Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To explore patient and caregiver experiences, preferences, and attitudes toward the provision and receipt of caregiving assistance with medical tasks.

DESIGN:

Qualitative study consisting of in-depth interviews with 20 patient–caregiver dyads.

SETTING:

Community and academic-affiliated primary care clinics.

PARTICIPANTS:

Individuals aged 65 or older with 2 or more health conditions and their family caregivers (n=20 patient–caregiver dyads).

MEASUREMENTS:

Open-ended questions were asked about the tasks that the patient and caregiver performed to manage the patient’s health conditions; questions were designed to elicit participant reactions and attitudes toward the help they provided or received. Transcripts were analyzed using the constant comparative method.

RESULTS:

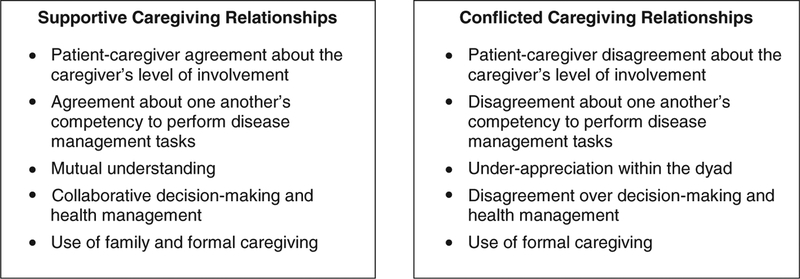

Participant preferences and attitudes toward the receipt and provision of disease management tasks were highly personal. Participant responses clustered into 2 caregiving typologies: supportive caregiving relationships and conflicted caregiving relationships. Supportive relationships were characterized by patient–caregiver agreement about caregiver level of involvement, agreement about one another’s competency to perform disease-related tasks, mutual understanding, collaborative decision-making and disease management, and use of family and formal caregiving. Conflicted relationships were characterized by disagreement about caregiver level of involvement, disagreement about one another’s competency to perform disease management tasks, underappreciation of one another’s experiences, disagreement over decision-making and disease management, and use of formal caregiving.

CONCLUSIONS:

The views that patient–caregiver dyads expressed in this study illustrate the varied preferences and attitudes toward caregiving assistance with multiple health conditions. These findings support a dyadic approach to evaluating and addressing patient and caregiver needs and attitudes toward provision of assistance.

In the United States, 4 out of 5 older adults have multiple chronic health conditions.1 For many of these individuals, managing their conditions requires the active involvement of a family caregiver.2,3 Together, older adults and their caregivers attend doctors’ appointments,4 participate in treatment discussions,5 and provide the patient’s treatment plan at home.6

Studies of individuals with dementia and their caregivers have shown that conflicts in the caregiving relationship may arise from patients’ and caregivers’ competing concerns:7 specifically, the patient’s desire for autonomy and the caregiver’s concern for the patient’s safety.7–9 Although less is known about how individuals without cognitive impairment and their caregivers negotiate competing perspectives when managing chronic illness, recent qualitative research points to several problems that may exist. Individuals with acute coronary syndrome identified problematic behaviors of family and friends, including unwanted or excessive telephone contact and unsolicited advice.10 In another study, individuals with systemic lupus erythematosus reported receiving advice from friends and family that was perceived to be uninformed and support that was perceived as overprotective.11 Although these studies provide important insights into the patient’s perspective, a dyadic approach is necessary to understand patient and caregiver perspectives and the interpersonal dynamics within the caregiving relationship. Also needed is better understanding of these perspectives in a broader cross-section of individuals not selected according to the presence of a specific condition and their caregivers.

The present study used in-depth dyadic interviews to simultaneously explore patient and caregiver experiences, attitudes, and preferences regarding provision and receipt of caregiving assistance for chronic illness. It focused on older adults with multiple chronic conditions and their caregivers to capture a broad spectrum of patient needs and a wide representation of caregiving tasks.

METHODS

Participant Recruitment

Patients were recruited from academic-affiliated primary care and specialty clinics and from assisted living facilities in Connecticut. Seven clinicians and a social worker were asked to identify individuals aged 65 and older who had 2 or more chronic conditions, were not cognitively impaired, and had an unpaid caregiver (relative, friend) involved in their healthcare. The first author (CR) contacted individuals that the clinicians identified who confirmed their eligibility over the telephone. People were excluded if they had cognitive impairment, as identified by a score of 10 or greater on the Blessed Orientation Memory Concentration (BOMC)12 or the inability to articulate what health conditions they had, if their caregiver lived too far away to participate in an in-person interview, or if they were not fluent in English. Individuals who agreed to participate in the study were asked to provide contact information for the caregiver. Caregivers were screened over the telephone for their cognitive status (using the BOMC) and fluency in English.

Two authors (CR, LI) trained in qualitative interviewing conducted in-depth interviews at the patient’s residence with the patient and caregiver present. Interviews were conducted until theoretical saturation was reached.13 The institutional review board at the Yale School of Medicine determined that he research plan was exempt from review.

Data Collection

A discussion guide (Supplementary Appendix S1) was designed to elicit patient and caregiver perspectives regarding management of the patient’s health conditions. The initial version of the guide was pilot tested.

Patients were first asked to name their chronic conditions and then to describe the illness management activities that they performed to manage those conditions. Additional probes were used to elicit their reactions to the assistance they received. Caregivers were invited to respond to patients’ answers, provide their own examples, and discuss how they felt about the assistance they provided.

After the interview, patients completed a self-administered questionnaire that asked about age, sex, race, education, marital status, living arrangement, and relationship to their caregiver. Caregivers completed a separate questionnaire that asked about age, sex, race, education, marital and employment status, and living arrangement.

Data Analysis

The audio files were transcribed, and the transcripts were analyzed using the constant comparative method.13,14 Two investigators (CR, TRF) independently reviewed and coded an initial set of transcripts and then met to compare their codes, resolving disagreement through discussion.15,16 Once a final coding structure was in place, the two investigators independently coded four randomly selected transcripts; 80% agreement was achieved. A single investigator (C.R.) coded the remaining transcripts. The 2 investigators met again to examine the relationships between codes and group them within overarching themes. This included the development of a typology; deviant case analysis was used to search for examples that did not support the typology.14 Atlast-ti 7.5.10 (Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany) was used to assist with data management, organization, and analysis.

RESULTS

Patients had a mean age of 82.0±10.3, 89.5% were white, and 60.6% were female. Caregivers had a mean age of 69.3±16.6, 65.0% were female, and 40.0% were a spouse and 45.0% an adult child of the patient. Patient–caregiver dyads identified a common set of caregiving activities: managing medications, coordinating doctors’ appointments, managing paid caregivers, and speaking with medical professionals. Participant responses clustered into 2 caregiving typologies: supportive caregiving relationships and conflicted caregiving relationships (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of supportive and conflicted caregiving relationships.

Supportive Dyads

Agreement about caregiver level of involvement

Caregivers were responsive to patient requests for assistance and autonomy. In doctors’ visits, for example, caregivers were mindful of the patient’s desire to speak directly to the provider but asked clarifying questions to ensure that their own need for information was met (Table 1).

Table 1.

Themes Characterizing Supportive Caregiving Relationships

| Agreement about caregiver level of involvement | “Well, [patient] always asks me to be [in the doctor’s visit], and the doctors always ask her first. They ask her first if it is okay. I don’t ask if she doesn’t ask me first.” (#12 caregiver) |

| “That way I can depend on [caregiver]. I don’t have to depend on my own thinking or remembering. She does it.” (#12 patient) | |

| “I try to stay in the background [in doctors’ visits], but if there is something that I’m concerned about, I will ask a question” (#19 caregiver). | |

| “I want [caregiver] to be there to know and to understand what is going on so I don’t misinterpret something” (#19 patient). | |

| Agreement about one another’s competency to perform health-related tasks | “My peripheral vision and my depth perception is shot to hell…. I can’t read the labels, so I have [the pills] in the medicine cabinet in the same place…[Caregiver] knows what the medications are. She has gone to pick up my meds. Sometimes she will come to pick me up and drive me to the pharmacy to fill [the prescriptions].” (#19 patient) |

| “[Patient] still has the cognitive skills. It is just that he does not have the vision.” (#19 caregiver) | |

| “[Caregiver] makes sure that I take this [medication] and this [medication]. Sometimes I will stick the thing in my pocket and I think ‘I’ll take it later’ and then I forget about it or I’m just not in the mood to take a pill right then.” (#17 patient) | |

| “You can’t expect someone who is under this stress, dealing with several illnesses, the death of a daughter, and everything else that gets complicated in your life to be able to sit down and put in the amount of time that it takes to focus on [medication management]. You can’t expect someone to do that.” (#17 caregiver) | |

| Mutual understanding | “She has a much more restricted life…. People will say to me ‘How is your sister?’ And I say ‘Well, if you were asking [patient] that question right now she would tell you she is doing fine under the circumstances.’ By this I mean her life prior to this was entirely different because she was active, and her friends were all in New Hampshire.” (#12 caregiver) |

| “I try to do all the things that I am supposed to do because [caregiver] is making such an effort. She puts so much of an effort to get me on a path. I know that is not easy.” (#12 patient) | |

| Collaborative decision-making and disease management | “We discuss it. [Patient] says this is what is going to happen, and then I say ‘ok’ and then we discuss the situation.” (#11 caregiver) |

| “I have this hip problem, which is killing me. It hurts whether I am standing or sitting or sleeping…. I said ‘I want surgery,’and the doctor said ‘I don’t think so. I really don’t think, medically, you should have surgery,’ so I let it go at that. If he had said ‘Surgery, and yes you should do it’ then I talk to [caregiver] about it. (#11 patient) | |

| “[We] talked about [the surgery] before [patient] went [to the doctor’s visit]. We were driving somewhere, and [patient] said, ‘Okay, if they agree with surgery are you okay with it?” and I said, ‘Yes, as long as you are okay with it.’ And [patient] goes ‘If I don’t live through it I had a good life.’” (#11 caregiver) | |

| “We talk about things. It is not like she is in command or that I am in command. We discuss it. We’re like an old married couple. We discuss it.” (#15 patient) | |

| Use of family and formal caregiving | Family caregiving |

| “She is my sister and she kind of has something to say about what is going to happen to me in the end. I don’t want to give [caregiving] to a stranger.” (#9 patient) “I listen, and he tells me what he needs.” (#9 caregiver) | |

| Formal caregiving | |

| “So now [employing a paid caregiver] we have more of a social relationship than a caregiver relationship, which is nice. We can just go out to lunch or just visit for an hour or whatever and it is not ‘Did you take your medicine? You’re sure?’ because I was being the nag.” (#12 caregiver) | |

| “Now [caregiver] doesn’t have to worry about anything. With the schedule here, there are people who can watch me. Security knows where I am, when I go outside, so she can just go.” (#12 patient) |

Agreement about one another’s competency to perform disease management tasks

Patients were confident that their caregivers had adequate knowledge of their needs and could articulate those needs to healthcare providers. They trusted their caregivers with managing prescription medications; caregivers felt competent doing so. Supportive dyads also agreed about the patient’s (in) ability to perform health-related tasks (Table 1).

Mutual understanding

Patients attempted to reduce the demands on their caregiver by being “good patients” (#11) and adhering to their treatment regimens. Caregivers validated patients’ efforts and acknowledged the challenges associated with losing one’s physical function.

Collaborative decision-making and disease management

Supportive dyads worked together to make treatment decisions that were satisfactory to the patient and caregiver (Table 1). The caregiver wanted to make sure that the patient’s preferences for care were recognized, and the patient wanted to make sure that the caregiver’s needs were taken into account.

Use of family and formal caregiving

Although supportive dyads preferred family to formal caregiving, providing full-time assistance was not always possible. They discussed alternative solutions that would satisfy the needs of both dyad members, such as employing paid helpers and moving the patient to an assisted living facility (Table 1).

Conflicted Dyads

Disagreement about caregiver level of involvement

Patients felt that their caregivers’ involvement was excessive or inappropriate. In doctors’ visits, patients felt that, with the caregiver present, their own voice was not being heard. Caregivers felt that their involvement was necessary to impart accurate information when the patient lacked English-language skills or intentionally withheld information from the doctor (Table 2).

Table 2.

Themes Characterizing Conflicted Caregiving Relationships

| Disagreement about caregiver level of involvement | “[Caregiver] is the one who talks. She doesn’t let me talk. I’m the one I want to talk. I talk to the doctor about my stomach when I’m not feeling good, but now she’s the one who talks for me.” (#8 patient) |

| “I don’t let [patient] go alone to the doctor’s…. She doesn’t tell the doctor actually what she really feels. That’s why I stepped in. I want her to understand that, whatever she is feeling, let the doctor know, and when I tell the doctor she gets very upset because I am telling the doctor how she feels because he needs to know what is going on.” (#8 caregiver) | |

| “[Caregiver] is too much. He wants to do and answer all the questions. There is no way he can be me.” (#3 patient) | |

| “We have problems because English is not our mother language, and sometimes she gets stuck on things, and I know it.” (#3 caregiver) | |

| Disagreement about one another’s competency to perform disease-related tasks | “[Patient] is talking about her knee surgery. When she was [living] here for three weeks, I [organized] the medications.” (#14 caregiver) |

| “I can [manage them] myself. I would sit here and look what…” (#14 patient) | |

| “She wanted to make sure that I was putting the right pills in [the pill box]. I have the list here, but she wanted to sit here and check it.” (#14 caregiver) | |

| “I did not trust [the caregiver with] pouring the right medicine at the right time and the right days.” (#13 patient) | |

| “One of [patient’s] problems was when you go to the generics. One generic may be a blue pill and the same exact medication may be purple. [Patient] would get upset because there was a purple pill where he expected a blue pill so that led to the problem.” (#13 caregiver) | |

| Underappreciation | “[Caregiver] is trying to treat me as if I am not a whole person right now. I have problems with walking. I have problems with my strength, but [caregiver] feels that, by driving me [to physical therapy], all these things will fix themselves, and that is not the case.” (#13 patient) |

| “[Patient] says no one knows his pain. Well the same thing is true. He has no idea what kind of pain I am in or how fatigued I feel.” (#13 caregiver) | |

| Disagreement over decision-making and disease management | “The doctor doesn’t tell me how many times you have to [check the blood sugar]. Never. They just ask me how the sugar is; that’s it. I do it, but I’m not going to do it three or four times a day. I just do it in the morning, that’s it.” (#8 patient) |

| “But what [doctor] told me is that he wants it and that you should be taking it three times a day. One in the morning, one after you finish eating, and one before you go to bed…. We have disagreements, but she knows that she can’t get away with it because I am right here.” (#8 caregiver) | |

| “I am fighting a gang. [Caregiver], my daughter, and my son…. I was not left with any opportunity to make a decision. They had already called rehab. I didn’t really have any choice.” (#13 patient). | |

| “It was a question of we just didn’t trust you [to perform your exercise regimen at home].” (#13 caregiver) | |

| Use of formal caregiving | “[Caregiver] started to pour [the medications] and unfortunately, I did not trust her. So that is why the nurse is here: to prepour the medications.” (#13 patient) |

| “Patient would get very angry and very upset, so that is when I said we were going to turn [the medications] over to [the aide]. She is going to do it, and then there is no argument…. Now we have an aide who comes in around supper time and makes sure that he takes those pills and then his nighttime pills again…. I was tired of listening to his criticizing and his questioning. It was not worth having to put up with that.” (#13 caregiver) |

Disagreement about one another’s competency to perform disease management tasks

Patients did not trust their caregivers to administer medications; whereas caregivers felt equipped to perform this task. Caregivers were skeptical of patients’ ability to follow treatment regimens, manage medications, or communicate adequately with the doctor; patients felt competent to perform these activities without assistance (Table 2).

Underappreciation

Patients felt that caregivers had unrealistic expectations of patients’ ability to manage their health conditions. Caregivers described their role as “the mother of a toddler” (#13) or “unpaid slave” (#3), asserting that the patient did not fully recognize the stress associated with caregiving.

Disagreement over decision-making and disease management

Patients and caregivers disagreed over decisions about the patient’s healthcare (Table 2), including rehabilitation and day-to-day management of the patient’s health conditions (e.g., diet, exercise, number of blood draws, use of assistive devices).

Use of formal caregiving

Conflicted dyads employed formal caregivers, including home health aides, to alleviate tension within the dyad. Distrust within the relationship motivated their decision to employ paid helpers (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Older adults with multiple health conditions and their family caregivers described a common set of tasks for the management of their conditions. Although their preferences and attitudes toward the receipt and provision of these tasks were highly personal, the dyads sorted into 2 groups. Supportive dyads shared a mutual respect for one another’s experiences; conflicted dyads expressed feelings of underappreciation and held opposing perspectives on one another’s abilities to perform disease management tasks.

Studies of patients or caregivers of patients with specific diseases have documented a range of attitudes toward family caregiving. Patient attitudes have been described in a small number of studies examining specific clinical scenarios, including family involvement in mental health care,17 geriatric assessment,18 an invasive procedure,19 and after a hospitalization.10 Qualitative research has found that some caregivers of individuals with dementia derive a strong sense of meaning in giving back to their loved one, whereas others are resentful of their caregiving duties.20 This study builds on this prior research to explore attitudes toward caregiving in a broader population of older adults and their caregivers who face a variety of tasks to manage multiple conditions. It highlights the conflicts that can arise over caregiver involvement in these tasks and the reasons for these conflicts. Although the role of caregivers in older adults’ medical visits has received increasing attention,4,5,18,21 the current study points to a potential tension regarding caregiver involvement: patients reporting unwanted interjections by the caregiver during discussions with the doctor and caregivers arguing that their involvement is necessary to impart accurate information. It also provides novel insight into patient–caregiver interactions during disease management tasks that have received little attention from a dyadic perspective, including medication management, exercise for rehabilitation, and blood glucose monitoring. Some dyads harbored distrust of one another’s abilities or willingness to perform these tasks independently. Such conflicts are important for healthcare providers to be aware of as they interact with patients and caregivers in medical visits and design treatment plans that take into account the preferences and capabilities of both individuals.

This study highlights the benefit of using a dyadic approach to better understand caregiving relationships. Studies of adult child caregivers have shown that greater perceived disagreement among siblings about a parent’s health care can directly affect an individual’s caregiver stress,22,23 and research with marital dyads has shown that hostility in one spouse can negatively affect the other’s health and functioning.24,25 Rather than focusing on one family member’s experience, the dyadic approach used in the present study allowed confirmation of how patients and caregivers perceived their interactions. For example, conflicted dyads used language that reinforced their lack of shared understanding, with one patient commenting that he was fighting a gang (his family) and the caregiver (his wife) responding that she felt like the mother of a toddler. Further research is needed that explicitly examines conflict within patient–caregiver relationships as a potential risk factor for poor outcomes in addition to the well-known burdens of chronic disease and caregiving.

Although no dyads reported supportive and conflicted aspects of their relationships, evidence and theory from the psychological literature suggest that complex caregiving dynamics may exist.26,27 The absence of findings that illustrate a wider range of caregiving relationships may have resulted from the lack of interview probes that specifically target this issue. Alternatively, power dynamics within the dyad may have led individuals to converge on their views.

As a qualitative study, conclusions cannot be drawn regarding the prevalence of individuals’ preferences or attitudes. The non-random sampling method used to recruit study participants limits the generalizability of our findings, and the cross-sectional study design precludes the ability to examine how caregiving attitudes change over time.

Although individuals with multimorbidity and their family caregivers perform a universal set of disease management activities, their preferences for accepting or providing assistance with those activities are highly personal. Our findings support a dyadic approach to managing multiple health conditions that aligns patient preferences with caregiver involvement.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sharon Jennings and Maria Zenone for help with transcription. We also thank Yuliya Riat, Ronald Miller, Ann Datunashvili, Cynthia Gnecco, IwonaLlacka, John Dunlop, Kasia Lipska, and Jackie Curl for their help with recruitment.

Financial Disclosure: Terri Fried and Peter H. Van Ness are supported by the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale University School of Medicine (P30AG021342 National Institute on Aging). Catherine Riffin is supported by training Grant T32AG1934 from the National Institute on Aging.

Sponsor’s Role. No sponsor placed any restriction on this work or had any role in the design of the study; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; or preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no financial, personal, or potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Appendix S1:Patient and family caregiver interview guide.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gerteis J, Izrael D, Deitz D et al. Multiple Chronic Conditions Chartbook. AHRQ Publication No. Q14–0038. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freedman VA, Spillman BC. Disability and care needs among older Americans. Milbank Q 2014;92:509–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Families Caring for an Aging America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolff JL, Roter DL. Family presence in routine medical visits: A meta-analytical review. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:823–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolff J Family matters in health care delivery. JAMA 2012;308: 1529–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reinhard S, Levine C, Samis S. Home Alone: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Chronic Care. Washington, DC: AARP and United Hospital Fund; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson L, Hutchings D, Corner L et al. Balancing rights and risks: Conflicting perspectives in the management of wandering in dementia. Health Risk Soc 2007;9:389–406. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ekman SL, Norberg A. The autonomy of demented patients: Interviews with caregivers. J Med Ethics 1988;14:184–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landau R, Auslander GK, Werner S et al. Families’ and professional caregivers’ views of using advanced technology to track people with dementia. Qual Health Res 2010;20:409–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boutin-Foster C In spite of good intentions: Patients’ perspectives on problematic social support interactions. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2005; 3:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazzoni D, Cicognani E. Problematic social support from patients’ perspective: The case of systemic lupus erythematosus. Soc Work Health Care 2014; 53:435–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P et al. Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. Am T Psychiatry 1983;140: 734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. Newbery Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armstrong D, Gosling A, Weinman J et al. The place of inter-rater reliability in qualitative research: An empirical study. Sociology 1997;31:597–606. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Source-book, 2nd Ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen AN, Drapalski AL, Glynn SM et al. Preferences for family involvement in care among consumers with serious mental illness. Psych Serv 2013; 64:257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishikawa H, Roter DL, Yamazaki Y et al. Patients’ perceptions of visit companions’ helpfulness during Japanese geriatric medical visits. Patient Educ Couns 2006;61:80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eichhorn DJ, Meyers TA, Guzzetta CE et al. Family presence during invasive procedures and resuscitation: Hearing the voice of the patient. Am J Nurs 2001;101:48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shim B, Barroso J, Davis LL. A comparative qualitative analysis of stories of spousal caregivers of people with dementia: Negative, ambivalent, and positive experiences. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:220–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolff JL, Guan Y, Boyd CM et al. Examining the context and helpfulness of family companion contributions to older adults’ primary care visits. Patient Edu Couns 2017;100:487–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strawbridge WJ, Wallhagen MI. Impact of family conflict on adult child caregivers. Gerontologist 1991;31:770–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwak M, Ingersoll-Dayton B, Kim J. Family conflict from the perspective of adult child caregivers: The influence of gender. J Soc Pers Relatsh 2012;29: 470–487. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton TL. Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychol Bull 2001;127:472–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riffin C, Löckenhoff CE, Pillemer K et al. Care recipient agreeableness is associated with caregiver subjective physical health status. J Gerontol B Psychol Soc Sci 2012;68B:927–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark MS, Mills JR. A theory of communal (and exchange) relationships In: Van Lange PAM, Kruglanski AW, Higgins TE, eds. Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology. London: Sage Publications; 2012:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rook KS, Ituarte PHG. Social control, social support, and companionship in older adults’ family relationships and friendships. Pers Relationsh 2005;6: 199–211. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.