Abstract

Endocrine disruptors, such as phthalates, are suspected of affecting reproductive function. The Mesalamine and Reproductive Health Study (MARS) was designed to address the physiological effect of in vivo phthalate exposure on male reproduction in patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). As part of this effort, the effect on sperm RNAs to DBP exposure were longitudinally assessed using a cross-over cross-back binary design of high or background, exposures to DBP. As the DBP level was altered, numerous sperm RNA elements (REs) were differentially expressed, suggesting that exposure to or removal from high DBP produces effects that require longer than one spermatogenic cycle to resolve. In comparison, small RNAs were minimally affected by DBP exposure. While initial study medication (high or background) implicates different biological pathways, initiation on the high-DBP condition activated oxidative stress and DNA damage pathways. The negative correlation of REs with specific genomic repeats suggests a regulatory role. Using ejaculated sperm, this work provides insight into the male germline’s response to phthalate exposure.

Subject terms: Environmental impact, Risk factors

Introduction

Humans are ubiquitously exposed to, exogenous chemicals that act as endocrine disruptors. There are many different types of phthalates and their metabolites have varied capacities for modifying the endocrine system1–3. They are known to interact through peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptors (PPAR) and xenobiotic sensors1,2. Ortho-phthalates are commonly used as solvents and plasticizers in numerous consumer products, such as personal care products and polyvinyl chloride plastics4. They have also been incorporated into the coatings of some medications5–9. Although considerable literature suggests that gestational and neonatal phthalate exposure is detrimental to reproductive function of the offspring10, the health effects of phthalates on human male reproductive function is not fully understood. Epidemiological studies of adult phthalate exposures and semen parameters suggest that some phthalates are associated with abnormal sperm morphology11, sperm concentration12,13, oxidative stress14, and DNA damage15. Among couples undergoing IVF, urinary phthalate concentrations in the male partner are inversely correlated with high-quality blastocysts14, suggesting a male effect. While the intergenerational impact of phthalate exposures remain unknown, murine intergenerational models, and limited human data, suggests that paternal experiences, can have phenotypic consequences in the offspring16–22. This intergenerational effect is suspected of being mediated through epigenetic mechanisms, in part by RNAs and/or chromatin and its modifiers delivered by the spermatozoon at fertilization16,19–21,23. The impact of phthalates are beginning to be assessed14,24,25.

The Mesalamine and Reproductive Health Study (MARS) (NCT01331551) was initiated (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01331551) to directly address the in vivo effect of phthalate exposure on male reproduction. The MARS study was designed to assess semen quality5 and hormone levels6,7 in human males through a novel cross-over and cross-back study after exposure to, and removal of exposure to very high-DBP. Using a crossover design and longitudinal data structure, each subject acted as their own control, thus mitigating the genetic and environmental variation that often complicates causal assessment. Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) are often prescribed mesalamine, a medication which, in some formulations, contains di-butyl phthalate (DBP) in the coating to allow for release of the active ingredient in the distal small intestine and colon9,26. The DBP-coated medication(s), at maximal dosages, range from 300–700% of the designated EPA Reference Dose (RfD) for a 150-pound individual27–29. The use of the DBP-coated medication produces urinary monobutyl-phthalate (MBP) levels 1000x higher than the levels found in the general U.S. population5. The MARS study recruited 73 individuals, who provided up to six semen, urine, and blood samples. As described in detail5, a subset of the subjects provided longitudinal samples across alternating high and background DBP exposures, with 60 subjects enrolled in the full protocol5.

Ejaculated spermatozoa, and their RNAs provide a snapshot of transcriptomic processes, capturing the influence of the paternal environment16,19,20,30 during spermatogenesis. The current study applied RNA-seq to the MARS sperm samples, generating both a series of long RNA (>200 nucleotides) and small (<200 bp) RNA libraries to elucidate the biological processes being modified through phthalate exposure. The transcriptomic effects of both IBD and DBP exposure were assessed as a function of sperm RNA elements (REs), to provide a robust quantitative measure of effect31. Differential responses to high-DBP exposures were readily apparent in DBP-naïve men and men chronically exposed to high-DBP mesalamine. RNA levels of transcribed genomic repeats were examined to determine which genomic repeats were well-represented in human sperm and which genomic repeats were part of the response to high-DBP mesalamine.

Results

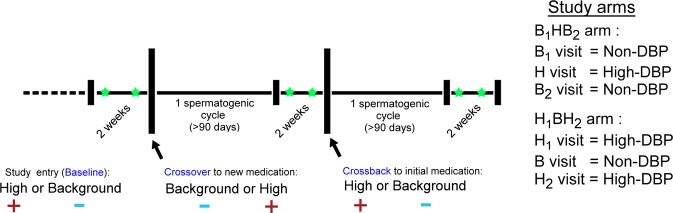

The MARS study was designed to longitudinally assess semen quality in human males as a function of high-DBP exposures. The study design is summarized in Fig. 1. Subjects entered the study having taken mesalamine, an aminosalicylate, with or without a DBP containing coating for at least 3 months5,32. Asacol® and Asacol® HD’s active ingredient is mesalamine, that uses DBP as an excipient in the enteric coating, while numerous other mesalamine formulations, such as Pentasa®, Lialda®, or Apriso®, do not use DBP5–7. Semen, blood and urine were collected at baseline, after 3 months on the alternate drug (crossover), and after a final 3 months on the arm-specific baseline drug (crossback). In order to ensure that the ejaculated spermatozoa originate from a single medication exposure, a minimum duration of 90 days (~1 spermatogenic cycle) on each medication was required prior to sample collection. This ensured that for a given sample, an entire spermatogenic cycle and subsequent ductal transport would have occurred33 on the same medication.

Figure 1.

Crossover study design. Men enter the study having taken a mesalamine medication coated with (+) or without (−) DBP for at least 3 months. Semen, blood, and urine were collected twice (green star) at baseline, after 4 months on an alternate drug (crossover), and after a final 4 months on the original drug (crossback).

In the B1HB2 arm, men entered the study on the non-DBP mesalamine i.e., background DBP exposure (B1 visit), transitioned to a high-DBP mesalamine (H visit), then returned to the non-DBP mesalamine (B2 visit). In the H1BH2 arm, subjects entered the study on high-DBP mesalamine (H1 visit), transitioned to a non-DBP mesalamine (B visit), then returned to the high-DBP mesalamine (H2 visit). Sperm and their corresponding RNAs were isolated, sequenced and quality assessed to remove failed samples (Supplementary Data). A total of 150 samples were available for analysis. In the H1BH2 arm and the B1HB2 arm, respectively, 19 and 16 subjects presented with consecutive visit pairs (e.g. baseline and crossover sets, or crossover and crossback sets) or visit trios (complete baseline, crossover, and crossback sets), with the remaining as bookended (e.g. baseline and crossback) or singletons.

Sperm REs from IBD subjects are similar to control subjects

Several studies have applied RNA-seq to IBD with a primary focus on intestinal biopsies, not distal organs. Using the MARS B1HB2 study arm as an IBD cohort, the differences between sperm samples from control males from an independent study and the B1HB2 study samples were determined. The control dataset was composed of males from idiopathic infertile couples who produced a live birth after the use of assisted reproduction technologies. The veracity of the control dataset derived from Jodar et al, is known34. Similarly, the high-quality MARS samples (Supplementary Table S1) excluded somatic cells prior to RNA extraction, and exhibited RNA profiles similar to human testis. This was confirmed through comparison of the most abundant sperm RNA elements (REs)31 to transcripts known to be highly expressed in testis (Supplementary Table S2)35. The use of REs, rather than whole genes, permitted the fine resolution and detection of differential exons and intergenic regions31. This is of particular importance in spermatozoa, which can exhibit extensive RNA fragmentation36, compounded by alternative splicing.

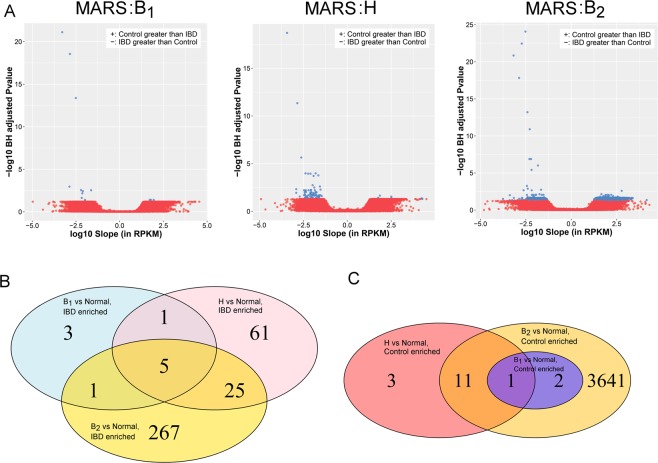

To identify sperm RNAs altered by IBD, a linear model employing random resampling (to account for visit replicates) was applied to healthy controls and each study visit (i.e, baseline, crossover and crossback) of the B1HB2 study arm, producing three sets of differential REs (IBD baseline vs control, IBD crossover vs control, and IBD crossback vs control). To ensure confidence in the differential REs, only those REs altered in two or more comparisons were considered. Relatively few REs (40 REs) were altered in at least two study visit comparisons to healthy controls (Fig. 2). Only 14 REs were upregulated in controls and 26 REs were upregulated in IBD, the majority of which were exonic REs (Supplementary Table S3). The corresponding gene names of the 40 sperm REs did not overlap with several previous studies in either human or mouse colon biopsy microarrays or RNA-seq37–45, reflecting the vastly different tissue types. This suggests that the IBD condition or chronic exposure to the drug mesalamine, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory aminosalicylate, alone does not substantially alter the transcript profile of ejaculated spermatozoa. However, among the REs upregulated in IBD compared to controls, ANKRD36 and CDHR2 that map with high resolution to two or more differential exonic REs. Within the controls, TJP1 and ARPC1A yielded two or more differential up-regulated exonic REs. This suggests that select exons are consistently up-regulated or down-regulated in sperm from DBP-naïve subjects as compared to controls. Interestingly, both CDHR2, a non-classical cadherin, and TJP1, a tight junction adaptor protein, are associated with cell-cell interactions, suggesting that IBD may modify these interactions46,47. As TJP1 is involved in linking tight junction transmembrane proteins47, the observed reduction in TJP1 levels in IBD-afflicted individuals suggests that the testis’ tight junctions may also be adversely affected.

Figure 2.

Normal and IBD differential REs. (A) Volcano plots of linear model results for all REs. Red points represent REs that are not statistically significant, while the relatively few blue points represent REs that have a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P-value less than 0.05 and an absolute slope of at least 10 RPKM. REs with a positive slope exhibit higher expression in control subjects, while those with a negative slope have higher level in IBD subjects. (B) Venn diagram of the REs enriched in the IBD subjects, across the three study visits. (C) Venn diagram of the REs enriched in the control subjects, across the three study visits.

While the only cell type assessed in this study was spermatozoa, any phthalate associated effects on spermatozoa are likely to be mediated through other supporting cell types of the male reproductive system, e.g., Sertoli or other support cells, during spermatogenesis and/or spermiogenesis. Therefore, the effects observed in spermatozoa are likely downstream of the effected cell type. In support of the above we have noted that ANKRD36, TJP1, and ARPC1A (Supplementary Table S3) are expressed (containing at least 100 reads) in cultured human Sertoli cells48. In accord with the above this suggests that the effects of IBD on spermatozoa are mediated through Sertoli cells, although the effect of IBD during epididymal transit cannot be excluded.

DBP-induced alterations in sperm RNA profiles

To assess the impact of high-DBP exposure on sperm RNAs, Linear Mixed-Effects Models (LMEM) were applied to the individual study arms, identifying the changes occurring during the baseline-crossover transition and the crossover-crossback transition. The final model adjusted for sequencing batch, subject’s time on high-DBP drug (prior to study initiation), subject’s Body Mass Index, seasonal warmth, subject’s smoking history, subject’s age, library amplification efficiency, duplication rate, and genomic alignment rate, while allowing the model’s intercept to vary across each subject. The implementation of a LMEM allowed for RNA changes across the predictive variable (i.e. study visit, indicating the use of high-DBP mediation or non-DBP mesalamine) to be assessed in each individual subject, while considering biological replicates. In each study arm and comparison, over three thousand REs were identified as differentially expressed (Supplementary Table S4), when requiring an empirical P-value less than 0.05 and minimum absolute change of 10 RPKM. As summarized in Supplementary Table S4, during the H1 to B transition in the H1BH2 arm, a total of 1150 and 293 REs respectively were upregulated and downregulated, and 832 and 779 REs, respectively, upregulated and downregulated during the B to H2 transition. In the B1HB2 arm, 1021 and 2630 REs were upregulated and downregulated, respectively, during the B1 to H transition, and 665 and 666 REs were upregulated and downregulated, respectively, during the H to B2 transition.

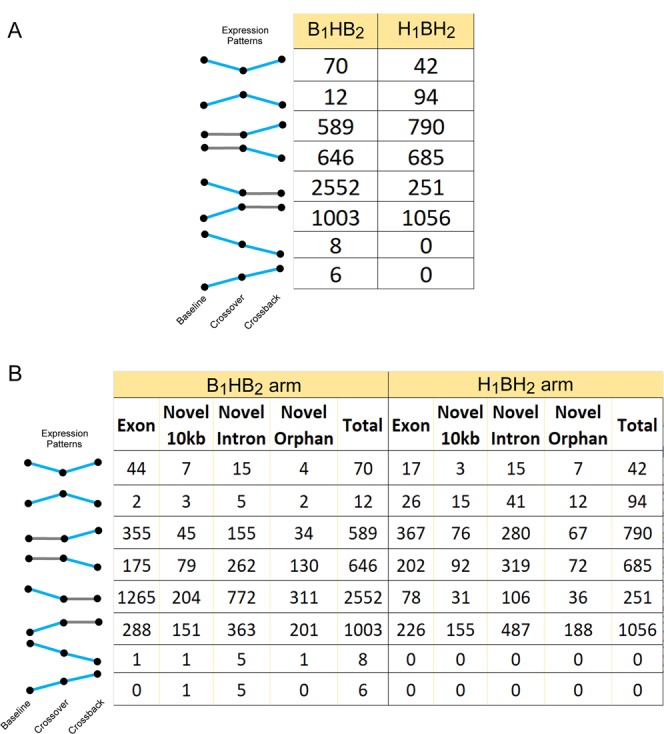

The majority of all REs were exonic (321,207 REs), with intronic REs being the most numerous of the novel classes (Near-exon: 9,730 REs; Intronic: 30,853; Orphan: 10,015). Correspondingly, the majority of REs altered by DBP were either exonic or intronic (Fig. 3). However, novel REs, highlighted by intronic REs, are major components of all observed transcript patterns, indicating that DBP exposure(s) affects far more than known transcripts. Few REs were differentially expressed in both study arms (H1BH2 arm and B1HB2 arm), suggesting that the alternating DBP exposures affects DBP-naïve males differently from males chronically exposed to high-DBP mesalamine. This arm-specific effect was also observed in sperm motility and hormonal responses of the MARS individuals5–7.

Figure 3.

Expression patterns of REs altered across MARS study arms. (A) Total RE count for a given expression pattern is shown. Expression patterns are presented to the left of the table, with blue lines indicating significant changes and grey lines indicating non-significant expression changes, measured as a function of slope.

Differential REs were then classified into specific response patterns, defining REs which either changed explicitly with high-DBP exposure. They included acute response REs that changed from baseline to crossover, followed by an opposite recovery response in REs that changed from crossover to crossback, and REs that increased or decreased across all study visits. As summarized in Fig. 3, both study arms had relatively few REs altered with DBP exposure across both transitions (1.7% and 5% in the B1HB2 arm and H1BH2 arm, respectively). Unexpectedly, the majority of differential REs in either study arm were significantly altered in a single comparison (i.e., baseline to crossover - acute response or crossover to crossback - Recovery).

Semen analysis of the MARS subjects5, showed a continuous decline in sperm motility due to a carry-over effect of high-DBP exposure in the B1HB2 arm. To examine how sperm motility RNAs may reflect this phenotype, genes known to be involved in sperm motility in mouse were overlapped with the differential exonic REs. Interestingly, several exons of sperm-motility associated genes (ATP1A4, WDR66, TEKT2, TEKT5, DRC7, CFAP44, DDX4, DNAJA1) were downregulated in the B1HB2 arm, during the initial high-DBP insult (Supplementary Table S5), consistent with the B1HB2 arm’s observed decline in sperm motility5. Several of the aforementioned downregulated genes are known sperm structural components (TEKT2, TEKT5, DRC7, CFAP44)49–52. In contrast, in the H1BH2 arm, semen parameters (including sperm motility) did not change across the study visits and few sperm-motility associated genes were linked with differential exonic REs in the H1BH2 arm. Notably, a small number of B1HB2 arm REs that were not directly associated with motility continuously increased (6 REs) or decreased (8 REs) across the study visits, while none of the H1BH2 arm REs followed a continuous pattern.

Biological response to DBP exposure

As we have shown in other systems, one would expect spermatozoal RNAs to reflect the biological processes impacted by DBP exposures53–55. Towards this end, the genes overlapping the RNAs altered by DBP exposures were assessed initially by Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment. The gene names associated with differential exonic, novel near-exon, or novel Intronic REs in the expression patterns of interest were compiled to resolve GO categories associated with both novel REs and exonic REs. Supplementary Table S6 summarizes the primary affected signaling and literature-based pathways. Few of the top GO pathways were shared between the two study arms, suggesting that shifts in DBP levels differentially affect DBP-naïve males compared to chronically exposed males. Within the B1HB2 arm, acutely downregulated REs were associated with “RAN-GAP cycling”, “Focal adhesion kinase signaling”, and “Ras GTPase binding”. RAN-GAP cycling, which is a critical component of nucleo-cytoplasmic transport, is likely involved in epigenetic regulation during spermatogenesis, via movement of regulatory RNAs56. During mammalian spermiogenesis, Ran GTPase may mediate kinesin localization, which is necessary for spermiation57,58. Interestingly, REs upregulated and downregulated in recovery phase of the B1HB2 arm were enriched for NGF signaling. NGF protein is found throughout male reproductive tissues59–62, including mammalian spermatozoa63, and outside of the suspected regulatory roles in Sertoli cells64, likely facilitates sperm motility65,66. A disruption of the NGF signaling-mediated motility in the B1HB2 arm is congruent with previously noted decreased motility5 after administration of a high-DBP mesalamine to DBP-naïve participants.

Within the H1BH2 arm, acute response REs were associated with organellar organization, which is requisite for extreme cellular and nuclear remodeling during spermatogenesis. Recovery in the H1BH2 arm suggested an involvement of “Coregulation of androgen receptor”, as well as organelle and chromatin organization. Taken together, the above GO analysis suggested that signaling pathways involved in throughout spermatogenesis, such as NGF signaling, RAN cycling, and androgen receptor signaling, may be altered due to DBP exposures. Concerted activation or repression of signaling pathways was then examined by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) to both resolve the enrichment of signaling pathways and identify the relative direction of pathway modulation (Supplementary Fig. S1).

The transition from baseline (H1 visit) to crossover (B visit), within the H1BH2 arm, did not produce any enriched pathways with notable activation or repression. However, the transition from crossover (B visit) to crossback (H2 visit), which represents the return to high-DBP mesalamine, activation of NGF signaling (Z = −1.6) was observed, consistent with the previous ontological enrichment analyses. In addition, activation of oxidative stress was indicated through mild activation of ATM signaling (Z = 0.4) and strong activation of nitric oxide production (Z = 2.3). While sumoylation and integrin-linked signaling (ILK), are repressed (Z = −1.1) and activated (Z = 1.7), respectively, both pathways have pleotrophic effects. This is consistent with previous reports of DBP-induced spermatozoal damage and oxidative stress14,15. However, the B1HB2 arm’s enriched pathways do not strongly implicate oxidative stress and a DNA damage response. The transition from baseline (B1 visit) to crossover (H visit) is associated with several spermatogenesis-related pathways, including activation of EIF2 signaling (Z = 1.9) and the PPAR-alpha/RXR-alpha signaling (Z = 2.1). These pathways were not strongly associated with either the H1BH2 arm or in the H visit vs B2 visit comparison of the B1HB2 arm, suggesting that a concerted shift in the PPAR-alpha and EIF2 pathways only occurs upon the initial high-DBP exposure. This is consistent with the current tenant that the detrimental effects of peroxisome proliferators, i.e., DBP, on germ cells likely acts through Sertoli cells1–3,67. Currently, the biological implication of repressing NF-KB signaling (Z = 1.9) and 3-phosphoinositide degradation (Z = 2.7) in the context of spermatogenesis is unknown.

In comparison, the transition from crossover (H visit) to crossback (B2 visit) revealed a different repertoire of enriched pathways, as well as a strong activation (Z = 2.1) of GP6 signaling68,69. Additionally, the retinoic acid receptor (RAR) pathway, which is a known mediator of germ cell differentiation70, was also enriched, and although no concerted activity was observed, levels of several of the altered pathway members (CARM1, SWI/SNF, NCOR1, PKC) were consistent with an activation of the retinoic acid nuclear receptor (RAR) and retinoid receptor (RXR) (via binding of retinoic acid). Notably, several of the RAR’s altered pathway members (CARM1, SWI/SNF, NCOR1) associated with changes in chromatin structure71–76 have the potential to mediate epigenetic effects of intergenerational inheritance.

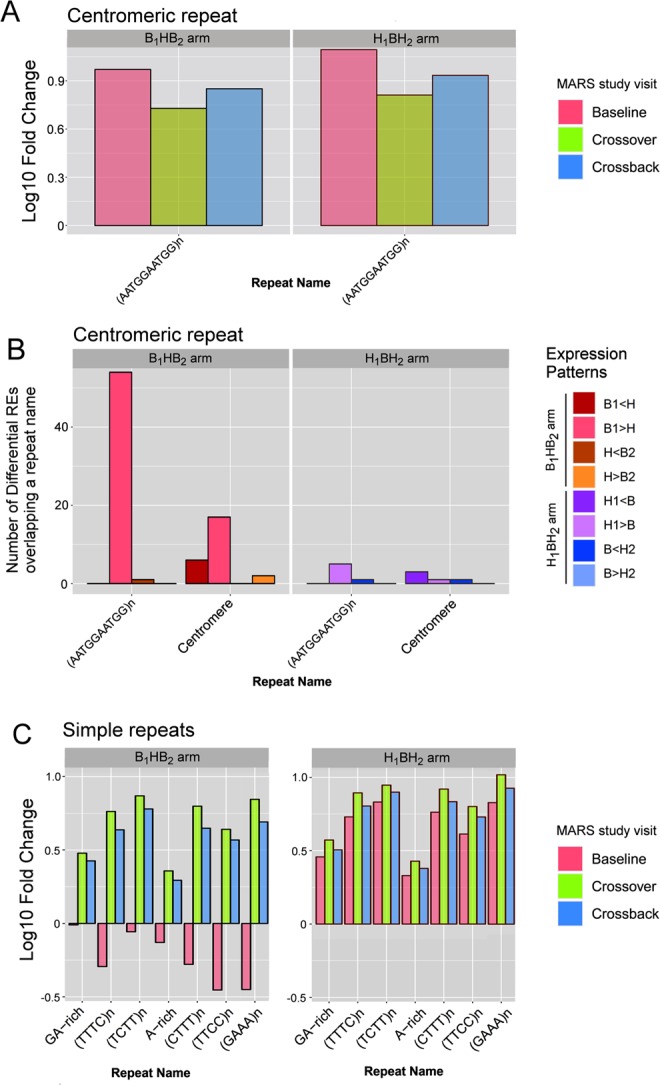

DBP exposure promotes expression of simple repeats

Several classes of repetitive element associated RNAs, including simple repeats, endogenous retroviruses, and centromeric RNAs, have been identified within the population of human spermatozoal RNAs31,77. The effect of high-DBP exposure in spermatozoa for each study arm and study visit was assessed as a function of relative enrichment/depletion of REs that overlapped a genomic repeat. Centrometric repeats and MER1A are enriched in mature human spermatozoa (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. S2) in accord with previous studies31. As expected, the centromeric repeat, (AATGGAATGG)n, is enriched across all MARS study arms (see Fig. 4A), with no distinct differences across the study arms. This centromeric enrichment is highlighted by novel orphan REs. Interestingly, the abundance of differential REs overlapping the (AATGGAATGG)n repeat decreases from the B1 visit to the H visit. As shown in Fig. 4B, this suggests that in the B1HB2 arm, the transition to high-DBP exposure reduces the levels of (AATGGAATGG)n-associated REs. Centromeric RNA has been shown to facilitate the localization of nucleoproteins and the chromosomal passenger complex (CPC)78,79. Interestingly when nuclear structures are resolved, sperm centromeres are located towards the nuclear periphery80. This is consistent with the view that centromeric repeat RNA may represent residual transcripts that, in some manner, guide sperm differentiation and/or guide mitotic progression of the early human embryo.

Figure 4.

Enrichment of repetitive element expression. (A) Repeat enrichment (positive log10 fold change) or depletion (negative log10 fold change) of centromere-associated repeats. X-axis provides the repeat name, while the Y-axis indicates the relative enrichment (positive log10 fold change) or depletion (negative log10 fold change). (B) The number of differential REs that overlap centromeric repeats. X-axis provides the repeat name, while the Y-axis indicates the number of differential REs for each significant expression change. (C) Repeat enrichment (positive log10 fold change) or depletion (negative log10 fold change) of Simple repeats. High-DBP exposure within the past spermatogenic cycle enriches simple repeats in spermatozoa.

Simple repeats, such as GA-rich repeats and variations of TC-rich repeats (e.g. (TTTC)n) were highly enriched across many of the MARS sperm samples as shown in Fig. 4C. Interestingly, simple repeats were highly enriched in all study visits and arms, with the exception of the B1 visit of the B1HB2 study arm. Within the MARS study set, the B1 visit is the sole timepoint for which sperm samples have not been exposed to high-DBP mesalamine. All novel RE classes (near-exon, intronic and orphan), but not the exonic REs, exhibit this DBP-specific pattern of repeat enrichment. Differential repeat analysis verified this DBP-specific pattern for several of the simple repeats (Supplementary Fig. S3), with the primary exceptions of GA-rich and A-rich repeat classes. These results suggest that high-DBP exposure elicits an immediate and acute response, represented by a dramatic increase in the expression of simple repeats in the male gamete. This showed that, in addition to being enriched in spermatozoa, RE-associated genomic repeats are selectively modified by DBP exposure. As these repeats are compartmentalized in sperm77, perhaps they also have a role in sperm chromatin organization. In this manner, their modification by DBP, that is known to increase DNA nicking81, may specifically alter chromatin states82.

Small RNAs altered by DBP exposure

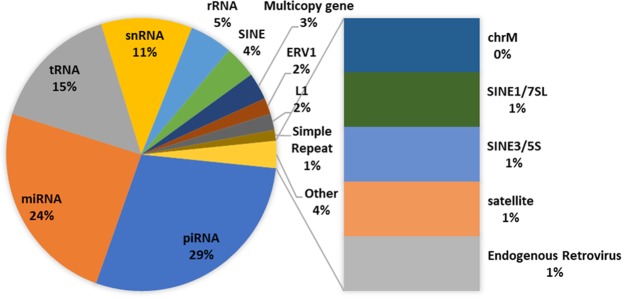

Several types of small RNAs, such as miRNAs and piRNAs, have known roles in regulating mRNA and transposable element-derived RNAs and levels of repetitive elements. Accordingly, small size-selected RNA (sncRNA)-Seq libraries, were prepared and sequenced to assess the impact of DBP exposure. Their distribution is summarized in Fig. 5. The 156 highly abundant sncRNAs exceeding a median RPM of 50 are similar to what we and others have established83–85, with piRNAs being the most abundant of the sncRNAs (Supplementary Table S7).

Figure 5.

Distribution of small RNA families in highly expressed small RNAs. Highly expressed small RNAs were defined as having a median RPM exceeding 50 across all MARS sperm samples.

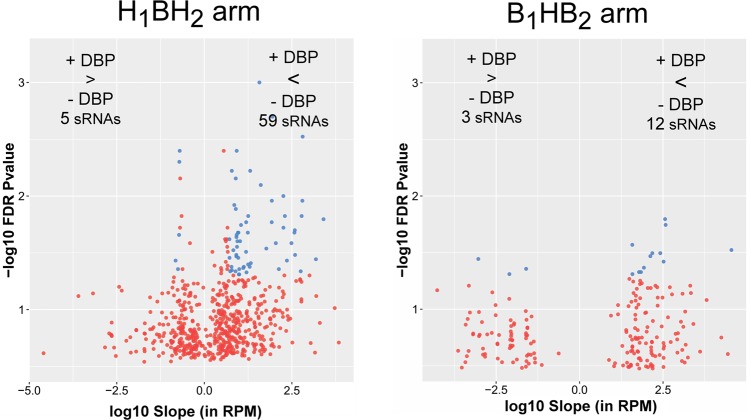

A LMEM was also applied to the individual study arms to assess the impact of DBP exposure on small spermatozoal RNAs under high-DBP and background-DBP conditions across the entire arm. This approach did not differentiate between study visits (e.g. baseline, crossover, and crossback), but instead treated samples as replicates of the associated high-DBP or background-DBP conditions. This use of this approach was necessary due to small sample sizes of the individual study visits. Both the use of an empirical P-value and Benjamini-Hochberg correction produced a similar number of significant small RNAs. For concordance with adjustment strategy employed in the long RNAs, an empirical P-value was used for the small RNAs. As shown in Fig. 6 and detailed in Supplementary Table S8, in comparison to non-DBP medication, the B1HB2 arm showed upregulation of 3 small RNAs in response to high-DBP mesalamine and downregulation of 12 small RNAs. In the H1BH2 arm, exposure to high-DBP mesalamine upregulated 9 small RNAs and downregulated 77 small RNAs. The difference in detection of differential small RNAs between study arms is likely due to the smaller sample size of the B1HB2 arm. CHARLIE3, a hAT-Charlie DNA transposon, and MER54 were differentially regulated in both study arms. Of note, CHARLIE3 was upregulated in the B1HB2 arm, yet down regulated in the H1BH2 arm upon high-DBP exposure. In contrast, MER54 was down regulated in both study arms upon high-DBP exposure. Endogenous retroviruses of the ERV3 class, of which MER54 is a member, have been previously observed in human reproductive and embryonic tissues, including placenta86,87. Currently, the phenotypic impact of a DBP-induced reduction in ERV3 RNAs during spermatogenesis and embryogenesis is not known.

Figure 6.

Volcano plots of differential small RNAs. The left and right panels show the volcano plots for the H1BH2 arm and the B1HB2 arm, respectively. The X-axis indicates the log10 expression change (slope) in RPM, while the Y-axis indicates the negative log10 empirical P-value.

Discussion

In both rural and urban environments, humans are exposed to cocktails of endocrine disruptors88. While environmental regulations designate maximum allowable levels of only a subset of the numerous xenobiotics, this level is primarily determined through animal models (including rat and mouse), which may not accurately reflect the human condition89. The human male is known to mediate some intergenerational effects in offspring19, yet the intergenerational effect of adult paternal exposures to common xenobiotics and endocrine disruptors, particularly in humans, is poorly characterized. The MARS study showed that exposure of human males to high levels of a single endocrine disruptor, di-butyl phthalate (DBP), is capable of reducing sperm motility in DBP-naïve subjects5.

Applying RNA-seq to the MARS analysis (Fig. 1) showed that DBP-induced alterations in spermatozoal RNAs were largely unique to a single study arm (either the acute B1HB2 or chronic H1BH2 study arm). Each biological response to increasing or decreasing DBP levels yielded a different altered RNA profile (Fig. 3). Interestingly, novel RE’s comprise a significant portion of altered REs, indicating that DBP exposure(s) affects far more than the previously known transcripts. The RNA profiles observed in the spermatozoa ejaculate reflect the final outcome of spermatogenesis, which includes both RNAs generated in preparation for differentiation and those acquired during epididymal maturation, also for transmission to the future embryo. Within the immunoprivileged testis (reviewed in90), the spermatogenic effect of high-DBP mesalamine is likely communicated through Sertoli cells that support the germline during differentiation, or through the epididymis during transit, when the sperm first become exposed to other fluids.

Cell lines have previously indicated that phthalate exposure may be acting on reproductive tissues through processes that include PPAR-dependent mechanisms1–3, inducing oxidative damage14,15. In the current study, several spermatogenesis-related pathways, including activation of EIF2 signaling and the PPAR-alpha/RXR-alpha signaling, were strongly associated with the transition from baseline (B1 visit) to crossover (H visit) (Supplementary Fig. S1). This suggests that a concerted shift in the Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor alpha (PPAR-alpha) and Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2 (EIF2) pathways occurs at the initial high-DBP exposure in DBP naïve males. Conversely, within the H1BH2 arm, after a temporary respite of a single spermatogenic cycle on non-DBP medication, the return to high-DBP mesalamine activated oxidative stress and DNA damage response pathways, perhaps signaling the beginning of the repair process (Supplementary Fig. S1). The ontological association of androgen receptor coregulation in the H1BH2 arm of the MARS study also suggests that responses to in vivo adult exposures elicits androgen disruption, which has previously been implicated in phthalate-induced testicular dysgenesis syndrome. Notably, subjects in the H1BH2 arm have been chronically exposed to high-DBP mesalamine, some for several years, prior to the MARS study and are assumed to have reached a phthalate-induced expression plateau in response to the high-DBP levels. The temporary (1 spermatogenic cycle) withdrawal from high-DBP mesalamine then precedes the additional and significant stress imparted onto the germline upon re-introduction of high-DBP mesalamine. The initial changes that DBP triggers are currently undefined, as ejaculated spermatozoa serve in this study as a proxy for testicular function. However, the initial prompt to change is likely an effect of DBP on Sertoli cells and/or the supporting testicular cell types, such as Leydig cells. In both study arms, the results suggested that the processes by which chronic high-DBP exposure modifies testicular function are different from those processes needed to recover from the exposure.

Among the genomic repetitive elements shown to be enriched in spermatozoa, TC-rich tetramers form a larger contribution to the sperm RNA when an individual has experienced a high-DBP exposure in the previous spermatogenic cycle (Fig. 4). The time required to fully recover is not known and may well be far longer than the single crossback cycle observed in the B1HB2 arm of the current study. Nevertheless, the study indicates that any recent high-DBP exposure increases the abundance of simple repeats in human spermatozoa. The biological function of these recurring simple repeats in spermatogenesis, fertilization and early embryo development has yet to be categorically defined31. However, they are compartmentalized in sperm77, perhaps reflective of a role in sperm chromatin organization. Phthalate’s noted ability to increase DNA nicking81 and thus spermatozoal DNA fragmentation14,15 in a specific manner82 may also alter the specialized compact chromatin environment in spermatozoa. Currently, the physiological effect(s) of the cocktail of background exposure to endocrine disruptors in humans, particularly in somatic tissue, is unknown. However, given the potential intergenerational effects of the paternal germline (mediated by sperm RNA content and sperm epigenome), ubiquitous human exposure to phthalates and other known endocrine disruptors remains a concern.

The MARS study also provided the opportunity to assess the spermatozoal impact of mild Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). IBD, defined as Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, is a common condition, with a prevalence of approximately 1 per 500 people91. The current study compared males with non-flaring, mild IBD treated daily with mesalamine to a control cohort of fertile males from idiopathic infertile couples. As expected, mild IBD, or chronic mesalamine use, had minimal impact on spermatozoal RNAs (Fig. 2).

At present, the MARS study demonstrates that exposure of human males to high levels of a single endocrine disruptor, di-butyl phthalate (DBP), is capable of altering spermatozoal RNAs and expression of genomic repeats in sperm. Furthermore, an individual’s history of high-DBP exposure influences their reproductive response to changes in DBP levels. The time period required to fully recover from a high-DBP exposure, if it is possible, has yet to be determined. However, this study suggests that recovery is at least longer than a single spermatogenic cycle (approximately 90 days). Future in vitro and in vivo experiments relevant to adult phthalate exposures are required to identify the mechanisms and pinpoint the biological processes at work in the reproductive and endocrine systems of phthalate-exposed adults. Observational studies of offspring from DBP-exposed fathers will provide a path to determine the extent of the impact that paternal DBP exposure presents as health risk to their subsequent children.

Materials and Methods

The use of human tissues was approved by the Wayne State University Human Investigation Committee and carried out under Wayne State University Human Investigation Committee IRB Protocol 095701MP2E(5R) in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations after informed consent was obtained from the collection sites. The study was approved by the institutional review boards Partners (MGH) protocol number is 2005P001631 of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, BIMC, BWH and MGH. All men signed informed consents.

Sperm purification and RNA-seq library construction

RNA isolation and RNA-seq library construction was as essentially described34,92,93. In brief, to construct long RNA-seq libraries, after RNA isolation and DNase treatment, two nanograms of RNA per sample was subject to Seqplex (Sigma-Aldrich) amplification. Fifty nanograms of Seqplex cDNA product was then subjected to NEBNext Ultra DNA Library construction (New England Biolabs) to create sequencing libraries. All samples were subject to paired-end sequencing using either the NextSeq 500 (Illumina) sequencer, HiSeq 2500 (Illumina) sequencer or the HiSeq 4000 (Illumina) sequencer.

To construct small RNA-seq libraries, one nanogram of small RNA per sample was subjected to the NEXTflex Small RNA-Seq v2 (Bioo Scientific) protocol as detailed by the manufacturer. Complete barcoded libraries were quantitated and pooled for sequencing. Samples were subject to paired-end sequencing using the MiSeq (Illumina) sequencer.

RNA-seq data processing methods

Sperm RNA-seq datasets used as the control cohort from couples who had a Live Birth were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), accession number GSE6568334. MARS long RNA libraries were processed similarly to the GSE65683 samples. Paired-end reads were trimmed of adaptors and low-quality bases prior to alignment to the consensus human ribosomal RNA (GenBank: U13369.1), the human genome (hg38) and exogenous RNA spike-in sequences, using HISAT2 (version 2.0.6). Read alignments to the human genome, exogenous RNAs, and U13369.1 were processed to remove duplicated reads using Picardtools MarkDuplicates (version 1.129). Poorly performing MARS samples were removed after examination of alignment statistics and similarity to human testicular RNA-seq from GTEx (https://www.gtexportal.org/home/) and sperm RNA veracity was assessed as described (Supplementary Materials) allowing for the quantitative classification of samples.

RNA element (RE) discovery algorithm, REDa, (described in31) was applied to the MARS and GSE65683 (control) samples. Expression (in Reads Per Kilobase per Million - RPKM) for the RE loci was then calculated for all MARS and GSE65683 samples.

Small RNA

MARS small RNA libraries were trimmed of adaptors and low-quality bases, followed by removal of reads smaller than 13 bp. sncRNAbench (version 10.14)94 was used for assigning reads to small RNA types and repeat classes, followed by a custom code for generating normalized expression values (RPM- Reads Per Million). Based on a yield of 0.3 fg of sncRNA/sperm cell, a threshold of 50,000 input reads for subsequent analysis were required of which 94% of the samples fulfilled. Common types of small RNAs of interest, such as miRNAs, piRNAs, tRNAs, tRNA fragments, and siRNA can be detected with small RNA libraries (miRNAs ~22 bp)95, piRNA ~24–31 bp96, and tRNA fragments ~28- to 34-nt20). All small and long RNA libraries are archived (GSE129216).

Differential long RNAs

The control cohort was composed of 52 subjects from idiopathic infertile couples who sought reproductive care and presented with a live birth34. The control samples are assumed to be free of inflammatory bowel disease or ulcerative colitis, and are thus considered “Normal” in differential analyses. To identify REs modified by IBD, a linear model was used to compare the Normal sperm to the B1HB2 arm of the MARS study, with three total comparisons being performed (Normal vs B1; Normal vs H; Normal vs B2), each accounting for influential covariates and subject characteristics. Benjamini-Hochberg multiple-testing correction was applied. Significance was assigned to an RE if the absolute value of the slope exceeded 10 RPKM and the Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P-value was less than 0.05. REs modified in a consistent manner (e.g. IBD-enriched or control-enriched) in any two of the three visits (B1, H, and B2) were considered for further investigation.

To identify REs modified by DBP exposure, a Linear Mixed-Effects Model (LMEM) was used to detect REs that changed with DBP exposure. Models were applied to each study arm independently, accounting for influential covariates and subject characteristics. Two comparisons were carried out for each study arm, in order to identify changes occurring from baseline visit to crossover visits, and again from crossover visit to crossback visit. Due to the large number of REs (>100,000) tested in each comparison, an empirical (bootstrapped) P-value was generated using random resampling.

REs were subsequently classified into eight unique expression patterns, with significance determined if the absolute value of the slope exceeded 10 RPKM and the empirical P-value was less than 0.05. Differential REs were then classified into specific response patterns, defining REs which either changed explicitly with DBP exposure, i.e., acute response REs that changed from baseline to crossover visits, followed by an opposite recovery response in REs that changed from crossover to crossback visits (see top two panels of Fig. 3A). Patterns of acute change were defined as those where a RE was significantly up- or down-regulated in the baseline to crossover visit comparison, but not altered from crossover to crossback visit comparison. Patterns of recovery are defined as those where a RE did not change in the baseline to crossover visit comparison, but is significantly up- or down-regulated from crossover to crossback visits. Patterns of additional interest were those that continuously increased across the study arms or continuously decreased across the study arms.

Differential small RNAs

Human small RNA sperm samples (<50 bp) used in the study are summarized in Supplementary Table S1, with 85 small RNA libraries used in modeling. A LMEM was applied to identify differential expression between DBP state (high-DBP vs non-DBP mesalamine) for the individual study arms, while accounting for influential covariates and subject characteristics. Multiple testing correction was applied using an empirical (bootstrapped) P-value, generated using random resampling. Both the use of an empirical P-value and Benjamini-Hochberg correction produced similar results of significant small RNAs. For concordance with adjustment strategy employed in the long RNAs, an empirical P-value was used. Differential small RNAs were defined as those whose absolute value of the slope exceeded 5 RPM and empirical P-value was less than 0.05.

Repeat enrichment

Repeat enrichment was measured using the following formula, where “R” indicates the REs associated with the repeat of interest, “A” indicates the REs associated with any repeat, and the required median expression threshold for a study visit is 25 RPKM. Repeat enrichment is the change in contribution of the given repeat to the repeat population, when a given expression threshold is applied to both the repeat of interest and the total repeat population.

The statistical significance of an enrichment or depletion (indicated with a positive or negative ∆ ratio, respectively) was tested using a hypergeometric test, implemented in the stats R package. This method is similar to that implemented in Estill et al.31. The repeat enrichment analysis merely indicates if a repeat type is relatively under- or over-represented in the expressed REs, relative to the expected proportion when no expression threshold is applied.

Ontological enrichment and pathway analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment was generated using the GeneRanker function of Genomatix (Eldorado version 12-2017), from the Genomatix software suite (https://www.genomatix.de/), version 3.10. The gene names associated with differential exonic, novel near-exon, or novel Intronic REs were compiled and used as input to GeneRanker. Pathway enrichment was assessed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) (version 1–13, Content build 46901286). The expression changes occurring in differential exonic REs were compiled and used as input for IPA. The expression changes of all differential exonic REs belonging to a given gene were averaged. This produced a single slope, p-value, and computed log2ratio for each gene name.

To identify DBP-altered exonic REs originating from genes involved in sperm motility, all murine genes in MGI database with the associated Gene Ontology term “sperm motility” (GO:0097722, http://www.informatics.jax.org/go/term/GO:0097722) were downloaded and transformed into the HGNC (human) gene symbol using custom R code and the BiomaRt package. The gene symbols associated with the differential exonic REs, partitioned according to expression change, were then overlapped with the list of HGNC gene symbols.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Wayne State University Grid computing facility for continuing support and resources and Genomatix for continued software support. We thank the study subjects who participated in the MARS study. We also thank research staff at Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, including Jennifer Ford and Ramace Dadd and Robert Goodrich, Department of Ob/Gyn Wayne State University for RNA isolation, characterization and sequencing. This work was supported through the Charlotte B. Failing Professorship to SAK and NIH grants ES017285, ES009718 and ES000002 to RH. Support in part to MSE from the Wayne State University’s Center for Molecular Medicine and Genetics Graduate Assistantship is appreciated.

Author Contributions

R.H., F.L.N., A.M. and S.A.K. planned the MARS study; R.H., F.L.N., and A.M. provided sperm samples for sequencing; S.A.K. directed RNA isolation, characterization and construction and sequencing of the RNA-seq libraries; M.S.E., R.H., F.L.N. and S.A.K. planned data analysis approaches and reviewed all analyzed data; M.S.E. performed data analysis; M.S.E., R.H., F.L.N., A.M. and S.A.K. wrote, edited, and approved the manuscript.

Data Availability

The RNA-seq datasets from this study have been deposited as GEO Datasets with the following accession number: GSE129216.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-48441-5.

References

- 1.Kratochvil Isabel, Hofmann Tommy, Rother Sandra, Schlichting Rita, Moretti Rocco, Scharnweber Dieter, Hintze Vera, Escher Beate I., Meiler Jens, Kalkhof Stefan, Bergen Martin. Mono(2‐ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP) and mono(2‐ethyl‐5‐oxohexyl) phthalate (MEOHP) but not di(2‐ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) bind productively to the peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor γ. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2019;33(S1):75–85. doi: 10.1002/rcm.8258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laurenzana EM, Coslo DM, Vigilar MV, Roman AM, Omiecinski CJ. Activation of the Constitutive Androstane Receptor by Monophthalates. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2016;29:1651–1661. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurst CH, Waxman DJ. Activation of PPARα and PPARγ by Environmental Phthalate Monoesters. Toxicological Sciences. 2003;74:297–308. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nassan FL, et al. Personal Care Product Use in Men and Urinary Concentrations of Select Phthalate Metabolites and Parabens: Results from the Environment And Reproductive Health (EARTH) Study. Environmental health perspectives. 2017;125:087012. doi: 10.1289/ehp1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nassan FL, et al. A crossover–crossback prospective study of dibutyl-phthalate exposure from mesalamine medications and semen quality in men with inflammatory bowel disease. Environment International. 2016;95:120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nassan FL, et al. Dibutyl-phthalate exposure from mesalamine medications and serum thyroid hormones in men. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 2019;222:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2018.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nassan FL, et al. A crossover–crossback prospective study of dibutyl-phthalate exposure from mesalamine medications and serum reproductive hormones in men. Environmental Research. 2018;160:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernández-Díaz S, Mitchell Allen A, Kelley Katherine E, Calafat Antonia M, Hauser R. Medications as a Potential Source of Exposure to Phthalates in the U.S. Population. Environmental health perspectives. 2009;117:185–189. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hauser R, Duty S, Godfrey-Bailey L, Calafat Antonia M. Medications as a source of human exposure to phthalates. Environmental health perspectives. 2004;112:751–753. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veeramachaneni DNR, Gary RK. Phthalate-induced pathology in the foetal testis involves more than decreased testosterone production. Reproduction. 2014;147:435–442. doi: 10.1530/REP-13-0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang C, et al. The classic EDCs, phthalate esters and organochlorines, in relation to abnormal sperm quality: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:19982. doi: 10.1038/srep19982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duty SM, et al. Phthalate Exposure and Human Semen Parameters. Epidemiology. 2003;14:269–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hallas J, et al. Association between use of phthalate-containing medication and semen quality among men in couples referred for assisted reproduction. Human Reproduction. 2018;33:503–511. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu H, et al. Preconception urinary phthalate concentrations and sperm DNA methylation profiles among men undergoing IVF treatment: a cross-sectional study. Human Reproduction. 2017;32:2159–2169. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauser R, et al. DNA damage in human sperm is related to urinary levels of phthalate monoester and oxidative metabolites. Human Reproduction. 2007;22:688–695. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodgers AB, Morgan CP, Leu NA, Bale TL. Transgenerational epigenetic programming via sperm microRNA recapitulates effects of paternal stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112:13699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508347112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodgers AB, Morgan CP, Bronson SL, Revello S, Bale TL. Paternal Stress Exposure Alters Sperm MicroRNA Content and Reprograms Offspring HPA Stress Axis Regulation. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33:9003. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0914-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan CP, Bale TL. Early Prenatal Stress Epigenetically Programs Dysmasculinization in Second-Generation Offspring via the Paternal Lineage. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:11748. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1887-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vågerö D, Pinger PR, Aronsson V, van den Berg GJ. Paternal grandfather’s access to food predicts all-cause and cancer mortality in grandsons. Nature Communications. 2018;9:5124. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07617-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma U, et al. Biogenesis and function of tRNA fragments during sperm maturation and fertilization in mammals. Science. 2016;351:391. doi: 10.1126/science.aad6780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Q, et al. Sperm tsRNAs contribute to intergenerational inheritance of an acquired metabolic disorder. Science. 2016;351:397. doi: 10.1126/science.aad7977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stanford KI, et al. Paternal Exercise Improves Glucose Metabolism in Adult Offspring. Diabetes. 2018;67:2530. doi: 10.2337/db18-0667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swanson, G. et al. Human Chromatin remodeler cofactor, RNA interactor, Eraser and Writer Sperm RNAs responding to Obesity. Epigenetics. PMID: 31354029 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Wu H, et al. Parental contributions to early embryo development: influences of urinary phthalate and phthalate alternatives among couples undergoing IVF treatment. Human Reproduction. 2016;32:65–75. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wirth JJ, et al. A Pilot Study Associating Urinary Concentrations of Phthalate Metabolites and Semen Quality. Systems Biology in Reproductive Medicine. 2008;54:143–154. doi: 10.1080/19396360802055921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hait Elizabeth J, Calafat Antonia M, Hauser Russ. Urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations among men with inflammatory bowel disease on mesalamine therapy. Endocrine Disruptors. 2013;1(1):e25066. doi: 10.4161/endo.25066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dibutyl phthalate; CASRN 84-74-2 (1987).

- 28.GmbH, W. C. D. Prescribing information for ASACOL (mesalamine) delayed-release tablets, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/019651s025lbl.pdf (2015).

- 29.Allergan, I. ASACOL HD- mesalamine tablet, delayed release, https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/ (2013).

- 30.Dias Brian G, Ressler Kerry J. Parental olfactory experience influences behavior and neural structure in subsequent generations. Nature Neuroscience. 2013;17(1):89–96. doi: 10.1038/nn.3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Estill Molly S, Hauser Russ, Krawetz Stephen A. RNA element discovery from germ cell to blastocyst. Nucleic Acids Research. 2018;47(5):2263–2275. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harinstein, L., Greene, P., Wu, E. & Ready, T. Asacol and Asacol HD Safety and Drug Utilization Review. (Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 2016).

- 33.Amann RP. The Cycle of the Seminiferous Epithelium in Humans: A Need to Revisit? Journal of Andrology. 2008;29:469–487. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.107.004655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jodar M, et al. Absence of sperm RNA elements correlates with idiopathic male infertility. Science Translational Medicine. 2015;7:295re296. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lonsdale John, Thomas Jeffrey, Salvatore Mike, Phillips Rebecca, Lo Edmund, Shad Saboor, Hasz Richard, Walters Gary, Garcia Fernando, Young Nancy, Foster Barbara, Moser Mike, Karasik Ellen, Gillard Bryan, Ramsey Kimberley, Sullivan Susan, Bridge Jason, Magazine Harold, Syron John, Fleming Johnelle, Siminoff Laura, Traino Heather, Mosavel Maghboeba, Barker Laura, Jewell Scott, Rohrer Dan, Maxim Dan, Filkins Dana, Harbach Philip, Cortadillo Eddie, Berghuis Bree, Turner Lisa, Hudson Eric, Feenstra Kristin, Sobin Leslie, Robb James, Branton Phillip, Korzeniewski Greg, Shive Charles, Tabor David, Qi Liqun, Groch Kevin, Nampally Sreenath, Buia Steve, Zimmerman Angela, Smith Anna, Burges Robin, Robinson Karna, Valentino Kim, Bradbury Deborah, Cosentino Mark, Diaz-Mayoral Norma, Kennedy Mary, Engel Theresa, Williams Penelope, Erickson Kenyon, Ardlie Kristin, Winckler Wendy, Getz Gad, DeLuca David, MacArthur Daniel, Kellis Manolis, Thomson Alexander, Young Taylor, Gelfand Ellen, Donovan Molly, Meng Yan, Grant George, Mash Deborah, Marcus Yvonne, Basile Margaret, Liu Jun, Zhu Jun, Tu Zhidong, Cox Nancy J, Nicolae Dan L, Gamazon Eric R, Im Hae Kyung, Konkashbaev Anuar, Pritchard Jonathan, Stevens Matthew, Flutre Timothèe, Wen Xiaoquan, Dermitzakis Emmanouil T, Lappalainen Tuuli, Guigo Roderic, Monlong Jean, Sammeth Michael, Koller Daphne, Battle Alexis, Mostafavi Sara, McCarthy Mark, Rivas Manual, Maller Julian, Rusyn Ivan, Nobel Andrew, Wright Fred, Shabalin Andrey, Feolo Mike, Sharopova Nataliya, Sturcke Anne, Paschal Justin, Anderson James M, Wilder Elizabeth L, Derr Leslie K, Green Eric D, Struewing Jeffery P, Temple Gary, Volpi Simona, Boyer Joy T, Thomson Elizabeth J, Guyer Mark S, Ng Cathy, Abdallah Assya, Colantuoni Deborah, Insel Thomas R, Koester Susan E, Little A Roger, Bender Patrick K, Lehner Thomas, Yao Yin, Compton Carolyn C, Vaught Jimmie B, Sawyer Sherilyn, Lockhart Nicole C, Demchok Joanne, Moore Helen F. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nature Genetics. 2013;45(6):580–585. doi: 10.1038/ng.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sendler E, et al. Stability, delivery and functions of human sperm RNAs at fertilization. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013;41:4104–4117. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holgersen K, et al. High-Resolution Gene Expression Profiling Using RNA Sequencing in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease and in Mouse Models of Colitis. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2015;9:492–506. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mirza AH, et al. Transcriptomic landscape of lncRNAs in inflammatory bowel disease. Genome Medicine. 2015;7:39. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0162-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gillberg L, et al. Nitric oxide pathway-related gene alterations in inflammatory bowel disease. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;47:1283–1298. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.706830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cooke J. Mucosal genome-wide methylation changes in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2012;18:2128–2137. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Camilleri M, et al. RNA sequencing shows transcriptomic changes in rectosigmoid mucosa in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea: a pilot case-control study. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2014;306:G1089–G1098. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00068.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hong SN, et al. RNA-seq Reveals Transcriptomic Differences in Inflamed and Noninflamed Intestinal Mucosa of Crohn’s Disease Patients Compared with Normal Mucosa of Healthy Controls. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2017;23:1098–1108. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taman H, et al. Transcriptomic Landscape of Treatment—Naïve Ulcerative Colitis. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2018;12:327–336. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peters Lauren A, Perrigoue Jacqueline, Mortha Arthur, Iuga Alina, Song Won-min, Neiman Eric M, Llewellyn Sean R, Di Narzo Antonio, Kidd Brian A, Telesco Shannon E, Zhao Yongzhong, Stojmirovic Aleksandar, Sendecki Jocelyn, Shameer Khader, Miotto Riccardo, Losic Bojan, Shah Hardik, Lee Eunjee, Wang Minghui, Faith Jeremiah J, Kasarskis Andrew, Brodmerkel Carrie, Curran Mark, Das Anuk, Friedman Joshua R, Fukui Yoshinori, Humphrey Mary Beth, Iritani Brian M, Sibinga Nicholas, Tarrant Teresa K, Argmann Carmen, Hao Ke, Roussos Panos, Zhu Jun, Zhang Bin, Dobrin Radu, Mayer Lloyd F, Schadt Eric E. A functional genomics predictive network model identifies regulators of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature Genetics. 2017;49(10):1437–1449. doi: 10.1038/ng.3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mo A, et al. Disease-specific regulation of gene expression in a comparative analysis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease. Genome Medicine. 2018;10:48. doi: 10.1186/s13073-018-0558-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.GeneCards. Cadherin Related Family Member 2, https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=CDHR2 (2019).

- 47.GeneCards. Tight Junction Protein 1, https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=TJP1 (2019).

- 48.Ribeiro MA, et al. Integrative transcriptome and microRNome analysis identifies dysregulated pathways in human Sertoli cells exposed to TCDD. Toxicology. 2018;409:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.GeneCards. Tektin 2, https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=TEKT2 (2019).

- 50.GeneCards. Tektin 5, https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=TEKT5 (2019).

- 51.GeneCards. Dynein Regulatory Complex Subunit 7, https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=DRC7 (2019).

- 52.GeneCards. Cilia And Flagella Associated Protein 44, https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=CFAP44 (2019).

- 53.Ostermeier GC, Goodrich RJ, Diamond MP, Dix DJ, Krawetz SA. Toward using stable spermatozoal RNAs for prognostic assessment of male factor fertility. Fertility and Sterility. 2005;83:1687–1694. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ostermeier GC, Dix DJ, Miller D, Khatri P, Krawetz SA. Spermatozoal RNA profiles of normal fertile men. The Lancet. 2002;360:772–777. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09899-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Platts AE, et al. Success and failure in human spermatogenesis as revealed by teratozoospermic RNAs. Human Molecular Genetics. 2007;16:763–773. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dattilo, V. et al. SGK1 affects RAN/RANBP1/RANGAP1 via SP1 to play a critical role in pre-miRNA nuclear export: a new route of epigenomic regulation. Scientific Reports 7, 45361, 10.1038/srep45361, https://www.nature.com/articles/srep45361#supplementary-information (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Wang D-H, Ma D-D, Yang W-X. Kinesins in spermatogenesis†. Biology of Reproduction. 2017;96:267–276. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.116.144113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zou Y, Sperry AO, Millette CF. KRP3A and KRP3B: Candidate Motors in Spermatid Maturation in the Seminiferous Epithelium1. Biology of Reproduction. 2002;66:843–855. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.3.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ayer-LeLievre C, Olson L, Ebendal T, Hallböök F, Persson H. Nerve growth factor mRNA and protein in the testis and epididymis of mouse and rat. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1988;85:2628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seidl K, Holstein AF. Evidence for the presence of nerve growth factor (NGF) and NGF receptors in human testis. Cell and Tissue Research. 1990;261:549–554. doi: 10.1007/BF00313534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uhlén M, et al. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347:1260419. doi: 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jin W, et al. Cellular localization of NGF and its receptors trkA and p75LNGFR in male reproductive organs of the Japanese monkey, Macaca fuscata fuscata. Endocrine. 2006;29:155–160. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:29:1:155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li C, et al. Detection of nerve growth factor (NGF) and its specific receptor (TrkA) in ejaculated bovine sperm, and the effects of NGF on sperm function. Theriogenology. 2010;74:1615–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2010.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Perrard M-H, Chassaing E, Montillet G, Sabido O, Durand P. Cytostatic Factor Proteins Are Present in Male Meiotic Cells and β-Nerve Growth Factor Increases Mos Levels in Rat Late Spermatocytes. Plos One. 2009;4:e7237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jin W, Tanaka A, Watanabe G, Matsuda H, Taya K. Effect of NGF on the Motility and Acrosome Reaction of Golden Hamster Spermatozoa In Vitro. Journal of Reproduction and Development. 2010;56:437–443. doi: 10.1262/jrd.09-219N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin K, et al. Nerve growth factor promotes human sperm motility in vitro by increasing the movement distance and the number of A grade spermatozoa. Andrologia. 2015;47:1041–1046. doi: 10.1111/and.12375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang X, et al. Inhibition of PPARα attenuates vimentin phosphorylation on Ser-83 and collapse of vimentin filaments during exposure of rat Sertoli cells in vitro to DBP. Reproductive Toxicology. 2014;50:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koehler JK, Nudelman ED, Hakomori S. A collagen-binding protein on the surface of ejaculated rabbit spermatozoa. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1980;86:529. doi: 10.1083/jcb.86.2.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li S, Garcia M, Gewiss RL, Winuthayanon W. Crucial role of estrogen for the mammalian female in regulating semen coagulation and liquefaction in vivo. PLOS Genetics. 2017;13:e1006743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Busada, J. T. & Geyer, C. B. The Role of Retinoic Acid (RA) in Spermatogonial Differentiation1. Biology of Reproduction94, 10, 11-10-10, 11-10, 10.1095/biolreprod.115.135145 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Morales Y, Cáceres T, May K, Hevel JM. Biochemistry and regulation of the protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2016;590:138–152. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alver, B. H. et al. The SWI/SNF chromatin remodelling complex is required for maintenance of lineage specific enhancers. Nature Communications8, 14648, 10.1038/ncomms14648, https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms14648#supplementary-information (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Meier K, Brehm A. Chromatin regulation: How complex does it get? Epigenetics. 2014;9:1485–1495. doi: 10.4161/15592294.2014.971580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Castillo J, Jodar M, Oliva R. The contribution of human sperm proteins to the development and epigenome of the preimplantation embryo. Human Reproduction Update. 2018;24:535–555. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmy017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hupalowska A, et al. CARM1 and Paraspeckles Regulate Pre-implantation Mouse Embryo Development. Cell. 2018;175:1902–1916.e1913. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jodar, M., Selvaraju, S., Sendler, E., Diamond, M. P. and Krawetz, S. A. for the Reproductive Medicine Network. The presence, roles and clinical use of spermatozoal RNAs Human Reproduction Update 19, 604–624, PMID: 23856356 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Johnson GD, Mackie P, Jodar M, Moskovtsev S, Krawetz SA. Chromatin and extracellular vesicle associated sperm RNAs. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43:6847–6859. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wong LH, et al. Centromere RNA is a key component for the assembly of nucleoproteins at the nucleolus and centromere. Genome research. 2007;17:1146–1160. doi: 10.1101/gr.6022807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Blower MD. Centromeric Transcription Regulates Aurora-B Localization and Activation. Cell Reports. 2016;15:1624–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yaron Y, et al. Centromere sequences localize to the nuclear halo of human spermatozoa. International Journal of Andrology. 1998;21:13–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.1998.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang H, Zhang J, Gao X, Zhao W, Zheng Y. Di-n-Butyl Phthalate (DBP) Exposure Induces Oxidative Damage in Testes of Adult Rats AU - Zhou, Dangxia. Systems Biology in Reproductive Medicine. 2010;56:413–419. doi: 10.3109/19396368.2010.509902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kocer A, et al. Oxidative DNA damage in mouse sperm chromosomes: Size matters. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2015;89:993–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.10.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Donkin I, et al. Obesity and Bariatric Surgery Drive Epigenetic Variation of Spermatozoa in Humans. Cell Metabolism. 2016;23:369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Krawetz SA, et al. A survey of small RNAs in human sperm. Human Reproduction. 2011;26:3401–3412. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pantano L, et al. The small RNA content of human sperm reveals pseudogene-derived piRNAs complementary to protein-coding genes. RNA. 2015;21:1085–1095. doi: 10.1261/rna.046482.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Larsson E, Andersson AC, Nilsson BO. Expression of an endogenous retrovirus (ERV3 HERV-R) in human reproductive and embryonic tissues–evidence for a function for envelope gene products. Upsala journal of medical sciences. 1994;99:113–120. doi: 10.3109/03009739409179354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Andersson A-C, et al. Developmental Expression of HERV-R (ERV3) and HERV-K in Human Tissue. Virology. 2002;297:220–225. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen Lin, Luo Kai, Etzel Ruth, Zhang Xiaoyu, Tian Ying, Zhang Jun. Co-exposure to environmental endocrine disruptors in the US population. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2019;26(8):7665–7676. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-04105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Administration, F. A. D. (ed. Food and Drug Administration) (2012).

- 90.Kaur G, Thompson LA, Dufour JM. Sertoli cells – Immunological sentinels of spermatogenesis. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2014;30:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kappelman MD, et al. The Prevalence and Geographic Distribution of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis in the United States. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2007;5:1424–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Goodrich, R., Anton, E. & Krawetz, S. A. In Methods in Molecular Biology Vol. 927 385–396 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 93.Goodrich RJ, Ostermeier GC, Krawetz SA. Multitasking with molecular dynamics Typhoon: quantifying nucleic acids and autoradiographs. Biotechnology letters. 2003;25:1061–1065. doi: 10.1023/A:1024154817579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rueda A, et al. sRNAtoolbox: an integrated collection of small RNA research tools. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43:W467–W473. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ha M, Kim VN. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2014;15:509. doi: 10.1038/nrm3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Iwasaki YW, Siomi MC, Siomi H. PIWI-Interacting RNA: Its Biogenesis and Functions. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2015;84:405–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-seq datasets from this study have been deposited as GEO Datasets with the following accession number: GSE129216.