Abstract

Background:

Aggressive end-of-life (EOL) care is associated with lower quality of life and greater regret about treatment decisions. Higher EOL costs are also associated with lower quality EOL care. Advance care planning (ACP) and goals-of-care (GOC) conversations (“EOL discussions”) may influence EOL healthcare utilization and costs among persons with cancer.

Objective:

To describe associations among EOL discussions, healthcare utilization and place of death, and costs in persons with advanced cancer; and explore variation in study measures.

Methods:

A systematic review was conducted using PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL. Twenty quantitative studies published January 2012 to January 2019 were included.

Results:

End-of-life discussions are associated with lower healthcare costs in the last 30 days of life (median $1,048 vs. $23,482; p < .001); lower likelihood of acute care at EOL [Odds Ratios (OR) ranging 0.43 to 0.69]; lower likelihood of intensive care at EOL (ORs ranging 0.26 to 0.68); lower odds of chemotherapy near death (ORs 0.41, 0.57); lower odds of emergency department use and shorter length of hospital stay; greater use of hospice (ORs ranging 1.79 to 6.88); and greater likelihood of death outside the hospital. Earlier EOL discussions (30+ days before death) are more strongly associated with less aggressive care outcomes than conversations occurring near death.

Conclusions:

End-of-life discussions are associated with less aggressive, less costly EOL care. Clinicians should initiate these discussions with cancer patients earlier to better align care with preferences.

Keywords: End-of-life, advance care planning, goals of care, communication, decision-making, costs, healthcare utilization, cancer, systematic review

Introduction

Aggressive, life-sustaining end-of-life (EOL) care is associated with lower quality of life,1 family perceptions of lower quality of care,2,3 and greater regret about treatment decisions.4 It is also more costly.5–7 In one study, cancer patients who received aggressive EOL care incurred 43% higher costs than patients who received non-aggressive care.8 High costs near EOL, which are a proxy for more acute care, are associated with worse quality of death6 and may contribute to patients’ financial toxicity, the financial burden and stress caused by cancer that is associated with myriad negative clinical and quality outcomes.9–13 High costs also create hardship for families, one-third of whom report spending all or most of their savings on costs related to their loved one’s terminal cancer care,14 and for health systems tasked with managing costs while providing high-quality care.15 Most importantly, costly aggressive care may not always reflect patient preferences.4 To better align care with preferences, the National Academy Medicine and American Society of Clinical Oncology recommend patients and providers have goals-of-care (GOC) conversations16 and that palliative care, which typically involves such discussions,15 be integrated into standard oncology care.17 These conversations may include discussions about patient values, prognosis, treatment options, aspects of living and dying, or specific interventions a patient may want if certain future conditions occur—all of which may occur in advance care planning (ACP).18 Interventions that include communication about ACP and care preferences have been found to improve concordance between care preferences and actual care delivered.19

Given that the costs of cancer care may vary by diagnosis, stage of disease, and treatment options;20 and that cancer disproportionately burdens racial minorities, who are often diagnosed at later stages when treatment may be very expensive,20,21 it is important to understand how care planning conversations are associated with healthcare utilization and costs among persons with advance-stage cancer, when utilization and costs may increase.20 Evidence suggests patient-provider discussions about EOL preferences are associated with less aggressive treatment near death6,22,23 and that interventions involving GOC discussions may reduce costs.24,25 Cancer is the second leading cause of mortality in the United States and globally,28,29 and one of the most expensive diseases to treat,30 in part due to rapid (often expensive) advances in cancer science that are adopted as standard of care. Although reviews of ACP and costs among older adults exist,26,27 variables and patient populations vary, limiting conclusions and warranting separate analysis among patients with cancer. The purpose of this review is to explore associations among ACP/GOC/EOL discussions, hereafter called “EOL discussions,” healthcare utilization, and costs among persons with advanced cancer (Stage III+) or persons who died of cancer. This review will also assess consistency and variation in how studies define EOL discussions and measure healthcare utilization outcomes.

Methods

Literature search strategy.

Authors used PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL databases to find studies conducted in the United States published from January 1, 2012 to January 8, 2019 that explored relationships between EOL discussions and financial costs, healthcare utilization, or place of death in adults with advanced cancer (see Table 1 for search terms). Because healthcare payment schemes differ by country, resulting in different costs and ways to measure costs, studies outside the United States were excluded. Qualitative studies, studies of children or adolescents, and studies presented at meetings or as abstracts were excluded. To enable comparability of costs and utilization near EOL, studies of patients with primarily early-stage cancer were excluded unless they focused on EOL care. The authors screened titles in search results and selected abstracts for review. Data extracted from each study were organized in a table of evidence summarizing key characteristics and study quality (Table 2). The review followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations.31 Two authors independently rated the quality of evidence using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine grading guide.32

Table 1.

Systematic Review search strategy in PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL

| Cancer terms | “Neoplasms”[mesh] OR cancer OR oncolog* |

| EOL terms | “end of life” OR end-of-life OR “terminal care”[mesh] OR end-stage OR advanced OR “stage III” OR “stage iv” OR terminal* |

| Communication terms | communicat* OR discuss* OR conversation* OR “advanc* care plan*” OR “advanc* directive*” OR “goals of care” OR polst OR “physician order for life sustaining treatment” |

| Financial terms | financ* OR “loss of income” OR “productivity loss” OR “economic burden*” OR “aggressive treatment” OR “aggressive care” OR “intensive care” OR ICU* OR “length of stay” OR “emergency room*” OR “emergency department” OR readmission* OR re-admission* OR readmi* OR hospice* OR cost* OR debt* OR bankrupt* OR “out of pocket” OR out-of-pocket OR “Cost of Illness”[Mesh] OR “personal cost*” OR “financial toxicity” OR expense* OR “financial burden” |

| Excluded terms | pediatric* OR paediatric* OR child* OR infan* OR neonat* OR newborn* OR adolescen* OR Britain OR Japan OR Uganda OR Korea OR Italy OR Ireland OR Australia[MeSH Terms] |

| Publication dates | January 2012- January 9, 2019 |

Table 2.

Table of Evidence for Studies Included in Systematic Review1

| Study | Study Design | Participants/Setting | Patient Characteristics | Intervention/ Comparator |

EOL Costs/Treatment Components Measured | Results |

Study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahluwalia et al., 201539 | Retrospective cohort study | 665 veterans with stage IV colorectal, lung, or pancreatic cancer. | 97.1% male, 74.7% white, mean age 66.4 years at time of diagnosis. 46.8% had care planning discussion within the first month of diagnosis. |

Documentation of a care planning discussion in the first month following diagnosis compared to no documentation of discussion. |

|

Lower likelihood to receive acute care at EOL (OR: 0.67l; p = 0.025), but not associated with less intensive interventions (OR: 0.74, p = 0.28), late chemotherapy (OR: 0.79, p = 0.35), or hospice use (OR: 0.75, p = 0.09). | 2b |

| Apostol et al., 201561 | Pilot cohort study | 86 hospitalized cancer patients at risk for critical care in an academic medical center. | GOC meeting vs. no GOC: Mean age 54 vs. 60 (p = 0.03); white 56% vs. 78% (p = 0.05); male 67% vs. 50%; solid tumor 59% vs. 71%. |

Patients with GOC meeting (reported by physician as having occurred recently or during the study hospitalization) compared to patients without. |

|

Less likely to receive critical care (use of continuous veno-venous hemofiltration dialysis and/or ventilation) (0% vs. 22%, p =0.003); more likely to be discharged to hospice (48% vs. 30%, p = 0.04). No statistical difference in readmissions, death during index hospitalization, or death within 30 days. | 4 |

| Cappell et al., 201835 | Retrospective cohort study | 422 patients who died after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) 2008–2015. | 42% female, 56% White. Patients with ADs were older (p < .0001) and more likely to be White (p = .0007). | Documentation and timing of AD (pre-HCT, during HCT (day of HCT to day 30), or post-HCT) |

|

Patients without AD were more likely to have ICU admission after HCT (52% vs. 41%, P = .03), within 30 days of death (40% versus 25%, P = .001), and within 2 weeks preceding death (36% versus 21%, P = .001); more likely to undergo mechanical ventilation (37% versus 21%, P = .0007); more likely to die in hospital and less likely to die on hospice. | 2b |

| Doll et al., 201336 | Retrospective cohort study | 84 gyn/onc patients near EOL discharged to hospice care after inpatient hospitalization | Hospice discussion group (HD, n = 15) vs. No-hospice discussion group (NHD, n = 69). Median age, 63 years. | Exposure to hospice discussion during the last outpatient clinical encounter prior to hospital admission. |

|

Decreased length of stay (3 days vs. 7 days, p = 0.008) and increased use of palliative care consultations during hospital stay (93.3% vs. 65.2%, p = 0.03). No significant difference in invasive procedures 4 weeks before hospitalization or chemotherapy 8 weeks before hospitalization. | 2b |

| Eckhert et al., 201734 | Single-center retrospective cohort study | 163 patients treated with HCT for a hematologic malignancy who died 2012–2015 | 53% male, 67% white; 34% multiple myeloma, 27% acute myeloid leukemia, 12% non-Hodgkin lymphoma. | Documentation of ACP—outpatient GOC, AD, POLST, and/or a code status of DNR/DNI > 30 days prior to death. |

|

More likely to die in hospice than in ICU (p = 0.001) or non-ICU acute care setting (p = 0.004). |

2b |

| Garrido et al., 201541 | Prospective cohort study with patient data and post-mortem caregiver interviews, 2002–2008. | 336 deceased patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers | Mean age, 58.3 years; 54.5% male; 62.2% white, 19.6% black, 16.7% Hispanic. |

ADs (based on preference for heroic or non-heroic EOL care) | Estimated costs of care received in the week before death based on average hospital expenditures, Medicare payment rates, and published estimates not actual costs. | ADs were associated with lower estimated costs in last week of life in adjusted models of patients who reported a preference for no heroic measures at EOL (adjusted mean incremental effect = $3082, standard error = $1395, p = 0.03) compared to patients who wanted heroic measures. | 2b |

| Garrido et al., 201642 | Prospective cohort study with post-mortem caregiver interviews, 2002–2008. | 311 patients with advanced cancer who died 2002–2008. |

Mean age, 59 years; 55% male; 61% white, 21% black, 17% nonwhite Hispanic | EOL discussion with a physician reported by patient during baseline interview | Costs of care estimated using reports of services (excluding chemotherapy) and place of death; based on average hospital expenditures, Medicare payment rates, and published estimates. | EOL discussion significantly associated with lower costs in last week of life in unadjusted generalized linear models (p=0.001), however cost data was not reported for this variable. |

2b |

| Gramling et al., 201848 | Multisite cohort study | 231 patients with metastatic cancer | 50% female; 13% African American, 8% Latino. | Discussion of length of life |

|

Increased likelihood of enrollment in hospice by 6-month follow-up (OR = 2.16; 95% CI = 1.25–3.73). | 2b |

| Hoerger et al., 201838 | Prospective cohort study (secondary analysis of randomized control trial data) | 171 patients diagnosed within 8 week with advanced lung or GI cancer who received early palliative care | Mean age of sample was 65.44 years. 88.9% of patients were white. | Monthly palliative care consultation involving advance care planning. |

|

Visits focused on treatment decisions associated with lower odds of new chemotherapy (OR, 0.57; p = .02) and hospital admission (OR, 0.62; P = .005) 60 days before death. Higher proportion of visits focused on ACP associated with higher odds of hospice (OR, 1.79; P = .03). | 2b |

| Loggers et al., 201343 | Multisite, prospective, cohort study | 292 self-reported Latino (n = 58) and White (n = 234) patients with Stage IV cancer | Hispanic vs. White populations: Mean age, 54.6 vs. 60.3 years (p = 0.01) |

Self-reported EOL discussion with doctor about wishes for care if patient were dying, by ethnicity (White and Latino) | Intensive EOL care, defined as resuscitation and/or ventilation followed by death in an ICU. | No White or Hispanic patient who reported having EOL discussion at baseline received intensive EOL care. No difference in intensive EOL care among Latino and White patients with EOL discussion (p = 0.11). | 2b |

| Lopez-Acevedo et al., 20131 | Retrospective cohort study | 220 women who died of advanced ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer diagnosed between 1999 and 2008, and treated by a gynecologic oncologist. | Mean age, 61.2 years; 76% Caucasian, 21% African American; 87% ovarian cancer, 13% primary peritoneal cancer; 52% hospitalized in the last month; 62% had invasive procedures in the last 6 months of life, 35% had invasive procedures in the last month of life. | Documented EOL discussion with healthcare provider ≥ 30 days before death vs. < 30 days before death, defined as discussion with patient during which DNR status/resuscitation, comfort care (i.e., transition from extending life to focusing on improving EOL symptoms and experience), or hospice care was mentioned. | Chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life, >1 hospitalization in the last 30 days of life, >1 ER visit in the last 30 days of life, ICU admission in the last 30 days of life, dying in an acute care setting, admission to hospice ≤ 3 days | EOL discussion ≥ 30 days before death associated with lower incidence of: chemotherapy in last 14 days of life (p = 0.003); >1 hospitalization in last 30 days of life (p <0.001); ICU in last 30 days of life (3% vs. 16%, p = 0.005); dying in acute care setting (p = 0.01); hospice initiated ≤ 3 days before death (p = 0.02), or any EOL quality measure (listed here) (p <0.001); lower likelihood of hospitalization in last month of life (p < 0.001) and in-hospital death (p < 0.001); fewer invasive procedures in last month of life (p < 0.001); and longer hospice enrollment (53 vs. 11 days, p < 0.001). |

4 |

| Mack et al., 201223 | Prospective cohort study |

1,231 patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium who died during the 15-month study period but survived at least 1 month. |

62% male; 76% non-Hispanic white, 12% non-Hispanic black, 5% Hispanic, 4% Asian; 61% married/living as married; 14% age 21–54, 25% age 55–64, 34% age 65–74, 27% 75+; 18% college degree or greater; 82% lung cancer, 18% colorectal cancer. |

EOL discussions, identified via: a) Patient or surrogate report of a discussion with the physician about resuscitation or hospice care; b) Medical record documentation of a discussion about advance care planning or venue for dying. |

|

Patients with EOL discussions less likely to have chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life (OR 0.41, p < 0.001), acute care in the last 30 days of life (OR 0.43, p < 0.001), or any aggressive care in last 30 days of life (OR 0.40, p < 0.001); more likely to have hospice care (OR 6.88, p < 0.001). No association found between EOL discussion and ICU care in last 30 days of life (p = 0.55). Patients with EOL discussion > 30 days before death less likely to receive aggressive EOL care (p < 0.001), acute care in last 30 days of life (p < 0.001), chemotherapy in last 14 days of life (p =0.003), and hospice 7 days before death (p < 0.001); more likely to have hospice (p < 0.001). ICU care in last 30 days of life insignificant (p = 0.16). | 2b |

| Marcia et al., 201849 | Retrospective cohort study | 203 patients with stage IV cancer referred to acute care surgical service 2009–2016 | Mean age 55. 51% female, 12% White, 43% Hispanic, 28% Black. 27% colon cancer. | Documentation and timing of AD |

|

Patients who completed AD (including DNR status) post-admission had longer hospital lengths of stay (P < 0.001) and ICU lengths of stay (P< 0.001) compared to patients who continued full-code status throughout hospitalization and patients with a DNR on-admission. | 4 |

| O’Connor et al., 201562 | Retrospective cohort study | 182 patients who died of metastatic breast cancer and eligible for hospice 1999 to 2010. | Hospice vs. Nonhospice differences: ≤ high school education, 14% in hospice group vs. 31% in non-hospice group, p = 0.02. | Documentation of an advance directive discussion with oncology team |

|

Patients admitted to hospice more likely to have AD discussion documented (p < 0.001) and discussion of palliative care (p<0.001) than patients who died without hospice. Place of death was associated with hospice utilization (p < 0.001). | 2b |

| Patel et al., 201850 | Randomized clinical trial (retrospective analysis of randomized quality improvement study) | 213 veterans with Stage III or IV or recurrent cancer planning to receive care 2013 – 2015. | Mean age 69 years; 99% male. 78% non-Hispanic White, 5% Black, 3% Asian/Pacific Islander, 2% Hispanic. | Documentation of GOC/EOL preferences by oncology clinician within 6 months of randomization. Intervention: 6-month structured program where lay health worker assisted patients with ACP, including GOC, care preferences, choosing a surrogate decision maker, discussing AD, encouraging GOC discussion with providers. |

|

Patients in intervention group who died had fewer ED visits (P < .001) and fewer hospitalizations (P < .001), were more likely to receive hospice care (P = .002), and had lower health care costs within 30 days of death (median [interquartile range], $1048 [$331-$8522] vs $23 482 [$9708-$55 648]; P < .001) than patients in the control group who died. Patients in intervention group more likely to have used hospice within 6 and 15 months of randomization (P = .006; P = .009, respectively). | 1b |

| Pedraza et al., 201754 | Retrospective cohort study | 2,159 West Virginians with ADs and/or POLST who died of cancer 2011–2016. | Lung (28%), colorectal (9%), pancreatic (6%), breast (6%), prostate (3%), other (48%) cancers. | Use of POLST vs AD | Out-of-hospital death (OHD) and hospice admission | OHD 85.7% for patients with POLST, 72.0% for ADs (p < .001); hospice admission 49.9% for POLST, 27.0% for ADs (p < .001). | 4 |

| Rocque et al., 201745 | Convergent, parallel mixed method design to evaluate implementation of navigator-led ACP across 12 cancer centers | 2,752 deceased patients with cancer; 437 patients completed or were in the process of completing the lay Patient Care Connect Program (PCCP). | Group that completed or started the PCCP program: 56% male, 79.9% white, 51.7% high acuity. | Completion or involvement in program with ACP discussions vs. no involvement in program/discussion. |

|

Patients who started or completed ACP discussion with a navigator had lower hospitalization rates within 30 days of death (46% vs. 56%, p = 0.02), but not within last 14 days of life (36% vs. 44%, p = 0.09). PCCP patients had lower ER rates within 14 days of death (33% vs. 42%, p = 0.04). | 2b |

| Sharma et al., 201546 | Multisite, prospective cohort study with chart review and interviews of caregivers to identify ICU stay in the last week of life. | 353 terminally ill patients with metastatic cancer interviewed before death, and their caregivers, from six comprehensive cancer centers. | Mean age 58 years; 54% male; 64% white, 19% black, 16% Hispanic; 23% lung cancer, 34% GI cancer, 12% breast cancer, 32% other cancer. | Self-reported recollection of EOL discussion with doctor (wishes about care patient would like to receive when dying); by gender. |

|

Patients who had ICU care at EOL less likely to report EOL discussion with doctor (19% vs. 38%, p = 0.02) than patients who did not receive EOL ICU care. Men with EOL discussion less likely to have ICU care at EOL than men without EOL discussion (odds ratio, 0.26; p = 0.04); no difference in EOL ICU for women based on EOL discussion (p = 0.4). | 2b |

| Zakhour et al., 201537 | Retrospective cohort study | 136 patients who died of invasive gynecologic malignancies 2010–2012 |

Median age at death, 70 years; 79% White, 11% African American; 91% advanced stage (III/IV); 71% documented EOL discussion; 52% documented AD at death. 81% had EOL discussion in inpatient setting,. | EOL discussion (GOC for EOL, hospice or palliative care, code status) or completion of AD or POLST (hereafter called “EOL discussion”) >30 days before death |

|

Compared to patients who had late or no EOL discussion before death, patients with earlier discussions less likely to have inpatient admission (p = 0.001) in last 30 days of life; more likely to have hospice (p=0.001) and more days in hospice (p < 0.001), less likely to be non-compliant with ≥1 National Quality Forum (NQF) overutilization measures (12% vs. 38%, p = 0.005) Compared to patients with inpatient EOL discussion, patients with first discussion outpatient less likely to die in hospital (0% vs. 34%, p = 0.001) or have ICU care in last 30 days of life (p = 0.06). |

4 |

| Zaros et al., 201347 | Retrospective cohort study | 115 adult patients with advanced cancer who were documented to have decisional capacity upon admission and died in the hospital. | 52% age > 65 years; 59% male; cancer type 37% lung, 30% bone marrow, 7% esophagus, 6% pancreatic, 5% liver, 5% colon, 10% other | Patients who participated in EOL discussion vs. patients who lost decisional capacity after admission and had surrogate participate in EOL discussion | Utilization during terminal admission:

|

Patients who had EOL conversations themselves, compared to patients with surrogates, were less likely to receive ventilator support (23.2% vs. 56.5%, p < 0.01); artificial nutrition or hydration (25% vs. 45.7%, p = 0.03); chemotherapy (5.4% vs. 39.1%, p < 0.01); antibiotics (78.6% vs. 97.8%, p < 0.01); ICU treatment (23.2% vs. 56.5%, p < 0.01); had shorter length of hospitalization (mean 15.8 days vs. 10.3 days, p = 0.03). | 4 |

EOL is end-of-life; ACP is advanced care planning; GOC is goals-of-care (conversation); AD is advance directive; POLST is physician order for life sustaining treatment; POST is physician order for scope of treatment; DNR is do not resuscitate; DNI is do not intubate; CPR is cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CI is confidence interval; SD is standard deviation. The quality of each study was assessed following the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine quality rating scheme.

Results

Literature search.

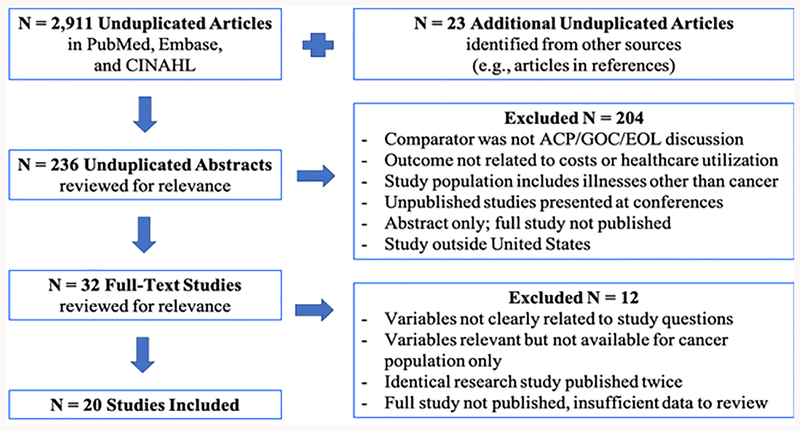

Systematic searches resulted in 2,911 unduplicated articles. Twenty-three additional articles were identified through references and search engine recommendations (Figure 1). After identifying relevant titles in each database and importing those listings into EndNote software, 236 unduplicated abstracts were reviewed. Based on review criteria, 20 studies were included.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram showing systematic review screening and inclusion process, adapted from Moher and colleagues31

Description of studies.

Included studies were conducted with populations predominantly composed of patients with Stage III or IV cancer, or patients who recently died from cancer. Cancer types included breast,33 hematological,34,35 gynecological,1,36,37 lung or GI,38 and any type.23,39–50 Sample sizes ranged from 84 to 2,752 participants, with a median of 226 participants per study. Two studies featured fewer than 100 participants.36,40 All studies were conducted in the United States. Settings varied and included for-profit, not-for-profit, and government institutions. Some hospital-based studies incorporated data from outpatient care. The studies’ comparator was an EOL discussion, defined as any conversation about EOL goals or treatment preferences with a healthcare provider or trained facilitator, documented in medical records or self-reported by patients or surrogates, or described as ACP, which sometimes includes advance directives (AD), physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST), or do-not-resuscitate (DNR) or do-not-intubate (DNI) orders that suggest discussion about preferences. Because ADs, POLSTs, and DNR documentation may be associated with preference for treatment limitations,41,51 results of studies that exclusively or predominantly assessed ADs, POLSTs, or DNR were differentiated. Three studies examined EOL costs using either EOL discussion or a proxy such as AD as comparator.41,42,50 No studies examined the impact of out-of-pocket costs on patients. Eighteen studies assessed relationships between EOL discussions and healthcare utilization near death1,23,33,35–38,40,43–50,52 and six studies assessed place of death.1,33–35,37,44 In addition, six studies incorporated elements of time in their assessment of EOL discussions, generally referring to these discussions as early (31+ days before death) or late (within 30 days of death), with later conversations typically occurring in inpatient settings.1,23,39,47,49

Quality of studies.

To assess study quality, two authors (L.T.S. and K.L.C.) independently used the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine Levels of Evidence grading guide.32 Independent ratings were then compared. Disagreements on ratings (10% of studies) were resolved by further analyzing study methodology. One study was a retrospective analysis of a randomized clinical trial (RCT);50 one study was non-randomized, intervention-based;45 and 18 studies were observational.1,23,33,35–38,40–44,46–49,52,53 Strengths of the studies included clearly-stated objectives and inclusion criteria, sample sizes adequate for meeting objectives, and well-defined outcomes and variables (Table 2). Study limitations included prevalence of retrospective cohort design; variation among independent variable measurement, with some studies assessing EOL discussions based on self-report and others based on medical chart review; diversity in outcomes measured; and small sample size for two studies,36,40 limiting power and analysis (Table 2). Six studies received lower ratings because they did not account for confounders.1,37,40,44,47,49

Summary of Findings

EOL discussion associated with lower EOL costs.

Only three studies (two from the same dataset) measured costs,41,42,50 but one of these studies was a high-quality RCT.50 In their RCT, Patel and colleagues found patients with advanced cancer who received a six-month program to discuss and document EOL preferences with a trained lay health worker, and who later died (n=120), had lower total healthcare costs within 30 days of death (median [interquartile range], $1,048 [$331-$8,522] vs. $23,482 [$9,708-$55,648]; p < .001) than patients in the control group who died.50 Fifteen months after randomization, total healthcare costs among the entire study population were lower in the intervention group, but the difference was not statistically significant (median [interquartile range], $86,025 [$63,255-$133,256] vs. $111,958 [$75,803-$171,025]; p = .08).50

The two studies by Garrido and colleagues41,42 are limited in their applicability due to how authors defined and used EOL communications as variables. In their 2015 study, the authors assessed costs in the last week of life in terms of preferences for heroic treatment or no heroic treatment, as documented in ADs.41 As expected, costs were lower among patients who reported a preference for no heroic measures at EOL (adjusted mean incremental effect = - $3,082, p = 0.03) compared to patients who preferred heroic measures.41 Because AD completion was associated with a difference in EOL care preferences, the authors’ results may be biased toward lower costs, limiting comparison to the RCT by Patel and colleagues. The other study by Garrido and colleagues claimed a self-reported EOL discussion with a doctor about EOL care preferences was significantly associated with costs in the last week of life (p = 0.001), but failed to provide cost data, limiting comparison.42

EOL discussion associated with less acute care near EOL.

Despite variations in discussion comparators, we found each study in the review identified some, if not many, significant associations between EOL discussion and either lower costs near EOL,41,42,50 lower utilization of high cost care such as acute or intensive care,1,36–40,43,46,47,50 or reduced use or duration of hospital services.1,36,38,45,47,49,50 Studies of EOL or GOC discussions not involving ADs or POLST found associations between these discussions and a lower likelihood of having acute care in the last 30 days of life [Odds Ratios (OR) ranging 0.43 to 0.69)23,39,45,50 and a lower likelihood of receiving ICU care in the last 30 days of life (ORs 0.26 and 0.68),45,46 with insignificant results suggesting trends toward lower utilization. Patients who complete ADs may be more likely to prefer less intensive EOL care,41 but Cappell and colleagues (n=422) found similar odds: patients with an AD were similarly less likely to receive ICU care within 30 days of death (25% vs. 40%, OR 0.49, p = 0.001) than patients without ADs.35

Studies did not consistently measure readmission rates, emergency department visits, or length of stay, although those that did often found associations with reduced rates.36,45,47,50 For example, Rocque and colleagues (n = 2,752) found patients who started or completed an ACP discussion about care goals and preferences with a lay facilitator trained in the Respecting Choices method had lower hospitalization rates within 30 days of death (46% vs. 56%, p = 0.02) and that patients with ACP discussions had lower Emergency Department (ED) visit rates within 14 days of death (33% vs. 42%, p = 0.04).45 In their RCT, Patel and colleagues found patients who received a structured ACP program involving GOC or care preference discussion before death were also less likely to visit the ED (5% vs. 45%, p < 0.001) or be hospitalized (5% vs. 43%, p < 0.001) in the last 30 days of life compared to the control group (n = 120 total deceased patients), and had fewer mean ED visits (p < 0.001) and fewer mean admissions (p < 0.001) in the last 30 days of life.50 Hoerger and colleagues (n = 125 deceased patients) similarly found that palliative care visits to discuss treatment decisions were associated with a lower odds of hospitalization within the last 60 days of life (OR 0.62, p = .005).38 In total, four studies found evidence of reduced hospital length of stay (LOS), as well.36,47,49,50

The six studies that assessed place of death found associations between EOL discussion and death outside a hospital, but generally used mixed definitions of ACP as the comparator.1,33–35,37,44 Eckhert and colleagues (n = 163), who broadly defined an EOL discussion as an outpatient GOC discussion, AD, POLST, or DNR/DNI more than 30 days before death, found patients with ACP were more likely to die in hospice than the ICU (p = 0.001) or in a non-ICU acute care setting (p = 0.004).34 Conceptualizing EOL discussion to also include ACP, GOC, and discussion proxies such as POLSTs and ADs, Zakhour and colleagues (n = 136) found patients who had a discussion inpatient had much higher odds of dying in the hospital than patients who had a discussion outpatient (34% vs. 0%, OR 20.5, 95% CI, 1.19 to 352.6, p = 0.04), providing context to possible relationships between discussion location and place of death.37 In this study, 70% of patients had a GOC discussion, suggesting the findings may compare to studies with GOC as a comparator.37 Studies that assessed place of death among patients who had ADs or POLST found similar results. For example, Cappell and colleagues found patients with ADs were less likely to die in the ICU and more likely to die at home (p = 0.003).35 Pedraza and colleagues (n = 2,159) found the odds of dying outside the hospital were more than two times greater for patients with POLSTs than patients with ADs (OR 2.3, p < 0.001).54

Of the 11 studies that assessed hospice use, nine studies found significant associations with EOL discussions (ORs ranging 1.79 to 6.88).23,33,34,37,38,40,44,48 Findings were strongest among studies that defined discussions based on EOL, GOC, and treatment preference conversations.23,33,38,40,48 Among patients who died during the RCT (n = 120), for example, Patel and colleagues found an GOC intervention was associated with higher rates of hospice use (48% vs. 77%, p = 0.002; OR 3.51, 95% CI 1.6–7.69, p = 0.002).50 Mack and colleagues (n = 1,231) also found patients who had EOL discussions were much more likely to receive hospice care (OR 6.88, 95% CI 4.36–10.8, p<0.001),23 as did Gramling and colleagues (n = 231), who found patients engaged in a length-of-life discussion were more likely to enroll in hospice by six-month follow-up (OR = 2.16; 95% CI 1.25–3.73).48 The two studies that defined EOL discussions based on a mix of GOC, ADs, and POLST use also found significant results.34,37 Zakhour and colleagues, for example, found patients who had a conversation involving GOC, AD, or POLST 31+ days before death were more likely to have higher rates of hospice (p = 0.001) and more days in hospice (p < 0.001).37 Adding context to these findings, Pedraza and colleagues found patients with POLST were more likely than patients with ADs to enroll in hospice (OR 2.69, 95% CI 2.25 to 3.22, p < 0.0001).44 Two other studies that measured hospice use did not find significant results.39,45

Associations between EOL discussion and chemotherapy use near EOL were mixed. For example, Mack and colleagues (n = 1,231) found patients who had EOL discussions were less likely to have chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life (OR 0.41, p < 0.001)23 and Hoerger and colleagues (n = 171) found palliative care visits that addressed treatment decisions were associated with lower odds of a patient receiving new chemotherapy within 60 days of death (OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.90, p =0.02).38 However, Ahluwalia and colleagues (n = 665), who defined EOL discussion as any documented care planning discussion in the first month following cancer diagnosis among veterans, did not find an association between discussion and chemotherapy near death (OR: 0.79, p = 0.35).39 With or without an EOL discussion, Garrido and colleagues found baseline chemotherapy (median 3.5 months before death) was significantly associated with higher costs of care in the last week of life.42 Studies of AD or POLST use did not assess late chemotherapy as an outcome.35,44

Earlier EOL discussion associated with stronger outcomes.

Finally, the six studies that explored associations between EOL communications and care-related outcomes in the context of time identified significant associations.1,23,37,39,47,49 Of the studies that exclusively looked at EOL discussions not AD or POLST documentation, earlier conversations (defined as occurring 30–31 days or more before death, typically in inpatient settings) were found to be associated with lower likelihood of receiving any aggressive care in the last 30 days or life (ORs ranged 0.10 to 0.34),1,23 lower likelihood of receiving acute care in the last 30 days of life (ORs ranged 0.03 to 0.67),1,23,39 lower likelihood of ICU care in the last 30 days of life (ORs ranged 0.19 to 0.33),1,23 and greater likelihood of enrollment in hospice care (OR 2.8, 95% CI 2.06 to 3.75, p< 0.001).23

Some studies did not find significant associations between the timing of EOL discussions and hospice care or did not measure hospice enrollment overall but did measure time between hospice enrollment and death. Lopez-Acevedo and colleagues, for example, found early EOL discussions were associated with significantly more days of hospice care before death (median length of enrollment 53 days vs. 11 days, p < 0.001) and a lower likelihood of late enrollment in hospice within three days of death (OR 0.16, p = 0.02).1 Zakhour and colleagues, whose sample predominantly engaged in GOC discussions but also may have completed ADs or POLST, found patients who had late EOL discussions were eight times as likely to either enroll in hospice within three days of death or not enroll at all (OR 8.0, 95% CI 3.3–19.2, p < 0.0001) than those who had an early conversation.37 Earlier conversations were also associated with a much greater likelihood of patients dying outside the hospital (OR 8.9, p = 0.0001) compared to late conversations.1

Variation in conceptualization of EOL discussions.

We found wide variation in how studies defined EOL discussions. Most studies based EOL discussions on documentation in the medical record or patient/surrogate reports of an EOL conversation with a healthcare provider; and others defined ACP in terms of documentation of medical orders such as DNR/DNI, POLST, AD, or living will. Some studies conceptualized EOL communication as a mix of terms. Eckert and colleagues, for example, defined ACP as documentation of an outpatient GOC conversation, AD or POLST, and/or DNR/DNI code status.34 Professional health providers led most discussions, though two studies featured professionally-trained lay healthcare workers, reflecting trends to train both lay workers and a growing body of primary palliative care providers.45,50 The wide variation in how clinicians and researchers define EOL discussions makes comparison difficult.

Variation in healthcare utilization outcomes.

We also found wide variation in EOL healthcare utilization outcomes measured. These measures serve as proxies for costs, but also represent variance in how clinicians conceptualize aggressive care and overuse of healthcare services near EOL. For example, Loggers and colleagues defined intensive EOL care as resuscitation and/or ventilation in the last week of life followed by death in the ICU or hospice,43 whereas Ahluwalia and colleagues defined an intensive intervention as any of the following occurring in the last 30 days of life: an ICU admission, new hemodialysis, placement of a gastric tube, new mechanical ventilation, or death despite attempts at cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).39 Furthermore, Mack and colleagues measured ICU care in the last 30 days or life, but also grouped measures into a category called “aggressive care” that included any ICU care or acute care in the last 30 days of life, or chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life.23 Similar variations in conceptualizing or grouping measures were common across studies, making clean comparisons difficult. These findings suggest a lack of standardization in what may represent unnecessary care near EOL.

Discussion

This systematic review evaluated the relationship between EOL discussions about care planning and EOL costs, healthcare utilization, and place of death in persons with advanced cancer. The 20 included studies provide evidence that an EOL discussion is associated with less costly and less aggressive or intensive forms of care near EOL, and greater use of hospice services; and that relationships are even stronger when conversations occur 30 days or more before death. Findings were similar for studies that assessed proxies for EOL discussion such as ADs, POLST, and DNR orders. The implications of these findings are significant.

First, it appears patient-provider EOL discussions influence patients’ decisions to receive less aggressive, less costly care at EOL, possibly due to a patient’s increased knowledge and understanding of their illness and care options. Because less aggressive, less costly EOL care is associated with numerous quality outcomes,1–4,55 EOL discussions about care preferences may help improve the EOL experience for patients and families.3 To improve the EOL experience, clinicians should routinely have these conversations with cancer patients—and in a timely matter, not just in the weeks or days before death. For patients with cancer who are hospitalized, it is critical that clinicians initiate these discussions early in the hospital stay.

Although none of the studies assessed EOL costs or healthcare utilization by race, some studies did find evidence that racial minorities were less likely than Whites to have these important EOL discussions with their healthcare providers,23,40 a finding that is consistent with the literature.56–58 For example, Mack and colleagues found that compared to White patients, Black/African American patients (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.73) and Hispanic patients (OR 0.29, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.73) were less likely to experience EOL discussions (p = 0.005).23 Clinicians should initiate EOL discussions with all their patients, especially racial and ethnic minorities who may be less likely to have these conversations.

As part of EOL care planning, clinicians may also consider discussing patients’ financial wellbeing and the estimated costs of treatment options—not to make clinical decisions based on costs, but to acknowledge the financial burden cancer care has on patients and families, and support informed decision-making. A majority of cancer patients report some desire to discuss treatment-related out-of-pocket costs with their care team, but less than 20% of patients actually discuss costs with their doctors.59 In the study by Apostol and colleagues, the need patients reported providers most poorly met in GOC conversations was the need for more economic and insurance information related to cancer,40 further supporting the idea that such conversations matter. The high cost of cancer care is associated with decreased quality of life and increased risk of mortality and morbidity,9–11 making it a clinical and ethical concern.

End-of-life discussions also influence hospital and payer costs. One recent study found palliative care consultations for GOC/EOL were associated with a decrease in future acute care utilization, reducing future costs by more than $6,000 per patient.15 Although EOL discussions should never be used to deny necessary care, hospitals and payers may benefit from patients choosing less costly forms of care when consistent with patient goals. Finally, this review highlights the need for more research about EOL communication and costs, the timing of discussions, and racial/ethnic disparities across such measures. Standardization of outcome measurement and greater consistency in definition of outcomes is recommended.

This review has several limitations. First, only one study tested causal relationships through an RCT.50 This study was also the only study to assess associations among EOL discussions for GOC and costs;50 the other two cost studies compared AD utilization or did not adequately provide cost data.41,42 Third, studies did not account for the same utilization variables, consistently define the variables, or collect data on variables the same way. Studies that used self-report to measure EOL conversations could not account for recall bias, while studies using medical records could not account for undocumented conversations. Fourth, variation in healthcare utilization variables limits study comparison. Finally, studies captured results in different cancer populations and healthcare systems that have varying levels of efficiency, rates of intensive care at EOL, training in EOL communications, and resources.39 These differences may limit generalizability of results. Despite these limitations, this review provides clinical insights that may help improve EOL care for persons with cancer and justify investment in EOL communication interventions.

Ethical Considerations

This review provides preliminary evidence that EOL discussions may reduce costs and utilization of aggressive EOL care. Reducing costs should not be a driving reason for engaging patients in EOL discussions.60 Instead, clinicians and payers should consider EOL discussions an intervention that uniquely increases patient autonomy, improves quality of care and quality of death, and saves resources at the same time.25 When communication is improved, better quality results and lower costs tend to follow, mutually benefitting patients and systems and further strengthening the case for EOL discussions.

Conclusions

End-of-life discussions are associated with lower EOL costs, less acute and aggressive care, less time spent hospitalized, greater use of hospice, and greater odds of dying outside the hospital—all outcomes associated with greater quality of life and quality of care. Separately, ADs and POLST documentation are similarly associated with reductions in intensive care at EOL. Earlier discussions about care goals give patients with advanced cancer more time to make informed decisions and result in higher quality EOL care that happens to be less costly. Clinicians should initiate EOL discussions with patients earlier to support patient-centered care and enable informed decision-making. More standardized research is needed to better understand relationships between these important discussions, healthcare utilization, and costs.

Acknowledgments and Conflicts of Interest:

LTS acknowledges support from the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award training program in Individualized Care for At Risk Older Adults at the University of Pennsylvania, National Institute of Nursing Research T32NR009356; the Rita and Alex Hillman Foundation’s Hillman Scholars Program; Jonas Philanthropies’ Jonas Nurse Leaders Scholars program; and the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania. KLC acknowledges support from the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award training program in Individualized Care for At Risk Older Adults at the University of Pennsylvania, National Institute of Nursing Research T32NR009356. SHM and CMU declare they have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to report.

Contributor Information

Lauren T. Starr, Predoctoral Fellow in Nursing, NewCourtland Center for Transitions and Health, Masters in Bioethics candidate, Penn Center for Bioethics, Associate Fellow, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania.

Connie M. Ulrich, Lillian S. Brunner Chair in Medical and Surgical Nursing, Professor of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, Professor of Bioethics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

Kristin L. Corey, Postdoctoral Fellow, NewCourtland Center for Transitions and Health, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing.

Salimah H. Meghani, Associate Professor of Nursing, Term Chair of Palliative Care, Senior Fellow, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania.

References

- 1.Lopez-Acevedo M, Havrilesky LJ, Broadwater G, et al. Timing of end-of-life care discussion with performance on end-of-life quality indicators in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130(1):156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL. Quality of End-of-Life Care Provided to Patients With Different Serious Illnesses. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1095–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gieniusz M, Nunes R, Saha V, Renson A, Schubert F, Carey J. Earlier Goals of Care Discussions in Hospitalized Terminally Ill Patients and the Quality of End-of-Life Care: A Retrospective Study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(1):21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith-Howell ER, Hickman SE, Meghani SH, Perkins SM, Rawl SM. End-of-Life Decision Making and Communication of Bereaved Family Members of African Americans with Serious Illness. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2016;19(2):174–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chastek B, Harley C, Kallich J, Newcomer L, Paoli CJ, Teitelbaum AH. Health care costs for patients with cancer at the end of life. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(6):75s–80s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):480–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Z O, M M, S A, F D, S B, C DM. Association between the Medicare hospice benefit and health care utilization and costs for patients with poor-prognosis cancer. JAMA. 2014;312(18):1888–1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheung MC, Earle CC, Rangrej J, et al. Impact of aggressive management and palliative care on cancer costs in the final month of life. Cancer. 2015;121(18):3307–3315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18(4):381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(6):1143–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arozullah AM, Calhoun EA, Wolf M, et al. The financial burden of cancer: estimates from a study of insured women with breast cancer. J Support Oncol. 2004;2(3):271–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharp LCA, Timmons A. Associations between cancer-related financial stress and strain and psychological well-being among individuals living with cancer. . Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22(4):745–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon LG, Merollini KMD, Lowe A, Chan RJ. A Systematic Review of Financial Toxicity Among Cancer Survivors: We Can’t Pay the Co-Pay. Patient. 2017;10(3):295–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cagle JG, Carr DC, Hong S, Zimmerman S. Financial burden among US households affected by cancer at the end of life. Psychooncology. 2016;25(8):919–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Connor NR, Junker P, Appel SM, Stetson RL, Rohrbach J, Meghani SH. Palliative Care Consultation for Goals of Care and Future Acute Care Costs: A Propensity-Matched Study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017:1049909117743475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.IOM IoM. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life Washington, DC: IOM; 2015. March 19 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(1):96–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulman-Green D, Smith CB, Lin JJ, Feder S, Bickell NA. Oncologists’ and patients’ perceptions of initial, intermediate, and final goals of care conversations. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Houben CHM, Spruit MA, Groenen MTJ, Wouters EFM, Janssen DJA. Efficacy of advance care planning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(7):477–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaye DR, Min HS, Herrel LA, Dupree JM, Ellimoottil C, Miller DC. Costs of Cancer Care Across the Disease Continuum. Oncologist. 2018;23(7):798–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haynes MA, Smedley BD. The Unequal Burden of Cancer: An Assessment of NIH Research and Programs for Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved In: Haynes MA, Smedley BD, eds. The Unequal Burden of Cancer: An Assessment of NIH Research and Programs for Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved. Washington (DC): Institute of Medicine, NIH; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernacki RE, Block SD, American College of Physicians High Value Care Task F. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1994–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: a prospective cohort study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(35):4387–4395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dalal S, Bruera E. End-of-Life Care Matters: Palliative Cancer Care Results in Better Care and Lower Costs. Oncologist. 2017;22(4):361–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klingler C, in der Schmitten J, Marckmann G. Does facilitated Advance Care Planning reduce the costs of care near the end of life? Systematic review and ethical considerations. Palliat Med. 2016;30(5):423–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jimenez G, Tan WS, Virk AK, Low CK, Car J, Ho AHY. Overview of Systematic Reviews of Advance Care Planning: Summary of Evidence and Global Lessons. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(3):436–459 e425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weathers E, O’Caoimh R, Cornally N, et al. Advance care planning: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials conducted with older adults. Maturitas. 2016;91:101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Organization WH. Cancer. 2019; https://www.who.int/cancer/en/.

- 29.Health NIo. Cancer Statistics. 2019; https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/statistics.

- 30.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, Part I: a new name for a growing problem. Oncology (Williston Park). 2013;27(2):80–81, 149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medicine OCfE-b. Levels of Evidence-1. 2009; https://www.cebm.net/2009/06/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/.

- 33.O’Connor TL, Ngamphaiboon N, Groman A, et al. Hospice utilization and end-of-life care in metastatic breast cancer patients at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(1):50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eckhert EE, Schoenbeck KL, Galligan D, McNey LM, Hwang J, Mannis GN. Advance care planning and end-of-life care for patients with hematologic malignancies who die after hematopoietic cell transplant. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2017;52(6):929–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cappell K, Sundaram V, Park A, et al. Advance Directive Utilization Is Associated with Less Aggressive End-of-Life Care in Patients Undergoing Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2018;24(5):1035–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doll KM, Stine JE, Van Le L, et al. Outpatient end of life discussions shorten hospital admissions in gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130(1):152–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zakhour M, LaBrant L, Rimel BJ, et al. Too much, too late: Aggressive measures and the timing of end of life care discussions in women with gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;138(2):383–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoerger M, Greer JA, Jackson VA, et al. Defining the Elements of Early Palliative Care That Are Associated With Patient-Reported Outcomes and the Delivery of End-of-Life Care. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(11):1096–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahluwalia SC, Tisnado DM, Walling AM, et al. Association of Early Patient-Physician Care Planning Discussions and End-of-Life Care Intensity in Advanced Cancer. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2015;18(10):834–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Apostol CC, Waldfogel JM, Pfoh ER, et al. Association of goals of care meetings for hospitalized cancer patients at risk for critical care with patient outcomes. Palliative medicine. 2015;29(4):386–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garrido MM, Balboni TA, Maciejewski PK, Bao Y, Prigerson HG. Quality of life and cost of care at the end of life: The role of advance directives. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2015;49(5):828–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garrido MM, Prigerson HG, Bao Y, MacIejewski PK. Chemotherapy Use in the Months before Death and Estimated Costs of Care in the Last Week of Life. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2016;51(5):875–881.e872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loggers ET, Maciejewski PK, Jimenez R, et al. Predictors of intensive end-of-life and hospice care in Latino and white advanced cancer patients. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(10):1249–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pedraza SL, Culp S, Knestrick M, Falkenstine E, Moss AH. Association of Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment Form Use With End-of-Life Care Quality Metrics in Patients With Cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(10):e881–e888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rocque GB, Dionne-Odom JN, Sylvia Huang CH, et al. Implementation and Impact of Patient Lay Navigator-Led Advance Care Planning Conversations. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2017;53(4):682–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma RK, Prigerson HG, Penedo FJ, Maciejewski PK. Male-female patient differences in the association between end-of-life discussions and receipt of intensive care near death. Cancer. 2015;121(16):2814–2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zaros MC, Curtis JR, Silveira MJ, Elmore JG. Opportunity lost: end-of-life discussions in cancer patients who die in the hospital. Journal of hospital medicine. 2013;8(6):334–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gramling R, Ingersoll LT, Anderson W, et al. End-of-Life Preferences, Length-of-Life Conversations, and Hospice Enrollment in Palliative Care: A Direct Observation Cohort Study among People with Advanced Cancer. Journal of palliative medicine. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marcia L, Ashman ZW, Pillado EB, Kim DY, Plurad DS. Advance directive and do-not-resuscitate status among advanced cancer patients with acute care surgical consultation. American Surgeon. 2018;84(10):1565–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patel MI, Sundaram V, Desai M, et al. Effect of a Lay Health Worker Intervention on Goals-of-Care Documentation and on Health Care Use, Costs, and Satisfaction Among Patients With Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA oncology. 2018;4(10):1359–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmidt TA, Zive D, Fromme EK, Cook JN, Tolle SW. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST): lessons learned from analysis of the Oregon POLST Registry. Resuscitation. 2014;85(4):480–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eckhert EE, Schoenbeck KL, Galligan D, McNey LM, Hwang J, Mannis GN. Advance care planning and end-of-life care for patients with hematologic malignancies who die after hematopoietic cell transplant. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52(6):929–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahluwalia SC, Tisnado DM, Walling AM, et al. Association of Early Patient-Physician Care Planning Discussions and End-of-Life Care Intensity in Advanced Cancer. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(10):834–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pedraza S, Knestrick M, Culp S, Falkenstine E, Moss A. Association of post form use with quality end-of-life care metrics in cancer patients: Update from the west virginia registry. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2017;53(2):367–368. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang B, Nilsson ME, Prigerson HG. Factors important to patients’ quality of life at the end of life. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(15):1133–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mack JW, Paulk ME, Viswanath K, Prigerson HG. Racial disparities in the outcomes of communication on medical care received near death. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(17):1533–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith AK, McCarthy EP, Paulk E, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in advance care planning among patients with cancer: impact of terminal illness acknowledgment, religiousness, and treatment preferences. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(25):4131–4137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.True G, Phipps EJ, Braitman LE, Harralson T, Harris D, Tester W. Treatment preferences and advance care planning at end of life: the role of ethnicity and spiritual coping in cancer patients. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30(2):174–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zafar SY, Chino F, Ubel PA, et al. The utility of cost discussions between patients with cancer and oncologists. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(9):607–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klingler C, in der Schmitten J, Marckmann G. Does facilitated Advance Care Planning reduce the costs of care near the end of life? Systematic review and ethical considerations. Palliative medicine. 2016;30(5):423–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Apostol CC, Waldfogel JM, Pfoh ER, et al. Association of goals of care meetings for hospitalized cancer patients at risk for critical care with patient outcomes. Palliative Medicine. 2015;29(4):386–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.O’Connor TL, Ngamphaiboon N, Groman A, et al. Hospice utilization and end-of-life care in metastatic breast cancer patients at a comprehensive cancer center. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2015;18(1):50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]