Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to examine job lock in relation to well-being among workers in the U.S. Job lock refers to a circumstance in which a worker would like to retire or stop working altogether, but perceives that they cannot due to needing the income, and/or health insurance. Prior to examining job lock as a potential predictor of life satisfaction we first investigated the construct validity of job lock. Results from a sample of N=308 workers obtained via MTurk indicated that job lock due to financial need was more strongly associated with continuance and affective organizational commitment and job satisfaction compared to health insurance job lock. Job lock due to health insurance needs was related to a dimension of career entrenchment. We then tested hypotheses regarding the relation between job lock at T1 and life satisfaction at T2, two years later. Specifically, we hypothesized that perceptions of job lock would be negatively related to life satisfaction. Using two independent samples from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), we found that both types of job lock were highly prevalent among workers age 62–65. Job lock due to money was significantly associated with lower life satisfaction 2 years later. The findings for job lock due to health insurance were mixed across the two samples. This study was an important first step toward examining the relation between job lock, an economic concept, in relation to workers’ job attitudes and well-being.

There are a number of important demographic, economic, and psychological reasons why many individuals are working longer or planning to work longer – that is, working later than traditional retirement ages observed in prior years (Burtless & Quinn, 2002; Banerjee & Blau, 2013; Fisher, Chaffee, & Sonnega, 2016; Shultz & Wang, 2011). For example, people are living longer, healthier lives than in decades past. Increased longevity means that individuals maintain health long enough to remain in the workforce until later ages. Furthermore, changes have been made to the age of eligibility for government pensions. Although the earliest age of eligibility for government retirement pension (Social Security) in the U.S. is age 62, individuals who wait to claim their Social Security until the age of eligibility for full retirement benefits will receive higher monthly payments compared to those who opt for benefits earlier. The age of eligibility for full benefits has begun to increase from 65 to 67 years of age, and additional financial incentives are in place to encourage workers to delay Social Security claiming until age 70. Other institutional changes have also encouraged working longer, such as the abolition of the Social Security earnings test, anti-age discrimination laws, and elimination of mandatory retirement.

Outside the U.S., almost all of the 34 countries comprising the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have enacted policies to increase retirement ages due to macroeconomic concerns (OECD, 2013). During the last decade, many of the OECD countries have increased the age of eligibility for government retirement pensions, and by 2050, most will have increased the retirement age to 67. In addition, financial incentives for early retirement have been removed and replaced by incentives to delay retirement. As a result, a trend toward later retirement age is likely to be evident outside the U.S. as well. Altogether these changing patterns of labor force participation raise important questions regarding workers’ decisions to remain in the workforce and the consequences of working longer (Fisher, Ryan, & Sonnega, 2015; Furunes et al., 2015).

The purpose of the present study is to examine the relation between working past age 61 (as 62 is the earliest age of eligibility for Social Security retirement benefits in the U.S.), job lock, and psychological well-being. Job lock refers to a circumstance in which a worker would like to retire or stop working altogether but perceives that they cannot due to needing the income and/or employer-provided health insurance. This study will fill a gap in the literature, as little is currently known about psychological well-being associated with working until later ages and particularly beyond the early age of eligibility for Social Security retirement benefits. The focus of this research is on older workers who continue to work, the extent to which continued work is due to job lock, and the consequences of doing so in terms of life satisfaction. Next we define job lock and then present the theoretical background that guides our study and describe how this work fits into the broader literature of work, aging, and retirement.

Defining Job Lock

As commonly defined, job lock refers to the notion that workers do not perceive that they have a choice – they must continue to work despite their desire to retire. Note that being in a state of job lock has an implied time course: individuals are likely to update this perception as their economic, health, or job experiences or circumstances change. Prior job lock research has primarily been published in economics (e.g., Cutler, 2014; Gruber & Madrian, 2002; Madrian, 1993) and work disability (Wilkie, Cifuentes, & Pransky, 2011) literatures. Most of the economic papers about job lock conceptualized the construct as a macroeconomic labor supply issue as well as an individual retirement decision that can limit job mobility (Cutler, 2014; Gruber & Madrian, 2002). Economic research has pointed to two potential sources of job lock: financial need and health insurance.

Financial need

The retirement decision is affected by financial resources potentially available for retirement (Beehr, Glazer, Nielson, & Farmer, 2000; Kim & Feldman, 1998; Mein et al., 2000; Pienta & Hayward, 2002).The major sources of retirement income are government-provided retirement benefits (Old Age, Survivor and Disability Insurance (OASDI) through the Social Security Administration in the U.S.), public and private defined benefit (DB) and defined contribution (DC) pensions, and private savings.

Income and Wealth

Prior research has found that most individuals retire and leave the workforce altogether when they can afford to do so (Beehr et al., 2000) and that wealth and labor income are tied to retirement timing (Bütler, Huguenin, & Teppa, 2004; Dorn & Sousa-Poza, 2005; Fisher et al., 2016) such that higher income and assets are associated with expectations of earlier retirement (Mermin, Johnson, & Murphy, 2007) and generally greater wealth is linked to earlier retirement (Bloemen, 2011; Honig, 1998; Szinovacz & Deviney, 2000). Yet some individuals may reach retirement without sufficient savings to maintain their standard of living in retirement (Munnell & Sass, 2008). For example, Hurd and Rohwedder (2012) showed that as many as 29% of new retirees (age 66 to 69) may not be adequately prepared for retirement in the sense that they do not have enough money to live on until death. They found that certain sub-groups, such as single women and especially those with less than a high school education, are at risk of inadequate financial preparation for retirement. Health permitting, such individuals may continue working simply to sustain themselves. Other workers with greater financial resources may still perceive themselves as “locked” in that they perceive that they need the income earned from work to help pay for children’s higher education expenses, to afford travel or maintain a certain lifestyle in retirement, or due to market volatility associated with various types of retirement savings accounts, including DC pension plan accounts and individual retirement accounts (IRAs). These potential sources of perceived job lock are a fertile area for future research.

Employer-provided pensions

In addition to government pensions (e.g., Social Security in the U.S.), employer-provided pensions are typically an important source of retirement income for American workers. Employer pensions have undergone a significant shift during the past two decades, from DB to DC plans. In brief, DB plans provide an annuity payment, usually until death, which depends largely on job type and employee years of service with a particular firm. In contrast, DC pension plans allow workers to save a certain amount in a retirement account that can be drawn down at retirement. Typical incentives built into DB plans (i.e., the value of DB pensions increasing slowly at first then more rapidly at 10–20 years and a required period of vesting for eligibility) encouraged younger workers to remain with the same employer (Gustman, Mitchell, & Steinmeier, 1994). Because DB plans are tied to a particular employer (i.e., typically they are not portable), DB pension plans can create a pension-related job lock (Ulrich, 2001). At around 20–30 years of service the value tends to drop, which encourages retirement (Friedberg, 2007). Thus, presence of a DB pension is typically associated with earlier age of retirement. On the other hand, DC pension plans are generally portable and do not incentivize retirement at specific ages. However, employer matching contributions to DC plans may also be an attractive benefit that may encourage employees to remain with their employer, potentially creating an alternative, albeit less binding, form of job lock.

Health insurance

Job lock may result from circumstances in which an individual would prefer to retire but continues working in order to obtain employer-provided health insurance coverage. In their review of the health insurance and retirement literature, Gruber and Madrian (2004) found solid empirical support across multiple studies that health insurance affects retirement decisions. Specifically, they reported that the availability of health insurance after one has retired (i.e., retiree health insurance) increases the odds of retirement by 30–80%. These findings were consistent across various empirical methods, models, and datasets. Older workers, and particularly those who are less healthy or more in need of healthcare, may be less willing to retire from a job that offers health insurance if insurance would otherwise not be available, be very expensive, or offer less coverage. Prior to the U.S. Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) and recent changes to U.S. health insurance policy, 90% of individuals with private health insurance obtained coverage through their employment or employment of a family member (Gruber & Madrian, 2004). One of the provisions of the ACA was to require that employers make policies available to their workers.

In the U.S., age 65 is significant because it is the age when all Americans become eligible for health insurance through Medicare. This has implications for health insurance-related job lock. For example, Cutler (2002) studied older workers in the U.S. who were financially and psychologically ready to retire but remained employed in order to retain employer-provided health insurance until reaching the age of eligibility for Medicare. A review of this literature concluded that health insurance is indeed an important factor related to whether and when individuals retire, especially for secondary earners (who are predominantly married women; Fisher et al., 2016; Gruber & Madrian, 2004; Murasko, 2008). Specifically, this research has found that among households with dual earners, one spouse may work primarily to obtain employer-provided health insurance or supplementary insurance for the household. Relevant to the aims of the present study, they also found that there was very little research on the welfare effects of this outcome (Gruber & Madrian, 2002). Rashad and Sarpon (2008) conducted a literature review and concluded that there is evidence of health-insurance related job lock in the U.S. They presented empirical results using data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) to study individuals with health insurance in which they compared those with and without employer-provided health insurance. Individuals with employer-provided health insurance were less likely to leave a job and more likely to stay on the job longer than those with other sources of health insurance. Boyle and Lahey (2010) found that new access to non-employer provided health insurance decreases full-time work and increases part-time employment among older workers. More research is needed to build our understanding of employer-provided health insurance and labor mobility, particularly given the passage of the ACA.

Work disability researchers are also concerned about job lock because individuals may continue to work in spite of injuries and poor working conditions in order to obtain employee benefits when they would otherwise leave that job or retire altogether. Job lock has been conceptualized in multiple ways in the work disability literature. For example, Pransky and colleagues conceptualized job lock as existing when a worker remains on the job to obtain employee benefits, including wages, health insurance, or perhaps other employee benefits but would otherwise prefer to leave (e.g., Benjamin, Pransky, & Savageau, 2008; Wilkie et al., 2011). Huysse-Gaytandjieva, Groot, and Pavlova (2013) took a broader approach by defining job lock as generally feeling “stuck” at work. Specifically, Huysse-Gaytandjieva et al. (2013) used data from the British household panel survey and operationalized job lock as reporting job dissatisfaction and remaining in the same job for at least two years. Both of these studies incorporated psychological aspects of work – namely job dissatisfaction – in the definition, which extends the conceptualization of job lock beyond simply a perception of economic status on its own. Although this was the first study to integrate economic and psychological factors to study job lock, it did not account for the key economic factors (e.g., employer-provided health insurance and pension plans) that create job lock in the U.S.

We define job lock as a circumstance in which a worker would like to retire but perceives that he or she cannot due to needing the income and/or employer-provided health insurance. Our definition is consistent with prior research (e.g., Benjamin et al., 2008; Wilkie et al., 2011) and takes both economic and psychological factors into account – based on considering income and health insurance as economic factors as well as the individual’s perceptions regarding the desire to leave his or her employment situation. Next we summarize relevant theories in the work, aging, and retirement literature that guide our investigation of job lock and well-being.

Theoretical Background

The work and retirement literature has demonstrated many possible reasons why workers at older ages (e.g., older than 62 years of age) may continue to work vs. choose to retire (Barnes-Farrell, 2003; Fisher et al., 2015; Kanfer, Beier, & Ackerman, 2013). For example, the push/pull model of retirement (Barnes-Farrell, 2003; Shultz, Morton, & Weckerle, 1998) suggests that some workers will retire because they are pushed out of the work role (e.g., employer incentives to retire, declines in health status or job-related functional capacity, i.e., decreased work ability, negative job conditions), whereas other individuals will be pulled toward retirement for desirable aspects of retirement, including non-work reasons (e.g., to travel or spend time with family; caregiving responsibilities). In this article we focus on working until later ages and consequences of continued work. Fisher et al. (2015) suggested that the push/pull model could be applied not only in terms of being “pushed” out of work or “pulled” toward retirement, but that some workers may be “pushed” to continue working primarily due to economic factors, such as to earn wages and/or employer-provided benefits (i.e., retirement, health insurance). This is particularly the case when an individual does not have control over his or her work situation and experiences job lock – a preference to retire, but a need to continue working due to economic necessity: either for pay, health insurance benefits, or both. Fisher and colleagues (2015) also indicated that older workers could be “pulled” toward work because they derive satisfaction or meaningfulness from their work, work in jobs with desirable characteristics (e.g., lower job demands, higher levels of autonomy), and other resources (e.g., social support). In other words, workers are pulled to continue working if they are not aiming to leave undesirable work situations and/or they are not enticed by non-work activities or roles.

Two additional theories guide our investigation regarding perceptions of job lock and psychological well-being: 1) rational choice theory and 2) a resource-based perspective. Rational choice theory, grounded primarily in economics, posits that individuals make decisions based on their preferences and the constraints or choices they face (Becker, 1976; Hatcher, 2003). According to rational choice theory, individuals make work and retirement decisions based on their assessment of necessary economic resources. This assessment is a function of the external economic context as well as workers’ financial status. Based on rational choice theory, individuals’ perceptions of job lock are the result of rational economic decisions about their need for income and/or employer-provided health insurance.

Similarly, Wang, Henkens, and van Solinge (2011) proposed a resource-based theory which suggests that individuals’ adjustment to retirement is related to the resources that they have before and after retirement. Specifically this theory identified multiple types of resources (e.g., physical, cognitive, motivational, financial, social, and emotional) that facilitate the retirement adjustment process. Resources most relevant to perceptions of job lock include financial and emotional (affective) resources. For example, greater financial resources would be associated with being less likely to experience job lock. Greater affective resources in the form of positive attitudes about one’s job and work organization would also be associated with being less likely to experience job lock.

Altogether, understanding the motivation and decision to work or retire is complex (Kanfer et al., 2013). There are multiple reasons that can factor into this process, but generally there may be two categories of people who make the decision to continue working: those who want to continue working, and those who feel that they have to for financial or other economic (e.g., health insurance) reasons. In our examination of job lock, we focus on individuals in the latter of these two categories. We apply the aforementioned theories in the retirement literature to consider both economic and psychological factors involved in the work motivation and retirement process to improve our understanding of perceived job lock and life satisfaction.

Study 1 – Job Lock, Continuance Organizational Commitment, Career Entrenchment and Job Satisfaction

Although the ultimate objective of our study was to examine the relation between job lock and well-being, we began by undertaking a preliminary investigation to examine the construct validity of job lock. We sought empirical evidence to clarify the relations among similar constructs by correlating job lock with other constructs that have been investigated in relation to work and satisfaction in retirement, including continuance organizational commitment, affective organizational commitment, career entrenchment, and job satisfaction. We chose these concepts in order to better understand how job lock is related to other job attitudes known to be correlated with turnover intentions and retirement behavior (Barnes-Farrell, 2003; Carson & Carson, 1997; Herrbach, Mignonac, Vandenberghe, & Negrini, 2009).

Continuance Organizational Commitment

Job lock is conceptually very similar to a concept in the organizational psychology and management literatures known as continuance organizational commitment (e.g., Mathieu & Zajac, 1990; Meyer & Allen, 1991). Continuance commitment refers to the perceived costs of leaving an organization, which may potentially include the financial and insurance costs discussed above. Aside from continuance organizational commitment, two other organizational commitment constructs in Meyer and Allen’s (1991) seminal paper are affective commitment, representing an employee’s feelings toward the organization, and normative commitment, which refers to a worker’s sense of obligation to remain with his/her employer. Meta-analytic results have demonstrated that all three types of organizational commitment are related to many important outcomes including job satisfaction, withdrawal cognition, and turnover (Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, 2002).

Prior research has found a small negative linear relation between continuance organizational commitment and retirement (e.g., r = −.07, p < .05; Smith, Holtom, & Mitchell, 2011). Relations between other dimensions of organizational commitment and retirement were stronger (e.g., r = −.20, p < .05 for both affective and normative commitment, respectively) such that individuals with higher levels of affective or normative organizational commitment are less likely to retire. Zhan, Wang, and Yao (2013) found that career commitment and organizational commitment predicted bridge employment decisions and that economic stress moderated the relation between the commitment variables and bridge employment decisions. However, no research to date has compared measures of job lock to organizational commitment.

Likewise, career entrenchment is a construct similar to job lock but has received little empirical attention in this context. Career entrenchment refers to employees’ perceptions of “immobility resulting from substantial economic and psychological investments in a career that make change difficult” (Carson, Carson, Phillips, & Roe, 1996, p. 274). Although it was originally conceptualized as a three-dimensional construct, Blau (2001) provided evidence to support a two-dimensional structure. The accumulated costs dimension represents the time, money, and emotional investment that would be lost if one pursued a new occupation, and the limited alternatives dimension represents a perceived lack of available options for pursuing a new occupation.

The relation between job lock and continuance organizational commitment can be explained by rational choice theory. Rational choice theory indicates that individuals will make rational economic decisions about their need for income and/or employer-provided health insurance. Because job lock occurs when an individual would prefer to leave his/her current job but perceives a need to remain on the job for income or health insurance, and continuance organizational commitment is defined as the perceived costs of leaving one’s organization, we hypothesized that job lock would be moderately positively correlated with continuance organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 1: Job lock and continuance organizational commitment are positively related. That is, individuals who report experiencing job lock will have higher levels of continuance organizational commitment than those who do not report job lock.

Similarly, because job lock occurs when a worker would like to leave their work organization, we expect that experiencing job lock is associated with less positive feelings toward the organization. By definition, affective commitment refers to identifying with the goals of the organization and wants to remain a part of the organization. According to the push/pull model of retirement, more positive job attitudes will lead to intentions to remain with an organization, and in turn will result in continued work. On the other hand, negative job attitudes will be related to greater intentions to leave work altogether. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 states that:

Hypothesis 2: Job lock and affective organizational commitment are negatively related. In other words, reports of job lock will be related to lower levels of affective organizational commitment.

Next we examined the relation between job lock and career entrenchment. Given that the definition of career entrenchment indicates an investment of psychological and economic resources, it should follow that leaving one’s job would involve losing resources so people would stay at work to avoid this loss. Therefore based on rational choice theory, which suggests that individuals make decisions based on rational choices based on preferences and constraints, we hypothesized that job lock would be positively related to both dimensions of career entrenchment because employees who are more invested in their career and perceive a lack of alternatives are more likely to feel that they are “locked in.” However, we did not expect a strong correlation between job lock and career entrenchment because our definition of job lock focuses on economic reasons for working (e.g., money, health insurance) rather than alternative reasons (e.g., having invested time and money in one’s education to obtain their current job).

Hypothesis 3: Job lock and career entrenchment are positively related (i.e., individuals who experience job lock will report higher levels of career entrenchment).

Based on the push/pull model, we also inspected the relation between job lock and job satisfaction. Given the aspect of our definition of job lock that indicates workers’ preferences to leave work if they were financially able, it is likely that workers who report job lock are less satisfied with their jobs. Furthermore, Huysse-Gaytandjieva et al. (2013) conceptualized job lock as the situation that results from dissatisfied workers not adapting to their work environment.

Hypothesis 4: Job lock and job satisfaction are negatively related. In other words, reports of job lock will be associated with lower levels of job satisfaction.

Study 1 - Method

Participants

Participants in this study included a heterogeneous sample of working adults (employed at least 20 hours per week) in the U.S. recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) site to complete two surveys (a screening survey followed by the main survey). First we deployed a screening survey to 1,045 individuals in order to 1) recruit only participants from the U.S. who were working 20+ hours per week for an organization for pay (i.e., in addition to MTurk), and 2) achieve an age-diverse sample because MTurk workers tend to be younger than the general U.S. population (Goodman, Cryder, & Cheema, 2013). The screening study could be viewed only by participants in the U.S., and geographical tracking was used (the region from which the IP address came from was recorded) to verify that all survey responses came from U.S. workers. Individuals were “qualified” (invited) to take the main survey based on their responses to the screening survey. We specifically targeted those who were age 40+ prior to extending the survey invitation to all those who qualified based on hours worked. Among the 1,045 individuals who completed the screening survey, 341 (33%) completed the main survey. In the main survey we included two items to detect insufficient effort responding (IER; e.g., “Please select “strongly agree” for your response to this question”). Individuals who incorrectly responded to both of these items were removed from the dataset (n = 21). Additionally, individuals who indicated that they worked fewer than 20 hours per week were removed from the dataset (n = 12). The final sample size for analysis was N= 308. The sample was 53% male (n = 162). Number of hours worked per week ranged from 20 to 84; the average was M = 39 hours (SD = 7.11). Participants’ ages ranged from 18 – 69; the average age was M = 35.4 years (SD = 11.25). Participants’ jobs varied and included, for example, teacher, cashier, law enforcement officer, and nurse.

Measures

Job lock

We assessed job lock using two items identical to what has been used by Wilkie et al. (2011) as well as in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a large nationally representative panel study sponsored by the National Institute on Aging and the Social Security Administration and conducted by the University of Michigan (U01AG009740). These items were “Right now, would you like to leave work altogether, but plan to keep working because you need the money? (Yes/No) and “Right now, would you like to leave work altogether, but plan to keep working because you need health insurance?” (Yes/No). We also asked participants “Do you have access to health insurance provided by your employer?” (Yes/No) and only examined job lock among those who reported having access to health insurance by their employer. Job lock was coded individually for money and insurance job lock. Job lock due to money was coded as 0 = no lock and 1 = locked due to money; job lock due to health insurance was coded as 0 = no lock and 1 = locked due to insurance.

Organizational commitment

We used the organizational commitment scales by Allen and Meyer (1990) to assess three dimensions of organizational commitment. Each dimension was assessed using 8 items on a 5-point Likert-type response scale ranging from 1=Strongly Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree. Negatively-worded items were reverse-coded and scale scores were constructed by calculating the mean across the eight items within each dimension (α = .79 for continuance commitment; α = .91 for affective commitment; α = .86 for normative commitment).

Career entrenchment

We measured career entrenchment using Carson, Carson, and Bedeian’s (1995) two-dimensional scale. The accumulated costs dimension (α = .89) contained 8 items, and the limited alternatives dimension (α = .90) contained 4 items. All items were assessed on a 5-point Likert-type response scale ranging from 1=Strongly Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree.

Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction was assessed with three items from the Michigan Organizational Effectiveness Questionnaire (Cammann, Fichman, Jenkins, & Klesh, 1979). An example item is “All in all, I am satisfied with my job.” One of the items, “In general, I don’t like my job,” was negatively-worded. The three items demonstrated a high level of internal consistency reliability (α = .94).

Study 1- Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations for all study variables are shown in Table 1. Among the participants in this study, most reported experiencing job lock: 91% reported job lock due to money and 78% reported job lock due to needing health insurance. We computed point-biserial correlations to examine the relation between job lock (a dichotomous variable) and other study variables (which were measured using a more continuous measurement scale), and “standard” Pearson correlation coefficients among the other study variables. Results showed that job lock due to money and job lock due to health insurance were positively, moderately related to one another (r = .41, p < .05). We found some support for Hypothesis 1, which stated that individuals who reported job lock would report higher levels of continuance organizational commitment. Job lock due to money had a small positive linear relation with continuance organizational commitment (r = .20, p < .05) whereas the correlation between job lock due to health insurance was also small but not statistically significant given the sample size in this study (r = .13, p > .05). Next we examined the magnitude of the correlations between job lock and affective organizational commitment to test Hypothesis 2. Results provided partial support for Hypothesis 2, as job lock due to money had a small to moderate negative relation with affective commitment (r = −.27, p < .05), although job lock due to health insurance was unrelated to affective commitment (r = −.06, p > .05) given the very small magnitude of the correlation. Hypothesis 3 was partially supported: career entrenchment – specifically accumulated costs had a small positive relation to health insurance job lock (r = .21, p < .05), though it was unrelated to money job lock (r = −.04, p > .05). Lastly, Hypothesis 4 was also partially supported: Job lock due to needing money was negatively related to job satisfaction (r = −.26, p = .05) but job lock due to health insurance was unrelated to job satisfaction (r = −.04, p > .05). Next we present Study 2 and then discuss the results of both studies in the Discussion section.

Table 1.

Study 1 - Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix for All Study Variables

| N | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Job Lock- Money | 308 | 0.91 | 0.29 | ||||||

| 2. Job Lock- Health Insurance | 223 | 0.78 | 0.41 | 0.41** | |||||

| 3. Continuance Commitment | 308 | 3.54 | 0.75 | 0.20** | 0.13 | ||||

| 4. Affective Commitment | 308 | 3.13 | 0.95 | −0.27** | −0.06 | 0.00 | |||

| 5. Job Satisfaction | 308 | 3.61 | 1.04 | −0.26** | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.79** | ||

| 6. Career Entrenchment- Accumulated Costs | 307 | 3.01 | 0.92 | −0.04 | 0.21** | 0.28** | 0.55** | 0.46** | |

| 7. Career Entrenchment- Limited Alternatives | 307 | 3.03 | 0.92 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.49** | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.29** |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Results for job lock – insurance excluded 85 participants who reported not having access to health insurance provided by their employer.

Study 2- Job Lock, Work, and Well-being

Prior research has examined job lock in relation to health and disability outcomes (Wilkie et al., 2011) and job mobility (Rashad & Sarpong, 2008). However, no empirical research to date has related job lock to well-being (e.g., life satisfaction). This issue is of particular importance for understanding work and well-being among older adults. Measures of life satisfaction, an evaluative component of subjective well-being, were initially developed in the 1960s and 1970s, and have been used extensively in social science research since then (Andrews & Withey, 1974; Bradburn, 1969; Campbell, Converse, & Rodgers, 1976; Neugarten, Havighurst, & Tobin, 1961). Life satisfaction is a useful and meaningful index of an individual’s global sense of well-being, which reflects a combination of life circumstances and individual dispositions and has been shown to be sensitive to changing life events such as unemployment or widowhood (Lucas, Clark, Georgellis, & Diener, 2004). In addition, research has demonstrated life satisfaction is important to examine among older adults. For example, well-being is related to health as well as longevity in later life (Diener & Chan, 2011).

The purpose of Study 2 was to examine how job lock is related to work status and subjective well-being two years later among older workers in the U.S. who are approaching the earliest age of eligibility for Social Security retirement benefits. We tested hypotheses based on rational choice theory (Hatcher, 2003; Quinn, Burkhauser, & Myers, 1990) and a resource-based retirement perspective (Wang et al., 2011) regarding the likelihood of continued work and psychological well-being. Based on these theories, we expect that workers will evaluate the resources they have and the resources they need to make rational decisions regarding whether to retire. Psychological, economic, social and other resources they have will affect their perceptions of subjective well-being in older adulthood. As such, individuals who report needing financial resources or health insurance even if they would prefer to retire are more likely to continue working past age 62 compared to those who did not report job lock and will therefore experience lower levels of life satisfaction. Therefore we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 5: Workers’ perceptions of job lock will be negatively related to life satisfaction two years later. That is, workers who report experiencing job lock at Time 1 will report lower levels of life satisfaction at Time 2.

Next we will examine the interaction between job lock and work status two years later in relation to life satisfaction. Taking a resource-based perspective on retirement (Wang & Shultz, 2010), we expect that postretirement life satisfaction will be higher among workers who previously reported experiencing job lock and are no longer working compared to those who did not. In other words, achieving a work status that is consistent with one’s attitudes about work and retirement and presumably perceiving that one has the resources available for retirement will lead to higher levels of life satisfaction post-retirement, particularly among those who previously reported experiencing job lock compared to those who did not. Therefore in Hypothesis 5a we predict that there will be an interaction between job lock, life satisfaction, and work status based on retirement status as follows:

Hypothesis 5a: Individuals who reported being in a job lock situation at Time 1 and who are retired at Time 2 will have higher levels of life satisfaction at Time 2 compared to those who did not previously report job lock and compared to those who are still working at Time 2.

Study 2 - Method

In Study 2 we used two independent samples, both obtained from different waves of the HRS. We describe each of these samples as Sample 1 and Sample 2.

Sample 1

Participants and Procedure

Sample 1 included N=263 participants in the 2008 and 2010 waves of the HRS. The HRS is a U.S. nationally representative panel study that was established as a cooperative agreement between the U.S. National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the University of Michigan (U01 AG009740). HRS data are collected biennially via in-person or telephone “core” interviews and supplemental paper-and pencil questionnaires that assess psychosocial issues. Details about the HRS design are published elsewhere (Sonnega et al., 2014). We limited our analysis sample to those who were in the labor force at the time of their interview in 2008, answered the questions in the psychosocial survey pertaining to job lock in 2008, and individuals aged 62 – 65 in the 2010 wave so that we could obtain information about subsequent work status and well-being. The sample was limited to this age group to consider only those who had newly reached the minimum age of partial or full eligibility for U.S. Social Security retirement benefits at the follow-up assessment. More than half of the sample (61%) were women. The average age of respondents was 63.3 years.

Sample 2

We also sought to replicate our results among workers who met the same criteria but participated in the 2010 and 2012 waves of the HRS. Because the U.S. Affordable Care Act was passed in 2010, this replication allows us to not only cross-validate our results from Sample 1, but also compare results before and after the passage of the Affordable Care Act.

Participants

Participants in Sample 2 were N=348 participants in the 2010 and 2012 waves of the Health and Retirement Study and completely independent from Sample 1. We used the same criteria for selecting the sample for analysis: individuals in the labor force at the time of their interview in 2010, answered the questions in the psychosocial survey pertaining to job lock in 2010, and individuals aged of 62–65 in the 2012 wave so that we could obtain information about subsequent work status and well-being. Sample descriptive statistics were very similar to those in Sample 1: slightly more than half of the sample (54%) was comprised of women. Similar to Sample 1, most (72%) of respondents reported being part of a couple. The average age of respondents was 63.4 years.

Measures

Job lock

Job lock was assessed with two items: “Right now, would you like to leave work altogether, but plan to keep working because you need the money?” and “Right now, would you like to leave work altogether, but plan to keep working because you need health insurance?” Participants answered each item by responding yes or no. These items are the same as those used by Wilkie et al. (2011). For both samples in Study 2, job lock was assessed at baseline (2008 Sample 1; 2010 Sample 2) and was coded individually for money and insurance job lock. Job lock due to money was coded as 0 = no lock and 1 = locked due to money; job lock due to health insurance was coded as 0 = no lock and 1 = locked due to insurance.

Life satisfaction

Life satisfaction was measured with a single overall measure of life satisfaction: “Please think about your life-as-a-whole. How satisfied are you with it?” Participants responded based on the following response scale: 1 = Completely satisfied, 2 = Very satisfied, 3 = Somewhat satisfied, 4 = Not very satisfied, and 5 = Not at all satisfied. This item was reverse coded so that a higher score reflects higher life satisfaction. Although the HRS survey design only included a single item to assess life satisfaction in the core survey, prior research has demonstrated that life satisfaction can be assessed with a reasonable level of reliability and validity (Fisher, Matthews, & Gibbons, 2016).

Work status

To identify those participants at baseline who were in the labor force, our sample selection criteria included all those who were identified as working full-time, working part-time, unemployed, or partly retired. This was used as part of our selection criteria, but was not included in any analyses. Those who were still working at the 2-year follow-up (2010 Sample 1; 2012 Sample 2) were coded as 0 = not working and 1 = working.

Covariates

We also included a large number of covariates measured at baseline that are likely to be related to subsequent work status and life satisfaction. These measures included measures of health status (“Would you say your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?”; values ranging from 1–5) and change in health status (“Compared with your health when we talked to you two years ago, would you say that your health is better now, about the same, or worse?”; values ranging from 0–2). We also included assessments of physical functioning (activities of daily living (ADLs); count of self-reported difficulties with dressing, bathing, eating, getting in and out of bed, using the toilet, and crossing a room; values range from 0–6) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLS; count of self-reported difficulties with preparing meals, buying groceries, using the telephone, taking medications, and managing money; values range from 0–5). To rule out differences in work status and life satisfaction associated with financial status, we included a comprehensive measure of household income (a variable derived from household earnings, capital income, pensions, income from social security, unemployment or workers compensation, income from any other government transfers, and all other household income) from the RAND HRS (Chien et al., 2013). Due to extreme skewness to the household income variable, the analysis used a log-transformed version of this variable. Finally, we controlled for several important demographic variables, including gender (0 = men, 1 = women), coupleness status (0 = not married/partnered, 1 = married/partnered), education (0 = less than high school degree, 1 = high school degree or more), and whether the respondent was covered by a spouse/partner’s health insurance policy (0 = no health insurance from a spouse/partner, 1 = health insurance from a spouse/partner). We also examined pension status, as respondents had the opportunity to report on up to four pensions.

Study 2 - Results

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2 for both Samples 1 and 2. Interestingly, a large proportion of workers reported job lock (73% and 75% due to money and 65% and 62% due to health insurance among workers in Sample 1 and Sample 2 respectively). Pension information was available for approximately 90% of both samples. Among those 90%, 57.9% of participants reported having a pension (60% DC pension, 36% DB pension, and 4% reported having both DC and DB pensions). Pension holdings were similar across both samples.

Table 2.

Study 2 - Descriptive Statistics

| Sample 1 (N = 263) |

Sample 2 (N = 348) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M / % | SD | M / % | SD | |

| Women | 60.8% | 54.3% | ||

| HS Education | 42.6%* | 92.0% | ||

| Married | 69.6% | 71.8 | ||

| Log (Household Income) | 11.2 | 1.05 | 11.2 | 0.87 |

| Insurance from Spouse | 18.6% | 15.5% | ||

| Self-rated Health | 3.52 | 1.01 | 3.58 | 0.92 |

| Change in Self-rated Health | 1.89 | 0.50 | 1.93 | 0.50 |

| ADLs | 0.09 | 0.49 | 0.09 | 0.32 |

| IADLs | 0.16* | 0.45 | 0.04 | 0.28 |

| Work Status | 81.8% | 79.6% | ||

| Job Lock - Money | 73.0% | 75.0% | ||

| Job Lock - Insurance | 64.6% | 62.4% | ||

| Life Satisfaction | 3.85 | 0.86 | 3.88 | 0.75 |

Note:

indicates that Sample 1 is significantly different from Sample 2 (p < .05)

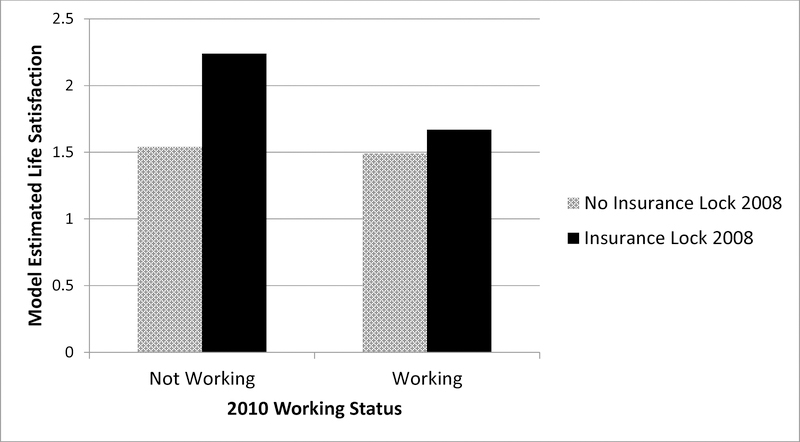

Correlations among study variables for Samples 1 and 2 are presented in Table 3. Results of the hierarchical linear regression predicting life satisfaction in Sample 1 (see Table 4) indicate that job lock due to money (p < .001) and health insurance (p < .05) were significantly associated with life satisfaction, providing support for Hypothesis 5. Surprisingly, although job lock due to money was associated with lower life satisfaction two years later, job lock due to health insurance was associated with higher levels of life satisfaction. However, this finding was qualified by a small but significant interaction between continued work two years later and lock due to insurance (see Table 4). Specifically, continued work versus retirement interacted with health insurance job lock such that life satisfaction was significantly higher for those who previously reported job lock but were no longer working two years later (See Figure 1). This finding provided support for Hypothesis 5a.

Table 3.

Study 2 - Correlation Matrix for Primary Study Variables in Samples 1 and 2

| Sample 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Life Satisfaction | |||||||

| 2. Work Status | −.05 | ||||||

| 3. Money-Lock | −.30*** | 0.23 | |||||

| 4. Insurance-Lock | −.08 | 0.14* | 0.55*** | ||||

| 5. Self-rated Health | 0.26*** | 0.14* | −0.13* | −0.11 | |||

| 6. Change in Self-rated Health | 0.14* | 0.20** | −0.16* | −0.09 | 0.38*** | ||

| 7. ADLs | −0.17** | −.07 | 0.10 | 0.06 | −.24*** | −.21*** | |

| 8. IADLs | −0.15* | −0.16* | 0.09 | 0.04 | −.18** | −0.08 | 0.30*** |

| Sample 2 | |||||||

| 1. Life Satisfaction | |||||||

| 2. Work Status | −0.02 | ||||||

| 3. Money-Lock | −0.17** | 0.00 | |||||

| 4. Insurance-Lock | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.59*** | ||||

| 5. Self-rated Health | 0.31*** | 0.09 | −0.15* | −0.08 | |||

| 6. Change in Self-rated Health | 0.14** | 0.05 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.36*** | ||

| 7. ADLs | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.21*** | −0.06 | |

| 8. IADLs | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.11* | 0.06 | 0.07 |

Table 4.

Study 2 – Sample 1 Hierarchical Regression Results Predicting Life Satisfaction at Time 2

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

β |

SE |

β |

SE |

β |

SE |

|

| Intercept | 3.85*** | 0.05 | 3.85*** | 0.05 | 3.87*** | 0.05 |

| Women | −0.08 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.05 |

| > HS Education | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.06 |

| Married | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Household Income | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Health Insurance from Spouse | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.05 |

| 2008 Self-rated Health | 0.17** | 0.06 | 0.18** | 0.05 | 0.19** | 0.06 |

| 2008 Change in Health | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| 2008 ADLs | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.05 |

| 2008 IADLS | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.05 |

| Working Longer | −0.09 | 0.05 | −0.11 | 0.05 | ||

| 2008 Job Lock- Money | −0.29*** | 0.06 | −0.27*** | 0.06 | ||

| 2008 Job Lock- Insurance | 0.12* | 0.06 | 0.10* | 0.06 | ||

| Job Lock Insurance * Working Longer | −0.10* | 0.05 | ||||

| R2 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.21 | |||

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Figure 1.

Interaction between Working Longer, Health Insurance Job Lock, and Life Satisfaction

The pattern of results in Sample 2 was partially consistent with those from Sample 1 (see Table 5 for results predicting life satisfaction with Sample 2). As in Sample 1, job lock due to money was associated with lower life satisfaction two years later, consistent with Hypothesis 5, although the effect size was smaller in Sample 2. However, the significant main effect of job lock due to health insurance and the interaction of working longer status with lock due to health insurance were not significant in Sample 2, therefore not supporting Hypothesis 5 nor 5a. Upon comparing the results from the two samples, although the health insurance main effect and interaction were not significant in magnitude, the effects were in the same direction as those in Sample 1. When we added type of pension plan(s) as a covariate in the model, the sample size was reduced on account of missing pension data for approximately 10% of each sample. The pattern of results was generally consistent when we added pension variables to the model, but because the sample size was reduced, we chose to report the results without the pension variables included. With regard to education as a covariate, we also conducted an additional analysis with a three-category education variable to differentiate between those with only a high school degree and those with more education (in lieu of the two-category education categorization described previously). The pattern of results with the three-category education variable remained the same.

Table 5.

Study 2 – Sample 2 Hierarchical Regression Results Predicting Life Satisfaction at Time 2

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

β |

SE |

β |

SE |

β |

SE |

|

| Intercept | 3.88*** | 0.04 | 3.88*** | 0.04 | 3.88*** | 0.04 |

| Women | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| > HS Education | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.04 |

| Married | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Household Income | 0.13** | 0.04 | 0.12** | 0.04 | 0.12** | 0.04 |

| Health Insurance from Spouse | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| 2010 Self-rated Health | 0.21*** | 0.04 | 0.20*** | 0.04 | 0.21*** | 0.04 |

| 2010 Change in Health | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| 2010 ADLs | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| 2010 IADLS | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Working Longer | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.04 | ||

| 2010 Job Lock- Money | −.13** | 0.05 | −0.13** | 0.05 | ||

| 2010 Job Lock- Insurance | .08 | 0.05 | .08 | 0.05 | ||

| Job Lock Insurance * Working Longer | −0.01 | 0.04 | ||||

| R2 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.16 | |||

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Discussion

As the trend toward working longer continues, it is important to build our understanding of factors associated with both negative and positive aspects of continued work among older adults. This study was an important first step in investigating psychosocial factors related to continued work and well-being. In particular, we investigated job lock in relation to work attitudes and well-being. Job lock refers to the notion that workers would prefer to leave their jobs altogether but feel they cannot either because they need the money or the health insurance.

First, in Study 1, we conducted an exploratory validation study among a heterogeneous sample of workers across multiple organizations to relate job lock, which has historically been studied in the economic and work disability literature, to psychological variables related to attitudes about continued work, such as continuance and affective organizational commitment and career entrenchment. By relating job lock to organizational commitment, career entrenchment, and job satisfaction, we examined how perceptions of economic resources considered in the context of rational choice theory and a resource-based perspective regarding work and preferences to leave work were related to job attitudes. Overall we found some support for the notion that job lock is related to job attitudes pertaining to continued work. However, results were mixed across the two types of job lock. In particular, job lock due to financial need had a small to moderate relation with continuance and affective organizational commitment and job satisfaction, whereas job lock due to the need for employer-provided health insurance had a small relation to the accumulated cost dimension of career entrenchment.

Although we found relatively little variance in the job lock variable, particularly in Study 1, our results were still quite interesting and provided some useful information regarding the relations among the variables of interest. In general, our findings were consistent with theories about work motivation and job attitudes given similarities in the construct definitions as well as similarities in the way these constructs are measured. Specifically, continuance commitment assesses costs of leaving the organization, and giving up money and/or health insurance certainly relates to costs of leaving one’s employment. The measure of the accumulated costs dimension of career entrenchment is also similar to job lock. In particular, one of the items in the career entrenchment scale addresses the idea of it being costly, income-wise, to switch professions, which is directly related to the concept of job lock due to money. As for the limited alternatives dimension of career entrenchment, someone who perceives that he or she does not have other options or alternatives for work would need to stay at his or her current job for the money. Overall these results suggest that job lock is related to job attitudes that are relevant to and important for understanding retirement decisions. From a human resource management perspective, economic benefits provided to workers (e.g., wages/salary and health insurance) are related to their attitudes about their job and continuing to work for their employer.

Next, in Study 2, we used data from two independent samples in the HRS to investigate the extent to which job lock is related to life satisfaction two years later, taking into account whether individuals were still working or retired at the time that life satisfaction was assessed. Controlling for other factors related to life satisfaction among older adults, results among individuals in the first sample showed that subsequent work status interacted with health insurance job lock such that life satisfaction was significantly higher for those who previously reported job lock but were no longer working two years later. As a follow-up to this finding, we examined whether the proportion of workers who retired two years later differed based on the type of job lock as a possible explanation for differential associations with life satisfaction. Across both samples, 19% of those who were locked due to money were no longer working two years later. Similarly, 18% of those locked due to health insurance were retired at follow-up. The similarity in work status across the two job lock groups suggests that differences in their association with life satisfaction is not necessarily operating through differential work patterns. However, future research should examine this pathway directly.

Results from Study 2 indicated that job lock due to financial reasons is associated with lower life satisfaction; we found evidence to support this hypothesis across two independent samples. Results regarding job lock related to health insurance and life satisfaction were more mixed – the pattern of results was consistent across the two samples, but only reached levels of statistical significance for the first sample, for which data were collected between 2008 and 2010. One explanation for the different results among Sample 2 is that the passage of the Affordable Care Act lessened the strength of the relation between health insurance job lock and life satisfaction. However, further research is warranted to investigate workers’ experiences of job lock in light of the Affordable Care Act. It is also possible that the higher level of education, on average, in Sample 2 may help explain the observed differences in the results between the two samples. Another potential explanation for the differential associations of money versus health insurance job lock with life satisfaction is that there are unique pathways leading to each type of job lock. For example, by definition those that are job locked due to perceived needs for health insurance are in jobs that offer employer-provided health insurance. Those working in jobs that do not offer employer-provided health insurance are likely in lower-paying jobs. As such, it is possible that there are socioeconomic selection factors that differentiate those individuals who feel locked due to health insurance.

We conducted some exploratory analyses to assess whether combining the two types of job lock into a single variable improved the prediction of life satisfaction. When combining the two types of job lock into a single variable, across both samples approximately 21% reported no job lock, 59% reported both types of job lock, and the remainder reported job lock due to money (15%) or health insurance (5.7% in sample 1, and 3% in sample 2). Combining the two types of job lock into a single variable did not improve the predictability of job lock and conceptually reduced our ability to interpret the findings. Specifically, the causes and implications of job lock due to money and job lock due to health insurance are distinct, so combining them into a single variable reduces our ability to identify the source of job lock as well as what could or should be done to reduce perceptions of job lock.

In our current analysis we controlled for several potential SES indicators, including education, household income, and receiving health insurance from a spouse/partner. Given the conceptual relation between household income and the likelihood of experiencing job lock, we also conducted the regression analyses without income. The pattern of results remained the same. However, there is still the potential for SES-related factors to be affecting the results in the current study.

One of the strengths of this paper is that we conducted two separate studies to examine job lock. In Study 2, we sought to cross-validate our results with an independent sample. Although replication is often an important step with empirical research, we thought it was particularly important given important policy changes introduced in 2010 with the Affordable Care Act. Specifically, the ACA offers provisions for health insurance to provide affordable health insurance options to a larger number of Americans. Although the current study included a sample collected at the onset of the Affordable Care Act which was passed in 2010, open enrollment for the main parts of the legislation did not begin until October of 2013. As such, future research needs to examine whether the rates of job lock due to the need for health insurance have declined and whether declines are associated with better well-being outcomes.

With ongoing discussions about raising the ages for Social Security eligibility, findings from the current study suggest that there are potential negative consequences to life satisfaction for those adults experiencing job lock. Furthermore, results across Study 1 and Study 2 pointed to important differences in how perceived lock due to financial need and health insurance lock relate to other variables.

Theoretical Implications

In the current economic climate, job lock has become an increasingly important phenomenon (Huysse-Gaytandjieva et al., 2013; Wilkie et al., 2011). This was the first study to investigate job lock in relation to subjective well-being. First we gathered data to improve the conceptual clarity of job lock and then analyzed data from a large national panel study among two independent samples each assessed at two time points to increase our understanding of job lock in relation to work and well-being. This research contributes to retirement theory by integrating economic and psychological variables pertaining to work and the decision to leave one’s job or retire.

Results in this study are generally consistent with retirement theories describing decision making (e.g., rational choice and a resource-based perspective; Wang & Shultz, 2010). Following the resource-based perspective and rational choice theory, results of Study 2 suggested that those who reported job lock at Time 1 perceived that they did not have the resources to retire and were more likely to make the choice to stay at work despite their desire to retire. Thus the inconsistency between work status and job attitudes was related to lower life satisfaction two years later (i.e., at Time 2).

Examining data across two time points over approximately two years provided enough time for some participants to leave the workforce, which may have contributed to a change in psychological state as part of the retirement adjustment process. According to the resource-based perspective and rational choice theory, those who were locked at Time 1 but were then retired by Time 2 likely experienced a perceived gain in resources that allowed them to make the choice to retire. This gain would be perceived as positive and would lead to greater life satisfaction. Indeed, we found support for this insight. Likewise, participants also may have experienced an increase in perceptions of control over retirement which then aligned with their positive attitudes toward retirement, leading to increased life satisfaction. The negative relationship between job lock and well-being points to the importance of perceived control over one’s work situation. Results in this study are consistent with occupational health and social psychological literature that has demonstrated that the extent to which workers perceive control over their work situation is related to psychological well-being (van der Doef & Maes, 1999).

Practical Implications

The results of our study have implications for human resource management practices (de Lange, Kooij, & van der Heijden, 2015). In particular these results highlight the importance of human resource benefits (e.g., salary/wages and employer-provided health insurance) and workers’ perceptions of continuance organizational commitment to understanding preferences for retirement as well as life satisfaction. Organizations that would like to retain valued employees should offer attractive wage and health insurance benefits to employees. Results also suggest that firms should design jobs and work environments conducive to job satisfaction and other job attitudes. One method for reducing perceived job lock may be to offer satisfying work situations so that regardless of benefits, workers are satisfied, committed, and do not wish to leave the organization.

From a policy standpoint, there is substantial work capacity at older ages (Cutler, Meara, & Richards-Shubik, 2011; Weir, 2007). However, working longer may not be good for everyone (Fisher et al., 2015). Our results which showed the interaction between job lock, subsequent work status, and life satisfaction suggest that individuals’ well-being may improve post-retirement. Further research is also needed to evaluate the effectiveness of the Affordable Care Act. We suggest that evaluation should take psychological well-being into account as an important criterion for the health and well-being of older adults.

Limitations

Although this study was useful for relating job lock to other concepts, the study was not without limitations. First, although we conducted a screening study in MTurk in an effort to recruit a larger proportion of older workers, the obtained sample was still quite young (M = 35.4 years of age). As such, most of these workers may not have thought about leaving work altogether to retire, but perhaps for some other reason (e.g., for childbearing or family caregiving responsibilities). Attitudes toward work and other non-work roles may be different compared to an older worker population (i.e., at or nearing retirement age) and therefore future research should examine job lock and work attitudes among older workers, more comparable to those we studied in Sample 2. Secondly, the majority (91%) of participants reported job lock. As a result, there was little variance for testing the hypotheses in this study and the magnitude of the correlations we obtained may have been attenuated. It is likely that individuals in the younger MTurk sample are more apt to experience job lock, particularly due to money, compared to an older sample that may be more likely to have accumulated or saved adequate financial resources. They would also be more likely to feel locked due to a need for health insurance, as employer-provided health insurance plans may be more cost-effective or provide better coverage compared to health insurance available from the Affordable Care Act. Future research with an older sample may yield more variability for further examining the relations between job lock and other job attitudes.

Second, we did not examine all psychological constructs that may be related to job lock. For example, job embeddedness is another concept that is conceptually similar to organizational commitment and career entrenchment (Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski, & Erez, 2001). Future research should examine other such constructs in relation to job lock in an effort to further develop and understand the construct. Third, both job lock and life satisfaction in Study 2 were assessed with single-item measures. Although we were constrained by the data available in the HRS, this may have limited the reliability and validity of the results. Fourth, job lock in both studies was measured as a dichotomous variable –respondents answered “yes” or “no.” The measures used in the current study were consistent with Wilkie et al. (2011), but may limit the variability in perceptions of job lock compared to assessing the construct as a continuous variable. Lastly, results of this study likely do not generalize to populations of workers outside the U.S. The concept of job lock as assessed in this study is less relevant for individuals in countries with a mandatory retirement age and healthcare provided by the government.

Future Research

Because so little research has investigated job lock, there are many opportunities for future research. First, more research is needed to improve the conceptual clarity and measurement properties of job lock, including the use of Likert-type or other response scales to account for perceptions that may vary on a continuum. Additionally, research is warranted to further investigate the construct validity of job lock. This may be accomplished by conducting research to systematically examine antecedents (both person and job factors) and outcomes of job lock and whether job lock is a stable concept. This should include better understanding the psychological mechanisms by which perceptions of job lock are formed, which may involve social comparisons regarding pensions and retirement savings (Koposko, Kiso, Hershey, & Gerrans, 2016). Job lock research should be extended to consider how pension holdings, such as the extent to which having a pension plan and whether the type of pension (e.g., DB vs. DC), are related to perceptions of job lock.

In our paper we assessed workers’ perceptions of job lock at one point in time and then examined outcomes associated with perceptions of job lock. However, perceptions of job lock are likely not a discrete event. In other words, workers likely consider their circumstances and revisit the decision regarding whether to continue working or retire several times. Just as retirement is a process (Wang & Shultz, 2010), workers may re-consider or re-evaluate their subjective perceptions of job lock. Therefore additional longitudinal data are needed to understand intra-individual trajectories of well-being over time and to specifically examine the role of job lock in the retirement decision making and adjustment process.

Although our study examined job lock in relation to life satisfaction, future research should examine job lock in relation to other aspects of psychological well-being. For example, recent research has indicated that the meaningfulness of work is related to work and retirement behavior (Fasbender, Wang, Voltmer & Deller, 2016). Lastly, it would be interesting to relate workers’ experiences of job lock to bridge employment. In other words, are workers who experience job lock more likely to engage in bridge employment as part of the retirement process?

Summary and Conclusions

This study was an important first step toward examining the relation between job lock, an economic concept, in relation to workers’ job attitudes and well-being. Job lock, whether due to financial need or employer-provided health insurance need, is a highly prevalent phenomenon among workers in the U.S. Conceptually, job lock is related to continuance organizational commitment and career entrenchment. Our research demonstrated that job lock is related to life satisfaction among older adults. Results from three samples across two studies demonstrated distinct patterns for the two types of job lock. Therefore, future research should assess and evaluate financial job lock separately from insurance job lock. More research is needed to improve our understanding of the psychological measurement of job lock. Job lock seems to be an important issue related to work and well-being in the U.S. This paper advances our understanding of the retirement process to consider decisions regarding whether to continue working past the age of early eligibility for Social Security retirement benefits. This is particularly important, in light of changing healthcare policy and the U.S. Affordable Care Act.

Acknowledgments

Work on this project was partially supported by NIA U01AG009740 and 2011-06-2 by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. The authors would like to thank Hannes Zacher and other members of the Sloan Aging and Work Research Network for helpful suggestions on an earlier version of this paper.

Contributor Information

Gwenith G. Fisher, Colorado State University

Lindsay H. Ryan, University of Michigan

Amanda Sonnega, University of Michigan.

Megan N. Naudé, Colorado State University

References

- Allen NJ & Meyer JP (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63, 1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews FM, & Withey SB (1974). Developing measures of perceived life quality: Results from several national surveys. Social Indicators Research, 1, 1–26. doi: 10.1007/bf00286419 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S & Blau D (2013). Employment trends by age in the United States: Why are older workers different? Working paper WP 2013–285. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan Retirement Research Center. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2306610 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Farrell JL (2003). Beyond health and wealth: Attitudinal and other influences on retirement decision-making In Adams GA & Beehr TA (Eds.), Retirement: Reasons, processes, and results (pp. 159–187). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS (1976). The economic approach to human behavior. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beehr TA, Glazer S, Nielson NL, & Farmer SJ (2000). Work and nonwork predictors of employees’ retirement ages. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 57(2), 206–225. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1999.1736 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin KL, Pransky G, Savageau JA (2008). Factors associated with retirement related job lock in older workers with work related injury. Disability Rehabilitation, 30(26), 1976–1983. doi: 10.1080/09638280701772963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blau G (2001). Testing the discriminant validity of occupational entrenchment. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 74, 85–93. doi: 10.1348/096317901167244 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bloemen HG (2011). The effect of private wealth on the retirement rate: An empirical analysis. Economica, 78(312), 637–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0335.2010.00845.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle MA Lahey JN (2010). Health insurance and the labor supply decisions of older workers: Evidence from a U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Expansion, Journal of Public Economics, 94(7–8), 467–478. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradburn NM (1969). The structure of psychological well-being. Chicago, IL: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Burtless G & Quinn JF (2002). Is working longer the answer for an aging workforce? Center for Retirement Research Issue Brief #11, December. Chesnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. [Google Scholar]

- Bütler M, Huguenin O, & Teppa F (2004). What triggers early retirement? Results from Swiss pension funds. C.E.P.R. Discussion Paper No. 4394. Netherlands Central Bank, Research Department. [Google Scholar]

- Camman C, Fichman M, Jenkins D, & Klesh J (1979). The Michigan Organizational Effectiveness Questionnaire. Unpublished manuscript, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A, Converse PE, & Rodgers W (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Carson KD, Carson PP, & Bedeian AG (1995). Development and construct validation of a career entrenchment measure. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 68(4), 301–320. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1995.tb00589.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carson KD, & Carson PP (1997). Career entrenchment: A quiet march toward occupational death? The Academy of Management Executive, 11(1), 62–75. doi: 10.5465/ame.1997.9707100660 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carson KD, Carson PP, Phillips JS, & Roe CW (1996). A career entrenchment model: Theoretical development and empirical outcomes. Journal of Career Development, 22 273–286. doi: 10.1177/089484539602200405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chien S, Campbell N, Hurd M, Main M, Mallett J, Martin C, Meijer E, Miu A, Moldoff M, Rohwedder S, St.Clair P (2013). RAND HRS Data Documentation, Version M. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Center for the Study of Aging. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler NE (2014). Job lock and the Affordable Care Act. Journal of Financial Service Professionals, 68(4), 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler NE (2002). Job lock and financial planning: The impact of health insurance on the retirement decision. Journal of Financial Service Professionals, 56(6), 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler DM, Meara E, Richards-Shubik S (2011). Healthy life expectancy: Estimates and implications for retirement age policy. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, NB10–11, November. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- de Lange AH, Kooij DTAM, & van der Heijden BIJM (2015). Human resource management and sustainability at work across the life-span: An integral perspective In Truxillo D, Finkelstein L, Fraccaroli F, & Kanfer R (Eds.), Facing the challenges of a multi-age workforce: A use-inspired approach (pp.50–80). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, & Chan MY (2011). Happy people live longer: Subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 3(1), 1–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01045.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn D & Sousa-Poza A (2005). Early retirement: Free choice or forced decision? (CESifo Working Paper No. 1542). Munich, Germany: CESifo Group [Google Scholar]

- Fasbender U, Wang M, Voltmer JB, & Deller J (2016). The meaning of work for postretirement employment decisions. Work, Aging and Retirement, 2(1), 12–23. doi: 10.1093/workar/wav015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher GG, Chaffee DS, & Sonnega A (2016). Retirement timing: A review and recommendations for future research Work, Aging and Retirement. In press. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher GG, Matthews RA, & Gibbons AM (2016). Developing and investigating the use of single-item measures in organizational research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 21, 3–23. doi: 10.1037/a0039139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher GG, Ryan LH, & Sonnega A (2015). Prolonged working years: Consequences and directions for interventions In Vuori J, Blonk R, & Price RH (Eds.) Sustainable Working Lives: Managing Work Transitions and Health Throughout the Life Course (pp.269–288). Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg L (2007). The recent trend towards later retirement Center for Retirement Research Working Paper Series 9. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. [Google Scholar]

- Furunes T, Mykletun RJ, Solem PE, de Lange AH, Syse A, Schaufeli WB, & Ilmarinen J (2015). Late Career Decision-Making: A Qualitative Panel Study. Work, Aging and Retirement, 1(3), 284–295. doi: 10.1093/workar/wav011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman JK, Cryder CE, & Cheema A (2013). Data collection in a flat world: The strengths and weaknesses of Mechanical Turk samples. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 26(3), 213–224. doi: 10.1002/bdm.1753 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, & Madrian BC (2002). Health insurance, labor supply, and job mobility: A critical review of the literature (No. w8817). National Bureau of Economic Research. doi: 10.3386/w8817 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J & Madrian BC (2004). Health insurance, labor supply, and job mobility: A critical review of the literature In McLaughlin CG (Ed.), Health Policy and the Uninsured (pp. 97–178). Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gustman A, Mitchell O, & Steinmeier T (1994). The role of pensions in the labor market. A survey of the literature. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 47, 417–438. doi: 10.2307/2524975 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher CB (2003). The economics of the retirement decision In Adams GA & Beehr TA (Eds.), Retirement: Reasons, processes, and results. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]