ABSTRACT

Background

The increased mortality related to female gender in ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) has been reported from various patient cohorts and treatment strategies with controversial results. In the present work, we evaluated the impact of female gender on mortality and in‐hospital complications among a specific subset of consecutive STEMI patients managed solely by PPCI.

Hypothesis

Female gender is not an independent predicor for mortality among STEMI patients.

Methods

We performed a retrospective, single‐center observational study that included 1346 consecutive STEMI patients undergoing PPCI, of which 1075 (80%) were male. Patient's records were evaluated for 30‐day mortality, in‐hospital complications, and long‐term mortality over a mean period of 2.7 ± 1.6 years.

Results

Compared with males, females were older (69 ± 13 vs 60 ± 13 years, P < 0.001), had a significantly higher rate of baseline risk factors, and had prolonged symptom duration (460 ± 815 minutes vs 367 ± 596 minutes, P = 0.03). Females suffered from more in‐hospital complications and had higher 30‐day mortality (5% vs 2%, P = 0.008) as well as higher overall mortality (12.5% vs 6%, P < 0.001). In spite of the significant mortality risk in unadjusted models, a multivariate adjusted Cox regression model did not demonstrate that female gender was an independent predictor for mortality among STEMI patients.

Conclusions

Among patients with STEMI treated by PPCI, female gender is associated with a higher 30‐day mortality and complications rates compared to males. Following multivariate analysis, female gender was not a significant predictor of long‐term death following STEMI.

Introduction

Early reports from the era of thrombolysis demonstrated that females diagnosed with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) had an increased risk of mortality and post–myocardial infarction (MI) adverse events as compared to males.1, 2, 3, 4 This increased risk has been mainly explained by the difference in baseline risk profiles, but also by the longer time needed for diagnosis, which led to longer time to reperfusion and less aggressive and/or invasive treatments.5, 6, 7 In the current primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) era, various studies support to the notion that gender by itself does not independently predict death following STEMI.5, 8, 9, 10 However, most of the previous reports that have evaluated the association of gender with patients' outcomes have included patients from the entire spectrum of the acute coronary syndromes who were managed by various treatment strategies.5, 9, 11

The association of gender with patient outcomes merits investigation in specific patient subsets being treated by the current guidelines‐driven practice.12 In the present analysis we evaluated the association of gender with short and long‐term mortality as well as with in‐hospital complications following STEMI in a large cohort of consecutive STEMI patients who were all treated by PPCI.

Methods

Study Population

We performed a retrospective, single‐center observational study at the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, a tertiary referral hospital with a 24/7 primary PCI service. Included were all 1404 consecutive patients admitted between January 2008 and December 2013 to the cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) with the diagnosis of acute STEMI. Excluded were 21 patients who were treated either conservatively or with thrombolysis, and 37 patients whose final diagnosis on discharge was other than STEMI (eg, myocarditis in 25 patients or Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in 12 patients). The final study population included 1346 patients whose baseline demographic, cardiovascular history, clinical risk factors, treatment characteristics, and laboratory results were retrieved from their medical files.

The diagnosis of STEMI was established by a typical history of chest pain, electrocardiographic changes, and serial elevation of serum cardiac biomarkers.12 PPCI was performed in patients with symptoms ≤ 12 hours in duration as well as in patients with symptoms lasting 12 to 24 hours in duration if the symptoms continued to persist at the time of admission. Following admission to the CICU, treatment with β‐blockers, statins, and renin/angiotensin blockers were started in all patients unless contraindicated. Left ventricular ejection fraction was measured in all patients, by bedside echocardiography, within the first 48 hours of admission. Patient records were evaluated for in‐hospital mortality and complications occurring during the hospitalization. These included acute renal failure, cardiogenic shock, or the need for intra‐aortic balloon counterpulsation treatment, need for emergent coronary artery bypass graft surgery, mechanical ventilation or heart failure episodes treated conservatively, clinically significant tachyarrhythmias (ventricular fibrillation, sustained ventricular tachycardia, and atrial fibrillation), and bradyarrhythmias requiring pacemaker and major bleeding (requiring blood transfusion). Mortality was assessed over a period of 5 years up to August 1, 2013. Assessment of survival following hospital discharge was determined from computerized records of the population registry bureau. The study protocol was approved by the local institutional ethics committee.

Statistical Analysis

All data were summarized and displayed as mean (± standard deviation) for continuous variables and as a number (percentage) of patients in each group for categorical variables. Continuous and categorical variables were analyzed using the independent sample t test and the Pearson χ2 test, respectively.

The Kaplan‐Meier and log‐rank test were used to evaluate the unadjusted effect of gender on patient survival. Logistic regression and multivariate adjusted Cox proportional hazard models were fitted for mortality as the dependent variable and adjusted to variables found significant in the univariate models. A 2‐tailed P value of < 0.05 was considered significant for all analyses. All analyses were performed with the SPSS 20.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

The study population included 1346 patients with mean age 62 ± 13 years (range, 25–96 years), of which 1075 (80%) were males. Demographic, clinical, angiographic, and laboratory findings of the patient population are presented in Table 1. Compared with males, female patients were older (69 ± 13 vs 60 ± 13 years, P < 0.001), had significantly higher rate of baseline risk factors, and had longer symptoms duration prior to hospital admission (mean 460 ± 815 minutes vs 367 ± 596 minutes, P = 0.04). There was no significant difference in door‐to‐balloon time (mean 45 ± 18 minutes vs 44 ± 41 minutes, P = 0.647).

Table 1.

Baseline Patients' Characteristics

| Variable | Males, n = 1075 | Females, n = 271 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 60 ± 13 | 69 ± 13 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 415 (39%) | 171 (63%) | < 0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 490 (46%) | 151 (56%) | 0.003 |

| History of smoking, n (%) | 580 (54%) | 92 (34%) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 215 (20%) | 73 (27%) | 0.016 |

| Prior MI, n (%) | 109 (10%) | 26 (10%) | 0.910 |

| Family history of CAD, n (%) | 190 (18%) | 28 (10%) | 0.003 |

| Symptom duration, mean ± SD | 367 ± 596 | 460 ± 815 | 0.03 |

| Door to balloon time, mean ± SD | 44 ± 40 | 45 ± 17 | 0.439 |

| Multivessel CAD | 614 (57%) | 132 (49%) | 0.014 |

| Peak CPK, mean ± SD | 1274 ± 1406 | 1066 ± 1304 | 0.117 |

| LV ejection fraction, mean ± SD | 48 ± 8 | 46 ± 8 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; LV, left ventricular; MI, myocardial infarction; SD, standard deviation.

In‐Hospital Complications and Short‐Term Mortality

Overall, females suffered from more in‐hospital complications, including renal failure (16% vs 9%, P < 0.001), mechanical ventilation (7% vs 3%, P = 0.004), heart failure (13% vs 7%, P = 0.007), atrial fibrillation (7% vs 4%, P = 0.010), and bleeding episodes (6% vs 1%, P < 0.001) (Table 2). Of a total of 28 bleeding events, 10 (36%) were related to entry site, 6 of which (60%) occurred in females. Thirty‐day mortality was also significantly higher among females (5% vs 2%, P = 0.008).

Table 2.

In‐Hospital Complications and Mortality

| Variable | Males, n = 1075 | Females, n = 271 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiogenic shock/need for IABC, n (%) | 37 (3%) | 15 (5%) | 0.110 |

| In hospital CABG, n (%) | 24 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 0.110 |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 37 (3%) | 20 (7%) | 0.004 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 80 (7%) | 34 (13%) | 0.007 |

| Acute renal failure, n (%) | 92 (9%) | 44 (16%) | < 0.001 |

| Severe bradycardia/cardiac pacemaker, n (%) | 44 (4%) | 18 (5%) | 0.113 |

| Ventricular fibrillation/tachycardia, n(%) | 60 (6%) | 13 (5%) | 0.610 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 42 (4%) | 18 (7%) | 0.010 |

| Major bleeding/blood transfusion, n (%) | 13 (1%) | 15 (6%) | < 0.001 |

| 30‐day mortality, n (%) | 21 (2%) | 13 (5%) | 0.008 |

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; IABC, intra‐aortic balloon counterpulsation.

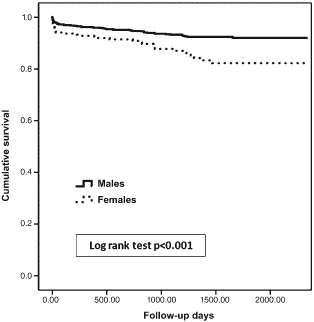

Effect of Gender on Mortality

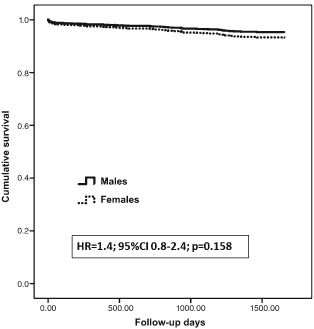

Over a mean period of 2.7 ± 1.6 years, 100 (7.4%) patients from the entire cohort died, of whom 34 (12.5%) were females and 66 (6%) were males (P < 0.001). In multivariate logistic regression, female gender was not found to be associated with 30‐day mortality. The only predictors found to increase the risk for 30‐day mortality were acute renal failure (odds ratio [OR]: 4.5, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.5‐12, P = 0.005) and mechanical ventilation (OR: 13, 95% CI: 4–39, P < 0.001), with only marginally significant associations with heart failure, age, and time to emergency room (ER). When analyzing the Kaplan‐Meier survival curves with the unadjusted log‐rank test model (Figure 1), females had a significant increase in mortality during the follow‐up period. However, in the multivariate adjusted Cox regression model following adjustment for baseline comorbidities as well as complications that were found significant in the univariate models, female gender was not found to be an independent predictor of long‐term mortality following STEMI (Table 3, Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Kaplan‐Meier survival curves.

Table 3.

Regression Models

| 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | Lower | Upper | P Value |

| Gender | 1.443 | 0.867 | 2.401 | 0.158 |

| Age | 1.050 | 1.027 | 1.072 | < 0.001 |

| Symptom duration | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.322 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.296 | 0.804 | 2.090 | 0.287 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.863 | 0.555 | 1.343 | 0.515 |

| Family history | 0.373 | 0.113 | 1.235 | 0.106 |

| Smoking history | 1.225 | 0.760 | 1.974 | 0.404 |

| Hypertension | 1.057 | 0.640 | 1.747 | 0.829 |

| Admission creatinine | 1.429 | 0.726 | 2.812 | 0.302 |

| CAD extent | 1.221 | 0.780 | 1.911 | 0.383 |

| LV ejection fraction | 0.979 | 0.955 | 1.004 | 0.095 |

| Acute renal failure | 1.977 | 1.147 | 3.407 | 0.014 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 3.484 | 1.944 | 6.244 | < 0.001 |

| Heart failure | 2.528 | 1.500 | 4.260 | < 0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.067 | 0.470 | 2.425 | 0.877 |

| Major bleeding | 0.379 | 0.114 | 1.259 | 0.113 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; LV, left ventricular.

Figure 2.

Cox proportional hazards survival plot. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Discussion

In the present work, performed in a large cohort of consecutive STEMI patients treated with PPCI, female gender was associated with higher rates of short‐term death as well as in hospital complications. In spite of the increased risk of death noted in the unadjusted models, long‐term mortality did not differ between genders when multivariate adjusted models were used.

Previous reports performed in the thrombolysis era have shown that female gender is an independent risk factor for mortality among STEMI patients.1, 13 Those reports had evaluated broader subsets of acute coronary syndromes patients combined,9 as well as a variety of treatment options, which included thrombolysis, conservative treatments,11 and different types of coronary interventions.5 Recent reports evaluating the use of PPCI among STEMI patients have shown controversial results,3, 4, 14, 15, 16 the majority of which have shown higher mortality rates among females, but in most of them this significant difference diminished following multivariate analysis.14, 17, 18 Few studies have shown that female gender is an independent predictor for in‐hospital mortality.4, 19 In only 1 report3 on a cohort of 1937 patients with acute myocardial infarction, female gender was an independent predictor of lower mortality rates at 1‐year follow‐up. The reason for these different results can be explained by the different study inclusion criteria,20, 21 different size of study populations,11 and different treatment options.5

Consistent with previous reports,1, 4, 13 we also found that female gender was associated with advanced age and a higher prevalence of baseline risk factors that include diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and longer time from onset of symptoms to the ER. Female patients also had higher short‐term and long term‐mortality. However, for long‐term mortality tested in multivariate adjusted models, we did not find any statistical difference between genders.

Most of the previous reports have evaluated a small number of complications following STEMI. In our cohort, females had an increased risk of in‐hospital complications that included renal failure, mechanical ventilation, heart failure, low ejection fraction, atrial fibrillation, and bleeding. These data are supported by previous reports. Both Gevaert et al22 and Sederholm Lawesson et al23 showed that female gender was independently associated with renal dysfunction at admission in PCI‐treated patients. Furthermore, Sciagra et al24 showed that among 460 patients with acute myocardial infarction, there was a significant gender‐related difference with left ventricular ejection fraction decreasing more sharply in females than in males. The higher rate of complications can also be explained by the higher baseline risk factors. Furthermore, our data showed that females had a longer time from the onset of symptoms to arrival to the ER (mean, 460 minutes vs 367 minutes). The reason for this difference is unknown, and may be explained by the more atypical symptoms experienced by females or by underdiagnoses by the medical staff due to reduced awareness of STEMI presentations among females.25 However, it is important to mention that the median time from symptoms onset to ER is only 120 minutes, which is in the recommended range mentioned in recent practice guidelines12 based on the results of previous reports26, 27 that showed that the greatest benefit gained from reperfusion therapy occurs within the first 2 to 3 hours of symptom onset.

Importantly, our study showed no significant difference in door‐to‐balloon time, suggesting that the treatment was identical in both genders, which is in contrast to previous reports.25, 28

Our findings may be limited to broader populations both by the specific patient subset analyzed as well as by its design. This was a single‐center, retrospective, observational study, and as such may have been subject to bias, even though we included consecutive patients and attempted to adjust for multiple confounding factors using multivariate models. We acknowledge that the relatively small number of females reported here reduces the statistical power of our results. Despite this, our report is unique by its focused population subset, including only consecutive STEMI patients, which were all treated by PPCI and were evaluated for both mortality and a wide range of complications. Another limitation is the inclusion criteria of typical history of acute MI chest pain, because females are known to present with atypical symptoms of acute MI.4 This can explain the longer time from the onset of symptoms to arrival at the ER and for that reason the difference in mortality. In view of that, time from symptom onset to the ER has been incorporated in our multivariate analysis.

Conclusion

We have found that among patients with STEMI treated by PPCI, female gender was associated with higher short‐term mortality and complications rates in comparison to males. Long‐term mortality, however, did not differ between genders when multivariate adjusted models were used. Our findings might help serve the efforts performed to raise the awareness of coronary artery disease as well as STEMI among females, which may still be perceived as a disease of males, and by doing so may increase the use of preventative measures among females.29

Drs Laufer‐Perl and Shacham contributed equally to this article.

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Vaccarino V, Parsons L, Every NR, et al. Sex‐based differences in early mortality after myocardial infarction. National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Participants. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gan SC, Beaver SK, Houck PM, et al. Treatment of acute myocardial infarction and 30‐day mortality among women and men. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mehilli J, Kastrati A, Dirschinger J, et al. Sex‐based analysis of outcome in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated predominantly with percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2002;287:210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vakili BA, Kaplan RC, Brown DL. Sex‐based differences in early mortality of patients undergoing primary angioplasty for first acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;104:3034–3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. D'Ascenzo F, Gonella A, Quadri G, et al. Comparison of mortality rates in women versus men presenting with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:651–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jneid H, Fonarow GC, Cannon CP, et al. Sex differences in medical care and early death after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;118:2803–2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Milcent C, Dormont B, Durand‐Zaleski I, et al. Gender differences in hospital mortality and use of percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction: microsimulation analysis of the 1999 nationwide French hospitals database. Circulation. 2007;115:833–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berger JS, Elliott L, Gallup D, et al. Sex differences in mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2009;302:874–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Duvernoy CS, Smith DE, Manohar P, et al. Gender differences in adverse outcomes after contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention: an analysis from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium (BMC2) percutaneous coronary intervention registry. Am Heart J. 2010;159:677–683.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Woo JS, Kim W, Ha SJ, et al. Impact of gender differences on long‐term outcomes after successful percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2010;145:516–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Radovanovic D, Nallamothu BK, Seifert B, et al. Temporal trends in treatment of ST‐elevation myocardial infarction among men and women in Switzerland between 1997 and 2011. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2012;1:183–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:e78–e140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Malacrida R, Genoni M, Maggioni AP, et al. A comparison of the early outcome of acute myocardial infarction in women and men. The Third International Study of Infarct Survival Collaborative Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Antoniucci D, Valenti R, Moschi G, et al. Sex‐based differences in clinical and angiographic outcomes after primary angioplasty or stenting for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brodie BR. Why is mortality rate after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty higher in women? Am Heart J. 1999;137:582–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vacek JL, Rosamond TL, Kramer PH, et al. Sex‐related differences in patients undergoing direct angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1993;126:521–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eitel I, Desch S, de Waha S, et al. Sex differences in myocardial salvage and clinical outcome in patients with acute reperfused ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: advances in cardiovascular imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ferrante G, Corrada E, Belli G, et al. Impact of female sex on long‐term outcomes in patients with ST‐elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:749–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Benamer H, Tafflet M, Bataille S, et al. Female gender is an independent predictor of in‐hospital mortality after STEMI in the era of primary PCI: insights from the greater Paris area PCI Registry. EuroIntervention. 2011;6:1073–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roffi M, Radovanovic D, Erne P, et al. Gender‐related mortality trends among diabetic patients with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction: insights from a nationwide registry 1997–2010. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2013;2:342–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krishnaswami A, Chang TI, Jang JJ, et al. The association of gender to cardiovascular outcomes after coronary artery revascularization in patients with end‐stage renal disease. Clin Cardiol. 2014;37:546–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gevaert SA, De Bacquer D, Evrard P, et al. Renal dysfunction in STEMI‐patients undergoing primary angioplasty: higher prevalence but equal prognostic impact in female patients; an observational cohort study from the Belgian STEMI registry. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sederholm Lawesson S, Todt T, Alfredsson J, et al. Gender difference in prevalence and prognostic impact of renal insufficiency in patients with ST‐elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart. 2011;97:308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sciagra R, Parodi G, Migliorini A, et al. Evaluation of the influence of age and gender on the relationships between infarct size, infarct severity, and left ventricular ejection fraction in patients successfully treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. J Nucl Cardiol. 2010;17:444–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rezaee ME, Brown JR, Conley SM, et al. Sex disparities in pre‐hospital and hospital treatment of ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. Hosp Pract. 1995;41:25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2569–2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gershlick AH, Banning AP, Myat A, et al. Reperfusion therapy for STEMI: is there still a role for thrombolysis in the era of primary percutaneous coronary intervention? Lancet. 2013;382:624–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Valente S, Lazzeri C, Chiostri M, et al. Gender‐related difference in ST‐elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty: a single‐centre 6‐year registry. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19:233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ayanian JZ, Epstein AM. Differences in the use of procedures between women and men hospitalized for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]