ABSTRACT

Canadian Indigenous populations are disproportionately affected by rising rates of diet-related chronic disease and have been experiencing rapid lifestyle changes affecting diet. In recognition of these issues, this study aimed to obtain greater understanding of attitudes and meanings around healthy eating in a semi-remote community in Eeyou Istchee. A qualitative study design used semi-structured interviews and observational field notes to explore local accounts of food and health. Two distinct versions of “healthy eating” were identified: one relating to traditional food and preparation methods; the other reflecting medicalised accounts of illness and diagnosed conditions. The latter links with “southern” modes of accessing and preparing food, demonstrating local capacity to adapt to the rapid changes in body, lifestyle and environment being experienced. New connections, associating non-native ways with traditional practices, are being formed where traditional ways of living on the land have been severed. These local accounts show how people are continually negotiating different constructs of “healthy eating.” These findings expand current understandings of the context of food and healthy eating in Eeyou Istchee, emphasising present-day and historical experiences of the land. Future research and diet-related health interventions must continue to acknowledge and incorporate local understandings of health to help address the broader socio-political factors that shape Indigenous lifestyles, environments and health.

KEYWORDS: Indigenous population, healthy diet, traditional diet, chronic disease, public health, social ecological model

Introduction

Diet-related chronic diseases are of increasing international concern. Diabetes, for example, has a global prevalence of 8.5%, almost double that of 30 years ago [1]. Most diagnoses are type II diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which may be treated with a healthy diet [1]. Indigenous populations are disproportionately affected by T2DM [2,3]. Contributing diet and lifestyle factors are exacerbated by rapid lifestyle change and marginalisation, characterised as disruption of social and cultural norms and loss of traditional ways of life [3,4]. This paper explores, through a socio-environmental perspective, perceptions of food and diet in a semi-remote Indigenous community in Canada.

Over 150 years of oppressive Canadian policy have resulted in significant changes to Indigenous ways of life, including traditional food-gathering practices, and health [5,6]. Indigenous peoples continue to experience challenging conditions such as contaminated drinking water [7,8], serious lack of proper housing [7], restricted health-care access [9], and high food insecurity [6,10,11]. Prevalence of overweight in Indigenous communities has been linked with rates of T2DM and other chronic diseases, often above non-Indigenous rates [4,12]. Experiences of health in Indigenous communities have been shown to be associated with experiences of colonialism, structural racism, and poverty [3–5,13].

With rapid lifestyle westernisation, Indigenous diets are increasingly of high caloric and low nutritional value [14–16]. Accelerated change in eating practices with limited healthier options has been linked with chronic disease [3,16,17]. Contributing factors include reduced nomadic hunter-gatherer activity and increased use of motorised vehicles in hunting, exacerbating the rise of a sedentary lifestyle; food insecurity; and lack of fresh food in stores [3,15,16]. Despite nutrition transition, communities place importance on consuming and passing on knowledge about traditional food [6,18]. The context of food and healthy nutrition is complex and multi-faceted.

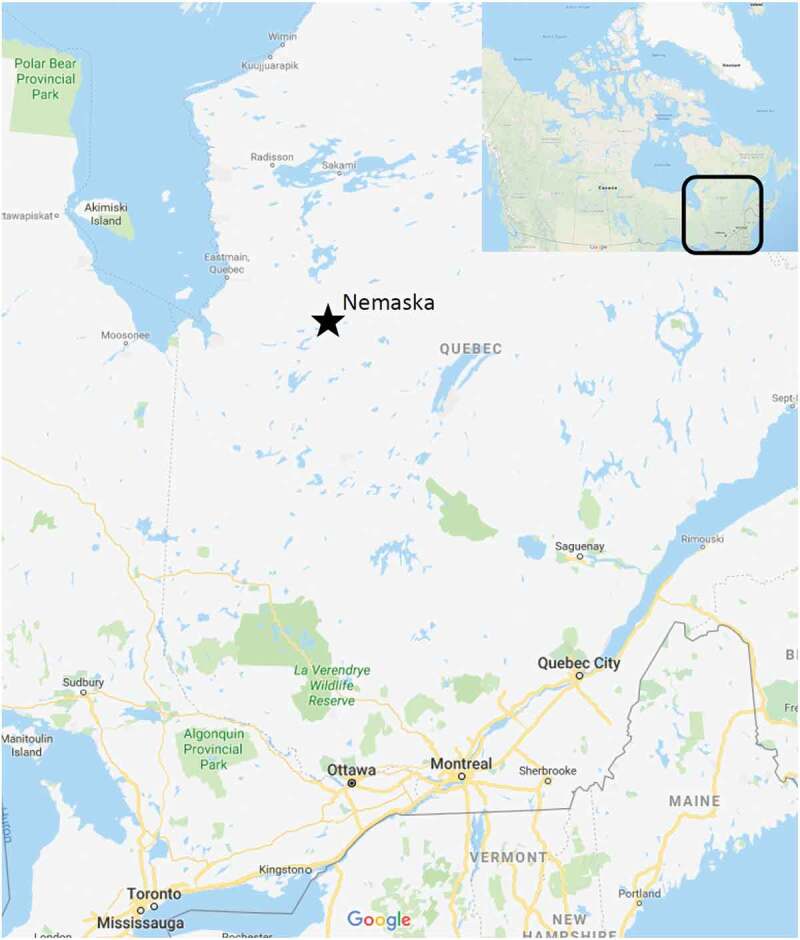

This study focuses on experiences of food, diet, and health in Nemaska, a small Cree community with 851 inhabitants on Champion Lake in central Eeyou Istchee, north-eastern Quebec (Figure 1) [19,20]. Biomedical perspectives frame overweight and T2DM as “problems” in First Nation communities, and a growing body of Canadian literature acknowledges that more critical perspectives examine food and eating alongside colonial history, constrained opportunities and resources, and environmental issues, such as fish mercury levels [4,19–21]. Previous research identified variation in health across Indigenous communities resulting from historically different colonial interactions with governments [13] and gaps in Indigenous health research with respect to “nutritious food” [22]. Lack of research understanding of cultural meanings attached to health and wellbeing in Eeyou Istchee [15] is allied by a continued need to adopt a community-sensitive approach to Indigenous health research [13,17,23]. Examining perceptions of food and diet in Nemaska will contribute to a broader picture of the range of influences on and experiences of diet-related health among Indigenous populations facing disproportionate risks of diet-related chronic disease.

Figure 1.

Map identifying the location of Nemaska (Map data ©2019 Google)

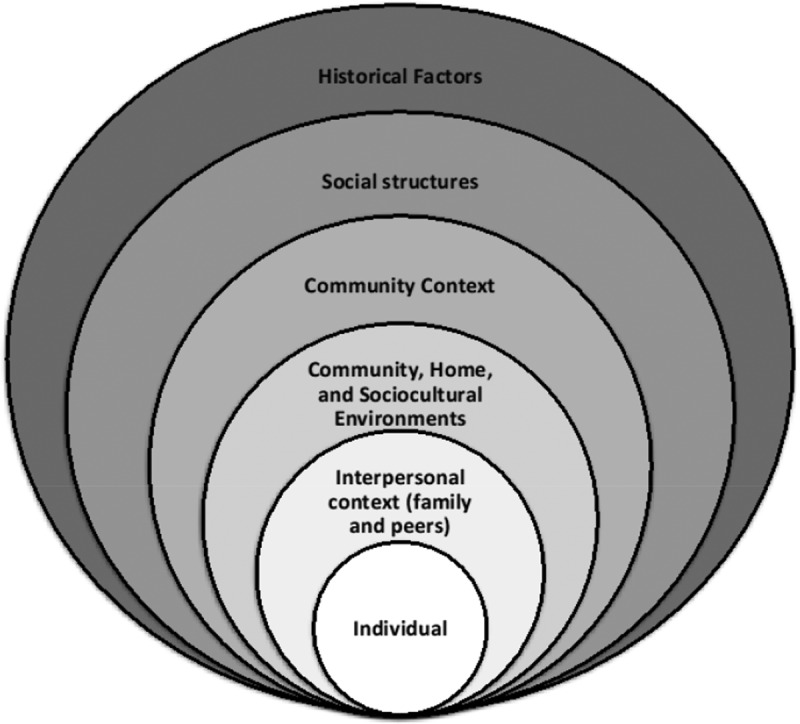

In considering the complexity of different factors shaping food, diet and health, a socio-ecological model (SEM) was used to facilitate exploration of the interconnectedness of individuals and their environments [21,24]. Literature investigating obesity in Eeyou Istchee recommends SEM for examining influences of collective factors on eating practices as it foregrounds the intersection of individual behaviour and environment [15,19,21].

Methods

Study overview

This study was conducted June–July 2017 in Nemaska, Canada (Figure 1). A qualitative study design enabled exploration of knowledge [25,26] of community members as key informants [27]. Semi-structured interviews, informed by observation, facilitated understanding the community context, consistent with precedent set in previous research [13,15,18,26]. Ethical approval was granted by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, contingent on local approval, given by Nemaska’s Chief.

Recruitment and methods

To recruit key informants for interviews, EG connected with community members through an existing contact and attending local events, reflecting convenience sampling. The interview topic guide was created to explore individual experiences, attitudes, and practices regarding food, based on an adapted SEM from Laberge-Gaudin [15] and Willows [21] (Figure 2). SEM informed the development of the focus and broader domains of the topic guide, but the questions were not limited to SEM dimensions.

Figure 2.

An adapted socio-ecological model helped shape the topic guide

Eight interviews (45 min to 1.5 h) were conducted in English with a range of key informants. The interviews were held in places of informants’ choosing – at home or during daily activities, such as driving – to help build rapport. Informants were given participant information sheets to read before consenting to be interviewed. Interviews were audio-recorded with informant consent and transcribed verbatim. Pseudonyms were given to maintain anonymity. EG kept reflexive field notes throughout the fieldwork period, jotting observations and questions for the interviews and to guide analysis.

Analysis

Thematic analysis of the transcripts involved a deductive process using themes identified from the literature and SEM model to develop an initial coding framework. Multiple close readings of the data line-by-line were then performed to identify additional themes in a more inductive approach. These were combined to develop over-arching analytical narratives.

Findings

Contextual background (Figure 1)

In an informal conversation with EG, the chief gave a history of the community, helping situate informants’ accounts of diets and constructions of meaning around food. Nemaska – Cree: “namess” (fish) and “ka” (many) – was established as an important gathering place from pre-settler times, and, today, is the seat of the Grand Council of the Crees and the Cree Regional Authority. The Cree Nation of Nemaska has experienced recent extensive lifestyle shifts, no longer depending on fur-trade, the bush, and hunting for livelihood. In the 1960s, the Québec government negotiated flooding of their ancestral home, Old Nemaska, for a hydroelectric project. This camp, on the Rupert River, is where people of Nemaska (Nemaska Eenouch) gathered during summer months to fish. The community had a church, a trading post, a dry goods store, and a school. Winters were spent on family trap lines in the bush. In 1970, residents were forced to disperse, mostly relocating to the closest communities of Misstissini and Waskaganish. Ultimately, Old Nemaska was not flooded. People were prevented in rebuilding due to the remote access. Old Nemaska is, even now, accessible only by boat. Champion Lake was designated the Cree Nation of Nemaska reserve. Today most people live in town and return to the bush for periods of time. Many Nemaska Eenouch have rebuilt their cabins in Old Nemaska for holiday use. The site remains much as it was without electricity, running water or telephone reception. The Old Nemaska Gathering in July is an important time when much of the town moves there for 2 weeks, and traditions, especially regarding food, are cherished and passed on.

Across Eeyou Istchee, significant changes in lifestyle are reflected in changes in health and how people relate to food [14,28]. Interview analysis yielded four overarching themes: “Constructing meaning around food,” “Making sense of change,” “Connectedness,” and “The body.” Underlying these themes was a complex conceptualisation of “healthy eating,” in which local “traditional” views of health mixed with external “southern” ones.

Constructing meaning around food

Informants’ accounts of food could be roughly categorised into “traditional,” “store food,” and fruit and vegetables from the store. “Traditional food,” harvested “from the land,” included bush/“wild” meat, fish, and berries. “Store food” was used synonymously with “unhealthy”/“junk” food, but also indicated imported food from “down south.” When informants spoke of healthy and/or store food, certain “fruit and vegetables” appeared to be conceptualised separately.

During interviews, the process of obtaining food surfaced as inherent to the meaning of healthy food. At the time of the study, the grocery store was stocked once a week. A young mother, Ruth, related having to “wait for fruit and vegetables to come in.” Residents described needing to be aware of the best times to get groceries, as well as having time to go.

Informants described store food in two ways: one expressing discontent regarding available options –

Most of the food is boring […] they don’t know how to choose the right food for the people. (Gloria)

And another condemning it as negatively impacting people’s health –

Comparing now what we eat […] from the store […] you’re killing the body. (Solomon)

When asked to define healthy food, six participants cited traditional foods without hesitation. Frequent unprompted references to traditional food as “healthy” further evidenced this belief. Yet, as interviews unfolded, definitions became more flexible, expanding to include preparation and ingredients. Diana referenced “southern” cooking methods for preparing food:

Sautéing it or stir-fry […] when you prepare something, you’re putting all your love into that – like when I’m cooking for my family, I’m making sure, you know, that they’re eating something right.

As in this quote, informants discussed how food preparation, whether traditional or non-traditional, is important for healthy meals. Aimée said “anything can be made healthy, just by the way you cook it.”. Informants tended to refer to “traditional food” (especially older participants and those with access to hunting activities) and to food “made from scratch” (those who lived outside the reserve in urban settings) when speaking about “healthy food.” They spoke of preferring “fresh” ingredients, using “olive oil” or “coconut oil” instead of “Crisco oil” or “Tenderflake” for cooking, and mentioned cooking from “down south” or “conventional” cooking.

Making sense of change

The blurring of traditional and non-traditional food definitions shows how people are integrating different views of healthy eating. Descriptions of using non-traditional cooking methods with traditional food (“moose stir fry”) highlights an interesting phenomenon of “making sense of change”, wherein people are developing ways of adapting to cultural and social changes. That certain fruit and vegetables, not part of traditional diets, were talked about separately from store food and as “healthy” is an indicator of this process.

Informants compared their experiences with other communities and, especially, with “down south.” Clara, a health worker, spoke of a desire for difference, describing an active process of adaptation and change:

They travel so much to Val d’Or or down south, that they see other food and novelty and things, that’s what they would like.

Many participants alluded to the past – how the way they cook and eat has changed – referring to differences in diet arising from changes in the availability of food. Aimée explained the difference between the time of her grandparents and attitudes today with reference to food scarcity in earlier times:

[Today] they overeat – sometimes they say, ‘I’m eating healthy,’ but they overeat. It’s not like they’re starving anymore … like back in the day […] they didn’t have food.

Others portrayed past Cree “bodies” as “strong and healthy,” due to the connection to the land, unlike today’s bodies which have become sick, “weak and un-resistant.” Traditional foods were described as offering healing techniques alongside, or instead of, biomedicine. One informant described eating moose liver to increase his blood cell count, instead his prescribed iron pills, after having lost much blood.

“Keeping the identity” was an important concern for health, requiring adaptation to change so that “young people” would be interested in learning the traditions. In a deeply impactful moment, an informant spoke of how “real Cree” is being lost, overtaken by the influence of other cultures.

Out there on the land […] the history comes to me, the voices from the Elders talk to me – the way they did it, I have to do it … but when you live in […] Nemaska, you don’t have that kind of thinking […] it kills them […] they don’t have what I have … the words from the mother earth […] we are dying as a Cree nation … we have to go back to the land to be a real Indian. Today we’re not real Indians […] If we go back, we’re gonna be healthy … understand? (Solomon)

Solomon is expressing a poignant feeling that EG encountered repeatedly during fieldwork – a sense that their ancestors lived healthy lives, and that, with the loss of their culture, their health is in decline. Informants framed culture loss especially as loss of their ways of living on the land and being forcefully relocated from their traditional home. Life is no longer shaped by the need to be geared towards survival in the bush and informants perceived the rapid social and cultural change as affecting their health.

Connectedness

Part of “making sense of change” was the idea of connectedness. Feelings of disconnection and interconnection were voiced by informants, particularly when speaking of traditions, the land, and residential school. Many described a deep “connection that we have with the land” and indicated that this was severed over time, impacting the community’s health. Solomon told a story about speaking “from the land,” from the perspectives of the fish and the river, and in defence of it during recent Rupert River Diversion negotiations. He highlighted how life and health are interconnected with different factors and the importance of maintaining and protecting those connections. He emphasised that people start to get sick when these connections are broken. Diana agreed:

It’s all interconnected. We’re all interconnected in one way or another […] my grandfather would say, it’s all like a spider web. And he said, all the animals work that way eh – all creation works that way […] he was talking about the river at that time […] once LaGrande is affected, everything in creation is affected, he said. Even us […] we’re supposed to protect them.

A moving expression of disconnection was recounted by Ruth who expressed feeling helpless in her inability to pass on traditional cooking to her children. She told how her mother, like many others, had gone to residential school and her grandmother was therefore unable to pass on traditional food preparation knowledge. Diana identified a similar disconnection from the land and cultural identity due to residential schooling, and linked this to the rise in obesity:

Disconnecting our roots completely […] already happened once when our parents were taken away to residential school […] when they came back, they had to carry that intergenerational trauma […] that’s where obesity really started.

The body

“The body” emerged as a major theme during analysis, despite there being no questions about embodied health in the topic guide. Informants discussed how they related to and were aware of their body and its needs, caring for it and managing its health, often in relation to eating “healthy.” Diana described a deciding moment that gave her motivation for dietary change. Her husband had been away working, so she “didn’t see him for two months and he came back […] even my kids were like, ‘oh my G*d, Dad really grew, like Dad grew this way’ [indicates increased girth].”

Many informants described how traditional food affected their bodies, making them feel “fuller longer,” filled with “positive energy,” and “strong”; going without makes them “feel sick.” Store food “kills” and makes Cree bodies “weak and unresistant.” Ruth and Mary spoke of their blood “sugar levels” and noticing them normalise after eating traditional foods, further affirming traditional food as “more healthy.”

An interesting notion of personal responsibility towards health emerged. Diana stated, “I told [husband] if you love yourself a little more, you wouldn’t buy that crap.” Women with children or grandchildren tended to give an account of being unable to care for themselves. Being “in a rush” was mentioned frequently, as were lack of energy, feeling tired, and needing “an easy way.” They spoke of observing others taking care of their health the way they would for themselves. In Ruth’s account of being diagnosed with T2DM, denial and a very busy lifestyle came together to make her feel, “I didn’t take care of myself.”

Accounts of non-compliance indicated resistance to medical recommendations. Sally, who has T2DM, told of her struggle to eat as the clinic advised. She finds herself eating the food she should not – “pasta is no good […] I eat it, ‘cause I have to cook it for the children.” Informants overall expressed feelings of ambivalence towards managing their health conditions as advised. Mary said she often feels like eating what clinic staff told her not to eat. Ruth said, “I don’t like checking my sugar cause the numbers are too high” and expressed fear of fainting if she were to follow the doctor’s recommendation to exercise.

The four identified themes indicate two constructions of “healthy eating”: a local concept, relating to traditional access, food, and preparation methods; and an imported concept, relating to what people pick up from biomedicine with respect to illness and diagnosed health conditions. The latter could be linked with “southern” modes of accessing and preparing food, which indicate a capacity to adapt to the rapid change being experienced by the “Cree body”. New connections, linking non-native ways with traditional practices are being formed where old ones, traditional ways of living on the land, have been severed.

Discussion

This paper explored local meanings of traditional and non-traditional foods and healthy eating in Nemaska. Informants conceptualised healthy food in similar ways, suggesting that health is closely associated with traditional food and practice. Healthy food is defined by tradition, preparation process, and ingredients used. Feelings of connection/disconnection played a large role in how informants related to and explained their health, especially regarding being “on the land” and past residential school experiences. Narratives of making sense of change and conceptualisations of the body were prominent in many accounts. While there is a body of public health research on T2DM prevention and management in Indigenous communities [2,3,23], this has often been positioned in isolation from research on food and food practices among these populations [18,29]. Findings from this study contribute to bridging the two in showing how people relate to food and what healthy eating means to them, uncovering some of the tensions between traditional and conventional [18] ideas of healthy eating.

This study found that current perceptions of food and eating practices are interconnected with historical experiences of the land, evidenced by references to Elders and their ways and historical events. Previous work, emphasising the importance of community-level health research, argued that different colonial experiences and the resulting cultural impacts should be examined carefully as key determinants of Indigenous health [13,15]. Informants repeatedly raised traditional activities and being connected with the land, describing how low access to land meant less access to traditional activities, hindering them in obtaining traditional foods. Informants described themselves as unable to make the most out of the potential around them with respect to their health. Past forced relocation and negotiations over access to traditional hunting grounds likely influenced informants’ current experiences and perceptions of food and healthy eating. This is vital knowledge for understanding the most appropriate ways to support access to food and better health within this population.

The SEM-supported notion of connections between people, contemporary living and environment, including the accessing and preparing of food this study identified, highlights “the interconnectedness of things” [26]. The interconnection goes beyond usual interpretations of SEM, which focus on current social and environmental factors, and brings historical experiences to the fore. While SEM is valuable in understanding a range of health determinants in Indigenous communities, a historical dimension is also needed, and must be considered when designing public health approaches to addressing diet-related health conditions. Wilson and Rosenberg recommend a discerning approach towards cultural determinants of health, avoiding homogenizing categorization [30]. They asserted the need to include more measures of traditional practices when exploring Indigenous health [30]. Further consideration is needed of how broader cultural, historical and political experiences constitute the “Cree body” in relation to food, diet and related health.

People in Nemaska are continually negotiating different constructs of “healthy eating,” which are sometimes in tension and reflect broader experiences of rapid change. Analysis shows how they are adapting to rapid change in lifestyle and health – how they are combining traditional practices with “new knowledge” and how perceptions of food and healthy eating are changing as a result. “Interconnected influences” affect traditional food consumption in light of significant and rapid lifestyle changes [15]. These seem to include language and “Cree identity,” which link with perceptions of health. Cree identity is described as involving traditional practices around being on “the land” and hunting/traditional meats, which depend on family/friend relationships and/or access to the land. These directly relate to someone’s access to hunters or ability to hunt and determine access to traditional meats and thus relate to perceived health. Research in other Eeyou Istchee communities argued that “efforts to promote and maintain traditional food consumption could improve the overall health and wellbeing of Cree communities” [15]. Public health approaches to addressing diet-related illness should seek to find ways to acknowledge and accommodate the tension between different constructs of healthy eating. Willows [21] emphasises dispossession of traditional land as an important factor for Indigenous populations health. In the context of rapid change, collaboration between health and broader policy approaches would support and protect Indigenous access to land to facilitate the continuation of traditional practices (perceived as a fundamental to good health in this community).

Limitations

The small-scale qualitative study design means that transferability of interpretations to other Indigenous contexts must be done with caution. However, the key themes’ comparability with research in other Indigenous communities in Canada suggests a broader salience of the ideas around the connectedness of food and health in contexts of historical and current change. Limited time and use of convenience sampling by [author 1] resulted in most participants being women which restricted consideration of gendered aspects of accessing food and healthy eating. A lack of funds meant that interviews were not conducted in Cree, which may have limited some of the richness of informants’ accounts. Another possible study limitation relates to the position of the researcher conducting the interviews [author 1] as a non-native “outsider.” However, the outsider status likely enabled access to accounts that might not have been shared with someone assumed to have a shared knowledge of the community and context. That being said, the authors come from a Euro-American public health perspective, which meant that the research was conducted and interpreted primarily within a Euro-American framework. Recognizing the limitations in the given context, the authors recommend taking a more participatory, community-led approach in to help ensure Indigenous frameworks and ways of knowing are inherent in future research [31].

Conclusion

This study highlights interconnectedness of food, diet, health and broader experiences of change and the past, thus expanding public health understandings of what “healthy eating” might mean in Eeyou Istchee beyond biomedical dimensions. The multiple constructions of “healthy”, in relation to food, must be accommodated in public health initiatives to address the higher rates of diet-related disease faced by this community. Health research must continue to consider local conceptions of and relations to food and health to help guide efforts mitigating effects of rapid westernisation of Indigenous lifestyle and changes in environment. Furthermore, health interventions should reflect both the historical and contemporary contextual dynamics in which food-related behaviours are situated and shaped. Acknowledging that this study has been conducted from a western biomedically informed public health perspective, future research should be conducted from a participatory perspective and reflecting Indigenous epistemologies. Within this framing, it would be valuable to explore embodied engagements with food practices and health, and how these might be shaped by gender roles, to generate deeper understanding of the complex dynamics of social, political and environmental factors shaping Indigenous experiences of food and health.

Data availability statement

The anonymised interview transcripts are in encrypted storage and available until 2022 (5 years after the study was completed). Please contact the first author for further details.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].World Health Organization Diabetes Fact Sheet. 2018. [cited 2019 March08]. Available from: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes

- [2].Dyck R, Osgood N, Lin TH, et al. Epidemiology of diabetes mellitus among First Nations and non-First Nations adults. CMAJ. 2010;182(3):249–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Leung L. Diabetes mellitus and the aboriginal diabetic initiative in Canada: an update review. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016;5(2):259–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Frohlich KL, Ross N, Richmond C.. Health disparities in Canada today: some evidence and a theoretical framework. Health Policy. 2006;79(2–3):132–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Truth and reconciliation commission of Canada: calls to action. Winnipeg; 2015. Available from: http://nctr.ca/reports.php [Google Scholar]

- [6].Skinner KH, Hanning RM, Desjardins E, et al. Giving voice to food insecurity in a remote indigenous community in subarctic Ontario, Canada: traditional ways, ways to cope, ways forward. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Canada: Country Summary: Human Rights Watch 2017. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2017/country-chapters/canada

- [8].Bradford LEA, Bharadwaj LA, Okpalauwaekwe U, et al. Drinking water quality in Indigenous communities in Canada and health outcomes: a scoping review. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2016;75:32336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Oosterveer TM, Young TK. Primary health care accessibility challenges in remote indigenous communities in Canada’s North. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015;74 DOI: 10.3402/ijch.v74.29576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Aboriginal food security in Northern Canada: an assessment of the state of knowledge. 2014. Available from: https://scienceadvice.ca/reports/aboriginal-food-security-in-northern-canada-an-assessment-of-the-state-of-knowledge/

- [11].Tarasuk V, Mitchell A, Dachner N. Household food insecurity in Canada, 2014 [Internet]. Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF). Toronto: PROOF: Food Insecurity Policy Research; 2017. Available from: https://proof.utoronto.ca/resources/proof-annual-reports/annual-report-2014/ [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gionet LR, Roshanafshar S. Health at a glance: select health indicators of First Nations people living off reserve, Métis and Inuit. Catalogue no. 82-624-X2015 Health Statistics Division: Statistics Canada; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jacklin K. Diversity within: deconstructing aboriginal community health in Wikwemikong Unceded Indian Reserve. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(5):980–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Johnson-Down LM, Egeland GM. How is nutrition transition affecting dietary adequacy in Eeyouch (Cree) adults of Northern Quebec, Canada? Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2013;38(3):300–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Laberge-Gaudin V, Receveur O, Walz L, et al. A mixed methods inquiry into the determinants of traditional food consumption among three Cree communities of Eeyou Istchee from an ecological perspective. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2014;73 DOI: 10.3402/ijch.v73.24918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Akande VO, Hendriks AM, Ruiter RA, et al. Determinants of dietary behaviour and physical activity among Canadian Inuit: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Martin DH. “Now we got lots to eat and they’re telling us not to eat it”: understanding changes to south-east Labrador Inuit relationships to food. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2011;70(4):384–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Elliott B, Jayatilaka D, Brown C, et al. “We are not being heard”: aboriginal perspectives on traditional foods access and food security. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:130945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Nituuchischaayihtitaau Aschii Multi-community Environment-and-health Study in Eeyou Istchee, 2005–2009: final Technical Report. In: Nieboer E, Robinson E, editors. Public Health Report, Series 4 on the Health of the Population Cree Board of Health and Social Services of James Bay; 2013. September 20–21, 51–52.

- [20].Cree Board of Health and Social Services Annual report of the Cree Board of Health and Social Services of James Bay, 2017–2018. In: Morrow K, editor. Chisasibi; 2018. 9, 24 Available from: http://www.creehealth.org/annual-reports [Google Scholar]

- [21].Willows ND, Hanley AJG, Delormier T. A socioecological framework to understand weight-related issues in aboriginal children in Canada. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37(1):1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Willows ND. Determinants of healthy eating in aboriginal peoples in Canada: the current state of knowledge and research gaps. Can J Public Health. 2005;96:S32–S36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rice K, Te Hiwi B, Zwarenstein M, et al. Best practices for the prevention and management of diabetes and obesity-related chronic disease among indigenous peoples in Canada: a review. Can J Diabetes. 2016;40(3):216–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nutland W, Cragg LN. Health promotion practice. 2nd ed. Berkshire, England: McGraw Hill Education, Open University Press; 2015. p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Green JT, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research (introducing qualitative methods series). 3rd ed. London, UK: Sage Publications Ltd; 2014. p. 6,33,94. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nielsen MO, Gould LA. Non-Native scholars doing research in Native American communities: A matter of respect. Social Sci J. 2007;44(3):420–433. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hayward MN, Paquette-Warren J, Harris SB, Forge Ahead Programme Team . Developing community-driven quality improvement initiatives to enhance chronic disease care in Indigenous communities in Canada: the FORGE AHEAD program protocol. Health Res Policy Syst. 2016;14:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Khalil CB, Johnson-Down L, Egeland GM. Emerging obesity and dietary habits among James Bay Cree youth. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(11):1829–1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Proust F, Johnson-Down L, Berthiaume L, et al. Fatty acid composition of birds and game hunted by the Eastern James Bay Cree people of Quebec. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2016;75:30583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wilson K, Rosenberg MW. Exploring the determinants of health for First Nations peoples in Canada: can existing frameworks accommodate traditional activities? Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(11):2017–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Smith LT. Decolonizing methodologies: research and Indigenous peoples. 2nd ed. London, UK: Zed Books; 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- World Health Organization Diabetes Fact Sheet. 2018. [cited 2019 March08]. Available from: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes

Data Availability Statement

The anonymised interview transcripts are in encrypted storage and available until 2022 (5 years after the study was completed). Please contact the first author for further details.