.

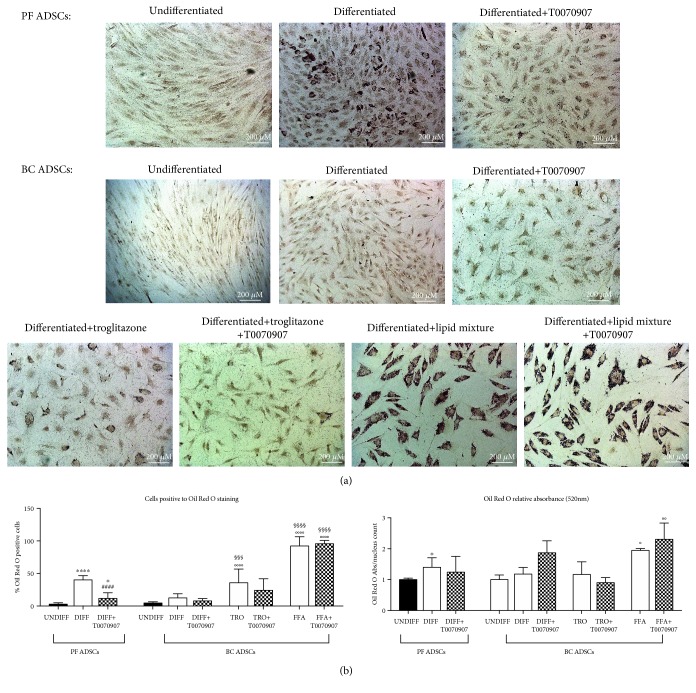

3.5. Effect of PPARγ Pharmacologic Inhibition on BC ADSC Differentiation Capabilities

Following the observation that BC ADSCs seem unresponsive to PPARγ canonical stimulation, we aimed to clarify whether this was true also for the receptor's inhibition. The treatment with the potent and selective PPARγ antagonist T0070907 (1 μM) [38], added to the medium supplemented with troglitazone or FFA, was not able to significantly counteract the lipid droplet accumulation in BC ADSCs (Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure 2). Both the extracted Oil Red O and the percentage of differentiated cells resulted unaffected by the application of T0070907 (Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure 2). As the control of the experiments, T0070907, at the same concentration, was also added to the differentiating medium of PF ADSCs. In this control case, the potent inhibitory effect was appreciable (Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure 2). The demonstration that T0070907 is effective in PF ADSCs but leaves BC ADSCs unaffected again supports the idea that these cells are unresponsive to PPARγ canonical activation.

Figure 6.

The effect of PPARγ inhibition on PF and BC ADSC differentiation. (a) Adipogenesis was revealed by Oil Red O staining for lipid droplets. (a) shows representative images of PF ADSCs and BC ADSCs in control conditions, after adipogenic differentiation for 7 days and after adipogenic differentiation for 7 days with the PPARγ inhibitor T0070907. Data are representatives of 5 different isolates. Scale bars: 200 μm. (b) Percentage of cells positive to Oil Red O staining and quantification of Oil Red O extracted from lipid droplets measured at 520 nm normalized over nucleus counts. Data are reported as the mean ± SD of 5 different isolates; the statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. ∗∗∗∗ p < 0.0001 and ∗∗ p < 0.01 vs. UNDIFF PF ADSCs; #### p < 0.0001 vs. DIFF PF ADSCs; °°°°p < 0.0001, °°p < 0.01, and °p < 0.05 vs. UNDIFF BC ADSCs; §§§§ p < 0.0001 and §§§ p < 0.001 vs. DIFF BC ADSCs.

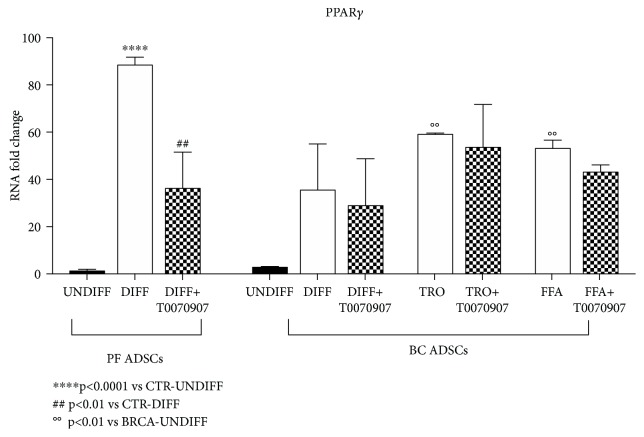

To confirm the evidences reported above, the expression of PPARγ was analysed by real-time PCR in order to verify the molecular changes occurring in the cells during the differentiation process. As expected, in differentiated PF ADSCs, PPARγ mRNA was significantly increased and, conversely, resulted downregulated when cells were also treated with the PPARγ inhibitor (Figure 7). In BC ADSCs, the increase of the adipogenic master gene was observed only when cells were supplemented with troglitazone or FFA (Figure 7). The presence of the inhibitor T007097 did not alter PPARγ expression in BC ADSCs. This suggests that a protocol mimicking nutritional supplementation with a high-fat diet has the ability to modify the genetic profile and differentiation capabilities of BC ADSCs but that this activation is potentially unaffected by PPARγ activity.

Figure 7.

The effect of troglitazone and nutritional supplementation on the expression of PPARγ mRNA. The graph shows BC ADSCs in control conditions and after adipogenic differentiation for 7 days with three different protocols (differentiated BC ADSCs±T0070907, differentiated BC ADSCs with troglitazone±T0070907, and differentiated BC ADSCs with lipid mixture±T0070907). PF ADSCs were inserted as a positive control. The expression of PPARγ mRNA was analysed by real-time PCR. The results are an average of five different isolates, and data are reported as the mean ± SD (n = 5). The statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA; ∗∗∗∗ p < 0.001 vs. undifferentiated PF ADSCs; ## p < 0.01 vs. undifferentiated PF ADSCs; °°p < 0.01 vs. undifferentiated BC ADSCs.

4. Discussion

This study is aimed at comparing the features of ADSCs isolated from the adipose tissue of breast cancer- (BC-) bearing patients with ADSCs isolated from PF of cancer-free patients, considered here controls. The project stems from various lines of evidences suggesting a role for BC ADSCs during tumour progression and relapse processes. It has been demonstrated that the interactions between cancer and its local microenvironment can determine features such as growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis [11, 12]. Even so, the effects of MSCs on cancer cells are controversial, with evidences indicating the promotion of metastasis and other inhibitions of cancer cell invasion and growth induced by MSCs [42, 43]. The cross-talk between a tumour microenvironment and cancer cells has been characterized both in animal experimental models [10] and in in vitro MDA-MB-231 cells [12], demonstrating that the tumour and its microenvironment create an intertwined loop favouring tumour progression. Mesenchymal stem cells can be regulators of this process, as evidences show their role in promoting breast cancer metastasis [11]. Further, elucidating the cellular features of ADSCs surrounding the tumour microenvironment could be of crucial importance in the modulation of the tumour itself.

We observed that in vitro expanded PF and BC ADSCs displayed different characteristics in terms of adipogenic marker expression and phenotypical features of differentiation. This is, to our knowledge, the first study describing the phenotypic characterization of PF and BC ADSCs along with their adipogenic differentiation. Since during differentiation the proliferation of BC ADSCs slowed down shortly with a high rate of mortality (data not shown), 7 days was considered an adequate time to study the process. MSCs are known to show negative expression of hematopoietic surface markers, cluster of differentiation (CD34, CD45, and HLA-DR), and endothelial marker (CD31) but high expressions of CD73, CD90, and CD105 [44]. CD45 is found in hematopoietic cells and regulates cell growth, differentiation, mitotic cycle, and oncogenic transformation [45]. CD90 is a membrane-bound glycoprotein which is expressed by almost 90% of variable tissues, and its function is related to angiogenesis [46]. Consistent with literature reports, almost all of the PF and BC ADSCs express surface markers related to MSCs at very high levels (close to 100%) without any difference depending of the source, while the endothelial and hematopoietic markers were detected only in a small percentage. The slightly lower (but still high) levels of CD90 expression in BC ADSCs compared to PF ADSCs might be caused by the high variability between samples. CD144 (VE-cadherin) is an adhesion protein expressed in endothelial cells. Molecules associated with angiogenesis and vasculogenesis, including this marker, are usually found strongly upregulated in aggressive cancers [47, 48], consistent with our observations. CD146, a typical adhesion marker, is reported as a common surface marker of MSCs, and the activation of CD146 induces the dynamic process of dimerization in response to stimuli in a tumour microenvironment [49]. Indeed, the biological significance of CD146 in a normal tissue remains unclear, even if it has been suggested to have a fundamental role in cancer, angiogenesis, and cardiovascular diseases [50]. It has been reported that the surface markers such as CD133, in combination with CD29/CD24 and CD44/CD166, may correlate with high Wnt activity and identify stem cells in various tumour types and their possible interaction with the microenvironment [51]. Interestingly, in BC ADSCs, the markers CD144, CD146, CD166, and KDR result significantly deregulated suggesting oncogenic alteration also in the tumour microenvironment with a possible role in favouring angiogenesis, tumour cell migration, and proliferation [52].

Adipogenic differentiation is regulated by a complex network of transcription factors. It begins with increased expressions of CCAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP), which in turn activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) [53]. In mammalian cells, the PPARγ and the C/EBPs such as C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, and C/EBPδ are considered the key early regulators of adipogenesis, while fatty acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4), adiponectin, and fatty acid synthase (FAS) are responsible for the formation of mature adipocytes [54]. It is reported that FABP4 is an adipokine with a distinct role of transcriptional and metabolic regulation in ASCs [55]. FABP4 is increased during the differentiation only in PF ADSCs, and interestingly, its expression decreases when BC ADSCs are induced to differentiate. PF ADSCs show a significant increase of PPARγ during the adipogenic differentiation, in accordance with other works stating that PPARγ is directly associated with lipid metabolism. On the other hand, in BC ADSCs induced to differentiate, PPARγ does not show a significant difference with the undifferentiated cells. This is confirmed with multiple techniques, observing a phenotypic (immunohistochemistry) and genetic (real-time PCR) incapability of these cells to express the PPARγ receptor and thus efficiently differentiate. Indeed, BC ADSCs show an impaired ability compared to PF ADSCs to differentiate into adipocytes. At this stage of differentiation, no differences were observed for C/EBPβ while C/EBPδ was increased in both cellular populations, as expected.

The observations indicating an impaired differentiation ability of BC ADSCs, together with literature reports describing PPARγ deregulation in breast cancer patients and its possible role as a therapeutic target [20–23], lead us to further investigate the role that this receptor could play in BC ADSC differentiation. To this end, we attempted to stimulate BC ADSC differentiation with the supplementation of the PPARγ activator troglitazone [37]. We found that this slightly increases BC ADSC adipogenic differentiation but that this increase is not impaired following the supplementation with the PPARγ inhibitor T007097, supporting the claim that BC ADSCs are partially insensitive to PPARγ modulation. We hypothesise that troglitazone could also mediate PPARγ-independent effects on BC ADSCs but the identification of a specific activated pathway would require further analysis. Interestingly, previous literature reports demonstrate that troglitazone inhibited telomerase activity in MDA-MB-231 cells, independently of PPARγ activity [56].

Moreover, we decided to investigate the concept that nutrients and obesity may have in BC progression [9, 16], evaluating the effects of a high-fat diet on the differentiation properties of BC ADSCs. The aim was to gain more in depth insight into epidemiologic and experimental evidences suggesting the role of nutritional health and high/low-fat diets in the regulation of breast cancer prognosis [16, 24–28]. The results obtained were very interesting, demonstrating a significant lipid accumulation and also a significant increase in PPARγ expression. This observation could support the evidences that nutrition influences the breast cancer microenvironment, and targeting this pathway may be of key importance in modulating tumour progression. In the experimental context of BC ADSCs, the PPARγ inhibitor T007097 was proved inefficient in modulating BC ADSC adipogenesis after lipid mixture supplementation.

Together, these results indicate that BF ADSCs are unable to differentiate when stimulated with a standard protocol, but this can be partially overcome by supplementing the differentiation medium with troglitazone or FFA. The demonstration that BC ADSCs were proved unresponsive to the PPARγ inhibitor T007097 further supports the hypothesis that this receptorial signalling is partially impaired in these cells, although further experimental analyses are required to elucidate the specific intracellular pathways activated.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study shows that there is a significant difference between healthy fat tissue and fat tissue of BC-bearing patients when observing molecular marker expression, phenotype, and adipogenic differentiation capability. Indeed, BC ADSCs present with an impaired differentiation efficiency. The present study also shows some preliminary, although very interesting, results correlating the role of nutrition on a tumourigenic microenvironment, but more studies are necessary to elucidate the precise mechanisms. Furthermore, the observation of BC ADSC unresponsiveness to PPARγ canonical stimulation and inhibition could provide evidence of new deregulated and targetable cancer pathways. This is the first study that characterizes ADSCs from fat tissue near the breast cancer and compares them with ADSCs derived from periumbilical fat. Furthermore, for the first time, the adipogenic differentiation potential of BC ADSCs was studied. With these promising results, further studies aiming at clarifying the mechanism of adipogenic differentiation from the BC microenvironment and its role in BC development could be of crucial importance in the understanding of breast cancer progression and metastasis.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Pediatric Clinical Research Center Fondazione “Romeo and Enrica Invernizzi” to AMDG. Federica Rey would like to thank the Fondazione Fratelli Confalonieri for the financial support during her PhD.

Contributor Information

Stephana Carelli, Email: stephana.carelli@guest.unimi.it.

Anna Maria Di Giulio, Email: annamaria.digiulio@unimi.it.

Data Availability

Primary cultures were obtained from PF and from mammary fat, isolated from patients at University San Paolo Hospital of Milan (Milan, Italy). All data are provided in full in results of our manuscript, and the necessary detail can be provided by the corresponding authors under request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests.

Authors' Contributions

Federica Rey and Elena Lesma contributed equally to this work. All the contributing authors have seen and approved the manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: list of primer sequences. Supplementary Figure 1: cell surface phenotype of 20 BC ADSCs (red boxes) and 8 PF ADSCs (black boxes). All percentages were obtained by flow cytometry analysis. Results were obtained from three independent experiments. The statistical significance was determined by Student's t-test; ∗∗∗∗ p < 0.0001, ∗∗∗ p < 0.001, ∗∗ p < 0.01, and ∗ p < 0.05 vs. PF ADSCs. Supplementary Figure 2: adipogenesis was revealed by Oil Red O staining for lipid droplets. The panel shows image magnifications of Figure 6(a), showing PF ADSCs and BC ADSCs in control conditions and after adipogenic differentiation for 7 days ± PPARγ inhibitor T0070907. Data are representatives of 5 different isolates. Scale bars: 100 μm.

References

- 1.Hosseini S., Naderi-Manesh H., Vali H., et al. Contribution of osteocalcin-mimetic peptide enhances osteogenic activity and extracellular matrix mineralization of human osteoblast-like cells. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2019;173:662–671. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzsimmons R. E. B., Mazurek M. S., Soos A., Simmons C. A. Mesenchymal stromal/stem cells in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. Stem Cells International. 2018;2018:16. doi: 10.1155/2018/8031718.8031718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nepali S., Park M., Lew H., Kim O. Comparative analysis of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells from orbital and abdominal fat. Stem Cells International. 2018;2018:9. doi: 10.1155/2018/3932615.3932615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Stefano A. B., Grisafi F., Castiglia M., et al. Spheroids from adipose-derived stem cells exhibit an miRNA profile of highly undifferentiated cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2018;233(11):8778–8789. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubey N. K., Mishra V. K., Dubey R., Deng Y. H., Tsai F. C., Deng W. P. Revisiting the advances in isolation, characterization and secretome of adipose-derived stromal/stem cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018;19(8):p. 2200. doi: 10.3390/ijms19082200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carelli S., Colli M., Vinci V., Caviggioli F., Klinger M., Gorio A. Mechanical activation of adipose tissue and derived mesenchymal stem cells: novel anti-inflammatory properties. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018;19(1):p. 267. doi: 10.3390/ijms19010267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carelli S., Giallongo T., Rey F., et al. Neuroprotection, recovery of function and endogenous neurogenesis in traumatic spinal cord injury following transplantation of activated adipose tissue. Cell. 2019;8(4):p. 329. doi: 10.3390/cells8040329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ritter A., Friemel A., Fornoff F., et al. Characterization of adipose-derived stem cells from subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissues and their function in breast cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6(33):34475–34493. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radisky E. S., Radisky D. C. Stromal induction of breast cancer: inflammation and invasion. Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders. 2007;8(3):279–287. doi: 10.1007/s11154-007-9037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karnoub A. E., Dash A. B., Vo A. P., et al. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449(7162):557–563. doi: 10.1038/nature06188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albarenque S. M., Zwacka R. M., Mohr A. Both human and mouse mesenchymal stem cells promote breast cancer metastasis. Stem Cell Research. 2011;7(2):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mi Z., Bhattacharya S. D., Kim V. M., Guo H., Talbot L. J., Kuo P. C. Osteopontin promotes CCL5-mesenchymal stromal cell-mediated breast cancer metastasis. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(4):477–487. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soysal S. D., Tzankov A., Muenst S. E. Role of the tumor microenvironment in breast cancer. Pathobiology. 2015;82(3-4):142–152. doi: 10.1159/000430499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeGennaro V., Jr., Jiwani F., Patberg E., et al. Epidemiological, clinical, and histopathological features of breast cancer in Haiti. Journal of Global Oncology. 2018;4(4):1–9. doi: 10.1200/jgo.17.00135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reis-Filho J. S., Pusztai L. Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: classification, prognostication, and prediction. The Lancet. 2011;378(9805):1812–1823. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61539-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cazzaniga M., Bonanni B. Relationship between metabolic disorders and breast cancer incidence and outcomes. Is there a preventive and therapeutic role for berberine? Anticancer Research. 2018;38(8):4393–4402. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng Y., Spezia M., Huang S., et al. Breast cancer development and progression: risk factors, cancer stem cells, signaling pathways, genomics, and molecular pathogenesis. Genes & Diseases. 2018;5(2):77–106. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mailey B., Hosseini A., Baker J., et al. Adipose-derived stem cells: methods for isolation and applications for clinical use. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2014;1210:161–181. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1435-7_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lefterova M. I., Haakonsson A. K., Lazar M. A., Mandrup S. PPARγ and the global map of adipogenesis and beyond. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2014;25(6):293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badawi A. F., Badr M. Z. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ and levels of prostaglandin E2 and 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 in human breast cancer and metastasis. International Journal of Cancer. 2003;103(1):84–90. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Youssef J., Badr M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and cancer: challenges and opportunities. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2011;164(1):68–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong F., Xu P., Zhai Y. The opportunities and challenges of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors ligands in clinical drug discovery and development. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018;19(8):p. 2189. doi: 10.3390/ijms19082189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lakshmi S. P., Reddy A. T., Banno A., Reddy R. C. PPAR agonists for the prevention and treatment of lung cancer. PPAR Research. 2017;2017:8. doi: 10.1155/2017/8252796.8252796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu L., Peterson L. L. The impact of diet on breast cancer outcomes. Current Nutrition Reports. 2019;8(3):212–221. doi: 10.1007/s13668-019-00278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker H. A., Fabian C. J., Hastings R. C., et al. Circulating adipose stromal cells as a response biomarker in phase II energy balance trials of obese breast cancer survivors and high-risk women. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2019;176(2):387–394. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ecker B. L., Lee J. Y., Sterner C. J., et al. Impact of obesity on breast cancer recurrence and minimal residual disease. Breast Cancer Research. 2019;21(1):p. 41. doi: 10.1186/s13058-018-1087-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee M. M., Lin S. S. Dietary fat and breast cancer. Annual Review of Nutrition. 2000;20(1):221–248. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Argolo D. F., Hudis C. A., Iyengar N. M. The impact of obesity on breast cancer. Current Oncology Reports. 2018;20(6):p. 47. doi: 10.1007/s11912-018-0688-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beyaz S., Mana M. D., Roper J., et al. High-fat diet enhances stemness and tumorigenicity of intestinal progenitors. Nature. 2016;531(7592):53–58. doi: 10.1038/nature17173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camargo A., Rangel-Zúñiga O. A., Alcalá-Díaz J., et al. Dietary fat may modulate adipose tissue homeostasis through the processes of autophagy and apoptosis. European Journal of Nutrition. 2017;56(4):1621–1628. doi: 10.1007/s00394-016-1208-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Canazza A., Bedini G., Caremoli F., et al. A novel efficient method to isolate human adipose-derived stromal cells from periumbilical biopsies without enzymatic digestion. CellR4. 2015;3(1, article e1397) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dominici M., le Blanc K., Mueller I., et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bourin P., Bunnell B. A., Casteilla L., et al. Stromal cells from the adipose tissue-derived stromal vascular fraction and culture expanded adipose tissue-derived stromal/stem cells: a joint statement of the International Federation for Adipose Therapeutics and Science (IFATS) and the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) Cytotherapy. 2013;15(6):641–648. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawaji A., Ohnaka Y., Osada S., Nishizuka M., Imagawa M. Gelsolin, an actin regulatory protein, is required for differentiation of mouse 3T3-L1 cells into adipocytes. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2010;33(5):773–779. doi: 10.1248/bpb.33.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carelli S., Messaggio F., Canazza A., et al. Characteristics and properties of mesenchymal stem cells derived from microfragmented adipose tissue. Cell Transplantation. 2015;24(7):1233–1252. doi: 10.3727/096368914X681603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galateanu B., Dinescu S., Cimpean A., Dinischiotu A., Costache M. Modulation of adipogenic conditions for prospective use of hADSCs in adipose tissue engineering. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2012;13(12):15881–15900. doi: 10.3390/ijms131215881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hausman G. J., Dodson M. V., Ajuwon K., et al. Board-invited review: the biology and regulation of preadipocytes and adipocytes in meat animals. Journal of Animal Science. 2009;87(4):1218–1246. doi: 10.2527/jas.2008-1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee G., Elwood F., McNally J., et al. T0070907, a selective ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, functions as an antagonist of biochemical and cellular activities. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(22):19649–19657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee M. J., Fried S. K. Optimal protocol for the differentiation and metabolic analysis of human adipose stromal cells. Methods in Enzymology. 2014;538:49–65. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800280-3.00004-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsumoto T., Kano K., Kondo D., et al. Mature adipocyte-derived dedifferentiated fat cells exhibit multilineage potential. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2008;215(1):210–222. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang Y., Jin C., Zheng Y., et al. Knockdown of lncRNA MIR31HG inhibits adipocyte differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells via histone modification of FABP4. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):p. 8080. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08131-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin W., Huang L., Li Y., et al. Mesenchymal stem cells and cancer: clinical challenges and opportunities. BioMed Research International. 2019;2019:12. doi: 10.1155/2019/2820853.2820853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Papaccio F., Paino F., Regad T., Papaccio G., Desiderio V., Tirino V. Concise review: cancer cells, cancer stem cells, and mesenchymal stem cells: influence in cancer development. Stem Cells Translational Medicine. 2017;6(12):2115–2125. doi: 10.1002/sctm.17-0138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang L., Li Z. Y., Wang Y. P., Wu Z. H., Yu B. Dynamic expression profiles of marker genes in osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal. 2015;30(2):108–113. doi: 10.1016/S1001-9294(15)30021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Furlan G., Minowa T., Hanagata N., Kataoka-Hamai C., Kaizuka Y. Phosphatase CD45 both positively and negatively regulates T cell receptor phosphorylation in reconstituted membrane protein clusters. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2014;289(41):28514–28525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.574319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shaikh M. V., Kala M., Nivsarkar M. CD90 a potential cancer stem cell marker and a therapeutic target. Cancer Biomarkers. 2016;16(3):301–307. doi: 10.3233/CBM-160590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hendrix M. J. C., Seftor E. A., Hess A. R., Seftor R. E. B. Vasculogenic mimicry and tumour-cell plasticity: lessons from melanoma. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2003;3(6):411–421. doi: 10.1038/nrc1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Y., Li F., Yang Y. T., et al. IGFBP2 promotes vasculogenic mimicry formation via regulating CD144 and MMP2 expression in glioma. Oncogene. 2019;38(11):1815–1831. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0525-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bu P., Zhuang J., Feng J., Yang D., Shen X., Yan X. Visualization of CD146 dimerization and its regulation in living cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 2007;1773(4):513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ouhtit A., Gaur R. L., Abd Elmageed Z. Y., et al. Towards understanding the mode of action of the multifaceted cell adhesion receptor CD146. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer. 2009;1795(2):130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vermeulen L., de Sousa E Melo F., van der Heijden M., et al. Wnt activity defines colon cancer stem cells and is regulated by the microenvironment. Nature Cell Biology. 2010;12(5):468–476. doi: 10.1038/ncb2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang J., Ghosh J., Mohamad S. F., et al. CD166 engagement augments mouse and human hematopoietic progenitor function via activation of stemness and cell cycle pathways. Stem Cells. 2019 doi: 10.1002/stem.3053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhuang H., Zhang X., Zhu C., et al. Molecular mechanisms of PPAR-γ governing MSC osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation. Current Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2016;11(3):255–264. doi: 10.2174/1574888X10666150531173309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moseti D., Regassa A., Kim W. K. Molecular regulation of adipogenesis and potential anti-adipogenic bioactive molecules. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2016;17(1):p. 124. doi: 10.3390/ijms17010124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Floresta G., Pistarà V., Amata E., et al. Adipocyte fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4) inhibitors. A comprehensive systematic review. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2017;138:854–873. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rashid-Kolvear F., Taboski M. A. S., Nguyen J., Wang D. Y., Harrington L. A., Done S. J. Troglitazone suppresses telomerase activity independently of PPARγ in estrogen-receptor negative breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2010;10(1):p. 390. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: list of primer sequences. Supplementary Figure 1: cell surface phenotype of 20 BC ADSCs (red boxes) and 8 PF ADSCs (black boxes). All percentages were obtained by flow cytometry analysis. Results were obtained from three independent experiments. The statistical significance was determined by Student's t-test; ∗∗∗∗ p < 0.0001, ∗∗∗ p < 0.001, ∗∗ p < 0.01, and ∗ p < 0.05 vs. PF ADSCs. Supplementary Figure 2: adipogenesis was revealed by Oil Red O staining for lipid droplets. The panel shows image magnifications of Figure 6(a), showing PF ADSCs and BC ADSCs in control conditions and after adipogenic differentiation for 7 days ± PPARγ inhibitor T0070907. Data are representatives of 5 different isolates. Scale bars: 100 μm.

Data Availability Statement

Primary cultures were obtained from PF and from mammary fat, isolated from patients at University San Paolo Hospital of Milan (Milan, Italy). All data are provided in full in results of our manuscript, and the necessary detail can be provided by the corresponding authors under request.