Abstract

Background

Psychomotor agitation and aggressiveness in the context of mental illness are medical emergencies. In a survey of six German psychiatric hospitals, 1.7 to 5 aggressive attacks per patient-year were reported. If talking to the patient has no calming effect, intervention with drugs is required. In this article, we review the evidence on tranquilizing drugs and discuss clinically relevant ethical and practical questions, e.g., with respect to involuntary medication.

Method

This review is based on pertinent articles retrieved by a selective search in MEDLINE, supplemented by a reference search.

Results

The evidence for the treatment of psychomotor agitation with antipsychotic drugs and benzodiazepines is relatively good. Randomized, controlled trials and a number of Cochrane reviews are available. These publications, however, contain data only on patients who were able to give informed consent. Their findings are often not applicable to real-life emergencies, e.g., when the patient is intoxicated with alcohol or suffers from a pre-existing disease. Haloperidol has a relatively weak effect on aggression when given alone and can also cause side effects such as early dyskinesia and epileptic seizures. It should, therefore, no longer be used as monotherapy. On the other hand, haloperidol combined with benzodiazepines or promethazine and monotherapy with lorazepam, olanzapine, ziprasidone, or aripiprazole intramuscular are effective options for the treatment of aggressive psychomotor agitation.

Conclusion

All of these drugs, if accepted by the patient, can also have an additional, beneficial placebo effect, with the patient calming down more rapidly than could be explained on pharmacological grounds alone. It is, therefore, important in emergencies (as at other times) for the patient to be involved in treatment decisions to the greatest possible extent.

Aggressive behavior can be considered pathological only when it arises in the context of disease. It is thus not necessarily an indication for medical treatment. Not only emergency medical personnel and psychiatrists, but also family physicians are often confronted with the question of how to treat aggressive behavior. In one study, psychiatric emergencies accounted for 11.8% of all emergency medical interventions outside the hospital. Psychomotor agitation made up 28% of all psychiatric emergencies, second only to alcohol intoxication (33%) (1).

Psychomotor agitation in the context of mental illness and intoxication constitutes a medical emergency. Affected patients can injure themselves or others. In a retrospective survey of six German psychiatric hospitals, 1.7 to 5 aggressive attacks per patient-year were reported (2). In one hospital in the federal state of North Rhine–Westphalia, 171 of the 2210 patients admitted within a 1-year period were involved in aggressive attacks, and a total of 441 episodes of aggressive behavior were reported (3).

Psychomotor agitation carries the risk of somatic complications, including electrolyte disturbances, rhabdomyolysis, and lactic acidosis (4, 5). The goal of pharmacotherapy is to calm the patient. Amnesia and deep sedation should be avoided in order not to compromise the patient’s ability to participate in joint decision-making about further treatment. Deep sedation also puts patients at risk of cardiorespiratory depression, aspiration, and other complications. No data on this topic are available from Germany, but an Australian study has shown that 16 agitated patients who were pharmacologically sedated (9% of the patients so treated) sustained complications such as hypotension and hypoxemia (6).

The health-related causes of aggressive behavior include nearly all kinds of mental disorders, and various somatic illnesses as well. In an emergency, the history should be rapidly obtained from someone who has observed the behavior, and an initial, orienting physical examination should be performed. Intoxications, withdrawal syndromes, a postictal state, and rapidly reversible causes such as hypoglycemia should be ruled out (7).

The patient’s permission for pharmacotherapy should be obtained whenever possible. In Germany, when the patient refuses treatment, the physician must determine whether coercive emergency treatment is permissible and required, as per the concept of a “justifying emergency” under federal law (§ 34 German Criminal Code) and the corresponding provisions of the laws on assistance to the mentally ill of the individual German states. The danger to the patient and others in the absence of treatment must be weighed against the violation of the patient’s autonomy by coercive treatment. In this review, we discuss the ways in which states of psychomotor agitation with aggression can be treated effectively and safely.

Method

The MEDLINE database was searched for relevant articles that appeared from January 2006 to September 2008 (for the search terms used, see eTable). Other publications retrieved by the literature search for the recently issued German clinical practice guideline on the prevention of coercive measures in psychiatry (7) were considered as well. Since the publication of that guideline, the evidence base has expanded to included data on loxapine, an inhaled antipsychotic drug (8, 9), and on ketamine, a narcotic (10).

Studies on rapid tranquilization were included in the analysis. Randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses were included, as well as observational studies and retrospective analyses, e.g., for the evaluation of drug safety. Literature screening for the present article was carried out by two persons (SH and RG) working independently of one another. Any discordant evaluations were settled by joint consideration of the article in question.

Results

The evidence from clinical studies mainly concerns intramuscularly administered drugs. Only a few studies have dealt with the efficacy of orally administered drugs in emergencies.

RCTs and Cochrane reviews are available for many of the substances currently in use (11– 16), but these publications usually concern the drug treatment of agitated patients in general. For easily understandable reasons, high-quality studies on genuine emergencies, e.g., those in which coercive treatment may be required after a physical attack, are lacking. It would be impossible, for example, to obtain legally valid informed consent from patients for participation in such a study.

An overview of dosage recommendations for adults is provided in Table 1. Lower doses must be used in elderly patients. For most drugs, no data on their use in the elderly are available from RCTs. Manufacturers’ recommendations are available only for haloperidol and olanzapine: the dose of each in elderly patients should be about half of the lowest amount given to adults in younger age groups (e1, e2).

Table 1. Dosage recommendations for parenterally administered drugs for the treatment of psychomotor agitation.

| Drug preparation |

Dosage recommendation in psychosis |

Dosage recommendation for patients over age 60 |

Repetition | Duration |

Maximum dose in 24 h |

Relative risk for no improvement of agitation compared with placebo (from the literature) |

| Aripiprazole 7.5 mg/mL solution for injection | Initially 9.75 mg i. m. |

No information/ not recommended |

One to two times in 24 h at an interval of at least 2 h |

No information | 30 mg*1 | RR 0.49 95% CI [0.34; 0.71] after one injection (12) |

| Haloperidol solution for injection |

Initially 5–10 mg i. m. |

Initially 0.5–1.5 mg, max. 5 mg/d |

No information | No information | 60 mg | RR 0.88 95% CI [0.82; 0.95] after 2 h (14) |

| Lorazepam solution for injection |

Initially 0.05 mg per kg slowly i. v. (or i. m.) *2 |

No information | The same dose can be given again 2 h later if necessary |

Only short-term adjuvant treatment |

No information |

RR 0.62 95% CI [0.40; 0.97] after 48 h (for benzodiazepines in general) (16) |

| Loxapine powder in individual doses for inhalation*3 |

Initially 9.1 mg by inhalation |

No information/ not recommended |

Once in 24 h with an interval of at least 2 h between doses |

At most two treatments, then Initiation of regular therapy |

18.2 mg | – |

| Olanzapine powder for production of a solution for injection |

Initially 10 mg or lower i. m. |

Initially 2.5–5 mg 2.5–5 mg after 2 h; max. 3 inj/d, max. 20 mg/d *1 |

5–10 mg after 2 h, max. 3 inj/d |

Up to 3 d | 20 mg*1 | RR 0.49 95% CI [0.42; 0.59] after two h, resp. NNT 4 95% CI [3; 5] (13) |

| Promethazine solution for injection |

Initially 25 mg (slowly, max. 25 mg/min) i. m. or i. v. |

No information | Repeat in 2 h; if there is still no effect 50–100 mg/d |

A few days | 200 mg | In combination with haloperidol, compared to haloperidol alone, after 30 min RR 0.65 95% CI [0.49; 0.87] (11) |

| Ziprasidone powder for production of a solution for injection |

Initially 10(–20) mg i. m. |

i. m. administration not recommended for these patients |

10 mg every 2 h *4 |

Up to 2 d | 40 mg | No placebo-controlled studies of out come when given to treat psychomotor agitation/unrest |

*1 For any mode of administration.

*2 Caution: i. v. only with diluted solution!

*3 May only be given in a hospital under the supervision of medical staff; bronchodilating therapy with a ß2-mimetic drug must be available in case it is needed.

*4 If 20 mg is given initially, the next dose should be 10 mg, given no sooner than 4 h later; continue with another 10 mg a further 2 h later (excerpt from [e3])

i. m., intramuscular; inj, injection; i. v.; intravenous; NNT, number needed to treat; RR, relative risk; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

Antipsychotic drugs are no longer approved for intravenous administration because of their adverse cardiac effects (torsade de pointes) and are thus given by deep intramuscular injection. For ethical reasons, coercive removal of the patient’s clothes should be avoided. Intramuscular injection is contraindicated in anticoagulated patients. Benzodiazepines are approved for intravenous use and may be a good alternative. An overview of the approval status and direct healthcare professional communications on the substances in question is provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Approval status and relevant “Red-Hand Letters*1” for parenterally administered drugs for the treatment of psychomotor agitation.

| Preparation | Approval status | Administration | Red-Hand Letter |

| Aripiprazole 7.5 mg/mL solution for injection |

Approved only to control agitation and behavioral disturbance in patients with schizophrenia or mania as a component of bipolar I disorder Not approved to treat psychosis or agitation/behavioral disturbance in patients with dementia or other diseases |

i. m. | Red-Hand Letter, 2005 Dose-dependent elevation of the frequency of cerebrovascular events in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia |

| Haloperidol solution for injection |

Approved to treat psychomotor agitation of psychotic origin |

i. m. | – |

| Lorazepam solution for injection |

Baseline sedation before and during operations and diagnostic procedures; for severe manifestations of neurotic anxiety and phobia; for severe anxiety and agitation in patients with psychosis or depression, if treatment with antipsychotic or antidepressant drugs is ineffective; for status epilepticus |

i. v. or i. m. |

– |

| Loxapine powder in individual doses for inhalation *2 |

For mild to moderate agitation in adult patients with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder |

by inhalation | – |

| Midazolam solution for injection*3 |

For analgosedation, general anesthesia, and sedation in the intensive-care unit |

i. v. (for children also i. m., rectal) |

– |

| Olanzapine powder for production of a solution for injection |

For the rapid treatment of agitation and behavioral disturbance in schizophrenia or manic episodes Not approved to treat psychosis or agitation/behavioral disturbance in patients with dementia or other diseases |

i. m. | Red-Hand Letter, 2004 Doubled mortality and trebled incidence of cerebrovascular events in elderly patients treated for dementia-associated psychosis and agitation/behavioral disturbance |

| Promethazine solution for injection |

For acute allergic reactions of the immediate type, if sedation is required at the same time; for acute states of unrest and agitation in the context of an underlying mental illness Not approved for the treatment of behavioral disturbances in the the context of dementia |

i. v. or i. m. |

– |

*1 In Germany, these letters are used by pharmaceutical companies to communicate important information to medical professionals, e.g., newly discovered adverse effects of drugs or batch recalls.

*2 May only be given in a hospital under the supervision of medical staff; bronchodilating therapy with a ß2-mimetic drug must be available in case it is needed.

*3 No psychiatric indication stated.

i.m., intramuscular; i. v., intravenous

In the following sections, we will discuss each of the various substance classes individually. If the patient does not cooperate at all, the physician will have to use parenterally administrable formulations. For many years, first-generation antipsychotic drugs such as haloperidol were used for this purpose. Since second-generation antipsychotics have become available for parenteral use, they have also been used in these indications. Because of the potential adverse effects of antipsychotic drugs, benzodiazepines are increasingly being used as monotherapy. Studies from the field of emergency medicine have recently dealt more intensively with the use of ketamine.

Emergency medication for uncooperative patients

First-generation antipsychotic drugs – haloperidol

The best evidence is available for the treatment of aggressive psychomotor agitation with a combination of haloperidol and promethazine. In six RCTs, this combination was tested against monotherapy with midazolam, lorazepam, olanzapine, ziprasidone, and haloperidol, and against the combination of haloperidol and midazolam (11). Haloperidol as monotherapy has been studied in a total of 41 RCTs: it was found to be superior to both placebo and aripiprazole, but there was no significant difference from monotherapy with lorazepam (14). With the combination of haloperidol and promethazine, fewer additional injections are needed than with monotherapy. The proportion of patients who were still agitated 30 minutes after injection was also markedly lower than after monotherapy (relative risk [RR] 0.65; 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.49; 0.87]) (12). Unlike benzodiazepine treatment, this combination did not induce respiratory depression.

The use of haloperidol for monotherapy is now increasingly discouraged because of its poor efficacy and undesired side effects (dystonia, epileptic seizures) (11, 17). The use of promethazine in combination with haloperidol can counteract dystonia, but the current manufacturers’ recommendations state that haloperidol should no longer be given together with other medications that prolong the QTc interval, such as promethazine. There is thus a discrepancy between the findings of studies from multiple countries documenting the superiority of combination therapy over monotherapy because of its better safety profile, at least in physically healthy, non-intoxicated patients, and the approval policies of the manufacturers, who recommend against combination therapy (e1).

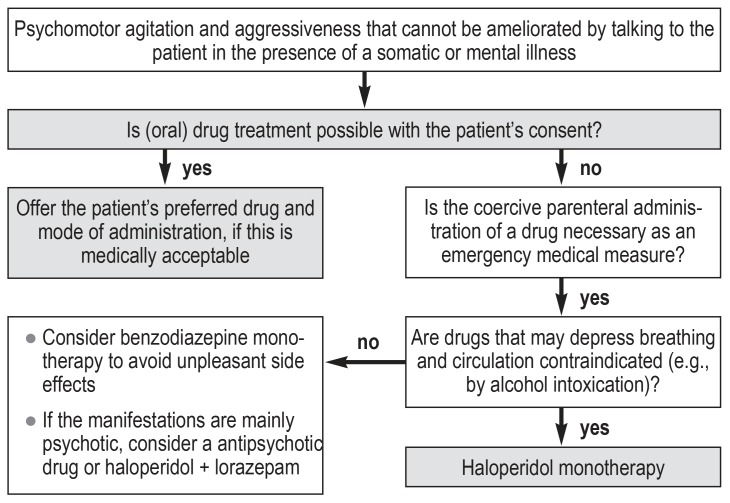

The combination of haloperidol with lorazepam, though commonly used in Germany, does not lessen extrapyramidal side effects (17). Because it is not very sedating, monotherapy with haloperidol continues to play an important role in the treatment of intoxicated patients and of patients with severe somatic diseases (figure).

Figure.

Algorithm to help select the drug type and mode of administration in the treatment of psychomotor agitation and aggressive behavior

Second-generation antipsychotics

In one RCT, ziprasidone was found to counteract aggressive behavior better than the following drugs and drug combinations (17):

Haloperidol plus promethazine

Haloperidol plus midazolam

Haloperidol monotherapy

Olanzapine

According to a review, ziprasidone and olanzapine had a lower number needed to treat (NNT = 3) than aripiprazole (NNT = 5; [18]). Nonetheless, ziprasidone is not yet commonly used in psychiatric emergency care, presumably because of its minimal sedating effect and only mild antipsychotic action (19). Compared with aripiprazole, olanzapine was superior initially, probably because of its sedating effect; 24 hours later, there was no longer any significant difference (12, 13, 20, 21).

Olanzapine is sedating and, therefore, may intuitively seem suitable for the treatment of aggressive psychomotor agitation. Olanzapine for psychomotor agitation was tested in eight RCTs: it was found superior to placebo in four trials, with NNT = 4 (95% CI [3; 5]), and comparably effective to haloperidol or lorazepam in a further four trials (two for the comparison with each drug) (13). Nonetheless, in a retrospective pharmacovigilance study including an evaluation of 160 reports after the initial marketing of a rapidly-acting olanzapine formulation for intramuscular injection, 29 deaths were documented. Olanzapine was combined with benzodiazepines in 66% of these cases, and with other antipsychotics in 76%. In the period in which this pharmacovigilance study was carried out, some 539 000 persons worldwide were treated with intramuscular olanzapine (22). In a retrospective study performed in 2012, the combination of olanzapine and benzodiazepines was found to cause respiratory depression in alcohol-intoxicated patients (23).

Thus, olanzapine should not be given parenterally in combination with benzodiazepines because of the potentially life-threatening adverse effects. Before giving olanzapine intramuscularly, the physician must decide, if the patient can be treated safely without using benzodiazepines at least in the short and medium term. The emergency use of olanzapine is thus practically limited to non-intoxicated patients with a known psychotic disease who have already responded to olanzapine in the past.

Lorazepam and other benzodiazepines

In a Cochrane review covering 20 RCTs, benzodiazepine monotherapy was not found superior to placebo to any statistically significant extent, nor was it found inferior to the antipsychotic drugs or to the combination treatments discussed above to any statistically significant extent (16). Midazolam should not be used for psychiatric indications because of the increased risk of respiratory depression.

The question whether benzodiazepines, antipsychotic drugs, or a combination of the two should be used to treat aggressive psychomotor agitation has been discussed in the psychiatric literature for many years. The database remains inadequate. In patients with known psychotic illness, it may be reasonable to use an antipsychotic drug right away in the emergency situation (24). Benzodiazepines should not be given over the long term to patients with recurrent aggressive behavior, as their regular use is associated with an increase in such behavior (25), as well as with habituation and addiction.

In an RCT comparing haloperidol plus lorazepam with lorazepam as monotherapy, the combination was found to be more effective against aggressive and hostile behavior 60 minutes after administration (NNT = 3). There were no significant differences in the clinical (psychotic) manifestations (26). It remains unclear whether the better effect of combined treatments might alternatively be obtained simply by giving a single substance at a higher dose.

Benzodiazepines are approved for intravenous administration. In emergency situations, they are an important alternative to antipsychotic drugs for treatment without the patient’s consent. A potentially helpful flowchart for the selection of drug class and mode of administration is provided (see Figure).

Ketamine

Ketamine is used in emergency medicine for the induction of dissociative anesthesia, i.e., adequate sedation without depression of the airway-protective reflexes. In a recent review, studies on the pre-hospital use of ketamine for patients with agitation and aggressiveness were evaluated. In one study, ketamine was compared with haloperidol; in another, ketamine was compared with haloperidol in combination with either a benzodiazepine or an antihistamine. Ketamine was found to have a faster onset of action than haloperidol, with sedation beginning 5 minutes after administration (17 minutes for haloperidol). Protective intervention became necessary in 39% of patients in the ketamine group because of hypersalivation or vomiting (9).

In a further retrospective study, it was found that patients who receive ketamine need intubation more frequently, and they also often need haloperidol and benzodiazepines in their further course (27). The two studies just mentioned were published too late to be included in the analysis for the current clinical practice guideline. However, from a psychiatric point of view the use of ketamine can not be recommended even based on the moset recent data.

Emergency medication in patients with limited compliance

Drugs should be administered with the patient’s consent whenever possible. Consent enables the drug to be given by the oral rather than the intramuscular or intravenous route. In such situations, successful cooperation is more important than the more rapid onset of an intravenously administered drug, and cooperation between patient and physician itself is therapeutically effective. These aspects are increasingly being considered in discussions of the autonomy of patients with mental illness and of persons with mental and cognitive disability. Oral administration is easier than it once was, as many antipsychotic drugs now come in rapidly-acting formulations such as liquids, dissolving (orodispersible) tablets, and inhalations.

Antipsychotic drugs for oral administration

In an RCT, the oral administration of risperidone 2 mg combined with lorazepam 2 mg was found comparably effective to the intramuscular administration of haloperidol 5 mg combined with lorazepam 2 mg. In this trial, hostility and tension were measured on a single scale; the 95% CI of all mean values and changes over time in the two groups overlapped at all measurement times (28). In another randomized trial, agitation in patients with psychotic disorders responded significantly better in the first 90 minutes to olanzapine, given either by intramuscular injection or orally as a dissolving tablet, than to intramuscular haloperidol (29). There was no significant difference at later times.

In another trial, oral formulations of olanzapine, haloperidol, and risperidone were compared. None of these drugs was found to be significantly superior to the others (30), so the choice of drug can be based on the adverse-effect profile and the patient’s preferences. A review of six RCTs on orally administered antipsychotic drugs for the treatment of psychomotor agitation led to the conclusion that these are all comparably effective to haloperidol and to parenteral formulations (31). Sublingually administered asenapine was also found to be effective against agitation in a placebo-controlled trial, with an NNT of 3 (95% CI [2; 4]), similar to that for intramuscularly administered antipsychotic drugs (32).

Benzodiazepine monotherapy by the oral route can also be discussed with the patient as an option for the emergency treatment of psychomotor agitation, as long as there is no contraindication, such as alcohol intoxication. Lorazepam is available either as a film-coated tablet or as a dissolving tablet. Diazepam is unsuitable for the emergency setting because of its long half-life. Midazolam in liquid solution is not approved for psychiatric indications.

Loxapine inhalation

Loxapine is the only antipsychotic drug available in a formulation for inhalation, and it is approved only for the treatment of mild to moderate agitation. In approval studies, it was found superior to placebo with respect to the reduction of agitation in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (NNT = 3, 95% CI [2; 4]) (8). Hardly any data are available on its safety in patients suffering from intoxication; in a case series with 12 patients that appeared too late to be considered for the aforementioned clinical practice guideline, the only adverse effect mentioned for this population was mild confusion (33). Loxapine is, however, still contraindicated for patients with airway diseases, because of the risk of bronchospasm. In view of the restricted approval status of this drug and its high cost, it is likely to be used only under rare and exceptional circumstances.

Discussion

Clinical trials have shown that antipsychotic drugs and benzodiazepines are effective in the treatment of aggressive psychomotor agitation, but only two drugs have actually been approved for the treatment of aggressiveness, namely, risperidone and zuclopenthixol for aggressive behavior in the setting of Alzheimer disease or cognitive impairment of other etiology. When drugs are studied in clinical trials, patients must consent to participation, and they are then randomly allotted to one of two or more treatment groups. For both practical and ethical reasons, such a procedure is not possible when the endpoint of the study would itself affect the personal safety of the patient and others (e.g., violent attacks). As a result, agitated patients are often included in approval studies, but patients who pose an acute danger to themselves or others never are.

Intoxications are generally a reason for exclusion from clinical trials. The management of alcohol intoxication and, increasingly, of delirious states after the consumption of amphetamine-like substances (so-called bath salts or crystal meth) is a practical challenge. Available results from clinical trials are applicable only to a very limited extent (34). For patients with intoxications or manifestations of unclear origin, the current clinical practice guideline on the treatment of aggressive behavior still recommends haloperidol monotherapy on the basis of clinical experience and its good safety profile in aggressive patients with psychomotor agitation. This drug should no longer be given to non-intoxicated patients because of its low effectiveness and the adverse effects mentioned above (7).

To address the limited external validity of clinical trials, observational studies are increasingly being carried out in the routine-care setting. A Danish study in which inpatients on a psychiatric ward were observed, including patients with comorbidities and intoxications, likewise led to the conclusion that benzodiazepines and/or antipsychotic drugs are effective against aggressive psychomotor agitation, in accordance with clinical experience (35).

Conclusion

Antipsychotic drugs and benzodiazepines are effective against aggressive psychomotor agitation when given by either the parenteral or the oral route. Clinical experience shows that any of the drugs discussed in this review can have an additional, desirable placebo effect when they are administered with the acceptance of the patient, leading to the patient calming down faster than could be explained by pharmacokinetics alone. This common observation helps put the discussion of mechanisms of action, drug selection, and modes of administration in the proper context. New modes of administration and other drug classes will have their uses in exceptional situations in the future, as they already do at present.

BOX. Tips how to talk with agitated and aggressive patients.

Even when a drug must be given against the patient’s will and it is no longer possible to inform the patient at length about the treatment and then obtain his or her consent, the physician must still stay in conversation with the patient.

-

Explain roles

As a physician, I have to protect you and other people from harm, and that’s why I have to give you medication now so that you can calm down.”

-

Explain the mode of action

I am now going to give you a calming medication called X. All it does is make you feel calmer and help you take back control over your own actions. You will not go unconscious.”

-

Leave an opportunity for free choice

You are in an unusual and dangerous situation that requires medical treatment with a calming medication. Would you rather take it by mouth or as an injection?” (A patient that talks with the physician about the choice of drug is already in conversation and, therefore, less aggressive.)

-

Involve the experienced patient in the choice of medication

You have to take a medication now. Would you rather take medication X or medication Y? Which one helped you more in the past?”

-

Things to avoid

Taking action over the patient’s head: in our experience, stress situations often lead physicians to neglect talking with the patient. It is all the more important to think actively about communication in such situations.

Leaving the impression of brute force or punishment: make it clear that medical treatment is being given to protect the patient and help him or her regain self-control.

Key messages.

Medical treatment in case of aggressive behavior is indicated only when there is an underlying illness.

Before any treatment, life-threatening conditions or somatic disorders that can be readily corrected, such as hypoglycemia or an organic brain disease, must be ruled out.

Medication should be given by mouth and with the patient’s consent whenever possible.

Antipsychotic drugs and benzodiazepines are effective in the treatment of aggressive psychomotor agitation.

Haloperidol should no longer be given as monotherapy to patients who are not intoxicated.

eTable. The search strategy, according to the PICO model*1.

| Person | Intervention | Outcome |

| mental* | rapid tranquil* | violen* |

| psychiatr* | adrenergic | aggress* |

| schizo* | anticonvuls* | anger* |

| autis* | neurolept* | agitat* |

| delir* | antipsychotic* | hostil* |

| dement* | mood stabili* | aggression[MeSH Terms] |

| intellect* | benzodiazepin* | violence[MeSH Terms] |

| brain injur* | lithium | anger[MeSH Terms] |

| bipolar | psychotrop* | psychomotor agitation[MeSH Terms] |

| affective psychosis, bipolar[MeSH Terms] | adrenergic beta antagonists[MeSH Terms] | hostility[MeSH Terms] |

| behavior disorder, disruptive[MeSH Terms] | anticonvulsants[MeSH Terms] | |

| impulse control disorders[MeSH Terms] | anti dyskinesia agents[MeSH Terms] | |

| mood disorders[MeSH Terms] | central nervous system depressants[MeSH Terms] | |

| neurocognitive disorders[MeSH Terms] | psychotropic drugs[MeSH Terms] | |

| neurodevelopmental disorders[MeSH Terms] | estrogenic agents[MeSH Terms] | |

| personality disorders[MeSH Terms] | gestagenic agents[MeSH Terms] | |

| paranoid disorders[MeSH Terms] | antiandrogens[MeSH Terms] | |

| psychotic disorders[MeSH Term] | neurotransmitter agents[MeSH Terms] | |

| schizophrenia[MeSH Term] | ||

| post-traumatic stress disorder[MeSH Terms] |

*1 PICO: P = population or patient, I = intervention, C = comparison or control, O = outcome

The search terms within each column were connected with “OR”, and the columns were connected to each other with “AND”.

Column C was not incorporated into the searching strategy, as its elements largely overlapped with those of column I: thus, drugs were generally compared with other drugs.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Rita Göbel (RG) for her help with literature selection.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Pajonk FG, Schmitt P, Biedler A, et al. Psychiatric emergencies in prehospital emergency medical systems: a prospective comparison of two urban settings. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ketelsen R, Schulz M, Driessen M. Zwangsmaßnahmen im Vergleich an sechs psychiatrischen Abteilungen. Gesundheitswesen. 2011;73:105–111. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1246181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ketelsen R, Zechert C, Driessen M, Schulz M. Characteristics of aggression in the psychiatric hospital and predictors of patients at risk. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2007;14:92–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scaggs TR, Glass DM, Hutchcraft MG, Weir WB. Prehospital ketamine is a safe and effective treatment for excited delirium in a community hospital based EMS system. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2016;31:563–569. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X16000662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho JD, Dawes DM, Nelson RS, et al. Acidosis and catecholamine evaluation following simulated law enforcement „use of force“ encounters. Acad Emerg Med. 20101;7:e60–e68. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calver L, Drinkwater V, Isbister GK. A prospective study of high dose sedation for rapid tranquilisation of acute behavioural disturbance in an acute mental health unit. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde e. V. (DGPPN) Verhinderung von Zwang: Prävention und Therapie aggressiven Verhaltens bei Erwachsenen. S3-Leitlinie 2018. AWMF-Registernummer 038-022 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berardis D, Fornaro M, Orsolini L, et al. The role of inhaled loxapine in the reatment of acute agitation in patients with psychiatric disorders: a clinical review. Int J Mol Cell Med. 2017;18 doi: 10.3390/ijms18020349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cester-Martinez A, Cortes-Ramas JA, Borraz-Clares D, Pellicer-Gayarre M. New medical approach to out-of-hospital treatment of psychomotor agitation in psychiatric patients: a report of 14 cases. Emergencias. 2017;29:182–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linder LM, Ross CA, Weant KA. Ketamine for the acute management of excited delirium and agitation in the prehospital setting. Pharmacotherapy. 2018;38:139–151. doi: 10.1002/phar.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huf G, Alexander J, Gandhi P, Allen MH. Haloperidol plus promethazine for psychosis-induced aggression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005146.pub3. CD005146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ostinelli EG, Jajawi S, Spyridi S, Sayal K, Jayaram MB. Aripiprazole (intramuscular) for psychosis-induced aggression or agitation (rapid tranquillisation) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008074.pub2. CD008074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belgamwar RB, Fenton M. Olanzapine IM or velotab for acutely disturbed/agitated people with suspected serious mental illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003729.pub2. CD003729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ostinelli EG, Brooke-Powney MJ, Li X, Adams CE. Haloperidol for psychosis-induced aggression or agitation (rapid tranquillisation) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009377.pub3. CD009377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jayakody K, Gibson RC, Kumar A, Gunadasa S. Zuclopenthixol acetate for acute schizophrenia and similar serious mental illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000525.pub3. CD000525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaman H, Sampson SJ, Beck ALS, et al. Benzodiazepines for psychosis-induced aggression or agitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003079.pub4. CD003079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldacara L, Sanches M, Cordeiro DC, Jackoswski AP. Rapid tranquilization for agitated patients in emergency psychiatric rooms: a randomized trial of olanzapine, ziprasidone, haloperidol plus promethazine, haloperidol plus midazolam and haloperidol alone. Braz J Psychiatry. 2011;33:30–39. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462011000100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Citrome L. Comparison of intramuscular ziprasidone, olanzapine, or aripiprazole for agitation: a quantitative review of efficacy and safety. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1876–1885. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1209–1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kittipeerachon M, Chaichan W. Intramuscular olanzapine versus intramuscular aripiprazole for the treatment of agitation in patients with schizophrenia: a pragmatic double-blind randomized trial. Schizophr Res. 176:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kishi T, Matsunaga S, Iwata N. Intramuscular olanzapine for agitated patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;68:198–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marder SR, Sorsaburu S, Dunayevich E. Case reports of postmarketing adverse event experiences with olanzapine intramuscular treatment in patients with agitation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:433–441. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04411gry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson MP, MacDonald K, Vilke GM, Feifel D. A comparison of the safety of olanzapine and haloperidol in combination with benzodiazepines in emergency department patients with acute agitation. J Emerg Med. 2012;43:790–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen MH, Currier GW. Use of restraints and pharmacotherapy in academic psychiatric emergency services. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2004 26:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albrecht B, Staiger PK, Hall K, Miller P, Best D, Lubman DI. Benzodiazepine use and aggressive behaviour: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48:1096–1014. doi: 10.1177/0004867414548902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bieniek SA, Ownby RL, Penalver A, Dominguez RA. A double-blind study of lorazepam versus the combination of haloperidol and lorazepam in managing agitation. Pharmacotherapy. 1998;18:57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O‘Connor L, Rebesco M, Robinson C, et al. Outcomes of prehospital chemical sedation with ketamine versus haloperidol and benzodiazepine or physical restraint only. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018:1–9. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2018.1501445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Currier GW, Chou JCY, Feifel D, et al. Acute treatment of psychotic agitation: a randomized comparison of oral treatment with risperidone and lorazepam versus intramuscular treatment with haloperidol and lorazepam. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:386–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsu WY, Huang SS, Lee BS, Chiu NY. Comparison of intramuscular olanzapine, orally disintegrating olanzapine tablets, oral risperidone solution, and intramuscular haloperidol in the management of acute agitation in an acute care psychiatric ward in Taiwan. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30:230–234. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181db8715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walther S, Moggi F, Horn H, et al. Rapid tranquilization of severely agitated patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a naturalistic, rater-blinded, randomized, controlled study with oral haloperidol, risperidone, and olanzapine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;34:124–128. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mullinax S, Shokraneh F, Wilson MP, Adams CE. Oral medication for agitation of psychiatric origin: a scoping review of randomized controlled trials. J Emerg Med. 2017;53:524–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pratts M, Citrome L, Grant W, Leso L, Opler LA. A single-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sublingual asenapine for acute agitation. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130:61–68. doi: 10.1111/acps.12262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roncero C, Ros-Cucurull E, Palma-Alvarez RF, et al. Inhaled loxapine for agitation in intoxicated patients: a case series. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2017;40:281–285. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0000000000000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinert T, Hamann K. External validity of studies on aggressive behavior in patients with schizophrenia: systematic review. CP & EMH; 2012;8:74–80. doi: 10.2174/1745017901208010074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bauer JO, Stenborg D, Lodahl T, Monsted MM. Treatment of agitation in the acute psychiatric setting An observational study of the effectiveness of intramuscular psychotropic medication. Nord J Psychiatry. 2016;70:599–605. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2016.1188982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.neuraxpharm Arzneimittel GmbH. Fachinformation für Haloperidol-neuraxpharm Injektionslösung. Stand: Januar 2018. Langenfeld: neuraxpharm Arzneimittel GmbH. Zulassungsnummer 7819.00.02. www.fachinfo.de/suche/fi/021365 (last accessed on 17 March 2019) [Google Scholar]

- E2.Lilly Deutschland. Fachinformation für ZYPREXA 10 mg Pulver. Stand: November 2018. Bad Homburg: Lilly Deutschland GmbH. EU/1/96/022/016. www.fachinfo.de/suche/fi/004447 (last accessed on 17 March 2019) [Google Scholar]

- E3.Pfizer Pharma PFE GmbH. Fachinformation für ZELDOX 20 mg/ml, Pulver und Lösungsmittel zur Herstellung einer Injektionslösung. Stand: November 2016. Berlin: PFIZER PHARMA PFE GmbH. Zulassungsnummer: 53092.00.00. www.fachinfo.de/suche/fi/005810 (last accessed on 16 May 2019) [Google Scholar]