Abstract

Context:

Metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD) is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder characterized by demyelination of central and peripheral nervous system. There is scarcity of literature on the electrophysiological aspects of peripheral nerves and the advanced neuroimaging findings in MLD.

Aim:

The aim was to study the nerve conduction parameters and advanced neuroimaging findings in patients with MLD.

Materials and Methods:

This study is a retrospective analysis conducted, between 2005 and 2016, of 12 patients who had biochemical, histopathological, or genetic confirmation of MLD and disease onset before 18 years of age. The clinical, electroneurography, and the advanced neuroimaging findings were reviewed and analyzed.

Statistical Analysis:

The data were presented as percentages or mean ± standard deviation as defined appropriate for qualitative and quantitative variables.

Results:

Mean age of onset was 4.84 (±4.60) years and seven patients were males. Eight patients had juvenile MLD and four had late infantile MLD. Clinical presentation of psychomotor regression was more common in infantile MLD (75%), whereas gait difficulty (62.5%) and cognitive impairment (37.5%) were more frequent in juvenile MLD. Nerve conduction study (NCS) revealed diffuse demyelinating sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy in 9 (75%) patients. One patient had a rare presentation with conduction blocks in multiple nerves with contrast enhancement of cauda equina. Diffusion restriction involving periventricular and central white matter was seen in five patients and bilateral globus pallidi blooming was noted in three patients.

Conclusion:

This study highlights the utility of NCS and advanced magnetic resonance imaging sequences in the diagnosis of MLD.

Keywords: Advanced neuroimaging, conduction block, demyelinating neuropathy, metachromatic leukodystrophy

Key messages: • Electroneurography can be a useful adjunct tool for the detection of demyelinating neuropathy in a case of suspected metachromatic leukodystrophy., • Conduction block and cauda equina enhancement are rare findings in metachromatic leukodystrophy mimicking acquired demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathies., • Diffusion restriction involving periventricular and central white matter and bilateral globus pallidi mineralization can be seen in metachromatic leukodystrophy.

Introduction

Metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD) is a rare autosomal-recessive metabolic disorder caused by deficiency of aryl sulfatase A (ASA) enzyme.[1] ASA enzyme catalyzes 3-sulfo-galactosyl ceramide, and its deficiency leads to sulfatide accumulation in the central and peripheral nervous system.[2] Abnormal sulfatide accumulation leads to demyelination and progressive neurological deterioration.[3] Depending on the age of onset and clinical features, MLD is classified into late infantile, juvenile, and adult forms.[4] Diagnosis of MLD rests on the detection of characteristic biochemical abnormalities and genetic mutation.[5,6] The classic brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in MLD encompasses bilateral symmetric T2-weighted hyperintensities of the periventricular white matter with a tigroid pattern and sparing of the subcortical “U” fibers.[7] A similar pathology is reflected in the peripheral nervous system, which characteristically shows a demyelinating peripheral neuropathy.[8]

There is scarce literature on the utility of nerve conduction studies (NCSs) and advanced neuroimaging techniques such as diffusion-weighted images (DWI) and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) in the diagnosis of MLD.[9] We aimed to study the electroneurographic and neuroimaging profile of patients with MLD in our center.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patients diagnosed with MLD, admitted to the Department of Neurology from 2005 to 2016 in our Institute. The ethical and methodological aspects of this study were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. The study sample was identified via reviewing computer-based hospital records of all patients admitted with diagnosis of leukodystrophy.

Patients with clinical and MRI features suggestive of MLD were included in the study if they satisfied any one of the following three criteria: (1) low ASA enzyme levels in leucocytes, (2) homozygous pathogenic mutation in ASA gene, and (3) presence of metachromatic granules in nerve biopsy or urine. Patients with age of onset more than 18 years and those whose electroneurography data were unavailable were excluded from the study. The clinical and NCS parameters of these patients were retrospectively reviewed from systematically maintained case records. The patients with MLD were subclassified into infantile (0–4 years) and juvenile form (4–16 years) based on the age of onset of symptoms and their clinical characteristics.[2] The gross motor function was scored based on Gross Motor Function Classification for MLD (GMFC-MLD). It is a seven-point scoring system from level 0–6, and level 6 corresponds to loss of any locomotion including loss of head control.[10]

The nerve conduction parameters of all patients were reviewed by an electrophysiologist. A single motor and sensory nerve in one lower and upper limbs were included for the analysis of NCS. For consistency, we selected median nerve in the upper limb and tibial and sural nerves in the lower limbs for the electrophysiological analysis. Demyelinating neuropathy was defined based on the criteria for hereditary neuropathy as median motor conduction velocity less than 38 m/s.[11,12]

MRI brain in the picture archiving and communication system (PACS) was reviewed by a neuroradiologist. The brain MRI scoring system for MLD (MRI-MLD) was carried out in T2-weighted and fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) axial sequence. MRI-MLD scoring is a 34-point scoring based on the site and extent of the white matter involvement and atrophy with higher scores, indicating more extensive white matter involvement.[13] DWI, susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) sequences, and MRS findings were also noted.

Statistical Analysis

The data were presented as percentages or mean ± standard deviation as defined appropriate for qualitative and quantitative variables. The clinical and electrophysiological parameters were compared between the infantile and juvenile forms of MLD.

Results

The records of 66 patients admitted with diagnosis of leukodystrophy between 2000 and 2015, were screened, of whom 12 patients satisfying the inclusion criteria were included in this analysis. Mean age of onset was 4.84 (±4.60) years and seven patients were males. Eight patients were classified as juvenile MLD and four as late infantile MLD. The clinical features and MRI findings are described in Table 1. One patient (P-11) had a very rare presentation of MLD, which is described in detail.

Table 1.

Clinical and investigation parameters in MLD

| Clinical parameter | Total (n = 12) | Infantile MLD (n = 4) | Juvenile MLD (n = 8) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of onset in years, mean ± SD | 4.84 ± 4.60 | 0.65 ± 0.58 | 6.91 ± 4.31 |

| Males | 7 (58.3) | 1 (25) | 6 (75) |

| Motor impairment | 10 (83.3) | 4 (100) | 6 (75) |

| Neurocognitive impairment | 11 (91.7) | 4 (100) | 7 (87.5) |

| Psychomotor regression | 3 (25) | 3 (75) | 0 (0) |

| Language impairment | 11 (91.7) | 4 (100) | 7 (87.5) |

| Seizures | 2 (16.7) | 1 (25) | 1 (12.5) |

| Startle myoclonus | 1 (8.3) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Cerebellar ataxia | 3 (25) | 1 (25) | 2 (25) |

| Extrapyramidal | 3 (25) | 0 (0) | 3 (37.5) |

| Optic atrophy | 3 (25) | 2 (50) | 1 (12.5) |

| Positive family history | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (25) |

| Consanguinity | 5 (41.7) | 0 (0) | 5 (62.5) |

| Demyelinating peripheral neuropathy | 9 (75) | 3 (75) | 6 (75) |

| MRI-MLD score, mean ± SD* | 19.75 ± 5.95 | 16.5 ± 6.36 | 20.83 ± 5.98 |

| GMFC-MLD, median (range) | 2 (1–6) | 6 (2–6) | 2 (1–6) |

Number in the parenthesis = percentage, SD = standard deviation

*MRI scoring was carried out only in two and six patients with infantile MLD and juvenile MLD, respectively

Infantile MLD: Mean age of onset was 0.65 ± 0.58 years among four patients (P-5, 6, 7, and 10) with late infantile MLD. Psychomotor regression was the most common presentation in all except one patient. None had consanguineous parentage or family history of MLD. All of them had bilateral spasticity and two had areflexia. The median GMFC-MLD was 6, suggestive of severe impairment.

Juvenile MLD: Mean age of onset for juvenile MLD was 6.91 ± 4.31 years and six were males. Gait difficulty and cognitive impairment were the most common presentations seen in five and three patients, respectively. All patients had pyramidal involvement with areflexia in five. Extrapyramidal features (generalized dystonia) were seen in three patients and ataxia in two patients. Consanguinity was noted in five patients, and positive family history of MLD in two patients in whom genetic confirmation was available. EEG was available only for four patients, which revealed background slowing in two patients and epileptiform discharges in one patient. Three patients who underwent lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed elevated proteins with no cells suggestive of albumino-cytological dissociation.

Electrophysiology: NCS parameters were available in upper and lower limbs of all patients except in P-7 (only lower limb conduction was available). NCS parameters of each patient is described in detail in Table 2. In the infantile form except in P-10, NCS revealed diffuse demyelinating sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy. Conduction velocities were diffusely reduced in the range of 19–21 m/s in median nerve and 15–20 m/s in tibial nerve. In juvenile MLD, NCS revealed diffuse demyelinating sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy in six patients. Conduction velocities were diffusely slowed, in the range of 13–27 m/s in median nerve and 13–31 m/s in tibial nerve. Conduction blocks in multiple nerves were noted in a single patient (P-11) with juvenile MLD.

Table 2.

NCS parameters in patients with MLD

| Cases | Age*, y | Median nerve motor conduction |

Tibial nerve motor conduction |

Median nerve sensory conduction | Sural nerve sensory conduction | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL (ms) | Amp (mV) | CV (m/s) | F (ms) | CB | DL (ms) | Amp (mV) | CV (m/s) | F (ms) | CB | PL (ms) | Amp (µV) | PL (ms) | Amp (µV) | ||

| P-1 | 5.3 | 8.8 | 4 | 18 | 67.8 | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | 2.2 | 3 |

| P-2 | 24 | 7.3 | 9.3 | 24 | 68.5 | A | 6.9 | 6.3 | 13 | A | A | A | A | A | 0 |

| P-3 | 5.6 | 4.8 | 6.2 | 27 | A | A | 5.1 | 7.4 | 31 | 52.1 | A | 4.2 | 20 | 5.7 | 5 |

| P-4 | 8.7 | 2.2 | 17.6 | 63 | 16.7 | A | 2.4 | 31.7 | 52 | 30.1 | A | 2.4 | 88 | 2.5 | 31 |

| P-5 | 0.8 | 4.7 | 3.1 | 21 | A | A | 4.6 | 1.1 | 15 | A | A | A | A | A | A |

| P-6 | 2.2 | 4.7 | 2.3 | 19 | 38.9 | A | 5.5 | 1.1 | 20 | A | A | A | A | A | A |

| P-7 | 4 | ND | ND | ND | ND | A | 9.7 | 2.3 | 17 | A | A | ND | ND | A | A |

| P-8 | 20 | 3.2 | 9.4 | 60 | 26.5 | A | 4 | 9 | 45 | 52.7 | A | 3 | 49.5 | 3.4 | 13.5 |

| P-9 | 17 | 7.9 | 10.9 | 24 | 67.4 | A | A | A | A | A | A | 6.7 | 12.2 | A | A |

| P-10 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 5.9 | 53 | 21.5 | A | 3.1 | 22.3 | 48 | 27.3 | A | 2 | 41.2 | 2.9 | 22.3 |

| P-11 | 8.8 | 9.6 | 1.7 | 13 | A | P | A | A | A | A | A | 3.5 | 13 | 3.3 | 4 |

| P-12 | 3 | 5.6 | 7.4 | 16 | 45 | A | 6.9 | 5.8 | 13 | 67.9 | A | 4.8 | 5.9 | 3.2 | 3.3 |

A = absent, Amp = amplitude, CB = conduction block, CV = conduction velocity, DL = distal latency, F = F wave latency, ms = milliseconds, ND = not done, P = patient, PL = peak latency, y = years

*Age at which nerve conduction study was performed

MRI: Only eight MR images were available for review in PACS (two cases of late infantile and six cases of juvenile MLD). The mean MRI-MLD score was 19.75 (±5.95). Conventional T2-weighted sequences showed typical white matter dense hyperintensities involving periventricular and central regions of frontal, parieto-occipital, and temporal region in all patients. Hyperintensities were also noted in the subcortical U fibers of frontal and parieto-occipital region in four and six patients, respectively. Subcortical U fiber involvement of temporal lobe was rarely noted, it was seen in one patient only. Callosal involvement was seen in all with splenium and genu involvement in seven and four patients, respectively. Posterior limb of internal capsule was commonly involved (six patients), whereas anterior limb of internal capsule was rarely involved (one patient).

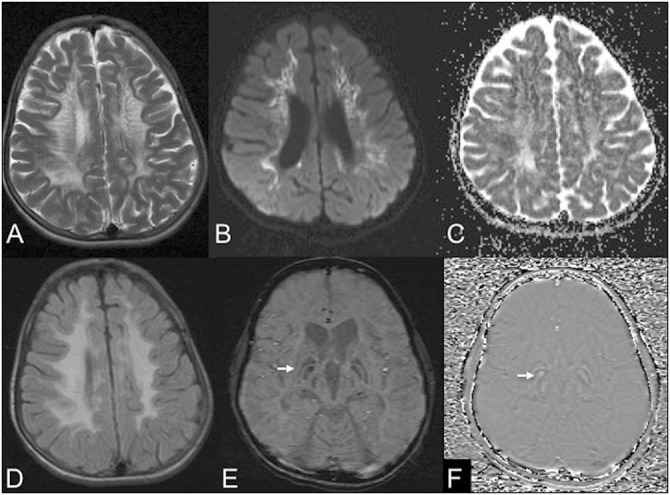

DWI (seven patients) showed diffusion restriction involving periventricular and central white matter in five patients with one of them showing cerebellar white matter restriction. MRS was available for four patients, which showed lactate peak in all with decreased N-acetylaspartate (NAA)/Creatine peak in three. SWI (six patients) showed bilateral globus pallidi (GPi) blooming in three patients [Figure 1]. These three patients, which showed GPi blooming, had generalized dystonia.

Figure 1.

MRI of a 17-year-old boy with neuropsychiatric manifestations and dystonia. Axial images T2W (A) and FLAIR (D) show confluent periventricular white matter hyperintensities with a classical tigroid appearance in T2. DWI (B) and apparent diffusion coefficient (C) show diffusion restriction in affected white matter. SWI (E) shows prominent susceptibility (arrows) involving the GPi bilaterally with positive phase shift on phase images (F) consistent with exaggerated mineralization

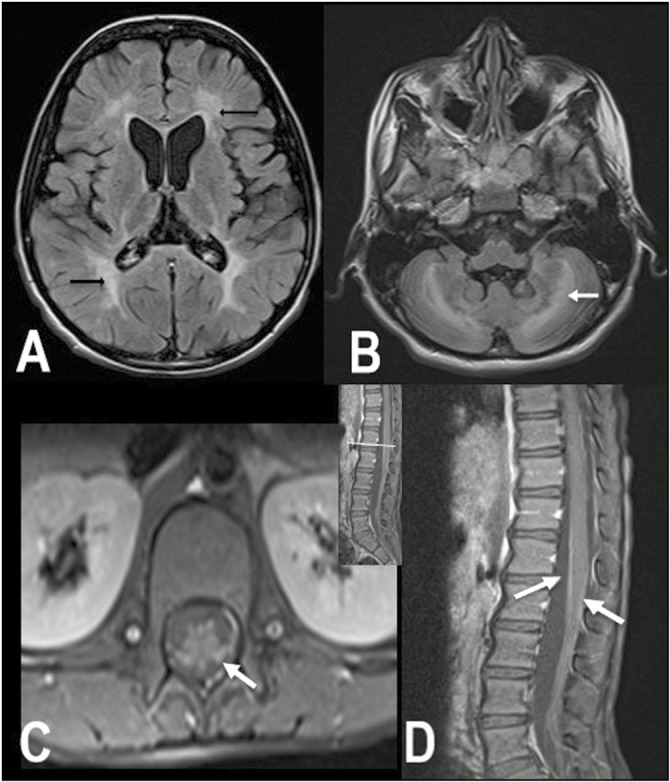

Rare presentation of MLD: P-11 presented with progressive gait difficulty and cognitive impairment since 5 years of age and reached GMFC-MLD level 6 within 2 years of onset. His CSF revealed albumino-cytologic dissociation. NCS was suggestive of demyelinating neuropathy and had evidence of conduction block in multiple nerves. His MRI brain was specific for MLD but showed contrast enhancement of the lumbosacral roots and cauda equina [Figure 2]. He was given a trial of corticosteroids in view of these atypical findings while awaiting biopsy report. However, he showed no clinical improvement. His nerve biopsy showed severe loss of myelinated fibers and accumulation of metachromatic granules on cresyl violet staining.

Figure 2.

MRI brain and spine images of P-11. Axial FLAIR shows bilateral confluent symmetric periventricular and deep white matter hyperintensities (arrows) in both the cerebrum (A) and cerebellum (B). Contrast-enhanced fat saturated T1 axial (C) and sagittal (D) images of the lumbar spine show smooth enhancement of the cauda equina nerve roots (arrows)

Discussion

In this study, we have described the clinical features, MRI abnormalities, and nerve conduction parameters in four infantile and eight juvenile patients with MLD. A demyelinating sensorimotor neuropathy was recorded in 75% of the cases with one showing conduction block. Bilateral GPi blooming was noted in three patients with extrapyramidal manifestations.

Majority of our cases had clinical evidence of neuropathy in the form of areflexia, which corroborated with the NCS. Demyelinating neuropathy in MLD observed in our study was also reported earlier; however, the exact incidence is not known.[14] One of our patients had conduction block and enhancement of cauda equina, which could suggest an acquired demyelinating neuropathy. However, the presence of multifocal slowing, abnormal temporal dispersion, and partial or complete conduction blocks are not absolute for acquired neuropathies and have also been described in Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease, MLD, adrenoleukodystrophy, and Krabbe disease.[14] In these scenarios, contrast enhancement of cauda equina in MRI and albumino-cytologic dissociation in CSF in a given patient can point to a diagnosis of acquired demyelinating neuropathy, especially when MRI brain is normal. Clinical evolution of disease and subsequent MRI brain should settle the diagnosis.[15] The enhancement of cranial nerves has also been rarely reported previously, in addition to involvement of cauda equina in infantile MLD and Krabbe disease. The abnormal excessive accumulation of sulfatide in the peripheral nerves with resultant breakdown of blood–nerve barrier is a possible explanation for the contrast enhancement in MLD.[16] Similarly, sulfatide accumulation in the paranodal region in a segmental pattern might explain the conduction block, though the exact mechanism is unknown.[14] Hence, the diagnosis of MLD should be considered in a patient with demyelinating peripheral neuropathy and cerebral manifestations.

Imaging characteristics were consistent with previously described studies with predominant involvement of periventricular white matter and sparing of temporal subcortical U fibers.[13] A key feature of the study was the findings observed in advanced imaging modalities in our patients. DWI images in our juvenile patients with MLD showed restricted diffusion in periventricular white matter. This could be due to the cytotoxic or myelin edema; a result of sulfatide accumulation before myelin breakdown.[9] MRS in four of our patients revealed reduced NAA levels along with elevated lactate levels. Reduced NAA to creatine with elevated lactate is consistent with axonal damage and gliosis secondary to demyelination. Similar findings are also noted in other leukodystrophies and are not specific to MLD.[17] Another unique finding observed in our study was the presence of SWI blooming in GPi in three patients with generalized dystonia. To the best of our knowledge, no previous results have been published on SWI characteristics in MLD. However, mineralization of Gpi has been reported in neuronal brain iron accumulation and type III GM1 gangliosidosis.[18] The reason for basal ganglia mineralization in MLD and other metabolic disorder is obscure and requires further studies.

Various limitations are notable in our study, first, being a relatively small sample size, and second, the absence of a genetic confirmation in all the cases. Considering the rarity of disease, our study highlights the importance of NCS in MLD and gives a bird’s-eye view of advanced imaging features in MLD. We also presented a rare manifestation of MLD, which can be easily mistaken for an acquired demyelinating neuropathy. Moreover, the presence of Gpi mineralization in patients with MLD who presented with dystonia is a new finding not yet described.

Conclusion

In the evaluation of leukodystrophy, electroneurography can aid in the detection of peripheral demyelination, thus narrowing the diagnostic possibilities. The presence of conduction block and cauda equina enhancement mimicking an acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy can be a rare presentation in MLD. Advanced neuroimaging reveals diffusion restriction involving periventricular and central white matter and bilateral GPi mineralization in MLD.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Deconinck N, Messaaoui A, Ziereisen F, Kadhim H, Sznajer Y, Pelc K, et al. Metachromatic leukodystrophy without arylsulfatase A deficiency: a new case of saposin-B deficiency. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2008;12:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gieselmann V. Metachromatic leukodystrophy: recent research developments. J Child Neurol. 2003;18:591–4. doi: 10.1177/08830738030180090301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Webster HD. Schwann cell alterations in metachromatic leukodystrophy: preliminary phase and electron microscopic observations. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1962;21:534–54. doi: 10.1097/00005072-196210000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biffi A, Lucchini G, Rovelli A, Sessa M. Metachromatic leukodystrophy: an overview of current and prospective treatments. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42:S2–6. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Artigalás O, Lagranha VL, Saraiva-Pereira ML, Burin MG, Lourenço CM, van der Linden H, Jr, et al. Clinical and biochemical study of 29 Brazilian patients with metachromatic leukodystrophy. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010;33:S257–62. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacFaul R, Cavanagh N, Lake BD, Stephens R, Whitfield AE. Metachromatic leucodystrophy: review of 38 cases. Arch Dis Child. 1982;57:168–75. doi: 10.1136/adc.57.3.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang E, Prabhu SP. Imaging manifestations of the leukodystrophies, inherited disorders of white matter. Radiol Clin North Am. 2014;52:279–319. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bindu PS, Mahadevan A, Taly AB, Christopher R, Gayathri N, Shankar SK. Peripheral neuropathy in metachromatic leucodystrophy. A study of 40 cases from south India. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1698–701. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.063776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oguz KK, Anlar B, Senbil N, Cila A. Diffusion-weighted imaging findings in juvenile metachromatic leukodystrophy. Neuropediatrics. 2004;35:279–82. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-821301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kehrer C, Blumenstock G, Raabe C, Krägeloh-Mann I. Development and reliability of a classification system for gross motor function in children with metachromatic leucodystrophy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53:156–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harding AE, Thomas PK. The clinical features of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy types I and II. Brain. 1980;103:259–80. doi: 10.1093/brain/103.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller RG, Gutmann L, Lewis RA, Sumner AJ. Acquired versus familial demyelinative neuropathies in children. Muscle Nerve. 1985;8:205–10. doi: 10.1002/mus.880080305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eichler F, Grodd W, Grant E, Sessa M, Biffi A, Bley A, et al. Metachromatic leukodystrophy: a scoring system for brain MR imaging observations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:1893–7. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cameron CL, Kang PB, Burns TM, Darras BT, Jones HR., Jr Multifocal slowing of nerve conduction in metachromatic leukodystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2004;29:531–6. doi: 10.1002/mus.10569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haberlandt E, Scholl-Bürgi S, Neuberger J, Felber S, Gotwald T, Sauter R, et al. Peripheral neuropathy as the sole initial finding in three children with infantile metachromatic leukodystrophy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2009;13:257–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morana G, Biancheri R, Dirocco M, Filocamo M, Marazzi MG, Pessagno A, et al. Enhancing cranial nerves and cauda equina: an emerging magnetic resonance imaging pattern in metachromatic leukodystrophy and Krabbe disease. Neuropediatrics. 2009;40:291–4. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Assadi M, Wang DJ, Velazquez-Rodriquez Y, Leone P. Multi-voxel 1H-MRS in metachromatic leukodystrophy. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 2013;5:25–30. doi: 10.4137/JCNSD.S11861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pillai SH, Sundaram S, Zafer SM, Rajan R. Expanding the phenotypic spectrum of type III GM1 gangliosidosis: progressive dystonia with auditory startle. Neurol India. 2018;66:149–50. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.226465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]