Abstract

Background

The 2014 Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act (i.e., “Choice”) allows eligible Veterans to receive covered health care outside the Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System. The initial implementation of Choice was challenging, and use was limited in the first year.

Objective

To assess satisfaction with Choice, and identify reasons for satisfaction and dissatisfaction during its early implementation.

Design and Participants

Semi-structured telephone interviews from July to September 2015 with Choice-eligible Veterans from 25 VA facilities across the USA.

Main Measures

Satisfaction was assessed with 5-point Likert scales and open-ended questions. We compared ratings of satisfaction with Choice and VA health care, and identified reasons for satisfaction/dissatisfaction with Choice in a thematic analysis of open-ended qualitative data.

Results

Of 195 participants, 35 had not attempted to use Choice; 43 attempted but had not received Choice care (i.e., attempted only); and 117 attempted and received Choice care. Among those who attempted only, a smaller percentage were somewhat/very satisfied with Choice than with VA health care (17.9% and 71.8%, p < 0.001); among participants who received Choice, similar percentages were somewhat/very satisfied with Choice and VA health care (66.6% and 71.1%, p = 0.45). When asked what contributed to Choice ratings, participants who attempted but did not receive Choice care reported poor access (50%), scheduling problems (20%), and care coordination issues (10%); participants who received Choice care reported improved access (27%), good quality of care (19%), and good distance to Choice provider (16%). Regardless of receipt of Choice care, most participants expressed interest in using Choice in the future (70–82%).

Conclusions

Access and scheduling barriers contributed to dissatisfaction for Veterans unsuccessfully attempting to use Choice during its initial implementation, whereas improved access and good care contributed to satisfaction for those receiving Choice care. With Veterans’ continued interest in using services outside VA facilities, subsequent policy changes should address Veterans’ barriers to care.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-019-05116-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: patient satisfaction, Veterans, Veterans Choice Program, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

Beginning in 2014, news coverage of several Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) sites highlighted significant delays experienced by Veterans in accessing VA health care.1 Congress responded with the passage that year of the Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act, which allowed eligible veterans to seek private sector health care via the Veterans Choice Program (“Choice”). The urgency of reducing care wait times led the VA to rely on third-party administrators to rapidly implement Choice. While research has highlighted difficulties associated with the rapid rollout of this complex program,2, 3 the experiences of Veterans seeking care through Choice during this formative period have not been well studied.

Choice was intended to improve access by enabling Veterans to receive covered health care from providers outside of the VA if they experienced wait times for care greater than 30 days, resided more than 40 miles from the nearest VA medical facility, or experienced excessive travel burdens. To implement Choice within 90 days of the law’s passage, the VA contracted third-party administrators to establish non-VA provider networks. During the initial rollout, these administrators managed Veteran enrollment, authorized care, scheduled appointments, and billed VA for care received through Choice. Preliminary evaluations of Choice showed that only 2–13% of eligible Veterans received health care through Choice in its first year of implementation.3, 4 Those Veterans who did use Choice still reported barriers related to pre-authorization and scheduling, inadequate provider networks, and liability for treatment costs.3, 5

Veteran experiences with Choice and VA health care during the initial rollout of this new program are largely unknown. Studies of VA health care satisfaction have documented suboptimal experiences with access prior to Choice implementation. Ongoing initiatives to evaluate Veteran experiences with Choice focus on patients who successfully received services through Choice and do not include Veterans who have attempted but were unsuccessful in obtaining health care through this program. Veterans who tried unsuccessfully to use Choice during the early rollout are likely to have greater frustration and disappointment with the program, and potentially with VA health care overall.6 Understanding the perspectives of eligible Veterans who do not use Choice, as well as the experiences of those who attempted to obtain care without success, could offer a more complete picture of satisfaction/dissatisfaction with VA health care options in the era of Choice. As McGinnis noted in response to our pre-Choice work,7 extending VA satisfaction research to focus on Choice is important for determining the effectiveness of this new program.

The goal of this mixed methods study is to assess Veteran experiences with VA health care and Choice during the initial rollout in 2015. Specifically, we examine the health care experiences of Veterans attempting or not attempting to use Choice, compare satisfaction with experiences of care through Choice versus traditional VA health care, and identify reasons for satisfaction/dissatisfaction with Choice among Veterans who had attempted to receive care through this program. Research focused on the initial rollout can provide insights into patient experiences with a changing health care system, and inform the implementation of initiatives to improve Veteran access to health care outside VA facilities.

METHODS

We conducted semi-structured telephone interviews with Choice-eligible Veterans from July to October 2015. We used a concurrent mixed methods design, where Veterans were asked closed Likert scale items and open-ended qualitative questions.8 Because we were interested in a broad range of patient experiences with this new program, we conducted interviews with Veterans who had received Choice care, those who had not attempted to receive Choice care, or those who attempted but had not received Choice care. The VA Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved this study as a quality improvement project.

Participant Sampling and Recruitment

Using VA administrative records, we identified a sampling frame of Veterans eligible for Choice from 25 VA medical centers that provided care to relatively large numbers of racial/ethnic minority patients. These sites were participating in a concurrent study of racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in satisfaction with VA health care.9 Across the 25 medical centers, 44,908 outpatients were eligible for Choice based on either distance (n = 37,870, 84%), wait times (n = 1281, 3%), or both distance and wait times (n = 5757, 13%). We identified Choice users from claims records provided by third-party Choice administrators (i.e., TriWest or Health Net). Our sampling frame included all 1480 Veterans with a Choice claim and a stratified, random sample of 1002 Veterans lacking a claim by June 30, 2015. The stratified sampling was based on Choice eligibility criteria (distance or wait time), with approximately 20 Veterans selected per site. Due to small numbers sampled per site, individuals in the sampling matrix who were eligible due to wait times only were grouped with those eligible due to wait time and distance.

In waves of recruitment over time, we mailed Veterans from the sampling frame a brief study description, an invitation to participate, and an option to opt-out of study screening. We called Veterans who did not opt-out to confirm study eligibility and mailed informed consent documents to those interested in participating. Potential participants who provided written consent were called by a professional survey research organization that was contracted to conduct audio-recorded telephone interviews. Recruitment continued until the number of completed interviews reached the target of 180 to 200. While thematic saturation can typically be reached using 25 interviews in a homogenous sample,10 we had no information on the homogeneity of potential participants and conservatively chose a target of 45–50 Veterans per cell (choice use [yes or no] by reason for eligibility [distance or wait time]) to ensure thematic saturation. Survey respondents received $35 for participating.

Measures

Verification of Choice Use

We assessed whether Veterans had used Choice with two questions: (1) Have you tried to receive non-VA care under the Choice Program? and (2) Have you seen a non-VA provider using the Choice Act? Because we could not assess attempt status from administrative data, we classified participants post hoc into three mutually exclusive categories: no attempt, attempted but had not received Choice care (i.e., “attempt only”), or attempted and received Choice care.

Satisfaction

We assessed satisfaction with VA health care and Choice with 5-point Likert scales: (1) How satisfied are you with your VA health care overall? and (2) How satisfied are you with your experience of care through the Choice Program? (very dissatisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, somewhat satisfied, and very satisfied). Participants who never attempted to use Choice were not asked about their experiences with the program. In addition to satisfaction ratings, our interview included open-ended questions informed by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) on reasons for satisfaction/dissatisfaction with Choice; enrollment and administrative barriers; perceptions of access, coordination, and quality of care under Choice; and intentions to use Choice in the future (Appendix 1 in the ESM).11

Patient Characteristics

We collected self-reported demographic characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and employment status), health literacy, comorbidity, perceived health status, and reason(s) for Choice eligibility. We assessed health literacy using the question “How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself?”12 We quantified comorbidity using the individual conditions in the Charlson Comorbidity Index,13 modified to include behavioral health conditions prevalent among Veterans (i.e., depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety).9 We assessed health status using the single-item global health and 1-year prior health questions from the SF-36.14, 15 We asked participants their reason for Choice eligibility: distance > 40 miles, wait time > 30 days, or both. We extracted military service era from VA administrative records.

Methods of Analysis

Analyses proceeded in three steps. First, we compared respondent characteristics and level of satisfaction with VA care and Choice. We compared categorical variables using chi-square statistics and continuous variables using analysis of variance. Due to sparse data, we collapsed the lowest 3 Likert categories (i.e., very dissatisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied) into a single “less than satisfied” category.

Second, we compared Likert ratings of satisfaction with Choice to satisfaction with VA health care. We cross-tabulated satisfaction responses separately by receipt of care status (i.e., attempt only versus attempt and receipt). We assessed symmetry and marginal homogeneity of the Likert responses for both sources of care, as implemented in Stata version 14.16, 17

Third, we conducted a thematic analysis of audio files from the recorded interviews.18 Codes and illustrative quotes were entered into a proprietary database, powered by Microsoft SQL Server, which allowed the study to manage the number of quotes per domain more effectively than did commercial software. The study’s Principal Investigator (PI) [SZ] and the coding team developed the codebook together by listening to audio files until all relevant sources of satisfaction and dissatisfaction were captured by qualitative codes. Working in teams of two, coders applied the codebook to their assigned interviews. Larger coding meetings with the PI continued throughout the coding process to ensure coding stability and reliability. Coders also met regularly to discuss discrepancies in coding and to refine coding inclusion/exclusion criteria before producing a final master qualitative dataset. An inter-coder reliability adjudication process was applied to 20% of the interviews and adjudicated codes were added into the final qualitative dataset.

Our thematic analysis focused on expressed satisfaction and/or dissatisfaction regarding Choice among participants who attempted only or attempted and received care under Choice. We present the frequencies of satisfaction/dissatisfaction themes that emerged in the interviews, and provide illustrative quotes from both groups. In addition to the overall thematic analysis, we summarize the most common responses to specific questions: 1) What are your major reasons for not using the Choice program? 2) Will you seek care outside of the VA through the Choice Program in the future? and 3) How has your experience with the Choice Program affected your ability overall to get the care you need?

RESULTS

Recruitment

Of the 752 potentially eligible Veterans mailed an invitation to participate, 176 could not be reached by telephone, and 212 were reached and refused participation (Appendix 2 in the ESM). Among the remaining 364 participants screened, 253 were deemed eligible for the full interviews. Of those eligible, 195 completed interviews, 26 did not complete interviews within the study window, 13 declined an interview, and 18 were excluded for other reasons. Participants (n = 195) were more likely than non-participants (n = 557) to have received Choice care (73% versus 46%, p < 0.001) and less likely to be eligible for Choice services based on wait times only (9% versus 15%, p = 0.04). No differences were identified between participants and non-participants on sociodemographic variables extracted from medical records (e.g., age, sex, service connected disability; p > 0.05 for each). The final sample included 35 (18%) participants who did not attempt to use Choice, 43 (22%) who attempted only, and 117 (60%) who attempted and received Choice care.

Respondent Characteristics

Overall, most participants were non-Hispanic White, male, and married or living as married; received at least some post-high school education; and served prior to the Persian Gulf War (Table 1). The average age was 63 years, and many participants reported poor health and chronic health conditions. A majority reported comfort filling out medical forms, indicating adequate health literacy. Sixty percent of participants were eligible for Choice based on distance only, 35% were eligible based on both distance and wait time, and only 5% were eligible based on wait time only.

Table 1.

Veteran Characteristics of Respondents Eligible for the Veterans Choice Program, Stratified by Attempt and Receipt of Care in the Choice Program in 2015

| Characteristics | Attempt and receipt of care under the Veterans Choice Program | p value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No attempt (n = 35) | Attempted only* (n = 43) | Received Choice care (n = 117) | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.82 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 26 | 74.3 | 31 | 72.1 | 87 | 74.4 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 6 | 17.1 | 5 | 11.6 | 14 | 12.0 | |

| Other | 3 | 8.6 | 7 | 16.3 | 16 | 13.7 | |

| Female gender | 2 | 5.7 | 4 | 9.3 | 13 | 11.1 | 0.64 |

| Age (mean, SD) | 60.3 | 14.0 | 62.1 | 10.7 | 63.9 | 11.4 | 0.26 |

| Married/living as married | 22 | 62.9 | 21 | 48.8 | 71 | 61.2 | 0.32 |

| Education level | 0.47 | ||||||

| ≤High school/GED | 8 | 22.9 | 11 | 25.6 | 29 | 25.2 | |

| Trade school/some college | 15 | 42.9 | 25 | 58.1 | 57 | 49.6 | |

| ≥College graduate | 12 | 34.3 | 7 | 16.3 | 29 | 25.2 | |

| Employment status | 0.91 | ||||||

| Employed | 8 | 22.9 | 9 | 20.9 | 20 | 17.1 | |

| Not employed | 12 | 34.3 | 15 | 34.9 | 39 | 33.3 | |

| Retired | 15 | 42.9 | 19 | 44.2 | 58 | 49.6 | |

| Most recent service | 0.48 | ||||||

| Vietnam War | 15 | 42.9 | 26 | 60.5 | 70 | 59.8 | |

| Post-Vietnam | 10 | 28.6 | 8 | 18.6 | 22 | 18.8 | |

| Persian Gulf | 10 | 28.6 | 9 | 20.9 | 25 | 21.4 | |

| Fair/poor health status | 12 | 34.3 | 20 | 47.6 | 45 | 45.3 | 0.44 |

| Worse health compared with 1 year ago | 11 | 31.4 | 15 | 35.7 | 45 | 38.5 | 0.74 |

| Number of comorbid conditions | 0.49 | ||||||

| 0–1 | 10 | 29.4 | 6 | 14.0 | 26 | 22.2 | |

| 2–3 | 10 | 29.4 | 16 | 37.2 | 45 | 38.5 | |

| 4+ | 14 | 41.2 | 21 | 48.8 | 46 | 39.3 | |

| Confidence with medical forms | 0.58 | ||||||

| Not at all/a little bit/somewhat | 3 | 9.1 | 7 | 16.3 | 18 | 15.4 | |

| Quite a bit | 7 | 21.2 | 4 | 9.3 | 20 | 17.1 | |

| Extremely | 23 | 69.7 | 32 | 74.4 | 79 | 67.5 | |

| Eligibility | 0.001 | ||||||

| Distance only | 27 | 77.1 | 32 | 74.4 | 58 | 49.6 | |

| Wait time only | 1 | 2.9 | 4 | 9.3 | 5 | 4.3 | |

| Distance and wait time | 7 | 20.0 | 7 | 16.3 | 54 | 46.2 | |

*Attempted but had not received Choice care

GED general equivalency diploma, VA Department of Veterans Affairs

Sociodemographic or clinical characteristics did not vary significantly by Choice user status (Table 1). However, there were differences in eligibility for the Choice program. Compared with those who did not attempt to use Choice or who attempted only, Veterans who received Choice care were more likely to be eligible for Choice due to both distance and wait time (20.0% and 16.3% versus 46.2%; p < 0.001).

Ratings of Satisfaction with VA Health Care and Choice

Most participants reported being somewhat or very satisfied with VA health care, including 85.3% of participants who did not attempt to use Choice, 72.1% of participants who attempted only, and 71.1% of participants who had attempted and received Choice care (Table 2). VA satisfaction was greater for participants eligible due to distance only (81.9%) or wait times only (80.0%) versus distance and wait times (58.5%, p = 0.01). Regarding satisfaction with Choice, 17.9% of participants who attempted only reported being somewhat/very satisfied with Choice, compared with 66.7% of those who had attempted and received Choice care (Table 2); 53.8% of participants who attempted only reported being very dissatisfied with the program (data not tabled).

Table 2.

Ratings of Satisfaction with VA Health Care and the Veterans Choice Program, by Attempt and Receipt of Care in the Choice Program in 2015

| Attempt and receipt of care under the Veterans Choice Program | p value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No attempt | Attempted only* | Received Choice care | |||||

| N † | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Satisfaction with VA health care (n = 191) | 0.06 | ||||||

| Very satisfied | 12 | 35.3 | 12 | 27.9 | 42 | 36.8 | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 17 | 50.0 | 19 | 44.2 | 39 | 34.2 | |

| Less than satisfied | 5 | 14.7 | 12 | 27.9 | 33 | 29.0 | |

| Satisfaction with Choice (n = 153)‡ | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Very satisfied | 2 | 5.1 | 45 | 39.5 | |||

| Somewhat satisfied | 5 | 12.8 | 31 | 27.2 | |||

| Less than satisfied | 32 | 82.1 | 38 | 33.3 | |||

*Attempted but had not received Choice care

†N indicates the number of valid responses. Non-Likert responses (e.g., do not know, not applicable) were treated as missing

‡Satisfaction with Choice was assessed only for those who attempted to use Choice

Within-subject comparisons of satisfaction ratings for VA health care and Choice care differed by Choice receipt of care status (Table 3). Participants who attempted only were less likely to be somewhat/very satisfied with Choice than with VA health care (17.9% versus 71.8%, p < 0.001 for symmetry and marginal homogeneity). Those who had attempted and received Choice care were equally likely to be somewhat/very satisfied with Choice as with VA health care (66.7% versus 71.2%, p = 0.59 for symmetry and p = 0.46 for marginal homogeneity).

Table 3.

Comparison of Satisfaction with VA Health Care and the Veterans Choice Program, by Attempt and Receipt of Care in the Choice Program in 2015

| Satisfaction with VA health care | Satisfaction with Choice | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very satisfied | Somewhat satisfied | Less than satisfied | ||

| Attempted but had not received Choice care (n = 39)* | ||||

| Very satisfied | 0 | 2 | 10 | 12 (30.8%) |

| Somewhat satisfied | 2 | 3 | 11 | 16 (41.0%) |

| Less than satisfied | 0 | 0 | 11 | 11 (28.2%) |

| Total | 2 (5.1%) | 5 (12.8%) | 32 (82.1%) | 39 (100%) |

| p < 0.001† | ||||

| Attempted and received Choice care (n = 111) | ||||

| Very satisfied | 24 | 7 | 10 | 41 (36.9%) |

| Somewhat satisfied | 12 | 13 | 13 | 38 (34.2%) |

| Less than satisfied | 8 | 10 | 14 | 32 (28.8%) |

| Total | 44 (39.6%) | 30 (27.0%) | 37 (33.3%) | 111 (100%) |

| p = 0.59 and 0.46† | ||||

*Within-subject cross-tabulation of satisfaction with VA health care and satisfaction with the Veterans Choice Program, conducted separately for participants who attempted but had not received Choice care (n = 39) and for participants who received Choice care (n = 111)

†p values obtained from tests of symmetry and marginal homogeneity, respectively. p’s < .05 indicate a within-subject difference in ratings of satisfaction with VA health care compared with ratings of satisfaction with Choice

Reasons for Choice Satisfaction Rating, by Receipt of Care Status

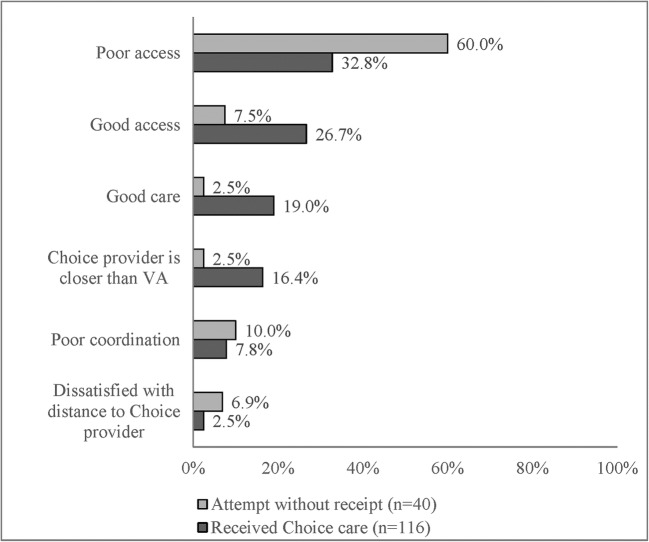

When asked what contributed to their rating of the Choice program, participant responses indicated areas of dissatisfaction and satisfaction. The three most frequent dissatisfaction and satisfaction codes, respectively, are provided in Figure 1 in descending order of frequency. Participants who attempted but had not received Choice care were more likely to report dissatisfaction related to poor access (60.0% versus 32.8% for those who received Choice care) and poor coordination (10.0% versus 7.8%) as factors contributing to their Choice rating. Participants who received Choice care were more likely to report satisfaction related to easy/improved access (26.7% versus 7.5% for those who attempted only), good care from Choice providers (19.0% versus 2.5%), and satisfaction with location of Choice providers (16.4% versus 2.5%).

Figure 1.

Reasons for satisfaction with Choice for participants who attempted but had not received Choice care ( n = 43) and those who received Choice care ( n = 117). The reported reasons were derived from a qualitative analysis of responses to the question “What contributed to your overall rating for the Choice Program?” The top three satisfaction and dissatisfaction codes from the qualitative analysis are presented in descending order of frequency.

Thematic Analysis of Choice Interviews

A more detailed qualitative analysis of the telephone interviews identified specific areas of dissatisfaction and satisfaction with Choice. The most frequently reported themes are summarized in Table 4 and supported by illustrative quotations in Appendix 3 in the ESM.

Table 4.

Themes of Dissatisfaction and Satisfaction with the Choice Program for Veterans by Attempt and Receipt of Care in the Choice Program in 2015

| Dissatisfaction and satisfaction themes* | Number (%) of participants who mentioned themes, by attempt and receipt of Choice care† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attempted only† (n = 43) | Received Choice care (n = 117) | |||

| n ‡ | % | n | % | |

| Dissatisfaction | ||||

| Scheduling appointments | 15 | 34.9 | 59 | 50.4 |

| Lack of information | 12 | 27.9 | 51 | 43.6 |

| Poor coordination of services | 6 | 14.0 | 41 | 35.0 |

| Difficulty obtaining authorization | 9 | 20.9 | 34 | 29.1 |

| Red tape | 11 | 25.6 | 30 | 25.6 |

| Lack of Choice provider | 11 | 25.6 | 22 | 18.8 |

| Third-party administrator | 4 | 9.3 | 25 | 21.4 |

| Enrollment problems | 9 | 20.9 | 21 | 17.9 |

| Long distance to Choice provider | 6 | 14.0 | 14 | 12.0 |

| Billing problems | 2 | 4.7 | 17 | 14.5 |

| Satisfaction | ||||

| Distance to Choice provider | 26 | 60.5 | 92 | 78.6 |

| Easy scheduling appointments | 5 | 11.6 | 40 | 34.2 |

| Short time to see provider | 3 | 7.0 | 24 | 20.5 |

| Saw preferred provider | 2 | 4.7 | 19 | 16.2 |

| Easy enrollment | 2 | 4.7 | 13 | 11.1 |

| Had a good Choice provider | 2 | 4.7 | 12 | 10.3 |

*Dissatisfaction and satisfaction themes that emerged from thematic analysis of audio-recorded interviews. Themes reported by at least 5% of participants are reported in descending order of frequency

†Attempted but had not received Choice care

‡The n and % columns present the number and percentage of respondents who provided at least one statement during the interview with the dissatisfaction/satisfaction code

Dissatisfaction Themes

Regardless of whether participants ultimately received Choice care, a frequently reported theme of dissatisfaction pertained to appointment scheduling through third-party administrators. Participants who attempted only (34.9%) and those who received Choice care (50.4%) described an inefficient scheduling process that resulted in multiple phone calls and lengthy appointment wait times. Both groups also expressed dissatisfaction with the lack of information about Choice (27.9% and 43.6%, respectively), such as receiving mailings indicating their eligibility for Choice that contained little information about how to use the program. Problems were exacerbated when third-party administrators provided incomplete or inaccurate information when participants called.

Other prominent dissatisfaction themes included difficulties with obtaining authorization for non-VA care (20.9% and 29.1% among Choice attempters and users, respectively), “red tape” associated with Choice (25.6% for each), and lack of Choice providers (25.6% and 18.8%). Some dissatisfaction themes applied primarily to participants receiving Choice care, such as problems with care coordination (35.0%), dissatisfaction with third-party administrators (21.4%), and billing problems (14.5%).

Satisfaction Themes

The most common satisfaction theme related to travel distance (60.5% and 78.6% among participants who attempted only or received care, respectively; Table 4). Many of these participants described the convenience of having a provider close to their home.

The remaining satisfaction themes applied primarily to participants who received Choice care. Some of these participants had an easy time getting an appointment and reported satisfaction in this area (34.2%). Some participants who received Choice care expressed satisfaction related to short wait times (20.5%), seeing a preferred provider (16.2%), or having a good experience with their Choice provider (10.3%).

Responses to Specific Interview Questions

Reasons for Not Using Choice

Of the participants who never attempted to use Choice (n = 33), some reported that they just learned about the program and did not know they were eligible. Others did not want to experience the potential hassle of enrolling in a new program and finding a participating provider.

Intentions to Use Choice in the Future

Most participants (80.0% of those who had not attempted to use Choice, 69.8% of those who attempted only, 82.1% of those who had attempted and received care) reported they might or would use Choice in the future. Participants discussed the value of reduced travel distance and appointment wait times, and acknowledged that the Choice program was new and could improve with time.

Access Following Choice

Finally, we asked participants who received Choice care if the program had improved their access to care. While 48.7% reported that the program had improved their ability to obtain care, 23.1% reported no change, and 20.5% reported the program had worsened their ability to obtain care.

DISCUSSION

Our concurrent mixed-method study was designed to compare Veterans’ satisfaction with health care options and experiences in the early implementation phase of the Veterans Choice Program. In a sample of Veterans with substantial access barriers, we observed generally high levels of satisfaction with VA health care overall, with the greatest satisfaction reported in Veterans not attempting to use the Choice program. In contrast to the patterns of satisfaction with VA health care, a high percentage of participants were less than satisfied with experiences of care under Choice; we observed the lowest satisfaction ratings in those who attempted but had not received care through this new program. Our thematic analysis of qualitative interviews revealed that scheduling processes, lack of information about Choice, poor coordination, red tape, and difficulty obtaining authorizations were the main factors contributing to dissatisfaction.

Our study builds on prior research characterizing Choice implementation challenges19–21 by identifying sources of satisfaction and dissatisfaction with Choice in a geographically diverse sample of Veterans attempting to use Choice, and by examining the perspectives of eligible Veterans who have not attempted to use Choice. One qualitative study of Veterans with chronic Hepatitis C virus reported problems with Choice enrollment, appointment scheduling, billing with third-party administrators, and inadequate provider networks.5 A second qualitative study, which interviewed Veterans who attempted to use Choice, found that lack of local providers and poor coordination between the VA and third-party administrators were key barriers to accessing care through Choice.6 Our study identified these programmatic barriers as major sources of dissatisfaction. Our interviews also revealed that eligible Veterans did not attempt to use Choice due to lack of information and perceptions that Choice was difficult to navigate. A targeted information campaign could help eligible Veterans to learn about their health care options.

Our finding that dissatisfaction with Choice was greatest for Veterans who attempted unsuccessfully to receive Choice care has implications for ongoing program evaluations and future research. While the VA is tracking performance on measures of patient experiences following receipt of Choice care, no systematic efforts have been made to assess the barriers faced by Veterans who are unsuccessful in accessing Choice services. The perspective of Veterans who did not receive Choice care is needed to understand what barriers are keeping Veterans from obtaining the care they seek. In the present study, many of the Veterans without a Choice claim in administrative records reported prior attempts to use Choice and expressed interest in trying to use Choice in the future. Involving those who administer Choice enrollment and appointment scheduling in future evaluations of Veteran experiences with Choice may help to identify Veterans who experience access barriers, and to better understand reasons for not using Choice.

While areas for improvement remain, our results indicate that Choice is meeting the expectations of many Veterans with barriers to conventional VA care. For example, our analysis of qualitative satisfaction themes highlighted aspects of Choice that resulted in positive satisfaction ratings among Veterans who succeeded in obtaining Choice care, such as reduced travel distance, shorter wait times, and good experiences with non-VA providers. Half of Choice users perceived their ability to get appointments improved under Choice, and most participants expressed a willingness to use Choice in the future.

We note that the VA is working to address many of the areas of dissatisfaction identified in our interviews: scheduling appointments, lack of information on Choice, coordination of services, obtaining pre-authorization for care, and lack of Choice providers near Veterans. Efforts are underway to establish formal communication systems between VA and non-VA providers and optimize non-VA provider networks in the communities where Veterans live. Additionally, Congress recently passed the VA Maintaining Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act, which consolidates the VA’s community care programs (including Choice), creates an education program to give Veterans information about their health care options, and trains VA contractors to improve the administration of non-VA health care programs. As more Veterans seek health care outside of VA facilities, it will be important for prospective studies to assess whether satisfaction with scheduling, information, care coordination, and choice of local providers improve with policy changes.

This study has limitations. First, our sample includes some of the first Veterans to experience the Choice rollout, and the satisfaction/dissatisfaction findings may not generalize to Veterans using Choice more recently. Second, our study sites were 25 VA medical centers serving relatively large proportions of racial/ethnic minority Veterans; the demographic composition of respondents may not be representative of Choice-eligible Veterans nationally. Because most Veterans eligible by wait time were also eligible by distance, our final sample included few participants eligible due to wait times only. Third, we observed modest survey response rates overall, and lower than expected participation among Veterans eligible based on wait times only and those who had not used Choice. Consequently, we had limited power to detect potential differences in VA satisfaction among the non-users who had attempted or not attempted to use Choice. This is an important avenue for future research, as Veterans with less positive VA health care experiences may be the ones attempting to use Choice. Finally, small numbers limited our ability to address potential confounding in multivariable models. Except for eligibility, participant characteristics do not appear to differ substantially by Choice user status. Despite limitations, our study does shed light on barriers and facilitators that emerged from VA health care system changes, which can be important to document as the VA continues to reevaluate the Choice program. These findings demonstrate the attitudes of patients who are exposed to a new model of care and may be useful as comparators for emerging changes under the MISSION Act.

In summary, this mixed methods evaluation highlights challenges and opportunities presented by the Veterans Choice Program in the first year of implementation. We identified programmatic barriers that contributed to dissatisfaction among Veterans who were unsuccessful in attempts to use the new program. Importantly, satisfaction with Choice improved and was on par with satisfaction for VA health care overall when patients overcame these early access challenges. Collectively, our findings indicate that health policy changes that enable Veterans to receive care in the community are valued by Veterans who have difficulty accessing traditional VA health care. As the VA and U.S. Congress consolidate health care initiatives under the MISSION Act, continued efforts are needed to address the health care barriers that prevent Veterans from receiving care in the community.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 39 kb)

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (VCA 15-245); the VA Office of Academic Affiliations Post-Doctoral Fellowship in Medical Informatics (TMI 95-660); and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR002538 and KL2TR002539.

Dr. Vanneman would like to acknowledge research support from the University of Utah Health Enhancing Development-Generating Excellence (EDGE) and Vice President’s Clinical and Translational (VPCAT) scholar programs.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The VA Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved this study as a quality improvement project.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The contents of this article do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the United States Government, University of Pittsburgh, or University of Utah.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hicks J. A guide to the VA health care controversy. The Washington Post. March 15, 2014

- 2.Mattocks KM. Care coordination for women veterans: Bridging the gap between systems of care. Med Care. 2015;53(4 Suppl 1):S8–9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.VA Office of Inspector General. Veterans Health Administration review of the Implementation of the Veterans Choice Program. Office of Audits and Evaluations, Jan 30 2017. 15-04673-333.

- 4.Vanneman ME, Harris AH, Asch SM, Scott WJ, Murrell SS, Wagner TH. Iraq and Afghanistan veterans’ use of Veterans Health Administration and purchased care before and after Veterans Choice Program implementation. Med Care. 2017;55(7 Suppl 1):S37–S44. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai J, Yakovchenko V, Jones N, et al. “Where’s my choice?” An examination of veteran and provider experiences with hepatitis C treatment through the Veteran Affairs Choice Program. Med Care. 2017;55(7 Suppl 1):S13–S19. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sayre GG, Neely EL, Simons CE, Sulc CA, Au DH, Michael Ho P. Accessing care through the Veterans Choice Program: the veteran experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(10):1714–1720. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4574-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGinnis KA. Capsule commentary on Zickmund et al., racial, ethnic, and gender equity in veteran satisfaction with health care in the Veterans Affairs health care system. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(3):333. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4253-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Creswell JW, Fetters MD, Ivankova NV. Designing a mixed methods study in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(1):7–12. doi: 10.1370/afm.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zickmund S, Burkitt K, Gao S, et al. Racial, ethnic, and gender equity in veteran satisfaction with health care in the Veterans Affairs health care system. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(3):305–331. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4221-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandelowski M. Sample size in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health. 1995;18(2):179–183. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damschroder LJ, Lowery JC. Evaluation of a large-scale weight management program using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) Implement Sci. 2013;8:51. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):561–566. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaudhry S, Jin L, Meltzer D. Use of a self-report-generated charlson comorbidity index for predicting mortality. Med Care. 2005;43(6):607–615. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163658.65008.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM. The RAND 36-item health survey 1.0. Health Econ. 1993;2(3):217–227. doi: 10.1002/hec.4730020305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowker AH. A test for symmetry in contingency tables. J Am Stat Assoc. 1948;43(244):572–574. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1948.10483284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maxwell AE. Comparing the classification of subjects by two independent judges. Br J Psychiatry. 1970;116(535):651–655. doi: 10.1192/bjp.116.535.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller W. B. C. Primary care research: A multi typology and qualitative road map. In: Crabtree B, Miller W, editors. Doing qualitative research. London: Sage; 1992. pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mattocks KM, Mengeling M, Sadler A, Baldor R, Bastian L. The Veterans Choice Act: A qualitative examination of rapid policy implementation in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2017;55(7 Suppl 1):S71–S75. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finley EP, Noel PH, Mader M, et al. Community clinicians and the Veterans Choice Program for PTSD care: Understanding provider interest during early implementation. Med Care. 2017;55(7 Suppl 1):S61–S70. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gellad WF, Cunningham FE, Good CB, et al. Pharmacy use in the first year of the Veterans Choice Program: A mixed-methods evaluation. Med Care. 2017;55(7 Suppl 1):S26–S32. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 39 kb)