Abstract

Background

The worsening of serum creatinine (sCr) level is a frequent finding among ST‐segment elevation MI (STEMI) patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), associated with adverse short‐term and long‐term outcomes. No information is present, however, regarding the incidence and prognostic implications associated with an improvement in sCr levels throughout hospitalization, as compared with admission levels.

Hypothesis

Reversible renal impairment prior to PCI is not associated with adverse outcomes.

Methods

We retrospectively studied 1260 STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI. The incidence of in‐hospital complications and long‐term mortality was compared between patients having stable, worsened (>0.3 mg/dL increase), or improved (>0.3 mg/dL decrease) sCr levels throughout hospitalization.

Results

Overall, 127 patients (10%) had worsening in sCr levels, whereas 44 (3.5%) had an improvement of sCr compared with admission levels. Patients with worsening sCR had more complications during hospitalization, higher 30‐day (13% vs 1%; P < 0.001) and up to 5‐year all‐cause mortality (28% vs 5%; P < 0.001) compared with those with stable sCR. No significant difference was found regarding complications and mortality between patients having an improvement in sCr and stable sCr. Compared with patients with stable sCr, the adjusted hazard ratio for all‐cause mortality in patients with worsened sCr was 6.68 (95% confidence interval: 2.1‐21.6, P = 0.002).

Conclusions

In STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI, renal impairment prior to PCI is a frequent finding. In contrast to post‐PCI sCr worsening, this entity is not associated with adverse short‐term and long‐term outcomes.

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) frequently complicates the course of acute ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and is associated with adverse outcomes.1, 2, 3, 4 The worsening of renal function throughout hospitalization in STEMI patients is multifactorial, though the most important reason is considered contrast‐induced nephropathy, related mainly to the amount of contrast material and to preprocedural renal function.5, 6, 7 Additional important reasons include hemodynamic state, drugs admitted (especially blockers of the renin‐angiotensin axis), as well as the occurrence of sepsis, bleeding, atheroembolic disease, and acute hyperglycemia.8, 9, 10 Although all trials assessing AKI among STEMI patients defined this complication on the basis of the rise of serum creatinine (sCr) during hospitalization compared with admission sCr levels,1, 2, 3, 4, 11, 12 no trial to date has examined the presence of rapid reversal of renal impairment present at hospital admission, prior to PCI, and its prognostic effect among STEMI patients. In the present study, we compared the incidence, in‐hospital complications, as well as the short‐term and long‐term mortality associated with sCr change patterns in a large cohort of consecutive STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI.

Methods

Study Population

We performed a retrospective, single‐center observational study at the Tel‐Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, a tertiary referral hospital with a 24/7 primary PCI service, including all 1367 consecutive patients admitted between January 2008 and July 2013 to the cardiac intensive care unit with the diagnosis of acute STEMI. Excluded were 28 patients who were treated either conservatively or with thrombolysis and 63 patients whose final diagnosis on discharge was other than anterior‐wall STEMI (eg, myocarditis or takotsubo cardiomyopathy). Also excluded were patients who died within 24 hours of admission (n = 12), because they would not have had sufficient time to develop post‐PCI AKI, and patients requiring chronic peritoneal or hemodialysis treatment (n = 4). The final study population included 1260 patients whose baseline demographics, cardiovascular history, clinical risk factors, treatment characteristics, and laboratory results were retrieved from their medical files.

Protocol

The diagnosis of STEMI was established by a typical history of chest pain, diagnostic electrocardiographic changes, and serial elevation of serum cardiac biomarkers.13 Blood samples were drawn during admission of all patients. Primary PCI was performed in patients with symptoms ≤12 hours in duration, as well as in patients with symptoms lasting 12 to 24 hours in duration if the symptoms continued to persist at the time of admission. Patient records were evaluated for in‐hospital mortality and complications occurring during the hospitalization. These included cardiogenic shock or the need for intra‐aortic balloon counterpulsation treatment, need for emergent coronary artery bypass graft surgery, mechanical ventilation or heart failure episodes treated conservatively, clinically significant tachyarrhythmias, bradyarrhythmias requiring pacemaker, as well as major bleeding (requiring blood transfusion). Mortality was assessed over a median period of 1526 ± 298 days (range, 2–2130 days) up to August 1, 2013. Assessment of survival following hospital discharge was determined from computerized records of the population registry bureau. The study protocol was approved by the local institutional ethics committee.

Laboratory Parameters

The sCr was determined upon hospital admission and at least once a day during the cardiac intensive care unit stay and was available for all analyzed patients. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was estimated using the abbreviated Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation.14 Baseline renal insufficiency was categorized as an eGFR ≤60 mL/min/1.73 m2.15 Patients were stratified into 3 groups according their sCr change patterns, compared with sCr levels at hospital admission, using the Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) criteria16: stable sCr (<0.3 mg/dL change), worsened sCr (defined as an increase in sCr >0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours of admission), and improved sCr (defined as both sCr >1.2 mg/dL upon hospital admission and concomitant decrease of >0.3 mg/dL in sCr within 48 hours). When available, sCr upon hospital discharge was compared with follow‐up sCr in patients with AKI. Renal function recovery was defined as maintained sCr levels (>30 days) compared with the hospital discharge levels.

Statistical Analysis

All data were summarized and displayed as mean ± standard deviation or median (25%–75%) for continuous variables and as number of patients (%) in each group for categorical variables. The P values for the χ2 square test were calculated with the Fisher exact test. Continuous variables were compared using the independent sample t test or Mann–Whitney test. The identification of the independent predictors of AKI was assessed using logistic regression. The influence of sCr change on the occurrence of all‐cause mortality was evaluated using multivariate Cox regression, adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, left ventricular ejection fraction, eGFR, baseline hemoglobin, white blood cell count, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (hs‐CRP), and AKIN status. A 2‐tailed P value of <0.05 was considered significant for all analyses. All analyses were performed with SPSS version 21 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

A total of 1260 STEMI patients treated by primary PCI were enrolled in the study, 294 (23%) of whom had baseline renal insufficiency upon hospital admission. A total of 127 patients (10%) had worsening of sCr, whereas 44 patients (3.5%) had an improvement in sCr. Only 2 (1%) patients among those developing AKI required renal‐replacement therapy throughout hospitalization; both had worsened sCr following PCI.

The baseline clinical characteristics of patients with stable, improved, and worsened sCr are listed in Table 1. With the exception of diabetes mellitus and admission hs‐CRP levels, no significant differences were present between patients with stable and improved sCr. On the other hand, patients with worsened sCr were more likely to be older and female and to have more comorbidities, longer symptom duration prior to emergency room admission, advanced coronary artery disease, higher hs‐CRP, lower left ventricular ejection fraction, and longer time until hospital discharge.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 1260 STEMI Patients According to sCR Change Pattern

| Variable | sCR Stable, n = 1089 | sCR Improved, n = 44 | P Value | sCr Worsened, n = 127 | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 60 ± 12 | 64 ± 14 | 0.05 | 72 ± 12 | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 891 (82) | 34 (77) | 0.43 | 88 (69) | 0.003 |

| DM | 211 (19) | 15 (34) | 0.02 | 39 (31) | 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 502 (46) | 23 (52) | 0.44 | 69 (54) | 0.167 |

| Hypertension | 441 (41) | 22 (50) | 0.21 | 91 (72) | <0.001 |

| Smoking history | 568 (52) | 20 (45) | 0.44 | 43 (34) | <0.001 |

| Family history of CAD | 183 (17) | 7 (16) | 0.99 | 8 (6) | 0.009 |

| Prior MI | 103 (9) | 2 (4) | 0.42 | 14 (11) | 0.49 |

| No. of narrowed coronary arteries | |||||

| 1 | 489 (45) | 15 (34) | 0.49 | 46 (36) | 0.07 |

| 2 | 327 (30) | 17 (39) | 0.47 | 34 (27) | 0.07 |

| 3 | 268 (25) | 12 (27) | 0.26 | 47 (37) | 0.003 |

| Time to ED, min | 374 ± 659 | 420 ± 808 | 0.39 | 528 ± 577 | <0.001 |

| D2B time, min | 44 ± 40 | 44 ± 19 | 0.87 | 45 ± 19 | 0.24 |

| Contrast material amount, mLb | 149 ± 18 | 134 ± 17 | 0.359 | 128 ± 52 | 0.06 |

| Admission eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 73 ± 17 | 50 ± 14 | <0.001 | 55 ± 20 | <0.001 |

| Admission sCr, mg/dL | 1.11 ± 0.19 | 1.60 ± 0.40 | <0.001 | 1.34 ± 0.44 | <0.001 |

| Peak sCr, mg/dL | 1.14 ± 0.20 | 1.60 ± 0.40 | <0.001 | 2.08 ± 0.97 | <0.001 |

| sCr change in hospital, mg/dL | 0.03 ± 0.17 | −0.40 ± 0.15 | <0.001 | 0.65 ± 0.69 | <0.001 |

| sCr at discharge, mg/dL | 1.07 ± 0.17 | 1.19 ± 0.30 | 0.007 | 1.64 ± 0.77 | <0.001 |

| Duration of hospitalization, d | 5.3 ± 2.9 | 7.0 ± 5.7 | 0.11 | 9.4 ± 7.6 | <0.001 |

| Peak CPK, U/L | 1180 ± 1384 | 1053 ± 1135 | 0.84 | 1231 ± 1438 | 0.93 |

| Admission CRP, mg/dL | 11.3 ± 25.3 | 29.7 ± 54 | 0.008 | 25.8 ± 43.8 | <0.001 |

| LVEF, % | 48 ± 8 | 48 ± 11 | 0.70 | 43 ± 9 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; CRP, C‐reactive protein; D2B, door‐to‐balloon; DM, diabetes mellitus; ED, emergency department; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; sCR, serum creatinine; SD, standard deviation.

Data are presented as mean ± SD or n (%).

P value for worsened sCR vs stable sCr.

Information on contrast volume amount was present for only 418 patients.

The worsening of sCr following STEMI resulted in more complications and adverse events during hospitalization, as well as higher 30‐day mortality. Those findings, however, were not found in patients with improved sCr (Table 2). Follow‐up sCr was available in 33 of 44 of patients with improved sCr, with 30 of 33 patients demonstrating maintained recovery of renal function.

Table 2.

In‐hospital Complications of 1260 STEMI Patients According sCr Change Pattern

| Variable | sCr Stable, n = 1089 | sCr Improved, n = 44 | P Value | sCr Worsened, n = 127 | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiogenic shock/need for IABC | 26 (3) | 2 (4) | 0.29 | 21 (17) | <0.001 |

| In‐hospital CABG | 13 (1) | 2 (4) | 0.11 | 9 (7) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 24 (2) | 2 (4) | 0.26 | 25 (20) | <0.001 |

| HF | 64 (6) | 1 (2) | 0.51 | 39 (31) | <0.001 |

| Severe bradycardia/cardiac pacemaker | 22 (2) | 6 (14) | <0.001 | 9 (7) | <0.001 |

| VF/tachycardia | 50 (5) | 5 (11) | 0.06 | 14 (11) | 0.002 |

| AF | 26 (2) | 3 (7) | 0.1 | 19 (15) | <0.001 |

| Major bleeding/blood transfusion | 13 (1) | 2 (4) | 0.11 | 12 (9) | <0.001 |

| 30‐day mortality | 11 (1) | 2 (4) | 0.09 | 16 (13) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; HF, heart failure; IABC, intra‐aortic balloon counterpulsation; sCr, serum creatinine; STEMI, ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction; VF, ventricular fibrillation.

Data are presented as n (%).

P value for worsened sCr vs stable sCr.

Long‐term Outcome

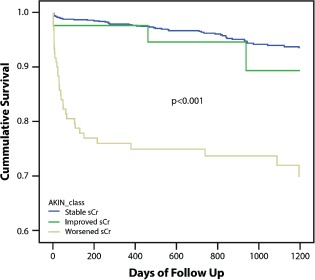

Over a mean period of 1526 ± 298 days (range, 2–2130 days), 95 (7.5%) patients of the entire cohort died. Mortality was significantly higher among those with worsening of sCr post‐PCI AKI (35 of 127, 28%) following STEMI than those with stable sCr (55 of 1089, 5.1%; P < 0.001) and those with improved sCr (5 of 44, 11%; P < 0.001; Figure 1). In multivariate analysis, worsening of sCr was an independent predictor of mortality, reaching a hazard ratio of 6.2 (95% confidence interval: 2.2‐17.3; P < 0.001), compared with patients with stable sCr. Improved sCr was not associated with increased risk for long‐term mortality (hazard ratio: 0.17, 95% confidence interval: 0.008‐3.4, P = 0.24).

Figure 1.

Cumulative survival rates for 1260 patients with STEMI on the basis of sCr changes throughout hospitalization (P < 0.001 for patients with stable sCr or improved sCr vs worsened sCr). Abbreviations: AKIN, Acute Kidney Injury Network; sCR, serum creatinine; STEMI, ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Discussion

This is the first study comparing the patterns of sCr changes among STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI and their relation to the angiographic procedure and coronary intervention. We found that unlike post‐PCI AKI, rapid reversal of AKI present upon hospital admission is a less frequent complication and has no major adverse effects on short‐term and long‐term outcomes. Moreover, the majority of patients with an improvement of sCr had maintained recovery of their renal function over a 30‐day follow‐up period.

Contrast material is still considered the major reason for AKI development in STEMI patients following PCI. Contrast‐induced acute kidney injury (CI‐AKI) is a prevalent and deleterious complication of coronary angiography and reported to be the third most common cause of hospital‐acquired renal failure.5 The risk of CI‐AKI is directly associated with increasing contrast‐media volume,6 with incidence ranging from 2% among patients with normal baseline renal function to as high as 20% to 30% in patients with a chronic renal failure.17 Even after adjusting for baseline renal function and comorbidities, in‐hospital mortality is about 5‐fold higher in CI‐AKI patients, and long‐term mortality rates are about 4‐fold higher.7 It is important to state that in our report patients developing post‐PCI AKI received less contrast material during PCI, probably due to the elevated sCr levels found upon admission in that group. This finding and the demonstration of renal impairment prior to PCI and contrast injection implies that other factors aside from CI‐AKI contribute to AKI development in the early setting of STEMI. The sudden myocardial insult in STEMI often results in an acute reduction of cardiac output, and this early hemodynamic deterioration may theoretically lead to reduced renal perfusion and early worsening of renal function. Short‐term renal hypoperfusion is often associated with a prerenal failure, defined as a reversible loss of renal function without structural damage.18 A more profound and prolonged hypoperfusion primarily affects the function and structure of tubular epithelial cells, which, in severe cases, is characterized by epithelial‐cell ischemia and necrosis.

In accordance with a previous report by our group,1 patients developing post‐PCI AKI had longer symptom duration, probably resulting in worse left ventricular function, with prolonged impairment of hemodynamics and renal perfusion. Symptom duration is a powerful prognostic marker in STEMI patients undergoing reperfusion,19, 20 and major consideration is given to minimizing ischemic duration to improve survival following STEMI.21 Longer ischemia duration is associated with more extensive and possibly irreversible myocardial damage,22 resulting in longer renal hypoperfusion, which may convert early prerenal insult into a renal (tubular or glomerular) injury.

There are currently only limited reports regarding the timing of the renal insult and its relation to clinical outcome. Kim et al reported that transient and persistent moderate/severe AKI during acute myocardial infarction is strongly related to 1‐year all‐cause mortality after STEMI.23 An additional study evaluated the impact of transient and persistent acute kidney injury on long‐term outcomes after STEMI,24 revealing that even transient AKI in these patients portends increased long‐term mortality and that patients with persistent AKI are in the highest risk group. Those studies defined transient AKI as transient worsening and improvement of sCr throughout hospitalization, as compared with admission sCr levels, and primary PCI was not applied to all patients. Contrary to these reports, we defined the improved sCr group as a continuous and persistent decline compared with admission levels, as was reported by Tian et al.25 Their results demonstrated that an increase in sCr level during hospitalization predicted worse outcomes, even if the sCr value returns to normal, whereas patients who presented to the hospital with an increased sCr level that returned rapidly to normal had outcomes approaching those of patients with sCr levels consistently in the normal range. We believe that the elevated sCr on admission with improving AKI represents an early, reversible hemodynamic‐induced kidney injury or, alternatively, changes in nonrenal Cr kinetics (eg, Cr production during illness).

Our findings carry some important clinical implications. As we have shown, the baseline sCr value early after admission for STEMI may not reflect the true baseline sCr, especially if it is mild and no history of risk factors or prior renal failure is present. The utilization of novel markers of tubular injury such as urinary/plasma neutrophil gelatinase‐associated lipocalin, urinary kidney injury molecule‐1, and urinary interleukin‐1826, 27 offer the opportunity to diagnose AKI proactively and may help to differentiate those in whom mild sCr represents an acute response rather than a chronic finding, allowing early interventions for renal protection.

Study Limitations

Our study bears some limitations. Data regarding the amount of fluids given to patients were absent in the majority of patients; thus, their possible effect on renal function recovery could not be determined. Similarly, concomitant therapy data with statins, renin‐angiotensin blockers, and diuretics throughout hospitalization were not present for many patients, and their effect on AKI development could not be assessed.

Although the AKI definition using the AKIN criteria16 refers to a sCr increase compared with the baseline value, the sCr at hospital admission, as we demonstrated, may not represent a true baseline value in STEMI patients, and follow‐up sCr was not available for most patients with no AKI. Finally, the definition of AKIN refers to sCr change within a time frame of 48 hours. As the change in sCr can lag beyond this time period due to delayed effects of contrast material and drugs, worsening of renal function might have occurred following hospital discharge in some patients; thus, the true incidence of AKI described in our study may have been an underestimation. Finally, as retrospective data regarding baseline renal function were not available for most of the present cohort, it is not possible to exclude that those having only transient elevation of sCr were more likely to have normal function at baseline compared with those with worsened sCr.

Conclusion

The worsening of renal function prior to PCI in STEMI patients is a frequent finding. In contrast to the well‐described post‐PCI AKI, this entity is often completely reversible and not associated with adverse short‐term and long‐term outcomes.

All authors take responsibility for all aspects of the reliability and freedom from bias of the data presented and their discussed interpretation.

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Shacham Y, Leshem‐Rubinow E, Steinvil A, et al. Renal impairment according to Acute Kidney Injury Network criteria among ST‐elevation myocardial infarction patients undergoing primary percutaneous intervention: a retrospective observational study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2014;103:525–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goldberg A, Hammerman H, Petcherski S, et al. Inhospital and 1‐year mortality of patients who develop worsening renal function following acute ST‐elevation myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2005;150:330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Parikh CR, Coca SG, Wang Y, et al. Long‐term prognosis of acute kidney injury after acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:987–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amin AP, Spertus JA, Reid KJ, et al. The prognostic importance of worsening renal function during an acute myocardial infarction on long‐term mortality. Am Heart J. 2010;160:1065–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. James MT, Ghali WA, Knudtson ML, et al. Associations between acute kidney injury and cardiovascular and renal outcomes after coronary angiography. Circulation. 2011;123:409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gurm HS, Dixon SR, Smith DE, et al. Renal function–based contrast dosing to define safe limits of radiographic contrast media in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:907–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seeliger E, Sendeski M, Rihal CS, et al. Contrast‐induced kidney injury: mechanisms, risk factors, and prevention. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2007–2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Koreny M, Karth GD, Geppert A, et al. Prognosis of patients who develop acute renal failure during the first 24 hours of cardiogenic shock after myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2002;112:115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marenzi G, Assanelli E, Campodonico J, et al. Contrast volume during primary percutaneous coronary intervention and subsequent contrast‐induced nephropathy and mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marenzi G, De Metrio M, Rubino M, et al. Acute hyperglycemia and contrast‐induced nephropathy in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2010;160:1170–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hwang SH, Jeong MH, Ahmed K, et al. Different clinical outcomes of acute kidney injury according to Acute Kidney Injury Network criteria in patients between ST‐elevation and non–ST‐elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2011;150:99–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marenzi G, Cabiati A, Bertoli SV, et al. Incidence and relevance of acute kidney injury in patients hospitalized with acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:816–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;61:e78–e140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, et al; Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Kidney Foundation (NKF) Kidney Disease Outcome Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) Advisory Board . K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S1–S266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levin A, Warnock DG, Mehta RL, et al; Acute Kidney Injury Network Working Group. Improving outcomes from acute kidney injury: report of an initiative. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tehrani S, Laing C, Yellon DM, et al. Contrast‐induced acute kidney injury following PCI. Eur J Clin Invest. 2013;43:483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Devarajan P. Update on mechanisms of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1503–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Newby LK, Rutsch WR, Califf RM, et al; GUSTO‐1 Investigators. Time from symptom onset to treatment and outcomes after thrombolytic therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1646–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cannon CP, Gibson CM, Lambrew CT, et al. Relationship of symptom‐onset‐to‐balloon time and door‐to‐balloon time with mortality in patients undergoing angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000;283:2941–2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bradley EH, Nallamothu BK, Herrin JT, et al. National efforts to improve door‐to‐balloon time: results from the Door‐to‐Balloon Alliance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2423–2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reimer KA, Lowe JE, Rasmussen MM, et al. The wavefront phenomenon of ischemic cell death. 1. Myocardial infarct size vs duration of coronary occlusion in dogs. Circulation. 1977;56:786–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim MJ, Choi HS, Oh SH, et al. Rapid reversal of acute kidney injury and hospital outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. Yonsei Med J. 2011;52:603–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goldberg A, Kogan E, Hammerman H, et al. The impact of transient and persistent acute kidney injury on long‐term outcomes after acute myocardial infarction. Kidney Int. 2009;76:900–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tian J, Barrantes F, Amoateng‐Adjepong Y, et al. Rapid reversal of acute kidney injury and hospital outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:974–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Coca SG, Yalavarthy R, Concato J, et al. Biomarkers for the diagnosis and risk stratification of acute kidney injury: a systematic review. Kidney Int. 2008;73:1008–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koyner JL, Parikh CR. Clinical utility of biomarkers of AKI in cardiac surgery and critical illness. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:1034–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]