ABSTRACT

Background

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is an established risk factor for heart failure (HF) and is a component of the Framingham Heart Failure Risk Score (FHFRS). Whether LVH detected by electrocardiogram (ECG‐LVH) is equally predictive of HF as LVH detected by echocardiography (echo‐LVH) is unclear.

Hypothesis

ECG‐LVH and echo‐LVH are equally predictive of HF.

Methods

This analysis included 4543 participants (85% white; 41% male) age ≥65 years from the Cardiovascular Health Study who were free of HF at baseline. Incident HF was identified during a median follow‐up of 12 years. ECG‐LVH was defined by the Cornell criteria. Echo‐LVH was defined as left ventricular mass >95th percentile (male, >212 g; female, >175 g). Cox proportional hazard regression was used to examine the association between ECG‐LVH and echo‐LVH, separately with incident HF. Harrell's concordance C‐index was calculated for the FHFRS with inclusion of ECG‐LVH and echo‐LVH, separately.

Results

At baseline, 168 participants had ECG‐LVH and 226 had echo‐LVH. A total of 1380 incident HF events occurred during follow‐up. Both ECG‐LVH and echo‐LVH were predictive of incident HF (for ECG‐LVH, hazard ratio: 1.39, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.08‐1.77; for echo‐LVH, hazard ratio: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.22‐1.89). The ability of the FHFRS to predict HF was similar when ECG‐LVH (C‐index: 0.772, 95% CI: 0.726‐0.815) and echo‐LVH (C‐index: 0.772, 95% CI: 0.727‐0.814) were included into the model separately.

Conclusions

Both LVH‐ECG and echo‐LVH are equally predictive of incident HF and can be used interchangeably in HF risk‐prediction models.

Introduction

About 1 million heart failure (HF) hospitalizations occur in the United States each year.1 Effective prevention of this growing public health concern requires early detection of individuals at risk. The Framingham Heart Failure Risk Score (FHFRS) was developed to identify individuals at high risk for developing HF.2 One of the components of the FHFRS is left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH). Left ventricular hypertrophy can be assessed using electrocardiography (ECG‐LVH) or imaging such as echocardiography (echo‐LVH). Although ECG is easy to interpret, readily available, and inexpensive, it has been shown to have low sensitivity for detecting LVH.3, 4 Despite its low sensitivity, ECG‐LVH has been shown to predict incident HF.2, 5 It has recently been shown that there is a disconnect between the ability of ECG to detect LVH and its value as a predictor of outcomes.6 Whether ECG‐LVH is equally predictive of HF as echo‐LVH and whether the FHFRS predictive ability changes by change in the method of LVH detection are currently unclear. Therefore, the purpose of this analysis was to compare the ability of ECG‐LVH and echo‐LVH to predict HF, in isolation or as part of the FHFRS, in the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS).

Methods

Details of the CHS have been previously described.7 Briefly, CHS is a prospective population‐based cohort study of risk factors for coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke in individuals age ≥65 years. A total of 5888 participants with Medicare eligibility were recruited from 4 field centers in the United States: Forsyth County, North Carolina; Sacramento County, California; Washington County, Maryland; and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Participants were followed with semiannual contacts, alternating between telephone calls and surveillance clinic visits. The CHS clinic examinations ended in June 1999, and since then 2 yearly phone calls to participants were used to identify events and collect data. The institutional review board at each site approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from participants at enrollment. For the purpose of this analysis, we excluded participants with missing follow‐up, baseline HF, missing baseline covariate data, or with major ventricular conduction abnormalities, including complete left bundle branch block, that could impact the interpretation of ECG‐LVH criteria.

The ECG‐LVH was determined from the baseline ECG. Identical electrocardiographs (MAC PC; Marquette Electronics Inc., Milwaukee, WI) were used at all clinic sites, and resting, 10‐second standard simultaneous 12‐lead ECGs were recorded in all participants.8 ECG‐LVH was defined by the Cornell criteria (R‐wave amplitude aVL plus S‐wave amplitude V3 ≥ 28 mm for men and ≥20 mm for women).9

Echo‐LVH was determined from the baseline echocardiogram for each study participant according to previously described techniques.10 Measurements were made from digitized images using an offline image‐analysis system equipped with customized computer algorithms. Left ventricular (LV) mass was derived from standard formulas described by Devereux et al.11 Echo‐LVH was defined by LV mass values >95th sex‐specific percentiles (male, >212 g; female, >175 g).

Heart failure cases were identified by adjudication of medical records, including hospitalization data, as previously described.12, 13 Briefly, a self‐reported history of a physician diagnosis of HF was followed by review of participants' medical records. Heart failure was determined from both the physician diagnosis and/or treatment, defined by a current prescription for typical HF therapies (eg, diuretics, digitalis, and vasodilators). Additionally, typical symptoms, signs, and chest X‐ray findings of HF were reviewed by the CHS Events Committee. In this analysis, incident cases were defined as the first occurrence of probable or definite HF during follow‐up in participants who were free of HF at baseline.

Participant characteristics were collected during the initial CHS interview and questionnaire. Age, sex, race, income, and education were self‐reported. Smoking was defined as current or ever smoker. Total cholesterol, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C), plasma glucose, and high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (hs‐CRP) were measured from participants' blood samples that were obtained after a 12‐hour fast at the local field centers. Diabetes mellitus (DM) was defined as a self‐reported history of a physician diagnosis, a fasting glucose value ≥126 mg/dL, or by the current use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic medications. Blood pressure was measured for each participant in the seated position, and systolic measurements were used in this analysis. The use of aspirin, statins, and antihypertensive medications was self‐reported. Body mass index (BMI) was computed as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. Baseline CHD was determined by a self‐reported history or by review of the medical records.11

Categorical variables were reported as frequency and percentage, whereas continuous variables were recorded as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance for categorical variables was tested using the χ2 method and the Wilcoxon rank sum procedure for continuous variables. Comparisons were examined between participants with and without LVH by ECG and echocardiography separately. We examined the association between LVH at baseline with incident HF. Follow‐up time was defined as the time from the initial study examination until one of the following: HF, death, loss to follow‐up, or end of follow‐up, which was July 1, 2008. Kaplan‐Meier estimates were used to compute cumulative incidence of HF by LVH, and the differences in estimates were compared using the log‐rank procedure.14 Cox proportional hazards regression was used to compute hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association between ECG‐LVH and echo‐LVH, separately, with incident HF. Multivariable models were constructed as follows: model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and income; and model 2 adjusted for model 1 covariates plus smoking status, systolic blood pressure (SBP), DM, BMI, total cholesterol, HDL‐C, aspirin, statin, antihypertensive medications, log(hs‐CRP), CHD, and stroke.

We compared the predictive performance of the FHFRS when ECG or echocardiography is considered as the method defining LVH in the score. Specifically, using methodology developed for survival analyses,15 we computed Harrell's concordance index (C‐index) for models that included ECG‐LVH as originally done in the FHFRS and echo‐LVH, separately, plus the other components of the score (age, heart rate, SBP, BMI, DM, CHD, valve disease).2

The proportional hazards assumption was not violated in all of our analyses.16 Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

Of the 5888 participants from the original CHS cohort, we excluded 69 participants with missing follow‐up, 274 participants with baseline HF, 627 with missing baseline covariate data, and 375 with major ventricular conduction defects, including complete left bundle branch block. A total of 4543 participants (85% white; 41% male) with complete data remained and were included in this analysis. Of those with missing follow‐up, only 5 had ECG‐LVH and 8 had echo‐LVH. The prevalence of ECG‐LVH and echo‐LVH in those excluded is not statistically different from those in the main analysis.

ECG‐LVH was detected in 168 (3.7%) participants and echo‐LVH was present in 226 (5.0%) participants. A total of 59 cases of LVH were detected by both ECG and echocardiography. Baseline characteristics stratified by ECG‐LVH and echo‐LVH are shown in Table 1. Overall, participants with elevated SBP or using BP‐lowering drugs, higher BMI, DM, higher levels of CRP, or history of CHD were more likely to have LVH by both ECG and echo.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics (N = 4543)

| Characteristic | ECG‐LVH, n = 168 | No ECG‐LVH, n = 4375 | P Valuea | Echo‐LVH, n = 226 | No Echo LVHn = 4317 | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 0.044 | 0.20 | ||||

| 65–70 | 60 (36) | 1985 (45) | 117 (52) | 1928 (45) | ||

| 71–74 | 41 (24) | 1040 (24) | 47 (21) | 1034 (24) | ||

| 75–80 | 45 (27) | 956 (22) | 42 (19) | 959 (22) | ||

| >80 | 22 (13) | 94 (9) | 20 (9) | 396 (9) | ||

| Male sex | 46 (27) | 1801 (41) | 0.0004 | 93 (41) | 1754 (41) | 0.88 |

| White race | 121 (72) | 3761 (86) | <0.0001 | 126 (56) | 3756 (87) | <0.0001 |

| Education high school or less | 98 (58) | 2502 (57) | 0.77 | 148 (65) | 2452 (57) | 0.010 |

| Income < $25 000/year | 112 (67) | 2752 (63) | 0.32 | 163 (72) | 2701 (63) | 0.0037 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 27 (4) | 26 (4) | 0.030 | 32 (3.7) | 26 (4) | <0.0001 |

| Current or former smoker | 70 (42) | 2338 (53) | 0.0027 | 114 (50) | 2294 (53) | 0.43 |

| DM | 40 (24) | 643 (15) | 0.0012 | 74 (33) | 609 (14) | <0.0001 |

| Heart rate, bpm, mean (SD) | 69 (12) | 68 (11) | 0.53 | 69 (12) | 68 (11) | 0.29 |

| SBP, mm Hg, mean (SD) | 153 (24) | 139 (20) | <0.0001 | 148 (22) | 139 (20) | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 215 (39) | 213 (39) | 0.53 | 206 (37) | 213 (39) | 0.010 |

| HDL‐C, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 54 (16) | 55 (16) | 0.19 | 50 (14) | 55 (16) | <0.0001 |

| Medication use | ||||||

| Antihypertensives | 108 (64) | 1911 (44) | <0.0001 | 147 (65) | 1872 (43) | <0.0001 |

| Statin | 3 (2) | 104 (2) | 0.62 | 3 (1) | 104 (2) | 0.30 |

| Aspirin | 59 (35) | 1426 (33) | 0.49 | 79 (35) | 1406 (33) | 0.46 |

| Log(hs‐CRP), mg/L, mean (SD) | 1.2 (1) | 0.91 (1) | 0.0020 | 1.5 (1) | 0.88 (1) | <0.0001 |

| CHD | 37 (22) | 642 (15) | 0.0087 | 56 (25) | 623 (14) | <0.0001 |

| Valve disease | 12 (7) | 221 (5) | 0.23 | 15 (7) | 218 (5) | 0.29 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECG‐LVH, electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy; echo‐LVH, echocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; hs‐CRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation.

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Statistical significance for continuous data was tested using Wilcoxon rank sum procedure and categorical data was tested using the χ2 test.

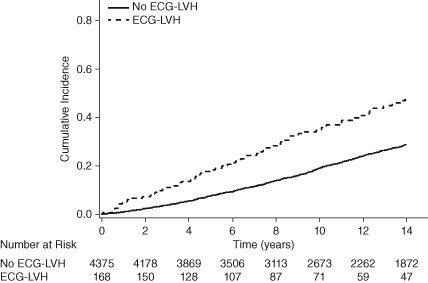

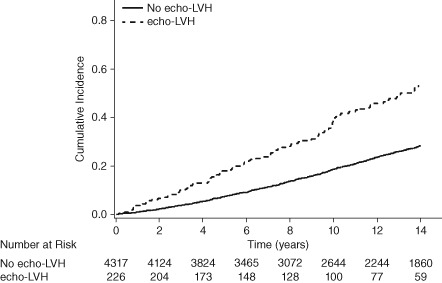

Over a median follow‐up of 12.2 years (interquartile range, 7.1–17.9 years), a total of 1380 participants developed incident HF. The incidence rate of HF was higher in participants with ECG‐LVH and echo‐LVH compared with those without (P < 0.001; Table 2). The unadjusted cumulative incidence of HF by ECG‐LVH status and echo‐LVH status (log‐rank P < 0.0001 for both) are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively.

Table 2.

Risk of HF by LVH Status (N = 4543)

| Events/No. at Risk | Incidence Rate per 1000 Person‐years (95% CI) | Model 1, HRa (95% CI) | P Value | Model 2, HRb (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No ECG‐LVH | 1311/4375 | 24.8 (23.5‐26.2) | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — |

| ECG‐LVH present | 69/168 | 43.2 (34.1‐54.7) | 1.80 (1.41‐2.30) | <0.0001 | 1.39 (1.08‐1.77) | 0.0097 |

| No LVH | 1271/4317 | 24.3 (23.0‐25.7) | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — |

| Echo‐LVH present | 109/226 | 51.5 (42.7‐62.2) | 2.26 (1.85‐2.78) | <0.0001 | 1.52 (1.22‐1.89) | 0.0002 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECG‐LVH, electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy; echo‐LVH, echocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; hs‐CRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and income.

Adjusted for Model 1 covariates plus smoking status, SBP, DM, BMI, total cholesterol, HDL‐C, aspirin, statins, antihypertensive medications, log(hs‐CRP), and CHD.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of HF by ECG‐LVH. Abbreviations: ECG‐LVH, electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy; HF, heart failure.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of HF by echo‐LVH. Abbreviations: echo‐LVH, echocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy; HF, heart failure.

In a multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis, both ECG‐LVH and echo‐LVH were associated with increased risk of HF, with echo‐LVH being slightly more predictive of HF than ECG‐LVH (Table 2). Nevertheless, the overall ability of FHFRS to predict HF was exactly the same whether ECG‐LVH or echo‐LVH was included in the model (C‐index: 0.772 for both; Table 3).

Table 3.

Harrell's C‐index for Framingham Model for Incident HFa

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | C‐index (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECG‐LVH | 1.32 (1.03‐1.69) | 0.026 | 0.772 (0.726‐0.815) |

| Echo‐LVH | 1.49 (1.21‐1.85) | 0.0002 | 0.772 (0.727‐0.815) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECG‐LVH, electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy; echo‐LVH, echocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Adjusted for the components of the Framingham HF Risk Score (age, heart rate, SBP, BMI, DM, CHD, valve disease).

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that LVH, whether detected by electrocardiogram (ECG‐LVH) or echocardiography (echo‐LVH), is associated with increased risk of incident HF. Although ECG is known to have low sensitivity to detect LVH, our study shows that it is equally predictive of HF as echocardiography. This means that ECG‐LVH and echo‐LVH can be used interchangeably in HF risk‐prediction models.

Our findings suggest that the prognostic value of ECG‐LVH is more than what can be explained by anatomical changes of the left ventricle. This concept has been suggested by several recent studies,6, 17 which calls for a paradigm shift in the thinking of ECG‐LVH as a predictor of outcome rather than a measure of LV mass.

ECG‐LVH and echo‐LVH detect different conditions. The QRS changes that occur with ECG‐LVH have been shown to represent a combination of anatomic and electric remodeling.18, 19 In contrast, echo‐LVH commonly relies entirely on LV mass.20 Although differences exist in what cardiac pathology each method actually detects, equally important prognostic information is obtained from both ECG‐LVH and echo‐LVH. The implication for this to the clinicians assessing HF risk is that the combination of clinically relevant risk factors and data from the standard 12‐lead ECG is able to provide valuable prognostic information regarding HF risk, even without relying on costly imaging modalities.

Heart failure affects nearly 7 million Americans, and by the year 2030 its prevalence will increase by 25%.1, 21 Heart failure disproportionately affects older individuals, and with the projected growth in the number Americans age >65 years, the health care system will experience significant financial strain.22 Cost‐effective efforts to identify individuals who are at high risk for HF and the development of targeted preventive programs to reduce this risk are needed. This is highlighted in the current analysis, as we have shown that LVH by the inexpensive ECG method has equal prognostic ability compared with echo‐LVH to predict HF when included in clinically relevant prediction models.

Study Limitations

Our results should be interpreted in the context of certain limitations. We defined ECG‐LVH by the Cornell criteria only, although there are many other LVH criteria. Nevertheless, Cornell criteria are considered among the most commonly used LVH criteria and physicians are very familiar with them compared with others. We defined echo‐LVH by 95th‐percentile cutoff values based on LV mass. Other definitions for echo‐LVH have been proposed, and the results may vary with alternative definitions. However, in additional analysis (results not shown), we defined echo‐LVH as LV mass index values >1.45 based on sex‐specific predicted LV mass that have been previously derived in the CHS,23 and the results were the same. Also, the generalizability of our results maybe limited because the CHS cohort consists predominantly of elderly Caucasians. Further studies might be needed to verify the same results in other minority groups. Finally, the C‐statistic is considered fairly insensitive to change, even when clinically significant differences in likelihood ratio for different predictors are present. Thus, the justification for the “interchangeability” between ECG‐LVH and echo‐LVH for outcomes prediction may be based on a metric that is unlikely to show any change even if meaningful differences were present. However, the purpose of using C‐statistics in our analysis was to determine if the model performance remains similar when using either ECG‐LVH or echo‐LVH, not how much the model improves by using LVH in general. In this context, using a highly sensitive or less sensitive tool should not impact the ability to compare model performance with ECG‐LVH and echo‐LVH, because the tool would impact the models' performance in a similar way, keeping the relative differences between the models constant.

Conclusion

Both LVH‐ECG and echo‐LVH are equally predictive of incident HF and can be used interchangeably in HF risk‐prediction models.

This article was prepared using Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) Research Materials obtained from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the CHS or the NHLBI.

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd‐Jones DM, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association [published correction appears in Circulation. 2012;125:e1002]. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kannel WB, D'Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, et al. Profile for estimating risk of heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1197–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aronow WS, Ahn C, Kronzon I, et al. Congestive heart failure, coronary events and atherothrombotic brain infarction in elderly blacks and whites with systemic hypertension and with and without echocardiographic and electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Cardiol. 1991;67:295–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jain A, Tandri H, Dalal D, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic utility of electrocardiography for left ventricular hypertrophy defined by magnetic resonance imaging in relationship to ethnicity: the Multi‐ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am Heart J. 2010;159:652–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gottdiener JS, Arnold AM, Aurigemma GP, et al. Predictors of congestive heart failure in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1628–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bacharova L, Chen H, Estes EH, et al. Determinants of discrepancies in detection and comparison of the prognostic significance of left ventricular hypertrophy by electrocardiogram and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:515–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1:263–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Furberg CD, Manolio TA, Psaty BM, et al; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group). Major electrocardiographic abnormalities in persons aged 65 years and older (the Cardiovascular Health Study). Am J Cardiol. 1992;69:1329–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Devereux RB, Casale PN, Eisenberg RR, et al. Electrocardiographic detection of left ventricular hypertrophy using echocardiographic determination of left ventricular mass as the reference standard: comparison of standard criteria, computer diagnosis and physician interpretation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1984;3:82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gardin JM, Wong ND, Bommer W, et al. Echocardiographic design of a multicenter investigation of free‐living elderly subjects: the Cardiovascular Health Study [published correction appears in J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1992;5:550]. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1992;5:63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Lutas EM, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: comparison to necropsy findings. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57:450–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Bild D, et al. Methods of assessing prevalent cardiovascular disease in the cardiovascular health study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:270–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ives DG, Fitzpatrick AL, Bild DE, et al. Surveillance and ascertainment of cardiovascular events: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:278–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gray RJ, Tsiatis AA. A linear rank test for use when the main interest is in differences in cure rates. Biometrics. 1989;45:899–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harrell FE Jr, Califf RM, Pryor DB, et al. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. JAMA. 1982;247:2543–2546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grambsch P, Therneau T. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515–526. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chrispin J, Jain A, Soliman EZ, et al. Association of electrocardiographic and imaging surrogates of left ventricular hypertrophy with incident atrial fibrillation: MESA (Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2007–2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bacharova L, Estes EH, Bang LE, et al. Second statement of the Working Group on Electrocardiographic Diagnosis of Left Ventricular Hypertrophy. J Electrocardiol. 2011;44:568–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bacharova L, Szathmary V, Kovalcik M, et al. Effect of changes in left ventricular anatomy and conduction velocity on the qrs voltage and morphology in left ventricular hypertrophy: a model study. J Electrocardiol. 2010;43:200–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bacharova L, Szathmary V, Potse M, et al. Computer simulation of ECG manifestations of left ventricular electrical remodeling. J Electrocardiol. 2012;45:630–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al; for American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee ; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Stroke Council. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:606–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Odden MC, Coxson PG, Moran A, et al. The impact of the aging population on coronary heart disease in the United States. Am J Med. 2011;124:827e5–833.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gardin, JM , Siscovick D, Anton‐Culver H, et al. Sex, age, and disease affect echocardiographic left ventricular mass and systolic function in the free‐living elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation. 1995;91:1739–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]