Abstract

Introduction

We aimed to identify whether acute ischemic stroke patients with known complete reperfusion after thrombectomy had the same baseline computed tomography perfusion (CTP) ischemic core threshold to predict infarction as thrombolysis patients with complete reperfusion.

Methods

Patients who underwent thrombectomy were matched by age, clinical severity, occlusion location, and baseline perfusion lesion volume to patients who were treated with intravenous alteplase alone from the International Stroke Perfusion Imaging Registry. A pixel‐based analysis of coregistered pretreatment CTP and 24‐hour diffusion‐weighted imaging (DWI) was then undertaken to define the optimum CTP thresholds for the ischemic core.

Results

There were 132 eligible thrombectomy patients and 132 matched controls treated with alteplase alone. Baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (median, 15; interquartile range [IQR], 11–19), age (median, 65; IQR, 59–80), and time to intravenous treatment (median, 153 minutes; IQR, 82–315) were well matched (all p > 0.05). Despite similar baseline CTP ischemic core volumes using the previously validated measure (relative cerebral blood flow [rCBF], <30%), thrombectomy patients had a smaller median 24‐hour infarct core of 17.3ml (IQR, 11.3–32.8) versus 24.3ml (IQR, 16.7–42.2; p = 0.011) in alteplase‐treated controls. As a result, the optimal threshold to define the ischemic core in thrombectomy patients was rCBF <20% (area under the curve [AUC], 0.89; 95% CI, 0.84, 0.94), whereas in alteplase controls the optimal ischemic core threshold remained rCBF <30% (AUC, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.77, 0.85).

Interpretation

Thrombectomy salvaged tissue with lower CBF, likely attributed to earlier reperfusion. For patients who achieve rapid reperfusion, a stricter rCBF threshold to estimate the ischemic core should be considered. Ann Neurol 2017;82:995–1003

The central premise of acute ischemic stroke treatment is to limit infarction with rapid and effective recanalization of an occluded blood vessel, thereby reperfusing ischemic penumbra surrounding the irreversibly injured ischemic core.1 A number of studies have estimated the baseline ischemic core volume using computed tomography (CT) perfusion (CTP), finding that cerebral blood flow (CBF) <30% (compared to normal tissue) is a robust and reliable threshold for ischemic core prediction.2, 3, 4 However, these studies were performed in patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis or no therapy, where the time of recanalization was uncertain and likely delayed in many cases. Even studies that have compared baseline CTP with acute diffusion‐weighted imaging (DWI) leave a time delay between imaging acquisitions.5 In patients with penumbra, this might allow the ischemic core to expand between the two imaging time points and lead to an overestimation of the true ischemic core at the time of baseline CTP. Recent evidence indicates that thrombectomy results in more rapid and complete recanalization than does intravenous thrombolysis alone.6 Indeed, it has been suggested that early reperfusion after thrombectomy leads to the pretreatment CTP ischemic core (albeit measured with cerebral blood volume [CBV]) overestimating final infarct volume.7 In the setting of early and complete reperfusion, regardless of treatment modality (and perhaps even following spontaneous reperfusion), the previously validated thresholds for ischemic core on CTP may not apply. Therefore, we hypothesized that patients with known early and complete revascularization were more likely to salvage tissue that is severely hypoperfused and might typically be considered ischemic core.8, 9 To test this hypothesis, we sought to determine whether a cohort of patients with known time of revascularization following thrombectomy had similar optimal baseline CTP ischemic core thresholds compared to patients with complete reperfusion treated with intravenous thrombolysis (in whom the time of revascularization was less certain).

Patients and Methods

Consecutive acute ischemic stroke patients presenting to the hospital within 4.5 hours of symptom onset at three centers ([1] John Hunter Hospital, [2] Royal Adelaide Hospital, and [3] the University of Alberta Hospital, Canada) between 2012 and 2016 were prospectively recruited for the International Stroke Perfusion Imaging Registry (INSPIRE). INSPIRE is a registry of multimodal imaging with a focus on perfusion from acute ischemic stroke cases, regardless of the therapy received. All patients underwent baseline multimodal computed tomography (CT) imaging (noncontrast CT [NCCT], CT angiography [CTA], and CTP) and follow‐up magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (MRI) at 24 hours poststroke. Clinical stroke severity was assessed at the two imaging time points using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS). Eligible patients were treated with intravenous thrombolysis and those with a large vessel occlusion underwent thrombectomy, where appropriate, according to local guidelines and the clinical judgement of the treating physician and neurointerventionalist. The modified Rankin scale (mRS) was assessed at 90 days poststroke. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the INSPIRE protocol was approved by the local ethics committees in accordance with Australian National Health and Medical Research Council guidelines.

Acute Multimodal CT Protocol

Acute CT imaging included brain NCCT, CTP, and extracranial CTA using either 128, 256, or 320 detector scanners (Siemens Somatom Definition (Siemens Healthcare, Forchheim, Germany) and Toshiba Aquilion One (Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation, Tochigi‐ken, Japan)) . Axial slice coverage ranged from 41 to 160 mm. CTA was performed after perfusion CT with acquisition from the aortic arch to vertex.10 Scanner details are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Patients selected for thrombectomy had digital subtraction imaging before and immediately after therapy to confirm vessel occlusion and then revascularization.

24‐Hour Imaging Protocol

As close as possible to 24 hours after acute imaging, all patients, regardless of treatment, underwent a stroke MRI protocol on a 1.5 Tesla (T) or 3T scanner (Siemens Avanto or Verio). The MR protocol included: DWI, perfusion‐weighted imaging, MR time of flight angiography (MRA), and fluid‐attenuated inversion recovery imaging.

Imaging Assessments

Baseline vessel occlusion status was determined on CTA, and revascularization status was determined on 24‐hour MRA or CTA in the intravenous alteplase patients, and in the endovascular‐treated patients, on post‐thrombectomy digital subtraction angiography (DSA). Thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (TICI) grades were assessed by experienced reviewers (A.B. and M.P.). Only patients with a TICI score of 3 (complete revascularization) and complete reperfusion (defined as a reduction of the perfusion lesion of >90% from baseline to 24‐hour perfusion imaging, measured by delay time [DT] >3 seconds lesion) were included in this analysis.

Selection of Controls

From the INSPIRE database of over 1,000 alteplase‐treated patients, patients who underwent thrombectomy were matched 1:1 to patients who received intravenous alteplase only at the same centers based on vessel occlusion location, and then were further matched for age, acute NIHSS, and baseline perfusion lesion volumes (core and total perfusion lesion) using probabilistic matching. All selected alteplase case controls were required to show complete recanalization and reperfusion on follow‐up imaging. For the perfusion lesion volumes, each patient's baseline CTP was automatically processed using commercial software (MiStar; Apollo Medical Imaging Technology, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) to provide the volume of the baseline perfusion lesion, penumbra, and ischemic core. A previously validated thresholds was applied in order to measure the volume of the acute perfusion lesion (relative DT >3 seconds).11 Penumbral volume was calculated as the volume of the perfusion lesion (DT threshold >3 seconds) minus the volume of the ischemic core (relative CBF [rCBF] threshold <30% within the DT >3‐second lesion).

An essential criteria for alteplase‐treated controls was complete large‐vessel occlusion (internal carotid artery [ICA], M1, or M2) with complete recanalization (TICI 3) at 24 hours on follow‐up imaging. An essential inclusion criterion for the thrombectomy patients was complete recanalization (TICI 3) on post‐thrombectomy DSA. All patients also had to achieve >90% reperfusion on 24‐hour perfusion imaging.

Imaging Analysis to Determine Core Thresholds

Baseline CTP source image data were individually coregistered to the corresponding 24‐hour DWI (b = 1,000 image) anatomical location using manual initialization as well as scaling and shear transforms to correct for echoplanar imaging artefacts. Cases that failed these coregistration attempts were excluded.

Baseline perfusion imaging maps were processed centrally with commercial software (MiStar; Apollo Medical Imaging) using deconvolution analysis and delay correction. Areas of no blood flow, chronic infarction, or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) regions were masked from the perfusion maps: No blood flow pixels were removed by eliminating areas where cerebral blood flow = 0 and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)/ventricle and skull pixels were removed using a Hounsfield unit threshold and geometrical analysis. The 24‐hour DWI lesions were delineated based on signal intensity and highlighted using an area of interest tool. Regions of interest were transferred to the coregistered baseline CTP maps for volume analysis. The final ischemic core volume was measured on the 24‐hour DWI sequence. The ability of the CTP‐defined ischemic core to predict this lesion was assessing with a receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive results and quantitative baseline patients’ characteristics are presented as mean ± standard deviation, or median and interquatile range (IQR). Paired t tests or Wilcoxon's signed‐rank tests were performed for parametric data or nonparametric data.

Based on the optimal thresholds for ischemic core from past studies, we investigated a range of rCBF (0–50% of contralateral at 5% steps) and relative CBV [rCBV] (0–50% of contralateral at 5% steps) thresholds to determine the most accurate measure of the acute ischemic core.12 ROC curve analysis was used to test the predictive performance of CTP in relation to the DWI infarct core. The DWI image was considered to be the “true” lesion, and the pixels where the DWI lesion and perfusion CT lesion overlapped were considered to be “true positive.” DWI pixels not within the perfusion CT lesion were considered to be “true negative.” Pixels within the perfusion CT lesion, but not within the DWI lesion, were assigned as “false positive,” and pixels within the DWI lesion, but not within the perfusion CT lesion, were assigned as “false negative.” Specificity [true negative/(true negative + false positive)] and sensitivity [true positive/(true positive + false negative)] were calculated for each perfusion map. Results presented are area under curve (AUC; and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) for the whole ROC curve for a perfusion map at a single threshold. Specificity, sensitivity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were calculated for each threshold increment (eg, CBF or mean transit time). The optimal thresholds were determined by the AUC and the minimum volumetric difference between acute DWI and CTP.

The influence of time from stroke onset to CTP and also time from CTP to reperfusion on the optimal CTP baseline ischemic core thresholds were assessed. First, the effect of time from stroke onset to CTP on the optimal CTP threshold to define the baseline ischemic core was tested using linear regression using age and baseline NIHSS as independent variables. An interaction analysis was also undertaken to identify whether there was a relationship between time from stroke onset on the optimal CTP threshold to define the baseline ischemic core. Next, given that patients who underwent endovascular therapy had a known time of revascularization, patients who had endovascular therapy were divided into two epochs based on time from CTP to confirmed TICI 3 on DSA at <90 and >90 minutes. The previous analyses to define optimal CTP threshold for baseline ischemic core were repeated in these two time epochs.

Clinical outcomes from patients undergoing thrombectomy and intravenous thrombolysis on the mRS and NIHSS were compared using linear regression. A common odds ratio was used for the 90‐day mRS to compare each treatment group. Statistical analyses were performed with STATA software (version 13.0; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Over the study period, the INSPIRE registry collected 2,038 patients who underwent acute CTP imaging within 4.5 hours of symptom onset and received intravenous thrombolysis. There were 195 patients treated with thrombectomy and for whom complete imaging including baseline CTP, CTA, and DSA, as well as 24‐hour MRI (diffusion and perfusion) were recorded. Sixty‐three patients were excluded because of failure to achieve TICI 3 after thrombectomy (31), incomplete clinical data entry (13), severely motion‐affected imaging (3), incomplete follow‐up MRI (9), or uncertain time of stroke onset (7). The remaining 132 thrombectomy patients were 1:1 matched with alteplase‐only–treated patients from the same center based on acute NIHSS, age, occlusion location, and baseline perfusion lesion volume. All alteplase‐treated controls had to demonstrate complete recanalization and reperfusion at 24 hours.

Forty‐eight patients had an intracranial internal carotid occlusion, 102 had an M1 middle cerebral artery occlusion, and 18 had an M2 occlusion. A total of 87 of the 132 endovascular‐treated patients also received intravenous alteplase, but had persisting occlusions at the time of the procedure. There were no significant differences in baseline clinical characteristics between thrombectomy‐ or intravenous‐treated groups (Table 1). The median baseline NIHSS in the 132 thrombectomy patients was 15 (IQR, 9–22) and 13 (IQR, 6–19) in the alteplase patients (p = 0.195). The median age of the thrombectomy and alteplase patients was 65 (IQR, 59–80) and 63 (IQR, 55–79), respectively (p = 0.492). The median onset time to lysis for patients undergoing thrombectomy was 148 minutes (IQR, 95–255) whereas patients receiving intravenous lysis only was 153 minutes (IQR, 82–315; p = 0.297). The median onset to revascularization time in thrombectomy patients was 239 minutes (IQR, 109–645). For alteplase‐treated patients, the median time from treatment to follow‐up imaging was 19.3 hours (IQR, 15.1–27.6).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics Between Study Groups

| Parameter | Alteplase‐Treated Patients (n = 132) | Thrombectomy Patients (n = 132) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median, IQR) | 63 (55–79) | 65 (59–80) | 0.492 |

| Sex (male %) | 42% | 48% | 0.387 |

| Baseline NIHSS (median, IQR) | 13 (6–19) | 15 (9–22) | 0.195 |

| 24‐hour NIHSS (median, IQR) | 9 (3–13) | 6 (2–11) | 0.048 |

| Median 90 day mRS (median, range) | 3 (0–5) | 2 (0–5) | 0.027 |

| Mean baseline ischemic core (CBF 30%) | 21.7 (14.8–52.1) | 25.4 (17.3–45.8) | 0.519 |

| Mean baseline ischemic core (CBF 20%) | 14.3 (6.2–47.8) | 17.6 (11.8–41.6) | 0.139 |

| Median baseline perfusion lesion volume (DT >3 seconds) | 82 (41–297) | 87 (53–227 | 0.311 |

| Median 24‐hour DWI lesion volume (IQR) | 24.3 (16.7–42.2) | 17.3 (11.3–32.8) | 0.011 |

| Median onset to door time (IQR) | 130 (59,164) | 118 (42, 159) | 0.297 |

| Median onset to lysis time (min, IQR)a | 153 (82–315) | 148 (95–255) | 0.478 |

| Onset to revascularization time (IA patients, median, IQR) | 239 (109–645) | NA | |

| Occlusion location | |||

| M1 (%) | 82 (62%) | 82 (62%) | 1.00 |

| M2 (%) | 18 (14%) | 18 (14%) | 1.00 |

| ICA (%) | 32 (24%) | 32 (24%) | 1.00 |

| Collateral grading's | |||

| Good (%) | 40 | 48 | 0.487 |

| Moderate (%) | 27 | 24 | 0.291 |

| Poor (%) | 33 | 28 | 0.334 |

Thrombectomy patients were matched 1:1 for occlusion site, baseline perfusion lesion volume, recanalization status, and acute NIHSS. All patients in this study achieved TICI 3 or complete recanalization with treatment.

Note that not all thrombectomy patients received alteplase.

IQR = interquartile range; NIHSS = National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; mRS = modified Rankin scale; CBF = cerebral blood flow; DT = delay time; DWI = diffusion‐weighted imaging; ICA = internal carotid artery; TICI = thrombolysis in cerebral infarction.

The mean baseline ischemic core volume at a threshold rCBF <30% was 25.4ml (17.3–45.8) in the thrombectomy group and 21.7ml (14.8–52.1; p = 0.519) in the alteplase‐only group. Baseline CTP lesion volume (DT >3 seconds) was 82ml median (IQR, 41–297) in the thrombectomy group and 87ml median (IQR, 53–227) in the alteplase group (p = 0.311). Despite similar baseline CBF 30% core volumes, the median 24‐hour DWI infarct volume in thrombectomy patients was smaller (17.3ml; IQR, 11.3–32.8) than alteplase‐treated (24.3ml; IQR, 16.7–42.2; p = 0.011) patients. This was associated with lower NIHSS scores at 24 hours and mRS scores at 3 months (Table 1). Thrombectomy patients had improved 90‐day mRS scores than those treated with alteplase alone (ordinal mRS odds ratio, 1.8; p = 0.027).

Defining Ischemic Core in Patients Treated With Thrombectomy

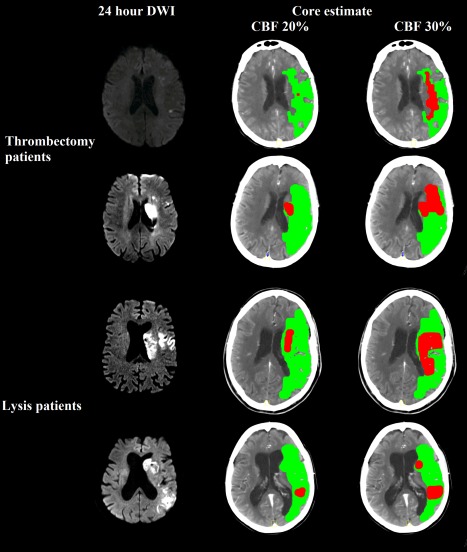

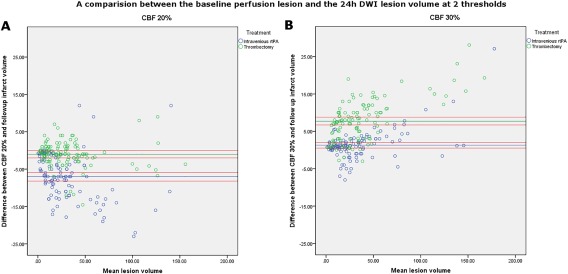

In the thrombectomy patients, the optimal ischemic core threshold was rCBF <20% (AUC, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.84, 0.94; Table 2; Figs 1 and 2). The next best threshold to define the ischemic core on baseline CTP was rCBV <30% (AUC, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.79, 0.88). rCBF <30% overestimated the 24‐hour DWI lesion (Fig 1). The rCBF<30% core volume was a median 12ml larger than the 24‐hour DWI lesion in thrombectomy patients (IQR, −1.77, −33.29ml; p = 0.019; Fig 2) whereas the rCBF <20% core was not significantly different to DWI volume (median difference, −2.6ml; IQR, −4.30, 8.78; p = 0.867). The median absolute difference in thrombectomy patients between the 24‐hour DWI infarct core volume and the CBF <30% patients was 8.3ml (IQR, 5.3–9.7) whereas for a CBF <20 the median absolute difference was 2.1ml (IQR, −1.1 to 3.7).

Table 2.

Results Showing the Optimal Thresholds to Identify the Baseline Ischemic Core in Patients Treated With Thrombectomy Compare the Alteplase Alone

| AUC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | Sensitivity | Specificity | Volume Difference | ||

| (CTP‐DWI) | |||||

| (median, IQR) (ml) | p | ||||

| Thrombectomy patients | |||||

| CBF <15% | 0.84 (0.79, 0.89) | 0.94 | 0.79 | 1.52 (–20.89, 26.79) | 0.187 |

| CBF <20% | 0.89 (0.85, 0.94) | 0.91 | 0.87 | 2.61 (–4.30, 8.78) | 0.867 |

| CBF <25% | 0.86 (0.81, 0.91) | 0.86 | 0.93 | 8.59 (–16.05, 24.51) | 0.135 |

| CBV <25% | 0.73 (0.68, 0.81) | 0.92 | 0.77 | −1.38 (–17.16, 17.31) | 0.610 |

| CBV <30% | 0.84 (0.79, 0.88) | 0.9 | 0.82 | 4.65 (1.57, 9.78) | 0.435 |

| CBV <35% | 0.82 (0.77, 0.85) | 0.87 | 0.85 | 8.53 (–37.46, 53.35) | 0.706 |

| Alteplase patients | |||||

| CBF <25% | 0.81 (0.74, 0.89) | 0.86 | 0.79 | −9.50 (–26.95, 10.75) | 0.095 |

| CBF <30% | 0.83 (0.77, 0.85) | 0.84 | 0.77 | −1.52 (–11.89, 13.79) | 0.53 |

| CBF <35% | 0.79 (0.76, 0.83) | 0.81 | 0.76 | −1.18 (16.94, 18.05) | 0.844 |

| CBV <35% | 0.78 (0.66, 0.82) | 0.80 | 0.81 | −12.75 (–59.87, 24.52) | 0.272 |

| CBV <40% | 0.8 (0.76, 0.83) | 0.82 | 0.77 | 1.27 (–1.23, 4.9) | 0.019 |

| CBV <45% | 0.74 (0.69, 0.79) | 0.83 | 0.68 | 0.85 (–12.59, 9.12) | 0.435 |

CTP = computed tomography perfusion; DWI = diffusion‐weighted imaging; CBF = cerebral blood flow; CBV, cerebral blood volume; AUC = area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; IQR = interquartile range.

Figure 1.

Setting a more rigid CBF threshold of 20% allows for a more accurate ischemic core estimation in patients going to thrombectomy, whereas patients only receiving alteplase have greater core growth and so a threshold of CBF 30% is more appropriate. Here are 4 cases, 2 receiving thrombectomy (top two rows) and 2 receiving only alteplase (bottom two rows). We show the 24‐hour MRI DWI to display the 24‐hour infarct core (first column), and acute CTP core estimates at threshold of a CBF of 20% (second column) and a CBF of 30% (third column). In the thrombectomy patients, the CBF 20% more accurately predicts the 24‐hour DWI lesion volume and the CBF 30% estimate. However, in the alteplase patients, the CBF 30% is a more accurate representation of the resulting infarct volume in patients who show recanalization attributed to alteplase. CBF = cerebral blood flow; CTP = computed tomography perfusion; DWI = diffusion‐weighted imaging; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging. [Color figure can be viewed at www.annalsofneurology.org]

Figure 2.

Two Bland‐Altman plots comparing the differences in volumes presented with baseline core estimates using a CBF 30% threshold in (A) and a CBF 20% in (B). The volume of the CBF 30% (A) or 20% (B) core estimate are presented on the x‐axis divided by treatment type with patients in blue representing those who received rtPA and green representing those who had thrombectomy. The absolute volume difference between the baseline ischemic core volume at a CBF threshold and the 24‐hour core volume are presented on the y‐axis. The mean volume difference is represented by the green line and the 95% CIs are represented by the red lines. Applying a single perfusion threshold for both the thrombectomy and intravenous lytic treatment groups for infarct core prediction resulted in significant differences compared to setting separate thresholds for thrombectomy and for lytic‐treated patients. For alteplase‐treated patients, the CBF 30% threshold (B) was optimal and had a mean absolute difference between the baseline and 24‐hour core volume of −1.5ml (−11.8 to 13.39). However, for patients receiving thrombectomy, the CBF 30% ischemic core threshold significantly overestimated the resulting ischemic core volume. For thrombectomy‐treated patients, the CBF 20% threshold (A) was optimal and had a mean absolute difference between the baseline and 24‐hour core volume of 2.6ml (−4.3 to 8.7). CBF = cerebral blood flow; CI, confidence interval; rtPA = recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. [Color figure can be viewed at www.annalsofneurology.org]

Defining Ischemic Core in Patients Treated With Alteplase

In the alteplase‐treated patients, the optimal ischemic core threshold was rCBF <30% (AUC, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.77, 0.85). The next best threshold to define the ischemic core was CBV <40% (AUC, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.76, 0.83). An rCBF <20% and rCBV <30% to define the baseline core were less optimal because they underestimated the 24‐hour DWI infarct (AUC, 0.77; [CBV], <30%; AUC, 0.73). In contrast to the thrombectomy patients, the median volume difference between the rCBF <20% lesion and 24‐hour DWI lesion in alteplase‐treated patients was 14ml smaller (IQR, −31.54, −13.29ml; p = 0.041), whereas the rCBF <30% core volume was no different (median volume difference, 1.5ml; IQR, −11.89, 13.79; p = 0.53 between acute CBF 30% and 24‐hour DWI volume; Fig 2). The median absolute difference in thrombolysis patients between the 24‐hour DWI infarct core volume and the CBF <30% patients was −1.2ml (IQR, −3.4 to 1.2) whereas for a CBF <20 the median absolute difference was −7.8ml (IQR, −8.8 to −4.2).

Comparison Between Thrombectomy and Alteplase‐Only Groups

Despite being matched for occlusion location and clinical severity, thrombectomy patients had smaller 24‐hour DWI infarcts than the alteplase‐only patients (p = 0.011). Applying the same threshold (either rCBF 20% or rCBF 30%) to predict the ischemic core across combined thrombectomy and alteplase‐only patients was not optimal compared to applying separate thresholds (ie, rCBF 20% for thrombectomy patients and rCBF 30% for intravenous alteplase patients; Fig 2). Applying a single threshold at a CBF of 30% for all patients resulted in an AUC of 0.75, but when applying the optimal threshold to the two groups, the thrombectomy AUC of rCBF <20% was 0.89 (p < 0.001) and in alteplase‐only patients the AUC of rCBF <30% = 0.83 (p = 0.042).

Effect of Time to CTP and Time to Recanalization

Time from stroke onset to CTP did not have a significant interaction with the optimal threshold to predict the baseline ischemic core volume for the pooled endovascular and intravenous patient cohorts (p > 0.05). Within the endovascular cohort only, 54 (41%) patients achieved TICI 3 within 90 minutes and 78 (59%) after 90 minutes. In the thrombectomy patients with recanalization within 90 minutes, the optimal ischemic core threshold was rCBF <20% (AUC, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.79, 0.96), whereas in patients with recanalization beyond 90 minutes the optimal ischemic core threshold was rCBF <25% (AUC, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.76, 0.98). However, the 24‐hour DWI volume difference between time epochs did not reach statistical significance (median, 18.7ml <90 minutes group versus median, 15.8ml >90 minutes group; p = 0.273).

Discussion

This study has demonstrated that patients with early and confirmed complete revascularization following complete vessel occlusion have greater tissue salvage from areas of severe ischemia than those with delayed time of reperfusion. Using MIStar software, the optimal CTP threshold to estimate the baseline ischemic core in patients treated with thrombectomy was rCBF <20%, which is lower than the rCBF <30% threshold we observed (and has been previously reported) in patients treated with alteplase alone. The different thresholds for ischemic core in the two treatment groups are likely attributed to earlier and more complete tissue reperfusion, which is known to occur more commonly following thrombectomy than intravenous thrombolysis.13 This is also likely the reason that despite similar baseline CTP core and total perfusion lesion volumes, the thrombectomy group had smaller 24‐hour DWI infarct volumes and improved clinical outcomes. In our cohorts, CBF 20% core volume was not significantly different to 24‐hour DWI in thrombectomy patients, whereas the 30% core volume was larger as seen in Figures 1 and 2. The opposite was observed in intravenous thrombolysis patients, the 30% core volume being no different to 24‐hour DWI, with the 20% core volume being smaller with a median volume difference of 12ml.

These findings do not mean that ischemic core should be defined by treatment modality. For example, in the setting of rapid and complete reperfusion following intravenous thrombolysis, a patient may potentially have as much, or even more, tissue salvage as a thrombectomy patient who has TICI 3 reperfusion 90 minutes after imaging. Thus, we suggest using a stricter threshold to predict ischemic core in the setting of rapid and complete reperfusion (regardless of the reperfusion technique used). This notion is reinforced by the results, which indicate that a longer time to recanalization with endovascular therapy also resulted in a higher CBF threshold to determine the ischemic core volume, a finding also seen in a previous study19 (albeit without intravenous lysis patients). One option for the clinical translation of this data could be to provide CTP summary maps with a three‐color “traffic light” output for the ischemic core and penumbra. First, (1) a red‐coded region “stop” representing the CBF that is unlikely to be salvaged even with rapid reperfusion (with MIStar software this would be reported as a 0–20% threshold); (2) an orange‐coded region as a “speed up before it turns red” representing the tissue that may be lost if reperfusion is delayed (here reported as a 20–30% threshold); and (3) a green “go” penumbra (tissue with rCBF >30% but with DT >3 seconds). We suggest that an important clinical application is the situation where volumes differ between the upper and lower threshold core estimates. For example, if the rCBF 30% core estimate is above 100ml, acute reperfusion therapy might be considered futile by many. However, a much smaller rCBF 20% core estimate might prompt one to be more aggressive in offering acute reperfusion therapy in the hope that rapid reperfusion might salvage the tissue with rCBF between 20% and 30%. The same scenario might be assessed differently in a primary stroke center where the patient has to be transferred to an endovascular therapy capable center after intravenous thrombolysis. In that case, knowledge of the amount of brain tissue that might infarct in the time it takes to for the patient to be transported (and ultimately treated with thrombectomy) would play a crucial role in deciding whether transfer was appropriate.

There are important differences between our study and the prespecified analyses on subgroups of the SWIFT PRIME study,14 which showed no difference in the rCBF 30% core threshold by treatment modality, or in a separate analysis that did not show that a lower than rCBF 30% threshold for ischemic core was more predictive of follow‐up infarct volume.15 Although the SWIFT‐PRIME study was randomized by treatment modality, our patients were matched individually by age, baseline NIHSS, occlusion location, and perfusion lesion volume. We also included only patients with both >90% reperfusion and TICI 3 recanalization. Despite these more stringent recanalization/reperfusion criteria, this analysis had 264 patients with much larger baseline ischemic core volumes than the SWIFT PRIME analysis. Perhaps most important, this study used different postprocessing software to SWIFT PRIME, and it has been demonstrated that the optimal thresholds to define ischemia are specific to the software and postprocessing method utilized.12 Therefore, the CBF thresholds from our study may well be different when applied to other software. Nonetheless, we propose that the principle demonstrated in this analysis would apply to other software if tested on our data set. That is, tissue with a lower CBF can be salvaged from infarction with early complete reperfusion.

Study limitations need to be acknowledged. First, although INSPIRE is large and sites are strongly encouraged to enroll consecutive patients, the need for pretreatment multimodal CT and follow‐up MR, along with clinical data from several time points, means that, practically, not all treated patients were included. Second, in the alteplase‐treated patients, there was a median 19‐hour time difference between treatment and assessment of reperfusion. The reduced effectiveness of alteplase compared to thrombectomy may well have led to delayed reperfusion with some infarct growth between these time points in the alteplase group. However, the likely infarct growth in the interval between treatment and infarct measurement in the alteplase group reinforces the concept that ischemic core thresholds are likely to vary with time to reperfusion, and that further refinement of “reperfusion time‐dependent” thresholds may be required.16 Indeed, it possible that the CBF threshold for ischemic core may be even lower with even faster times to reperfusion and possibly with very short stroke onset to CTP times. However, we have no data on patients imaged and recanalized within 60 minutes of stroke onset on which to test this theory. Importantly, the threshold to predict infarction in the extended time window for patients undergoing thrombectomy also requires assessment. Last, this analysis was undertaken using an algorithm to minimize the effect of contrast delay and dispersion between the arterial input function (selected in an artery proximal to the occlusion) and the ischemic region. As such, the proposed CBF thresholds may not directly translate to algorithms used by other perfusion software.15, 17 Nonetheless, the underlying principles are the same, and we would expect that for patients who achieve rapid and complete reperfusion, a stricter rCBF threshold to estimate the volume of the ischemic core should be considered. However, the actual thresholds may differ.18

In conclusion, we have identified that the ischemic core in patients with complete known early reperfusion is better estimated by a lower CBF threshold. This suggests that more severely hypoperfused tissue can be salvaged by earlier and complete revascularization. It follows that the widely used CBF ischemic core thresholds developed in patients when timing of reperfusion is uncertain (eg, as commonly observed in intravenous lysis or untreated patients) may overestimate tissue truly destined to infarct in patients in whom early and complete reperfusion does occur. As such, we suggest caution if withholding reperfusion therapy from patients assessed with a single CBF threshold to estimate core volume. It may also be of interest to investigate whether reperfusion therapy with potentially more effective intravenous lytic agents such as tenecteplase19 result in similar salvage of what has typically been labeled as “core.”20

Author Contributions

A.B., T.K., F.M., K.B., and M.P. contributed to the conception and design of the study. A.B., L.L., C.L., and M.P. contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data. A.B., T.K., F.M., K.B., L.L., C.L., and M.P. contributed to drafting the text and preparing the figures.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

Nothing to report.

Supporting information

supporting information

Reference

- 1. Bivard A, Spratt N, Levi C, Parsons M. Perfusion computer tomography: imaging and clinical validation in acute ischaemic stroke. Brain 2011;134:3408–3416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Qiao Y, Zhu G, Patrie J, et al. Optimal perfusion computed tomographic thresholds for ischemic core and penumbra are not time dependent in the clinically relevant time window. Stroke 2014;45:1355–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Campbell BC, Christensen S, Levi CR, et al. Cerebral blood flow is the optimal CT perfusion parameter for assessing infarct core. Stroke 2011;42:3435–3440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lin L, Bivard A, Levi CR, Parsons MW. Whole‐brain CT perfusion is highly reliable in measuring acute ischemic penumbra and core. Radiology 2016;279:150319. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015150319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bivard A, McElduff P, Spratt N, Levi C, Parsons M. Defining the extent of irreversible brain ischemia using perfusion computed tomography. Cerebrovasc Dis 2011;31:238–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al; HERMES collaborators . Endovascular thrombectomy after large‐vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta‐analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet 2016;387:1723–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boned S, Padroni M, Rubiera M, et al. Admission CT perfusion may overestimate initial infarct core: the ghost infarct core concept. J Neurointerv Surg 2017;9:66–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, et al; EXTEND‐IA Investigators . Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion‐imaging selection. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1009–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, et al; SWIFT PRIME Investigators . Stent‐retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t‐PA vs. t‐PA alone in stroke. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2285–2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Parsons MW, Pepper EM, Bateman GA, et al. Identification of the penumbra and infarct core on hyperacute noncontrast and perfusion CT. Neurology 2007;68:730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bivard A, Stanwell P, Spratt N, et al. Defining acute ischemic stroke tissue pathophysiology with whole brain CT perfusion. J Neuroradiol 2014;41:307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bivard A, Levi C, Spratt N, Parsons M. Perfusion CT in acute stroke: a comprehensive analysis of infarct and penumbra. Radiology 2013;267:543–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Badhiwala JH, Nassiri F, Alhazzani W, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: a meta‐analysis. JAMA 2015;314:1832–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Albers GW, Goyal M, Jahan R, et al. Ischemic core and hypoperfusion volumes predict infarct size in SWIFT PRIME. Ann Neurol 2016;79:76–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mokin M, Levy EI, Saver JL, et al; SWIFT PRIME Investigators. Predictive Value of RAPID Assessed Perfusion Thresholds on Final Infarct Volume in SWIFT PRIME (Solitaire With the Intention for Thrombectomy as Primary Endovascular Treatment). Stroke 2017;48:932–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. d'Esterre CD, Boesen ME, Ahn SH, et al. Time‐dependent computed tomographic perfusion thresholds for patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2015;46:3390–3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cereda CW, Christensen S, Campbell BC, et al. A benchmarking tool to evaluate computer tomography perfusion infarct core predictions against a DWI standard. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016;36:1780–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Austein F, Riedel C, Kerby T, et al. Comparison of Perfusion CT Software to Predict the Final Infarct Volume After Thrombectomy. Stroke 2016;47:2311–2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Parsons M, Spratt N, Bivard A, et al. A Randomized Trial of Tenecteplase versus Alteplase for Acute Ischemic Stroke. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1099–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bivard A, Huang X, et al. The impact of CT perfusion imaging on the response to tenecteplase in ischemic stroke. Analysis of two randomized controlled trials. Circulation 2017;135:440–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

supporting information